Settler colonialism in Canada

Settler colonialism in Canada is the continuation and the results of the colonization of the assets of the Indigenous peoples in Canada. As colonization progressed, the Indigenous peoples were subject to policies of forced assimilation and cultural genocide. The policies signed many of which were designed to both allowed stable houses. Governments in Canada in many cases ignored or chose to deny the aboriginal title of the First Nations. The traditional governance of many of the First Nations was replaced with government-imposed structures. Many of the Indigenous cultural practices were banned. First Nation's people status and rights were less than that of settlers. The impact of colonization on Canada can be seen in its culture, history, politics, laws, and legislatures.

The current relationship of Indigenous peoples in Canada and the Crown is one that has been heavily defined by the effects of settler colonialism and Indigenous resistance.[1] Canadian Courts and recent governments have recognized and eliminated many discriminatory practices.

Government policies

Doctrine of Discovery

The Catholic Doctrine of Discovery is a legal doctrine that Louise Mandell asserted is a justification for settler colonialism in Canada.[2] The doctrine allowed Catholic European explorers to claim non-Christian lands for their monarch based on papal bulls.[3] The doctrine was applied to the Americas when Pope Alexander VI issued Inter caetera in 1493, giving Spain title to "discoveries" in the New World.[3] Spain, however, claimed only the Pacific coast of what is today Canada and, in 1789, established just the settlements of Santa Cruz de Nuca and Fort San Miguel,[4] both of which were abandoned six years later.

In the 2004 case Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed that "the doctrine of terra nullius never applied in Canada". Aboriginal title is a beneficial interest in land, although the Crown retains an underlying title.[5] The court set out a number of conditions which must be met in order for the Crown to extinguish Aboriginal title.[6] The court, 10 years later, in Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, rejected all Crown arguments for Aboriginal title extinguishment.[2]

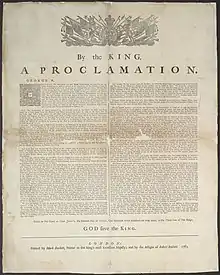

The Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763, issued by King George III, is considered one of the most important treaties in Canada between Europeans and Indigenous peoples, establishing the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Crown, which recognized Indigenous peoples rights, as well as defining the treaty making process, which is still used in Canada today.[7] The Royal Proclamation also acknowledged Indigenous peoples' constitutional right to sovereignty and self government. Within the document, both sides agreed that treaties were the most effective legal way for Indigenous peoples to release control of their land. However, the Royal Proclamation was drafted by the British government, without any Indigenous input, which resulted in a monopoly over the purchase of Indigenous lands by the Crown.[8] The Proclamation banned non-Indigenous settlers from claiming the land that was being populated by Indigenous peoples, unless the land had first been purchased by the Crown and then sold to the settlers.[9] As time passed, non-Indigenous settlers became eager to establish their own communities and extract resources to sell, forgoing the guidelines set out in the Proclamation.

On appeal of St Catharines Milling and Lumber Co v R in 1888, the imperial Privy Council found native land rights were derived from the Royal Proclamation of 1763.[10] In 1973, Calder v British Columbia (Attorney General), the Supreme Court of Canada found that the Indigenous peoples of Canada held an aboriginal title to their land, which was independent of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and was derived from the fact that, "when the settlers came, the Indians were there, organized in societies and occupying the land as their forefathers had done for centuries".[10]

Gradual Civilization Act of 1857

Assimilation was the goal for the Europeans for Indigenous individuals for much of history, this can be seen in the Gradual Civilization Act. This act was made in 1857 by CAct played on the idea of how Indigenous individuals were 'savages' that needed to be reformed by the 'civilized' Europeans, thus the act being called the Gradual Civilization Act. In some ways the Gradual Civilization Act was an extension of residential schools because it had the same goal but this Act was targeted towards Indigenous men instead of children. Thes Act made it so that Indigenous men, if they wanted to could become a part of the European-Canadian society, they were to give up many different aspects of their culture. The European-Canadian definition of being civilized entailed being able to speak and write in either English or French, and to be as similar to a white man as possible so that there were no discernible differences. There were commissioners that were tasked to make sure that these criteria were filled, and they examined Indigenous individuals to make sure that they were meeting the criteria. The outcome of this was that any individual that was deemed to meet the criteria could become enfranchised. The Act was a direct consequence of settler colonialism as the Indigenous individuals were forced to assimilate to the world views and customs of the settlers.[11]

The Indian Act of 1876

In 1876, the Indian Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada and allowed the administration of Indian Status, reserve lands, and local Indigenous governance.[12] The act gave the Canadian government control over Indigenous identity, political practices, governance, cultural practices, and education.[13] One of the underlying motivations in the act was to enforce a policy of assimilation, to prohibit Indigenous peoples from practicing their own cultural, political, and spiritual beliefs.[12][14] The act defined Indian Status and the entitlement and legal conditions that accompanied it, established land management regimes on reserves, managed the sales of natural resources, and defined band council powers and electoral systems.

Gender discrimination within the act enforced gender bias as another means of extinguishing Indian Status, thereby excluding women from their rights. Under this legislation, an Indian woman who married a non-Indian man would no longer be Indian. She would lose her status, treaty benefits, health benefits, the right to live on reserve, the right to inherit property, and even the right to be buried with ancestors. However, when an Indian man married a woman without status, he retained all his rights.

In 1951, the act was amended, to lift the various restrictions on Indigenous culture, religion, and politics. This included removing bans on potlatch and sun dance ceremonies. Additionally, these amendments allowed women to vote in band council elections and Elsie Marie Knott was the first woman to be elected chief in Canada. However, these actions didn't eliminate gender disparity in status requirements. Instead of having "Indian blood", status was assigned through the Indian Register, where male lines of descent were still privileged.[12] In 1985, the act was amended again, through Bill C-31, in order to reflect the newly enacted Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The amendment allowed women who "married out" of their band to apply for their rights and Indian status to be restored.[15]

Residential schools

The Canadian Indian residential school system was an extensive school system that was set up by the Government of Canada and organized and ran by Churches. Residential schools began operation in Canada in the 1880s and began to close during the end of the 20th century.[16] Residential school's main objectives were to educate Indigenous children, by teaching Euro-Canadian and Christian values and ways of living to assimilate Indigenous children into standard Canadian cultures. The values that were taught in residential schools were brought to Canada from the colonial settlers who made up a majority of the Canadian population at this time.

In Canada over 150,000 children attended residential schools throughout the century that they were in operation. The Indigenous children that attended residential schools were forcibly removed from their homes and families. While at residential schools, students were no longer allowed to speak their own language or acknowledge their culture or heritage without the threat of punishment.[17] If rules were broken the students were brutally punished. Residential schools were known for students experiencing physical, sexual, emotional and psychological abuse from the staff of the schools.[16] Residential schools resulted in generations of Indigenous peoples who lost their language and culture. The removal of homes at such a young age also resulted in generations of peoples who did not have the knowledge or skills to have families of their own.

As settlers began to populate Canada, they brought their own Eurocentric views that believed that their civilization was the ultimate goal. Settlers saw Indigenous people as savage pagans that needed to be civilized, with the best means of doing so was through government mandated education. Residential schools did not as much result in the education of Indigenous peoples, as much as it did result in a 'cultural genocide' of Indigenous peoples.[18] The establishment of residential schools is a direct link to colonial settlers and the values that they brought, when they began to populate what we know today as Canada.

Ongoing effects of colonialism in Canada

Colonialism in current times

Colonialism is defined by its practice of domination which includes the subjugation of one people, the colonizers over another, the colonized. The distinction of settler colonialism is its goal of replacing the people already living there. Through colonization Canada's Indigenous people have been subject to the destruction against their culture and traditions through assimilation and force. It can be argued that Colonialism and its effects are still ongoing when looking at current events.[19]

Forced sterilization of Indigenous people

Forced sterilization is defined as the removal of a person's reproductive organs either through force or coercion, and is viewed as a human rights violation.[20] Its effect against Indigenous women has also identified it as violence against women and a form of racial discrimination.[21] Canada has had a history of sterilization which has disproportionately affected Indigenous women in the North. This has led to proposals on how healthcare can be better tailored to address the discrimination Indigenous women face when receiving healthcare.[22]

Indigenous women have reported to having found out that their fallopian tubes had been tied without their consent or were coerced into agreeing to it by doctors who assured them it was reversible.[23] The interference in Indigenous peoples reproductive lives were justified using the ideology of Eugenics. Although the Sexual Sterilization Act in Canada was repealed in 1972, the sterilizations of Indigenous people have continued. While the policies of coercive sterilization on Indigenous women have been recognized as sexist, racist and imperialist the extent to which it has systematically impacted Indigenous women is not an isolated instance of abuse. It can be looked at as a part of a larger context involving the colonization and racism Indigenous people face.[24]

Missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls

Missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) is an ongoing issue that gained awareness through the efforts of the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) when it called for a national inquiry on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada.[25] A 2014 report by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, suggests that between 1980 and 2012 1,017 Indigenous women were victims of homicide with 164 Indigenous women still considered missing.[26] Statistics show that Indigenous women of at least 15 years of age are three times more likely than non-Indigenous women to be victims of a violent crime.[27] The homicide rates of Indigenous women between 1997 and 2000 were seven times higher than non-Indigenous women.[28]

.jpg.webp)

Janice Accose's book, Iskwewak--kah' ki yaw ni wahkomakanak, draws a connection between racist and sexist depictions of Indigenous women in popular literature and violence against Indigenous women, which Accose claims led to the issue of MMIWG.[29] Notable to MMIWG is the Highway of Tears, a 725-kilometre stretch of highway 16 in British Columbia, that has been the location of many murders and disappearances beginning in 1970, disproportionately of which have been Indigenous women.[30]

Mass incarceration

Mass incarceration is an ongoing issue between Indigenous peoples and Canada's legal system in which Indigenous people are overrepresented within the Canadian prison population. Mass incarceration of Indigenous peoples results from a variety of problems stemming from settler colonialism that Indigenous peoples face daily including, poverty, substance abuse, lack of education and lack of employment opportunities. In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada decided in R v Gladue that courts must consider the "circumstances of Aboriginal offenders."[31] This decision lead to the creation of Gladue reports which allow Indigenous people to go through pre-sentencing and bail hearings that consider the way colonialism has harmed the Indigenous offender including considering cultural oppression, abuse suffered in residential schools and poverty.[32] Thirteen years after the Gladue decision, the Supreme Court of Canada reaffirmed the decision in R v Ipeelee extending the decision to require courts to consider the impact of colonialism on every Indigenous person being sentenced.[32] These decisions were made to address the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the prison population, however, the population has only been steadily increasing. Indigenous peoples in Canada only make up about 5% of the total population yet, in 2020 Indigenous people surpassed 30% of people behind bars.[33] Further, in 2020 Indigenous women accounted for 42% of the female inmate population in Canada.[33] Compared to non-Indigenous people, Indigenous peoples are less likely to be released on parole, are disproportionately placed in maximum security facilities, are more likely to be involved in use of force or self-injury incidents, and are more often placed in segregation.[33]

Indigenous resistance

Indigenous mobilization against the 1969 White Paper

In 1969, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Minister of Indian Affairs Jean Chrétien proposed the White Paper, which recommended abolishing the Indian Act to extend full citizenship to Indigenous peoples after the Hawthorn report concluded Indigenous peoples were "citizens minus." If entered into force, Indigenous peoples would become an ethnic group 'equal' to others in Canada, therefore rendering Aboriginal title and rights 'unequal.' This policy espoused a liberal definition of equality in which legislated differences between Indigenous peoples and Canadians created inequities, rather than attributing inequities to the ongoing violence of settler colonialism. The White Paper indicated how colonial understandings of treaties as contracts differed from Indigenous understandings of covenants, as it would eliminate federal fiduciary responsibilities established by treaties and the Indian Act. Indigenous mobilization against the White Paper culminated in Harold Cardinal's Red Paper (also known as "Citizens Plus"). While the White Paper was not enacted, it was preceded and succeeded by further assimilation strategies.

Tk'emlupsemc, French-Canadian, and Ukrainian historian Sarah Nickel argued scholars marking the White Paper as a turning point in pan-Indigenous political mobilization obfuscates both local responses and longer histories of Indigenous struggles by unfairly centering one settler policy.[34] Further, Indigenous women's organizations were marginalized despite claims of pan-Indigenous mobilization against the White Paper.[34] This diminished the continuous presence of Indigenous women undertaking political struggles, especially on intersectional issues of Indigeneity and gender, such as marrying-out policies.[34]

Walking with Our Sisters

Another ongoing movement in direct relation to MMIWG is Walking with Our Sisters. It is a commemorative art installation using vamps, the tops of moccasins, as a way to represent the unfinished lives of the Indigenous women who are murdered or missing.

One such art installation is Every One by Cannupa Hanska Luger, an enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation who is of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Austrian, and Norwegian heritage.[35][36] This art installation, which was on display at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, is a massive piece made from ceramic beads that make up the face of an Indigenous woman. The goal of the installation is to raise awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women and to humanize Indigenous people.[37]

Wet'suwet'en resistance to pipeline projects

The Wetʼsuwetʼen First Nation, located in the northeast of British Columbia's central, interior region, has long been engaged in an ongoing dispute with the Canadian state over its rights and land. In the 1997 case, Delgamuukw v British Columbia, which expanded on the earlier Calder v British Columbia (AG) and helped codify the ideas that Aboriginal title existed prior to, and could exist outside of, Canadian sovereignty, the court determined that infringements against Aboriginal title by the Canadian state were possible. While several Indigenous groups negotiated terms of treaty with the Canadian Crown, the Wet’suwet’en reaffirmed their right to sovereignty and, in 2008, removed themselves from the treaty process with British Columbia altogether.[38]

See also

References

- "Timeline of Canadian Colonialism and Indigenous Resistance". The Leveller. 26 September 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Mandell, Louise (2017). "We Will Help Each Other Be Great and Good". In Ladner, Kiera L.; Tait, Myra J. (eds.). Surviving Canada: Indigenous Peoples Celebrate 150 Years of Betrayal. Winnipeg, Manitoba: ARP Books. pp. 414–435.

- Reid, Jennifer (2010). "The Doctrine of Discovery and Canadian Law". The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. 30: 335–359.

- John Eric Vining (2010). The Trans-Appalachian Wars, 1790-1818: Pathways to America's First Empire. Trafford Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4269-7964-4.

- Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia [2014] 2 SCR 257 at paragraphs 69–71

- Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia [2014] 2 SCR 257 at paragraph 77

- Canada, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs (19 September 2013). "Royal Proclamation of 1763: Relationships, Rights and Treaties – Poster". www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Coates, Colin; Peace, Thomas (Fall 2013). "The 1763 Royal Proclamation in Historical Context". Canada Watch. ISSN 1191-7733.

- Canada, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs (4 June 2013). "250th Anniversary of the Royal Proclamation of 1763". www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Watson, Blake A (2011). "The Impact of the American Doctrine of Discovery on Native Land Rights in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand". Seattle University Law Review. 34 (2): 532–535.

- Nîtôtemtik, Tansi (4 October 2018). "The Gradual Civilization Act". University of Alberta Law. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Joseph, Bob (2018). 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act. Port Coquitlam, BC: Indigenous Relations Press. pp. 24–72. ISBN 978-0-9952665-2-0.

- Hurley, Mary C. (23 November 2009). "The Indian Act". Library of Parliament.

- Wolfe, Patrick (2006). "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 143873621.

- Branch, Legislative Services (15 August 2019). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Indian Act". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (1 September 2020). "The Residential School System - History and culture". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Branch, Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications (3 November 2008). "Indian Residential Schools". www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Indian Residential Schools, Settler Colonialism and Their Narratives in Canadian History - Research - Royal Holloway, University of London". pure.royalholloway.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- "Colonialism Is Alive and Well in Canada". West Coast Environmental Law. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- "UN organizations call for an end to forced, coercive and involuntary sterilization". UN Women – Headquarters. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Indigenous women

- Browne, Annette J.; Fiske, Jo-Anne (1 March 2001). "First Nations Women's Encounters with Mainstream Health Care Services". Western Journal of Nursing Research. 23 (2): 126–147. doi:10.1177/019394590102300203. ISSN 0193-9459. PMID 11272853. S2CID 10978703.

- "The coerced sterilization of Indigenous women". New Internationalist. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Stote, Karen (2015). An act of genocide : colonialism and the sterilization of Aboriginal women. Black Point, Nova Scotia. ISBN 978-1-55266-732-3. OCLC 901996864.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action" (PDF). 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Government of Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (27 May 2014). "Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview | Royal Canadian Mounted Police". www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Violent victimization of Aboriginal women in the Canadian provinces, 2009". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "First Nations, Métis and Inuit Women". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Acoose, Janice (5 February 2016). Iskwewak kah' ki yaw ni wahkomakanak : neither Indian princesses nor easy squaws (2nd ed.). Toronto. ISBN 978-0-88961-576-2. OCLC 932093573.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Morton, Katherine A (30 September 2016). "Hitchhiking and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Billboards on the Highway of Tears". Canadian Journal of Sociology. 41 (3): 299–326. doi:10.29173/cjs28261. ISSN 1710-1123.

- Canada, Supreme Court of (1 January 2001). "Supreme Court of Canada - SCC Case Information - Search". scc-csc.lexum.com. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- Government of Canada, Department of Justice (5 August 2016). "3. Challenges and Criticisms in Applying s. 718.2(e) and the Gladue Decision - Spotlight on Gladue: Challenges, Experiences, and Possibilities in Canada's Criminal Justice System". www.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- Government of Canada, Office of the Correctional Investigator (16 April 2020). "Indigenous People in Federal Custody Surpasses 30% - Correctional Investigator Issues Statement and Challenge - Office of the Correctional Investigator". www.oci-bec.gc.ca. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- Nickel, Sarah (June 2019). "Reconsidering 1969: The White Paper and the Making of the Modern Indigenous Rights Movement". The Canadian Historical Review. University of Toronto Press. 100 (2): 223–238. doi:10.3138/chr.2018-0082-2. S2CID 182502690.

- "Creative Disruption Cannupa Hanska Luger builds sculptures and installations that shatter misconceptions". American Craft Council. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- "Denver Art Museum to present Each/Other: Marie Watt and Cannupa Hanska Luger". Resnicow. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Hanc, John (6 August 2020). "Illuminating the Plight of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- McCreary, Tyler; Turner, Jerome (2 September 2018). "The contested scales of indigenous and settler jurisdiction: Unist'ot'en struggles with Canadian pipeline governance". Studies in Political Economy. 99 (3): 223–245. doi:10.1080/07078552.2018.1536367. ISSN 0707-8552. S2CID 159161633.

Further reading

- Barker, Adam J. (2009). "The Contemporary Reality of Canadian Imperialism: Settler Colonialism and the Hybrid Colonial State". American Indian Quarterly. 33 (3): 325–351. doi:10.1353/aiq.0.0054. ISSN 0095-182X. JSTOR 40388468. S2CID 162692337.

- Barker, Adam J.; Rollo, Toby; Lowman, Emma Battell (2016). "Settler colonialism and the consolidation of Canada in the twentieth century". The Routledge Handbook of the History of Settler Colonialism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-54481-6.

- Barker, Adam J. (2015). "'A Direct Act of Resurgence, a Direct Act of Sovereignty': Reflections on Idle No More, Indigenous Activism, and Canadian Settler Colonialism". Globalizations. 12 (1): 43–65. doi:10.1080/14747731.2014.971531. S2CID 144167391.

- Bourgeois, Robyn (2018). "Race, Space, and Prostitution: The Making of Settler Colonial Canada". Canadian Journal of Women and the Law. 30 (3): 371–397. doi:10.3138/cjwl.30.3.002. S2CID 150210368.

- Coombes, Annie E. (2006). Rethinking Settler Colonialism: History and Memory in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7168-3.

- Denis, Jeffrey S. (2015). "Contact Theory in a Small-Town Settler-Colonial Context: The Reproduction of Laissez-Faire Racism in Indigenous-White Canadian Relations". American Sociological Review. 80 (1): 218–242. doi:10.1177/0003122414564998. S2CID 145609890.

- Freeman, Victoria (2010). ""Toronto Has No History!" Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada's Largest City". Urban History Review. 38 (2): 21–35. doi:10.7202/039672ar. hdl:1807/26356.

- Grimwood, Bryan S. R.; Muldoon, Meghan L.; Stevens, Zachary M. (2019). "Settler colonialism, Indigenous cultures, and the promotional landscape of tourism in Ontario, Canada's 'near North'". Journal of Heritage Tourism. 14 (3): 233–248. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527845. S2CID 150844100.

- Harris, Cole (2020). A Bounded Land: Reflections on Settler Colonialism in Canada. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-6444-2.

- Hoogeveen, Dawn (2015). "Sub-surface Property, Free-entry Mineral Staking and Settler Colonialism in Canada: Mineral Staking and Settler Colonialism in Canada". Antipode. 47 (1): 121–138. doi:10.1111/anti.12095.

- Paquette, Jonathan; Beauregard, Devin; Gunter, Christopher (2017). "Settler colonialism and cultural policy: the colonial foundations and refoundations of Canadian cultural policy". International Journal of Cultural Policy. 23 (3): 269–284. doi:10.1080/10286632.2015.1043294. S2CID 143347641.

- Preston, Jen (2017). "Racial extractivism and white settler colonialism: An examination of the Canadian Tar Sands mega-projects". Cultural Studies. 31 (2–3): 353–375. doi:10.1080/09502386.2017.1303432. S2CID 151583759.

- Preston, Jen (2013). "Neoliberal settler colonialism, Canada and the tar sands". Race & Class. 55 (2): 42–59. doi:10.1177/0306396813497877. S2CID 145726008.

- Simpson, Audra (2014). Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-7678-1.

- Wildcat, Matthew (2015). "Fearing social and cultural death: genocide and elimination in settler colonial Canada—an Indigenous perspective". Journal of Genocide Research. 17 (4): 391–409. doi:10.1080/14623528.2015.1096579. S2CID 146577340.

External links

- Aboriginal Peoples and Communities – Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- Aboriginal Heritage Resources and Services – Library and Archives Canada

- Battle for Aboriginal Treaty Rights – Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (Digital Archives)

- "Aboriginals: Treaties and Relations". Canada in the Making. Canadiana.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2004.

.svg.png.webp)