Slamannan

Slamannan (Scottish Gaelic: Sliabh Mhanainn) is a village in the south of the Falkirk council area in Central Scotland. It is 4.6 miles (7.4 km) south-west of Falkirk, 6.0 miles (9.7 km) east of Cumbernauld and 7.1 miles (11.4 km) north-east of Airdrie.

Slamannan

| |

|---|---|

Centre of Slamannan | |

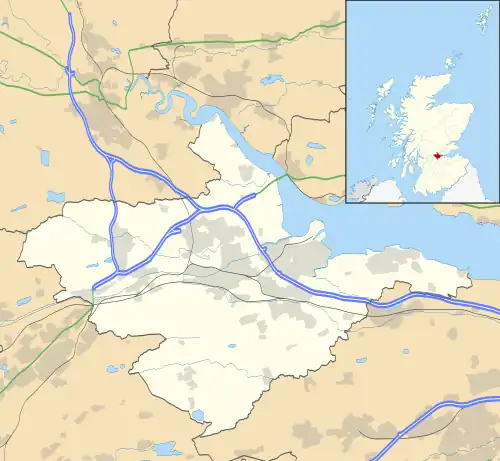

Slamannan Location within the Falkirk council area | |

| Area | 0.19 sq mi (0.49 km2) |

| Population | 1,180 (mid-2020 est.)[1] |

| • Density | 6,211/sq mi (2,398/km2) |

| OS grid reference | NS855731 |

| • Edinburgh | 25.0 mi (40.2 km) E |

| • London | 342 mi (550 km) SSE |

| Civil parish |

|

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | FALKIRK |

| Postcode district | FK1 |

| Dialling code | 01324 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Slamannan is located at the cross of the B803 and B8022 roads, near the banks of the River Avon, close to the border between Falkirk and North Lanarkshire councils. Slamannan had a population of around 1,360 residents.[2] In 1755 the population was recorded as 1209.[3] Fifty years later the population was around the 1000 in the Parish of Slamanan[4] (although elsewhere in the same volume the usual spelling is used). The 19th-century parish church can accommodate upwards of 700 people.

History and Toponymy

The name relates to the Manaw Gododdin tribe about whom little is known.[7] The name possibly means hill-face of Manan.[8] The church at Slamannan used to be named after St Laurence.[9] There is also a well which bears his name.[10] It is recorded that in 1470 James II gave a charter to Lord Livingstone for the lands of Slamannan.[11] James IV paid a guide sixpence to help him cross the moor of Slamannan in August 1491 during an excursion in the Bathgate area from Linlithgow Palace.[12]

The area was once well known for steam coal which was worked at Longriggend.[13] Farming was also practiced on about 40 farms in the parish.[14] Several other old maps show Slamannan with various spellings including maps by John Grassom,[15] John Ainslie[16] and John Thomson.[17] Only the Ordnance Survey Map shows the Culloch Burn.[18] Gas lighting was set up in 1855.[19] By 1882 the population had grown to 1644 with over 200 people in school.[20] Newspaper articles mentioning Slamannan are available from the 18th century.[21]

Notable residents

Former Cabinet Minister Viscount Horne was born in Slamannan in 1871, the son of the village's Church of Scotland minister. After study at the University of Glasgow, he became a successful QC and was elected to represent Glasgow Hillhead in Parliament, and served as Minister of Labour, President of the Board of Trade and Chancellor of the Exchequer under Lloyd George after the First World War. He was ennobled in 1937 as Viscount Horne of Slamannan.

Other distinguished sons of Slamannan manse include John Cameron and his brothers Hugh, Sandy and Kenneth, all of whom won national titles in athletics in the 1960s and 70s (John and Kenneth as runners, and Hugh and Sandy in the heavy field events). All of them later went on to become doctors. Their father, Alexander Cameron was an interesting man in his own right, having been a miner who went up to Glasgow University from the West Central coalfields in the depths of the Depression to study divinity. After serving as an army padre throughout the War, he went back to the coalfields in 1946 as a Church of Scotland minister. He was also the village's Labour county councillor and convener of Stirlingshire Education Committee for twenty years until his death from black lung in 1968.

Early twentieth-century Everton footballer, Alex "Sandy" Young was born in Slamannan, and spent his youth years playing for Slamannan Juniors. He remains the all-time fourth-highest scorer for Everton, and scored the only goal at the 1906 FA Cup Final. Another footballer, Andrew Smith, also hailed from the village. He played for numerous clubs in Scotland and England including East Stirlingshire, West Bromwich Albion, Newton Heath (later renamed Manchester United) and Bristol Rovers.[22][23]

Lance Corporal Samuel Frickleton, was born in Slamannan, in 1891, the son of Samuel and Elizabeth Frickleton.[24] The family emigrated to New Zealand to take advantage of the plentiful jobs on offer in the coal mining industry, and the following year saw the outbreak of the First World War. Corporal Frickleton was awarded the military's highest honour for his actions in the Battle of Messines. His bravery was so outstanding that his commanding officer claimed he could have won the Victoria Cross "twice over".

Another notable military man from the village who was highly decorated was Sgt Observer James Bryce, who was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal for his exploits in the RAF in WW2.

See also

.jpg.webp)

References

- "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "Estimated population of localities by broad age groups, mid-2012" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Macnair, James (1791). The statistical account of Scotland. Drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different parishes. [electronic resource] (Vol XIV no IV ed.). Edinburgh: William Creech. p. 84. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Davidson, Alexander (1841). The new statistical account of Scotland. [electronic resource]. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 273–280. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Blaeu, Joan. "Sterlinensis praefectura, Sterlin-Shyr". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Pont, Timothy. "The East Central Lowlands (Stirling, Falkirk & Kilsyth) - Pont 32". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Rhys, John, Sir (1904). Celtic Britain (3rd ed.). London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 155. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Johnston, James Brown (1904). The place names of Stirlingshire. Stirling: R.S. Shearer. p. 59. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Johnston, James Brown (1904). The place names of Stirlingshire. Stirling: R.S. Shearer. p. 18. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Slamannan, Main Street, Slamannan Parish Church And St Laurence's Well". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Macnair, James (1791). The statistical account of Scotland. Drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different parishes. [electronic resource] (Vol XIV no IV ed.). Edinburgh: William Creech. pp. 78–87. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 180.

- Dron, Robert W. (1902). The Coal-fields of Scotland. London: Blackie & Son. p. 157. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Nimmo, William (1880). The history of Stirlingshire; revised, enlarged and brought to the present time (Vol II, 3rd ed.). Glasgow: Thomas D. Morison. p. 277. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "To the Noblemen and Gentlemen of the County of Stirling..." NLS. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Ainslie's Map of the Southern Part of Scotland". NLS. Edinburgh: Macreadie Skelly & Co., 1821. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "John Thomson's Atlas of Scotland, 1832". NLS. Edinburgh : J. Thomson & Co., 1823. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "OS 25 inch map 1892-1949, with Bing opacity slider". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Bailey, Geoff. "Slamannan". Falkirk Local History Society. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Wilson, John Marius (1882). The gazetteer of Scotland. Edinburgh: W. & A.K. Johnston. p. 414. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Your results for: slamannan". British Newspaper Archive. Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- Joyce, Michael (2004). Football League Players' Records 1888–1939. Nottingham: SoccerData. p. 241. ISBN 1899468676.

- Byrne, Stephen; Jay, Mike (2003). Bristol Rovers Football Club: The Definitive History 1883–2003. Stroud: Tempus. p. 492. ISBN 0-7524-2717-2.

- Barber, Stuart (9 June 2017). "Village and VIPs remember World War One hero Samuel Frickleton VC". The Falkirk Herald. Retrieved 3 February 2018.