Mexico City Metro

The Mexico City Metro (Spanish: Metro de la Ciudad de México) is a rapid transit system that serves the metropolitan area of Mexico City, including some municipalities in the State of Mexico. Operated by the Sistema de Transporte Colectivo (STC), it is the second largest metro system in North America after the New York City Subway.

| Mexico City Metro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

| Overview | |||

| Native name | Sistema de Transporte Colectivo - Metro | ||

| Owner | Sistema de Transporte Colectivo (STC) | ||

| Area served | Greater Mexico City | ||

| Locale | Mexico City | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 12[1] | ||

| Line number | 1-9, 12, A, B | ||

| Number of stations | 195[1] | ||

| Daily ridership | 4,534,383 (2019)[2] | ||

| Annual ridership | 1.655 billion (2019)[2] | ||

| Website | Metro de la Ciudad de México | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 4 September 1969[3] | ||

| Operator(s) | Sistema de Transporte Colectivo (STC) | ||

| Number of vehicles | 390[4] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 200.9 km (124.8 mi) in revenue service; (226.5 km (140.7 mi) considering maintenance tracks)[5] | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge (2 lines); and roll ways along the outside of conventional standard gauge track (Rubber-tired metro) (10 lines) | ||

| |||

The inaugural STC Metro line was 12.7 kilometres (7.9 mi) long, serving 16 stations, and opened to the public on 4 September 1969.[3] The system has expanded since then in a series of fits and starts. As of 2015, the system has 12 lines,[1] serving 195 stations,[1] and 226.49 kilometres (140.73 mi) of route.[1] Ten of the lines are rubber-tired. Instead of traditional steel wheels, they use pneumatic traction, which is quieter and rides smoother in Mexico City's unstable soils. The system survived the 1985 Mexico City earthquake.[6]

Of the STC Metro's 195 stations,[1] 44 serve two or more lines (correspondencias or transfer stations).[7] Many stations are named for historical figures, places, or events in Mexican history. It has 115 underground stations[1] (the deepest of which are 35 metres [115 ft] below street level); 54 surface stations[1] and 26 elevated stations.[1] All lines operate from 5 a.m. to midnight. At the end of 2007, the Federal District government announced the construction of the most recent STC Metro line, Line 12, which was built to run approximately 26 kilometres (16 mi)[8] towards the southeastern part of the city, connecting with Lines 7, 3, 2 and 8. This line opened on 30 October 2012.[9]

The Metro has figured in Mexico's cultural history, as the inspiration for a musical composition for strings, "Metro Chabacano"[10] and Rodrigo "Rockdrigo" González's 1982 song, "Metro Balderas". It was also a filming location for the 1990 Hollywood movie Total Recall.[11] Public intellectual Carlos Monsiváis has commented on the cultural importance of the Metro, "a space for collective expression, where diverse social sectors are compelled to mingle every day".[12]

History

Concept of the Metro and early plans

By the second half of the twentieth century, Mexico City had serious public transport issues, with congested main roads and highways, especially in the downtown zone, where 40 percent of the daily trips in the city were concentrated. 65 of the 91 lines of bus and electric transport served this area. With four thousand units in addition to 150,000 personal automobile peak hours, the average speed was less than walking pace.

The principal promoter of the construction of the Mexico City Metro was engineer Bernardo Quintana, who was in charge of the construction company Ingenieros Civiles y Asociados (Civil Engineers and Associates). He carried out a series of studies that resulted in a draft plan which would ultimately lead to the construction of the Mexico City Metro. This plan was shown to different authorities of Mexico City but it was not made official until 29 April 1967, when the Government Gazette ("Diario Oficial de la Federación") published the presidential decree that created a public decentralized organism, the Sistema de Transporte Colectivo, with the proposal to build, operate and run an underground rapid transit network as part of Mexico City's public transport system.[13]

The Mexico City Metro benefited from a great amount of technical assistance made available by France. RATP's engineering branch SOFRETU played a major role in its initial planning and the design of the first lines, hence the choice of tyre/rail technology.

On 19 June 1967, at the crossroads of Chapultepec Avenue with Avenida Bucareli, the inauguration ceremony for the Mexico City Metro took place. Two years later, on 4 September 1969, an orange train made the inaugural trip between Zaragoza and Insurgentes stations, thus beginning daily operation up to today.[14]

First stage (1967–1972)

The first stage of construction comprised the construction, done by Grupo ICA, and inauguration of lines 1, 2 and 3. This stage involved engineers, geologists, mechanics, civil engineers, chemists, hydraulic and sanitation workers, electricians, archaeologists, and biologists; specialists in ventilation, statistics, computation, and in traffic and transit; accountants, economists, lawyers, workers and laborers. Between 1,200 and 4,000 specialists and 48,000 workers participated, building at least one kilometre (0.62 mi) of track per month, the fastest rate of construction ever for a subway.

During this stage of construction workers uncovered two archaeological ruins, one Aztec idol, and the bones of a mammoth (on display at Talismán station).[15]

By the end of the first stage, namely on 10 June 1972, the STC Metro had 48 stations and a total length of 41.41 kilometres (25.73 mi): Line 1 ran from Observatorio to Zaragoza, Line 2 from Tacuba southwest to Tasqueña and line 3 from Tlatelolco to Hospital General in the south, providing quick access to the General Hospital of Mexico.

Second stage (1977–1982)

No further progress was reached during President Luis Echeverría's government, but during José López Portillo's administration, a second stage began. The Comisión Ejecutiva del Metro (Executive Technical Commission of Mexico City Metro) was created in order to be in charge of expanding the STC Metro within the metropolitan area of Mexico City.

Works began with the expansion of Line 3 towards the north from Tlatelolco to La Raza in 1978 and to the current terminal Indios Verdes in 1979, and towards the south from Hospital General to Centro Médico in 1980 and to Zapata months later. Construction of lines 4 and 5 was begun and completed on 26 May – 30 August 1982, respectively; the former from Martín Carrera to Santa Anita and the latter from Politécnico to Pantitlán. Line 4 was the first STC Metro line built as an elevated track, owing to the lower density of big buildings.

Third stage (1983–1985), and the 1985 earthquake

This construction stage took place from the beginning of 1983 through the end of 1985. Lines 1, 2 and 3 were expanded to their current lengths, and new lines 6 and 7 were built. The length of the network was increased by 35.29 kilometres (21.93 mi) and the number of stations to 105.

Line 3's route was expanded from Zapata station to Universidad station on 30 August 1983. Line 1 was expanded from Zaragoza to the current terminal Pantitlán, and line 2 from Tacuba to the current terminal Cuatro Caminos. These last two were both inaugurated on 22 August 1984.

Line 6's route first ran from El Rosario to Instituto del Petróleo; Line 7 was opened from Tacuba to Barranca del Muerto and runs along the foot of the Sierra de las Cruces mountain range that surrounds the Valley of Mexico at its west side, outside of the ancient lake zone. This made it possible for Line 7 to be built as a deep-bore tunnel.

On the morning of 19 September 1985, a magnitude 8.0 earthquake struck Mexico City. Many buildings as well as streets were left with major damage making transportation on the ground difficult, but the STC Metro was not damaged because a rectangular structure had been used instead of arches, making it resistant to earthquakes, thus proving to be a safe means of transportation in a time of crisis.

On the day of the quake, the Metro stopped service and completely shut down for fear of electrocution. This caused people to get out of the tunnels from wherever they were and onto the street to try to get where they were going.[16] At the time, the Metro had 101 stations, with 32 closed to the public in the weeks after the event. On Line 1, there was no service in stations Merced, Pino Suárez, Isabel la Católica, Salto del Agua, Balderas or Cuauhtémoc. On Line 2, there was no service between stations Bellas Artes and Tasqueña. On Line 3 only Juárez and Balderas were closed. Line 4 continued to operate normally. All of the closed stations were in the historic center area, with the exception of the stations of Line 2 south of Pino Suárez. These stations were located above the ground. The reason these stations were closed was not due to damage to the Metro proper, but rather because of surface rescue work and clearing of debris.[17]

Fourth stage (1985–1987)

Fourth stage saw the completion of Line 6 from Instituto del Petróleo to its eastern terminal Martín Carrera and Line 7 to the north from Tacuba to El Rosario. Line 9 was the only new line built during this stage. It originally ran from Pantitlán to Centro Médico, and its expansion to Tacubaya was completed on 29 August 1988. For Line 9, a circular deep-bore tunnel and an elevated track were used.

Fifth stage (1988–1994)

For the first time, a service line of the Mexico City Metro ran into the State of Mexico: planned as one of more líneas alimentadoras (feeding lines to be named by letters, instead of numbers), line A was fully operational by its first inauguration on 12 August 1991. It runs from Pantitlán to La Paz, located in the municipality of the same name. This line was built almost entirely above ground, and to reduce the cost of maintenance, steel railway tracks and overhead lines were used instead of pneumatic traction, promoting the name metro férreo (steel-rail metro) as opposed to the previous eight lines that used pneumatic traction.

The draft for Line 8 planned a correspondencia (transfer station) in Zócalo, namely the exact center of the city, but it was canceled due to possible damage to the colonial buildings and the Aztec ruins, so it was replanned and now it runs from Garibaldi, which is still downtown, to Constitución de 1917 in the southeast of the city. The construction of line 8 began in 1988 and was completed in 1994.

With this, the length of the network increased 37.1 kilometres (23.1 mi), adding two lines and 29 more stations, giving the metro network at that point a total of 178.1 kilometres (110.7 mi), 154 stations and 10 lines.

Sixth stage (1994–2000)

Assessment for line B began in late 1993. Line B was intended as a second línea alimentadora for northeastern municipalities in the State of Mexico, but, unlike line A, it used pneumatic traction. Construction of the subterranean track between Buenavista (named after the old Buenavista train station) and Garibaldi began in October 1994. Line B was opened to the public in two stages: from Buenavista to Villa de Aragón on 15 December 1999, and from Villa de Aragón to Ciudad Azteca on 30 November 2000.

Seventh stage (2008–2014)

Plans for a new STC Metro line started in 2008, although previous surveys and assessments were made as early as 2000. Line 12's first service stage was planned for completion in late 2009 with the creation of track connecting Axomulco, a planned new transfer station for Line 8 (between Escuadrón 201 and Atlalilco) to Tláhuac. The second stage, connecting Mixcoac to Tláhuac, was to be completed in 2010.

Construction of Line 12 started in 2008, assuring it would be opened by 2011. Nevertheless, completion was delayed until 2012. Free test rides were offered to the public in some stations, and the line was fully operational on 30 October 2012. With minor changes, Line 12 runs from Mixcoac to Tláhuac, serving southern Mexico City for the first time. At 24.31 kilometres (15.11 mi) long, it is the longest line in the system.

Line 12 differs from previous lines in several aspects: no hawkers are allowed, either inside the train or inside the stations; it is the first numbered line to use steel railway tracks; one must have a Tarjeta DF smart card to access any station since Metro tickets are no longer accepted.

In the book Los hombres del Metro, the original planning of Line 12 is described; although it was to begin at Mixcoac as it does today, Atlalilco and Constitución de 1917 stations of Line 8 were to be part of Line 12. The same map shows that Line 8 would have reached the Villa Coapa area and that it would not have had a terminal at Garibaldi, but at Indios Verdes, linking with Line 3. In addition, the book shows that Line 7 would have terminated at San Jerónimo. None of these plans have been confirmed by the Mexico City government.

In 2015, mayor Miguel Ángel Mancera announced the construction of two more stations and a terminal for Line 12: Valentín Campa,[18] Álvaro Obregón and Observatorio, both west of Mixcoac. With this, Line 12 is to be connected to Line 1, providing new metro access to the Observatorio zone, which will become the terminal for the intercity train between Mexico City and Toluca.[19][20]

Archaeological finds

The metro system's construction has resulted in more than 20 thousand archeological finds, from various time periods in the history of the indigenous people.[21] The excavations needed to make way for the rails gave opportunities to find artifacts from different periods of the region's inhabitants, in areas that are now densely urbanized. Objects and small structures were found, with origins spanning from prehistoric times to the 20th century. Some examples of artifacts preserved by the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México (INAH)) are: parts of pyramids (like an altar to the Mexica god Ehecatl), a sculpture of the goddess Coatlicue, and remains of a mammoth.[22] The altar to Ehécatl is now in Pino Suárez station, between lines 1 and 2, and is called by the INAH the smallest archeological site in Mexico. The metro has led to a large quantity of archeological finds, and has also let archaeologists understand more about the pattern of ancient civilizations in the Mexican capital by analyzing its underground from various time periods.

Architecture

Distinguished architects were hired to design and construct the stations on the first metro line, such as Enrique del Moral, Félix Candela, Salvador Ortega and Luis Barragán. Examples of Candela's work can be seen in San Lázaro, Candelaria, and Merced stations on Line 1.

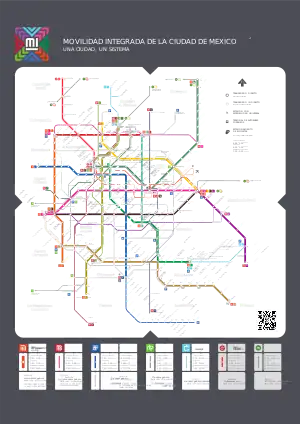

Network map

Lines, stations, names, colors, and logos

.png.webp)

Each line offers one service only, and to each line, a number (letter if feeding line) and color are assigned. Every assigned color is present on square-shaped station logos, system maps and street signs, and neither colors nor numbers have been changed. Line B is the only exception to the color assignment, as green (upper half) and grey (lower half) are used, producing thus bicolor logos and signs. Gray only may be used to avoid confusion with line 8, which uses a similar green.

The names of metro stations are often historical in nature, highlighting people, places, and events in Mexican history. There are stations commemorating aspects of the Mexican Revolution and the revolutionary era. When it opened in 1969 with line 1 (the "Pink Line"), two stations alluded to the Revolution. Most directly referencing the Revolution was Pino Suárez, named after Francisco I. Madero's vice president, who was murdered with him in February 1913. The other was Balderas, whose icon is a cannon, alluding to the Ciudadela armory where the coup against Madero was launched. In 1970, Revolución opened, with the station at the Monument to the Revolution. As the Metro expanded, further stations with names from the revolutionary era opened. In 1980, two popular heroes of the Revolution were honored, with Zapata explicitly commemorating the peasant revolutionary from Morelos. A sideways commemoration was División del Norte, named after the Army that Pancho Villa commanded until its demise in the Battle of Celaya in 1915.

The year 1987 saw the opening of the Lázaro Cárdenas station. In 1988, Aquiles Sedán honors the first martyr of the Revolution. In 1994, Constitución de 1917 opened, as did Garibaldi, named after the grandson of Italian fighter for independence, Giuseppe Garibaldi. The grandson had been a participant in the Mexican Revolution. In 1999, the radical anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón was honored with the station of the same name. Also opening in 1999 was Romero Rubio, named after the leader of Porfirio Díaz's Científicos, whose daughter, Carmen Romero Rubio, became Díaz's second wife.[23] In 2012, a new Metro line opened with an Hospital 20 de Noviembre stop, a hospital named after the date that Francisco I. Madero in his 1910 Plan de San Luis Potosí called for rebellion against Díaz. There are no Metro stops named for Madero, Carranza, Obregón, or Calles, and only an oblique reference to Villa in Metro División del Norte.

Each station is identified by a minimalist logo, first designed by Lance Wyman, who had also designed the logo for the 1968 Mexico Olympics.[24] Logos are generally related to the name of the station or the area around it. At the time of Line 1's opening, Mexico's illiteracy rate was high.[25][26] As of 1960, 38% of Mexicans over the age of five were illiterate and only 5.6% of Mexicans had completed elementary school.[27] Since one-third of the Mexican population could not read or write and most of the rest had not completed high school, it was thought that patrons would find it easier to guide themselves with a system based on colors and visual signs.

The logos are not assigned at random; rather, they are designated by considering the surrounding areas, such as:

- The reference places that are located around the stations (e.g., the logo for Salto del Agua fountain depicts a fountain).

- The topology of an area (e.g., Coyoacán—in Nahuatl "place of coyotes"—depicts a coyote).

- The history of the place (e.g., Juárez, named after President Benito Juárez, depicts his silhouette).

The logos' background colors reflect those of the line the station serves. Stations serving two or more lines show the respective colors of each line in diagonal stripes, as in Salto del Agua. This system was adopted for the Guadalajara and Monterrey metros, and for the Mexico City Metrobús. Although logos are no longer necessary due to literacy being now widespread, their usage has remained.

| Line | Northern/Western terminal[3] | Southern/Eastern terminal[3] | Total stations[3] | Passenger track[28] | Inauguration[3] | Ridership (2019)[2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | Observatorio (W) | Pantitlán (E) | 20 | 16.65 kilometres (10.35 mi) | 4 September 1969 | 242,787,412 | |

| Line 2 | Cuatro Caminos (N) | Tasqueña (S) | 24 | 20.71 kilometres (12.87 mi) | 1 August 1970 | 269,149,446 | |

| Line 3 | Indios Verdes (N) | Universidad (S) | 21 | 21.28 kilometres (13.22 mi) | 20 November 1970 | 222,368,257 | |

| Line 4 | Martín Carrera (N) | Santa Anita (S) | 10 | 9.36 kilometres (5.82 mi) | 29 August 1981 | 29,013,032 | |

| Line 5 | Politécnico (N) | Pantitlán (S) | 13 | 14.44 kilometres (8.97 mi) | 19 December 1981 | 86,512,999 | |

| Line 6 | El Rosario (W) | Martín Carrera (E) | 11 | 11.43 kilometres (7.10 mi) | 21 December 1983 | 49,945,822 | |

| Line 7 | El Rosario (N) | Barranca del Muerto (S) | 14 | 17.01 kilometres (10.57 mi) | 20 December 1984 | 108,152,051 | |

| Line 8 | Garibaldi / Lagunilla (N) | Constitución de 1917 (S) | 19 | 17.68 kilometres (10.99 mi) | 20 July 1994 | 133,620,679 | |

| Line 9 | Tacubaya (W) | Pantitlán (E) | 12 | 13.03 kilometres (8.10 mi) | 26 August 1987 | 113,765,528 | |

| Line A | Pantitlán (W) | La Paz (E) | 10 | 14.89 kilometres (9.25 mi) | 12 August 1991 | 112,288,064 | |

| Line B | Ciudad Azteca (N) | Buenavista (S) | 21 | 20.28 kilometres (12.60 mi) | 15 December 1999 | 152,545,958 | |

| Line 12 | Mixcoac (W)[9] | Tláhuac (E)[9] | 20[9] | 24.11 kilometres (14.98 mi) | 30 October 2012[9] | 134,900,367 | |

Under construction:

| Line | Northern/Western terminal | Southern/Eastern terminal | Total stations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 12 western extension | Observatorio (W) | Mixcoac (E) | 3 | |

Transfers to other systems

| Year | Ridership | % Change |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 1,396,408,190 | - |

| 2003 | 1,375,089,433 | -1.55% |

| 2004 | 1,441,659,626 | +4.84% |

| 2005 | 1,440,744,414 | -0.06% |

| 2006 | 1,416,995,974 | -1.65% |

| 2007 | 1,352,408,424 | -4.56% |

| 2008 | 1,460,144,568 | +7.38% |

| 2009 | 1,414,907,798 | -3.20% |

| 2010 | 1,530,352,732 | +8.16% |

| 2011 | 1,594,903,897 | +4.22% |

| 2012 | 1,608,865,177 | +0.88% |

| 2013 | 1,684,936,618 | +4.73% |

| 2014 | 1,614,333,594 | -4.19% |

| Sources:[29][30][31][32][33][34][35] | ||

The Mexico City Metro offers in and out-street transfers to four major rapid transit systems: the Mexico City Metrobús and State of Mexico Mexibús bus rapid transit systems, the Mexico City light rail system and the Ferrocarril Suburbano (FSZMVM) commuter rail. None of these are part of the Sistema de Transporte Colectivo network and an extra fare must be paid for access.

Metrobús line 1 was inaugurated in 2005. According to the 1985 STC Metro Master Plan, Metrobús Line 1 roughly follows the route planned for STC Metro Line 15 by 2010, which was never built. Every transfer is out-of-station, but the same smart card may be used for payment. All five lines (Line 5 to be built during 2013) offer a connection to at least one STC Metro station. STC Metro stations that connect to Metrobús lines include Indios Verdes, La Raza, Chilpancingo, Balderas, Etiopía / Plaza de la Transparencia, Insurgentes Sur and others.

The sole light rail line running from Tasqueña to Xochimilco is operated by the Servicio de Transportes Eléctricos and is better known as Tren Ligero. Line 2 terminal Tasqueña offers an in-station transfer, but an extra ticket must be purchased.

In 2008, the Ferrocarril Suburbano commuter rail, commonly known as Suburbano, was inaugurated with a sole line running from Cuatitlán to Buenavista as of 2013. STC Metro offers two in-station transfers: Line B terminal Buenavista to the Suburbano terminal of the same name, and Line 6 station Ferrería / Arena Ciudad de México into Suburbano station Fortuna. An extra fare must be paid, and a Ferrocarril Suburbano smart card is required for access.

Another commuter rail, Tren Interurbano de Pasajeros Toluca-Valle de México is estimated to be completed in 2023. This line will connect Observatorio station in Mexico City with Toluca.

Fares and pay systems

A single ticket, currently MXN $5.00, allows a rider one trip anywhere within the system with unlimited transfers. A discounted rate of MXN $3.00 is available upon application for women head of households, the unemployed, and students with scarce resources.[36] Mexico City Metro offers free service to the elderly, the physically impaired, and children under the age of 5 (accompanied by an adult). Tickets can be purchased at booths. They are made of paper and have a magnetic strip on them, and are recycled upon being inserted into a turnstile.

Until 2009, a STC Metro ticket cost MXN $2.00 (€ 0.10, or US$ 0.15 in 2009); one purchased ticket allowed unlimited distance travel and transfer at any given time for one day, making the Mexico City Metro one of the cheapest rail systems in the world.[37] Only line A's transfer in Pantitlán required a second payment before 13 December 2013. In January 2010, the price rose to MXN $3.00 (€ 0.15, or US$ 0.24), a fare that remained until 13 December 2013; a 2009 survey showed that 93% of citizens approved of the increase, while some said they would be willing to pay even more if needed.[38]

STC Metro rechargeable cards were first available for an initial cost of MXN $10.00. The card would be recharged at the ticket counter in any station (or at machines in some Metro stations) to a maximum of MXN $120.00 (around € 6.44, or US$ 7.05 in 2015) for 24 trips.[39]

In an attempt to modernize public transport, in October 2012, the Mexico City government implemented the use of a prepaid fare card, or stored-value card, called Tarjeta DF (Tarjeta del Distrito Federal, literally Federal District Card) as a payment method for STC Metro, Metrobús and the city's trolleybus and light rail systems, though they are all managed by different organizations.[40] Servicio de Transportes Eléctricos manages both the Xochimilco Light Rail line and the city's trolleybus system. Previous fare cards that were valid only on STC Metro or Metrobús remained valid for the system for which they were acquired.[41]

Rolling stock

As of April 2012, 14 types of standard gauge rolling stock totalling a number of 355 trains running in 6-or 9-car formation are currently in use on the Mexico City Metro. Most of the stock is rapid transit type, with the exception of the Line A stock, which is light metro. Four manufacturers have provided rolling stock for the Mexico City Metro, namely the French Alstom (MP-68, NM-73, NM-79), Canadian Bombardier (FM-95A and NM-02), Spanish CAF (NM-02, FE-07, FE-10 and NM-16 and Mexican Concarril (NM-83 and FM-86) (now Bombardier Transportation Mexico, in some train types with the help of Alstom and/or Bombardier).

The maximum design speed limit is 80 km/h (50 mph) (average speed 35.5 km/h or 22.1 mph) for rubber-tired rolling stock and 100 km/h (62 mph) (average speed 42.5 km/h or 26.4 mph) for steel-wheeled rolling stock. Forced-air ventilation is employed and the top portion of windows can be opened so that passenger comfort is enhanced by the combination of these two types of ventilation. Like the rolling stock used in the Paris Métro and the Montreal Metro, the numbering of the Mexico City Metro's rolling stock are specified by year of design (not year of first use).

In chronological order, the types of rubber-tired rolling stock are: MP-68, NM-73A, NM-73B, NM-73C, NM-79, MP-82, NC-82, NM-83A, NM-83B, NE-92, NM-02 and NM-16; and the types of steel-wheeled rolling stock are: FM-86, FM-95A, FE-07, and FE-10.

From May 2024, Line 1 will receive 30 new rubber-tired trains manufactured by CRRC Zhuzhou Locomotive in China, replacing earlier rolling stock. This is in line with ongoing upgrading works for Line 1, including the installation of CBTC.[42][43]

Major incidents

On 20 October 1975, two trains crashed in Viaducto station while both were going towards Tasqueña station. The first was stopped picking up passengers when it was hit by another train that did not stop in time. According to official reports, from 31 to 39 people died, and between 71 and 119 were injured. After the crash, automatic signals were incorporated to all lines.[44]

On 18 September 2009, a man was vandalizing the walls of Balderas station with a marker before being confronted by a police officer. He took out a gun and killed the officer and a construction worker who tried to disarm him, and injured 5 others.[44]

On 4 May 2015, two trains heading towards Politécnico station on Line 5 crashed in Oceanía station. The first was leaving to Aragón station and was requested to stop and wait, while the second did not deactivate the autopilot and crashed into it at the end of the platform. 12 people were injured.[45]

On 10 March 2020, two trains heading towards Observatorio station on Line 1 crashed in Tacubaya station. The first train was parked at the platform when it was hit by another train that was coming in reverse. 1 person died and 41 were injured, all inside the second train, as people in the parked train had been evacuated moments before the crash.[46][47]

On 9 January 2021, the Central Control Center serving lines 1 to 6 caught fire. During the fire, a female police officer was killed due to a fall in the building. All the stations on those lines temporarily remained closed and provisional transport service was provided by city buses and police vehicles. According to the Metro authorities, the service in lines 4, 5, and 6 would be normalized in days, while that in lines 1, 2, and 3 in several months.[48]

On 3 May 2021, a train was traveling on Line 12 between the Olivos and Tezonco stations when a girder supporting the overpass on which the train was traveling collapsed, killing 26 and injuring more than 70.[49] Service on Line 12 was later suspended, while STC warned residents to avoid the site of the collapse.[50][51][52]

On 7 January 2023 at 09:16 local time, two trains collided between Potrero and La Raza stations on Line 3, killing one and injuring 57.[53][54] In addition to other minor events,[55][56][57] city officials said that this accident was a result of sabotage to the Fourth Transformation platform to affect the image of Claudia Sheinbaum, then mayor of the city and a potential candidate on the 2024 Mexican general election.[58][59]

See also

- List of Latin American rail transit systems by ridership

- List of North American rapid transit systems by ridership

- List of metro systems

- List of Mexico City Metro stations

- List of Mexico City Metro lines

- Metro systems by annual passenger rides

- Metrobús

- Xochimilco Light Rail

- Rubber-tired metro

- Servicio de Transportes Eléctricos

- Transport in Mexico City

- Tren Suburbano

References

- "Cifras de operación" [Operations figures] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de México. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Afluencia de estación por línea 2019" (in Spanish). Metro CDMX. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Inauguraciones y Ampliaciones en Orden Cronológico Hasta 2000" [Inaugurations and Extensions in Chronological Order Until 2000] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de Mexico. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Parque Vehicular" [Vehicle Fleet] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de México. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "LONGITUDES DE LAS LINEAS" [Operations figures] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de México. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Luis M. Castañeda, Spectacular Mexico: Design, Propaganda, and the 1968 Olympics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2014, p. 243

- Coordinación de Desarrollo Tecnológico. "Clasificación de las estaciones por su uso y por su tipo" (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de México. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017.

- "Sabías Que... Linea 12" [Did You Know... Line 12] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de Mexico. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- "Linea 12" [Line 12] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de Mexico. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Metro Chabacano by Javier Álvarez". Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2016 – via www.youtube.com.

- Castañeda, Spectacular Mexico pp. 241-42.

- Castañeda, Spectacular Mexico citing Monsiváis, "El metro: Viaje hacia el fin del apretujón," in Carlos Monsiváis, Los rituales del caos. Mexico City: Ediciones Era 1995, 109-10.

- "29/04/1967 - Edición Matutina". Diario Oficial de la Federacion (in Spanish). 29 April 1967. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- The Mexico City Metro Modern Railways issue 432 September 1984 pages 477-480

- "Etapas de construcción de la red del STC Metro" [Stages of construction of the STC Metro network] (in Spanish). Mexico City Metro (STC). Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Suicidios in Tlatelolco:Sismo en Mexico" (in Spanish). Mexico City: La Prensa. 14 September 2005. p. 2.

- Michoacan (in Maroc) Mexico City. 1999. pp. 8–28.

- Cruz, Alejandro (15 February 2013). "Ponen Valentín Campa a tren del Metro; nueva estación también llevará su nombre". La Jornada. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Anuncia Mancera la próxima ampliación de la Línea 12 del Metro" [Mancera announces the forthcoming extension of Metro Line 12]. El Sol de México (in Spanish). Organización Editorial Mexicana. 14 February 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Robles, Johana (15 February 2013). "Plantean alargar la L-12 del Metro hasta Alta Tensión" [Extension of Metro line 12 to the 'Alta Tensión' area proposed]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Mexico City Subway Dig Yields Aztec Remains and Artifacts - History in the Headlines". HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "Remains of a mammoth uncovered near Mexico City". BBC News. 25 June 2016. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Perhaps enough time had passed since the Revolution and Romero Rubio was just a name with no historical significance to ordinary Mexicans. In 2000, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost the presidential election to the candidate of the National Action Party (PAN).

- Castañeda, Spectacular Mexico, pp. 151-55, 221-28.

- Marianne Ström, Metro-art in the Metro-polis (Paris: ACR Edition, 1994), 210. ACR Edition is the actual name of this book's publisher, not an indicator of a particular edition.

- John Ross, El Monstruo: Dread and Redemption in Mexico City (New York: Nation Books, 2009), 239.

- Francisco Alba, The Population of Mexico: Trends, Issues, and Policies (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1982), 52.

- "Longitudes de las Líneas (KM)" [Line lengths (km)] (in Spanish). Metro de la Ciudad de Mexico. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Sistema de Transporte Colectivo de la Ciudad de México, Metro". Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- "Tarifa Deferenciada de 3 Pesos" [Discounted fare of 3 pesos] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Schwandl, Robert (2007). "UrbanRail.Net > Central America > Mexico > Ciudad de Mexico Metro". Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- "Aprueban usuarios incremento a la tarifa del Metro (Spanish)". Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "STC: Tarjeta Recargable (Spanish)". Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- "Arranca el uso de la TarjetaDF para Metro, Metrobús y Trolebús" [Use of the TarjetaDF for Metro, Metrobús and Trolleybus begins]. Excélsior (in Spanish). 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- "STC: Nueva Tarjeta del Distrito Federal (Spanish)". Archived from the original on 26 January 2013.

- "El Metro se renueva: Así serán los nuevos trenes de la Línea 1". 2 May 2022.

- "Cómo serán los trenes nuevos de la Línea 1 del Metro?". 3 May 2022.

- Tiempo Real magazine (18 September 2012). "El Metro de la Ciudad de México, como escenario de eventos trágicos, y muy trágicos" (in Spanish). Sin Embargo. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Valdez, Ilich (12 May 2015). "Error humano causó choque de trenes en Metro Oceanía". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Cruz, Héctor; Ruiz, Kevin (12 March 2020). "Convoy se deslizó hacia atrás 70km/h: investigación". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Subway collision kills one, leaves dozens injured in Mexico City". DW. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- "Fire kills police officer, shuts down 6 lines of Mexico City Metro". Mexico News Daily. 11 January 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- "Mexico City metro overpass collapse kills 23". BBC News. 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- "Sube a 24 la cifra de muertos por el derrumbe del metro de Ciudad de México". SWI swissinfo.ch (in Spanish). 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "Overpass collapse on Mexico City metro kills at least 24". AP NEWS. 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "Cierran toda la Línea 12 del Metro; RTP brindará servicio de apoyo". Chilango (in Spanish). 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "Qué se sabe del choque de trenes en el Metro de CDMX que dejó al menos 1 muerto y casi 60 lesionados". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). 7 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- "Metro realiza las maniobras necesarias para reapertura completa de la línea 3". Forbes México (in Mexican Spanish). 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- "Chicken loose on subway tracks halts service in Mexico City". AP News. 16 May 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- Peralta, Omar (24 January 2023). "Se le cayeron aspas en Metro de CDMX; la acusaron de sabotaje y solo quería arreglar su lavadora". Yahoo (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- Pérez Ángeles, Vianey (16 January 2023). "Sabotaje en Metro Polanco: Cilindro de seguridad desprendido provocó la separación de vagones (VIDEO)". SDP Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- "Choque en Línea 3: Chilangos 'no compran' teoría de Sheinbaum sobre sabotaje". El Financiero (in Spanish). 19 January 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- García, Carina (11 January 2023). "Legisladores morenistas y aliados piden indagar 'sabotaje' en Metro de la CDMX". Expansión (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 June 2023.

Further reading

- Beltrán González, José Antonio. Historia de los nombres de las estaciones del metro. Mexico City 1973.

- Castañeda, Luis. M. Spectacular Mexico: Design, Propaganda, and the 1968 Olympics, chapter 5, "Subterranean Scenographies: Time Travel at the Mexico City Metro". Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2014.

- Davis, Diane E. Urban Leviathan: Mexico City in the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: Temple University Press 1994.

- Derou, Georges. "El metro de ciudad de México visto por los franceses," Presencia 1 (1970).

- "El arte del metro mexicano," Life en Español. 29 September 1969.

- Espinosa Ulloa, Jorge. El metro: Una solución al problema del transporte urbano. Mexico City: Representaciones y Servicios de Ingeniería 1975.

- Giniger, Henry, "Mexico City Subway Runs Deep into the Past: Relics of 600 Years in vast Quantity Are Being Unearthed," New York Times, 16 January 1969, 8.

- Gussinyer, Jordi. "Hallazgos en el metro: Conjunto de adoratorios superpuestos en Pino Suárez," Boletín del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia 36 (June 1969).

- Gómez Mayorga, Mauricio. "Planificación: La ciudad de México y sus transportes," Calli 3 (1960).

- "Mexico City's Subway is for Viewing," Fortune, December 1969.

- Monsiváis, Carlos, "El metro: Viaje hacia el fin del apretujón," in Carlos Monsiváis, Los rituales del caos. Mexico City: Ediciones Era 1995.

- Navarro, Bernardo and Ovidio González, Metro, Metrópoli, México. Xochimilco: UAM,Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, 1989.

- Novo, Salvador, "Crónica" in El metro de México: Primera memoria. Mexico City: Sistema de Transporte Colectivo-Metro 1973.

- Novo, Salvador, New Mexican Grandeur, trans. Noel Lindsay. Mexico City: PEMEX 1967.

- Rodríguez, Antonio. "La solución: El metro o el monorriel?" Siempre! 1 September 1965.

- Valencia Ramírez, Ariel. "Tecnología y cultura en el metro," Presencia 1 (1970).

- Villoro, Juan. "The Metro" in Rubén Gallo, ed. Mexico City Reader, trans. Lorna Scott Fox. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 2004.

- Wise, Sydney Thomas. "Mexico City's Metro--The World's Highest Subway--Quietly Rolls Along," New York Times, 3 August 1969.

- Wyman, Lance, "Subway Signage" in Peter Blake, Subways of the World Examined by the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum 1977.

- Zamora, Adolfo. La cuestión del tránsito en una ciudad que carece de subsuelo adecuado para vía subterráneas o elevadas. Mexico City: XVI Congreso Internacional de Planificación y de la Habitación, August 1939.

External links

Media related to Mexico City subway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mexico City subway at Wikimedia Commons- Mexico City Metro - official website (in Spanish)

- Metro Chabacano, string quartet performance

- 2019 Google Doodle for the Mexico City Subway's 50th anniversary