Grapheme

In linguistics, a grapheme is the smallest functional unit of a writing system.[1] The word grapheme is derived from Ancient Greek γράφω (gráphō) 'write' and the suffix -eme by analogy with phoneme and other names of emic units. The study of graphemes is called graphemics. The concept of graphemes is abstract and similar to the notion in computing of a character. By comparison, a specific shape that represents any particular grapheme in a given typeface is called a glyph.

| Part of a series on |

| Reading |

|---|

|

Conceptualization

There are two main opposing grapheme concepts.[2]

In the so-called referential conception, graphemes are interpreted as the smallest units of writing that correspond with sounds (more accurately phonemes). In this concept, the sh in the written English word shake would be a grapheme because it represents the phoneme /ʃ/. This referential concept is linked to the dependency hypothesis that claims that writing merely depicts speech.

By contrast, the analogical concept defines graphemes analogously to phonemes, i.e. via written minimal pairs such as shake vs. snake. In this example, h and n are graphemes because they distinguish two words. This analogical concept is associated with the autonomy hypothesis which holds that writing is a system in its own right and should be studied independently from speech. Both concepts have weaknesses.[3]

Some models adhere to both concepts simultaneously by including two individual units,[4] which are given names such as graphemic grapheme for the grapheme according to the analogical conception (h in shake), and phonological-fit grapheme for the grapheme according to the referential concept (sh in shake).[5]

In newer concepts, in which the grapheme is interpreted semiotically as a dyadic linguistic sign,[6] it is defined as a minimal unit of writing that is both lexically distinctive and corresponds with a linguistic unit (phoneme, syllable, or morpheme).[7]

Notation

Graphemes are often notated within angle brackets: ⟨a⟩, ⟨b⟩, etc.[8] This is analogous to both the slash notation (/a/, /b/) used for phonemes and to the square bracket notation used for phonetic transcriptions ([a], [b]).

Glyphs

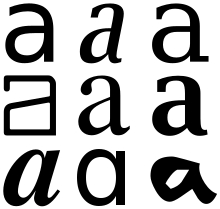

In the same way that the surface forms of phonemes are speech sounds or phones (and different phones representing the same phoneme are called allophones), the surface forms of graphemes are glyphs (sometimes graphs), namely concrete written representations of symbols (and different glyphs representing the same grapheme are called allographs).

Thus, a grapheme can be regarded as an abstraction of a collection of glyphs that are all functionally equivalent.

For example, in written English (or other languages using the Latin alphabet), there are two different physical representations of the lowercase Latin letter "a": "a" and "ɑ". Since, however, the substitution of either of them for the other cannot change the meaning of a word, they are considered to be allographs of the same grapheme, which can be written ⟨a⟩. Similarly, the grapheme corresponding to "Arabic numeral zero" has a unique semantic identity and Unicode value U+0030 but exhibits variation in the form of slashed zero. Italic and bold face forms are also allographic, as is the variation seen in serif (as in Times New Roman) versus sans-serif (as in Helvetica) forms.

There is some disagreement as to whether capital and lower case letters are allographs or distinct graphemes. Capitals are generally found in certain triggering contexts that do not change the meaning of a word: a proper name, for example, or at the beginning of a sentence, or all caps in a newspaper headline. In other contexts, capitalization can determine meaning: compare, for example Polish and polish: the former is a language, the latter is for shining shoes.

Some linguists consider digraphs like the ⟨sh⟩ in ship to be distinct graphemes, but these are generally analyzed as sequences of graphemes. Non-stylistic ligatures, however, such as ⟨æ⟩, are distinct graphemes, as are various letters with distinctive diacritics, such as ⟨ç⟩.

Identical glyphs may not always represent the same grapheme. For example, the three letters ⟨A⟩, ⟨А⟩ and ⟨Α⟩ appear identical but each has a different meaning: in order, they are the Latin letter A, the Cyrillic letter Azǔ/Азъ and the Greek letter Alpha. Each has its own code point in Unicode: U+0041 A LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A, U+0410 А CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER A and U+0391 Α GREEK CAPITAL LETTER ALPHA.

Types of grapheme

The principal types of graphemes are logograms (more accurately termed morphograms[9]), which represent words or morphemes (for example Chinese characters, the ampersand "&" representing the word and, Arabic numerals); syllabic characters, representing syllables (as in Japanese kana); and alphabetic letters, corresponding roughly to phonemes (see next section). For a full discussion of the different types, see Writing system § Functional classification.

There are additional graphemic components used in writing, such as punctuation marks, mathematical symbols, word dividers such as the space, and other typographic symbols. Ancient logographic scripts often used silent determinatives to disambiguate the meaning of a neighboring (non-silent) word.

Relationship with phonemes

As mentioned in the previous section, in languages that use alphabetic writing systems, many of the graphemes stand in principle for the phonemes (significant sounds) of the language. In practice, however, the orthographies of such languages entail at least a certain amount of deviation from the ideal of exact grapheme–phoneme correspondence. A phoneme may be represented by a multigraph (sequence of more than one grapheme), as the digraph sh represents a single sound in English (and sometimes a single grapheme may represent more than one phoneme, as with the Russian letter я or the Spanish c). Some graphemes may not represent any sound at all (like the b in English debt or the h in all Spanish words containing the said letter), and often the rules of correspondence between graphemes and phonemes become complex or irregular, particularly as a result of historical sound changes that are not necessarily reflected in spelling. "Shallow" orthographies such as those of standard Spanish and Finnish have relatively regular (though not always one-to-one) correspondence between graphemes and phonemes, while those of French and English have much less regular correspondence, and are known as deep orthographies.

Multigraphs representing a single phoneme are normally treated as combinations of separate letters, not as graphemes in their own right. However, in some languages a multigraph may be treated as a single unit for the purposes of collation; for example, in a Czech dictionary, the section for words that start with ⟨ch⟩ comes after that for ⟨h⟩.[10] For more examples, see Alphabetical order § Language-specific conventions.

See also

- Character (computing) – Primitive data type

- Grapheme–color synesthesia – Synesthesia that associates numbers or letters with colors

- Sign (semiotics) – Something that communicates meaning

References

- Coulmas, F. (1996), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell, p. 174

- Kohrt, M. (1986), The term 'grapheme' in the history and theory of linguistics. In G. Augst (Ed.), New trends in graphemics and orthography. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 80–96. doi:10.1515/9783110867329.80

- Lockwood, D. G. (2001), Phoneme and grapheme: How parallel can they be? LACUS Forum 27, 307–316.

- Rezec, O. (2013), Ein differenzierteres Strukturmodell des deutschen Schriftsystems. Linguistische Berichte 234, pp. 227–254.

- Herrick, E. M. (1994), Of course a structural graphemics is possible! LACUS Forum 21, pp. 413–424.

- Fedorova, L. (2013), The development of graphic representation in abugida writing: The akshara’s grammar. Lingua Posnaniensis 55:2, pp. 49–66. doi:10.2478/linpo-2013-0013

- Meletis, D. (2019), The grapheme as a universal basic unit of writing. Writing Systems Research. doi:10.1080/17586801.2019.1697412

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, second edition, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 196

- Joyce, T. (2011), The significance of the morphographic principle for the classification of writing systems, Written Language and Literacy 14:1, pp. 58–81. doi:10.1075/wll.14.1.04joy

- Zeman, Dan. "Czech Alphabet, Code Page, Keyboard, and Sorting Order". Old-site.clsp.jhu.edu. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.