Sidetic language

The Sidetic language is a member of the extinct Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family known from legends of coins dating to the period of approximately the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE found in Side at the Pamphylian coast, and two Greek–Sidetic bilingual inscriptions from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE respectively. The Greek historian Arrian in his Anabasis Alexandri (mid-2nd century CE) mentions the existence of a peculiar indigenous language in the city of Side. Sidetic was probably closely related to Lydian, Carian and Lycian.

| Sidetic | |

|---|---|

| Region | Ancient southwestern Anatolia |

| Extinct | after the third century BCE |

Early forms | |

| Sidetic script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xsd |

xsd | |

| Glottolog | side1240 |

The Sidetic script is an alphabet of the Anatolian group. It has about 25 letters, only a few of which are clearly derived from Greek. Consensus is growing that the script has essentially been deciphered.[1]

Evidence

Inscriptions and coins

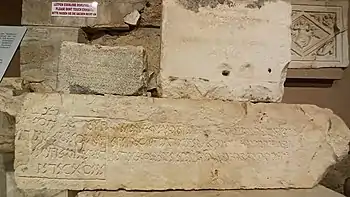

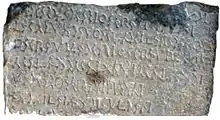

Coins from Side were first discovered in the 19th century, which bore legends in a then-unknown script. In 1914, an altar came to light in Side with a Greek inscription and a Sidetic one, but the latter could not be deciphered. It was only after the discovery of a second Greek-Sidetic bilingual inscription in 1949, that Hellmut Theodor Bossert was able to identify 14 letters of the Sidetic script using the two bilinguals.[2] In 1964 a large stone block was unearthed near the east gate of Side, with two longer Sidetic texts, including loan words from Greek (istratag from στρατηγός, 'commander' and anathema- from ἀνάθημα, 'votive offering'). In 1972, a text was found outside Side for the first time, at the neighbouring town of Lyrbe-Seleukia. Currently, eleven Sidetic coins and several coins with Sidetic legends are known.

Citations

In addition to the inscriptions, two Sidetic words are known from ancient Greek texts: ζειγάρη for cicada,[3] mentioned by the ancient lexicographer Hesychius, and λαέρκινον for Valeriana, cited by Galen. In addition, it is believed that some incomprehensible characters in the third book of Hippocrates' Epidemics were originally quotations of the doctor Mnemon of Side, which might have been in the Sidetic script.[4]

Catalogue of Sidetic texts

The designated number and date of discovery are given:

- S1 = S I.1.1 Artemon bilingual from Side (1914).

- S2 = S I.1.2 Apollonios bilingual from Side (1949).

- S3 & S4 = S I.2.1-2 Strategos dedications from Side (1964).

- S5 = S II.1.1 Palimpsest bronze altar table or voting tablet (1969).

- S6 = S I.1.3 Euempolos bilingual from Lyrbe-Seleukia (1972).

- S7 = S I.2.3 Inscription on fragment of the rim of a pot (1982).

- S8 = S I.2.4 Inscription on stone Heraldes relief (1982).

- S9 = S I.2.5 A list of names,[5] also interpreted as the "Athenodoros memorial"[6] - at six complete lines (and traces of two more lines), this is the longest Sidetic inscription (1995).

- S10 = S III 5th century BC coins with around twenty different legends (since 19th century).

- S11 Words possibly from Mnemon,[7] a physician of Side (1983), who added notes in Sidetic to a Greek Hippocrates manuscript.[8]

- S12 = S II.2.1 A steatite scarab, of uncertain provenance ("acquired in Turkey"); on its underside three (?) hardly identifiable signs have been carved, possibly Sidetic (2005).[9]

- S13 = S I.2.6 Graffito from Lyrbe-Seleukia (2014).

In addition a few Sidetic words have been handed down via classical authors, though not written in Sidetic script: "laerkinon" (λαέρκινον, = the herb valerian), "zeigarê" (ζειγάρη, a cricket, cicada).[10]

Characteristics of Sidetic

The Sidetic script

| Sidetic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | alphabet

|

| Direction | Right to left |

| Languages | Sidetic |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Sidt (180), Sidetic |

Texts in the Sidetic language are written right to left in an alphabet of about 25 characters. Since the 2010s consensus has grown with regard to the transliteration of the characters:

| sign | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (variants:) | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||||||||||

| transliteration | a | e | i | o | u | v | j | p | τ | m | t | d | θ | z | s | n | l | š | g | χ | r | k | ñ | c | δ | (?) |

| (superseded transliterations:) | (w, j) | (w) | (ç, φ) | (ś) | (ṯ) | (b) | (ñ) | (z) | (signs attested on coins only) | |||||||||||||||||

| IPA sound | /a/, /æ/? | /e/ | /i/ | /o/ | /u/ (/w/?) | /w/? | /j/? | /p/ | /ts/? | /m/ | /t/ | /d/ | /tʰ/ | /z/, /s/? | /s/ | /n/ | /l/ | /ʃ/ or /tʃ/ | /g/ | /kʰ/ | /r/ | /k/ | /ɲ/? | /dʒ/? | /dz/? |

The meaning of two-thirds of the characters is now firmly established, but there are still severe uncertainties: for example, while the majority view is that the frequent vertical strokes (![]() or

or ![]() ) are a character denoting a sibilant (z or s), that as a genitival ending would fit in nicely with the usual paradigms of the Anatolian languages,[5] others interpret the strokes as word dividers.[6]

) are a character denoting a sibilant (z or s), that as a genitival ending would fit in nicely with the usual paradigms of the Anatolian languages,[5] others interpret the strokes as word dividers.[6]

The Sidetic language

The inscriptions show that Sidetic was already strongly influenced by Greek at the time when they were created. Like Lycian and Carian, it was part of the Luwian language family. However, only a few words can be derived from Luwian roots, like maśara 'for the gods' (Luwian masan(i)-, 'god', 'divinity'), and, possibly, malwadas 'votive offering' (Luwian malwa-; but alternative readings are possible, for example, Malya das, 'he dedicated to Malya [= Athena]'). It has been argued that there were also Anatolian pronouns (ev, 'this'; ab, 'he/she/it'), conjunctions (ak and za, 'and'), prepositions (de, 'for'), and adverbs (osod, 'there').

The declension of nouns basically follows a familiar Anatolian language pattern:[5][11]

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| animate | inanimate | animate | inanimate | |

| Nominative | -Ø | -z (-ś) | ||

| Accusative | -o (?) | |||

| Genitive | -z (-ś) | -e | ||

| Dative / Locative | -i, -a (-o?) | -a | ||

| Ablative | -d (?) | |||

No verbs have yet been securely identified. A promising candidate is ozad, 'he offered', dedicated' (twice attested with object anathemataz, 'sacrifices'), a 3rd person singular preterite with the common Anatolian ending -d.

Like the neighbouring Pamphylian language, aphaeresis is frequent in names in Sidetic (e.g. Poloniw for Apollonios, Thandor for Athenodoros), as is syncope (e.g. Artmon for Artemon).

See also

References

- Pandey, Anshuman. "Introducing the Sidetic Script" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- Bossert, H. T. (1950). "Scrittura e lingua di Side in Pamfilia". PDP. 13: 32–46.

- Hesychius says the Greek equivalent is τέττιξ, or cicada: Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "'Tettix', in: A Greek-English Lexicon". Perseus.Tufts. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

- Nolle, Johannes (1983). "Die "Charaktere" im 3. Epidemienbuch des Hippokrates und Mnemon von Side". Epigraphica Anatolica. 2: 8.85–98.

- Pérez Orozco, Santiago. "La lengua Sidética. Una actualización [The Sidetic language. An update]". Retrieved 2021-11-13. (in Spanish)

- Woudhuizen, D. (2020). "On the Reading and Interpretation of the Two Longer Sidetic Inscriptions S I.2.1 and S I.2.5". Živa Antika. 70 (1/2): 17–34. doi:10.47054/ZIVA20701-2017w. S2CID 245576848. Retrieved 2021-11-13.

- Smith, William. "Mnemon (A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology)". Perseus Tufts. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- Nollé, Johannes (1983). "Die "Charaktere" im 3. Epidemienbuch des Hippokrates und Mnemon von Side". Epigraphica Anatolica. 1: 85–98.

- Rizza, Alfredo (2005). "A new epigraphic Document with Sidetic(?) signs". Kadmos. 44 (1–2): 60–74. doi:10.1515/KADM.2005.010. S2CID 162036788.

- Nollé (1983) p. 95.

- Касьян, А.С. (Alexei S. Kassian) (January 2013). "Сидетский язык [The Sidetic language] (in: Языки Мира : Реликтовые индоевропейские языки Передней и Центральной Азии [Languages of the world : Relict Indo-European languages of Near- and Central-Asia], pp. 175-177)". Moskva Academia. Retrieved 2021-04-14.

Further reading

- Zinko, Christian, and Zinko, Michaela. "Sidetisch – Ein Update zu Schrift und Sprache". In: Hrozný and Hittite: The First Hundred Years. Editors: Ronald I. Kim, Jana Mynářová, and Peter Pavúk. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2019. pp. 416–432. doi: https://doi-org.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1163/9789004413122_023 (In German)