Silesian language

Silesian[lower-alpha 1] or Upper Silesian is a West Slavic ethnolect[4][5] of the Lechitic group[2] spoken by a small percentage of people in Upper Silesia. Its vocabulary was significantly influenced by Central German due to the existence of numerous Silesian German speakers in the area prior to World War II and after.[6] Some regard it as one of the four major dialects of Polish,[7][8][9][10] while others classify it as a separate regional language, distinct from Polish.[4][11][12] The first mentions of Silesian as a distinct lect date back to the 16th century, and the first literature with Silesian characteristics to the 17th century.[13]

| Silesian | |

|---|---|

| Upper Silesian | |

| ślōnskŏ gŏdka ślůnsko godka | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɕlonskɔ ˈɡɔtka] |

| Native to | Poland (Silesian Voivodeship, Opole Voivodeship) Czech Republic (Moravia–Silesia, Jeseník) |

| Region | Silesia |

| Ethnicity | Silesians |

Native speakers | 457,900 (2021 census)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Latin script (Steuer's alphabet and ślabikŏrzowy szrajbōnek)[3] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | szl |

| Glottolog | sile1253 |

| ELP | Upper Silesian |

| Linguasphere | |

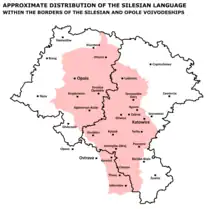

Distribution

Silesian speakers currently live in the region of Upper Silesia, which is split between southwestern Poland and the northeastern Czech Republic. At present Silesian is commonly spoken in the area between the historical border of Silesia on the east and a line from Syców to Prudnik on the west as well as in the Rawicz area.

Until 1945, Silesian was also spoken in enclaves in Lower Silesia, where the majority spoke Lower Silesian, a variety of Central German. The German-speaking population was either evacuated en masse by German forces towards the end of the war or deported by the new administration upon the Polish annexation of the Silesian Recovered Territories after its end. Before World War II, most Slavic-language speakers also knew German and, at least in eastern Upper Silesia, many German speakers were acquainted with Slavic Silesian.

According to the last official census in Poland in 2021, about 460,000[1] people declared Silesian as their native language, whereas in the country's census of 2011, the figure was about 510,000.[14] In the censuses in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, nearly 900,000 people declared Silesian nationality; Upper Silesia has almost five million inhabitants, with the vast majority in the Polish part speaking Polish and Czech in the Czech part and declaring themselves to be Poles in the former and Czechs in the latter.[14][15][16][17]

Grammar

Although the morphological differences between Silesian and Polish have been researched extensively, other grammatical differences have not been studied in depth.

A notable difference is in question-forming. In standard Polish, questions which do not contain interrogative words are formed either by using intonation or the interrogative particle czy. In Silesian, questions which do not contain interrogative words are formed by using intonation (with a markedly different intonation pattern than in Polish) or inversion (e.g. Je to na karcie?); there is no interrogative particle.

Example

According to Jan Miodek, standard Polish has always been used by Upper Silesians as a language of prayers.[18] The Lord's Prayer in Silesian, Polish, Czech, and English:

| Silesian[19] | Polish | Czech | English |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ôjcze nŏsz, kery jeżeś we niebie, |

Ojcze nasz, któryś jest w niebie, |

Otče náš, jenž jsi na nebesích, |

Our Father who art in heaven, |

Dialects of Silesian

Silesian has many dialects:

- Dialects spoken in areas which are now part of Poland, former Prussian Silesia:

- Kluczbork Silesian dialect (1)

- Opole Silesian dialect (2)

- Niemodlin Silesian dialect (3)

- Prudnik Silesian dialect (4)

- Gliwice Silesian dialect (5)

- Sulkovian Silesian dialect

- Borderland Silesian-Lesser Polish dialect (6a & 6b)

- Borderland Silesian-Lach dialect (9)

- Dialects spoken on both sides of the Czech–Polish border, former Austrian Silesia:

- Cieszyn Silesian dialect (7)

- Jabłonków Silesian dialect (8)

- Lach dialects spoken in areas which are now part of the Czech Republic, often considered linguistically apart from the ones mentioned above:

- Opava subdialect

- Ostrava subdialect

- Frenštát subdialect

Dialect vs. language

.jpg.webp)

Politicization

Opinions are divided among linguists regarding whether Silesian is a distinct language, a dialect of Polish, or in the case of Lach, a variety of Czech. The issue can be contentious, because some Silesians consider themselves to be a distinct nationality within Poland. When Czechs, Poles, and Germans each made claims to substantial parts of Silesia as constituting an integral part of their respective nation-states in the 19th and 20th centuries, the language of Slavic speaking Silesians became politicized.

Some, like Óndra Łysohorsky, a poet and author in Czechoslovakia, saw the Silesians as being their own distinct people, which culminated in his effort to create a literary standard he called the "Lachian language". Silesian inhabitants supporting the cause of each of these ethnic groups had their own robust network of supporters across Silesia's political borders which shifted over the course of the 20th century prior to the large-scale ethnic cleansing in the aftermath of World War II.

Views

Some linguists from Poland such as Jolanta Tambor,[20] Juan Lajo,[21] Tomasz Wicherkiewicz[22] and philosopher Jerzy Dadaczyński,[23] sociologist Elżbieta Anna Sekuła[24] and sociolinguist Tomasz Kamusella[25][26] support its status as a language. According to Stanisław Rospond, it is impossible to classify Silesian as a dialect of the contemporary Polish language because he considers it to be descended from the Old Polish language.[27] Other Polish linguists, such as Jan Miodek and Edward Polański, do not support its status as a language. Jan Miodek and Dorota Simonides, both of Silesian origin, prefer conservation of the entire range of Silesian dialects rather than standardization.[28] The German linguist Reinhold Olesch was eagerly interested in the "Polish vernaculars" of Upper Silesia and other Slavic varieties such as Kashubian and Polabian.[29][30][31][32]

United States Immigration Commission in 1911 classified it as one of the dialects of Polish.[33][34]

Most linguists writing in English, such as Alexander M. Schenker,[35] Robert A. Rothstein,[36] and Roland Sussex and Paul Cubberley[37] in their respective surveys of Slavic languages, list Silesian as a dialect of Polish, as does Encyclopædia Britannica.[38]

Gerd Hentschel wrote as a result of his paper about the question whether Silesian is a new Slavic language, that "Silesian ... can thus ... without doubt be described as a dialect of Polish" ("Das Schlesische ... kann somit ... ohne Zweifel als Dialekt des Polnischen beschrieben werden").[39][40][41]

In Czechia, disagreement exists concerning the Lach dialects which rose to prominence thanks to Óndra Łysohorsky and his translator Ewald Osers.[42] While some have considered it a separate language, most now view Lach as a dialect of Czech.[43][44][45]

Writing system

There have been a number of attempts at codifying the language spoken by Slavophones in Silesia. Probably the most well-known was undertaken by Óndra Łysohorsky when codifying the Lachian dialects in creating the Lachian literary language in the early 20th century.

Ślabikŏrzowy szrajbōnek is the relatively new alphabet created by the Pro Loquela Silesiana organization to reflect the sounds of all Silesian dialects. It was approved by Silesian organizations affiliated in Rada Górnośląska. Ubuntu translation is in this alphabet[46] as is some of the Silesian Wikipedia, although some of it is in Steuer's alphabet. It is used in a few books, including the Silesian alphabet book.[47]

- Letters: A, Ã, B, C, Ć, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, Ł, M, N, Ń, O, Ŏ, Ō, Ô, Õ, P, R, S, Ś, T, U, W, Y, Z, Ź, Ż.[47]

One of the first alphabets created specifically for Silesian was Steuer's Silesian alphabet, created in the Interwar period and used by Feliks Steuer for his poems in Silesian. The alphabet consists of 30 graphemes and eight digraphs:

- Letters: A, B, C, Ć, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, Ł, M, N, Ń, O, P, R, S, Ś, T, U, Ů, W, Y, Z, Ź, Ż

- Digraphs: Au, Ch, Cz, Dz, Dź, Dż, Rz, Sz

Based on the Steuer alphabet, in 2006 the Phonetic Silesian Alphabet was proposed:

- Letters: A, B, C, Ć, Č, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, Ń, O, P, R, Ř, S, Ś, Š, T, U, Ů, W, Y, Z, Ź, Ž.

Silesian's phonetic alphabet replaces the digraphs with single letters (Sz with Š, etc.) and does not include the letter Ł, whose sound can be represented phonetically with U. It is therefore the alphabet that contains the fewest letters. Although it is the most phonetically logical, it did not become popular with Silesian organizations, with the argument that it contains too many caron diacritics and hence resembles the Czech alphabet. Large parts of the Silesian Wikipedia, however, are written in Silesian's phonetic alphabet.

Sometimes other alphabets are also used, such as the "Tadzikowy muster" (for the National Dictation Contest of the Silesian language) or the Polish alphabet, but writing in this alphabet is problematic as it does not allow for the differentiation and representation of all Silesian sounds.[47]

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Upper Silesia |

|---|

|

| Cuisine |

| Literature |

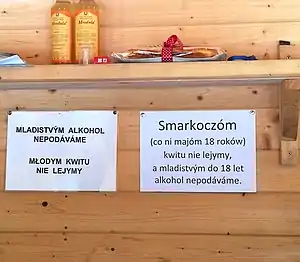

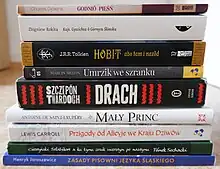

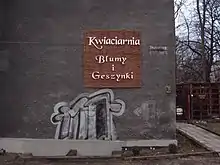

Silesian has recently seen an increased use in culture, for example:

- Wachtyrz.eu, online news and information platform (founded in January 2018)[48]

- YouTube personalities such as Niklaus Pieron[49]

- TV and radio stations (for example: TV Silesia, Sfera TV, TVP Katowice, Slonsky Radio,[50] Radio Piekary, Radio Silesia, Radio Fest);

- Music groups (for example: Jan Skrzek, Krzysztof Hanke, Hasiok, Dohtor Miód, FEET);

- Theatre[51] (for example: Polterabend in Silesian Theatre[52]);

- Plays[53]

- Film (for example: The Sinful Life of Franciszek Buła ("Grzeszny żywot Franciszka Buły")

- Books (for example, the so-called Silesian Bible; poetry: "Myśli ukryte" by Karol Gwóźdź)

- Teaching aides (for example, a Silesian basal reader)[54]

Recognition

In 2003, the National Publishing Company of Silesia (Narodowa Oficyna Śląska) commenced operations.[55] This publisher was founded by the Alliance of the People of the Silesian Nation (Związek Ludności Narodowości Śląskiej) and it prints books about Silesia and books in Silesian language.

In July 2007, the Slavic Silesian language was given the ISO 639-3 code szl.[56]

On 6 September 2007, 23 politicians of the Polish parliament made a statement about a new law to give Silesian the official status of a regional language.[57]

The first official National Dictation Contest of the Silesian language (Ogólnopolskie Dyktando Języka Śląskiego) took place in August 2007. In dictation as many as 10 forms of writing systems and orthography have been accepted.[58][59]

On 30 January 2008 and in June 2008, two organizations promoting Silesian language were established: Pro Loquela Silesiana and Tôwarzistwo Piastowaniô Ślónskij Môwy "Danga".[60]

On 26 May 2008, the Silesian Wikipedia was founded.[61]

On 30 June 2008 in the edifice of the Silesian Parliament in Katowice, a conference took place on the status of the Silesian language. This conference was a forum for politicians, linguists, representatives of interested organizations and persons who deal with the Silesian language. The conference was titled "Silesian – Still a Dialect or Already a Language?" (Śląsko godka – jeszcze gwara czy jednak już język?).[62]

In 2012, the Ministry of Administration and Digitization registered the Silesian language in Annex 1 to the Regulation on the state register of geographical names;[63] however, in a November 2013 amendment to the regulation, Silesian is not included.[64]

See also

Literature

- Paul Weber. 1913. Die Polen in Oberschlesien: eine statistische Untersuchung. Verlagsbuchhandlung von Julius Springer in Berlin (in German)

- Norbert Morciniec. 1989. Zum Wortgut deutscher Herkunft in den polnischen Dialekten Schlesiens. Zeitschrift für Ostforschung, Bd. 83, Heft 3 (in German)

- Joseph Partsch. 1896. Schlesien: eine Landeskunde für das deutsche Volk. T. 1., Das ganze Land (die Sprachgrenze 1790 und 1890; pp. 364–367). Breslau: Verlag Ferdinand Hirt. (in German)

- Joseph Partsch. 1911. Schlesien: eine Landeskunde für das deutsche Volk. T. 2., Landschaften und Siedelungen. Breslau: Verlag Ferdinand Hirt. (in German)

- Lucyna Harc et al. 2013. Cuius Regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia (c. 1000–2000) vol. 1., The Long Formation of the Region Silesia (c. 1000–1526). Wrocław: eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-927132-1-0

- Lucyna Harc et al. 2014. Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia (c. 1000–2000) vol. 2., The Strengthening of Silesian Regionalism (1526–1740). Wrocław: eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-927132-6-5

- Lucyna Harc et al. 2014. Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia (c. 1000–2000) vol. 4., Region Divided: Times of Nation-States (1918–1945). Wrocław: eBooki.com.pl ISBN 978-83-927132-8-9

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2014. Ślōnsko godka / The Silesian Language. Zabrze: NOS, 196 pp. ISBN 9788360540220

- Tomasz Kamusella and Motoki Nomachi. 2014. The Long Shadow of Borders: The Cases of Kashubian and Silesian in Poland (pp 35–60). The Eurasia Border Review. Vol 5, No 2, Fall.[65]

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2014. Warszawa wie lepiej Ślązaków nie ma. O dyskryminacji i języku śląskim [Warsaw Knows Better – The Silesians Don't Exist: On Discrimination and the Silesian Language]. Zabrze, Poland: NOS, 174 pp. ISBN 9788360540213.

- Review: Michael Mose. 2013. Zeitschrift für Slawistik (pp 118–119). Vol 58, No 1. Potsdam: Universität Potsdam.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2013. The Silesian Language in the Early 21st Century: A Speech Community on the Rollercoaster of Politics (pp 1–35). Die Welt der Slaven. Vol 58, No 1.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2011. Silesian in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A Language Caught in the Net of Conflicting Nationalisms, Politics, and Identities (pp 769–789). 2011. Nationalities Papers. No 5.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2011). "Language: Talking or trading blows in the Upper Silesian industrial basin?". Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication. 30 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1515/mult.2011.002. ISSN 1613-3684. S2CID 144109393.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2009. Échanges de paroles ou de coups en Haute-Silésie: la langue comme 'lieu' de contacts et de luttes interculturels [Exchange of Words or Blows in Upper Silesia: Language as a "Place" of Contacts and Intercultural Struggles] (pp 133–152). Cultures d'Europe centrale. No 8: Lieux communs de la multiculturalité urbaine en Europe centrale, ed by Delphine Bechtel and Xavier Galmiche. Paris: CIRCE.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2007. Uwag kilka o dyskryminacji Ślązaków i Niemców górnośląskich w postkomunistycznej Polsce [A Few Remarks on the Discrimination of the Silesians and Upper Silesia's Germans in Postcommunist Poland]. Zabrze, Poland: NOS, 28 pp. ISBN 978-83-60540-68-8.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2006. Schlonzsko: Horní Slezsko, Oberschlesien, Górny Śląsk. Esej o regionie i jego mieszkańcach [Schlonzsko: Upper Silesia. An Essay on the Region and Its Inhabitants] (2nd, corrected and enlarged edition). Zabrze, Poland: NOS, 148 pp. ISBN 978-83-60540-51-0.

- Review: Anon. 2010. The Sarmatian Review. Sept. (p 1530).

- Review: Svetlana Antova. 2007. Bulgarian Ethnology / Bulgarska etnologiia. No 4 (pp 120–121).

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2009. Codzienność komunikacyjno-językowa na obszarze historycznego Górnego Śląska [The Everyday Language Use in Historical Upper Silesia] (pp 126–156). In: Robert Traba, ed. Akulturacja/asymilacja na pograniczach kulturowych Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej w XIX i XX wieku [Acculturation/Assimilation in the Cultural Borderlands of East-Central Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries] (vol 1: Stereotypy i pamięć [Stereotypes and memory]). Warsaw: Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN and Niemiecki Instytut Historyczny.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2009. Czy śląszczyzna jest językiem? Spojrzenie socjolingwistyczne [Is Silesian a Language? A Sociolinguistic View] (pp 27–35). In: Andrzej Roczniok, ed. Śląsko godka – jeszcze gwara czy jednak już język? / Ślōnsko godko – mundart jeszcze eli już jednak szpracha. Zabrze: NOŚ.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2006. Schlonzska mowa. Język, Górny Śląsk i nacjonalizm (Vol II) [Silesia and Language: Language, Upper Silesia and Nationalism, a collection of articles on various social, political and historical aspects of language use in Upper Silesia]. Zabrze, Poland: NOS, 151 pp. ISBN 83-919589-2-2.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2005. Schlonzska mowa. Język, Górny Śląsk i nacjonalizm (Vol I) [Silesia and Language: Language, Upper Silesia and Nationalism, a collection of articles on various social, political and historical aspects of language use in Upper Silesia]. Zabrze, Poland: NOS, 187 pp. ISBN 83-919589-2-2.

- Review: Kai Struve. 2006. Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung. No 4. Marburg, Germany: Herder-Institut (pp 611–613).

- Review: Kai Struve. 2007. Recenzyjo Instituta Herdera [Herder-Institute’s Review] (pp 26–27). Ślůnsko Nacyjo. No 5, Jul. Zabrze: NOŚ.

- Review: Jerzy Tomaszewski. 2007. Czy istnieje naród śląski? [Does the Silesian Nation Exist] (pp 280–283). Przegląd Historyczny. No 2. Warsaw: DiG and University of Warsaw.

- Review: Jerzy Tomaszewski. 2007. Czy istnieje naród śląski? [Does the Silesian Nation Exist] (pp 8–12). 2007. Ślůnsko Nacyjo. No 12, Dec. Zabrze: NOŚ.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2004. The Szlonzokian Ethnolect in the Context of German and Polish Nationalisms (pp. 19–39). Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism. No 1. London: Association for the Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9469.2004.tb00056.x.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2001. Schlonzsko: Horní Slezsko, Oberschlesien, Górny Śląsk. Esej o regionie i jego mieszkańcach [Schlonzsko: Upper Silesia. An Essay on the Region and Its Inhabitants]. Elbląg, Poland: Elbląska Oficyna Wydawnicza, 108 pp. ISBN 83-913452-2-X.

- Review: Andreas R Hofmann. 2002. Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung. No 2. Marburg, Germany: Herder-Institut (p 311).

- Review: Anon. 2002. Esej o naszym regionie [An Essay on Our region] (p 4). Głos Ludu. Gazeta Polaków w Republice Czeskiej. No 69, 11 June. Ostrava, Czech Republic: Vydavatelství OLZA.

- Review: Walter Żelazny eo:Walter Żelazny. 2003. Niech żyje śląski lud [Long Live the Silesian People] (pp 219–223). Sprawy Narodowościowe. No 22. Poznań, Poland: Zakład Badań Narodowościowych PAN.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 1999. Język a Śląsk Opolski w kontekście integracji europejskiej [Language and Opole Silesia in the Context of European Integration] (pp 12–19). Śląsk Opolski. No 3. Opole, Poland: Instytut Śląski.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 1998. Das oberschlesische Kreol: Sprache und Nationalismus in Oberschlesien im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert [The Upper Silesian Creole: Language and Nationalism in the 19th and 20th Centuries] (pp 142–161). In: Markus Krzoska und Peter Tokarski, eds. . Die Geschichte Polens und Deutschlands im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Ausgewählte Baiträge. Osnabrück, Germany: fibre.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 1998. Kreol górnośląski [The Upper Silesian Creole] (pp 73–84). Kultura i Społeczeństwo. No 1. Warsaw, Poland: Komitet Socjologii ISP PAN.

- Andrzej Roczniok and Tomasz Kamusella. 2011. Sztandaryzacyjo ślōnski godki / Standaryzacja języka śląskiego [The Standardization of the Silesian Language] (pp 288–294). In: I V Abisigomian, ed. Lingvokul’turnoe prostranstvo sovremennoi Evropy cherez prizmu malykh i bolshikh iazykov. K 70-letiiu professora Aleksandra Dimitrievicha Dulichenko (Ser: Slavica Tartuensis, Vol 9). Tartu: Tartu University.

- Robert Semple. London 1814. Observations made on a tour from Hamburg through Berlin, Gorlitz, and Breslau, to Silberberg; and thence to Gottenburg (pp. 122–123)

Notes

-

- Steuer's Silesian alphabet: ślůnsko godka, [ˈɕlonskɔ ˈɡɔtka]

- Silesian primer alphabet: ślōnskŏ gŏdka, [ˈɕlonskɔ ˈɡɔtka]

- Czech: slezština

- Polish: język śląski, śląszczyzna

- German: Schlonsakisch, Wasserpolnisch

References

- "Wstępne wyniki Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2021 w zakresie struktury narodowo-etnicznej oraz języka kontaktów domowych" [Report of results: National Census of Population and Housing, 2021.] (PDF). Central Statistical Office of Poland (in Polish). 2023.

- "Ethnologue report for language code:

szl". Ethnologue. Languages of the World. - Silesian language at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- Ptak, Alicja (28 December 2022). "Supermarket introduces bilingual Polish-Silesian signs". Kraków: Notes from Poland. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- Tilles, Daniel (13 April 2023). "New census data reveal changes in Poland's ethnic and linguistic makeup". Kraków: Notes from Poland. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2013. The Silesian Language in the Early 21st Century: A Speech Community on the Rollercoaster of Politics (pp 1–35). Die Welt der Slaven. Vol 58, No 1.

- Gwara Śląska – świadectwo kultury, narzędzie komunikacji. Jolanta Tambor (eds.); Aldona Skudrzykowa. Katowice: „Śląsk". 2002. ISBN 83-7164-314-4. OCLC 830518005.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - „Słownik gwar Śląskich". Opole, Bogusław Wyderka (eds.)

- „Dialekt śląski" author: Feliks Pluta, publication: Wczoraj, Dzisiaj, Jutro. – 1996, no 1/4, pp 5–19

- „Fenomen śląskiej gwary" author: Jan Miodek publication: Śląsk. – 1996, no 5, pp 52

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Oxford 1996 pp 1233

- Jolanta Tambor. Opinia merytoryczna na temat poselskiego projektu ustawy o zmianie Ustawy o mniejszościach narodowych i etnicznych oraz o języku regionalnym, a także niektórych innych ustaw, Warszawa 3 maja 2011 r. (English: Substantive opinion on the parliamentary bill amending the Act on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional language, as well as some other acts, Warsaw, May 3, 2011.)

- "Najstarszy zabytek śląskiej literatury? (Część 1)". Wachtyrz.eu (in Polish). 18 August 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

Najstarsze dokumenty będące świadectwem wyodrębniania się dialektów śląskich w oddzielną grupę pochodzą z XVI w. Należą do nich m. in. list Ambrożego Szklorza z Olesna opublikowany przez Władysława Nehringa (Nehring 1902 [1]) i rachunek ślusarza Matysa Hady opublikowany przez Leona Derlicha i Andrzeja Siuduta (Derlich, Siudut 1957). Są to jednak zabytki piśmiennictwa, a nie literatury – początków tej drugiej można się doszukiwać na Śląsku w najlepszym razie dopiero w wieku XVII.

- "Raport z wyników: Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011" [Report of results: National Census of Population and Housing, 2011.] (PDF). Central Statistical Office of Poland (in Polish). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012.

- "Obyvatelstvo podle národnosti podle krajů" (PDF). Czech Statistical Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012.

- "Národnost ve sčítání lidu v českých zemích" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- National Minorities in the Slovak Republic – Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Slovak Republic

- "Jan Miodek: Dyskusja o języku śląskim w piśmie jest żenująca". 26 March 2011.

- "Endangered Languages Project – Upper Silesian – Ôjcze nasz". www.endangeredlanguages.com. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Ekspertyza naukowa prof. UŚ Dr hab. Jolanty Tambor" (en: "Scientific expertise by Juan Lajo"), 2008

- "Ekspertyza naukowa pana Juana Lajo" (en: "Scientific expertise by Juan Lajo"), 2008

- "Ekspertyza naukowa dra Tomasza Wicherkiewicza" (en: "Scientific expertise by Tomasz Wicherkiewicz"), 2008

- "Ekspertyza naukowa ks. dra hab. Jerzego Dadaczyńskiego") (en: "Scientific expertise by Jerzy Dadaczyński"), 2008

- "Ekspertyza naukowa dr Elżbiety Anny Sekuły" (en: "Scientific expertise by Elżbieta Anna Sekuła"), 2008

- Tomasz Kamusella (2005). Schlonzska mowa – Język, Górny Śląsk i nacjonalizm [Silesian speech – language, Upper Silesia and nationalism] (in Polish). ISBN 83-919589-2-2.

- Tomasz Kamusella (2003). "The Szlonzoks and their Language: Between Germany, Poland and Szlonzokian Nationalism" (PDF). European University Institute — Department of History and Civilization and Opole University.

- "Polszczyzna śląska" – Stanisław Rospond, Ossolineum 1970, p. 80–87

- "The Silesian Language in the Early 21st Century: A Speech Community on the Rollercoaster of Politics Tomasz Kamusella". xlibx.com. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Ernst Eichler (1999). Neue deutsche Biographie [New German biography] (in German). p. 519.

- Reinhold Olesch (1987). Zur schlesischen Sprachlandschaft: Ihr alter slawischer Anteil [On the Silesian language landscape: their old Slavic share] (in German). pp. 32–45.

- Joanna Rostropowicz. Śląski był jego językiem ojczystym: Reinhold Olesch, 1910–1990 [Silesian was his mother tongue: Reinhold Olesch, 1910–1990] (in Polish).

- Krzysztof Kluczniok, Tomasz Zając (2004). Śląsk bogaty różnorodnością – kultur, narodów i wyznań. Historia lokalna na przykładzie wybranych powiatów, miast i gmin [Silesia, a rich diversity – of cultures, nations and religions. Local history, based on selected counties, cities and municipalities]. Urząd Gm. i M. Czerwionka-Leszczyny, Dom Współpracy Pol.-Niem., Czerwionka-Leszczyny. ISBN 83-920458-5-8.

- Dillingham, William Paul; Folkmar, Daniel; Folkmar, Elnora (1911). Dictionary of Races or Peoples. United States. Immigration Commission (1907–1910). Washington, D.C.: Washington, Government Printing Office. pp. 104–105.

- Dillingham, William Paul; Folkmar, Daniel; Folkmar, Elnora (1911). Dictionary of Races or Peoples. Washington, D.C.: Washington, Government Printing Office. p. 128.

- Alexander M. Schenker, "Proto-Slavonic", The Slavonic Languages (1993, Routledge), pages 60–121.

- Robert A. Rothstein, "Polish", The Slavonic Languages (1993, Routledge), pages 686–758.

- Roland Sussex & Paul Cubberley, The Slavic Languages (2006, Cambridge University Press).

- "Silesian". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Gerd Hentschel. "Schlesisch" (PDF) (in German).

- Gerd Hentschel (2001). "Das Schlesische – eine neue (oder auch nicht neue) slavische Sprache?". Mitteleuropa – Osteuropa. Oldenburger Beiträge zur Kultur und Geschichte Ostmitteleuropas. P. Lang. ISBN 3-631-37648-0.

- Gerd Hentschel: Das Schlesische – eine neue (oder auch nicht neue) slavische Sprache?, Mitteleuropa – Osteuropa. Oldenburger Beiträge zur Kultur und Geschichte Ostmitteleuropas. Band 2, 2001 ISBN 3-631-37648-0

- Ewald Osers (1949). Silesian Idiom and Language. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dušan Šlosar. "Tschechisch" (PDF) (in German).

- Aleksandr Dulichenko. "Lexikon der Sprachen des europäischen Ostens" [Encyclopedia of Languages of Eastern Europe] (PDF) (in German).

- Pavlína Kuldanová (2003). "Útvary českého národního jazyka" [Structures of the Czech National Language] (in Czech). Archived from the original on 2 September 2012.

- ""Silesian Ubuntu Translation" team". Launchpad.net. 5 July 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Mirosław Syniawa: Ślabikŏrz niy dlŏ bajtli. Pro Loquela Silesiana. ISBN 978-83-62349-01-2

- "Home". wachtyrz.eu.

- "Niklaus Pieron – YouTube". www.youtube.com.

- "SlonskyRadio". SlonskyRadio.

- "Po śląsku w kaplicy" [Once in the chapel of Silesia] (in Polish). e-teatr.pl. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "Stanisław Mutz – Polterabend" (in Polish). Silesian Theatre. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007.

- Jednoaktówki po śląsku

- (in Silesian) Przemysław Jedlicki, Mirosław Syniawa (13 February 2009). "Ślabikorz dlo Slůnzokůw". Gazeta Wyborcza Katowice. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009.

- "Narodowa Oficyna Śląska" [National Publishing Company of Silesia] (in Silesian). Archived from the original on 4 September 2007.

- "ISO documentation of Silesian language". SIL International.

- Dziennik Zachodni (2008). "Śląski wśród języków świata" [Silesian Among the Languages of the World] (in Polish). Our News Katowice.

- (in Silesian and Polish) "National Dictation contest of the Silesian language".

- Ortography: diacritic, Czech, phonetic, Hermannowa, Polish, Polish plus, Steuer's, Tadzikowa, Wieczorkowa, multisigned.

- "Śląski wśród języków świata" [The Silesian language is a foreign language]. Dziennik Zachodni (in Polish). 2008. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008.

- "Śląska Wikipedia już działa" [Silesian Wikipedia already operating]. Gazeta Wyborcza-Gospodarka (in Polish). 2008.

- (in Polish)

"Katowice: konferencja dotycząca statusu śląskiej mowy" [Katowice: Conference concerning the status of the Silesian language]. Polish Wikinews. 1 July 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

"Katowice: konferencja dotycząca statusu śląskiej mowy" [Katowice: Conference concerning the status of the Silesian language]. Polish Wikinews. 1 July 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2012. - Dz.U. 2012 nr 0 poz. 309 – Internet System of Legal Acts

- Dz. U. z 2013 r. poz. 1346

- "The Long Shadow of Borders: The Cases of Kashubian and Silesian in Poland"

- Tomasz Kamusella (2013): "Ślōnsko godka. The silesian language" - Review by Mark Brüggemann

External links

- (in Silesian) Jynzyk S'loonski