Spanish poetry

Medieval Spain

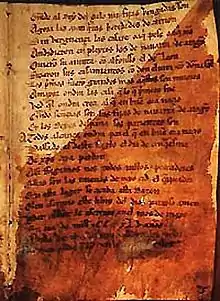

The Medieval period covers 400 years of different poetry texts and can be broken up into five categories.

Primitive lyrics

Since the findings of the Kharjas, which are mainly two, three, or four verses, Spanish lyrics, which are written in Mozarabic dialect, are perhaps the oldest of Romance Europe. The Mozarabic dialect has Latin origins with a combination of Arabic and Hebrew fonts.[1]

The epic

Many parts of Cantar de Mio Cid, Cantar de Roncesvalles, and Mocedades de Rodrigo are part of the epic. The exact portion of each of these works is disputed among scholars. The Minstrels, over the course of the 12th to the 14th centuries, were driving force of this movement. The Spanish epic likely emanated from France. There are also indications of Arabic and Visigoth. It is usually written in series of seven to eight syllables within rhyming verse.[2]

Mester de clerecía

The cuaderna vía is the most distinctive verse written in Alexandrine verse, consisting of 12 syllables. Works during the 13th century include religious, epics, historical, advice or knowledge, and adventure themes. Examples of such themes include The Miracles of the Virgin Mary, Poema de Fernán González, Book of Alexander, Cato’s Examples, and Book of Apolonio, respectively. Some works vary and are not necessarily mester de clerecía, but are reflective of it. Such poems are of a discussion nature, such as Elena y María and Reason to Love. Hagiographic poems include Life of St. María Egipciaca and Book of the Three Wise Men. Mature works, like The Book of Good Love and Rhyming Book of the Palace, were not included in the genre until the 14th century.[3]

Collection of verse (Cancionero)

During this movement, language use went from Galician-Portuguese to Castilian. Octosyllable, twelve syllables, and verse of arte mayor were becoming the footing of verses. Main themes derive from Provençal poetry. This form of poetry was generally compilations of verses formed into books, also known as cancioneros. Main works include Cancionero de Baena, Cancionero de Estuniga, and Cancionero General. Other important works from this era include parts of Dance of Death, Dialogue Between Love and an Old Man, verses of Mingo Revulgo, and verses of the Baker Woman.[4]

Spanish ballads

The romanceros have no set number of octosyllables, but these poems are only parallel in this form. Romancero Viejo consists of the oldest poems in these epochs, which are anonymous. The largest amount of romances comes from the 16th century, although early works were from the 14th century. Many musicians of Spain used these poems in their pieces throughout the Renaissance. Cut offs, archaic speech, and recurrent dialogue are common characteristics among these poems; however the type and focus were diverse. Lyrical romances are also a sizeable part of this era. During the 17th century, they were recycled and renewed. Some authors still stayed consistent with the original format. By the 20th century, the tradition still continued.[5]

Early Middle Ages

- Mozarab Jarchas, the first expression of Spanish poetry, in Mozárabe dialect

- Mester de Juglaría

- Mester de Clerecía

- Troubadours

- Xohán de Cangas

- Palla (troubadour)

- Paio Soares de Taveirós

Later Middle Ages

Arabic and Hebrew poetry during the Moorish period

During the time when Spain was occupied by the Arabs after the early 8th century, the Iberian Peninsula was influenced by the Arabic language in both the central and southern regions. Latin still prevailed in the north.[6] The Jewish culture had its own Golden Age through the span of the 10th to 12th centuries in Spain. Hebrew poetry was usually in the style of Piyyut; however, under Muslim rule in Spain, the style changed. These poets began to write again in what was the "pure language of the Bible". Beforehand, poems were written in Midrash. This change was a result of the commitment the Arabs had to the Koran. Tempos and secular topics were now prevalent in Hebrew poetry. However, these poems were only reflections of events seen by the Jews and not of ones practiced themselves.[7]

After 1492

The Golden Age (El Siglo de Oro)

This epoch includes the Renaissance of the 16th century and the Baroque of the 17th century.[8] During the Renaissance, poetry became partitioned into culteranismo and conceptismo, which essentially became rivals.

- Culteranismo used bleak language and hyperbaton. These works largely included neologisms and mythological topics. Such characteristics made this form of poetry highly complex, making comprehension difficult.

- Conceptismo was a trend using new components and resources. An example of this new extension was the Germanias. Works included comparative and complex sentences. This movement derived from Petrarchanism.

During the Baroque period, Satire, Neostoicism, and Mythological themes were also prevalent.

- Satire tended to be directed to the elites, criticizing the defects of the society. This form of poetry often resulted in severe punishments being administered to the poets.

- Neostoicism became a movement of philosophical poetry. Ideas from the medieval period resurfaced.

- Mythological themes were more common in culteranismo. Not until the Generation of 1927 did these poems gain more importance. La Fábula de Polifemo y Galatea and Las Soledades are two key works.[9]

Romanticism

Germany and England were the large forces in this movement. Over the course of the late 18th century to the late 19th century, Romanticism spread philosophy and art through Western societies of the world. The earlier part of this movement overlapped with the Age of Revolutions. The idea of the creative imagination was rising above the idea of reason. Minute elements of nature, such as bugs and pebbles, were considered divine. There were many variations of the perception of nature in these works. Instead of allegory, this era moved towards myths and symbols. The power of human emotion emerged during this period.[10]

1898 until 1926

Spain went through drastic changes after the demise of Spain’s colonial empire. French and German inspiration along with Modernism greatly improved the culture of Spain with the works of the Generation of 1898, which were mostly novelists but some were poets.[11]

1927 until 1936

The Generation of 1927 were mostly poets. Many were also involved with the production of music and theatre plays.

- Rafael Alberti

- Vicente Aleixandre

- Dámaso Alonso

- Manuel Altolaguirre

- Luis Cernuda

- Gerardo Diego

- Manuel de Falla; influential on poets, for his vision of Moorish Spain

- Juan Ramón Jiménez

- Federico García Lorca

- Jorge Guillen

- Emilio Prados

- Pedro Salinas

1939 until 1975

Poets during the World War II and under General Franco in peacetime:

- Juan Ramón Jiménez received the Nobel Prize in Literature 1956, "For his lyrical poetry, which in Spanish language constitutes an example of high spirit and artistical purity." Was the last survivor of Generation of 1898. During the mid-20th century, works steadily moved back to literary and political aspects.[12]

- Gabriela Mistral

- Nicanor Parra

- Alejandra Pizarnik

- Luis Buñuel

- Ángel Crespo

- Jaime Gil de Biedma

- Carlos Edmundo de Ory

- León Felipe

- Ángel González Muñiz

- Miguel Hernández

- José Hierro

- Lluis Llach

- Leopoldo Panero

- José María Pemán

1975 until present

These works became experimental, using themes, styles and characteristics of traditional poetry throughout Spain’s time and combining them with current movements. Some poets remain more traditional, while others more contemporary.

Post-Franco and Contemporary Spanish Poets:

- Blanca Andreu

- Miguel Argaya

- María Victoria Atencia

- Felipe Benítez Reyes

- Carlos Bousoño

- Giannina Braschi

- Francisco Brines

- José Manuel Caballero Bonald

- Matilde Camus

- Luisa Castro

- Antonio Colinas

- Isla Correyero

- Aurora de Albornoz

- Luis Alberto de Cuenca

- Francisco Domene

- Rafael Pérez Estrada

- José María Fonollosa

- Gloria Fuertes

- Vicente Gallego

- Antonio Gamoneda

- Enrique García-Máiquez

- José Agustín Goytisolo

- Félix Grande

- Clara Janés

- Diego Jesús Jiménez

- Chantal Maillard

- Antonio Martínez Sarrión

- Carlos Marzal

- Bruno Mesa

- Juan Carlos Mestre

- Luis García Montero

- Luis Javier Moreno

- Lorenzo Oliván

- Leopoldo María Panero

- Francisco Pino

- Juan Vicente Nuevo Piqueras

- Claudio Rodríguez

- Ana Rossetti

- Ángel Rupérez

- Elvira Sastre

- Jaime Siles

- Jenaro Talens

- Andrés Trapiello

- José Miguel Ullán

- José Ángel Valente

- Álvaro Valverde

- Luis Antonio de Villena

See also

References

- "PRIMITIVE LYRICS". www.spanisharts.com.

- "THE EPIC". www.spanisharts.com.

- "MESTER DE CLERECÍA". www.spanisharts.com.

- "CANCIONERO". www.spanisharts.com.

- "THE SPANISH BALLADS". www.spanisharts.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Poetry and History in Jewish Culture". Archived from the original on 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- "GOLDEN AGE POETRY". www.spanisharts.com.

- "Poetry in the Golden Age - Literature in Spain | donQuijote.org". Archived from the original on 2011-07-01. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- "Romanticism". Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- "Answers - The Most Trusted Place for Answering Life's Questions". Answers.

- "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1956". NobelPrize.org.

Further reading

- D. Gareth Walters. The Cambridge Introduction to Spanish Poetry: Spain & Spanish America. (2002).

- Linda Fish Compton. Andalusian Lyric poetry and Old Spanish Love Songs (1976) (includes translations of some of the medieval anthology of love poems, compiled by Ibn Sana al-Mulk, the Dar al-tiraz).

- Emilio Garcia Gomez. (Ed.) In Praise of Boys: Moorish Poems from Al-Andalus (1975).

- F. J. Gea Izquierdo. Antología esencial de la poesía española, Independently published. Alicante (2021).

- Paul Halsall has a bibliography online, listing journal articles in English on medieval poetry in Spain.

- Carmi, T. (Ed.) The Penguin Book of Hebrew Verse. New York: Penguin Books (1981). ISBN 0-14-042197-1 (includes translations of Judah Al-Harizi, Nahmanides, Todros Abulafia and other Jewish poets from Spain).

- A. Robert Lauer, University of Oklahoma, on Spanish Metrification: the common structures of Spanish verse