Spaniards in Venezuela

Spaniards or Spanish people in Venezuela, are persons of fully Spanish or Iberian ancestry or those who have the Spanish Citizenship and are residing in Venezuela. Most of Spaniards in Venezuela are in Venezuela because of Spanish immigration to Venezuela, Spanish Civil War, Business, Related people and another circunstancies. However, the great wave of Spaniards occurred in the 19th century, the first time Spanish exiles arrived for political reasons after the Spanish Civil War, and the second was the largest since the late 1950s. The forties and throughout the fifties were driven by the severe economic difficulties Spain experienced in those years. The latest figures recorded by Spanish consulates show 207,692 registered Spaniards. But the true immigrant figure is estimated to be higher because many Spaniards have not renewed their documents or have lost their citizenship and have not yet decided to regain it.[2]

Españoles en Venezuela | |

|---|---|

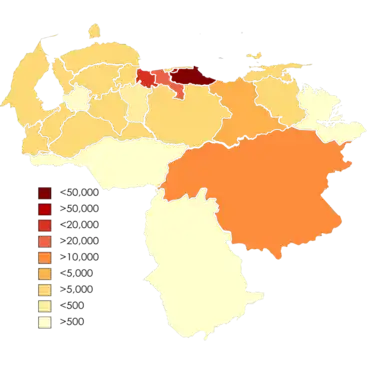

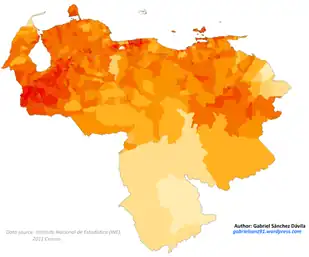

Map showing the Spanish Diaspora in the States of Venezuela | |

| Total population | |

| 231,833[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish, Galician, Catalan, Valencian and local dialects | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Venezuelans of European descent |

History

During the 19th century, various immigration plans had been projected in Venezuela that had little impact despite the efforts made to that end. The situation changed substantially starting in 1936 when interest in promoting immigration grew, as recognized by President Eleazar López Contreras when he raised the urgent need to populate the Venezuelan territory, for which the contribution of immigrants who could contribute to the prosperity of the country. Precisely in that same year, the Civil War broke out in Spain, which led to the emigration of thousands of people who sought refuge in the Americas, fleeing the atrocities of the Franco regime. This was the first wave of Spanish immigrants whose motivations for leaving their land were political. The second wave was recorded from 1948 and was more due to economic problems due to the hardships that the population was going through, as a consequence of the devastation caused by the Civil War.

Since 1939, an increasingly large community of Spanish immigrants began to enter Venezuela, initially occupying in most cases low-skill jobs, to later move up in their jobs, or venture to create businesses on their own. many of which would become in the course of a few years successful companies that have represented a significant contribution to the advancement of the Venezuelan economy. Reconstructing the insertion process of Spanish immigrants in Venezuela is the objective of this article in which immigration promotion policies are analyzed since the second half of the 1930s and the development of agricultural colonies and other economic activities. Finally, reference is made to a series of representative cases of this migratory flow that allows outlining a significant dimension of business history in Venezuela.

Early Immigration

Tragic events rocked the European scene in the course of the 1930s. Added to the deep economic depression was the impetuous advance of totalitarian tendencies whose clearest expression was found in fascism and Nazism. Likewise, the Soviet Union was in the process of becoming a hegemonic power in Eastern Europe, and intended to extend its range of action to the Western world. These political currents fed and sharpened the rivalries and conflicts that arose in Spain as a result of the establishment of the Republic, a context in which the political agitation was gaining more intensity day after day until it led to the Civil War that broke out in 1936, at the end of which he enthroned a dictatorial regime that remained in power for more than three decades.

In addition to the material destruction as a result of the conflict and the obstacles to rebuilding the Spanish economy due to World War II, in the postwar years the decision of the European nations and the United States to declare a blockade against that nation was added.

| Part of a series on the |

| Spanish people |

|---|

_alternate_colours.svg.png.webp) Rojigualda (historical Spanish flag) |

| Regional groups |

Other groups

|

| Significant Spanish diaspora |

| Languages |

|

Other languages |

|

|

that it was subjected to Franco's tyranny. The consequence was the aggravation of scarcity and misery, which pushed thousands and thousands of Spaniards to seek new horizons to start their lives over. At that time, the Americas offered many possibilities for that population that yearned to obtain a productive job and consolidate family ties.

Meanwhile, Venezuela was in full political transition after the conclusion of 27 years of the dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez. In the midst of this environment in which the air of renewal was breathed, projects aimed at the development of agriculture and industry began to be designed with a view to materialising economic and institutional modernisation.

The greatest concern of Alberto Adriani, in charge of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock in the first months of 1936 and later of the Treasury office, was aimed at achieving the expansion of agriculture and the entry of immigrants to undertake productive work in the country. In this vast territory it was necessary to have a suitable workforce to engage in agriculture. An important milestone was the creation in 1936 of the Mendoza agricultural colony, located near Ocumare del Tuy (Miranda), where around 30 Spanish families stayed the following year.

Arturo Uslar Pietri described the issue of immigration as crucial if agriculture was to be promoted, which was in a state of prostration as a consequence of the effects of the Great Depression and also of structural deficiencies originating mostly from problems originating from the previous century. In Uslar's opinion, Venezuela had a small population in a vast area and, as an aggravating circumstance, it lacked communication routes, its market was narrow and the workforce was insufficient. Therefore, the promotion of immigration required precise plans to define the way in which this population would be attracted and its progressive integration into national life. One priority was to organize small agricultural farms, an initiative that would be very useful for the creation of "permanent" wealth that could replace the central role of oil in the future. The immigration programs had to be part of a vast plan to transform the national economy that required a study and selection of the most appropriate type of immigration and the preparation of an inventory of areas and lands suitable for agriculture, soil conditions, the weather, markets and possible crops. Another highly relevant aspect was linked to the integration of immigrants, for which purpose it was necessary to provide for their provisional residence in a hotel, to later transfer them to agricultural colonies and ensure the provision of implements, seeds, land, housing, technical assistance and credit help. All these points were raised by Arturo Uslar Pietri as part of his famous idea of "sowing oil".

Distribution

Within the framework of the plans drawn up from 1936, important institutional reforms took place. On 26 August 1938, the foundation of the Technical Institute for Immigration and Colonization (ITIC) was decreed, directed between March and July 1939 by Arturo Uslar Pietri.

In the decree of creation of the ITIC it was indicated that its mission consisted of the implantation of agricultural colonies by means of the acquisition of lands of private property in determined regions. For this purpose, the Institute had to design a general colonization plan guaranteeing maximum efficiency in the exploitation and division of the available land, with the objective of obtaining high yields taking into account the soil conditions, the working capacity of the families there settled and the capital that they could possess or obtain.

In 1937, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock bought 2,800 hectares in the Chirgua Valley (Carabobo) that would be used to form a model colony. The site had a long tradition, since it had belonged to a family related to Simón Bolívar. There existed in colonial times a cane farm with a sugar mill, which in later decades was occupied by a coffee farm. The colony began with the construction of 100 houses and the installation of the corresponding basic services. In 1938, the selection of 75 Swiss and Danish families was carried out, of which only 48 families of the latter nationality arrived, although between March and June of the following year the majority of the inhabitants of that origin were re-embarked to their country of origin. At the beginning of the 1940s, around 350 people lived in said colony, grouped into 35 Spanish families, 20 Venezuelans, 8 Danish, 4 Portuguese and one Cuban.

In the Portuguesa state, the Guanare neighborhood was established in 1939, where immigrants of Portuguese origin settled at first, and later 12 Spanish families. In the state of Táchira, the Colonia Rubio was established in 1940 with 40 Spanish families and in that same year the colony La Guayabita in Turmero (Aragua), where 7 families from the same origin stayed.

At that time, great interest arose in receiving Basque immigrants, taking into consideration that they would be professionals who could contribute to Venezuelan development. One of the most forceful voices in favor of the Basques was that of Simón Gonzalo Salas, who wrote a pamphlet in 1938 expressing his support for these immigrants. He considered that at that time there were around 80,000 exiled Basques in French Third Republic who were waiting for an authorization to move to Venezuela. In the pamphlet he assumed the defense of the Basques who had been disqualified by his political opinions. In this regard, he stated that they did not have extremist ideas and that they would not pose any threat to Venezuela because they were "orphans of their own Homeland", for being in exile in France after having fought for the republican cause. This position was shared by Uslar Pietri, who also supported the negotiations for the entry of Basques into the country.

The Venezuelan legation in France, since 1938, took care of establishing agreements to admit the entry of Basque refugees, especially if they were linked to construction. Precisely, in March 1939 an agreement was signed with the government of Euskadi, exiled in France and controlled by the Basque Nationalist Party, authorizing the transfer of a group to Venezuela, whose members would receive work contracts. In the middle of that year, the trip of 274 refugees was arranged, including university professionals, builders, designers and draftsmen

Despite the fact that maritime traffic suffered a virtual paralysis in the war years, according to ministerial data, spontaneous immigration increased by 38% between 1939 and 1940 and "directed" immigration registered an increase of 61% in those same years. years. Among the new arrivals in 1940, 34% were made up of farmers, 24% by liberal professions, and 42% by specialized workers

Society and economy of Venezuela

The serious situation that Spain was going through as a result of the Civil War coincided with a stage of profound transformations in Venezuelan society, one of whose expressions was the adoption of active policies to attract the foreign population. In this way, immigration became a fundamental strategy aimed at achieving the incorporation of labor and technical knowledge for the progress of agriculture and industry. Likewise, the entry of professionals and specialized workers who could contribute to the development of infrastructure and construction works, and also to the advancement of education and health was expected. Precisely, "directed" or selective immigration was nurtured in a first stage by the thousands of Spanish refugees who were trying to leave Europe.

The situation changed in the following decade, when the "open door" policy for immigrants was put into practice, which increased the number of entries, mainly from residents from the Canary Islands and Galicia, forced to leave their land. for economic reasons. Although the largest percentage of this migratory flow tended to remain in urban centers, another significant proportion went to the interior of the republic, where they established farms that resulted in the renewal of cultivation methods and techniques. As part of a broader process, along with agricultural activity, a modern commercial system for the distribution of farm products developed, which gave rise to an extensive network that allowed linking regional spaces, previously disjointed, and satisfying the demand for foods. While the greater yield of agriculture and the growing efficiency of commerce and banking services complemented each other, the internal market was expanding, giving rise to the expansion of industry, whose varied production was increasingly based on technological advances. These dimensions of national economic life had the laborious and persevering participation of Spanish immigration, from the bottom rungs to the highest positions.

The development of these companies was part of the extraordinary dynamism that the Venezuelan economy had acquired thanks to the constant increase in oil income. Frequently they were family businesses, whose administration was later left in the hands of the descendants, even when in several cases the companies were absorbed by large and modern corporations, typical of these times of globalization.[3]

Demographics

As of December 2014, there are more 231,833 Spanish citizens in Venezuela.[4] Most Venezuelans in Spain have Spanish nationality.[5]

A total of 112 Spanish centers and institutions are operating in Venezuela, with which the Ministry maintains permanent contact. These become collaborators to bring our services closer, especially to Spaniards who live in the most remote areas of our headquarters in the capital.

The following table indicates the number of Spanish residents by state as well as the number of welfare pensioners.

| States of Venezuela | Spanish Residents | Welfare pensioners |

|---|---|---|

| Amazonas | 67 | 0 |

| Anzoátegui | 6.679 | 73 |

| Apure | 146 | 8 |

| Aragua | 13.825 | 259 |

| Barinas | 1.274 | 19 |

| Bolívar | 5.218 | 59 |

| Carabobo | 19.669 | 358 |

| Cojedes | 676 | 27 |

| Delta Amacuro | 94 | 1 |

| Distrito Capital | 44.201 | 852 |

| Falcón | 2.372 | 42 |

| Guárico | 2.091 | 85 |

| Lara | 9.402 | 293 |

| Mérida | 2.411 | 40 |

| Miranda | 72.923 | 688 |

| Monagas | 1.670 | 23 |

| Nueva Esparta | 3.480 | 41 |

| Portuguesa | 2.709 | 71 |

| Sucre | 1.626 | 35 |

| Táchira | 1.858 | 10 |

| Trujillo | 508 | 7 |

| Vargas | 4.429 | 127 |

| Yaracuy | 2.372 | 110 |

| Zulia | 5.721 | 47 |

| Non-Constation | 786 | 0 |

| Disenrolled for not being registered in the Electoral Census | 25.626 | 0 |

| Total | 231.833 | 3.275 |

The number of beneficiaries of the Need Benefit in the last payroll of 2014 (fourth quarter) amounts to 3,214, distributed by Autonomous Communities:

| Autonomy Community | Amount of Beneficiares |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | 72 |

| Aragon | 17 |

| Canarias | 1.901 |

| Cantabria | 19 |

| Castilla la Mancha | 27 |

| Castile and León | 74 |

| Catalonia | 93 |

| Ceuta | 2 |

| Madrid Community | 64 |

| Foral Navarra Community | 6 |

| Valencia | 33 |

| Region of Murcia | 6 |

| Extremadura | 9 |

| Galicia | 686 |

| Balearic Islands | 7 |

| La Rioja | 4 |

| Melilla | 4 |

| Basque Country | 59 |

| Asturias | 115 |

| External (Not born in Spain) | 16 |

| Total | 3.214 |

References

- "Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social". www.mites.gob.es. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- "Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social". www.mites.gob.es. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Banko, Catalina (2019). "La inmigración española en Venezuela: una experiencia de esfuerzo y trabajo productivo". Espacio Abierto (in Spanish). 28 (1): 123–137.

- "Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social". www.mites.gob.es. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Rodríguez, Diego Fonseca (17 March 2016). "Los españoles en el extranjero aumentan un 56,6% desde 2009". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- "Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social". www.mites.gob.es. Retrieved 19 December 2022.