Stowe Gardens

Stowe or Stowe Gardens, formerly Stowe Landscape Gardens, are extensive, Grade I listed gardens and parkland in Buckinghamshire, England. Largely created in the eighteenth century, the gardens at Stowe are arguably the most significant example of the English landscape garden style. Designed in several phases by Charles Bridgeman, William Kent, and Capability Brown, the gardens changed from a baroque park, to an increasingly naturalised landscape garden, commissioned by the estate's owners, in particular by Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham, his nephew Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple, and his nephew George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham.

| Stowe | |

|---|---|

The Palladian Bridge | |

| |

| Type | Landscaped garden |

| Location | Buckinghamshire, England |

| Coordinates | 52°01′48″N 01°00′54″W |

| Website | Stowe |

| Official name | Stowe |

| Designated | 30 August 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1000198 |

The gardens are notable for the scale, the design, the size and the number of monuments set across the designed landscape, as well as for the fact they have been a tourist attraction for over three hundred years. The English landscape garden at Stowe has Grade I listed status, and many of the monuments in the property have their own, additional, Grade I listing. These include: the Corinthian Arch, the Temple of Venus, the Palladian Bridge, the Gothic Temple, the Temple of Ancient Virtue, the Temple of British Worthies, the Temple of Concord and Victory, the Queen's Temple, Doric Arch, the Oxford Bridge, amongst others.

The majority of the gardens, along with part of the park, passed into the ownership of the National Trust in 1989, whilst Stowe House, the home of Stowe School, is under the care of the Stowe House Preservation Trust. The parkland surrounding the gardens is open 365 days a year.

History

Origins

The Stowe gardens and estate are located close to the village of Stowe in Buckinghamshire, England.[1] John Temple, a wealthy wool farmer, purchased the manor and estate in 1589. Subsequent generations of Temples inherited the estate, but it was with the succession of Sir Richard Temple that the gardens began to be developed, after the completion of a new house in 1683.[1]

Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham, inherited the estate in 1697, and in 1713 was given the title Baron Cobham. During this period, both the house and the garden were redesigned and expanded, with leading architects, designers and gardeners employed to enhance the property.[1] The installation of a variety of temples and classical features was illustrated the Temple family's wealth and status. The temples are also considered as a humorous reference to the family motto: TEMPLA QUAM DILECTA ('How beautiful are the Temples').[2]

1690s to 1740s

In the 1690s, Stowe had a modest early Baroque parterre garden, but it has not survived, as it was altered and adapted as the gardens were progressively remodelled.[3] Within a relatively short time, Stowe became widely renowned for its magnificent gardens created by Lord Cobham. Created in three main phases, the gardens at Stowe show the development of garden design in 18th-century England. They are also the only gardens where Charles Bridgeman, William Kent, and Capability Brown all made significant contributions to the character and design.[4]

From 1711 to c.1735 Charles Bridgeman was the garden designer,[5] whilst John Vanbrugh was the architect from c.1720 until his death in 1726.[6] They designed an English Baroque park, inspired by the work of London, Wise and Switzer. After Vanbrugh's death James Gibbs took over as architect in September 1726. He also worked in the English Baroque style.[7] Bridgeman was notable for the use of canalised water at Stowe.[8]

In 1731 William Kent was appointed to work with Bridgeman, whose last designs are dated 1735. After Bridgeman, Kent took over as the garden designer.[9] Kent had already created the noted garden at Rousham House, and he and Gibbs built temples, bridges, and other garden structures, creating a less formal style of garden.[10] Kent's masterpiece at Stowe is the innovative Elysian Fields, which were "laid out on the latest principles of following natural lines and contours".[11] With its Temple of Ancient Virtue that looks across to his Temple of British Worthies, Kent's architectural work was in the newly fashionable Palladian style.[12]

In March 1741, Capability Brown was appointed head gardener and he lived in the East Boycott Pavilion.[13] He had first been employed at Stowe in 1740, to support work on the water schemes on site.[14] Brown worked with Gibbs until 1749 and with Kent until the latter's death in 1748. Brown departed in the autumn of 1751 to start his independent career as a garden designer.[15] At that time, Bridgeman's octagonal pond and 11-acre (4.5 ha) lake were extended and given a "naturalistic" shape. A Palladian bridge was added in 1744, probably to Gibbs's design. Brown also reputedly contrived a Grecian Valley which, despite its name, was an abstract composition of landform and woodland.[16] He also developed the Hawkwell Field, with Gibbs's most notable building, the Gothic Temple, within.[17] The Temple is one of the properties leased from the National Trust by The Landmark Trust, who maintain it as a holiday home.[18] As Loudon remarked in 1831, "nature has done little or nothing; man a great deal, and time has improved his labours".[19]

1740s to 1760s

Earl Temple, who had inherited Stowe from his uncle Lord Cobham, turned to a garden designer called Richard Woodward after Brown left. Woodward had worked at Wotton House, the Earl's previous home.[20] The work of naturalising the landscape started by Brown was continued under Woodward and was accomplished by the mid-1750s.[11]

At the same time Earl Temple turned his attention to the various temples and monuments. He altered several of Vanburgh's and Gibbs's temples to make them conform to his taste for Neoclassical architecture. To accomplish this he employed Giovanni Battista Borra from July 1750 to c.1760.[21][22] Also at this time several statues and temples were relocated within the garden, including the Fane of Pastoral Poetry.[23]

Earl Temple made further alterations in the gardens from the early 1760s with alteration to both planting and structure, and several older structures were removed, including the Witches House. Several designs for this period are attributed to his cousin Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford.[22] Camelford's most notable design was the Corinthian Arch.[24]

1770s onwards

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_855893.jpg.webp)

Famed as a highly fashionable garden, by 1777 some visitors, such as the 2nd Viscount Palmerston, complained that the gardens were "much behind the best modern ones in points of good taste".[25]

The next owner of Stowe, the Marquess of Buckingham, made relatively few changes to the gardens, as his main contribution to the Stowe scheme was the completion of Stowe House's interior.[26] Vincenzo Valdrè was his architect and built a few new structures such as The Menagerie, with its formal garden and the Buckingham Lodges at the southern end of the Grand Avenue, and most notably the Queen's Temple.[27]

19th-century Stowe

The last significant changes to the gardens were made by the next two owners of Stowe, the 1st and 2nd Dukes of Buckingham and Chandos. The former succeeded in buying the Lamport Estate in 1826, which was immediately to the east of the gardens, adding 17 acres (6.9 ha) to the south-east of the gardens to form the Lamport Gardens.[28]

From 1840 the 2nd Duke's gardener Mr Ferguson created rock structures and water features in the new Lamport Gardens. The architect Edward Blore was also employed to build the Lamport Lodge and Gates as a carriage entrance, and also remodelled the Water Stratford Lodge at the start of the Oxford Avenue.[27]

In 1848 the 2nd Duke was forced to sell the house, the estate and the contents in order to begin to pay off his debts. The auction by Christie's made the name of the auction house.[29] In 1862, the third Duke of Buckingham and Chandos returned to Stowe and began to repair several areas of the gardens, including planting avenues of trees. In 1868 the garden was re-opened to the public.[30]

20th century

The remaining estate was sold in 1921 and 1922. In 1923 Stowe School was founded, which saved the house and garden from destruction.[29] Until 1989 the landscape garden was owned by Stowe School, who undertook some restoration work, including the development of a restoration plan in the 1930s. The first building to be restored was the Queen's Temple, repairs to which were funded by a public appeal launched by the future Edward VIII. In the 1950s repairs were made to the Temple of Venus, the Corinthian Arch and the Rotondo. Stowe Avenue was replanted in 1960.[31]

In the 1960s significant repairs were made to buildings, such as the Lake Pavilions and the Pebble Alcove. Other works included replanting several avenues, repairs to two-thirds of the buildings, and the reclamation of six of the lakes (only the Eleven Acre Lake was not tackled). As a result of this the school was recognised for its contribution to conservation and heritage with awards in 1974 and 1975.[31]

The National Trust first became significantly involved in Stowe in 1965, when John Workman was invited to compile a plan for restoration.[32] In 1967, 221 acres were covenanted to the National Trust and in 1985 the trust purchased Oxford Avenue, the first time it had bought land to enhance a site not under its ownership.[33] In 1989 much of the garden and the park was donated to the National Trust, after generous donations from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and an anonymous benefactor, which enabled an endowment for repairs to be created.[33] In 1993 the National Trust successfully completed an appeal for £1 million, with the aim of having the garden restored by 2000. Parallel to fund-raising, extensive garden, archaeological and biological surveys were undertaken.[32] Further repairs were undertaken to many monuments in the 1990s.[34] The Stowe Papers, some 350,000 documents relating to the estate, are in the collection of the Huntington Library.[32]

21st century

In 2012 the restoration of the historic New Inn was finished, providing enhanced visitor services.[35][36] In 2015, the National Trust began a further programme of restoration, which included the recreation of the Queens Theatre, the return of many statues to former locations in the Grecian Valley, and the return of the Temple of Modern Virtue to the Elysian Fields.[37]

Accommodating the requirements of a 21st-century school within a historic landscape continues to create challenges. In the revised Buckinghamshire, in the Pevsner Buildings of England series published in 2003, Elizabeth Williamson wrote of areas of the garden being "disastrously invaded by school buildings."[38][lower-alpha 1] In 2021, plans for a new Design, Technology and Engineering block in Pyramid Wood provoked controversy. The school's plans were supported by the National Trust but opposed by Buckinghamshire County Council’s own planning advisors, as well as a range of interest groups including The Gardens Trust.[40] Despite objections from the council’s independent advisor,[41] and an appeal to the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, the plans were approved in 2022.[42]

Layout

Approaching Stowe Gardens

In 2012, with the renovation and re-opening of the New Inn, visitors to Stowe Gardens have returned to using the historic entrance route to the site which was used by tourists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Most will drive between the Buckingham Lodges, before approaching the site along the Grand Avenue and turning right in front of the Corinthian Arch.[43]

Significant monuments on the route in, include:

The Buckingham Lodges

The Buckingham Lodges are 2.25 miles south-southeast of the centre of the House. Probably designed by Vincenzo Valdrè and dated 1805, they flank the southern entrance to the Grand Avenue.[44]

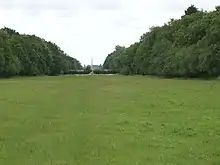

The Grand Avenue

The Grand Avenue, from Buckingham to the south and the Oxford Avenue from the south-west, which leads to the forecourt of the house. The Grand Avenue was created in the 1770s; it is 100 ft (30 m) in width and one and half miles in length, and was lined originally with elm trees. The elms succumbed in the 1970s to Dutch elm disease and were replaced with alternate beech & chestnut trees.[45]

The Corinthian Arch

Designed in 1765 by Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford, Lord Temple's cousin, the arch is built from stone and is 60 ft (18 m) in height and 60 ft (18 m) wide. It is modelled on ancient Roman triumphal arches. This is located at the northern end of the Grand Avenue 0.8 miles south-southeast of the centre of the House and is on the top of a hill. The central arch is flanked on the south side by paired Corinthian pilasters and on the north side by paired Corinthian engaged columns. The arch contains two four-storey residences. The flanking Tuscan columns were added in 1780.[46]

The New Inn

Situated about 330 ft (100 m) to the east of the Corinthian Arch, the inn was built in 1717 specifically to provide accommodation for visitors to the gardens. It was expanded and rebuilt in several phases.[47] The inn housed a small brewery, a farm and dairy. It closed in the 1850s, then being used as a farm, smithy and kennels for deer hounds.[48]

The building was purchased in a ruinous condition by the National Trust in 2005. In 2010 work started on converting it into the new visitor centre, and since 2011 this has been the entrance for visitors to the gardens.[49] Visitors had formerly used the Oxford Gates. The New Inn is linked by the Bell Gate Drive to the Bell Gate next to the eastern Lake Pavilion, so called because visitors used to have to ring the bell by the gate to gain admittance to the property.[47]

Ha-ha

The main gardens, enclosed within the ha-has (sunken or trenched fences) over four miles (6 km) in length, cover over 400 acres (160 ha).[50]

Gallery of features when approaching Stowe

The Buckingham Lodges

The Buckingham Lodges The Grand Avenue looking north towards the Corinthian Arch and Buckingham

The Grand Avenue looking north towards the Corinthian Arch and Buckingham The Corinthian Arch

The Corinthian Arch The New Inn

The New Inn The ha-ha that surrounds the park

The ha-ha that surrounds the park Octagon Lake with Stowe House

Octagon Lake with Stowe House

Octagon lake

One of the first areas of the garden that visitors may encounter is the Octagon Lake and the features associated with it. The lake was originally designed as a formal octagonal pool, with sharp corners, as part of the seventeenth century formal gardens. Over the years, the shape of the pond was softened, gradually harmonising it within Stowe's increasingly naturalistic landscape.[51]

Monuments and structures in this area include:

The Chatham Urn

This is a copy of the large stone urn known as the Chatham Vase carved in 1780 by John Bacon. It was placed in 1831 on a small island in the Octagon Lake. It is a memorial to William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham former Prime Minister, who was a relative of the Temple family. The original was sold in 1848 and is now at Chevening House.[52]

Congreve's Monument

Built of stone designed by Kent in 1736, this is a memorial to the playwright William Congreve.[52] It is in the form of a pyramid with an urn carved on one side with Apollo's head, pan pipes and masks of comedy and tragedy; the truncated pyramid supports the sculpture of an ape looking at itself in a mirror, beneath are these inscriptions:

Vitae imitatio Consuetudinis speculum Comoedia |

Comedy is the imitation of life, and the glass of fashion |

Ingenio Acri, faceto, expolito, Moribusque Urabnis |

In the year 1736, COBHAM erected this poor consolation of |

The Lake Pavilions

These pavilions have moved location during their history. They were designed by Vanbrugh in 1719, they are on the edge of the ha-ha flanking the central vista through the park to the Corinthian Arch. They were moved further apart in 1764 and their details made neo-classical by the architect Borra. Raised on a low podium they are reached by a flight of eight steps, they are pedimented of four fluted Doric columns in width by two in depth, with a solid back wall and with coffered plaster ceiling. Behind the eastern pavilion is the Bell Gate. This was used by the public when visiting the gardens in the 18th and 19th centuries.[53]

The Artificial Ruins & The Cascade

Constructed in the 1730s the cascade links the Eleven Acre Lake which is higher with the Octagon Lake. The ruins are a series of arches above the cascade purposefully built to look ruinous.[54][55]

The Wooden Bridge

This crosses the mouth of the River Styx where it emptied into the Octagon Lake. Rebuilt in 2012 by the National Trust in oak, it recreates a long lost bridge.[26]

The Pebble Alcove

Built of stone before 1739 probably to the designs of Kent. It takes the form of an exedra enclosed by a stone work surmounted by a pediment. The exedra is decorated with coloured pebbles, including the family coat of arms below which is the Temple family motto TEMPLA QUAM DELECTA (How Beautiful are thy Temples).[56]

Gallery of features near the Octagon Lake

The Chatham Urn

The Chatham Urn.jpg.webp) Congreve's Monument

Congreve's Monument The Western Lake Pavilion

The Western Lake Pavilion The Artificial Ruins and Cascade

The Artificial Ruins and Cascade Wooden Bridge

Wooden Bridge The Pebble Alcove

The Pebble Alcove

South vista

The south vista includes the tree-flanked sloping lawns to the south of the House down to the Octagon Lake and a mile and a half beyond to the Corinthian Arch beyond which stretches the Grand Avenue of over a mile and a half to Buckingham. This is the oldest area of the gardens. There were walled gardens on the site of the south lawn from the 1670s that belonged to the old house. These gardens were altered in the 1680s when the house was rebuilt on the present site. They were again remodelled by Bridgeman from 1716.[57] The lawns with the flanking woods took on their current character from 1741 when 'Capability' Brown re-landscaped this area.[58]

The buildings in this area are:

The Doric Arch

Built of stone erected in 1768 for the visit of Princess Amelia, probably to the design of Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford, is a simple arch flanked by fluted Doric pilasters, with an elaborate entablature with triglyphs and carved metopes supporting a tall attic. This leads to the Elysian fields.[59]

Apollo and the Nine Muses

Arranged in a semicircle near the Doric Arch there used to be statues of Apollo and the Nine Muses removed sometime after 1790.[60] These sculptures were created by John Nost and were originally positioned along the south vista.[61] In 2019 the ten plinths 5 each side of the Doric Arch were recreated,[lower-alpha 2] and statues of the Nine Muses placed on them.[62]

Statue of George II

%252C_Stowe_-_Buckinghamshire%252C_England_-_DSC07039.jpg.webp)

On the western edge of the lawn, the statue was rebuilt in 2004 by the National Trust.[63] This is a monument to King George II, originally built in 1724 before he became king.[64] The monument consists of an unfluted Corinthian column on a plinth over 30 ft (9.1 m) high that supports the Portland stone sculpture of the King which is a copy of the statue sold in 1921.[63] The pillar has this inscription from Horace's Ode 15, Book IV:

Crevere Vires, Famaque & Imperi |

(Under the care of Cæsar's scepter'd hand, |

The Elysian fields

.jpg.webp)

The Elysian Fields is an area to the immediate east of the South Vista; designed by William Kent, work started on this area of the gardens in 1734.[65] The area covers about 40 acres (16 ha).[66] It consists of a series of buildings and monuments surrounding two narrow lakes, called the River Styx, which step down to a branch of the Octagon Lake.[67] The banks are planted with deciduous and evergreen trees.[67] The adoption of the name alludes to Elysium, and the monuments in this area are to the 'virtuous dead' of both Britain and ancient Greece.[68]

The buildings in this area are:

Saint Mary's Church

In the woods between the House and the Elysian Fields is Stowe parish church. This is the only surviving structure from the old village of Stowe. Dating from the 14th century, the building consists of a nave with aisles and a west tower, a chancel with a chapel to the north and an east window c. 1300 with reticulated tracery.[69]

Lancelot "Capability" Brown was married in the church in 1744.[70] The church contains a fine Laurence Whistler etched glass window in memory of The Hon. Mrs. Thomas Close-Smith of Boycott Manor, eldest daughter of the 11th Lady Kinloss, who was the eldest daughter of the 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos. Thomas Close-Smith himself was the High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire in 1942, and died in 1946.[71] Caroline Mary, his wife, known as May, died in 1972.[72]

The Temple of Ancient Virtue

Built in 1737 to the designs of Kent, in the form of a Tholos, a circular domed building surrounded by columns.[70] In this case they are unfluted Ionic columns, 16 in number, raised on a podium. There are twelve steps up to the two arched doorless entrances. Above the entrances are the words Priscae virtuti (to Ancient Virtue).[73] Within are four niches one between the two doorways. They contain four life size sculptures (plaster copies of the originals by Peter Scheemakers paid for in 1737, they were sold in 1921). They are Epaminondas (general), Lycurgus (lawmaker), Homer (poet) and Socrates (philosopher).[74]

The Temple of British Worthies

Designed by Kent and built 1734–1735. Built of stone, it is a curving roofless exedra with a large stone pier in the centre surmounted by a stepped pyramid containing an oval niche that contains a bust of Mercury, a copy of the original. The curving wall contains six niches either side of the central pier, with further niches on the two ends of the wall and two more behind.[75] At the back of the Temple is a chamber with an arched entrance, dedicated to Signor Fido, a greyhound.[76][lower-alpha 3]

The niches are filled by busts, half of which were carved by John Michael Rysbrack for a previous building in the gardens. They portray John Milton, William Shakespeare, John Locke, Sir Isaac Newton, Sir Francis Bacon, Elizabeth I, William III and Inigo Jones. The other eight are by Peter Scheemakers, which were commissioned especially for the Temple. These represent Alexander Pope, Sir Thomas Gresham, King Alfred the Great, The Black Prince, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake, John Hampden and Sir John Barnard (Whig MP and opponent of the Whig Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole).[77]

The choice of who was considered a 'British Worthy' was very much influenced by the Whig politics of the family, the chosen individuals falling into two groups, eight known for their actions and eight known for their thoughts and ideas.[78] The only woman to be included was Elizabeth I.[79] The inscription above her bust, which praises her leadership, reads:

Who confounded the Projects, and destroyed the Power, that threatened to oppress the Liberties of Europe... and, by a wise, a moderate, and a popular Government, gave Wealth, Security, and Respect to England

The Shell Bridge

Designed by Kent, and finished by 1739, is actually a dam disguised as a bridge of five arches and is decorated with shells.[80][81]

The Grotto

Probably designed by Kent in the 1730s, is located at the head of the serpentine 'river Styx' that flows through the Elysian Fields. There are two pavilions, one ornamented with shells the other with pebbles and flints. In the central room is a circular recess in which are two basins of white marble.[82] In the upper is a marble statue of Venus rising from her bath, and water falls from the upper into the lower basin, there passing under the floor to the front, where it falls into the river Styx. A tablet of marble is inscribed with these lines from Milton:[83]

Goddess of the silver wave,

To thy thick embower'd cave,

To arched walks, and twilight groves,

And shadows brown, which Sylvan loves

When the sun begins to fling

His flaring beams, me, Goddess, bring.

The Seasons Fountain

Probably erected in 1805, built from white statuary marble. Spring water flows from it, and the basic structure appears to be made from an 18th-century chimneypiece.[84] It used to be decorated with Wedgwood plaques of the four seasons and had silver drinking cups suspended on either side.[85] it was the first structure to be reconstructed under National Trust ownership.[84]

The Grenville Column

Originally erected in 1749 near the Grecian Valley, it was moved to its present location in 1756; Earl Temple probably designed it.[86] It commemorates one of Lord Cobham's nephews, Captain Thomas Grenville RN.[87] He was killed in 1747 while fighting the French off Cape Finisterre aboard HMS Defiance under the command of Admiral Anson.[86]

The monument is based on an Ancient Roman naval monument, a rostral column, one that is carved with the prows of Roman galleys sticking out from the shaft. The order used is Tuscan, and is surmounted by a statue of Calliope holding a scroll inscribed Non nisi grandia canto (Only sing of heroic deeds); there is a lengthy inscription in Latin added to the base of the column after it was moved.[86]

The Cook Monument

Built in 1778 as a monument to Captain James Cook; it takes the form of a stone globe on a pedestal. It was moved to its present position in 1842.[84] The pedestal has a carved relief of Cook's head in profile and the inscription Jacobo Cook/MDCCLXXVIII.[88]

The Gothic Cross

Erected in 1814 from Coade stone on the path linking the Doric Arch to the Temple of Ancient Virtue. It was erected by the 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos as a memorial to his mother Lady Mary Nugent.[87] It was demolished in the 1980s by a falling elm tree. The National Trust rebuilt the cross in 2016 using several of the surviving pieces of the monument.[89]

The Marquess of Buckingham's Urn

Sited behind the Temple of British Worthies, erected in 1814 by the 1st Duke in memory of his father, the urn was moved to the school precincts in 1931. A replica urn was created and erected in 2018.[90]

Gallery of features around the Elysian fields

Saint Mary's Church

Saint Mary's Church The Temple of Ancient Virtue

The Temple of Ancient Virtue The Temple of British Worthies

The Temple of British Worthies Epitaph to Signior Fido at the rear of the Temple of British Worthies

Epitaph to Signior Fido at the rear of the Temple of British Worthies The Shell Bridge

The Shell Bridge Looking out from the Grotto

Looking out from the Grotto.jpg.webp) The Seasons Fountain

The Seasons Fountain The Grenville Column

The Grenville Column The Cook Monument

The Cook Monument

Hawkwell Field

Hawkwell Field lies to the east of the Elysian Fields, and is also known as The Eastern Garden. This area of the gardens was developed in the 1730s & 1740s, an open area surrounded by some of the larger buildings all designed by James Gibbs.[91]

The buildings in this area are:

The Queen's Temple

Originally designed by Gibbs in 1742 and was then called the Lady's Temple.[92] This was designed for Lady Cobham to entertain her friends. But the building was extensively remodelled in 1772–1774 to give it a neo-classical form.[93]

Further alterations were made in 1790 by Vincenzo Valdrè.[94] These commemorated the recovery of George III from madness with the help of Queen Charlotte after whom the building was renamed.[95]

The main floor is raised up on a podium, the main façade consists of a portico of four fluted Composite columns, these are approached by a balustraded flight of steps the width of the portico. The facade is wider than the portico, the flanking walls having niches containing ornamental urns. The large door is fully glazed.[92]

The room within is the most elaborately decorated of any of the garden's buildings. The Scagliola Corinthian columns and pilasters are based on the Temple of Venus and Roma, the barrel-vaulted ceiling is coffered. There are several plaster medallions around the walls, including: Britannia Deject, with this inscription Desideriis icta fidelibus Quaerit Patria Caesarem (For Caesar's life, with anxious hopes and fears Britannia lifts to Heaven a nation's tears); Britannia with a palm branch sacrificing to Aesculapius with this inscription O Sol pulcher! O laudande, Canam recepto Caesare felix (Oh happy days! with rapture Britons sing the day when Heavenrestore their favourite King!); Britannia supporting a medallion of the Queen with the inscription Charlottae Sophiae Augustae, Pietate erga Regem, erga Rempublicam Virtute et constantia, In difficillimis temporibus spectatissimae D.D.D. Georgius M. de Buckingham MDCCLXXXIX. (To the Queen, Most respectable in the most difficult moments, for her attachment and zeal for the public service, George Marquess of Buckingham dedicates this monument).[92]

Other plaster decoration on the walls includes: 1. Trophies of Religion, Justice and Mercy, 2. Agriculture and Manufacture, 3. Navigation and Commerce and 4. War.[92] Almost all the decoration was the work of Charles Peart except for the statue of Britannia by Joseph Ceracchi.

In 1842 the 2nd Duke of Buckingham inserted in the centre of the floor the Roman mosaic found at nearby Foscott.[92] The Temple has been used for over 40 years by the school as its Music School.[94]

The Gothic Temple

Designed by James Gibbs in 1741 and completed about 1748, this is the only building in the gardens built from ironstone, all the others use a creamy-yellow limestone. The building is triangular in plan of two storeys with a pentagonal shaped tower at each corner, one of which rises two floors higher than the main building, while the other two towers have lanterns on their roofs. Above the door is a quote from Pierre Corneille's play Horace: Je rends grace aux Dieux de n'estre pas Roman (I thank the gods I am not a Roman).[96]

The interior includes a circular room of two storeys covered by a shallow dome that is painted to mimic mosaic work including shields representing the Heptarchy. Dedicated 'To the Liberty of our Ancestors'. To quote John Martin Robinson: 'to the Whigs, Saxon and Gothic were interchangeably associated with freedom and ancient English liberties: trial by jury (erroneously thought to have been founded by King Alfred at a moot on Salisbury Plain), Magna Carta, parliamentary representation, all the things which the Civil War and Glorious Revolution had protected from the wiles of Stuart would-be absolutism, and to the preservation of which Lord Cobham and his 'Patriots' were seriously devoted.[97]

The Temple was used in the 1930s by the school as the Officer Training Corps armoury.[98] It is now available as a holiday let through the Landmark Trust.[99]

The Temple of Friendship

Built of stone in 1739 to the designs of Gibbs.[100] It is located in the south-east corner of the garden. Inscribed on the exterior of the building is AMICITIAE S (sacred to friendship). It was badly damaged by fire in 1840 and remains a ruin.[101]

Built as a pavilion to entertain Lord Cobham's friends it was originally decorated with murals by Francesco Sleter including on the ceiling Britannia, the walls having allegorical paintings symbolising friendship, justice and liberty. There was a series of ten white marble busts on black marble pedestals around the walls of Cobham (this bust with that of Lord Westmoreland is now in the V&A Museum) and his friends: Frederick, Prince of Wales; Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield; George Lyttelton, 1st Baron Lyttelton; Thomas Fane, 8th Earl of Westmorland; William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham; Allen Bathurst, 1st Earl Bathurst; Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple; Alexander Hume-Campbell, 2nd Earl of Marchmont; John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower. Dated 1741, three were carved by Peter Scheemakers: Cobham, Prince Frederick & Lord Chesterfield, the rest were carved by Thomas Adye. All the busts were sold in 1848.[101]

The building consisted of a square room rising through two floors surmounted by a pyramidal roof with a lantern. The front has a portico of four Tuscan columns supporting a pediment, the sides have arcades of one arch deep by three wide also supporting pediments. The arcades and portico with the wall behind are still standing.[101]

The Palladian Bridge

This is a copy of the bridge at Wilton House in Wiltshire, which was itself based in a design by Andrea Palladio. The main difference from the Wilton version, which is a footbridge, is that the Stowe version is designed to be used by horse-drawn carriages so is set lower with shallow ramps instead of steps on the approach. It was completed in 1738 probably under the direction of Gibbs. Of five arches, the central wide and segmental with carved keystone, the two flanking semi-circular also with carved keystones, the two outer segmental. There is a balustraded parapet, the middle three arches also supporting an open pavilion. Above the central arch this consists of colonnades of four full and two half columns of unfluted Roman Ionic order. Above the flanking arches there are pavilions with arches on all four sides. These have engaged columns on their flanks and ends of the same order as the colonnade which in turn support pediments. The roof is of slate, with an elaborate plaster ceiling. It originally crossed a stream that emptied from the Octagon Lake, and when the lake was enlarged and deepened, made more natural in shape in 1752, this part of the stream became a branch of the lake.[102]

The Saxon Deities

These are sculptures by John Michael Rysbrack of the seven deities that gave their names to the days of the week.[103] Carved from Portland stone in 1727. They were moved to their present location in 1773. (The sculptures are copies of the originals that were sold in 1921–1922).[104] For those, like the Grenville family, who followed Whig politics, the terms 'Saxon' and 'Gothic' represented supposedly English liberties, such as trial by jury.[97]

The sculptures are arranged in a circle. Each sculpture (with the exception of Sunna a half length sculpture) is life size, the base of each statue has a Runic inscription of the god's name, and stands on a plinth. They are: Sunna (Sunday), Mona (Monday), Tiw (Tuesday), Woden (Wednesday), Thuner (Thursday), Friga (Friday) and a Saxon version of Seatern (Saturday).[104]

The original Sunna & Thuner statues are in the V&A Museum, the original Friga stood for many years in Portmeirion but was sold at auction in 1994 for £54,000, the original Mona is in the Buckinghamshire County Museum.[105]

Gallery of features in the Hawkwell Field

The Queen's Temple

The Queen's Temple The Gothic Temple

The Gothic Temple Interior of the Gothic Temple

Interior of the Gothic Temple The Temple of Friendship

The Temple of Friendship Palladian Bridge

Palladian Bridge Ceiling of the Palladian Bridge

Ceiling of the Palladian Bridge The original Thuner, now in the V & A Museum

The original Thuner, now in the V & A Museum

The Grecian valley

Is to the north of the Eastern Garden. Designed by Capability Brown and created from 1747 to 1749, this is Brown's first known landscape design. An L-shaped area of lawns covering about 60 acres (24 ha), was formed by excavating 23,500 cu yd (18,000 m3) of earth by hand and removed in wheelbarrows with the original intention of creating a lake. Mature Lime and Elm trees were transplanted from elsewhere on the estate to create a mature landscape. Other tree species that Brown used in this and other areas of the gardens include: cedar, yew, beech, sycamore, larch & Scots pine.[106] As of 2020 there was large London plane tree in the Grecian Valley, that was potentially planted by Capability Brown.[107]

The buildings in this area are:

Temple of Concord and Victory

The designer of this, the largest of the garden buildings, is unknown, although both Earl Temple and Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford have been suggested as the architect. It is a highly significant, since it is the first building in England whose design intentionally imitate Greek architecture; it was originally known as the 'Grecian Temple'.[108] Earl Temple was a member of the Society of Dilettanti, a group made up of members of the aristocracy who pursued the study of art and architecture.[109]

Built from stone, between 1747 and 1749, the building is located where the two legs of the valley meet. It is raised on a podium with a flight of steps up to the main entrance, the cella and pronaos is surrounded by a peristyle of 28 fluted Roman Ionic columns, ten on the flanks and six at each end.[110] The main pediment contains a sculpture by Peter Scheemakers of Four-Quarters of the World bringing their Various Products to Britannia.[111] There are six statues acroterion of cast lead painted to resemble stone on both the east and west pediments. In the frieze of the entablature are the words CONCORDIAE ET VICTORIAE.[110]

The sculpture on the building dates from the 1760s when it was converted into a monument to the British victory in the Seven Years' War.[108] The ceiling of the peristyle is based on an engraving by Robert Wood of a ceiling in Palmyra. Within the pronaos and cella are 16 terracotta medallions commemorating British Victories in the Seven Years' War, these were designed by James "Athenian" Stuart, each one is inscribed with the name of the battle: Quebec; Martinico & c.; Louisbourg; Guadeloupe & c.; Montreal; Pondicherry & c.; the naval battle of Belleisle; the naval Battle of Lagos; Crevelt & Minden; Fellinghausen; Goree and Senegal; Crown Point, Niagara and Quesne; Havannah and Manila; Beau Sejour, Cherburgh and Belleisle.[110]

The wooden doors are painted a Prussian blue with gilded highlights on the mouldings. Above the door is an inscription by Valerius Maximus:

Quo Tempore Salus eorum in ultimas Ausustias deducta |

The Times with such alarming Dangers fraught |

The interior end wall of the cella has an aedicule containing a statue of Liberty.[112] Above is this inscription:

Candidis autem animis voluptatem praebuerint in |

A sweet sensation touches every breast of candour's generous sentiment possest, |

The six statues from the roof were sold in 1921.[113] When the school built its chapel in the late 1920s, 16 of the 28 columns from this Temple were moved to the new building, being replaced with plain brickwork. From 1994 to 1996 the National Trust undertook restoration works to create replacement columns with which to restore the Temple.[112]

The Fane of Pastoral Poetry

Located in a grove of trees at the eastern end of the Grecian Valley, at the north-east corner of the gardens, the structure is a small belvedere designed by James Gibbs in 1729.[114] It was moved to its present position in the 1760s; it originally stood where Queen Caroline's statue stands.[115] It is square in plan with chamfered corners that, built of stone, each side is an open arch, herma protrude from each chamfered corner. It is surmounted by an octagonal lead dome.[114]

The Circle of the Dancing Faun

Located near the north-east end of the valley near the Fane of Pastoral Poetry, the Dancing Faun commanded the centre of a circle of five sculptures of shepherds and shepherdesses, all of the sculptures had been sold. Two of these statues were located in Buckingham and restored in 2009 to their original place in the garden. In 2016 the Faun supported by the so-called Saxon Altar and the other three statues were recreated.[116]

The Cobham Monument

To the south of the Grecian Valley is the tallest structure in the gardens rising 115 ft.[117] Built 1747–49 of stone, probably designed by Brown, who adapted a design by Gibbs.[118] It consists of a square plinth with corner buttresses surmounted by Coade stone lions holding shields added in 1778. The column itself is octagonal with a single flute on each face, with a molded doric capital and base. On which is a small belvedere of eight arches with a dome supporting the sculpture of Lord Cobham, the probable sculptor of which was Peter Scheemakers.[117]

The present statue is a recreation made in 2001 after the original was struck by lightning in 1957.[118] A spiral staircase rises through the column to the belvedere providing an elevated view of the gardens. Lord Cobham's Walk is a tree-lined avenue that stretches from the Pillar north-east to the edge of the gardens.[114]

Statues surrounding the Grecian Valley

The National Trust is creating copies of the statues that used to be found around the edge of the Grecian Valley, and is adding them as and when funds can be raised to cover the cost.[37] The sculptures included Samson and the Philistine recreated in 2015, and several of the twelve Labours of Hercules – so far only Hercules and Antaeus has been recreated (in 2016), and a statue of a gladiator in 2017.[119][120][121]

In 2018 a replacement of the statue of Thalia holding a scroll with the words Pastorum Carmina Canto on it was erected near the Fane of Pastoral Poetry; the statue is based on a work by John Nost.[122] In 2019 a copy of the Grecian Urn sold in 1921 and now at Trent Park in north London has been erected near the Circle of the Dancing Faun.[123]

Gallery of features in the Grecian valley

The Temple of Concord and Victory

The Temple of Concord and Victory Interior, Temple of Concord and Victory

Interior, Temple of Concord and Victory The Fane of Pastoral Poetry

The Fane of Pastoral Poetry Sleeping Shepherd, in the Circle of the Dancing Faun

Sleeping Shepherd, in the Circle of the Dancing Faun.jpg.webp) The Cobham Monument

The Cobham Monument Samson and the Philistine

Samson and the Philistine

Western gardens

To the immediate west of the South Vista are the Western Gardens, which include the Eleven-Acre Lake.[51] This area of the gardens was developed from 1712 to 1770s when it underwent its final landscaping. The Eleven-acre lake was extended and given a natural shape in 1762.[124] In the woods to the north-west in 2017 the National Trust recreated the lost sculpture of the Wrestlers.[125] In 2018 the paths surrounding the sculpture were recreated and the Labyrinth around them replanted with 3,500 shrubs including magnolia, laurel, box, yew, spindle and hazel. Within the labyrinth are an outdoor skittle alley and a rustic swing.[126]

Also in this area in the woods to the north of the lake but on the east side is the Sleeping Wood designed by Bridgeman, at the heart of which use to stand the Sleeping Parlour being built in 1725 to a design by Vanbrugh, this was inspired by Charles Perrault's tale of Sleeping Beauty.[127]

Pegg's Terrace is a raised avenue of trees that follows the line of the south ha-ha between the Lake Pavilions and the Temple of Venus. Warden Hill Walk, also a raised avenue of trees, is on the western edge of the gardens, the southern part of which serves as a dam for the Eleven Acre Lake, links The Temple of Venus to the Boycott Pavilions.[128]

The buildings in this area are:

The Rotondo

Designed by Vanbrugh and built 1720–1721, this is a circular temple, consisting of ten unfluted Roman Ionic columns raised up on a podium of three steps. The dome was altered by Borra in 1773–1774 to give it a lower profile. In the centre is a statue of Venus raised on a tall decorated plinth, which is replacement for the original and is gilt.[129] The building was modelled on the temple of Venus at Knidos.[130]

Statue of Queen Caroline

This takes the form of a Tetrapylon, a high square plinth surmounted by four fluted Roman Ionic columns supporting an entablature which in turn supports the statue of Queen Caroline. On its pedestal is inscribed Honori, Laudi, Virtuti Divae Carolinae (To honour, Praise and Virtue of the Divine Caroline). According to the authors of National Trust's 1997 guidebook, it was probably designed by Vanbrugh.[131] It stands on the mound left by a former ice house.[132]

The Temple of Venus

Dated 1731 this was the first building in the gardens designed by William Kent. Located in the south-west corner of the gardens on the far side of the Eleven-Acre Lake. The stone building takes the form of one of Palladio's villas, the central rectangular room linked by two quadrant arcades to pavilions.[133] According to Michael Bevington, it was an early example of architecture being inspired by that of Roman baths.[134]

The main pedimented facade has an exedra screened by two full and two half Roman Ionic columns, there are two niches containing busts either side of the door of Cleopatra & Faustina, the exedra is flanked by two niches containing busts of Nero and Vespasian all people known for their sexual appetites. The end pavilions have domes. Above the door is carved VENERI HORTENSI "to Venus of the garden".[134]

The interior according to the 1756 Seeley Guidebook was decorated with murals painted by Francesco Sleter the centre of the ceiling had a painting of a naked Venus and the smaller Compartments were painted with a "variety of intrigues". The walls had paintings with scenes from Spenser's The Faerie Queene.[134] The paintings were destroyed in the late 18th century.[135]

The ceiling frieze had this inscription from the Pervigilium Veneris:

Nunc amet qui nondum amavit: |

Let him love now, who never lov'd before: |

The Hermitage

Designed c.1731 by Kent, heavily rusticated and with a pediment containing a carving of panpipes within a wreath, and a small tower to the right of the entrance.[136] It never housed a hermit.[134]

Dido's Cave

Little more than an alcove, probably built in the 1720s, originally decorated with a painting of Dido and Aeneas.[137] In c.1781 the dressed stone facade was replaced with tufa by the Marchioness of Buckingham.[138] Her son the 1st Duke of Buckingham turned it into her memorial by adding the inscription Mater Amata, Vale! (Farewell beloved Mother).[138] The designer is unknown.[137]

The Boycott Pavilions

Built of stone and designed by James Gibbs, the eastern one was built in 1728 and the western in 1729. They are named after the nearby vanished hamlet of Boycott. Located on the brow of a hill overlooking the river Dad, they flank the Oxford drive. Originally both were in the form of square planned open belvederes with stone pyramidal roofs. In 1758 the architect Giovanni Battista Borra altered them, replacing them with the lead domes, with a round dormer window in each face and an open roof lantern in the centre. The eastern pavilion was converted into a three-storey house in 1952.[139]

Gallery of features in the Western Gardens

The Rotondo viewed across Eleven Acre Lake

The Rotondo viewed across Eleven Acre Lake Statue of Queen Caroline

Statue of Queen Caroline.jpg.webp) Temple of Venus

Temple of Venus.jpg.webp) The Hermitage

The Hermitage Dido's Cave

Dido's Cave Eastern Boycott Pavilion

Eastern Boycott Pavilion

The Lamport Gardens

_-_Buckinghamshire%252C_England_-_DSC06720.jpg.webp)

Lying to the east of the Eastern Gardens, this was the last and smallest area just 17 acres (6.9 ha) added to the gardens. Named after the vanished hamlet of Lamport, the gardens were created from 1826 by Richard Temple-Grenville, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos and his gardener James Brown. From 1840, 2nd Duke of Buckingham's gardener, Mr Ferguson, and the architect Edward Blore, adapted it as an ornamental rock and water garden. Originally the garden was stocked with exotic birds including emus.[140]

The buildings in this area are:

The Chinese House

The Chinese House is known to date from 1738 making it the first known building in England built in the Chinese style.[141] It is made of wood and painted on canvas inside and out by Francesco Sleter. Originally it was on stilts in a pond near the Elysian Fields. In 1751 it was moved from Stowe and reconstructed first at Wotton House, the nearby seat of the Grenville family. In 1951 it then moved to Harristown, Kildare.[78] Its construction set a new fashion in landscape gardening for Chinese-inspired structures.[142][143]

It was purchased by the National Trust in 1996 and returned and placed in its present position. The Chinoiserie Garden Pavilion at Hamilton Gardens in New Zealand is based on Stowe's Chinese House.[144]

The Chinese House

The Chinese House.jpg.webp) Chinese House decoration

Chinese House decoration

Parkland

Surrounding the gardens, the park originally covered over 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) and stretched north into the adjoining county of Northamptonshire. In what used to be the extreme north-east corner of the park, about 2.5 mi (4.0 km) from the house over the county border lies Silverstone Circuit.[145] This corner of the park used to be heavily wooded, known as Stowe Woods, with a series of avenues cut through the trees, over a mile of one of these avenues (or riding) still survives terminated in the north by the racing circuit and aligned to the south on the Wolfe Obelisk though there is a gap of over half-mile between the two. It is here that one can find the remains of the gardener's treehouse, an innovative design comprising wood and textiles.[146]

There is a cascade of 25 ft (7.6 m) high leading out of the Eleven Acre Lake by a tunnel under the Warden Hill Walk on the western edge of the garden, into the Copper Bottom Lake that was created in the 1830s just to the south-west of the gardens. The lake was originally lined with copper to waterproof the porous chalk into which the lake was dug.[132]

The house's kitchen garden, extensively rebuilt by the 2nd Duke, was located at Dadford about 2/3 of mile north of the house. Only a few remains of the three walled gardens now exist, but originally they were divided into four and centred around fountains. There is evidence of the heating system: cast iron pipes used to heat greenhouses, which protected the fruit and vegetables, including then-exotic fruits.[147]

Stowe School had given the National Trust a protective covenant over the gardens in 1967, but the first part they actually acquired was the 28 acres (11 ha) of the Oxford Avenue in 1985, purchased from the great-great-grandson of the 3rd Duke, Robert Richard Grenville Close-Smith, a local landowner. The National Trust has pursued a policy of acquiring more of the original estate, only a fraction of which was owned by the school, in 1989 the school donated 560 acres (230 ha) including the gardens. In 1992 some 58 acres (23 ha) of Stowe Castle Farm to the east of the gardens was purchased, and in 1994 part of New Inn Farm to the south of the gardens was bought. Then 320 acres (130 ha) of Home Farm to the north and most of the 360-acre (150 ha) fallow deer-park to the south-west of the gardens were acquired in 1995, this was restored in 2003 there are now around 500 deer in the park.[148]

In 2005 a further 9.5 acres (3.8 ha) of New Inn Farm including the Inn itself were acquired. The trust now owns 750 acres (300 ha) of the original park. In the mid-1990s the National Trust replanted the double avenue of trees that surrounded the ha-ha to the south and south-west including the two bastions that project into the park on which sit the temples of Friendship at the south-east corner and Venus at the south-west corner, connecting with Oxford Avenue by the Boycott Pavilions, the Oxford Avenue then continues to the north-east following the ha-ha and ends level with the Fane of Pastoral Poetry at the north-east corner of the gardens.[148]

The buildings in the park include:

The Lamport Lodge

This, uniquely for the gardens, red brick lodge, in a Tudor Gothic style, with two bay windows either side of porch and is a remodelling of 1840–1841 by Blore of an earlier building. It acts as an entrance through the ha-ha. There are three sets of iron gates, that consists of one carriage and two flanking pedestrian entrances. They lead to an avenue of Beech trees planted in 1941 that lead to the Gothic Temple.[149]

Oxford Avenue

The Grand Avenue by the Corinthian Arch turns to the west to join the Queen's Drive that connects to the Oxford Avenue just below the Boycott Pavilions. The Oxford Avenue was planted in the 1790s, and sold to the National Trust in 1985 by the great-great-grandson of the 3rd Duke, Robert Richard Grenville Close-Smith (1936–1992), a local landowner. Close-Smith was the grandson of the Honourable Mrs. Caroline Mary Close-Smith, who was the 11th Lady Kinloss's daughter. This was one of the first acquisitions of the trust at Stowe.[150]

Water Stratford Lodge

Water Stratford Lodge is located over a mile from the house near the border with Oxfordshire, at the very start of the Oxford Avenue, by the village of the same name. Built in 1843, the single storey lodge is in Italianate style with a porch flanked by two windows, the dressings are of stone, with rendered walls. The architect was Edward Blore.[151]

The Oxford Gates

The central piers were designed by William Kent in 1731, for a position to the north-east between the two Boycott Pavilions,[152] they were moved to their present location in 1761, and iron railings added either side. Pavilions at either end were added in the 1780s to the design of the architect Vincenzo Valdrè. The piers have coats of arms in Coade stone manufactured by Eleanor Coade.[153]

The Oxford Bridge

The bridge was built in 1761 to cross the river Dad after this had been dammed to form what was renamed the Oxford Water; it was probably designed by Earl Temple. It is built of stone and is of hump-backed form, with three arches, the central one being slightly wider and higher than the flanking ones. With a solid parapet, there are eight decorative urns placed at the ends of the parapets and above the two piers.[153]

Features close to Oxford Avenue

The Oxford Avenue, looking south-west toward Water Stratford

The Oxford Avenue, looking south-west toward Water Stratford Water Stratford Lodge

Water Stratford Lodge.jpg.webp) Oxford Gates

Oxford Gates The Oxford Bridge & the Western Boycott Pavilion

The Oxford Bridge & the Western Boycott Pavilion

Wider estate buildings

Buildings on the wider estate, both on current and former land-holdings, include:

- Stowe Castle (Not owned by the National Trust) is two miles (3 km) to the east of the gardens, built in the 1730s probably to designs by Gibbs. The tall curtain wall visible from the gardens actually disguises several farmworkers' cottages.[154]

- The Bourbon Tower, approximately one thousand feet to the east of the Lamport Garden, was built c1741 probably to designs by Gibbs, it is a circular tower of three floors with a conical roof, it was given its present name in 1808 to commemorate a visit by the exiled French royal family.[155]

- The 2nd Duke's Obelisk near the Bourbon Tower, this granite obelisk was erected in 1864.[155]

- The Wolfe Obelisk stone 100 ft (30 m) high located about 2,000 ft (610 m) to the north-west of the garden, originally designed by Vanbrugh, it was moved in 1754 from the centre of the Octagon Lake and is a memorial to General Wolfe.[155]

- The Gothic Umbrello, also called the Conduit House, it houses beneath its floor a conduit. about a 1,000 ft (300 m) south of the Wolfe Obelisk, is a small octagonal pavilion dating from the 1790s. The coat of arms of the Marquess of Buckingham, dated 1793, made from Coade stone are place over the entrance door.[156]

- Silverstone Lodges (Not owned by the National Trust), built by the 1st Duke, these twin lodges used to flank the northern entrance to the park, and used to lead to the private carriage drive from Silverstone to the house. The drive no longer exists, this having long since been destroyed, part of it passed through what is now the racing circuit.[154]

North front

The North Front of Stowe School is closed to visitors. In front of the north facade of the house, the forecourt has in its centre an:

Equestrian statue of George I

This is a greater than life size equestrian statue of King George I by Andries Carpentière, located in the middle of the Forecourt, made of cast lead in 1723. It is on a tall stone plinth. It was this monarch that gave Lord Cobham his title of viscount in 1718 and restored his military command, leading to his involvement in the Capture of Vigo.[157]

The Menagerie

Hidden in the woods to the west of the South Vista. It was built by the Marquess of Buckingham for his wife as a retreat.[158] It was built in stone, c.1781, probably to the designs of Valdrè.[159] The 1st Duke converted it to a museum where he displayed his collections, which included a 32 ft (9.8 m) long Boa constrictor - at the time the largest in England.[158] The building is in private use by Stowe School.[160]

Demolished buildings and monuments

As the design of the gardens evolved many changes were made. This resulted in the demolition of many monuments. The following is a list by area of such monuments.

- The Approaches

- The Chackmore Fountain built c.1831, situated halfway down the Grand Avenue near the hamlet of Chackmore, dismantled in the 1950s.[161] It was photographed by John Piper.[162]

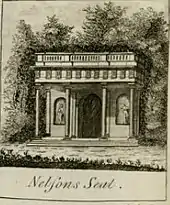

- The forecourt

- Nelson's Seat, a few yards to the north-west of the house, built in 1719–1720 to the design of Vanbrugh. It was named after William Nelson the foreman in-charge of building it, remodelled in 1773 with a Doric portico and demolished before 1797 the site is marked by a grass mound.[163]

- The western garden

- The Queen's Theatre created in 1721, stretching from the Rotondo to the south vista this consisted of a formal canal basin and elaborate grass terracing, this was re-landscaped in 1762–1764 to match the naturalistic form of the gardens as a whole.[164]

- The Vanbrugh Pyramid was situated in the north-western corner of the garden. Erected in 1726 to Vanbrugh's design, it was 60 ft (18 m) in height of steeply stepped form. It was demolished in 1797 and only the foundations survive.[165] The pyramid carried this inscription by Gilbert West:

Lamented Vanbrugh! This thy last Design,

Among the various Structures, that around,

Form'd by thy Hand, adorn this happy Ground,

This, sacred to thy Memory shall stand:

Cobham, and grateful Friendship so command.

- St. Augustine's Cave A rustic edifice with a thatched roof, built in the 1740s it had disappeared by 1797.[166]

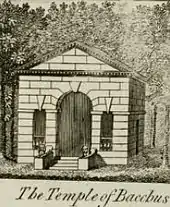

- The Temple of Bacchus designed by Vanbrugh and built c.1718, to the west of the house, originally of brick it was later covered in stucco and further embellished with two lead sphinxes. It was demolished in 1926 to make way for the large school chapel designed by Sir Robert Lorimer.[60]

- Coucher's Obelisk a dwarf obelisk erected before 1725, which was subsequently moved at least twice to other locations in the garden until its removal c.1763. It commemorated Reverend Robert Coucher, chaplain to Lord Cobham's dragoons.[163]

- Cowper's Urn A large stone urn surrounded by a wooden seat, erected in 1827 just to the west of the Hermitage, sold in 1921 its current location is unknown.[167]

- The Queen of Hanover's Seat in a clearing south-west of the site of the temple of Bacchus. Originally called the Saxon altar, it was the focus of the circle of Saxon Deities in 1727, it was moved in 1744 to the Grecian Valley to serve as a base of a statue of a 'Dancing Faun' until being moved to this location in 1843 and inscribed to commemorate a visit by the Queen of Hanover in that year. Sold in 1921 it is now in a garden in Yorkshire.[168]

- The Sleeping Parlour, probably designed by Vanbrugh, erected in 1725 in the woods next to the South Vista, it was square with Ionic porticoes on two sides one inscribed Omnia sint in incerto, fave tibi (Since all things are uncertain, indulge thyself). It was demolished in 1760.[169]

- The Cold Bath built around 1723 to Vanbrugh's design, it was a simple brick structure located near the Cascade. Demolished by 1761.[165]

- The Elysian fields

- The Temple of Modern Virtue to the south of the Temple of Ancient Virtue, built in 1737, it was built as an ironic classical ruin, with a headless statue in contemporary dress. It appears that it was left to fall down, there are slight remnants in the undergrowth.[166]

- The Gosfield Altar erected on an island in the lake, this was an Antique classical altar erected by Louis XVIII of France in gratitude for being allowed to use Gosfield Hall in Essex. It was moved from there by the 1st Duke in 1825, it had disappeared by 1843.[170]

- The Temple of Contemplation, now replaced by the Four Seasons Fountain. It was in existence by 1750 and had a simple arcaded front with pediment. It was later used as a cold bath until replaced by the fountain.[166]

- The Witch House built by 1738 it was in a clearing behind the Temple of Ancient Virtue, built of brick with sloping walls and a heavy, over-sailing roof, the interior had a mural painting of a witch. The date it was demolished is unknown.[166]

- The 1st Duchess's Urn near the Gothic Cross; it was of white marble, erected by the 2nd Duke to commemorate his mother.[168]

- The Eastern Garden

- The Imperial Closet this small building was situated to the east of the Temple of Friendship designed by Gibbs and built in 1739. The interior had paintings of Titus, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius with these inscriptions beneath each painting: Diem perdidi ("I have lost the day"); Pro me: si merear in me ("For me, but if I deserve it, against me"); and Ita regnes imperator, ut privatus regi te velis ("So govern when an emperor, as, if a private person, you would desire to be governed"). The building was demolished in 1759.[171]

- The 1st Duke's Urn erected in 1841 by the 2nd Duke to commemorate his father. It stood by the path to the Lamport Gardens. It was removed in 1931 to the school.[168]

- The Grecian Valley

- Sculpture: the valley used to have several lead sculptures placed at strategic points around it, including 'Hercules and Antaeus', 'Cain and Abel', 'Hercules and the Boar', 'The Athlete' and 'The Dancing Faun'.[172]

Several of the sculptures are located at Trent Park, purchased by Philip Sassoon in 1921. They include:

'Time and Opportunity', or 'Peace Embracing Time'

'Time and Opportunity', or 'Peace Embracing Time' A Sphinx

A Sphinx Samson defeating a Philistine

Samson defeating a Philistine Hercules and Antaeus

Hercules and Antaeus

Early tourism

The New Inn public house was constructed in 1717, and provided lodging and food for visitors who had come to admire the gardens and the park, with its neo-classical sculptures and buildings.[173] During the eighteenth century, visitors arrived at the Bell Gate.[2]

Stowe was the subject of some of the earliest tourist guide books published in Britain, written to guide visitors around the site.[2] The first was published in 1744 by Benton Seeley, founder of Seeley, Service, who produced A Description of the Gardens of Lord Cobham at Stow Buckinghamshire.[174][175] The final edition of this series was published in 1838.[2]

In 1748 William Gilpin produced Views of the Temples and other Ornamental Buildings in the Gardens at Stow, followed in 1749 by A Dialogue upon the Gardens at Stow.[176][177] In Gilpin's Dialogue two mythical figures, Callophilus and Polypthon, prefer different styles of gardening at Stowe to each other: Callophilus prefers formality; Polypthon, the romantic and ruinous.[178]

Copies of all three books were published in 1750 by George Bickham as The Beauties of Stow.[179]

To cater to the large number of visitors from France, an anonymous French guidebook, Les Charmes de Stow, was published in 1748.[180] In the 1750s Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote about the gardens, which spread their notoriety throughout Europe.[181] He had this to say:

Stowe is composed of very beautiful and very picturesque spots chosen to represent different kinds of scenery, all of which seem natural except when considered as a whole, as in the Chinese gardens of which I was telling you. The master and creator of this superb domain has also erected ruins, temples and ancient buildings, like the scenes, exhibit a magnificence which is more than human.

— Jean Jacques Rousseau

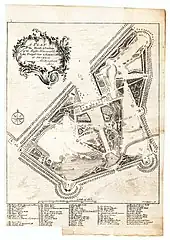

Another francophone guide was published by Georges-Louis Le Rouge in 1777. Détails de nouveaux jardins à la mode included engravings of buildings at Stowe as well as at other famous gardens in Britain.[182][183] In Germany, Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld published Theorie der Gartenkunst in 5 volumes in Leipzig 1779–1785, which included Stowe.[184][185]

Cultural significance

The World Monuments Fund describes Stowe as "one of the most beautiful and complex historic landscapes in Britain".[186] The range and stature of the designers deployed, including Bridgeman, Brown, Vanbrugh, Gibbs and Kent;[187] the intricacy of the architectural and allegorical schemes those designers devised; the unified conception they created; the extent of its survival;[188] and its influence as the "birthplace of the English art of landscape gardening",[188] combine to make Stowe "a garden of international repute".[189] Its importance is recognised in the large number of listed structures within the garden and the wider park, and its own Grade I listing designation.[190]

Architecture and horticulture

The Temples’ wealth and prestige enabled them to engage most of the leading designers of the Georgian period. The outline of the present gardens was laid by Charles Bridgeman, and some of the earliest of the forty monuments and temples situated on the estate were designed by John Vanbrugh.[191] They were followed by William Kent, James Gibbs and then by a youthful Capability Brown, who was appointed head gardener at Stowe at the age of 25, and later married in the estate church.[192] Tim Knox, in his chapter "The Fame of Stowe", published in the Trust's book, Stowe Landscape Gardens, suggests that Brown's subsequent career, which saw him deploy the expertise gained at Stowe across a large number of other landscape parks throughout England, may in fact be the garden's most significant legacy.[193] In addition to the major British architects deployed, the Temples engaged a number of prominent Europeans. Although they worked primarily on the house, they also contributed to some of the garden structures. Giovanni Battista Borra worked on the Temple of Concord and Victory and modernised the Boycott Pavilions and the Oxford Gate.[194] Georges-François Blondel may have undertaken work on the Queen's Temple,[195] while Vincenzo Valdrè designed the Oxford Gate lodges, the base of the Cobham Monument and may have been responsible for the Menagerie.[196]

The work of so many major architects, some of whom came to make improvements and alterations to the house but also contributed to the design and structure of the garden and park, gives the gardens and park at Stowe a particular architectural flavour.[197] It is less a garden of plants and flowers, and more a landscape of lawns, water and trees, with carefully contrived vistas and views which frequently culminate in eye-catcher structures.[198][199] Other gardens of the period, such as Claremont, Kew and Stourhead followed this style, but few matched the scale of Stowe. While the buildings in the grounds at Stowe are natural foci for attention, the landscaping around the structures is as vital to the overall scheme.[200] The gardens progressed from a formal, structured layout, through increasing naturalisation.[201] The planting of grasses and trees was equally deliberate, designed to lead the eyes of the visitor on to the next area, and to bring a sense of drama to the landscape.[202]

The gardens incorporate a number of architectural and horticultural "firsts". They are themselves considered the earliest example of the English landscape garden.[188][203] Defining the borders of the park he began, Charles Bridgeman designed the first ha-ha in England, a feature that was widely imitated.[204] Within the garden, Kent's Chinese House was perhaps England's earliest Chinoiserie building.[141] So notable were the gardens at Stowe that they were emulated across the world. Thomas Jefferson visited, and bought the guidebooks, transporting ideas across the Atlantic for his Monticello estate.[205] Eastwards, it inspired gardens in Germany such as that at Wörlitz,[206] and those created at Peterhof and Tsarskoye Selo by Catherine the Great.[207][lower-alpha 4]

Sermon in stone – the "meaning" of the garden

A central element of the uniqueness of Stowe were the efforts of its owners to tell a story within, and through, the landscape. A symposium organised by the Courtauld Institute, The Garden at War: Deception, Craft and Reason, suggests that it was not "a garden of flowers or shrubs [but] of ideas."[209] The original concept may have been derived from an essay written by Joseph Addison for the Tatler magazine.[210] The landscape was to be a "sermon in stone",[211] emphasising the perceived Whig triumphs of Reason, the Enlightenment, liberty and the Glorious Revolution, and 'British' virtues of Protestantism, empire, and curbs on absolutist monarchical power. These were to stand in contrast with the debased values of the corrupt political regime then prevailing.[212] The temples of Ancient Virtues and British Worthies were material expressions of what the Temples themselves supported, while the intentionally ruined Temple of Modern Virtue was a contemptuous depiction of what they opposed, the buildings and their setting making a clear moral and political statement.[213] Praising the "grandeur of [its] overall conception", John Julius Norwich considered that the garden at Stowe better expressed the beliefs and values of its creators, the Whig Aristocracy, "than any other house in England."[214]

As Stowe evolved from an English baroque garden into a pioneering landscape park, the gardens became an attraction for many of the nobility, including political leaders.[215] Many of the temples and monuments in the garden celebrate the political ideas of the Whig party.[216][217] They also include quotes by many of the writers who are part of Augustan literature, also philosophers and ideas belonging to the Age of Enlightenment.[218] The Temple family used the construction of the Temple of Ancient Virtue, modelled on the Temple of Sibyl in Tivoli, to assert their place as a family of 'ancient virtue'.[215][201] Figures depicted in the temple include Homer, Socrates, Epaminondas and Lycurgus, whose attributes are described with Latin inscriptions that promote them as "defenders of liberty".[216]

Richard Temple was also the leader of a political faction known as Cobham's Cubs, established as opposition to the policies of Robert Walpole.[219] Part of the gardens at Stowe were altered to illustrate this rivalry: Temple erected the Temple of Modern Virtue, purposefully constructed as a ruin and located next to a decaying statue of Walpole.[219] (The Temple of Modern Virtue is no longer extant.[220])

The principles of the English landscape garden were unpopular with Tory supporters who, according to the historian Christopher Christie, did not approve of how they "displayed in a very conspicuous way" the estate and parkland. There was also concern, from commentators such as Oliver Goldsmith, that demolishing the homes of tenants was "unacceptable and an abuse of power".[201]

Contemporary satire reflected the role the gardens played in political life by portraying caricatures of the better-known politicians of history taking their ease in similar settings.[206] In 1762, Lord Kames, a philosopher, commented that for the visitor the political commentary within the garden at Stowe may be "something they guess" rather than clearly explained.[221]

Art

Charles Bridgeman commissioned 15 engravings of the gardens from Jacques Rigaud (fr), which were published in 1739.[222] The etching was undertaken by another French artist, Bernard Baron. They show views of the gardens with an array of fashionable figures, including the Italian castrato Senesino, disporting themselves in the foreground. One set is held in the Royal Collection.[223] In 1805-9 John Claude Nattes painted 105 wash drawings of both the house and gardens.[224] Stowe is one of the houses and gardens depicted on the frog service, a dinner service for fifty people commissioned from Wedgwood by Catherine the Great for her palace at Tsarskoye Selo.[225] John Piper produced watercolours of some of the monuments in the gardens, including the Temple of British Worthies, amongst others.[226]

The gardens at Stowe were as much influenced by art as they provided an inspiration for it. The idealised pastoral landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, with their echoes of an earlier Arcadia, led English aristocrats with the necessary means to attempt to recreate the Roman Campagna on their English estates.[227] Kent's acquaintance, Joseph Spence, considered that his Elysian Fields were "a picture translated into a garden".[228]

Poetry

Alexander Pope who first stayed at the house in 1724, celebrated the design of Stowe as part of a tribute to Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington.[229] The full title of the 1st edition (1731) was An Epistle to the Right Honourable Richard Earl of Burlington, Occasion'd by his Publishing Palladio's Designs of the Baths, Arches, Theatres, &c. of Ancient Rome.[230] Lines 65–70 of the poem run:

Still follow Sense, of ev'ry Art the Soul,

Parts answ'ring parts shall slide into a whole,

Spontaneous beauties all around advance,

Start ev'n from Difficulty, strike from Chance;

Nature shall join you, Time shall make it grow

A Work to wonder at—perhaps a STOWE.— Alexander Pope, An Epistle to the Right Honourable Richard Earl of Burlington, Occasion'd by his Publishing Palladio's Designs of the Baths, Arches, Theatres, &c. of Ancient Rome

In 1730 James Thomson published his poem Autumn, part of his four works The Seasons.[231] Stowe is referenced in lines 1040–46:

Or is this gloom too much? Then lead, ye powers

That o'er the garden and the rural seat

Preside, which shining through the cheerful land

In countless numbers blest Britannia sees,

Oh lead me to the wide-extended walks,

The fair majestic paradise of Stowe!— James Thomson, Autumn

In 1732 Lord Cobham's nephew Gilbert West wrote a lengthy poem, The Gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Viscount Cobham, a guide to the gardens in verse form.[232] Another poem which included references to Stowe is The Enthusiast; or lover of nature by Joseph Warton.[220]

Historic importance

Stowe has a "more remarkable collection of garden buildings than any other park in [England]".[233] Some forty structures remain in the garden and wider park; Elizabeth Williamson considered that the number of extant structures made Stowe unique.[188] Of these, some 27 separate garden buildings are designated Grade I, Historic England's highest grade, denoting buildings of "exceptional interest".[234] The remainder are listed at Grade II* or Grade II. The garden and surrounding park are themselves listed at Grade I on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[235] In the opening chapter of Stowe House: Saving an Architectural Masterpiece, the most recent study of the house and the estate, Jeremy Musson describes the mansion as "the centrepiece of a landscape garden of international repute",[189] while the National Trust, the garden's custodian, suggests that the estate is "one of the most remarkable legacies of Georgian England".[236] The architectural historian Christopher Hussey declared the garden at Stowe to be the "outstanding monument to English Landscape Gardening".[237]

Notes

- Despite these criticisms, the authors of the Pevsner Guide acknowledged the school's contribution; "were it not for the school, there would be no Stowe: the demolition merchants were waiting when it intervened."[39]

- The statue of Apollo is yet to be installed.

- His death is marked with an epitaph, the first and last lines of which read:

To the memory of Signor Fido an Italian of good Extraction, who came to England not to bite us, like most of his countrymen, but to gain an honest livelihood. He hunted not after fame, yet acqui'd it: ...

Reader, this stone is guiltless of Flattery; for he to whom it is inscrib'd was not a Man but a Greyhound. - The profusion of buildings in the grounds did not meet with universal approval. Prince Pückler-Muskau, the aristocratic tourist who visited Stowe in 1818, remarked; "it is so overcrowded with temples of all kinds that the greatest improvement that could be carried out here would consist in pulling down about ten or twelve of them."[208]

References

- "History of Stowe". National Trust. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- Bevington 1994, p. 10.

- Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (4 October 2011). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 585. ISBN 978-0-470-90248-6. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- Robinson 1990, p. 20.

- Willis, Peter (1977). Charles Bridgeman and the English landscape garden. London: A. Zwemmer. p. 106. ISBN 0-302-02777-7. OCLC 4206348. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- Hart, Vaughan (2008). Sir John Vanbrugh: Storyteller in Stone. Yale University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-300-11929-9. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.