Solid South

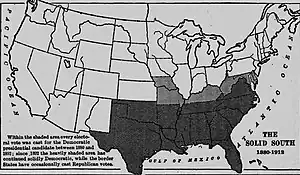

The Solid South or the Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed between the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. During this period, the Democratic Party overwhelmingly controlled southern state legislatures, and most local, state and federal officeholders in the South were Democrats. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Southern Democrats disenfranchised blacks in all Southern states, along with a few non-Southern states doing the same as well. This resulted essentially in a one-party system, in which a candidate's victory in Democratic primary elections was tantamount to election to the office itself. White primaries were another means that the Democrats used to consolidate their political power, excluding blacks from voting in primaries.[1]

Solid South (Southern bloc) | |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1877 |

| Dissolved | 1964 |

| Preceded by | Redeemers |

| Succeeded by | Dixiecrats (1948) |

| Ideology | American conservatism (majority) Segregationism White supremacy States' rights |

| National affiliation | Democratic Party |

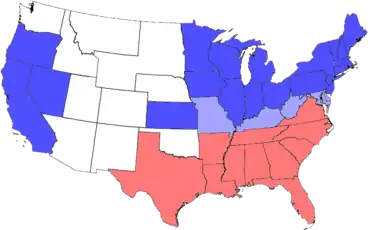

The "Solid South" is a loose term referring to the states that made up the voting bloc at any point in time. The Southern region, as currently defined by the Census Bureau, comprises sixteen states: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia, plus Washington, D.C.[2] The idea of the Solid South shifted over time and did not always necessarily correspond to the census definition.

After Reconstruction, all the former slave states were dominated by the Democratic Party for at least two decades. Delaware, one of the slaveholding border states that had remained in the Union during the Civil War, was considered a reliable state for the Democratic Party,[3] as was Missouri, classified as a Midwestern state by the U.S. Census Bureau. From the early part of the 20th century on, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and West Virginia ceased to be reliably Democratic (although West Virginia once again became a reliably Democratic state with the New Deal era).

Background

At the start of the American Civil War, there were 34 states in the United States, 15 of which were slave states. Slavery was also legal in the District of Columbia. Eleven of these slave states plus an additional two claimed by the Confederacy seceded from the United States to form the Confederacy: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. The southern slave states that stayed in the Union were Maryland, Missouri, Delaware, and Kentucky, and they were referred to as the border states. Kentucky and Missouri both had dual competing Confederate and Unionist governments with the Confederate government of Kentucky and Confederate government of Missouri. The Confederacy controlled more than half of Kentucky and the southern portion of Missouri early in the war but largely lost control in both states after 1862. In 1861, West Virginia was created out of Virginia, and admitted in 1863 and considered a border state though was highly contested by the Confederacy.

By the time the Emancipation Proclamation was made in 1863, Tennessee was already under Union control. Accordingly, the Proclamation applied only to the 10 remaining Confederate states. Some of the border states abolished slavery before the end of the Civil War—Maryland in 1864,[4] Missouri in 1865,[5] one of the Confederate states, Tennessee in 1865,[6] West Virginia in 1865,[7] and the District of Columbia in 1862. However, slavery persisted in Delaware,[8] Kentucky,[9] and 10 of the 11 former Confederate states, until the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery throughout the United States on December 18, 1865.

Democratic dominance of the South originated in the struggle of white Southerners during and after Reconstruction (1865–1877) to reestablish white supremacy and disenfranchise black people. The U.S. government under the Republican Party had defeated the Confederacy, abolished slavery, and enfranchised black people. In several states, black voters were a majority or close to it. Republicans supported by black people controlled state governments in these states. Thus the Democratic Party became the vehicle for the white supremacist "Redeemers". The Ku Klux Klan, as well as other insurgent paramilitary groups such as the White League and Red Shirts from 1874, acted as "the military arm of the Democratic party" to disrupt Republican organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voters.[10]

History

1870s to 1910s

By 1876, "Redeemer" Democrats had taken control of all state governments in the South. From then until the 1960s, state and local government in the South was almost entirely monopolized by Democrats. The Democrats elected all but a handful of U.S. Representatives and Senators, and Democratic presidential candidates regularly swept the region – from 1880 through 1944, winning a cumulative total of 182 of 187 states. The Democrats reinforced the loyalty of white voters by emphasizing the suffering of the South during the war at the hands of "Yankee invaders" under Republican leadership, and the noble service of their white forefathers in "the Lost Cause". This rhetoric was effective with many Southerners. However, this propaganda was totally ineffective in areas that had been loyal to the Union during the war, such as eastern Tennessee. Most of East Tennessee welcomed U.S. troops as liberators, and voted Republican even in the Solid South period.[11]

Even after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures, some black candidates were elected to local offices and state legislatures in the South. Black U.S. Representatives were elected from the South as late as the 1890s, usually from overwhelmingly black areas. Also in the 1890s, the Populists developed a following in the South, among poor white people who resented the Democratic Party establishment. Populists formed alliances with Republicans (including black Republicans) and challenged the Democratic bosses, even defeating them in some cases.[12]

To prevent such coalitions in the future and to end the violence associated with suppressing the black vote during elections, Southern Democrats acted to disfranchise both black people and poor white people. From 1890 to 1910, beginning with Mississippi, Southern states adopted new constitutions and other laws including various devices to restrict voter registration, disfranchising virtually all black and many poor white residents.[13] These devices applied to all citizens; in practice they disfranchised most black citizens and also "would remove [from voter registration rolls] the less educated, less organized, more impoverished whites as well – and that would ensure one-party Democratic rules through most of the 20th century in the South".[14][15] All the Southern states adopted provisions that restricted voter registration and suffrage, including new requirements for poll taxes, longer residency, and subjective literacy tests. Some also used the device of grandfather clauses, exempting voters who had a grandfather voting by a particular year (usually before the Civil War, when black people could not vote.)[16]

White Democrats also opposed Republican economic policies such as the high tariff and the gold standard, both of which were seen as benefiting Northern industrial interests at the expense of the agrarian South in the 19th century. Nevertheless, holding all political power was at the heart of their resistance. From 1876 through 1944, the national Democratic party opposed any calls for civil rights for black people. In Congress Southern Democrats blocked such efforts whenever Republicans targeted the issue.[17]

White Democrats passed "Jim Crow" laws which reinforced white supremacy through racial segregation.[18] The Fourteenth Amendment provided for apportionment of representation in Congress to be reduced if a state disenfranchised part of its population. However, this clause was never applied to Southern states that disenfranchised black residents. No black candidate was elected to any office in the South for decades after the turn of the century; and they were also excluded from juries and other participation in civil life.[13]

Electoral dominance

Democratic candidates won by large margins in a majority of Southern states in every presidential election from 1876 to 1948, except for 1928, when the Democratic candidate was Al Smith, a Catholic New Yorker; and even in that election, the divided South provided Smith with nearly three-fourths of his electoral votes. Scholar Richard Valelly credited Woodrow Wilson's 1912 election to the disfranchisement of black people in the South, and also noted far-reaching effects in Congress, where the Democratic South gained "about 25 extra seats in Congress for each decade between 1903 and 1953".[lower-alpha 1][13]

In the Deep South (South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana), Democratic dominance was overwhelming, with Democrats routinely receiving 80%–90% of the vote, and only a tiny number of Republicans holding state legislative seats or local offices. Mississippi and South Carolina were the most extreme cases – between 1900 and 1944, only in 1928, when the three subcoastal Mississippi counties of Pearl River, Stone and George went for Hoover, did the Democrats lose even one of these two states' counties in any presidential election.[19] In the remaining states, the German-American Texas counties of Gillespie and Kendall, and a number of counties in Appalachian parts of Alabama and Georgia, would vote Republican in presidential elections through this period.[20] In the Upper South (Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Virginia), Republicans retained a significant presence mainly in these remote Appalachian and Ozark regions which supported the Union during the Civil War,[20] even winning occasional governorships and often drawing over 40% in presidential votes.

1920s onwards

By the 1920s, as memories of the Civil War faded, the Solid South cracked slightly. For instance, a Republican was elected U.S. Representative from Texas in 1920, serving until 1932. The Republican national landslides in 1920 and 1928 had some effects. In the 1920 elections, Tennessee elected a Republican governor and five out of 10 Republican U.S. Representatives, and became the first former Confederate state to vote for a Republican candidate for U.S. President since Reconstruction. However, with the Democratic national landslide of 1932, the South again became solidly Democratic.

In the 1930s, black voters outside the South largely switched to the Democrats, and other groups with an interest in civil rights (notably Jews, Catholics, and academic intellectuals) became more powerful in the party. This led to the national Democrats adopting a civil rights plank in 1948. In response, a faction of Deep South Democrats ran their own segregationist "Dixiecrat" presidential ticket, which carried four states: South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.[21] Even before then, a number of conservative Southern Democrats felt chagrin at the national party's growing friendliness to organized labor during the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, and began splitting their tickets as early as the 1930s.

Southern demography also began to change. From 1910 through 1970, about 6.5 million black Southerners moved to urban areas in other parts of the country in the Great Migration, and demographics began to change Southern states in other ways. Florida began to expand rapidly, with retirees and other migrants from other regions becoming a majority of the population. Many of these new residents brought their Republican voting habits with them, diluting traditional Southern hostility to the Republicans. The Republican Party began to make gains in the South, building on other cultural conflicts as well. By the mid-1960s, changes had come in many of the southern states. Former Dixiecrat Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina changed parties in 1964; Texas elected a Republican Senator in 1961; Florida and Arkansas elected Republican governors in 1966. In the Upper South, where Republicans had always been a small presence, Republicans gained a few seats in the House and Senate.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the South was still overwhelmingly Democratic at the state level, with majorities in all state legislatures and most U.S. House delegations. Over the next thirty years, this gradually changed. Veteran Democratic officeholders retired or died, and older voters who were still rigidly Democratic also died off. There were also increasing numbers of migrants from other areas, especially in Florida, Texas, Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina. As part of the Republican Revolution in the 1994 elections, Republicans captured a majority of the U.S. House's southern seats for the first time. As of 2021, they account for a majority of each Southern state's House delegation apart from Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware.

Following the 2016 elections, when Republicans won the Kentucky House of Representatives, every state legislative chamber in the South had a Republican majority for the first time ever.[22] This would remain the case until Democrats regained both Houses of the Virginia Legislature in 2019.

Today, the South is considered a Republican stronghold at the state and federal levels. Some political experts identify a re-Southernization of politics and culture in the Clinton presidency coinciding with House and Senate leading positions held by southerners.

West Virginia

For West Virginia, "reconstruction, in a sense, began in 1861".[23] Unlike the other border states, West Virginia did not send the majority of its soldiers to the Union.[24] The prospect of those returning ex-Confederates prompted the Wheeling state government to implement laws that restricted their right of suffrage, practicing law and teaching, access to the legal system, and subjected them to "war trespass" lawsuits.[25] The lifting of these restrictions in 1871 resulted in the election of John J. Jacob, a Democrat, to the governorship. It also led to the rejection of the war-time constitution by public vote and a new constitution written under the leadership of ex-Confederates such as Samuel Price, Allen T. Caperton and Charles James Faulkner. In 1876 the state Democratic ticket of eight candidates were all elected, seven of whom were Confederate veterans.[26] For nearly a generation West Virginia was part of the Solid South.[27][28]

However, Republicans returned to power in 1896, controlling the governorship for eight of the next nine terms, and electing 82 of 106 U.S. Representatives. In 1932, as the nation swung to the Democrats, West Virginia became solidly Democratic. It was perhaps the most reliably Democratic state in the nation between 1932 and 1996, being one of just two states (along with Minnesota) to vote for a Republican president as few as three times in that interval. Moreover, unlike Minnesota (or other nearly as reliably Democratic states like Massachusetts and Rhode Island), it usually had a unanimous (or nearly unanimous) congressional delegation and only elected two Republicans as governor (albeit for a combined 20 years between them). West Virginian voters shifted toward the Republican Party from 2000 onward, as the Democratic Party became more strongly identified with environmental policies anathema to the state's coal industry and with socially liberal policies, and it can now be called a solidly red state.[29][30]

Presidential voting

The 1896 election resulted in the first break in the Solid South. Florida politician Marion L. Dawson, writing in the North American Review, observed: "The victorious party not only held in line those States which are usually relied upon to give Republican majorities ... More significant still, it invaded the Solid South, and bore off West Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky; caused North Carolina to tremble in the balance and reduced Democratic majorities in the following States: Alabama, 39,000; Arkansas, 29,000; Florida, 6,000; Georgia, 49,000; Louisiana, 33,000; South Carolina, 6,000; and Texas, 29,000. These facts, taken together with the great landslide of 1894 and 1895, which swept Missouri and Tennessee, Maryland and Kentucky over into the country of the enemy, have caused Southern statesmen to seriously consider whether the so-called Solid South is not now a thing of past history".[31] The South stayed mostly a single bloc until the 1960s, with a brief break in the 1920s, however.

In the 1904 election, Missouri supported Republican Theodore Roosevelt, while Maryland awarded its electors to Democrat Alton Parker, despite Roosevelt's winning by 51 votes.[32] By the 1916 election, disfranchisement of blacks and many poor whites was complete, and voter rolls had dropped dramatically in the South. Closing out Republican supporters gave a bump to Woodrow Wilson, who took all the electors across the South (apart from Delaware and West Virginia), as the Republican Party was stifled without support by African Americans.[13]

The 1920 election was a referendum on President Wilson's League of Nations. Pro-isolation sentiment in the South benefited Republican Warren G. Harding, who won Tennessee, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Maryland. In 1924, Republican Calvin Coolidge won Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland; and in 1928, Herbert Hoover, perhaps benefiting from bias against his Democratic opponent Al Smith (who was a Roman Catholic and opposed Prohibition), won not only those Southern states that had been carried by either Harding or Coolidge (Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Maryland), but also won Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia, none of which had voted Republican since Reconstruction. He furthermore came within 2.5% of carrying the Deep South state of Alabama. (All of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover carried the two Southern states that had supported Hughes in 1916, West Virginia and Delaware.)

Al Smith had received serious backlash as a Catholic in the largely Protestant South in 1928, losing several states in the Outer South, only managing to hold Arkansas outside the Deep South. Smith had also nearly lost Alabama, which he held by 3%, which had Hoover won, would have physically split the Solid South. The South appeared "solid" again during the period of Roosevelt's political dominance, as his welfare programs and military buildup invested considerable money in the South, benefiting many of its citizens, including during the Dust Bowl.

Democratic President Harry S. Truman's support of the civil rights movement, combined with the adoption of a civil rights plank in the 1948 Democratic platform, prompted many Southerners to walk out of the Democratic National Convention and form the Dixiecrat Party. This splinter party played a significant role in the 1948 election; the Dixiecrat candidate, Strom Thurmond, carried Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and his native South Carolina.

In the elections of 1952 and 1956, the popular Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of the Allied armed forces during World War II, carried several Southern states, with especially strong showings in the new suburbs. Most of the Southern states he carried had voted for at least one of the Republican winners in the 1920s, but in 1956, Eisenhower carried Louisiana, becoming the first Republican to win the state since Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876. The rest of the Deep South voted for his Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson.

In the 1960 election, the Democratic nominee, John F. Kennedy, continued his party's tradition of selecting a Southerner as the vice presidential candidate (in this case, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas). Kennedy and Johnson, however, both supported civil rights. In October 1960, when Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested at a peaceful sit-in in Atlanta, Georgia, Kennedy placed a sympathetic phone call to King's wife, Coretta Scott King, and Kennedy's brother Robert F. Kennedy helped secure King's release. King expressed his appreciation for these calls. Although King made no endorsement, his father, who had previously endorsed Republican Richard Nixon, switched his support to Kennedy.

Because of these and other events, the Democrats lost ground with white voters in the South, as those same voters increasingly lost control over what was once a whites-only Democratic Party in much of the South. The 1960 election was the first in which a Republican presidential candidate received electoral votes from the former Confederacy while losing nationally. Nixon carried Virginia, Tennessee, and Florida. Though the Democrats also won Alabama and Mississippi, slates of unpledged electors, representing Democratic segregationists, awarded those states' electoral votes to Harry Byrd, rather than Kennedy.

The parties' positions on civil rights continued to evolve in the run up to the 1964 election. The Democratic candidate, Johnson, who had become president after Kennedy's assassination, spared no effort to win passage of a strong Civil Rights Act of 1964. After signing the landmark legislation, Johnson said to his aide, Bill Moyers: "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come."[33] In contrast, Johnson's Republican opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, voted against the Civil Rights Act, believing it enhanced the federal government and infringed on the private property rights of businessmen. Goldwater did support civil rights in general and universal suffrage, and voted for the 1957 Civil Rights Act (though casting no vote on the 1960 Civil Rights Act), as well as voting for the 24th Amendment, which banned poll taxes as a requirement for voting. This was one of the devices that states used to disfranchise African Americans and the poor.

That November, Johnson won a landslide electoral victory, and the Republicans suffered significant losses in Congress. Goldwater, however, besides carrying his home state of Arizona, carried the Deep South: voters in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina had switched parties for the first time since Reconstruction. Goldwater notably won only in Southern states that had voted against Republican Richard Nixon in 1960, while not winning a single Southern state which Nixon had carried. Previous Republican inroads in the South had been concentrated on high-growth suburban areas, often with many transplants, as well as on the periphery of the South.

According to a quantitative analysis done by Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington, racism played a central role in the decline in relative white Southern Democratic identification.[34]

Southern strategy

1965 to 2010

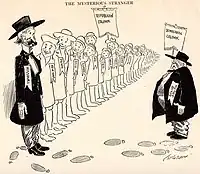

In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon saw the cracks in the Solid South as an opportunity to tap into a group of voters who had historically been beyond the reach of the Republican Party. With the aid of Harry Dent and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, Nixon ran his 1968 campaign on states' rights and "law and order". As a key component of this strategy, he selected as his running mate Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew.[35] Liberal Northern Democrats accused Nixon of pandering to Southern whites, especially with regard to his "states' rights" and "law and order" positions, which were widely understood by black leaders to legitimize the status quo of Southern states' discrimination.[36] This tactic was described in 2007 by David Greenberg in Slate as "dog-whistle politics".[37] According to an article in The American Conservative, Nixon adviser and speechwriter Pat Buchanan disputed this characterization.[38][39]

The independent candidacy of George Wallace, former Democratic governor of Alabama, partially negated Nixon's Southern Strategy.[40] With a much more explicit attack on integration and black civil rights, Wallace won all but two of Goldwater's states (the exceptions being South Carolina and Arizona) as well as Arkansas and one of North Carolina's electoral votes. Nixon picked up Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware. The Democrat, Hubert Humphrey, won Texas, heavily unionized West Virginia, and heavily urbanized Maryland. Writer Jeffrey Hart, who worked on the Nixon campaign as a speechwriter, said in 2006 that Nixon did not have a "Southern Strategy", but "Border State Strategy" as he said that the 1968 campaign ceded the Deep South to George Wallace. Hart suggested that the press called it a "Southern Strategy" as they are "very lazy".[41]

The 1968 election had been the first election in which both the Upper South and Deep South bolted from the Democratic party simultaneously. The Upper South had backed Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956, as well as Nixon in 1960. The Deep South had backed Goldwater just four years prior. Despite the two regions of the South still backing different candidates, Wallace in the Deep South and Nixon in the Upper South, only Texas, Maryland, and West Virginia had held up against the majority Nixon-Wallace vote for Humphrey. By 1972, Nixon had swept the South altogether, Outer and Deep South alike, marking the first time in American history a Republican won every Southern state.

At the 1976 election, Jimmy Carter, a Southern governor, gave Democrats a short-lived comeback in the South, winning every state in the old Confederacy except for Virginia, which was narrowly lost. However, in his unsuccessful 1980 re-election bid, the only Southern states he won were his native state of Georgia, West Virginia, and Maryland. The year 1976 was the last year a Democratic presidential candidate won a majority of Southern electoral votes. The Republicans took all the region's electoral votes in the 1984 election and every state except West Virginia in 1988.

In the 1992 election and 1996, when the Democratic ticket consisted of two Southerners (Bill Clinton and Al Gore), the Democrats and Republicans split the region. In both elections, Clinton won Arkansas, Louisiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia, Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware, while the Republican won Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Oklahoma. Bill Clinton won Georgia in 1992, but lost it in 1996 to Bob Dole. Conversely, Clinton lost Florida in 1992 to George Bush, but won it in 1996.

In 2000, however, Gore received no electoral votes from the South, even from his home state of Tennessee, apart from heavily urbanized and uncontested Maryland and Delaware. The popular vote in Florida was extraordinarily close in awarding the state's electoral votes to George W. Bush. This pattern continued in the 2004 election; the Democratic ticket of John Kerry and John Edwards received no electoral votes from the South apart from Maryland and Delaware, even though Edwards was from North Carolina, and was born in South Carolina. However, in the 2008 election, as many areas in the South became more urbanized, liberal, and demographically diverse, Barack Obama won the former Republican strongholds of Virginia and North Carolina as well as Florida; Obama won Virginia and Florida again in 2012 and lost North Carolina by only 2.04 percent. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won only Virginia while narrowly losing Florida and North Carolina. In 2020, Joe Biden won Virginia, a growing stronghold for Democrats, and narrowly won Georgia, in large part due to the rapidly growing Atlanta metropolitan area, while narrowly losing Florida and North Carolina.

While the South was shifting from the Democrats to the Republicans, the Northeastern United States went the other way. The Northeastern United States is defined by the US Census Bureau as Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and the New England States. Well into the 1980s, much of the Northeast – in particular the heavily suburbanized states of New Jersey and Connecticut, and the rural states of northern New England – were strongholds of the Republican Party. The Democratic Party made steady gains there, however, and from 1992 through 2012, all nine Northeastern states, from New Jersey to Maine, voted Democratic, with the exception of New Hampshire's plurality for George W. Bush in 2000.

2010 to present

Although Republicans gradually began doing better in presidential elections in the South starting in 1952, Republicans did not finish taking over Southern politics at the nonpresidential level until the elections of November 2010. As of 2023, the South is dominated by Republicans at both the state and presidential level, with Republicans controlling 21 of the 22 legislative bodies in the former Confederacy, the sole exception being the Virginia Senate. Between the defeats of Georgia Representative John Barrow, Arkansas Senator Mark Pryor and Louisiana Senator Mary Landrieu in 2014 and the election of Alabama Senator Doug Jones in 2017, there were no white Democratic members of Congress from the states that voted for George Wallace in 1968. Until November 2010, Democrats had a majority in the Alabama, North Carolina, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana Legislatures, a majority in the Kentucky House of Representatives and Virginia Senate, a near majority of the Tennessee House of Representatives, and a majority of the U.S. House delegations from Arkansas, North Carolina, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, as well as near-even splits of the Georgia and Alabama U.S. House delegations.

However, during the 2010 midterm elections, Republicans swept the South, successfully reelecting every Senate incumbent, electing freshmen Marco Rubio in Florida and Rand Paul in Kentucky, and defeating Democratic incumbent Blanche Lincoln in Arkansas for a seat now held by John Boozman. In the House, Republicans reelected every incumbent except for Joseph Cao of New Orleans, defeated several Democratic incumbents, and gained a number of Democratic-held open seats. They won the majority in the congressional delegations of every Southern state. Most Solid South states, with the exceptions of Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia, also elected or reelected Republicans governors. Most significantly, Republicans took control of both houses of the Alabama and North Carolina State Legislatures for the first time since Reconstruction, with Mississippi and Louisiana flipping a year later during their off-year elections. Even in Arkansas, the GOP won three of six statewide down-ballot positions for which they had often not fielded candidates until recently; they also went from eight to 15 out of 35 seats in the state senate and from 28 to 45 out of 100 in the State House of Representatives.

In 2012, the Republicans finally took control of the Arkansas State Legislature and the North Carolina Governorship, leaving West Virginia as the last Solid South state with the Democrats still in control of the state legislature, as well as the governorship. In 2014, though, both houses of the West Virginia legislature were finally taken by the GOP, and most other legislative chambers in the South up for election that year saw increased GOP gains. Arkansas' governorship finally flipped GOP in 2014 when incumbent Mike Beebe was term-limited, as did every other statewide office not previously held by the Republicans. Many analysts believe the so-called "Southern Strategy" that has been employed by Republicans since the 1960s is now virtually complete, with Republicans in firm, almost total, control of political offices in the South. However, the Louisiana governorship was won by John Bel Edwards in 2015, and Jim Hood won a fourth term as Mississippi Attorney General the same year, making them the only Southern Democratic statewide executive officials. Hood retired in 2019 to mount an unsuccessful run for Governor of Mississippi, and was succeeded by Republican Lynn Fitch, while Edwards was reelected as Governor of Louisiana.

The biggest exception to this trend has been the state of Virginia. It got an earlier start in the trend towards the Republican Party than the rest of the region. It voted Republican for president in 13 of the 14 elections between 1952 and 2004, while no other Southern state did so more than nine times (that state, Florida, is the other potential exception to the trend, but to a significantly lesser extent). Moreover, it had a Republican Governor more often than not between 1970 and 2002, and Republicans held at least half the seats in the Virginia congressional delegation from 1968 to 1990 (although the Democrats had a narrow minority throughout the 1990s), while with single-term exceptions (Alabama from 1965 to 1967, Tennessee from 1973 to 1975, and South Carolina from 1981 to 1983) and the exception of Florida (which had its delegation turn majority Republican in 1989), Democrats held at least half the seats in the delegations of the rest of the Southern states until the Republican Revolution of 1994. However, thanks in large part to massive population growth in Northern Virginia and the orientation of that population with the political ideologies of the solidly Democratic Northeast, the Democratic Party has won most statewide races since 2005, and, in the 2020 presidential election, carried the state by a double digit margin for the first time since 1944.[42]

Solid South in presidential elections

While Republicans occasionally won southern states in elections in which they won the presidency in the Solid South, it was not until 1960 that a Republican carried one of these states while losing the national election. As such, these states remained a key component of the Democratic coalition until that election.

| Democratic Party nominee |

| Republican Party nominee |

| Third-party nominee or write-in candidate |

Bold denotes candidates elected as president

Solid South in gubernatorial elections

Officials who acted as governor for less than ninety days are excluded from this chart. This chart is intended to be a visual exposition of party strength in the solid south and the dates listed are not exactly precise. Governors not elected in their own right are listed in italics.

The parties are as follows: Democratic (D), Farmers' Alliance (FA), Prohibition (P), Readjuster (RA), Republican (R).

See also

Notes

- Despite the South's excessive representation relative to voting population, the Great Migration did cause Mississippi to lose Congressional districts following the 1930 and 1950 Censuses, whilst South Carolina and Alabama also lost Congressional seats after the former Census and Arkansas following the latter.

- Electoral votes awarded by the Electoral Commission

- Oklahoma was not a state until 1907 and did not vote in presidential elections until 1908

- One of Tennessee's electoral votes went to Strom Thurmond.

- One of Alabama's electoral votes went to Walter B. Jones.

- Five of Alabama's electoral votes went to John F. Kennedy.

- One of Oklahoma's electoral votes went to Harry F. Byrd.

- One North Carolina Republican elector switched his vote to Wallace.

- One Virginia Republican elector switched his vote to John Hospers.

- One West Virginia Democratic elector switched her vote to Lloyd Bentsen.

- One Texas Republican elector switched their vote to John Kasich, and another cast his vote for Ron Paul.

- Since both the Governor and Lieutenant Governor had been impeached, the former resigning and the latter being removed from office, Stone, as president of the Senate, was next in line for the governorship. Filled unexpired term and was later elected in his own right.

- As lieutenant governor, filled unexpired term.

- Died in office.

- Resigned upon appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury.

- Did not run for re-election in 1888, but due to the election's being disputed, remained in office until February 6, 1890.

- Elected in 1888 for a term beginning in 1891, an election dispute prevented Fleming from taking office until February 6, 1890

- William S. Taylor (R) was sworn in and assumed office, but the state legislature challenged the validity of his election, claiming ballot fraud. William Goebel (D), his challenger in the election, was shot on January 30, 1900. The next day, the legislature named Goebel governor. However, Goebel died from his wounds three days later.

- As lieutenant governor, acted as governor for unexpired term and was subsequently elected in his own right.

- As President of the state Senate, filled unexpired term and was subsequently elected in his own right.

- Gubernatorial terms were increased from two to four years during Jelks' governorship; his first term was filling out Samford's two-year term, and he was elected in 1902 for a four-year term.

- Resigned to take an elected seat in the United States Senate. March 21, 1905

- As Speaker of the Senate, ascended to the governorship.

- The elected governor, Hoke Smith, resigned to take his elected seat in the United States Senate. John M. Slaton, president of the senate, served as acting governor until Joseph M. Brown was elected governor in a special election.

- The elected Governor, Joseph Taylor Robinson, resigned on March 8, 1913 to take an elected seat in the United States Senate. President of the state Senate William Kavanaugh Oldham acted as governor for six days before a new Senate President was elected. Junius Marion Futrell, as the new president of the senate, acted as governor until a special election.

- Elected in a special election.

- Resigned on the initiation of impeachment proceedings. Aug. 25, 1917.

- Resigned to take an elected seat in the United States Senate.

- Impeached and removed from office. November 19, 1923

- Died in his third term of office. October 2, 1927.

- Resigned to be a judge on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas.

- Impeached and removed from office. March 21, 1929

- As Speaker of the Senate, ascended to the governorship. Subsequently elected for two full terms.

- Paul N. Cyr was lieutenant governor under Huey Long and stated that he would succeed Long when Long left for the Senate, but Long demanded Cyr forfeit his office. King, as president of the state Senate, was elevated to lieutenant governor and later governor.

- Resigned to take an appointed seat in the United States Senate.

- Resigned upon victory in the Democratic primary for the United States Senate, August 4, 1941.

- Died in office. July 11, 1949

- As President of the state Senate, filled unexpired term.

- Resigned upon election to the Presidency of the United States.

- Removed from office upon being convicted of illegally using campaign and inaugural funds to pay personal debts; he was later pardoned by the state parole board based on innocence.

- Elected as a Democrat in 1987 but switched to Republican in 1991.

- Resigned after being convicted of mail fraud in the Whitewater scandal.

- Resigned to take an elected seat in the U.S. Senate. November 15, 2010

- Elected as a Republican, Crist switched his registration to independent in April 2010.

- Resigned April 10, 2017.

- As president of the Senate, served as acting governor until he won a special election in 2011.

- As Lieutenant Governor, succeeded to governorship upon resignation of Robert Bentley on April 10, 2017.

- Elected as a Democrat, Justice switched his registration to Republican in August 2017.

References

- Dewey W. Grantham, The Life and Death of the Solid South: A Political History (1992).

- "US Census Region Map" (PDF).

- Jordan, David M. (1988). Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier's Life. Indiana University Press. p. 305.

- "Archives of Maryland Historical List: Constitutional Convention, 1864". November 1, 1864. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- "Missouri abolishes slavery". January 11, 1865. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- "Tennessee State Convention: Slavery Declared Forever Abolished". NY Times. January 14, 1865. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- "On this day: 1865-FEB-03". Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- "Slavery in Delaware". Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- Lowell Hayes Harrison and James C. Klotter (1997). A new history of Kentucky. p. 180. ISBN 978-0813126210. In 1866, Kentucky refused to ratify the 13th Amendment. It did ratify it in 1976.

- George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (1984), p. 132

- Gordon B. McKinney, Southern Mountain Republicans, 1865–1900: Politics and the Appalachian Community (1998)

- C. Van Woodward, The Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 (1951) pp 235–90

- Valelly, Richard M. (October 2, 2009). The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226845272 – via Google Books.

- Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p.10, Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Glenn Feldman, The Disenfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- Michael Perman.Struggle for Mastery: Disenfranchisement (sic) in the South, 1888–1908 (2001), Introduction

- Jeffery A. Jenkins, Justin Peck, and Vesla M. Weaver. "Between Reconstructions: Congressional Action on Civil Rights, 1891–1940." Studies in American Political Development 24#1 (2010): 57–89. online

- Connie Rice: Top 10 Election Myths to Get Rid Of : NPR The situation in Louisiana was an example—see John N. Pharr, Regular Democratic Organization#Reconstruction and aftermath, and the note to Murphy J. Foster (who served as governor of Louisiana from 1892 to 1900).

- Presidential election of 1900 – Map by Counties (and subsequent years)

- Sullivan, Robert David; ‘How the Red and Blue Map Evolved Over the Past Century’; America Magazine in The National Catholic Review; June 29, 2016

- Kari A. Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968 (2001).

- "Moving Ahead: What Election 2016 Meant for State Legislatures".

- Foner, Eric, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, Harper Collins, 2002, p. 38

- Snell, Mark A., West Virginia and the Civil War. History Press, 2011, p. 28

- Bastress, Robert M., The West Virginia State Constitution, Oxford Univ. Press, 2011, p. 21

- Ambler, Charles Henry, A History of West Virginia, Prentice-Hall, 1937, p. 376.

- Williams, John Alexander, West Virginia, a History, W. W. Norton, 1984, p. 94

- Herbert, Hilary Abner Why the Solid South? Or, Reconstruction and Its Results, R. H. Woodward, 1890, pp. 258–284

- Tumulty, Karen (26 October 2013). "A Blue State's Road to Red". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Woodruff, Betsy (29 October 2014). "Goodbye West Virginia". Slate. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Dawson, Marion L.,Will the South Be Solid Again?, The North American Review, Volume 164, 1897, pp. 193–198

- "Too Close to Call: Presidential Electors and Elections in Maryland featuring the Presidential Election of 1904". msa.maryland.gov.

- Second Thoughts: Reflections on the Great Society New Perspectives Quarterly, Winter 1987

- Kuziemko, Ilyana; Washington, Ebonya (November 1, 2015). "Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate". Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w21703. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Nation: Spiro Agnew: The King's Taster". Time. 1969-11-14. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2021-10-17.

- Johnson, Thomas A. (August 13, 1968). "Negro Leaders See Bias in Call of Nixon for 'Law and Order'". The New York Times. p. 27. Retrieved 2008-08-02.(subscription required)

- Greenberg, David (November 20, 2007). "Dog-Whistling Dixie: When Reagan said 'states' rights', he was talking about race". Slate. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012.

- "Nixon in Dixie", The American Conservative magazine

- Ted Van Dyk. "How the Election of 1968 Reshaped the Democratic Party", Wall Street Journal, 2008

- Childs, Marquis (June 8, 1970). "Wallace's Victory Weakens Nixon's Southern Strategy". The Morning Record.

- Hart, Jeffrey (2006-02-09). The Making of the American Conservative Mind (television). Hanover, New Hampshire: C-SPAN.

- Farnswoth, Stephen; Hanna, Stephen (16 November 2012). "Why Virginia's purple is starting to look rather blue". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "1996 Presidential General Election Results - Mississippi".

Further reading

- Feldman, Glenn (2015). The Great Melding: War, the Dixiecrat Rebellion, and the Southern Model for America's New Conservatism. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- Feldman, Glenn (2013). The Irony of the Solid South: Democrats, Republicans, and Race, 1864-1944. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- Frederickson, Kari A. (2001). The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Grantham, Dewey W. (1992). The Life and Death of the Solid South. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

- Herbert, Hilary A., et al. (1890). Why the Solid South? Or, Reconstruction and Its Results. Baltimore, MD: R. H. Woodward & Co.

- Sabato, Larry (1977). The Democratic Party Primary in Virginia: Tantamount to Election No Longer. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.