Sixth Party System

The Sixth Party System is the era in United States politics following the Fifth Party System. As with any periodization, opinions differ on when the Sixth Party System may have begun, with suggested dates ranging from the late 1960s to the Republican Revolution of 1994. Nonetheless, there is agreement among scholars that the Sixth Party System features strong division between the Democratic and Republican parties, which are rooted in socioeconomic class, cultural, religious, educational and racial issues, and debates over the proper role of government.[1]

.svg.png.webp) | ||

| ||

|

| ||

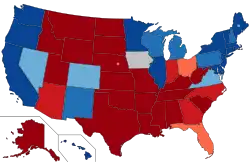

United States presidential election results between 1980 and 2020. Blue shaded states usually voted for the Democratic Party, while red shaded states usually voted for the Republican Party. | ||

Scholarly perspectives

The Sixth Party System is characterized by an electoral shift from the electoral coalitions of the Fifth Party System during the New Deal. The Republican Party became the dominant party in the South, rural areas, and suburbs, and its voter base became shaped by White Evangelicals.[2] Meanwhile the Democratic Party became the dominant party in urban areas, and its voter base diversified to include trade unionists, urban machinists, progressive intellectuals, as well as racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. A critical factor was the major transformation of the political system in the Reagan Era of the 1980s and beyond.[3][4]

No clear disciplinary consensus has emerged pinpointing an electoral event responsible for shifting presidential and congressional control since the Great Depression of the 1930s, when the Fifth Party System emerged. Much of the work published on the subject has come from political scientists explaining the events of their time either as the imminent breakup of the Fifth Party System, and the installation of a new one, or in terms of such transition taking place some time ago. In 2006, Arthur Paulson argued that a decisive realignment took place in the late 1960s. Other current writing on the Fifth Party System expresses admiration of its longevity, as the first four systems lasted about 30 to 40 years each, which would have implied that the early 21st century should see a Seventh Party System.[5] Previous party systems ended with the dominant party losing two consecutive House elections by large margins, and also losing a presidential election coinciding with or immediately following the second House election, which are decisive electoral evidence of political realignment, as it happened in the 1896 election. Such a shift took place between 2006 and 2008 in favor of the Democrats, but the Republicans won the elections of 2010 by their biggest landslide since 1946 and finished the 2014 elections with their greatest number of House seats since 1928.[6]

According to the 2017 edition of The Logic of American Politics, "a sixth party system is now in place." Although the precise starting date is a matter of debate, "the most salient difference between the current and New Deal party systems is the Republican Party's increased strength, exemplified by 20 majorities in the house and senate in six straight elections (1994–2004), unprecedented since the fourth party system, [its] retaking of the House in 2010 and the Senate in 2014 [...] and its sweeping national victory in 2016."[7]

Writing in 2020, political scientists Mark D. Brewer and L. Sandy Maisel argue "[i]t seems safe to state that the sixth American party system featured strong divisions between Republicans and Democrats, rooted in cleavages based on social class, social and cultural issues, race and ethnicity, and the proper size and scope of the federal government."[1] In Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process (2021), Brewer and Maisel argue that the consensus among experts is that the Sixth System is underway based on American electoral politics since the 1960s, stating: "Although most in the field now believe we are in a sixth party system, there is a fair amount of disagreement about how exactly we arrived at this new system and about its particular contours. Scholars do, however, agree that there has been significant change in American electoral politics since the 1960s."[1]

Dating

Opinions on when the Sixth Party System began include the elections of 1966 to 1968, the election of 1972, the 1980s when both parties began to become more unified and partisan, and the 1990s due to cultural divisions.[8][9][10][11]

Political scientist Stephen C. Craig argues for the 1972 election, when Richard Nixon won a 49-state landslide. He notes that "[t]here seems to be consensus on the appropriate name for the sixth party system. [...] Changes that occurred during the 1960s were so great and so pervasive that they cry out to be called a critical-election period. The new system of candidate-centered parties is so distinct and so portentous that one can no longer deny its existence or its character."[11]

The Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History dates the start in 1980, with the election of Reagan and a Republican Senate.[12] Arthur Paulson argues that "[w]hether electoral change since the 1960s is called 'realignment' or not, the 'sixth party system' emerged between 1964 and 1972."[13]

Seventh Party System

Since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, the Republican Party's more moderate, neoconservative faction has been increasingly ostracized by a growing far-right, paleoconservative faction, most commonly known as Trumpists. Peter J. Katzenstein, Professor of International Studies at Cornell University, believes that Trumpism rests on three pillars, namely nationalism, religion, and race.[14] According to Jeff Goodwin, Trumpism is characterized by five key elements: social conservatism, capitalism, economic nationalism, nativism, and White nationalism.[15]

The conflict between Trumpists and members of the Never Trump movement can perhaps most prominently be exemplified by the significant difficulty experienced by Kevin McCarthy in being elected Speaker of the House of Representatives in 2023, as many members of the far-right House Freedom Caucus refused to vote for him. This was highly unusual, as the Speaker of the House is typically elected on the first ballot, rather than on the fifteenth as McCarthy was.[16][17] McCarthy's tensions with the Freedom Caucus continued throughout his tenure, culminating in the caucus voting to oust him from his position in October; McCarthy is the first Speaker of the House to be removed by the House of Representatives.[18][19][20]

Moderate Republicans such as Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger also faced serious opposition, including censure, from many fellow Republicans due to their condemnation of Donald Trump following the January 6 United States Capitol attack, and participation in the bipartisan House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack.[21] This backlash would soon cause Liz Cheney to lose her seat representing Wyoming's at-large congressional district to Trump-endorsed Republican primary candidate Harriet Hageman,[22] after having been ousted as Chair of the House Republican Conference the previous year to be succeeded by Trump-endorsed Representative Elise Stefanik.[23]

Mark D. Brewer and L. Sandy Maisel speculate that "in the wake of Donald Trump's 2016 presidential victory, there is now strengthening debate as to whether we are entering a new party system as Trump fundamentally reshapes the Republican party and the Democratic party responds and evolves as well."[24] Some also argue that the supposed Seventh Party System began in 2008, as the election of the first Black President inflamed the American far-right to an unprecedented degree, with this arguably becoming a significant contributing factor to Donald Trump's victory in 2016.[25]

Some scholars and pundits have also posited that the Sixth Party System has ended while the Seventh Party System has not yet begun, and that the current system is merely a unique transition phase between the two. Another noteworthy feature of the Sixth/Seventh Party System is that Republicans have lost the popular vote in seven out of the last eight presidential elections, with their only victory being with the re-election of George W. Bush in 2004.[26]

Possible dealignment period

One possible explanation for the lack of an agreed-upon beginning of the Sixth Party System is that there was a brief period of dealignment immediately preceding it. Dealignment is a trend or process whereby a large portion of the electorate abandons its previous partisan affiliation without developing a new one to replace it. Ronald Inglehart and Avram Hochstein identify the time period of the American dealignment as 1958 to 1968.[27] Although the dealignment interpretation remains the consensus view among scholars, a few political scientists argue that partisanship remained so powerful that dealignment was much exaggerated.[28]

Issues

Harris and Tichenor argue: "At the level of issues, the sixth party system was characterized by clashes over what rights to extend to various groups in society. The initial manifestations of these clashes were race-based school desegregation and affirmative action, but women's issues, especially abortion rights, soon gained equal billing. [...] To these were added in the 1980s environmental defense and in the 1990s gay rights."[29]

New voter coalitions included the emergence of the "religious right", which is a combination of Catholics and Evangelical Protestants united on opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage. Southern white voters started voting for Republican presidential candidates in the 1950s, and Republican state and local candidates in the 1990s.[30]

Nominating candidates

In the chaotic campaign for the Democratic nomination in 1968, Hubert Humphrey won the nomination without entering any primaries. He was selected by state and local party officials. The old system of using county caucuses and state party conventions to pick the delegates largely gave way in 1972 to primaries, thanks to the reforms proposed by the McGovern–Fraser Commission for the Democrats. The Republicans followed suit.[31] One result was that locally powerful politicians lost their power to shape national tickets, and their influence in Washington. The new-style national convention was rarely the site of bargaining and dealing, but instead became a ratification ceremony run by the winner in the primaries.[32]

Campaign finance

Even more dramatic was the increase in spending thanks to new fund-raising techniques. The major growth was not in the business or labor sectors, but in the network organizations of political parties, and most particularly the national organizations of state elected and party officials.[33] The U.S. Supreme Court gave decisive support to reducing limits in Citizens United v. FEC (2010). That decision enabled corporations, labor unions, and Super PACs, among others, to advertise as much as they please within 30 days of a primary election or within 60 days of a general election. Two years before the decision, the 2008 presidential election saw spending independent of the parties of $144 million. In the 2012 presidential election, independent spending had soared to over $1 billion.[34] At the state level, the 21st century saw a new electoral arena, with heavy fundraising and spending on advertising in campaigns for justices of state supreme courts.[35] In 2016 and 2020, Bernie Sanders financed presidential campaigns heavily from small-dollar donations generated online.[36]

Since 1980, the only three presidential elections which have been won by the campaign that raised less money have been the campaigns for Ronald Reagan, which in 1980 raised less money than Jimmy Carter's campaign; Bill Clinton, which in 1996 raised less money than Bob Dole's campaign; and Donald Trump, which in 2016 raised less money than Hillary Clinton's campaign.[37][38]

See also

References

- Mark D. Brewer and L. Sandy Maisel, Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process (9th ed. 2021) p 42 online

- "The basic story of evangelical Christians’ transformation from a group that was relatively quiescent in the political arena into one that would become a major part of the Republican Party’s coalition has been told numerous times," according to Jacob R. Neiheisel, "Moral Victories in the Battle for Congress: Cultural Conservatism and the House GOP" Political Science Quarterly, 136#2 (2021) pp. 379–380, https://doi.org/10.1002/polq.13191

- Sean Wilentz, The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008 (2008)

- Robert M. Collins (2009). Transforming America: Politics and Culture During the Reagan Years. Columbia UP. p. 57. ISBN 9780231124010.

[The Reagan presidency] produced a political transformation that altered substantially the terms of debate in American politics and public life.

- Aldrich (1999).

- Sean Sullivan. "McSally win gives GOP historic majority in House". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

- Samuel Kernell; Gary C. Jacobson; Thad Kousser; Lynn Vavreck (2017). The Logic of American Politics, 8th edition. SAGE Publications. p. 21. ISBN 9781506358635.

- "What is the sixth party system". 19 May 2011.

- "The Sixth Party System in American Politics (1976-2012)". talkelections.org.

- Alex Copulsky (July 24, 2013). "Perpetual Crisis and the Sixth Party System".

- Stephen C. Craig, Broken Contract? Changing Relationships between Americans and Their Government (1996) p. 105

- Michael Kazin, et al. eds, The Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History (2009) Vol. 2, pg. 288

- Arthur Paulson, "Party change and the shifting dynamics in presidential nominations: The Lessons of 2008." Polity 41.3 (2009): 312-330, quoting page 314.

- Katzenstein, "Trumpism is US" WZB (March 20, 2019) online

- Gregory Krieg and Dan Merica, " Trumpism without Trump: Democrats confront a defeated President's growing movement" CNN November 9, 2020 online

- Matza, Max (January 5, 2023). "Three days. Eleven votes. Still no US House speaker". BBC News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- Zurcher, Anthony (January 7, 2023). "What has Kevin McCarthy given up, and at what price?". BBC News. Archived from the original on January 7, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- Hughes, Shiobhan; Katy S., Ferek; Kristina, Peterson (October 3, 2023). "Kevin McCarthy Ousted as House Speaker in Historic Vote". The Wall Street Journal.

- Wilkie, Emma Kinery,Christina (October 3, 2023). "House ousts Kevin McCarthy as speaker, a first in U.S. history". CNBC. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wise, Alana (February 4, 2022). "RNC votes to censure Reps. Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger over work with Jan. 6 panel". NPR. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Allen, Jonathan (August 16, 2022). "Rep. Liz Cheney loses her primary in Wyoming to Trump-backed challenger". NBC News. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Solender, Andrew (May 12, 2021). "Liz Cheney Ousted As GOP Conference Chair In Overwhelming Voice Vote". Forbes. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Brewer and Maisel, Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process (9th ed. 2021) p 42 online

- Reid, Joy-Ann (October 20, 2017). "The Seeds of Trump's Victory Were Sown the Moment Obama Won". THINK. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Stellino, Molly. “Fact Check: Last Republican to Win Popular Vote Left Office 14 Years Ago, Not 30.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 9 Feb. 2023, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2023/02/09/fact-check-false-claim-electoral-college-republicans-misleads/11214140002/.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Avram Hochstein. "Alignment and Dealignment of the Electorate in France and the United States." Comparative Political Studies 5.3 (1972): 343-372.

- Russell J. Dalton (2013). The Apartisan American: Dealignment and Changing Electoral Politics. CQ Press. p. 1. ISBN 9781452216942.

- Richard A. Harris; Daniel J. Tichenor (2009). A History of the U.S. Political System: Ideas, Interests, and Institutions. ABC-CLIO. p. 98. ISBN 9781851097180.

- J. David Woodard, The New Southern Politics (2006). For a graph of the movement of Southern white voters see Brian F. Schaffner (2010). Politics, Parties, and Elections in America (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 31. ISBN 9780495899167.

- Jeffrey S. Walz and John Comer, "State Responses to National Democratic Party Reform," Political Research Quarterly 52.1 (1999): 189-208.

- David B. Truman, "Party reform, party atrophy, and constitutional change: Some reflections." Political Science Quarterly 99.4 (1984): 637-655 online

- Keith E. Hamm, et al., "Independent spending in state elections, 2006–2010: vertically networked political parties were the real story, not business." The Forum 12#2 (2014) online

- Wendy L. Hansen, et al. "The effects of Citizens United on corporate spending in the 2012 presidential election." Journal of Politics 77.2 (2015): 535-545. online

- Chris W. Bonneau, "Patterns of campaign spending and electoral competition in state supreme court elections." Justice System Journal 25.1 (2004): 21-38.

- Anthony Corrado and Molly Corbett, “Rewriting the Playbook on Presidential Campaign Financing,” in Campaigning for President, 2008, edited by Dennis W. Johnson (Routledge, 2009) pp. 126–46

- "The Most Expensive Election Ever". Brennan Center for Justice.

- Krumholz, Sheila (August 23, 2012). "Will money buy the White House?". CNN.

Further reading

- Aberbach, Joel D., and Gillian Peele, eds. Crisis of Conservatism?: The Republican Party, the Conservative Movement, and American Politics After Bush (2011) excerpt and text search

- Aldrich, John H. (1999). "Political Parties in a Critical Era". American Politics Research. 27 (1): 9–32. doi:10.1177/1532673X99027001003. S2CID 154209484. speculates on emergence of Seventh Party System

- Alterman, Eric, and Kevin Mattson. The Cause: The Fight for American Liberalism from Franklin Roosevelt to Barack Obama (2012) biographical approach by liberal experts; excerpt and text search

- Bibby, John F. "Party Organizations, 1946–1996," in Byron E. Shafer, ed. Partisan Approaches to Postwar American Politics (1998)

- Brands, H.W. The Strange Death of American Liberalism (2003); a liberal view

- Brewer, Mark D., and L. Sandy Maisel. Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process (9th ed. 2021) pp 42–47 excerpt.

- Collins, Robert M. Transforming America: Politics and Culture During the Reagan Years, (2007).

- Critchlow, Donald T. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the Republican Right Rose to Power in Modern America (2nd ed. 2011); a conservative view

- Ehrman, John. The Eighties: America in the Age of Reagan (2008); a conservative view

- Hayward, Steven F. The Age of Reagan: The Fall of the Old Liberal Order: 1964–1980 (2009), a conservative interpretation

- Hayward, Steven F. The Age of Reagan: The Conservative Counterrevolution 1980–1989 (2009) excerpt and text search

- Jensen, Richard. "The Last Party System: Decay of Consensus, 1932–1980," in The Evolution of American Electoral Systems (Paul Kleppner et al. eds.) (1981) pp. 219–25,

- Kabaservice, Geoffrey. Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, From Eisenhower to the Tea Party (2012) scholarly history favorable to moderates excerpt and text search

- Kazin, Michael. What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party (2022)excerpt

- Martin, William. With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America, (1996)

- Niemi, Richard G., and John H. Aldrich. "The sixth American party system: Electoral change, 1952–1992." in Broken Contract? (Routledge, 2018) pp. 87-109.

- Paulson, Arthur. Electoral Realignment and the Outlook for American Democracy (2006)

- Rauch, Jonathan; La Raja, Raymond J. (December 7, 2017). "Re-engineering politicians: How activist groups choose our candidates—long before we vote". The Brookings Institution.

- Schlesinger, Arthur, Jr., ed. History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2008 (2011) 3 vol and 11 vol editions; detailed analysis of each election, with primary documents; online v. 1. 1789-1824 -- v. 2. 1824-1844 -- v. 3. 1848-1868 -- v. 4. 1872-1888 -- v. 5. 1892-1908 -- v. 6. 1912-1924 -- v. 7. 1928-1940 -- v. 8. 1944-1956 -- v. 9. 1960-1968 -- v. 10. 1972-1984 -- v. 11. 1988-2001

- Shade, William G., and Ballard C. Campbell, eds. American presidential campaigns and elections (Routledge, 2020) .

- Shafer, Byron E. "Where Are We in History? Political Orders and Political Eras in the Postwar U.S.," The Forum (2007) Vol. 5#3, Article 4. online edition

- Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History 1974–2008 (2008), by a leading liberal.

- Zernike, Kate. Boiling Mad: Inside Tea Party America (2010), by a New York Times reporter