Sapeornis

Sapeornis is a monotypic genus of avialan which lived during the early Cretaceous period (late Barremian to early Aptian, roughly 125-120 mya). Sapeornis contains only one species, Sapeornis chaoyangensis.

| Sapeornis Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil specimen, National Museum of Natural Science | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avialae |

| Clade: | Avebrevicauda |

| Family: | †Omnivoropterygidae |

| Genus: | †Sapeornis Zhou & Zhang, 2002 |

| Species: | †S. chaoyangensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Sapeornis chaoyangensis Zhou & Zhang, 2002 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

Description

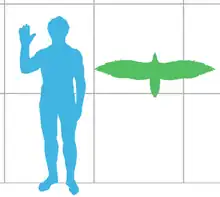

Sapeornis was large for an early avialan, about 30–33 centimetres (0.98–1.08 ft) long in life, excluding the tail feathers.

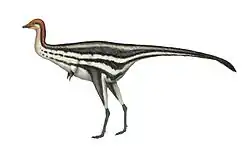

The hand of Sapeornis was far more derived than that of Archaeopteryx. It had three fingers, the outer ones with two and the middle one with three phalanges, and a well-fused carpometacarpus. Its arms were about half again as long as the legs, suggesting a large wing area. On the other hand, its shoulder girdle was apparently ill-adapted to flapping flight and its furcula was unusual, with a hypocleidum similar to more advanced avialans but a general anatomy even more basal than in Archaeopteryx.[2] The humerus was large and bore holes, apparently to save weight, as in the Confuciusornithidae.

The skull has a handful of teeth in the upper jawtip only. Sapeornis had gastralia but no (or unossified) uncinate processes. The breastbone (sternum) was either absent or, more likely, made of cartilage rather than bone, as in more basal theropods.[3] The pygostyle was rod-like as in Confuciusornis and Nomingia, but like in the former there was no long bony tail anymore. While the tarsometatarsi were more fused than in Archaeopteryx, the fibula was long and reached the distal point of the tarsal joint, not reduced as in more modern birds (and some non-avian theropods like Avimimus). The first toe pointed backwards. In specimen IVPP V12375, the stomach contained numerous small gastroliths. Analysis of its skeletal bones suggest that it had an ontogeny and slow growth like Archaeopteryx and small carnivorous dinosaurs, rather than the explosively fast growth seen in modern birds.[4]

In absolute number of features shared with modern birds, S. chaoyangensis is about as derived as Confuciusornis. However, the apomorphies were largely different from Confuciusornis, and a character analysis demonstrates that these two were not closely related.[5] The tail plumage of Sapeornis consisted of rectrices that formed a graded, fan-like structure. The reduced fingers suggest that it might have had an alula. Not being well-adapted to flapping flight, Sapeornis probably was a glider and/or soarer that preferred more open country compared to the Enantiornithes and predominantly woodland birds, although it was able to perch on branches. The small gastroliths, overall large size, and the inferred habitat indicate that Sapeornis was most likely a herbivore, possibly eating plant seeds and fruits.[6]

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Sapeornis and modern birds and reptiles indicate that it may have been diurnal, similar to most modern birds.[7]

Discovery and history

Sapeornis is known from fossils found in Jiufotang Formation and Yixian Formation rocks in western Liaoning, China. These rocks formed during the late Aptian through early Albian epochs of the Cretaceous period, and are about 125-120 million years old. Several nearly complete skeletons have been found.[6]

The first known specimen (the type specimen) of Sapeornis was an incomplete skeleton dug up from Jiufotang Formation rocks in the area of Shangheshou, near Chaoyang City in Liaoning Province, China in the summer of 2000. It was discovered by a team from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), and was reported in 2002 by the scientists Zhonghe Zhou and Fucheng Zhang.[8] They chose the name in honor of SAPE, the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, which they combined with the Ancient Greek word όρνις (ornis), meaning "bird". The species name chaoyangensis is Latin for "from Chaoyang".[9] Soon after this, two more, nearly complete specimens were discovered in the Dapingfang area, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) from the original fossil site. None of these first three specimens preserved traces of feathers, but based on the size of their skeletons alone, they were recognized as the largest early Cretaceous avialans known at the time.[9]

In 2008, Yuan named a new specimen related to Sapeornis as Didactylornis jii. Yuan concluded that Didactylornis differed from Sapeornis in the proportions of the foot and number of wing and foot bones.[10] However, the relevant portions of the specimen were badly crushed, and later authors concluded that these differences were based on misinterpretation of the poorly preserved specimen. In a 2010 survey of Chinese avialan fossils, Li and colleagues considered Didactylornis a synonym of Sapeornis chaoyangensis.[11] In a 2012 study, Gao et al. concluded that Didactylornis was indeed a junior synonym of Sapeornis chaoyangensis, as were Shenshiornis and the supposed second species of Sapeornis, S. angustis.[12] Omnivoropteryx is also likely synonymous with Sapeornis.[13]

References

- Hu, D.; et al. (2010). "A new sapeornithid bird from China and its implication for early avian evolution". Acta Geologica Sinica. 84 (3): 472–482. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2010.00188.x. S2CID 86441777.

- Senter, Phil (2006). "Scapular orientation in theropods and basal birds, and the origin of flapping flight" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (2): 305–313.

- Foth, C. (2014). Comment on the absence of ossified sternal elements in basal paravian dinosaurs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(50): E5334-E5334. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419023111

- Erickson, Gregory M.; Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Zhou, Zhonghe; Turner, Alan H.; Inouye, Brian D.; Hu, Dongyu; Norell, Mark A. (2009). "Was Dinosaurian Physiology Inherited by Birds? Reconciling Slow Growth in Archaeopteryx". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7390. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007390. PMC 2756958. PMID 19816582.

- Zhou, Zhonghe; Zhang, Fucheng (2006). "A beaked basal ornithurine bird (Aves, Ornithurae) from the Lower Cretaceous of China". Zool. Scripta. 35 (4): 363–373. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2006.00234.x. S2CID 85222311.

- Zhou, Zhonghe & Zhang, Fucheng (2003): Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40(5): 731–747. doi:10.1139/E03-011 (HTML abstract)

- Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407.

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. (2002). "Largest Bird from the Early Cretaceous and Its Implications for the Earliest Avian Ecological Diversification". Naturwissenschaften. 89 (1): 34–38. doi:10.1007/s00114-001-0276-9. PMID 12008971. S2CID 1116829.

- Zhou, Z., & Zhang, F. (2003). Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 40(5): 731-747. doi:10.1139/E03-011

- Yuan, C. (2008). "A new genus and species of Sapeornithidae from Lower Cretaceous in western Liaoning, China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 82 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2008.tb00323.x. S2CID 86691693.

- Li, D.; Sullivan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z. (2010). "Basal birds from China: a brief review". Chinese Birds. 1 (2): 83–96. doi:10.5122/cbirds.2010.0002. S2CID 84976296.

- Gao, C.; Chiappe, L.M.; Zhang, F.; Pomeroy, D.L.; Shen, C.; Chinsamy, A.; Walsh, M.O. (2012). "A subadult specimen of the Early Cretaceous bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis and a taxonomic reassessment of sapeornithids". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (5): 1103–1112. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.693865. S2CID 86195304.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)