Liberty style

Liberty style (Italian: stile Liberty [ˈstiːle ˈliːberti]) was the Italian variant of Art Nouveau, which flourished between about 1890 and 1914. It was also sometimes known as stile floreale ("floral style"), arte nuova ("new art"), or stile moderno ("modern style"). It took its name from Arthur Lasenby Liberty and the store he founded in 1874 in London, Liberty Department Store, which specialized in importing ornaments, textiles and art objects from Japan and the Far East. Major Italian designers using the style included Ernesto Basile, Ettore De Maria Bergler, Vittorio Ducrot, Carlo Bugatti, Raimondo D'Aronco, Eugenio Quarti, and Galileo Chini.

.jpg.webp)  Top: Casa Galimberti by Giovanni Battista Bossi: Bottom: Cobra chair and writing desk by Carlo Bugatti | |

| Years active | c. 1890–1920 |

|---|---|

| Country | Italy |

Liberty style was especially popular in large cities outside of Rome (the capital) which were eager to establish a distinct cultural identity, particularly Milan, Palermo and Turin, the city where the first major exposition of the style in Italy was held in 1902. This marked a major event and featured works of both Italian designers and other Art Nouveau designers from around Europe.[1]

Liberty style, like other versions of Art Nouveau, had the ambition of turning ordinary objects, such as chairs and windows, into works of art. Unlike the French and Belgian Art Nouveau, based primarily on nature, Liberty style was more strongly influenced by the Baroque style, with very lavish ornament and color, both on the interior and exterior.[2] The Italian poet and critic Gabriele d'Annunzio wrote in 1889, as the style was just beginning, "the genial sensual debauche of the Baroque sensibility is one of the determining variants of the Italian Art Nouveau."[3]

Liberty style is considered to be a western offshoot of the 19th-century British Arts and Craft movement,[4] which was a response against the mechanization and dehumanizing of the artistic process.

Palermo in the late 1800s

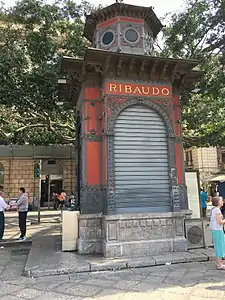

The first examples of the liberty style in Italy are found in Palermo, in particular Villa Favaloro, and in the large building of Teatro Massimo and in its square with kiosks in this style dating back to the end of the nineteenth century. In particular, two architects were the first representatives of this new style: Giovan Battista Filippo Basile and his son Ernesto Basile.

Liberty kiosk dating back to the early and 1900s, is located in Piazza Verdi in front of the Teatro Massimo in Palermo

Liberty kiosk dating back to the early and 1900s, is located in Piazza Verdi in front of the Teatro Massimo in Palermo Villa Favaloro was built in 1889 in liberty style by Giovan Battista Filippo Basile in Palermo

Villa Favaloro was built in 1889 in liberty style by Giovan Battista Filippo Basile in Palermo Villino Favaloro, Liberty decoration of the entrance door to the loggia, in Palermo

Villino Favaloro, Liberty decoration of the entrance door to the loggia, in Palermo

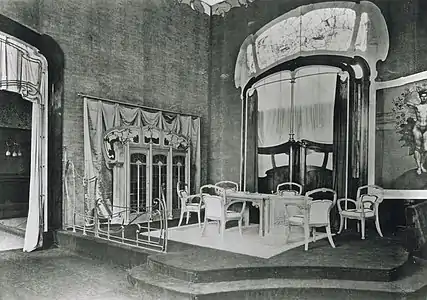

The 1902 Turin Exposition

The 1902 Turin Exposition, formally titled, Torino 1902: Le Arti Decorative Internazionali Del Nuovo Secolo, was the signature event of the style. It included designers from the United States, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, England, France, Holland, Norway, Austria, Scotland, Sweden and Hungary. Those displaying their works included Victor Horta, the pioneer Art Nouveau architect and furniture designer from Brussels. who displayed rooms with sets of furniture.

Postcard of the 1902 Turin Exposition

Postcard of the 1902 Turin Exposition Poster for the 1902 Turin Exposition by Leonardo Bistolfi (1902)

Poster for the 1902 Turin Exposition by Leonardo Bistolfi (1902) Art Nouveau furniture by Victor Horta displayed at Turin Exposition (1902)

Art Nouveau furniture by Victor Horta displayed at Turin Exposition (1902)

Furniture and interior design

The Liberty style in interior design and furniture had three distinct tendencies. The first was very floral and sculptural, following the model of England and France. The major designers in this style were Vittorio Valebrega and Agostino Lauro, and particularly the furniture manufacturer Valabrega, which produced works in series. A second tendency was more discrete, and was similar to designs of the British Arts and Crafts movement, with linear forms, simplicity, and artisanal quality. The major designers in this school were Ernesto Basile and Giacomo Cometti.[5]

The third tendency was for forms that were much more original and exotic, often derived from the styles of North Africa and the Middle East. These works were The most influential designer in this style was Carlo Bugatti, a member of a large family of artists and father of Ettore Bugatti, the automobile designer. His works first reached international attention at the 1902 Turin Exposition. His furniture was thoroughly original, having little or no reference to other European versions of Art Nouveau. He used an extremely wide range of materials in his furniture, including ivory and rare woods. He was particularly fond of the keyhole form. His cobra chair, was inspired by the chairs of African chieftains, and was made of tropical woods, painted parchment and hammered copper.[6]

Bugatti's theory was that any object, no matter what its function, could be transformed into a work of art. An unusual example of the theory that anything could be made into a work of art is the statue of dancing elephant by Rembrandt Bugatti, the son of Carlo Bugatti, in 1908. In 1928, in a version made of silver, it was turned into a radiator cap for the Bugatti Royale automobile.[6]

Another notable designer of Liberty style furniture was Eugenio Quarti, who had won a prize at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. He apprenticed in Paris and worked for a time in the studio of Carlo Bugatti, but soon departed from Bugatti's exoticism and worked in a more classical style. He used traditional fine woods, such as mahogany and walnut, combined with inlays of ivory, and brass, glass, and other modern elements.[7]

Cupboard by Carlo Bugatti (1895)

Cupboard by Carlo Bugatti (1895) Cobra Chair by Carlo Bugatti (1902) (Musée D'Orsay)

Cobra Chair by Carlo Bugatti (1902) (Musée D'Orsay) Circular chair by Carlo Bugatti (1902) (Furniture Museum of Milan)

Circular chair by Carlo Bugatti (1902) (Furniture Museum of Milan) Coffee serving table (1907) (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Coffee serving table (1907) (Cleveland Museum of Art) Dancing elephant radiator cap by Rembrandt Bugatti (1908-1928)

Dancing elephant radiator cap by Rembrandt Bugatti (1908-1928) Table by Eugenio Quarti (1900)

Table by Eugenio Quarti (1900) Museum or tea table by Eugenio Quarti (Wolfsonian-FIU Museum)

Museum or tea table by Eugenio Quarti (Wolfsonian-FIU Museum)

Architecture

The architecture of the Liberty style was more closely akin to the Baroque style. with a lavish excess of external ornament. Pietro Fenoglio was one of the early figures in Liberty style architecture, with the Casa Fenoglio-Lafleur in Turin, which added Art Nouveau elements onto a more traditional facade.[8] In Palermo the major figure was Ernesto Basile, who used curved forms similar to the Belgian-French Art Nouveau combined with symbolist murals, as in the Grand Hotel Villa Igiea (1899–1900). Basile also combined elements of a medieval castle with Liberty decoration to create the Villino Florio in Palermo (1899–1902).[9]

Milan had a large number of Liberty style houses. The most prominent architects included Giovanni Battista Bossi, whose Casa Galimberti had a facade drenched with decorative sculpture and murals. The decoration seemed to have been poured over the building. The sculpture somewhat recalls the work of the Renaissance painter Giuseppe Archimboldo.

Villino Florio in Palermo by Ernesto Basile (1899–1902)

Villino Florio in Palermo by Ernesto Basile (1899–1902) Casa Fenoglio-Lafleur by Pietro Fenoglio (about 1902)

Casa Fenoglio-Lafleur by Pietro Fenoglio (about 1902).jpg.webp) Villa Scott by Pietro Fenoglio

Villa Scott by Pietro Fenoglio Palazzo Castiglioni in Milan by Giuseppe Sommaruga (1901–1903)

Palazzo Castiglioni in Milan by Giuseppe Sommaruga (1901–1903).jpg.webp) Casa Galimberti in Milan by Giovanni Battista Bossi (1903–1905)

Casa Galimberti in Milan by Giovanni Battista Bossi (1903–1905) Casa Guazzoni in Milan by Giovanni Battista Bossi (1904–1906)

Casa Guazzoni in Milan by Giovanni Battista Bossi (1904–1906).JPG.webp) Kiosk in Palermo by Ernesto Basile

Kiosk in Palermo by Ernesto Basile

Frescoes

A distinctive element of Liberty style was the use of frescoes for the interior and exterior decoration. One example is found in Livorno in the decoration of the thermal baths at Acque della Salute. The frescos were painted by Ernesto Bellandi (1842-1916).

Painted interiors were a speciality of Ernesto Basile of Palermo, an architect devoted special attention to the fusion of the architecture decoration in the interiors. He created a series of villas around Palermo between 1899 and 1901.[2][9]

Interior decoration in the Liberty style continued longer in Italy than in other parts of Europe. An example is the decoration of interiors by Galileo Chini on the themes of autumn and spring, painted in 1922 for the Terme Berzieri in Salsomaggiore.[10]

Salon of the Grand Hotel Villa Igiea in Palermo by Ernesto Basile (1899-1900), with symbolist murals

Salon of the Grand Hotel Villa Igiea in Palermo by Ernesto Basile (1899-1900), with symbolist murals Frescos at the Thermal Baths in Livorno by Ernesto Bellandi

Frescos at the Thermal Baths in Livorno by Ernesto Bellandi Autumn and Spring frescoes by Galileo Chini in Salsomaggiore (1922)

Autumn and Spring frescoes by Galileo Chini in Salsomaggiore (1922)

Glass and ceramics

Glass and ceramics were important components of the Liberty style. Italian glass art particularly drew upon the tradition of Murano glass, from Venice. Galileo Chini was the dominant figure in glassware and ceramics. He created decorative floral designs which were produced in stained glass, majolica or ceramics. In 1897 he founded the Florentine Society of Ceramic Arts, and between 1902 and 1914 he decorated the salons of the Venice Biennale. He also became the chair of the department of decoration in the Italian Academy of Fine Arts. He was called to Bangkok in 1911–13 to decorate the throne room of the royal palace there.[10] Later works by Chini, with more geometric rather than natural designs, showed the growing influence of the more geometric style of the Vienna Secession and the work of Gustav Klimt.[10]

Vase by Fratelli Toso (about 1910) with more geometric floral style

Vase by Fratelli Toso (about 1910) with more geometric floral style Ceramic tile decoration by Galileo Chini, with influence of Vienna Secession

Ceramic tile decoration by Galileo Chini, with influence of Vienna Secession Polychrome majolica ceramic vase from the workshop of Galileo Chini (1906-1911)

Polychrome majolica ceramic vase from the workshop of Galileo Chini (1906-1911)

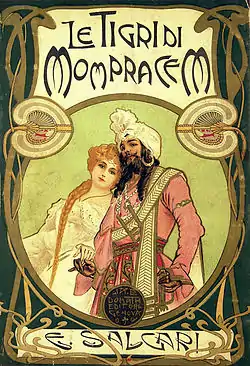

Graphic arts

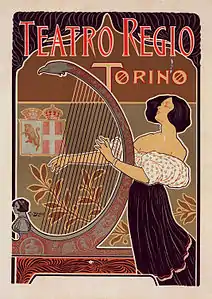

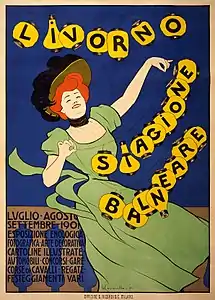

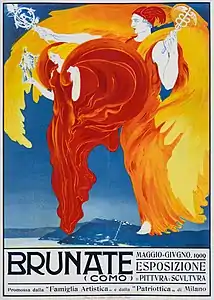

As in France and other parts of Europe, the poster and other graphic arts was an important genre of the Liberty style, particularly for travel posters. Leonetto Cappiello was an important figure in the early style, though he moved to Paris and spent most of his career designing posters and graphics there. Leonardo Bistolfi designed the poster for the 1902 Exposition in Turin, with the combination of feminine and floral themes typical of the early style.[11]

In its later years, the Liberty Style in graphics and painting moved away from floral and feminine themes to more modernist subjects, under the influence of Futurism. The painter and graphic artist Umberto Boccioni became one of the major figures in Futurism.

Poster for gas lamps by Giovanni Mataloni (1896)

Poster for gas lamps by Giovanni Mataloni (1896) Poster for Teatro Regio by Giuseppe Boano (1898)

Poster for Teatro Regio by Giuseppe Boano (1898) Book cover designed by Alberto Della Valle (1900)

Book cover designed by Alberto Della Valle (1900) Poster for baths of Livorno by Leonetto Cappiello (1901)

Poster for baths of Livorno by Leonetto Cappiello (1901) Poster for the Giornale di Sicilia by Mario Borgoni (1903)

Poster for the Giornale di Sicilia by Mario Borgoni (1903) Poster by Umberto Boccioni (1909)

Poster by Umberto Boccioni (1909)

Notes and citations

- Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 179.

- Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 187.

- Cited in Fahr-Becker, L'Art Nouveau (2015), p. 187

- Team, Web Marketing. "About Italian Design: Arts and Crafts". www.aboutitaliandesign.info. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- Riley 2004, pp. 310–311.

- Fahr-Becker 2015, pp. 180–81.

- Tasso, Francesca. "Salotto Quarti Eugenio". Lombardia Beni Culturali. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Sanna & Farina 2011, p. 67.

- Sanna & Farina 2011, p. 74.

- Sanna & Farina 2011, p. 588.

- Sanna & Farina 2011, p. 228.

Bibliography

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2015). L'Art Nouveau (in French). H.F. Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0857-5.

- Sanna, Angela; Farina, Violetta (2011). Art Nouveau (in French). Paris: Editions Place des Victoires. ISBN 978-2-8099-0418-5.

- Riley, Noêl (2004). Grammaire des Arts Decoratifs (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0801-1327-6.

- Malandrino, Gaetano (2010). Il Liberty in Europa tra secessioni e modernità (in Italian). USA,©: Lulu edition. ISBN 9781445273242.