South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of 984,321 square kilometres (380,048 sq mi),[5] it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, and second smallest state by population. It has a total of 1.8 million people.[2] Its population is the second most highly centralised in Australia, after Western Australia, with more than 77 percent of South Australians living in the capital Adelaide, or its environs. Other population centres in the state are relatively small; Mount Gambier, the second-largest centre, has a population of 33,233.

South Australia | |

|---|---|

Nickname(s):

| |

| Country | Australia |

| Before federation | Province of South Australia |

| Settlement | 15 August 1834 |

| Declared as Province | 19 February 1836 |

| Responsible government | 22 April 1857 |

| Federation | 1 January 1901 |

| Capital and largest city | Adelaide |

| Administration | 74 local government areas |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Governor | Frances Adamson |

• Premier | Peter Malinauskas (Labor) |

| Legislature | Parliament of South Australia |

| Legislative Council | |

| House of Assembly | |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of South Australia |

| Parliament of Australia | |

• Senate | 12 senators (of 76) |

| 10 seats (of 151) | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,044,353 km2 (403,227 sq mi) (4th) |

• Land | 984,321 km2 (380,048 sq mi) |

• Water | 60,032 km2 (23,178 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,435 m (4,708 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −16 m (−52 ft) |

| Population | |

• March 2022 estimate | 1,815,485[2] (5th) |

• Density | 1.7/km2 (4.4/sq mi) (6th) |

| GSP | 2020 estimate |

• Total | AU$108.334 billion[3] (5th) |

• Per capita | AU$61,582 (7th) |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 7th |

| Time zone |

|

| UTC+10:30 (ACDT) | |

| Postal abbreviation | SA |

| ISO 3166 code | AU–SA |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Piping shrike (Australian magpie) |

| Fish | Leafy seadragon (Phycodurus eques) |

| Flower | Sturt's Desert Pea (Swainsona formosa) |

| Mammal | Southern hairy-nosed wombat (Lasiorhinus latifrons) |

| Colour(s) | Red, blue, and gold |

| Fossil | Spriggina floundersi |

| Mineral | Bornite, Opal as Gem |

| Website | sa |

South Australia shares borders with all of the other mainland states, as well as the Northern Territory; it is bordered to the west by Western Australia, to the north by the Northern Territory, to the north-east by Queensland, to the east by New South Wales, to the south-east by Victoria, and to the south by the Great Australian Bight.[6] The state comprises less than 8 percent of the Australian population and ranks fifth in population among the six states and two territories. The majority of its people reside in greater Metropolitan Adelaide. Most of the remainder are settled in fertile areas along the south-eastern coast and River Murray. The state's colonial origins are unique in Australia as a freely settled, planned British province,[7] rather than as a convict settlement. Colonial government commenced on 28 December 1836, when the members of the council were sworn in near the Old Gum Tree.[8]

As with the rest of the continent, the region has a long history of human occupation by numerous tribes and languages. The South Australian Company established a temporary settlement at Kingscote, Kangaroo Island, on 26 July 1836, five months before Adelaide was founded.[9] The guiding principle behind settlement was that of systematic colonisation, a theory espoused by Edward Gibbon Wakefield that was later employed by the New Zealand Company.[10] The goal was to establish the province as a centre of civilisation for free immigrants, promising civil liberties and religious tolerance. Although its history has been marked by periods of economic hardship, South Australia has remained politically innovative and culturally vibrant. Today, it is known for its fine wine and numerous cultural festivals. The state's economy is dominated by the agricultural, manufacturing and mining industries.

History

Evidence of human activity in South Australia dates back as far as 20,000 years, with flint mining activity and rock art in the Koonalda Cave on the Nullarbor Plain. In addition wooden spears and tools were made in an area now covered in peat bog in the South East. Kangaroo Island was inhabited long before the island was cut off by rising sea levels.[11] According to mitochondrial DNA research, Aboriginal people reached Eyre Peninsula 49,000-45,000 years ago from both the east (clockwise, along the coast, from northern Australia) and the west (anti-clockwise).[12]: 189

The first recorded European sighting of the South Australian coast was in 1627 when the Dutch ship the Gulden Zeepaert, captained by François Thijssen, examined and mapped a section of the coastline as far east as the Nuyts Archipelago. Thijssen named the whole of the country eastward of the Leeuwin "Nuyts Land", after a distinguished passenger on board; the Hon. Pieter Nuyts, one of the Councillors of India.[13]

The coastline of South Australia was first mapped by Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin in 1802, excepting the inlet later named the Port Adelaide River which was first discovered in 1831 by Captain Collet Barker and later accurately charted in 1836–37 by Colonel William Light, leader of the South Australian Colonization Commissioners' 'First Expedition' and first Surveyor-General of South Australia.

The land which now forms the state of South Australia was claimed for Britain in 1788 as part of the colony of New South Wales. Although the new colony included almost two-thirds of the continent, early settlements were all on the eastern coast and only a few intrepid explorers ventured this far west. It took more than forty years before any serious proposal to establish settlements in the south-western portion of New South Wales were put forward.

On 15 August 1834, the British Parliament passed the South Australia Act 1834 (Foundation Act), which empowered His Majesty to erect and establish a province or provinces in southern Australia. The act stated that the land between 132° and 141° east longitude and from 26° south latitude to the southern ocean would be allotted to the colony, and it would be convict-free.[14]

In contrast to the rest of Australia, terra nullius did not apply to the new province. The Letters Patent,[15] which used the enabling provisions of the South Australia Act 1834 to fix the boundaries of the Province of South Australia, provided that "nothing in those our Letters Patent shall affect or be construed to affect the rights of any Aboriginal Natives of the said Province to the actual occupation and enjoyment in their own Persons or in the Persons of their Descendants of any Lands therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such Natives."[15] Although the patent guaranteed land rights under force of law for the indigenous inhabitants, it was ignored by the South Australian Company authorities and squatters.[16] Despite strong reference to the rights of the native population in the initial proclamation by the Governor, there were many conflicts and deaths in the Australian Frontier Wars in South Australia.

Survey was required before settlement of the province, and the Colonization Commissioners for South Australia appointed William Light as the leader of its 'First Expedition', tasked with examining 1500 miles of the South Australian coastline and selecting the best site for the capital, and with then planning and surveying the site of the city into one-acre Town Sections and its surrounds into 134-acre Country Sections.

Eager to commence the establishment of their whale and seal fisheries, the South Australian Company sought, and obtained, the Commissioners' permission to send Company ships to South Australia, in advance of the surveys and ahead of the Commissioners' colonists.

The company's settlement of seven vessels and 636 people was temporarily made at Kingscote on Kangaroo Island, until the official site of the capital was selected by William Light, where the City of Adelaide is currently located. The first immigrants arrived at Holdfast Bay (near the present day Glenelg) in November 1836.

The commencement of colonial government was proclaimed on 28 December 1836, now known as Proclamation Day.

South Australia is the only Australian state to have never received British convicts. Another free settlement, Swan River colony was established in 1829 but Western Australia later sought convict labour, and in 1849 Western Australia was formally constituted as a penal colony. Although South Australia was constituted such that convicts could never be transported to the Province, some emancipated or escaped convicts or expirees made their own way there, both prior to 1836, or later, and may have constituted 1–2% of the early population.[17]

The plan for the province was that it would be an experiment in reform, addressing the problems perceived in British society. There was to be religious freedom and no established religion. Sales of land to colonists created an Emigration Fund to pay the costs of transferring a poor young labouring population to South Australia. In early 1838 the colonists became concerned after it was reported that convicts who had escaped from the eastern states may make their way to South Australia. The South Australia Police was formed in April 1838 to protect the community and enforce government regulations. Their principal role was to run the first temporary gaol, a two-room hut.[18]

The current flag of South Australia was adopted on 13 January 1904, and is a British blue ensign defaced with the state badge. The badge is described as a piping shrike with wings outstretched on a yellow disc. The state badge is believed to have been designed by Robert Craig of Adelaide's School of Design.

Geography

The terrain consists largely of arid and semi-arid rangelands, with several low mountain ranges. The most important (but not tallest) is the Mount Lofty-Flinders Ranges system, which extends north about 800 kilometres (500 mi) from Cape Jervis to the northern end of Lake Torrens. The highest point in the state is not in those ranges; Mount Woodroffe (1,435 metres (4,708 ft)) is in the Musgrave Ranges in the extreme northwest of the state.[19]

The south-western portion of the state consists of the sparsely inhabited Nullarbor Plain, fronted by the cliffs of the Great Australian Bight. Features of the coast include Spencer Gulf and the Eyre and Yorke Peninsulas that surround it. The Temperate Grassland of South Australia is situated to the east of Gulf St Vincent.

The principal industries and exports of South Australia are wheat, wine and wool.[21] More than half of Australia's wines are produced in the South Australian wine regions which principally include Barossa Valley, Clare Valley, McLaren Vale, Coonawarra, the Riverland and the Adelaide Hills. See South Australian wine.

South Australian boundaries

South Australia has boundaries with every other Australian mainland state and territory except the Australian Capital Territory and the Jervis Bay Territory. The Western Australia border has a history involving the South Australian government astronomer, G.F. Dodwell, and the Western Australian Government Astronomer, H.B. Curlewis, marking the border on the ground in the 1920s.

In 1863, that part of New South Wales to the north of South Australia was annexed to South Australia, by letters patent, as the "Northern Territory of South Australia", which became shortened to the Northern Territory on 6 July 1863.[22] The Northern Territory was handed to the federal government in 1911 and became a separate territory.

According to Australian maps, South Australia's south coast is flanked by the Southern Ocean, but official international consensus defines the Southern Ocean as extending north from the pole only to 60°S or 55°S, at least 17 degrees of latitude further south than the most southern point of South Australia. Thus the south coast is officially adjacent to the south-most portion of the Indian Ocean. See Southern Ocean: Existence and definitions.

Arid land in the Flinders Ranges

Arid land in the Flinders Ranges The rugged coastline of Second Valley, located on the Fleurieu Peninsula

The rugged coastline of Second Valley, located on the Fleurieu Peninsula

Climate

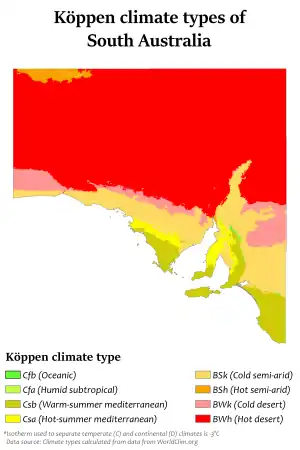

The southern part of the state has a Mediterranean climate, while the rest of the state has either an arid or semi-arid climate.[23] South Australia's main temperature range is 29 °C (84 °F) in January and 15 °C (59 °F) in July. The highest maximum temperature ever recorded was 50.7 °C (123.3 °F) at Oodnadatta on 2 January 1960, which is the highest official temperature recorded in Australia. The lowest minimum temperature was −8.2 °C (17.2 °F) at Yongala on 20 July 1976.[24] The region's overall dry weather is owed to the Australian High on the Great Australian Bight.

| Climate data for South Australia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 50.7 (123.3) |

48.2 (118.8) |

46.5 (115.7) |

42.1 (107.8) |

36.5 (97.7) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

41.5 (106.7) |

45.4 (113.7) |

47.9 (118.2) |

49.9 (121.8) |

50.7 (123.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[25] | |||||||||||||

Economy

As of 2016, South Australia had 746,105 people employed out of a total workforce of 806,593, giving an unemployment rate of 7.5%. South Australia's largest employment sector is health care and social assistance, making up 14.8% of the state's total employment, followed by retail (10.7%), education and training (8.6%), manufacturing (8%), and construction (7.6%).[26] South Australia's economy relies on exports more than any other state in Australia.[27]

South Australia's credit rating was upgraded to AAA by Standard & Poor's in September 2004 and to AAA by Moody's in November 2004, the highest credit ratings achievable by any company or sovereign. The state had previously lost these ratings in the State Bank collapse. However, in 2012 Standard & Poor's downgraded the state's credit rating to AA+ due to declining revenues, new spending initiatives and a weaker than expected budgetary outlook.[28]

South Australia receives the least amount of federal funding for its local road network of all states on a per capita and a per kilometre basis.[29]

.jpeg.webp)

During 2019-20: South Australia's gross state product (GSP) fell 1.4% in chain volume (real) terms (nationally, gross domestic product (GDP) fell 0.3%).[30] South Australia came out of the COVID-19 recession better than the other Australian states, with the economy growing by 3.9% in the 2020–21 financial year. This was the first time since the Australian Bureau of Statistics began collecting data in 1990 that South Australia had outperformed the other states. The recovery was driven in part by growth in the agricultural sector, which increased its production by almost 24% thanks to the end of a drought.[31]

Cereals, legumes and oilseeds

Wheat, barley, oats, rye, peas, beans, chickpeas, lentils and canola are grown in South Australia.[32]

Fruit and vegetables

Apples, pears, cherries and strawberries are grown in the Adelaide Hills.[33] Tomatoes, capsicums, cucumbers, brassicas, lettuce and carrots are grown on the Northern Adelaide Plains at Virginia.[33] Almonds, citrus and stone fruit are grown in the Riverland.[33] Potatoes, onions and carrots are grown in the Murray Mallee region.[33] Potatoes are grown on Kangaroo Island.[33]

Viticulture

South Australia produces more than half of all Australian wine, including almost 80% of Australia's premium wines.[34]

Energy

South Australia has the lead over other Australian states for its commercialisation and commitment to renewable energy. It is now the leading producer of wind power in Australia.[35] Renewable energy is a growing source of electricity in South Australia, and there is potential for growth from this particular industry of the state's economy. The Hornsdale Power Reserve is a bank of grid-connected batteries adjacent to the Hornsdale Wind Farm in South Australia's Mid-North region. At the time of construction in late 2017, it was billed as the largest lithium-ion battery in the world.[36]

Mining

The Olympic Dam mine near Roxby Downs in northern South Australia is the largest deposit of uranium in the world, possessing more than a third of the world's low-cost recoverable reserves and 70% of Australia's. The mine, owned and operated by BHP, presently accounts for 9% of global uranium production.[37][38] The Olympic Dam mine is also the world's fourth-largest remaining copper deposit, and the world's fifth largest gold deposit.[39] There was a proposal to vastly expand the operations of the mine, making it the largest open-cut mine in the world,[40] but in 2012 the BHP Billiton board decided not to go ahead with it at that time due to then lower commodity prices.[41]

The remote town of Coober Pedy produces more opal than anywhere else in the world. Opal was first discovered near the town in 1915, and the town became the site of an opal rush, enticing immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War II.[42]

Education and research

Higher education and research in Adelaide forms an important part of South Australia's economy. The South Australian Government and educational institutions have attempted to position Adelaide as Australia's education hub and have marketed it as a Learning City.[43] The number of international students studying in Adelaide has increased rapidly in recent years to 30,726 in 2015, of which 1,824 were secondary school students.[44] Foreign institutions have been attracted to set up campuses to increase its attractiveness as an education hub.[45][46] Adelaide is the birthplace of three Nobel laureates, more than any other Australian city: physicist William Lawrence Bragg and pathologists Howard Florey and Robin Warren, all of whom completed secondary and tertiary education at St Peter's College and the University of Adelaide.

Adelaide is home to research institutes, including the Royal Institution of Australia, established in 2009 as a counterpart to the two-hundred-year-old Royal Institution of Great Britain.[47] Most of the research organisations are clustered in the Adelaide metropolitan area:

- The east end of North Terrace: SA Pathology;[48] Hanson Institute;[49] National Wine Centre.

- The west end of North Terrace: South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), located next to the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

- The Waite Research Precinct: SARDI Head Office and Plant Research Centre; AWRI;[50] ACPFG;[51] CSIRO research laboratories.[52] SARDI also has establishments at Glenside[53] and West Beach.[54]

- Edinburgh, South Australia: DSTO; BAE Systems (Australia); Lockheed Martin Australia Electronic Systems.

- Technology Park (Mawson Lakes): BAE Systems; Optus; Raytheon; Topcon; Lockheed Martin Australia Electronic Systems.

- Research Park at Thebarton: businesses involved in materials engineering, biotechnology, environmental services, information technology, industrial design, laser/optics technology, health products, engineering services, radar systems, telecommunications and petroleum services.

- Science Park (adjacent to Flinders University): Playford Capital.

- The Basil Hetzel Institute for Translational Health Research[55] in Woodville the research arm of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Adelaide

- The Joanna Briggs Institute, a global research collaboration for evidence-based healthcare with its headquarters in North Adelaide.

The Mitchell Building and Bonython Hall, University of Adelaide

The Mitchell Building and Bonython Hall, University of Adelaide The Hawke Building, part of the UniSA, City West Campus

The Hawke Building, part of the UniSA, City West Campus Flinders University buildings from the campus hills

Flinders University buildings from the campus hills Torrens University

Torrens University

Government

South Australia is a constitutional monarchy with King Charles III as sovereign, and the Governor of South Australia as his representative.[56] It is a state of the Commonwealth of Australia. The bicameral Parliament of South Australia consists of the lower house known as the House of Assembly and the upper house known as the Legislative Council. General elections are held every four years, the last being the 2022 election.

Initially, the Governor of South Australia held almost total power, derived from the letters patent of the imperial government to create the colony. He was accountable only to the British Colonial Office, and thus democracy did not exist in the colony. A new body was created to advise the governor on the administration of South Australia in 1843 called the Legislative Council.[57] It consisted of three representatives of the British Government and four colonists appointed by the governor. The governor retained total executive power.

In 1851, the Imperial Parliament enacted the Australian Colonies Government Act, which allowed for the election of representatives to each of the colonial legislatures and the drafting of a constitution to properly create representative and responsible government in South Australia. Later that year, propertied male colonists were allowed to vote for 16 members on a new 24 seat Legislative Council. Eight members continued to be appointed by the governor.

The main responsibility of this body was to draft a constitution for South Australia. The body drafted the most democratic constitution ever seen in the British Empire and provided for universal manhood suffrage.[58] It created the bicameral Parliament of South Australia. For the first time in the colony, the executive was elected by the people, and the colony used the Westminster system, where the government is the party or coalition that exerts a majority in the House of Assembly. The Legislative Council remained a predominantly conservative chamber elected by property owners.

| Composition of the Parliament of South Australia (2022) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Party | House | Council |

| Labor | 27 | 9 |

| Liberal | 16 | 8 |

| SA-BEST | 0 | 2 |

| Greens | 0 | 2 |

| Independent | 4 | 0 |

| One Nation | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 47 | 22 |

| Source: Electoral Commission SA | ||

Women's suffrage in Australia took a leap forward – enacted in 1895 and taking effect from the 1896 colonial election, South Australia was the first government in Australia and only the second in the world after New Zealand to allow women to vote, and the first in the world to allow women to stand for election.[59] In 1897 Catherine Helen Spence was the first woman in Australia to be a candidate for political office when she was nominated to be one of South Australia's delegates to the conventions that drafted the constitution. South Australia became an original state of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901.

Although the lower house had universal suffrage, the upper house, the Legislative Council, remained the exclusive domain of property owners until the Labor government of Don Dunstan managed to achieve reform of the chamber in 1973. Property qualifications were removed and the Council became a body elected via proportional representation by a single state-wide electorate.[60] Since the following 1975 South Australian state election, no one party has had control of the state's upper house with the balance of power controlled by a variety of minor parties and independents.

Local government

Local government in South Australia is established by the Constitution Act 1934 (SA), the Local Government Act 1999 (SA), and the Local Government (Elections) Act 1999 (SA).[61] South Australia contains 68 councils and 6 Aboriginal and outback communities.[62] Local councils, elected on a four-yearly basis, are responsible for local roads and stormwater management, waste collection, planning and development, fire prevention and hazard management, dog and cat management and control, parking control, public health and food inspections, and other services for their local communities.[61] Councils have the power to raise revenue for their activities, which is mostly achieved through "council rates", a tax based on property valuations. Council rates make up about 70% of council revenue, but account for less than 4% of total taxes paid by Australians.[63]

Demographics

| Birthplace[N 1] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 1,192,546 |

| England | 97,392 |

| India | 27,594 |

| China | 24,610 |

| Italy | 18,544 |

| Vietnam | 14,337 |

| New Zealand | 12,937 |

| Philippines | 12,465 |

| Scotland | 11,993 |

| Germany | 10,119 |

| Greece | 8,682 |

| Malaysia | 7,749 |

| South Africa | 6,610 |

| Afghanistan | 6,313 |

.jpg.webp)

As at December 2021 the population of South Australia was 1,806,599.[2] A majority of the state's population lives within Greater Adelaide's metropolitan area which had an estimated population of 1,333,927 in June 2017.[66] Other significant population centres include Mount Gambier (29,505),[67] Victor Harbor-Goolwa (26,334),[67] Whyalla (21,976),[67] Murray Bridge (18,452),[67] Port Lincoln (16,281),[67] Port Pirie (14,267),[67] and Port Augusta (13,957).[67]

Ancestry and immigration

At the 2016 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 2][68]

28.9% of the population was born overseas at the 2016 census. The five largest groups of overseas-born were from England (5.8%), India (1.6%), China (1.5%), Italy (1.1%) and Vietnam (0.9%).[64][65]

2% of the population, or 34,184 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2016.[N 4][64][65]

Language

At the 2016 census, 78.2% of the population spoke only English at home. The other languages most commonly spoken at home were Italian (1.7%), Standard Mandarin (1.7%), Greek (1.4%), Vietnamese (1.1%), and Cantonese (0.6%).[64][65]

Religion

At the 2016 census, overall 53.9% of responses identified some variant of Christianity. 9% of respondents chose not to state a religion. The most commonly nominated responses were 'No Religion' (35.4%), Catholicism (18%), Anglicanism (10%) and Uniting Church (7.1%).[64][65]

South Australia was the first Australian colony not to have an official state religion,[70] and the colony became attractive to people who had experienced religious discrimination, including Methodists and Unitarians. South Australia also had thousands of Prussian Old Lutheran immigrants, some of whom who established their own form of Lutheranism. As a result, the Lutheran Church of Australia remains separate from the German Lutheran church to this day.[71] South Australia was the location of the first Muslim mosque in Australia.[70]

Most of the state's original colonists were Christian, but of many denominations, most with their own meeting place in the city square. Adelaide has been known as the "City of Churches" since at least 1868.[72] Some of the oldest remaining buildings in the city are churches.[73]

Education

Primary and secondary

On 1 January 2009, the school leaving age was raised to 17 (having previously been 15 and then 16).[74] Education is compulsory for all children until age 17, unless they are working or undergoing other training. The majority of students stay on to complete their South Australian Certificate of Education (SACE). School education is the responsibility of the South Australian government, but the public and private education systems are funded jointly by it and the Commonwealth Government.

The South Australian Government provides, to schools on a per student basis, 89 percent of the total Government funding while the Commonwealth contributes 11 percent. Since the early 1970s it has been an ongoing controversy[75] that 68 percent of Commonwealth funding (increasing to 75% by 2008) goes to private schools that are attended by 32% of the states students.[76] Private schools often counter this by saying that they receive less State Government funding than public schools, and in 2004 the main private school funding came from the Australian government, not the state government.[77]

On 14 June 2013, South Australia became the third Australian state to sign up to the Australian Federal Government's Gonski Reform Program. This will see funding for primary and secondary education to South Australia increased by $1.1 billion before 2019.[78]

The academic year in South Australia generally runs from the end of January until mid-December for primary and secondary schools. The SA schools operate on a four-term basis. Schools are closed for the South Australia public holidays.[79]

Tertiary

There are three public and four private universities in South Australia. The three public universities are the University of Adelaide (established 1874, third oldest in Australia), Flinders University (est. 1966) and the University of South Australia (est. 1991). The four private universities are Torrens University Australia (est. 2013), Carnegie Mellon University - Australia (est. 2006), University College London's School of Energy and Resources (Australia), and Cranfield University. All six have their main campus in the Adelaide metropolitan area: Adelaide and UniSA on North Terrace in the city; CMU, UCL and Cranfield are co-located on Victoria Square in the city, and Flinders at Bedford Park.

The University of Adelaide is part of the Group of Eight, a company of Australia's eight leading research universities.[80] As of 2022, it is ranked by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings as one of the top 100 universities in the world.[81] It was the first university in Australia to admit women to academic courses, doing so in 1881.[80] In 2018, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia announced plans to merge, but these plans did not come to fruition due in part to disagreements over what to name the new university and which of the university's vice-chancellors would become the vice-chancellor of the amalgamated university.[82]

Vocational education

Tertiary vocational education is provided by a range of Registered Training Organisations (RTOs) which are regulated at Commonwealth level. The range of RTOs delivering education include public, private and 'enterprise' providers i.e. employing organisations who run an RTO for their own employees or members.

The largest public provider of vocational education is TAFE South Australia which is made up of colleges throughout the state, many of these in rural areas, providing tertiary education to as many people as possible. In South Australia, TAFE is funded by the state government and run by the South Australian Department of Further Education, Employment, Science and Technology (DFEEST). Each TAFE SA campus provides a range of courses with its own specialisation.

Transport

Historical transport in South Australia

After settlement, the major form of transport in South Australia was ocean transport. Limited land transport was provided by horses and bullocks. In the mid 19th century, the state began to develop a widespread rail network, although a coastal shipping network continued until the post war period.

Roads began to improve with the introduction of motor transport. By the late 19th century, road transport dominated internal transport in South Australia.

Railway

South Australia has four interstate rail connections, to Perth via the Nullarbor Plain, to Darwin through the centre of the continent, to New South Wales through Broken Hill, and to Melbourne–which is the closest capital city to Adelaide.

Rail transport is important for many mines in the north of the state.

The capital Adelaide has a commuter rail network made of electric and diesel electric powered multiple units, with 6 lines between them.

Roads

South Australia has extensive road networks linking towns and other states. Roads are also the most common form of transport within the major metropolitan areas with car transport predominating. Public transport in Adelaide is mostly provided by buses and trams with regular services throughout the day.

Air transport

Adelaide Airport provides regular flights to other capitals, major South Australian towns and many international locations. The airport also has daily flights to several Asian hub airports. Adelaide Metro[83] buses J1 and J1X connect to the city (approx. 30 minutes travel time), as well as other services to other parts of Adelaide. Standard fares apply and tickets may be purchased from a ticket machine at the airport bus stop. Maximum charge (September 2016) for Metroticket is $5.30; off-peak and seniors discounts may apply.

River transport

The River Murray was formerly an important trade route for South Australia, with paddle steamers linking inland areas and the ocean at Goolwa.

Sea transport

South Australia has a container port at Port Adelaide. There are also numerous important ports along the coast for minerals and grains.

The passenger terminal at Port Adelaide periodically sees cruise liners.

Kangaroo Island is dependent on the Sea Link ferry service between Cape Jervis and Penneshaw.

Cultural life

South Australia has been known as "the Festival State" for many years, for its abundance of arts and gastronomic festivals.[84] While much of the arts scene is concentrated in Adelaide, the state government has supported regional arts actively since the 1990s. One of the manifestations of this was the creation of Country Arts SA, created in 1992.[85]

Diana Laidlaw did much to further the arts in South Australia during her term as Arts Minister from 1993 to 2002, and after Mike Rann assumed government in 2002, he created a strategic plan in 2004 (updated 2007) which included furthering and promoting the arts in South Australia under the topic heading "Objective 4: Fostering Creativity and Innovation".[86][87]

In September 2019, with the arts portfolio now subsumed within the Department of the Premier and Cabinet (DPC) after the election of Steven Marshall as Premier, and the 2004 strategic plan having been deleted from the website in 2018,[88] the "Arts and Culture Plan, South Australia 2019–2024" was created by the department.[89] Marshall said when launching the plan: “The arts sector in South Australia is already very strong but it's been operating without a plan for 20 years”.[90] However the plan does not signal any new government support, even after the government's A$31.9 million cuts to arts funding when Arts South Australia was absorbed into DPC in 2018. Specific proposals within the plan include an “Adelaide in 100 Objects” walking tour, a new shared ticketing system for small to medium arts bodies, a five-year-plan to revitalise regional art centres, creation of an arts-focussed high school, and a new venue for the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.[91]

Sport

Australian rules football

Australian rules football is the most popular spectator sport in South Australia. In 2006, South Australians had the highest attendance rate for the sport of any state, with 31% of South Australians attending a match in the previous twelve months.[92] South Australia fields two teams in the Australian Football League (AFL): the Adelaide Football Club and Port Adelaide Football Club. The two teams have an intense rivalry called the Showdown.[93] The traditional home of Australian rules football in South Australia was Football Park in the western suburb of West Lakes, which was the home ground of both AFL teams until 2013. Since 2014, both teams have used Adelaide Oval, near the city center, as their home ground.[94]

The South Australian National Football League (SANFL), which was the premier league in the state before the advent of the Australian Football League, is a popular local league comprising ten teams: Sturt, Port Adelaide, Adelaide, West Adelaide, South Adelaide, North Adelaide, Norwood, Woodville/West Torrens, Glenelg and Central District.

The Adelaide Footy League comprises 68 member clubs playing over 110 matches per week across ten senior divisions and three junior divisions. It is one of Australia's largest and strongest Australian rules football associations.[95]

Cricket

Cricket is the most popular summer sport in South Australia and attracts big crowds. South Australia has a professional cricket team, the West End Redbacks, who play at Adelaide Oval in the Adelaide Park Lands during the summer; they won their first title since 1996 in the summer of 2010–11. Many international matches have been played at the Adelaide Oval; it was one of the host cities of 2015 Cricket World Cup, and for many years it hosted the Australia Day One Day International. South Australia is also home to the Adelaide Strikers, an Australian men's professional Twenty20 cricket team, that competes in Australia's domestic Twenty20 cricket competition, the Big Bash League.

Association football

Adelaide United represents South Australia in soccer in the men's A-League and women's W-League. The club's home ground is Hindmarsh Stadium (Coopers Stadium), but it occasionally plays games at the Adelaide Oval.

The club was founded in 2003 and are the 2015–16 season champions of the A-League. The club was also premier in the inaugural 2005–06 A-League season, finishing 7 points clear of the rest of the competition, before finishing 3rd in the finals. Adelaide United was also a Grand Finalist in the 2006–07 and 2008–09 seasons. Adelaide is the only A-League club to have progressed past the group stages of the Asian Champions League on more than one occasion.[96]

Adelaide City remains South Australia's most successful club, having won three National Soccer League titles and three NSL Cups. City was the first side from South Australia to ever win a continental title when it claimed the 1987 Oceania Club Championship and it has also won a record 17 South Australian championships and 17 Federation Cups.

West Adelaide became the first South Australian club to be crowned Australian champion when it won the 1978 National Soccer League title. Like City, it now competes in the National Premier Leagues South Australia and the two clubs contest the Adelaide derby.

Basketball

Basketball also has a big following in South Australia, with the Adelaide 36ers playing in the Adelaide Entertainment Centre. The 36ers have won four championships in the last 20 years in the National Basketball League. The Adelaide Entertainment Centre, located in Hindmarsh, is the home of basketball in the state.

Mount Gambier also has a national basketball team – the Mount Gambier Pioneers. The Pioneers play at the Icehouse (Bern Bruning Basketball Stadium), which seats over 1,000 people and is also home to the Mount Gambier Basketball Association. The Pioneers won the South Conference in 2003 and the Final in 2003; this team was rated second in the top five teams to have ever played in the league. In 2012, the club entered its 25th season, with a roster of 10 senior players (two imports) and three development squad players.

Motorsport

Australia's premier motorsport series, the Supercars Championship, has visited South Australia each year since 1999. South Australia's Supercars event, the Adelaide 500, is staged on the Adelaide Street Circuit, a temporary track laid out through the streets and parklands to the east of the Adelaide city centre. Attendance for the 2010 event totalled 277,800.[97] An earlier version of the Adelaide Street Circuit played host to the Australian Grand Prix, a round of the FIA Formula One World Championship, each year from 1985 to 1995.

Mallala Motor Sport Park, a permanent circuit located near the town of Mallala, 58 km north of Adelaide, caters for both state and national level motor sport throughout the year.

The Bend Motorsport Park, is another permanent circuit, located just outside of Tailem Bend.[98]

Other sports

Sixty-three percent of South Australian children took part in organised sports in 2002–2003.[99]

The ATP Adelaide was a tennis tournament held from 1972 to 2008 that then moved to Brisbane and was replaced with The World Tennis Challenge a Professional Exhibition Tournament that is part of the Australian Open Series. Also, the Royal Adelaide Golf Club has hosted nine editions of the Australian Open, with the most recent being in 1998.

The state has hosted the Tour Down Under cycle race since 1999.[100]

Places

Crime

Crime in South Australia is managed by the South Australia Police (SAPOL), various state and federal courts in the criminal justice system and the state Department for Correctional Services, which administers the prisons and remand centre.

Crime statistics for all categories of offence in the state are provided on the SAPOL website, in the form of rolling 12-month totals.[101] Crime statistics from the 2017–18 national ABS Crime Victimisation Survey show that between the years 2008–09 and 2017–18, the rate of victimisation in South Australia declined for assault and most household crime types.[102]

In 2013 Adelaide was ranked the safest capital city in Australia.[103]

See also

- Australia

- Outline of Australia

- Index of Australia-related articles

- Adelaide

- Country Fire Service

- Proclamation Day: 28 December 1836

- South Australian Ambulance Service

- South Australian English

- Symbols of South Australia

Food and drink

Lists

- List of amphibians of South Australia

- List of cities and towns in South Australia

- List of festivals in Australia#South Australia

- List of films shot in Adelaide

- List of highways in South Australia

- List of people from Adelaide

- Local Government Areas of South Australia

- List of public art in South Australia

- Tourist attractions in South Australia

Notes

- In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately

- As a percentage of 1,227,355 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census.

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[69]

- Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

Footnotes

- "Wordwatch: Croweater". ABC NewsRadio. Archived from the original on 15 September 2005. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- "National, state and territory population – March 2021". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 26 September 2022. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- "5220.0 – Australian National Accounts: State Accounts, 2019–20". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- Area of Australia - States and Territories Geoscience Australia. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- Most Australians describe the body of water south of the continent as the Southern Ocean, rather than the Indian Ocean as officially defined by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). In the year 2000, a vote of IHO member nations defined the term "Southern Ocean" as applying only to the waters between Antarctica and 60 degrees south latitude.

- South Australian Police Historical Society Inc. Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 13 September 2011.

- Anderson, Margaret. "The first reading of the proclamation". SA History Hub. History Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- "Kangaroo Island Council – Welcome". Kangaroo Island Council. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- "The Wakefield Model of Systematic Colonisation in South Australia". University of South Australia. 2008.

- R.J. Lampert (1979): Aborigines. In Tyler, M.J., Twidale, C.R. & Ling, J.K. (Eds) Natural History of Kangaroo Island. Royal Society of South Australia Inc. ISBN 0-9596627-1-5

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2020), Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199812790 / ISBN 9780199812776

- Australian Geographical Society.; Australian National Publicity Association.; Australian National Travel Association. (1934), Walkabout, Australian National Travel Association, retrieved 7 January 2019

- "Transcript of the South Australia Act, 1834" (PDF). Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Documenting Democracy".

- Ngadjuri Walpa Juri Lands and Heritage Association (n.d.). Gnadjuri. SASOSE Council Inc. ISBN 978-0-646-42821-5.

- Sendziuk, P. (2012): No convicts here: reconsidering South Australia's foundation myth. In: Foster, R. & Sendziuk, P. (Eds.) Turning points: chapters in South Australian history. Wakefield Press. ISBN 978 1 74305 119 1

- "History of Adelaide Gaol". Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "Highest Mountains". Geoscience Australia. Archived from the original on 21 April 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2006.

- "South Australia". Wine Australia. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- Henzell, Ted (2007). Australian Agriculture: Its History and Challenges. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 9780643993426.

- Territorial evolution of Australia – 6 July 1863

- "Climate and Weather". Government of South Australia. Atlas South Australia. 28 April 2004. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- "Rainfall and Temperature Records: National" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. Bureau of Meteorology. 1 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- "Region summary: South Australia". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- "Australia's Trade by State and Territory 2013–14" (PDF). Australia Unlimited. February 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Puddy, Rebecca (31 May 2012). "South Australia loses AAA rating in credit rating downgrade". The Australian. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Inquiry into Local Government and Cost Shifting" (PDF). Australian House of Representatives. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- "Gross State Product" (PDF). Treasury South Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Wright, Shane (19 November 2021). "The little economies that could: SA and Tasmania lead the nation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Lewis, Dave. ""Crop and Pasture Report South Australia, 2021-22 Harvest"" (PDF). Government of South Australia, Department of Primary Industries and Regions. South Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA). Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- "Horticulture in South Australia" (PDF). Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA). The Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA). Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- "Grape and wine". Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA). The Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA). 14 May 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- "Wind Energy – How it works". Clearenergycouncil. Archived from the original on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- "Hornsdale Power Reserve". Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Gemma Daley; Tan Hwee Ann (3 April 2006). "Australia, China Sign Agreements for Uranium Trade (Update5)". Bloomberg. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Ian Lambert; Subhash Jaireth; Aden McKay; Yanis Miezitis (December 2005). "Why Australia has so much uranium". AusGeo News. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "FACTBOX-BHP Billiton's huge Olympic Dam mine". Reuters. 21 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Sky News Australia – Finance Article

- BHP shelves Olympic Dam as profit falls a third. ABC News, 22 August 2012. Retrieved on 16 July 2013.

- Shang, Phoebe. "Opal Mining in Coober Pedy: History and Methods". IGS. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- Edwards, Verity (3 May 2008). "Education attracts record numbers". The Weekend Australian.

- Broadstock, Amelia (6 May 2015). "International Uni student numbers a billion dollar boom for Adelaide". The City Messenger.

- Hodges, Lucy (29 May 2008). "Brave new territory: University College London to open a branch in Australia". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "About Heinz Australia: Carnegie Mellon Heinz College". Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011.

- Edwards, Verity (3 May 2008). "RI Australia plugs into world science". The Weekend Australian.

- History Archived 16 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Our research Archived 16 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science

- About us Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, History Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine , Hanson Institute

- The Australian Wine Research Institute (AWRI) Archived 25 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, awri.com.au

- Australian Centre for Plant Functional Genomics (ACPFG) Archived 18 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, acpfg.com.au

- "Waite Campus, Urrbrae". CSIRO. 6 September 2019. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Livestock – Glenside Laboratories". Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- "SARDI". Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- "A great of the SA science world". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- R v Governor of South Australia; Ex parte Vardon [1907] HCA 31, (1907) 4 CLR 1497, High Court (Australia).

- "Legislative Council 1843–1856". Parliament of South Australia. 2005. Archived from the original on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2006.

- Change name (28 January 2011). "The Right to Vote in Australia". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "Women's Suffrage Petition 1894: parliament.sa.gov.au" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Dunstan, Don (1981). Felicia: The political memoirs of Don Dunstan. Griffin Press Limited. pp. 214–215. ISBN 0-333-33815-4.

- "Local government in SA". Local Government Association of South Australia. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "SA councils list & map". Local Government Association of South Australia. 15 August 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "Council rates". Local Government Association of South Australia. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "2016 Census Community Profiles: South Australia". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "South Australia (4) 984274.9 sq Kms". www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016–17: Main Features". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018. Estimated resident population, 30 June 2017.

- "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016–17: Population Estimates by Significant Urban Area, 2007 to 2017". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018. Estimated resident population, 30 June 2017.

- "2016 Census Community Profiles: Greater Adelaide". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (January 1995). "Feature Article – Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Australia (Feature Article)". Australian Bureau of Statistics.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Religion : Beginnings". SA Memory. 23 May 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "Religion : Diversity". SA Memory. 7 December 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "The Week's News". Adelaide Observer. Vol. XXVI, no. 1389. South Australia. 16 May 1868. p. 9. Retrieved 12 April 2023 – via National Library of Australia. Earlier instances may be found without capital "C"s.

- "Religion : City of churches". SA Memory. 7 December 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- Owen, Michael (22 May 2006). "School leaving age to be raised". The Advertiser. News Corp. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2006.

- "The Redefinition of Public Education". Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- "Chapter 2: Resourcing Australia's schools". Ministerial Council National Report on Schooling in Australia. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013.

- Bill Daniels (12 April 2004). "Government funding should encourage private schools not penalise them". Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- "South Australia signs up to Federal Government's Gonski education reforms". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 June 2013.

- "SA School Holidays, Public Holidays & School Terms 2022 - 2023". School Holidays. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- Craddock, Alex (30 September 2019). "A Guide to Universities in Adelaide". Insider Guides. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "What's the best university in the world? What's the best Australian uni? Here's what the World University Rankings list says". ABC News. 12 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- Siebert, Bension (21 January 2021). "University of Adelaide, UniSA merger proposal failed after uncertainty over name and leadership". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "Adelaide Metro". adelaidemetro.com.au. Service SA. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Wallace, Ilona (31 March 2015). "Is South Australia still the Festival State?". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Lensink, Michelle (26 November 2003). "Laidlaw, Hon. Diana". Hon. Michelle Lensink MLC. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "South Australia'S Strategic Plan 2007" (Document). Government of South Australia. 2007.

- Mackie, Greg (13 July 2017). "Finding the Next Wave: Innovation and its Discontents". University of Adelaide Cultural Oration 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Smith, Matt (9 June 2018). "Ex-premier Mike Rann's vision for South Australia purged after 14 years by new ruling Liberals". AdelaideNow. The Advertiser. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Arts and Culture Plan South Australia 2019–2024". Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Richards, Stephanie (2 September 2019). "Marshall "considering" concert hall as part of new arts plan". InDaily. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Marsh, Walter (2 September 2019). "New Arts Plan and review suggest arts sector learns to live with less government support". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "4174.0 - Sports Attendance, Australia, 2005-06". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 25 January 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Rucci, Michelangelo (6 August 2021). "Culture war: getting the lowdown on Showdown". InDaily. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- "Adelaide Oval success boosts AFL crowd figures". ABC.net.au. 29 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- "South Australian Amateur Football League". Archived from the original on 2 July 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- "Reds finalise squad for ACL Knockout Stage – Adelaide United FC 2013". Football Australia. 24 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Early March the only date for Clipsal 500". SpeedCafe. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Strathearn, Peri (8 March 2016). "The Bend Motorsport Park: Tailem Bend raceway, former SA Motorsport Park and Mitsibushi test track, has new official name". Murray Valley Standard. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018.

- "Children's Participation in Cultural and Leisure Activities", April 2003, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Keane, Daniel (12 March 2015). "Victoria may gloat about poaching the Grand Prix, but SA gained a lot by losing it". ABC News. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- "Crime statistics". South Australia Police. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- "Main Features - South Australia". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 13 February 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- "Adelaide's nation's safest city, according to Suncorp study - Adelaide Now". Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

Further reading

- Bull, John Wrathall (1884). Early Experiences of Life in South Australia and an Extended Colonial History. Adelaide: E.S. Wigg & son , pub.

- Stow, Jefferson Pickman (1884). South Australia: Its History, Productions, and Natural Resources. Adelaide: E. Spiller, government printer.

- Finniss, B.T. (1886). The Constitutional History of South Australia During Twenty-One Years from the Foundation of the Settlement in 1836 to the Inauguration of Responsible Government in 1857 (PDF). Adelaide: W.C. Rigby.

- Hodder, Edwin (1893). The history of South Australia from its foundation to the year of its jubilee: Vol I (PDF). London: S. Low, Marston & Company, Limited.

- Hodder, Edwin (1893). The history of South Australia from its foundation to the year of its jubilee: Vol II (PDF). London: S. Low, Marston & Company, Limited.

- Pascoe, J.J. (1901). History of Adelaide and vicinity : with a general sketch of the province of South Australia and biographies of representative men. Adelaide: Hussey & Gillingham. ISBN 9780858720329.

- Blacket, John (1911). History of South Australia: a romantic and successful experiment in colonization (PDF). Adelaide: Hussey & Gillingham Limited.

- Pike, Douglas. (1967) Paradise of Dissent: South Australia 1829-1857 (Melbourne UP, 2nd edition)

- Robbins, E. Jane; Robbins, John R. (1987). A Glossery of Local Government Areas in South Australia, 1840-1985 (PDF). Historical Society of South Australia. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- Dorothy Jauncey, Bardi Grubs and Frog Cakes – South Australian Words, Oxford University Press (2004) ISBN 0-19-551770-9

- Jaensch, Dean (2002). "Community access to the electoral processes in South Australia since 1850". South Australian State Electoral Office.

- Sendziuk, Paul; Foster, Robert (2018). A History of South Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107623651.

External links

Media related to South Australia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to South Australia at Wikimedia Commons South Australia travel guide from Wikivoyage

South Australia travel guide from Wikivoyage Geographic data related to South Australia at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to South Australia at OpenStreetMap- sa.gov.au

- Official Insignia and Emblems Page

- South Australia's greenhouse (climate change) strategy (2007–2020)

- Ground Truth – towards an Environmental History of South Australia Archived 7 October 2001 at the Wayback Machine