Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death.[1][2] It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthaginians, and Romans,[1] among others. Crucifixion has been used in some countries as recently as the early 20th century.[3]

The crucifixion of Jesus is central to Christianity,[1] and the cross (sometimes depicting Jesus nailed to it) is the main religious symbol for many Christian churches.

Terminology

Ancient Greek has two verbs for crucify: anastauroo (ἀνασταυρόω), from stauros (which in modern Greek only means "cross" but which in antiquity was used of any kind of wooden pole, pointed or blunt, bare or with attachments) and apotumpanizo (ἀποτυμπανίζω) "crucify on a plank",[4] together with anaskolopizo (ἀνασκολοπίζω "impale"). In earlier pre-Roman Greek texts anastauro usually means "impale".[5][6][7]

The Greek used in the Christian New Testament uses four verbs, three of them based upon stauros (σταυρός), usually translated "cross". The most common term is stauroo (σταυρόω), "to crucify", occurring 46 times; sustauroo (συσταυρόω), "to crucify with" or "alongside" occurs five times, while anastauroo (ἀνασταυρόω), "to crucify again" occurs only once at the Epistle to the Hebrews 6:6. Prospegnumi (προσπήγνυμι), "to fix or fasten to, impale, crucify" occurs only once, at the Acts of the Apostles 2:23.

The English term cross derives from the Latin word crux,[8] which classically referred to a tree or any construction of wood used to hang criminals as a form of execution. The term later came to refer specifically to a cross.[9] The related term crucifix derives from the Latin crucifixus or cruci fixus, past participle passive of crucifigere or cruci figere, meaning "to crucify" or "to fasten to a cross".[10][11][12][13]

Detail

Cross shape

In the Roman Empire, the gibbet (instrument of execution) for crucifixions took on many shapes. Seneca the Younger (c. 4 BCE–65 CE) states: "I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet."[14] According to Josephus, during Emperor Titus's Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE), Roman soldiers nailed innumerable Jewish captives to crosses in various ways.[2]

At times the gibbet was only one vertical stake, called in Latin crux simplex.[15] This was the simplest available construction for torturing and killing the condemned. Frequently, however, there was a cross-piece attached either at the top to give the shape of a T (crux commissa) or just below the top, as in the form most familiar in Christian symbolism (crux immissa).[16] The most ancient image of a Roman crucifixion depicts an individual on a T-shaped cross. It is a graffito found in a taberna (hostel for wayfarers) in Puteoli, dating to the time of Trajan or Hadrian (late 1st century to early 2nd century CE).[17]

Second-century writers who speak of the execution cross describe the crucified person's arms as outstretched, not attached to a single stake: Lucian speaks of Prometheus as crucified "above the ravine with his hands outstretched". He also says that the shape of the letter T (the Greek letter tau) was that of the wooden instrument used for crucifying.[18] Artemidorus, another writer of the same period, says that a cross is made of posts (plural) and nails and that the arms of the crucified are outstretched.[19] Speaking of the generic execution cross, Irenaeus (c. 130–202), a Christian writer, describes it as composed of an upright and a transverse beam, sometimes with a small projection in the upright.[20]

New Testament writings about the crucifixion of Jesus do not specify the shape of that cross, but subsequent early writings liken it to the letter T. According to William Barclay, because the Greek letter T is shaped exactly like the crux commissa and represented the number 300, "wherever the fathers came across the number 300 in the Old Testament they took it to be a mystical prefiguring of the cross of Christ".[21] The earliest example, written around the late first century CE, is the Epistle of Barnabas,[22] with another example being Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215).[23]

Justin Martyr (c. 100 – c. 165) sees the cross of Christ represented in the crossed spits used to roast the Passover lamb.[24]

Nail placement

In popular depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus (possibly because in translations of John 20:25 the wounds are described as being "in his hands"), Jesus is shown with nails in his hands. But in Greek the word "χείρ", usually translated as "hand", could refer to the entire portion of the arm below the elbow,[25] and to denote the hand as distinct from the arm some other word could be added, as "ἄκρην οὔτασε χεῖρα" (he wounded the end of the χείρ, i.e., "he wounded him in the hand".[26]

A possibility that does not require tying is that the nails were inserted just above the wrist, through the soft tissue, between the two bones of the forearm (the radius and the ulna).[27]

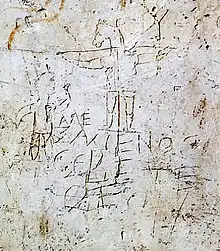

A foot-rest (suppedaneum) attached to the cross, perhaps for the purpose of taking the person's weight off the wrists, is sometimes included in representations of the crucifixion of Jesus but is not discussed in ancient sources. Some scholars interpret the Alexamenos graffito (c. 200), the earliest surviving depiction of the crucifixion, as including such a foot-rest.[28] Ancient sources also mention the sedile, a small seat attached to the front of the cross, about halfway down,[29] which could have served a similar purpose.

In 1968, archaeologists discovered at Giv'at ha-Mivtar in northeast Jerusalem the remains of one Jehohanan, who was crucified in the 1st century CE. The remains included a heel bone with a nail driven through it from the side. The tip of the nail was bent, perhaps because of striking a knot in the upright beam, which prevented it being extracted from the foot. A first inaccurate account of the length of the nail led some to believe that it had been driven through both heels, suggesting that the man had been placed in a sort of sidesaddle position, but the true length of the nail, 11.5 centimetres (4+1⁄2 inches), suggests instead that in this case of crucifixion the heels were nailed to opposite sides of the upright.[30][31][32] As of 2011, the skeleton from Giv'at ha-Mivtar was the only confirmed example of ancient crucifixion in the archaeological record.[33] A second set of skeletal remains with holes transverse through the calcaneum heel bones, found in 2007, could be a second archaeological record of crucifixion.[34] The find in Cambridgeshire (United Kingdom) in November 2017 of the remains of the heel bone of a (probably enslaved) man with an iron nail through it, is believed by the archeologists to confirm the use of this method in ancient Rome.[35]

Cause of death

The length of time required to reach death could range from hours to days depending on method, the victim's health, and the environment.[36][37]

A theory attributed to Pierre Barbet held that, when the whole body weight was supported by the stretched arms, the typical cause of death was asphyxiation.[38] He wrote that the condemned would have severe difficulty inhaling, due to hyper-expansion of the chest muscles and lungs. The condemned would therefore have to draw himself up by the arms, leading to exhaustion, or have his feet supported by tying or by a wood block. When no longer able to lift himself, the condemned would die within a few minutes. This theory has been supported by multiple scholars.[39] Other scholars, including Frederick Zugibe, posit other causes of death. Zugibe suspended test subjects with their arms at 60° to 70° from the vertical. The test subjects had no difficulty breathing during experiments, but did suffer rapidly increasing pain,[40][41] which is consistent with the Roman use of crucifixion to achieve a prolonged, agonizing death. However, Zugibe's positioning of the test subjects necessarily did not precisely replicate the conditions of historical crucifixion.[42] In 2023, an analysis of medical literature concluded that asphyxiation is discredited as the primary cause of death from crucifixion.[43]

There is scholarly support for several[42] possible non-asphyxiation causes of death: heart failure or arrhythmia,[44][45] hypovolemic shock,[41] acidosis,[46] dehydration,[36] and pulmonary embolism.[47] Death could result from any combination of those factors, or from other causes, including sepsis following infection due to the wounds caused by the nails or by the scourging that often preceded crucifixion, or from stabbing by the guards.[36][39][44]

Survival

Since death does not follow immediately on crucifixion, survival after a short period of crucifixion is possible, as in the case of those who choose each year as a devotional practice to be non-lethally crucified.

There is an ancient record of one person who survived a crucifixion that was intended to be lethal, but was interrupted. Josephus recounts:

I saw many captives crucified, and remembered three of them as my former acquaintances. I was very sorry at this in my mind, and went with tears in my eyes to Titus, and told him of them; so he immediately commanded them to be taken down, and to have the greatest care taken of them, in order to their recovery; yet two of them died under the physician's hands, while the third recovered.[48]

Josephus gives no details of the method or duration of the crucifixion of his three friends before their reprieve.

History and religious texts

Pre-Roman states

Crucifixion (or impalement), in one form or another, was used by Persians, Carthaginians, and among the Greeks, the Macedonians.

The Greeks were generally opposed to performing crucifixions.[49] However, in his Histories, ix.120–122, Greek writer Herodotus describes the execution of a Persian general at the hands of Athenians in about 479 BC: "They nailed him to a plank and hung him up ... this Artayctes who suffered death by crucifixion."[50] The Commentary on Herodotus by How and Wells remarks: "They crucified him with hands and feet stretched out and nailed to cross-pieces; cf. vii.33. This barbarity, unusual on the part of Greeks, may be explained by the enormity of the outrage or by Athenian deference to local feeling."[51]

Some Christian theologians, beginning with Paul of Tarsus writing in Galatians 3:13, have interpreted an allusion to crucifixion in Deuteronomy 21:22–23. This reference is to being hanged from a tree, and may be associated with lynching or traditional hanging. However, Rabbinic law limited capital punishment to just 4 methods of execution: stoning, burning, strangulation, and decapitation, while the passage in Deuteronomy was interpreted as an obligation to hang the corpse on a tree as a form of deterrence.[52] The fragmentary Aramaic Testament of Levi (DSS 4Q541) interprets in column 6: "God ... (partially legible)-will set ... right errors. ... (partially legible)-He will judge ... revealed sins. Investigate and seek and know how Jonah wept. Thus, you shall not destroy the weak by wasting away or by ... (partially legible)-crucifixion ... Let not the nail touch him."[53]

The Jewish king Alexander Jannaeus, king of Judea from 103 to 76 BCE, crucified 800 rebels, said to be Pharisees, in the middle of Jerusalem.[54][55]

Alexander the Great is reputed to have crucified 2,000 survivors from his siege of the Phoenician city of Tyre,[56] as well as the doctor who unsuccessfully treated Alexander's lifelong friend Hephaestion. Some historians have also conjectured that Alexander crucified Callisthenes, his official historian and biographer, for objecting to Alexander's adoption of the Persian ceremony of royal adoration.

In Carthage, crucifixion was an established mode of execution, which could even be imposed on generals for suffering a major defeat.[57][58][59]

The oldest crucifixion may be a post-mortem one mentioned by Herodotus. Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, was put to death in 522 BCE by Persians, and his dead body was then crucified.[60]

History

The Greek and Latin words corresponding to "crucifixion" applied to many different forms of painful execution, including being impaled on a stake, or affixed to a tree, upright pole (a crux simplex), or to a combination of an upright (in Latin, stipes) and a crossbeam (in Latin, patibulum). Seneca the Younger wrote: "I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet".[61]

Crucifixion was generally performed within Ancient Rome as a means to dissuade others from perpetrating similar crimes, with victims sometimes left on display after death as a warning. Crucifixion was intended to provide a death that was particularly slow, painful (hence the term excruciating, literally "out of crucifying"), gruesome, humiliating, and public, using whatever means were most expedient for that goal. Crucifixion methods varied considerably with location and period.

One hypothesis suggested that the Ancient Roman custom of crucifixion may have developed out of a primitive custom of arbori suspendere—hanging on an arbor infelix ("inauspicious tree") dedicated to the gods of the nether world. This hypothesis is rejected by William A. Oldfather, who shows that this form of execution (the supplicium more maiorum, punishment in accordance with the custom of our ancestors) consisted of suspending someone from a tree, not dedicated to any particular gods, and flogging him to death.[62] Tertullian mentions a 1st-century AD case in which trees were used for crucifixion,[63] but Seneca the Younger earlier used the phrase infelix lignum (unfortunate wood) for the transom ("patibulum") or the whole cross.[64] Plautus and Plutarch are the two main sources for accounts of criminals carrying their own patibula to the upright stipes.[65]

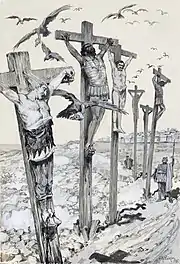

Notorious mass crucifixions followed the Third Servile War in 73–71 BCE (the slave rebellion under Spartacus), and other Roman civil wars in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE. Crassus ordered the crucifixion of 6,000 of Spartacus' followers who had been hunted down and captured after the slave defeat in battle.[66] Josephus says that in the siege that led to the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70, the Roman soldiers crucified Jewish captives before the walls of Jerusalem and out of anger and hatred amused themselves by nailing them in different positions.[67]

In some cases, the condemned was forced to carry the crossbeam to the place of execution.[68] A whole cross would weigh well over 135 kg (300 lb), but the crossbeam would not be as burdensome, weighing around 45 kg (100 lb).[69] The Roman historian Tacitus records that the city of Rome had a specific place for carrying out executions, situated outside the Esquiline Gate,[70] and had a specific area reserved for the execution of slaves by crucifixion.[71] Upright posts would presumably be fixed permanently in that place, and the crossbeam, with the condemned person perhaps already nailed to it, would then be attached to the post.

The person executed may have been attached to the cross by rope, though nails and other sharp materials are mentioned in a passage by Josephus, where he states that at the Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE), "the soldiers out of rage and hatred, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest".[72] Objects used in the crucifixion of criminals, such as nails, were sought as amulets with perceived medicinal qualities.[73]

While a crucifixion was an execution, it was also a humiliation, by making the condemned as vulnerable as possible. Although artists have traditionally depicted the figure on a cross with a loin cloth or a covering of the genitals, the person being crucified was usually stripped naked. Writings by Seneca the Younger state some victims suffered a stick forced upwards through their groin.[14][74] Despite its frequent use by the Romans, the horrors of crucifixion did not escape criticism by some eminent Roman orators. Cicero, for example, described crucifixion as "a most cruel and disgusting punishment",[75] and suggested that "the very mention of the cross should be far removed not only from a Roman citizen's body, but from his mind, his eyes, his ears".[76] Elsewhere he says, "It is a crime to bind a Roman citizen; to scourge him is a wickedness; to put him to death is almost parricide. What shall I say of crucifying him? So guilty an action cannot by any possibility be adequately expressed by any name bad enough for it."[77]

Frequently, the legs of the person executed were broken or shattered with an iron club, an act called crurifragium, which was also frequently applied without crucifixion to slaves.[78] This act hastened the death of the person but was also meant to deter those who observed the crucifixion from committing offenses.[78]

Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, abolished crucifixion in the Roman Empire in 337 out of veneration for Jesus Christ, its most famous victim.[79][80][81]

Society and law

Crucifixion was intended to be a gruesome spectacle: the most painful and humiliating death imaginable.[82][83] It was used to punish slaves, pirates, and enemies of the state. It was originally reserved for slaves (hence still called "supplicium servile" by Seneca), and later extended to citizens of the lower classes (humiliores).[29] The victims of crucifixion were stripped naked[29][84] and put on public display[85][86] while they were slowly tortured to death so that they would serve as a spectacle and an example.[82][83]

According to Roman law, if a slave killed his or her enslaver, all of the enslaver's slaves would be crucified as punishment.[87] Both men and women were crucified.[88][89][86] Tacitus writes in his Annals that when Lucius Pedanius Secundus was murdered by a slave, some in the Senate tried to prevent the mass crucifixion of four hundred of his slaves[87] because there were so many women and children, but in the end tradition prevailed and they were all executed.[90] Although not conclusive evidence for female crucifixion by itself, the most ancient image of a Roman crucifixion may depict a crucified woman, whether real or imaginary.[lower-alpha 1] Crucifixion was such a gruesome and humiliating way to die that the subject was somewhat of a taboo in Roman culture, and few crucifixions were specifically documented. One of the only specific female crucifixions that are documented is that of Ida, a freedwoman (former slave) who was crucified by order of Tiberius.[91][92]

Process

Crucifixion was typically carried out by specialized teams, consisting of a commanding centurion and his soldiers.[93] First, the condemned would be stripped naked[93] and scourged.[29] This would cause the person to lose a large amount of blood, and approach a state of shock. The convict then usually had to carry the horizontal beam (patibulum in Latin) to the place of execution, but not necessarily the whole cross.[29]

During the death march, the prisoner, probably[94] still nude after the scourging,[93] would be led through the most crowded streets[85] bearing a titulus – a sign board proclaiming the prisoner's name and crime.[29][86][93] Upon arrival at the place of execution, selected to be especially public,[86][85][95] the convict would be stripped of any remaining clothing, then nailed to the cross naked.[68][29][86][95] If the crucifixion took place in an established place of execution, the vertical beam (stipes) might be permanently embedded in the ground.[29][93] In this case, the condemned person's wrists would first be nailed to the patibulum, and then he or she would be hoisted off the ground with ropes to hang from the elevated patibulum while it was fastened to the stipes.[29][93] Next the feet or ankles would be nailed to the upright stake.[29][93] The 'nails' were tapered iron spikes approximately 13 to 18 cm (5 to 7 in) long, with a square shaft 10 millimetres (3⁄8 in) across.[30] The titulus would also be fastened to the cross to notify onlookers of the person's name and crime as they hung on the cross, further maximizing the public impact.[86][93]

There may have been considerable variation in the position in which prisoners were nailed to their crosses and how their bodies were supported while they died.[83] Seneca the Younger recounts: "I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet."[14] One source claims that for Jews (apparently not for others), a man would be crucified with his back to the cross as is traditionally depicted, while a woman would be nailed facing her cross, probably with her back to onlookers, or at least with the stipes providing some semblance of modesty if viewed from the front.[32] Such concessions were "unique" and not made outside a Jewish context.[32] Several sources mention some sort of seat fastened to the stipes to help support the person's body,[96][97][98] thereby prolonging the person's suffering[85] and humiliation[83] by preventing the asphyxiation caused by hanging without support. Justin Martyr calls the seat a cornu, or "horn,"[96] leading some scholars to believe it may have had a pointed shape designed to torment the crucified person.[99] This would be consistent with Seneca's observation of victims with their private parts impaled.

In Roman-style crucifixion, the condemned could take up to a few days to die, but death was sometimes hastened by human action. "The attending Roman guards could leave the site only after the victim had died, and were known to precipitate death by means of deliberate fracturing of the tibia and/or fibula, spear stab wounds into the heart, sharp blows to the front of the chest, or a smoking fire built at the foot of the cross to asphyxiate the victim."[36] The Romans sometimes broke the prisoner's legs to hasten death and usually forbade burial.[86] On the other hand, the person was often deliberately kept alive as long as possible to prolong their suffering and humiliation, so as to provide the maximum deterrent effect.[83] Corpses of the crucified were typically left on the crosses to decompose and be eaten by animals.[83][100]

In Islam

Islam spread in a region where many societies, including the Persian and Roman empires, had used crucifixion to punish traitors, rebels, robbers and criminal slaves.[101] The Qur'an refers to crucifixion in six passages, of which the most significant for later legal developments is verse 5:33:[102][101]

The punishment of those who wage war against Allah and His Apostle, and strive with might and main for mischief through the land is: execution, or crucifixion, or the cutting off of hands and feet from opposite sides, or exile from the land: that is their disgrace in this world, and a heavy punishment is theirs in the Hereafter.[103]

The corpus of hadith provides contradictory statements about the first use of crucifixion under Islamic rule, attributing it variously to Muhammad himself (for murder and robbery of a shepherd) or to the second caliph Umar (applied to two slaves who murdered their mistress).[101] Classical Islamic jurisprudence applies the verse 5:33 chiefly to highway robbers, as a hadd (scripturally prescribed) punishment.[101] The preference for crucifixion over the other punishments mentioned in the verse or for their combination (which Sadakat Kadri has called "Islam's equivalent of the hanging, drawing and quartering that medieval Europeans inflicted on traitors")[104] is subject to "complex and contested rules" in classical jurisprudence.[101] Most scholars required crucifixion for highway robbery combined with murder, while others allowed execution by other methods for this scenario.[101] The main methods of crucifixion are:[101]

- Exposure of the culprit's body after execution by another method, ascribed to "most scholars"[101][105] and in particular to Ibn Hanbal and Al-Shafi'i;[106] or Hanbalis and Shafi'is.[107]

- Crucifying the culprit alive, then executing him with a lance thrust or another method, ascribed to Malikis, most Hanafis and most Twelver Shi'is;[101] the majority of the Malikis;[105] Malik, Abu Hanifa, and al-Awza'i;[106] or Malikis, Hanafis, and Shafi'is.[107]

- Crucifying the culprit alive and sparing his life if he survives for three days, ascribed to Shiites.[105]

Most classical jurists limit the period of crucifixion to three days.[101] Crucifixion involves affixing or impaling the body to a beam or a tree trunk.[101] Various minority opinions also prescribed crucifixion as punishment for a number of other crimes.[101] Cases of crucifixion under most of the legally prescribed categories have been recorded in the history of Islam, and prolonged exposure of crucified bodies was especially common for political and religious opponents.[101][108]

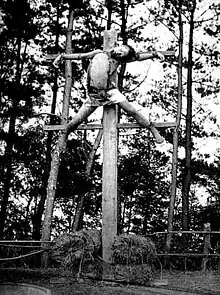

Japan

Crucifixion was introduced into Japan during the Sengoku period (1467–1573), after a 350-year period with no capital punishment.[111] It is believed to have been suggested to the Japanese by the introduction of Christianity into the region,[111] although similar types of punishment had been used as early as the Kamakura period. Known in Japanese as haritsuke (磔), crucifixion was used in Japan before and during the Tokugawa Shogunate. Several related crucifixion techniques were used. Petra Schmidt, in "Capital Punishment in Japan", writes:[112]

Execution by crucifixion included, first of all, hikimawashi (i.e, being paraded about town on horseback); then the unfortunate was tied to a cross made from one vertical and two horizontal poles. The cross was raised, the convict speared several times from two sides, and eventually killed with a final thrust through the throat. The corpse was left on the cross for three days. If one condemned to crucifixion died in prison, his body was pickled and the punishment executed on the dead body. Under Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the great 16th-century unifiers, crucifixion upside down (i.e, sakasaharitsuke) was frequently used. Water crucifixion (mizuharitsuke) awaited mostly Christians: a cross was raised at low tide; when the high tide came, the convict was submerged under water up to the head, prolonging death for many days

In 1597, 26 Christian Martyrs were nailed to crosses at Nagasaki, Japan. Among those executed were Saints Paulo Miki, Philip of Jesus and Pedro Bautista, a Spanish Franciscan. The executions marked the beginning of a long history of persecution of Christianity in Japan, which continued until its decriminalization in 1871.

Crucifixion was used as a punishment for prisoners of war during World War II. Ringer Edwards, an Australian prisoner of war, was crucified for killing cattle, along with two others. He survived 63 hours before being let down.

Burma

In Burma, crucifixion was a central element in several execution rituals. Felix Carey, a missionary in Burma from 1806 to 1812,[113] wrote the following:[114]

Four or five persons, after being nailed through their hands and feet to a scaffold, had first their tongues cut out, then their mouths slit open from ear to ear, then their ears cut off, and finally their bellies ripped open.

Six people were crucified in the following manner: their hands and feet nailed to a scaffold; then their eyes were extracted with a blunt hook; and in this condition they were left to expire; two died in the course of four days; the rest were liberated, but died of mortification on the sixth or seventh day.

Four persons were crucified, viz. not nailed but tied with their hands and feet stretched out at full length, in an erect posture. In this posture they were to remain till death; every thing they wished to eat was ordered them with a view to prolong their lives and misery. In cases like this, the legs and feet of the criminals begin to swell and mortify at the expiration of three or four days; some are said to live in this state for a fortnight, and expire at last from fatigue and mortification. Those which I saw, were liberated at the end of three or four days.

Europe

During World War I, there were persistent rumors that German soldiers had crucified a Canadian soldier on a tree or barn door with bayonets or combat knives. The event was initially reported in 1915 by Private George Barrie of the 1st Canadian Division. Two investigations, one a post-war official investigation, and the other an independent investigation by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, concluded that there was no evidence to support the story.[115] However, British documentary maker Iain Overton in 2001 published an article claiming that the story was true, identifying the soldier as Harry Band.[115][116] Overton's article was the basis for a 2002 episode of the Channel 4 documentary show Secret History.[117]

It has been reported that crucifixion was used in several cases against the German civil population of East Prussia when it was occupied by Soviet forces at the end of World War II.[118]

Archaeological evidence

Although the Roman historians Josephus and Appian refer to the crucifixion of thousands of Jews by the Romans, there are few actual archaeological remains. An exception is the crucified body of a Jew dating back to the first century CE which was discovered at Givat HaMivtar, Jerusalem in 1968.[119] The remains were found accidentally in an ossuary with the crucified man's name on it, "Jehohanan, the son of Hagakol."[120][121] Nicu Haas, from the Hebrew University Medical School, examined the ossuary and discovered that it contained a heel bone with a nail driven through its side, indicating that the man had been crucified. The position of the nail relative to the bone suggests the feet had been nailed to the cross from their side, not from their front; various opinions have been proposed as to whether they were both nailed together to the front of the cross or one on the left side, one on the right side. The point of the nail had olive wood fragments on it indicating that he was crucified on a cross made of olive wood or on an olive tree.

Additionally, a piece of acacia wood was located between the bones and the head of the nail, presumably to keep the condemned from freeing his foot by sliding it over the nail. His legs were found broken, possibly to hasten his death. It is thought that because in earlier Roman times iron was valuable, the nails were removed from the dead body to conserve costs. According to Haas, this could help to explain why only one nail has been found, as the tip of the nail in question was bent in such a way that it could not be removed. Haas had also identified a scratch on the inner surface of the right radius bone of the forearm, close to the wrist. He deduced from the form of the scratch, as well as from the intact wrist bones, that a nail had been driven into the forearm at that position.

Many of Haas' findings have, however, been challenged. For instance, it was subsequently determined that the scratches in the wrist area were non-traumatic – and, therefore, not evidence of crucifixion – while reexamination of the heel bone revealed that the two heels were not nailed together, but rather separately to either side of the upright post of the cross.[122]

In 2007, a possible case of a crucified body, with a round hole in a heel bone, possibly caused by a nail, was discovered in the Po Valley near Rovigo, in northern Italy.[123] In 2017 part of a crucified body, with a nail in the heel, was additionally discovered at Fenstanton in the United Kingdom.[124] Further studies suggested that the remains may be those of a slave, because at that time crucifixion was banned in Roman law for citizens, although not necessarily for slaves.[125]

Modern use

Legal execution in Islamic states

Crucifixion is still used as a rare method of execution in Saudi Arabia. The punishment of crucifixion (șalb) imposed in Islamic law is variously interpreted as exposure of the body after execution, crucifixion followed by stabbing in the chest, or crucifixion for three days, survivors of which are allowed to live.[126]

Several people have been subjected to crucifixion in Saudi Arabia in the 2000s, although on occasion they were first beheaded and then crucified. In March 2013, a robber was set to be executed by being crucified for three days.[127] However, the method was changed to death by firing squad.[128] The Saudi Press Agency reported that the body of another individual was crucified after his execution in April 2019 as part of a crackdown on charges of terrorism.[129][130]

Ali Mohammed Baqir al-Nimr was arrested in 2012 when he was 17 years old for taking part in an anti-government protest in Saudi Arabia during the Arab Spring.[131] In May 2014, Ali al-Nimr was sentenced to be publicly beheaded and crucified.[132]

Theoretically, crucifixion is still one of the Hadd punishments in Iran.[133][134] If a crucified person were to survive three days of crucifixion, that person would be allowed to live.[135] Execution by hanging is described as follows: "In execution by hanging, the prisoner will be hung on a hanging truss which should look like a cross, while his (her) back is toward the cross, and (s)he faces the direction of Mecca [in Saudi Arabia], and his (her) legs are vertical and distant from the ground."[136]

Sudan's penal code, based upon the government's interpretation of shari'a,[137][138][139] includes execution followed by crucifixion as a penalty. When, in 2002, 88 people were sentenced to death for crimes relating to murder, armed robbery, and participating in ethnic clashes, Amnesty International wrote that they could be executed by either hanging or crucifixion.[140]

Jihadism

On 5 February 2015, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) reported that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) had committed "several cases of mass executions of boys, as well as reports of beheadings, crucifixions of children and burying children alive".[141]

On 30 April 2014, a total of seven public executions were carried out in Raqqa, northern Syria.[142] The pictures, originally posted to Twitter by a student at Oxford University, were retweeted by a Twitter account owned by a known member of ISIL causing major media outlets to incorrectly attribute the origin of the post to the militant group.[143] In most of these cases of crucifixion the victims are shot first then their bodies are displayed[144] but there have also been reports of crucifixion preceding shootings or decapitations[145] as well as a case where a man was said to have been "crucified alive for eight hours" with no indication of whether he died.[144]

Other incidents

The human rights group Karen Women Organization documented a case of Tatmadaw forces crucifying several Karen villagers in 2000 in the Dooplaya District in Burma's Kayin State.[146][147]

On 22 January 2014, Dmytro Bulatov, a Ukrainian anti-government activist and member of AutoMaidan, claimed to have been kidnapped by unknown persons "speaking in Russian accents" and tortured for a week. His captors kept him in the dark, beat him, cut off a piece of his ear, and nailed him to a cross. His captors ultimately left him in a forest outside Kyiv after forcing him to confess to being an American spy and accepting money from the US Embassy in Ukraine to organize protests against then-President Viktor Yanukovych.[148][149][150] Bulatov said he believed Russian secret services were responsible.[151]

In 1997, the Ministry of Justice in the United Arab Emirates issued a statement that a court had sentenced two murderers to be crucified, to be followed by their executions the next day.[152][153] A Ministry of Justice official later stated that the crucifixion sentence should be considered cancelled.[154] The crucifixions were not carried out, and the convicts were instead executed by firing squad.[155]

In culture and arts

Sculpture construction: Crucifixion, homage to Mondrian, by Barbara Hepworth, United Kingdom (2007)

Sculpture construction: Crucifixion, homage to Mondrian, by Barbara Hepworth, United Kingdom (2007) Allegory of Poland (1914–1918), postcard by Sergey Solomko

Allegory of Poland (1914–1918), postcard by Sergey Solomko Car-float at the feast of the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos, Colonia Doctores, Mexico City (2011)

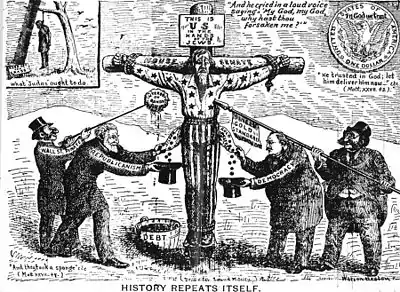

Car-float at the feast of the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos, Colonia Doctores, Mexico City (2011) Antisemitic American political cartoon, Sound Money magazine, April 15, 1896, issue

Antisemitic American political cartoon, Sound Money magazine, April 15, 1896, issue Protester tied to a cross in Washington D.C. (1970)

Protester tied to a cross in Washington D.C. (1970)

Christ Crucified, by Diego Velázquez (1632)

Christ Crucified, by Diego Velázquez (1632)

As a devotional practice

In July 1805, a man named Mattio Lovat attempted to crucify himself at a public street in Venice, Italy. The attempt was unsuccessful, and he was sent to an asylum, where he died a year later.[156]

In some cases, a crucifixion is simulated within a passion play, as in the ceremonial re-enactment that has been performed yearly in the town of Iztapalapa, on the outskirts of Mexico City, since 1833,[157] and in the famous Oberammergau Passion Play. Also, since at least the mid-19th century, a group of flagellants in New Mexico, called Hermanos de Luz ("Brothers of Light"), have annually conducted reenactments of Christ's crucifixion during Holy Week, in which a penitent is tied—but not nailed—to a cross.[158]

The Catholic Church frowns upon self-crucifixion as a form of devotion: "Penitential practices leading to self-crucifixion with nails are not to be encouraged."[159] Despite this, the practice persists in the Philippines, where some Catholics are voluntarily, non-lethally crucified for a limited time on Good Friday to imitate the sufferings of Christ. Pre-sterilised nails are driven through the palm of the hand between the bones, while there is a footrest to which the feet are nailed. Rolando del Campo, a carpenter in Pampanga, vowed to be crucified every Good Friday for 15 years if God would carry his wife through a difficult childbirth,[160] while in San Pedro Cutud, Ruben Enaje has been crucified 33 times.[161] The Filipino Catholic Church has repeatedly voiced disapproval of crucifixions and self-flagellation, while the government has noted that it cannot deter devotees. The Department of Health recommends that participants in the rites should have tetanus shots and that the nails used should be sterilized.[162]

Notable crucifixions

- The rebel slaves of the Third Servile War: Between 73 and 71 BCE, a band of slaves, eventually numbering about 120,000, under the (at least partial) leadership of Spartacus were in open revolt against the Roman republic. The rebellion was eventually crushed and, while Spartacus himself most likely died in the final battle of the revolt, approximately 6,000 of his followers were crucified along the 200-km Appian Way between Capua and Rome[163] as a warning to any other would-be rebels.

- Jehohanan: Jewish man who was crucified around the same time as Jesus; it is widely accepted that his ankles were nailed to the side of the stipes of the cross.

- Jesus: his reputed death by crucifixion under Pontius Pilate (c. 30 or 33 CE), recounted in the four 1st-century canonical Gospels, is referred to repeatedly as something well known in the earlier letters of Saint Paul, for instance, five times in his First Letter to the Corinthians, written in 57 CE (1:13, 1:18, 1:23, 2:2, 2:8). Pilate, the Roman governor of Judaea province at the time, is explicitly linked with the condemnation of Jesus by the Gospels, and subsequently by Tacitus.[164] The civil charge was a claim to be King of the Jews.

- Saint Peter: Christian apostle, who according to tradition was crucified upside-down at his own request (hence the Cross of Saint Peter),[165] because he did not feel worthy enough to die the same way as Jesus.

- Saint Andrew: Christian apostle and Saint Peter's brother, who is traditionally said to have been crucified on an X-shaped cross (hence the Saint Andrew's Cross).

- Simeon of Jerusalem: second Bishop of Jerusalem, crucified in either 106 or 107 CE.[166]

- Mani: the founder of Manicheanism, he was depicted by followers as having died by crucifixion in 274 CE.[167]

- Eulalia of Barcelona was venerated as a saint. According to her hagiography, she was stripped naked, tortured, and ultimately crucified on an X-shaped cross.[168]

- Wilgefortis was venerated as a saint and represented as a crucified woman, however her legend comes from a misinterpretation of a full-clothed crucifix known as the Volto Santo of Lucca.

- The 26 Martyrs of Japan: Japanese martyrs who were crucified and impaled with spears.

Notes

- It is a graffito found in a taberna (hostel for wayfarers) in Puteoli, dating to the time of Trajan or Hadrian (late 1st century to early 2nd century AD). An inscription over the person's left shoulder reads "Ἀλκίμιλα" (Alkimila), a female name. It is not clear, however, whether the inscription was written by the same person who drew the picture, or added by another person later. It is also not known whether the grafitto is intended to depict an actual event, as distinguished from, perhaps, the writer's desire for someone to be crucified, or as a jest. As such, the grafitto does not itself provide conclusive evidence of female crucifixion.[17]

References

- Granger Cook, John (2018). "Cross/Crucifixion". In Hunter, David G.; van Geest, Paul J. J.; Lietaert Peerbolte, Bert Jan (eds.). Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity Online. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2589-7993_EECO_SIM_00000808. ISSN 2589-7993.

- Josephus. The Jewish War. 5.11.1., Perseus Project BJ5.11.1, .

- Roger Bourke, Prisoners of the Japanese: Literary imagination and the prisoner-of-war experience (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2006), Chapter 2 "A Town Like Alice and the prisoner of war as Christ-figure", pp. 30–65.

- LSJ apotumpanizo ἀποτυμπα^ν-ίζω (later ἀποτύμπα^ν-τυπ- UPZ119 (2nd century BC), POxy.1798.1.7), A. crucify on a plank, D.8.61,9.61: – Pass., Lys.13.56, D.19.137, Arist. Rh. 1383a5, Beros. ap. J.Ap.1.20. 2. generally, destroy, Plu.2.1049d.

- LSJ anastauro ἀνασταυρ-όω, = foreg., Hdt.3.125, 6.30, al.; identical with ἀνασκολοπίζω, 9.78: – Pass., Th. 1.110, Pl.Grg.473c. II. in Rom. times, affix to a cross, crucify, Plb. 1.11.5, al., Plu.Fab.6, al. 2. crucify afresh, Ep.Hebr.6.6.

- Plutarch Fabius Maximus 6.3 "Hannibal now perceived the mistake in his position, and its peril, and crucified the native guides who were responsible for it."

- Polybius 1.11.5 [5] Historiae. Polybius. Theodorus Büttner-Wobst after L. Dindorf. Leipzig. Teubner. 1893.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary, "cross"". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary: crux, ŭcis, f. (m., Enn. ap. Non. p. 195, 13; Gracch. ap. Fest. s. v. masculino, p. 150, 24, and 151, 12 Müll.) [perh. kindred with circus]. I. Lit. A. In gen., a tree, frame, or other wooden instruments of execution, on which criminals were impaled or hanged, Sen. Prov. 3, 10; Cic. Rab. Perd. 3, 10 sqq. – B. In partic., a cross, Ter. And. 3, 5, 15; Cic. Verr. 2, 1, 3, § 7; 2, 1, 4, § 9; id. Pis. 18, 42; id. Fin. 5, 30, 92; Quint. 4, 2, 17; Tac. A. 15, 44; Hor. S. 1, 3, 82; 2, 7, 47; id. Ep. 1, 16, 48 et saep.: "dignus fuit qui malo cruce periret, Gracch. ap. Fest. l. l.: pendula", the pole of a carriage, Stat. S. 4, 3, 28.

- "Collins English Dictionary, "crucify"". Collins. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "Compact Oxford English Dictionary, "crucify"". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "Webster New World College Dictionary, "crucify"". yourdictionary.com/. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary, "crucify"". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- Seneca, Dialogue "To Marcia on Consolation", in Moral Essays, 6.20.3, trans. John W. Basore, The Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1946) 2:69

- Barclay, William (1998). The Apostles' Creed. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-664-25826-9.

- "The ... oldest depiction of a crucifixion ... was uncovered by archaeologists more than a century ago on the Palatine Hill in Rome. It is a second-century graffiti scratched into a wall that was part of the imperial palace complex. It includes a caption – not by a Christian, but by someone taunting and deriding Christians and the crucifixions they underwent. It shows crude stick-figures of a boy reverencing his 'God', who has the head of a jackass and is upon a cross with arms spread wide and with hands nailed to the crossbeam. Here we have a Roman sketch of a Roman crucifixion, and it is in the traditional cross shape." Clayton F. Bower Jr. "Cross or Torture Stake?" Archived 2008-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Cook, John Granger (2012). "Crucifixion as Spectacle in Roman Campania". Novum Testamentum. 54 (1): 60, 92–98. doi:10.1163/156853611X589651. JSTOR 23253630.

- "It was his body that tyrants took for a model, his shape that they imitated, when they set up the erections on which men are crucified" (Lucian, Trial in the Court of Vowels, p. 30

- Cook, John Granger (10 December 2018). John Granger Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World (Mohr Siebeck 2018), p. 289; cf. pp. 7−8. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-156001-9.

- "The very form of the cross, too, has five extremities, two in length, two in breadth, and one in the middle, on which [last] the person rests who is fixed by the nails" ( Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses II, 4).

- Barclay, William (1998). The Apostles' Creed. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-664-25826-9.

- Epistle of Barnabas, chapter 9

- "Clement of Alexandria, The Stromata, book VI, chapter 11".

- "Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, XL, 3".

That lamb which was commanded to be wholly roasted was a symbol of the suffering of the cross which Christ would undergo. For the lamb, which is roasted, is roasted and dressed up in the form of the cross. For one spit is transfixed right through from the lower parts up to the head, and one across the back, to which are attached the legs of the lamb.

- In the Homeric Greek of the Iliad XX, 478–480, a spear-point is said to have pierced the χεῖρ "where the sinews of the elbow join" (ἵνα τε ξενέχουσι τένοντες / ἀγκῶνος, τῇ τόν γε φίλης διὰ χειρὸς ἔπειρεν / αἰχμῇ χακλκείῃ).

- χείρ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Wynne-Jones, Jonathan (16 March 2008). "Why the BBC thinks Christ did not die this way". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 19 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- Viladesau, Richard (2006). The beauty of the cross: the passion of Christ in theology and the arts, from the catacombs to the eve of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-518811-0. OCLC 58791208.

- Kohler, Kaufmann; Hirsch, Emil G. "Crucifixion". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Some Notes on Crucifixion" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- David W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian perceptions of crucifixion (Mohr Siebeck, 2008), pp. 86–89

- "Joe Zias, Crucifixion in Antiquity — The Anthropological Evidence". Joezias.com. Archived from the original on 2004-03-11. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- "The Bioarchaeology of Crucifixion". PoweredbyOsteons.org. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- "A multidisciplinary study of calcaneal trauma in Roman Italy:a possible case of crucifixion?". Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- "Crucifixion in the Fens: life & death in Roman Fenstanton" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- Retief FP, Cilliers L (December 2003). "The history and pathology of crucifixion". South African Medical Journal. 93 (12): 938–941. PMID 14750495.

- William Stroud; Sir James Young Simpson (1871). Treatise on the Physical Cause of the Death of Christ and Its Relation to the Principles and Practice of Christianity. Hamilton, Adams & Company. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Columbia University page of Pierre Barbet on Crucifixion". columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-12-11. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- Habermas, Gary; Kopel, Jonathan; Shaw, Benjamin C.F. (July 30, 2021). "Medical views on the death by crucifixion of Jesus Christ". Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 34 (6): 748–52. doi:10.1080/08998280.2021.1951096. PMC 8545147. PMID 34733010.

- Zugibe, Frederick T (1988). The cross and the shroud: a medical inquiry into the crucifixion. New York: Paragon House. ISBN 978-0-913729-75-5.

- Zugibe, Frederick T. (2005). The Crucifixion Of Jesus: A Forensic Inquiry. New York: M. Evans and Company. ISBN 978-1-59077-070-2.

- Maslen, Matthew; Piers D Mitchell (April 2006). "Medical theories on the cause of death in crucifixion". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (4): 185–188. doi:10.1177/014107680609900416. PMC 1420788. PMID 16574970.

- McGovern, Thomas W.; Kaminskas, David A.; Fernandes, Eustace S. (February 2023). "Did Jesus Die by Suffocation? An Appraisal of the Evidence". Linacre Quarterly. 90 (1): 64–79. doi:10.1177/00243639221116217. PMC 10009142. PMID 36923675.

- Edwards, WD; Gabel WJ; Hosmer FE (1986). "On the physical cause of death of Jesus Christ" (PDF). Journal of the American Medical Association. 255 (11): 1455–1463. doi:10.1001/jama.255.11.1455. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Davis, CT (1962). "The Crucifixion of Jesus. The Passion of Christ From a Medical Point of View". Arizona Medicine. 22: 182.

- Wijffels, F (2000). "Death on the cross: did the Turin Shroud once envelop a crucified body?". Br Soc Turin Shroud Newsl. 52 (3).

- Brenner, B (2005). "Did Jesus Christ die of pulmonary embolism?". J Thromb Haemost. 3 (9): 1–2. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01525.x. PMID 16102134. S2CID 38121158.

- The Life Of Flavius Josephus, 75.

- Stavros, Scolops (σταῦρός, σκόλοψ). The cross; Archived 2011-06-28 at the Wayback Machine encyclopedia Hellinica

- Translation by Aubrey de Selincourt. The original, "σανίδα προσπασσαλεύσαντες, ἀνεκρέμασαν ... Τούτου δὲ τοῦ Ἀρταύκτεω τοῦ ἀνακρεμασθέντος ...", is translated by Henry Cary (Bohn's Classical Library: Herodotus Literally Translated. London, G. Bell and Sons 1917, pp. 591–592) as: "They nailed him to a plank and hoisted him aloft ... this Artayctes who was hoisted aloft".

- W.W. How and J. Wells, A Commentary on Herodotus (Clarendon Press, Oxford 1912), vol. 2, p. 336

- See Mishnah, Sanhedrin 7:1, translated in Jacob Neusner, The Mishnah: A New Translation 591 (1988), supra note 8, at 595–596 (indicating that court ordered execution by stoning, burning, decapitation, or strangulation only)

- "Levi,Aramaic Testament of Levi 4Q541 column 6".

- Shi, Wenhua (2008). Paul's Message of the Cross As Body Language. Mohr Siebeck. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-16-149706-3.

- VanderKam, James C. (2012). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible. Eerdmans. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8028-6679-0.

- "Quintus Curtius Rufus, History of Alexander the Great of Macedonia 4.4.21". Archived from the original on 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Gabriel, Richard A. (2011). Hannibal. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-766-1.

- Liddell, Henry George (1855). A History of Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 302.

- Waterfield, Robin (2010). Polybius. The Histories. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-953470-8.

- Herodotus, Histories, 3.125 ("Having killed him in some way not fit to be told, Oroetes then crucified him")

- "Dialogue "To Marcia on Consolation", 6.20.3". googleusercontent.com (in Latin). The Latin Library.

- "Livy I.26 and the Supplicium de More Maiorum". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- "Apologia, IX, 1". Grtbooks.com. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- After quoting a poem by Maecenas that speaks of preferring life to death even when life is burdened with all the disadvantages of old age or even with acute torture ("vel acuta si sedeam cruce"), Seneca disagrees with the sentiment, saying death would be better for a crucified person hanging from the patibulum: "I should deem him most despicable had he wished to live to the point of crucifixion ... Is it worth so much to weigh down upon one's own wound, and hang stretched out from a patibulum? ... Is anyone found who, after being fastened to that accursed wood, already weakened, already deformed, swelling with ugly weals on shoulders and chest, with many reasons for dying even before getting to the cross, would wish to prolong a life-breath that is about to experience so many torments?" ("Contemptissimum putarem, si vivere vellet usque ad crucem ... Est tanti vulnus suum premere et patibulo pendere districtum ... Invenitur, qui velit adactus ad illud infelix lignum, iam debilis, iam pravus et in foedum scapularum ac pectoris tuber elisus, cui multae moriendi causae etiam citra crucem fuerant, trahere animam tot tormenta tracturam?" – Letter 101, 12–14)

- Titus Maccius Plautus Miles gloriosus Mason Hammond, Arthur M. Mack – 1997 p. 109, "The patibulum (in the next line) was a crossbar which the convicted criminal carried on his shoulders, with his arms fastened to it, to the place for ... Hoisted up on an upright post, the patibulum became the crossbar of the cross"

- "Appian • The Civil Wars – Book I". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- "Josephus, The War of the Jews, book 5, chapter 11".

- Fallow, Thomas Macall (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 506.

- Ball, DA (1989). "The crucifixion and death of a man called Jesus". Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association. 30 (3): 77–83. PMID 2651675.

- "Annales 2:32.2". Thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- "Annales 15:60.1". Thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- Flavius, Josephus. "Jewish War, Book V Chapter 11". ccel.org. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Mishna, Shabbath 6.10: see David W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion (Mohn Siebeck 2008 ISBN 978-3-16-149579-3), p. 182

- Wikisource:Of Consolation: To Marcia#XX.

- Licona, Michael (2010). The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach. InterVarsity Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-8308-2719-0. OCLC 620836940.

- Conway, Colleen M. (2008). Behold the Man: Jesus and Greco-Roman Masculinity. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-532532-4. (citing Cicero, pro Rabirio Perduellionis Reo 5.16 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine).

- "M. Tullius Cicero, Against Verres, actio 2, The Fifth Book of the Second Pleading in the Prosecution against Verres., section 170". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Koskenniemi, Erkki; Kirsi Nisula; Jorma Toppari (2005). "Wine Mixed with Myrrh (Mark 15.23) and Crurifragium (John 19.31–32): Two Details of the Passion Narratives". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 27 (4): 379–391. doi:10.1177/0142064X05055745. S2CID 170143075. Archived from the original on 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Encyclopædia Britannica Online: crucifixion". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- Dictionary of Images and Symbols in Counselling By William Stewart 1998 ISBN 1-85302-351-5, p. 120

- "Archaeology of the Bible". Bible-archaeology.info. Archived from the original on 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- Robison, John C. (June 2002). "Crucifixion in the Roman World: The Use of Nails at the Time of Christ". Studia Antiqua. 2.

- Zias, Joseph (1998). "Crucifixion in Antiquity: The Evidence". www.mercaba.org. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Matthew 27:35, Mark 15:24, Luke 23:34, John 19:23–25

- Zias, Joseph (2016-01-10). "Crucifixion in Antiquity: The Anthropological Evidence". Archived from the original on 2018-03-10. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Samuelsson, Gunnar (2013). Crucifixion in Antiquity: An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion. Mohr Siebeck. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-16-152508-7.

- Barth, Markus; Blanke, Helmut (2000). The Letter to Philemon: A New Translation with Notes and Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8028-3829-2.

- Barry, Strauss (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon & Schuster. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4391-5839-5.

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 18.3.4..

- Tacitus. Annals, Book 14, 42–45.

- Barry, Strauss (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-5839-5.

- Josephus (1990). Josephus: Essential Writings. Kregel Academic. p. 265.

- Barbet, P (1953). A Doctor at Calvary: The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ as Described by a Surgeon. New York: Doubleday Image Books. pp. 46–51.

- Fallow, Thomas Macall (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 506. Macall believes that the person would be given back his or her clothing following the scourging.

- Zias, Joseph. "Postscript – The Mel Gibson Controversy". JoeZias.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2004. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Justin Martyr Dialogue with Trypho, a Jew 91

- Irenaeus Against Heresies II.24

- Tertullian To the Nations I.12

- Barbet, 45; Zugibe, 57; Vassilios Tzaferis, "Crucifixion – The Archaeological Evidence," Biblical Archaeology Review 11.1 (Jan./Feb. 1985), 44–53 (p. 49)

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2014). How Jesus became God: The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee (First ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 133–165. ISBN 978-0-06-177818-6.

- Vogel, F.E. (2012). "Ṣalb". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6530.

- "Quran Surah Al-Maaida ( Verse 33 )". irebd.com.

- "Surah Al-Ma'idah [5]". Surah Al-Ma'idah [5].

- Kadri, Sadakat (2012). Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia ... macmillan. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-09-952327-7.

- Peters, Rudolph (2006). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: Theory and Practice from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38.

- "تصليب" [Taslib]. الموسوعة الفقهية (Encyclopedia of Fiqh) (in Arabic). Vol. 12. وزارة الأوقاف والشئون الإسلامية في دولة الكويت. 1988.

- "حرابة" [Hiraba]. الموسوعة الفقهية (Encyclopedia of Fiqh) (in Arabic). Vol. 17. وزارة الأوقاف والشئون الإسلامية في دولة الكويت. 1988.

- Anthony, Sean (2014). Crucifixion and Death as Spectacle: Umayyad Crucifixion in Its Late Antique Context. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Ewing, William A. (1994). The body: photographs of the human form. photograph by Felice Beato. Chronicle Books. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8118-0762-3.

- Clark Worswick (1979). Japan, photographs, 1854–1905. Knopf : distributed by Random House. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-394-50836-8.

- Moore, Charles Alexander; Aldyth V. Morris (1968). The Japanese mind: essentials of Japanese philosophy and culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8248-0077-2. OCLC 10329518.

- Schmidt, Petra (2002). Capital Punishment in Japan. Leiden: Brill. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-90-04-12421-9.

- "The Baptist Union: Latest News". baptist.org.uk.

- The Baptist Magazine, Volume 7. 1815. p. 67.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Bourke, Roger (2006). Prisoners of the Japanese: literary imagination and the prisoner-of-war experience. University of Queensland Press. p. 184 n.8. ISBN 978-0-7022-3564-1. OCLC 70257905.

- Overton, Iain (2001-04-17). "Revealed, the soldier who was crucified by Germans". International Express. p. 16.

- "The Crucified Soldier". Secret History. Season 9. Episode 5. 2002-07-04. Channel 4.

- Max Hastings, Armageddon: the Battle for Germany 1944–45, ISBN 978-0-330-49062-7

- Tzaferis, V (1970). "Jewish Tombs at and near Giv'at ha-Mivtar". Israel Exploration Journal. 20: 18–32.

- Haas, Nicu. "Anthropological observations on the skeletal remains from Giv'at ha-Mivtar", Israel Exploration Journal 20 (1–2), 1970: 38–59; Tzaferis, Vassilios. "Crucifixion – The Archaeological Evidence", Biblical Archaeology Review 11 (February, 1985): 44–53; Zias, Joseph. "The Crucified Man from Giv'at Ha-Mivtar: A Reappraisal", Israel Exploration Journal 35 (1), 1985: 22–27; Hengel, Martin. Crucifixion in the ancient world and the folly of the message of the cross (Augsburg Fortress, 1977). ISBN 0-8006-1268-X. See also Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome, by Donald G. Kyle p. 181, note 93

- by Paul L. Maier (1997). In the Fullness of Time. Kregel Publications. ISBN 978-0-8254-3329-0 – via Google Books.

- Zias J.; Sekeles, E. (1985). "The Crucified Man from Giv'at ha-Mivtar: A Reappraisal". Israel Exploration Journal. No. 35. pp. 22–27.

- Gualdi-Russo, E., Thun Hohenstein, U., Onisto, N. et al. A multidisciplinary study of calcaneal trauma in Roman Italy: a possible case of crucifixion?. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 1783–1791 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0631-9

- First example of Roman crucifixion in UK discovered in Cambridgeshire village, Arkeonews, 9 December 2021, https://arkeonews.net/first-example-of-roman-crucifixion-in-uk-discovered-in-cambridgeshire-village/

- Ingham D., Duhig C. Crucifixion in the Fens: life & death in Roman Fenstanton. British Archaeology, January–February 2022, pp. 18-29 https://www.archaeologyuk.org/resource/free-access-to-crucifixion-in-the-fens-life-and-death-in-roman-fenstanton.html

- Peters, Rudolph (2005). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-139-44534-4.

- AP (5 March 2013). "Saudi seven face crucifixion and firing squad for armed robbery". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Mar 18, Ali AlAhmed Published on. "The execution of the Saudi Seven – iPolitics". Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Qiblawi, Tamara; Alhenawi, Ruba (April 23, 2019). "Saudi Arabia executes 37 people, crucifying one, for terror-related crimes". CNN. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- "Saudi Arabia executes dozens on 'terrorism' charges". I24 News. April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- "Saudi Arabia must immediately halt execution of children – UN rights experts urge". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "When Beheading Won’t Do the Job, the Saudis Resort to Crucifixion". The Atlantic. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Iran's Islamic Criminal Law, Article 195" (PDF). nyccriminallawyer.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-28.

- "The Sanctions of the Islamic Criminal Law" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-26. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- "Case Study in Iranian Criminal System" (PDF). uni-muenchen.de. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- "Judicial Law on Retaliation, Stoning, Execution, Crucifixion, Hanging and Whipping, section 5, article 24" (PDF). mehr.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Tribune, Tom Masland, Chicago (14 October 1988). "MOSLEM CODE LOOMS IN SUDAN". chicagotribune.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Amnesty International, Document AFR 54/21/91". amnesty.org. 4 November 1991.

- "Death Penalty Worldwide: Sudan". Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- "Sudan: Imminent Execution/Torture/Unfair trial | Amnesty International". Web.amnesty.org. 2002-07-17. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- CBS News. "ISIS is killing, torturing and raping children in Iraq, U.N. says". Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- "Death and desecration in Syria: Jihadist group 'crucifies' bodies to send message". CNN/Associated Press. May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- Siegel, Jacob (30 April 2014). "Islamic Extremists Now Crucifying People in Syria—and Tweeting Out the Pictures". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

CORRECTION: This story misidentified the origin of a tweet and attributed it to an ISIS member when it actually came from Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, a student at Oxford University who has no affiliation with ISIS. We regret the error.

- Almasy, Steve (29 June 2014). "Group: ISIS 'crucifies' men in public in Syrian towns". CNN. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- "ISIS terror in and around Rojava, March-April 2014". Kurdistan Times. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- "Walking amongst sharp knives" (PDF). Karen Women Organization. February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Regime's human rights abuses go unpunished". Bangkok Post. 28 March 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Walker, Oksana Grytsenko Shaun (2014-01-31). "Ukrainian protester says he was kidnapped and tortured". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- Blair, David (2014-01-31). "Ukraine protest leader 'crucified and mutilated' after being abducted". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Ukraine activist Dmytro Bulatov 'kidnapped, tortured and left to die'". The Independent. 2014-01-31. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- Chivers, C. J. (2014-03-09). "A Kiev Question: What Became of the Missing?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Crucifixion for UAE murderers". The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- "UAE: Fear of imminent crucifixion and execution". Amnesty International. September 1997. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Crucifixion sentence is cancelled". The Irish Times. 8 September 1997. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- "UAE: Further information on fear of imminent crucifixion and execution". Amnesty International. September 1997. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Böhmer, Maria (2018-11-08). The Man Who Crucified Himself: Readings of a Medical Case in Nineteenth-Century Europe. BRILL. ISBN 9789004353602.

- "Religion-Mexico: The Passion According to Iztapalapa". IPS News. Archived from the original on 2009-12-26. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- Aragon, Ray John De (2006). The Penitentes of New Mexico: Hermanos de la Luz. Sunstone Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-86534-504-1.

- "Directory on popular piety and the liturgy. Principles and guidelines". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012.

- "Man Crucifies Himself Every Good Friday". Religious Freaks. 2006-04-12. Retrieved 2009-12-19. (dead link 6 April 2023)

- Cal, Ben (April 13, 2022). "Filipino penitent cancels 'crucifixion' anew due to Covid-19". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- Leilani, Junio (March 29, 2018). "DOH to penitents: Make sure nails, whips are sterilized". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120.

- Annals, 15.44.

- Rest, Friedrich (1982). Our Christian symbols. New York. p. 29. ISBN 0-8298-0099-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, III, xxxii.

- Sundermann, Werner (2009-07-20). "MANI". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- Friesen, Ilse E. (2006). The Female Crucifix: Images of St. Wilgefortis Since the Middle Ages. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-88920-939-8.

Eulalia... was stripped, beaten, tormented with iron hooks, had her bosom mutilated, was burnt with torches, and was portrayed as hanging on a rack or X-shaped cross

External links

- "Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion" by Frederick Zugibe

- Jesus's death on the cross, from a medical perspective

- "Crucifixion in antiquity – The Anthropological evidence" by Joe Zias at the Wayback Machine (archived February 12, 2012)

- "Dishonour, Degradation and Display: Crucifixion in the Roman World" by Philip Hughes

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Crucifixion

- Crucifixion of Joachim of Nizhny-Novgorod