Ninlil

Ninlil (𒀭𒎏𒆤 DNIN.LÍL; meaning uncertain) was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of Enlil. She shared many of his functions, especially the responsibility for declaring destinies, and like him was regarded as a senior deity and head of the pantheon. She is also well attested as the mother of his children, such as the underworld god Nergal, the moon god Nanna or the warrior god Ninurta. She was chiefly worshiped in Nippur and nearby Tummal alongside Enlil, and multiple temples and shrines dedicated to her are attested from these cities. In the first millennium BCE she was also introduced to Ḫursaĝkalamma near Kish, where she was worshiped alongside the goddess Bizilla, who was likely her sukkal (attendant deity).

| Ninlil | |

|---|---|

Wife of Enlil | |

| Other names | Sud, Kutušar, Mullilu |

| Major cult center | |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nisaba and Ḫaya |

| Consort | Enlil |

| Children | |

| Equivalents | |

| Syrian equivalent | Shalash |

| Ugaritic equivalent | Athirat |

| Assyrian equivalent | Mullissu and possibly Šerua |

At an early date Ninlil was identified with the goddess Sud from Shuruppak, like her associated with Enlil, and eventually fully absorbed her. In the myth Enlil and Sud, Ninlil is the name Sud received after marrying Enlil. Nisaba, the goddess of writing, and her husband Haya are described as her parents. While Ninlil's mother bears a different name, Nunbaršegunu, in the myth Enlil and Ninlil, the god list An = Anum states that it was an alternate name of Nisaba. Syncretism with Sud also resulted in Ninlil acquiring some of her unique characteristics, such as an association with healing goddesses and with Sudaĝ, a name of the wife of the sun god Shamash. References to these connections can be found in various Mesopotamian texts, such as a hymn referring to Ninlil as a healing goddess or a myth apparently confusing her with Sudaĝ in the role of mother of Ishum.

In Syrian cities such as Mari, Emar and Ugarit, Ninlil was closely associated with the local goddess Shalash, the spouse of Dagan, a god regarded as analogous to Enlil. This equivalence is also attested in Hurrian religion, where Shalash was the spouse of Kumarbi, another god regarded as similar to Enlil. However, Ninlil is also attested as a deity in her own right in Hurrian texts, and could serve as a divine witness of treaties in this context.

In the Neo-Assyrian Empire Ninlil was reinterpreted as the spouse of the supreme Assyrian god Ashur, and in this role developed into Mullissu, who in turn could be identified with various deities from the pantheon of Assyria, such as Šerua or local forms of Ishtar from cities such as Nineveh.

Name

Through most of the third millennium BCE, Ninlil's name was written with the Sumerian cuneiform sign LÍL (KID[1]), while Enlil's with identically pronounced É.[2] From the Ur III period onward LÍL started to be used for both deities.[3] The causes of these phenomena remain unknown.[4] The pronunciation Ninlil is confirmed by a gloss writing the name syllabically as ni-in-lil.[5] The meaning of the second element of the name is not certain, though a late explanatory text translates the name Ninlil as GAŠAN za-qí-qí, "lady of the breeze," which matches a common theory according to which Enlil's name should be understood as "lord wind."[6]

A variant Akkadian form of the name was Mullilu, in neo-Assyrian sources spelled as Mullissu, in Aramaic texts as mlš, and in Mandaic as mwlyt.[5] This form of the name was also known to Greek authors such as Herodotus (who transcribes it as "Mylitta") and Ctesias.[5] It is possible that it originally developed as a feminine equivalent of Enlil's dialectical Emesal name Mullil (derived from Umum-lil, umun being the Emesal form of en).[5] The names Mullil and Mullissu could also be connected with the Akkadian word elēlu, and therefore it is possible they were understood as "he who makes clean" and "she who makes clean," respectively.[5]

According to the god list An = Anum, an alternate name of Ninlil was Sud,[7] written dSU.KUR.RU.[8] It originally referred to the tutelary deity of Shuruppak, who was syncretised with Ninlil.[8] Jeremiah Peterson proposes that the Sumerian writing of Sud's name was misunderstood as an Akkadian noun based on a single copy of the Nippur god list in which a deity named dsu-kur-ru-um occurs.[9] This view is not supported by Manfred Krebernik, who argues this entry has no relation to Sud and represents a deified cult emblem, specifically a lance (Akkadian: šukurrum).[10] The deified lance is elsewhere attested in association with the god Wer.[11]

Character

As the wife of Enlil, Ninlil was believed to be responsible for similar spheres of life, and stood on the top of the pantheon alongside him.[12] Like him, she was believed to be in charge of the determination of fates, and in a few inscriptions even takes precedence over him in this role.[13] A late hymn states that she was the ruler of both earth and heaven, and that Enlil made no decision without her.[12] Kings from the Third Dynasty of Ur considered both of them to be the source of earthly royal authority.[13] In literary texts, she could be described as responsible for appointing other deities to their positions alongside her husband. For example, a hymn credits the couple with bestowing Inanna's position upon her.[14] Another states that Nergal was entrusted with the underworld by them both.[15] In yet another composition, they are also credited with giving Ninisina "broad wisdom created by an august hand."[15] Nuska was also believed to owe his position to a decree of both Enlil and Ninlil.[16] It has been suggested that an entire standardized series of hymns describing how various deities were appointed to their positions this way existed.[17]

Due to Enlil's position as the father of gods, Ninlil could be analogously viewed as the mother of gods.[10] In a compilation of temple hymns (ETCSL 4.80.1. in the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature) she is one of the four goddesses described as ama, "mother," the other three being Nintur (a goddess of birth), Ninisina and Bau.[18] It is possible that Ninlil could also be referred to with the epithet tamkartum, a rare feminine form of the word tamkarum, "merchant."[19] Enlil could be described as a divine merchant (ddam-gar3), which according to Jeremiah Peterson might mean that dta-am-kart-tum attested in a fragment of a non-standard Old Babylonian god list from Nippur is a name of Ninlil referring to a similar role.[19]

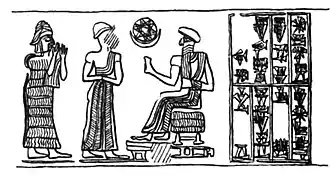

Like many other deities, she could be compared to a cow, though this does not indicate an association with cattle or theriomorphic character in art.[12] It is possible that she is depicted as a seated enthroned goddess on at least one cylinder seal from the Ur III period.[20] Another might depict her as a tall goddess wearing the horned headdress of divinity leading a supplicant, followed by a shorter goddess, possibly representing Nintinugga, whose devotee the owner of the seal was according to accompanying inscription.[21]

In Mesopotamian astronomy, Ninlil was associated with two constellations, the mulmar-gíd-da ("wagon") corresponding to Ursa Major and the mulÙZ ("goat"), corresponding to Lyra, as attested in the compendium MUL.APIN and other sources.[12]

It has been argued that through the history of ancient Mesopotamian religion, the domain of Ninlil continued to expand,[22] sometimes at the expense of other goddesses.[23]

Ninlil and Sud

It is agreed that Ninlil fully absorbed the goddess Sud,[24] like her viewed as the spouse of Enlil.[25] Her association with this god goes back to the Early Dynastic period.[8] A mythological explanation made Ninlil a name Sud received after getting married.[26] The syncretism between them is attested in the god list An = Anum,[7] but in the older Weidner god list Sud appears not with Enlil and Ninlil, but rather among the medicine goddesses, such as Gula.[10]

The process of conflation meant that some associations originally exclusive to Sud could be transferred to Ninlil as well.[27] For example, the Hymn to Gula composed by a certain Bulluṭsa-rabi attests that she could be viewed as a goddess of healing, which has been identified as a possible result of Sud's association with Gula.[22] Sud could also be associated with Sudaĝ, one of the names of the wife of sun god Shamash.[27]

Hurrian reception

Ninlil was also incorporated into Hurrian religion, where she and Enlil were regarded as two of the so-called "primeval gods,"[28] a group of deities belonging to the former divine generations who resided in the underworld.[29] Other senior Mesopotamian deities like Anu and Alalu could be listed among them too.[30] They could be invoked as divine witnesses of treaties.[30]

Assyrian reception

From the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I onward, Ninlil started to be viewed as the wife of the Assyrian head god, Ashur.[31] The equivalence between Ninlil understood as spouse of Enlil and Mullissu understood as spouse of Ashur is well attested in neo-Assyrian sources.[32]

It has been argued that Mullissu's newfound position might have resulted in conflation with Šerua, as in scholarship it is often assumed that this goddess was the original wife of Ashur.[31] It has also been proposed that while originally regarded as his wife, she later came to be replaced (rather than absorbed) by Mullissu, and was demoted to the position of a daughter or sister.[33] A different theory, based on Aramaic inscriptions from the Parthian period, makes Šerua's initial position that of a daughter of Ashur, who later came to be viewed as his second wife alongside Mullissu.[33] Mullissu also came to be conflated with Ishtar of Nineveh, who was also recast as Ashur's consort in the neo-Assyrian period.[34] It has been argued that especially in texts from the reign of Ashurbanipal, the names are synonymous.[34] Similar process is also attested for Ishtar of Arbela and Ishtar of Assur.[34] At the same time Ishtar without any epithets indicating association with a specific location could appear in Assyrian texts separately from the goddesses of Nineveh and Arbela identified with Mullissu, indicating that they coexisted as separate members of the pantheon.[35]

Associations with other deities

Family

Ninlil's husband was Enlil.[8] As early as in the Early Dynastic Period, they are attested as a couple in sources from Abu Salabikh and Ur.[36] The relationship between them is further affirmed by most of the later major god lists: the Weidner list, the Nippur god list, the Isin god list, the Mari god list, Old Babylonian An = Anum forerunner and An = Anum itself.[8] As Nilil's husband, Enlil could be called "the allure of her heart" (Sumarian: ḫi-li šag4-ga-na).[37] It has been pointed out that in some cases, they functioned as unity in religious texts.[38] A certain Enlilalša, a governor of Nippur, acted as a priest of both Enlil and Ninlil, though the terms used to refer to these functions are not identical (nu-eš3 and gudu4, respectively).[39]

The myth Enlil and Sud indicates that Ninlil was regarded as the daughter of Nisaba, the goddess of writing, and her husband Haya.[31] In Enlil and Ninlil her mother is instead a goddess named Nunbaršegunu, who according to the god list An = Anum was identified with Nisaba.[31] Eresh, the cult center of Nisaba, could be called the "beloved city of Ninlil," as attested in the composition Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana.[40] It is not known if she actually had a temple there.[41]

As the wife of Enlil, Ninlil could be regarded as the mother of Ninurta, as attested for example in Ninurta's Return to Nippur (Angim), though other goddesses, such as Nintur, Ninhursag or Dingirmah are attested in this role too.[42] She was practically without exception regarded as the mother of Nergal.[43] As the mother of those two gods, she could be referred to as Kutušar.[44] This epithet is attested in association with Tummal.[44] It also occurs in an inscription of Shamshi-Adad V, in which Kutušar is called "the lady equal to Anu and Dagan" (Akkadian: bēlti šinnat Anum u Dagan), with Dagan most likely serving as a name of Enlil due to the long-standing association between those two gods.[45] Ninlil was also the mother of the moon god Nanna.[46] By extension, Inanna (Ishtar) and Utu (Shamash) could be viewed as her grandchildren.[47]

While a number of sources attest that Ninlil could be regarded as the mother of Ninazu, according to Frans Wiggermann this tradition might only be a result of the growing influence of Nergal on this god's character, which was also responsible for his role as a divine warrior.[48] He points out that in other sources Ninazu was the son of Ereshkigal and a nameless male deity, presumably to be identified with Gugalanna, which reflected his own character as a god of the underworld.[48] Ninazu is nonetheless one of the children born in the myth Enlil and Ninlil, where his brothers are Nanna, Meslamtaea (Nergal) and Enbilulu.[48] The last of these deities was responsible for irrigation, and in another tradition was a son of Ea, rather than Enlil and Ninlil.[49]

Ninlil could also be identified with Nintur, who was regarded as the mother of another of Enlil's sons, Pabilsag.[50] In a hymn, she is credited with bestowing various titles and abilities on Ninisina,[51] who is well attested as Pabilsag's wife.[52]

Court

Ninlil's sukkal (attendant deity) was most likely the goddess Bizilla.[53][54] In a star list, Bizilla corresponds to the "star of abundance," mulḫé-gál-a-a, which in turn is labeled as the sukkal of Ninlil in the astronomical compendium MUL.APIN.[53] In most other contexts, Bizilla was closely associated with the love goddess Nanaya.[55] An explanatory temple list known from Neo-Babylonian Sippar,[56] arranged according to a geographic principle, states that a temple of Bizilla existed in Ḫursaĝkalama, a cult center of Ninlil.[57]

Ninĝidru (written dNIN.PA; a second possible reading is Ninĝešduru[58]) fulfills the role of a sukkal in a hymn to Sud, where she is described as responsible for receiving visitors in her mistress' temple.[59] She is also mentioned alongside Sud in a fragment of an inscription of an unidentified ruler (ensi) of Shuruppak from the Sargonic period.[58] Christopher Metcalf assumes that Ningidru should be considered a male deity,[58] but other authors consider her to be a goddess.[60][59] Her name indicates she was a divine representation of the sceptre, and she was associated with Ninmena.[59]

Another courtier of Ninlil was her throne bearer Nanibgal,[61] whose name was initially synonymous with Nisaba but came to refer to a distinct deity later.[62] Her other servants, known from the god list An = Anum, were an udug (in this context the term denotes a protective spirit) of her temple Kiur named Lu-Ninlilla and a counselor named Guduga.[61]

A hymn to Sud from the reign of Bur-Suen of Isin refers to Asalluhi as her doorkeeper.[59] Christopher Metcalf, who translated this composition, does not consider this to be an indication that he was closely associated with her otherwise, as the connection is not present in any other known texts,[58] but Jeremiah Peterson in a review of Metcalf's publication notes that it is not impossible that it had a longer tradition.[63] He suggests that as the god of Kuara, Asalluhi might have been associated with Sud and Shuruppak due to both of those cities being viewed as predating the mythical great flood in Mesopotamian tradition.[64]

Ninlil and Shalash

The god list An = Anum attests that the Syrian goddess Shalash (not to be confused with the weather goddess Shala[65]) was viewed as analogous to Ninlil, similar to how their respective husbands, Dagan and Enlil, were viewed as equivalents.[66] It is possible that in Mari, Ninlil's name was a logographic representation of Shalash's.[67] She is also attested alongside Dagan in an offering list from Emar, though she most likely simply represents his local spouse,[68] presumably to be identified as Shalash.[69] She is otherwise absent from Emar, the only other exception being an imported Mesopotamian god list, a variant of the Weidner list.[70] Especially in Mari, Shalash could also be identified with Ninhursag instead.[71]

A trilingual list from Ugarit attests the equivalence between Mesopotamian Ninlil, Ugaritic Athirat and a Hurrian goddess only labeled as Ašte Kumurbineve,[72] which means "wife of Kumarbi" in the Hurrian language.[73] Kumarbi was a god considered analogous to Dagan[74] and due to this association Shalash also came to be viewed as his wife.[28] As a pair, they could also be equated with Enlil and Ninlil.[28]

Worship

Ninlil was chiefly worshiped in the cult centers of her husband Enlil.[61] Nippur was therefore also associated with her, as already attested in sources from the Early Dynastic Period.[41] One of the oldest texts mentioning the worship of Ninlil might be an inscription of a certain Ennail, possibly a ruler (lugal) of Kish, who states that he collected first fruit offerings for Enlil and Ninlil.[46] The text is only known from copies from the Ur III period, but a fragment of a statue from Nippur indicates that a ruler named Ennail reigned at some point before the Sargonic period.[75] In the Ekur temple complex, Ninlil was worshiped in the Kiur (Sumerian: "leveled place"),[76] which can be itself described as a "complex" in modern scholarly literature.[77] It appears in inscriptions of Ur-Ninurta of Isin and Burnaburiash I of the Kassite dynasty of Babylon.[76] The same name was also applied to a shrine of Ninlil which was a part of a temple of Ninimma in the same city.[76] Further locations within the Ekur temple complex dedicated to her include the Eitimaku, alternative known as Eunuzu ("house which knows no daylight"),[78] a shrine described as her bedchamber,[79] the Ekurigigal ("house, mountain endowed with sight") which was a storehouse dedicated jointly to her and Enlil, mentioned as early as during the reigns of Damiq-ilishu and Rim-Sîn I.[80] Multiple small shrines in Nippur were also dedicated to her, including the Ešutumkiagga ("house, beloved storeroom") built by Ur-Nammu,[81] the Emi-Tummal (translation of the first element uncertain),[82] a shrine called Abzu-Ninlil ("Apsu of Ninlil"), attested in documents from the Ur III period,[83] which according to Manfred Krebernik was a water basin,[41] and a further sanctuary distinct from those three whose name is not fully preserved, also known from documents from the Ur III period.[84]

A further cult center of Ninlil was Tummal, attested in sources from the Ur III period already.[85] It was located in the proximity of Nippur and Puzrish-Dagan, and might correspond to modern Tell Dalham, located 21 kilometers south of the former of those two ancient cities in modern Iraq.[85] Piotr Steinkeller proposes that it was initially a cult center of Ninhursag, and that she was replaced at some point with Ninlil, but this view is not supported by other researchers.[86] E-Tummal also functioned as an alternate name of Ninlil's main temple in Nippur.[87] In the Ur III period, during a festival taking place in Tummal she was believed to renew the king's legitimacy by decreeing his fate.[88] It has been suggested that it was also a celebration of her marriage to Enlil, and that various songs referring to sexual encounters between them might be related to it, though no direct evidence for the latter theory is currently available.[89]

It has been proposed that a further location associated with Ninlil was NUN.KID from the Archaic City List, a document from the Early Dynastic Period, but this is unlikely as the orthography of the name varies between sources, and there is no basis to assume it was read as Ninlil or associated with her in some way.[90]

It is possible that a temple of Ninlil attested in inscriptions of Rim-Sîn I, Eninbišetum ("house worthy of its lady") was located in Ur.[91] It should not be confused with a similarly named temple of Ninshubur, Eninbitum (also "house worthy of its lady"), mentioned by the same ruler and most likely located in the same city.[91]

Ninlil was also worshiped in Dur-Kurigalzu, and a temple dedicated to her, the Egašanantagal ("house of the lady on high") was built there by king Kurigalzu I of the Kassite dynasty of Babylon.[92]

In the first millennium BCE, according to Joan Goodnick Westenholz specifically during the reign of Marduk-apla-iddina II (721-710 BCE), Ninlil was also introduced to Ḫursaĝkalamma, a settlement within the sphere of influence of Kish, replacing the older deity worshiped there, Ishtar.[54] The details of this process are presently unknown, though it is possible the goddess of Ḫursaĝkalamma was at this point understood not as a manifestation of Ishtar but as an ištaru, a generic term referring to female deities, and therefore could be assigned the name Ninlil without any type of syncretism occurring.[54] Ninlil's temple there was known as E-Ḫursaĝkalamma ("house, mountain of the land").[93] A ziggurat possibly dedicated to her, Ekurmah ("house, exalted mountain"), also existed in the same location.[80] It has also been proposed that she was worshiped in the akitu temple of Zababa in Kish.[94] A festival held in Babylon in honor of Gula involved Ninlil, as well as Bizilla, both of whom acted as the divine representatives of Kish, alongside Belet Eanna (Inanna of Uruk), Belet Ninua ("Lady of Nineveh") and the deity dKAŠ.TIN.NAM, possibly to be identified as a late form of the beer goddess Ninkasi.[95]

One more temple of Ninlil, Emebišedua (house built for its me), which was also a temple of Enlil, is known from the Canonical Temple List, but its location is not known.[96]

Sud in Mesopotamian religion

Sud's main cult center was Shuruppak (modern Fara).[61] The name of the city was written the same as that of its tutelary goddess, though with a different determinative, SU.KUR.RUki rather than dSU.KUR.RU, similar to how the names of Enlil and Nisaba could be used to represent Nippur and Eresh, respectively.[61] Much information about the religious life of this city has been obtained from administrative texts, and it is known that in addition to Sud, deities such as Nisaba, Ninkasi, Ninmug and Ninshubur were also worshiped there.[97] Sud's importance in the local pantheon is reflected in the number of theophoric names invoking her.[61] At the same time there is relatively little evidence regarding her worship outside of Shuruppak, and she is absent from earliest sources from cities such as Lagash and Ur.[61] She is nonetheless also attested in sources from Abu Salabikh[61] and Adab.[98] In the latter of these two cities she is attested in theophoric names from the Early Dynastic period, such as Sud-anzu and Sud-dazi.[98] She does not appear in any offering lists from Adab predating the Sargonic period.[98]

It is commonly assumed that Sud ceased to be worshiped under own name with the decline of Shuruppak,[27] which is typically dated to the beginning of the second millennium BCE.[25] However, Christopher Metcalf points out that Sud was still actively worshiped by kings of the Isin dynasty, namely Bur-Suen and Enlil-bani.[99] It has also been noted that it cannot actually be established how long Shuruppak remained inhabited due to lack of archeological data, as erosion only left the oldest layers of the city to excavate.[100] At the same time, the fact that Shuruppak retained a degree of religious importance does not necessarily indicate that it was still an administrative center or a major urban settlement in the Isin-Larsa period.[101]

A recently published hymn mentioning Bur-Suen indicates that Sud was regarded as responsible for granting him the right to rule.[25] It has been proposed that the Isin dynasty's interest in Sud was based on her association with Gula, as medicine deities were particularly venerated in Isin, but there is no reference to her fulfilling such a role in this composition.[99] One of Bur-Suen's successors, Enlil-bani, rebuilt a temple dedicated to her, Edimgalanna (Sumerian: "house, great bond of heaven"; more literally "house, mooring pole of heaven").[102] It is generally agreed that it was located either in Shuruppak or close to it.[101] A further temple of Sud was Ekisiga ("house of funerary offerings"),[103] possibly also located in Shuruppak.[104] The name is homophonous with that of a temple of Dagan in Terqa, but the latter has a different meaning ("house, silent place").[103] Ekisiga and Edimgalanna appear side by side in a number of texts, for example in a lamentation describing the destruction of Shuruppak.[99] It is also possible that Esiguz ("house of goat hair") located in Guaba was a temple of Sud, but this is uncertain, and it is better attested in association with Inanna of Zabalam.[105] A further temple which seemingly was primarily dedicated to Sudaĝ but possibly could had been associated with Sud as well was Ešaba ("house of the heart"), whose location is presently unknown.[106]

In the Old Babylonian period, Shuruppak became a subject of antiquarian interest for Mesopotamian scholars.[101] It continued to be referenced in literature even after abandonment.[107] Utnapishtim, the protagonist of the flood myth which forms a part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, is described as a Shuruppakean,[107] while the text referred to as Nippurian Taboos 3 in modern scholarship alludes to the belief that a confrontation between the primordial deity Enmesharra and either Enlil or Ninurta took place there.[108] A late occurrence to Sud herself as an independent figure can be found in the Canonical Temple List,[109] which has been dated to the Kassite period.[110]

Mythology

Enlil and Ninlil

Ninlil appears in the myth Enlil and Ninlil.[26] Most of the known copies come from Nippur, though it was apparently also known in Sippar.[111] In the beginning Ninlil, portrayed as inexperienced, is warned by her mother, in this composition named Nunbaršegunu,[31] to avoid the advances of Enlil.[26] After encountering him, Ninlil initially resists, but after consulting his advisor Nuska Enlil accomplishes his goal and seduces and impregnates her.[26] For his transgression, he has to be judged by the "fifty great gods" and "the seven gods of destinies."[112] According to Wilfred G. Lambert, both terms are rare in Mesopotamian religious literature, and presumably refer to major deities of the pantheon treated as a group.[112] They deem him ritually impure and exile him from Nippur.[26] It is a matter of ongoing debate in scholarship if Enlil's crime was rape or merely premarital sex resulting in deflowering.[113] Ninlil follows him during his exile, even though he refuses to see her, and eventually ends up becoming pregnant multiple times,[114] giving birth to Nanna, Nergal, Ninazu and Enbilulu.[115] Alhena Gadotti argues that while the first encounter between them is arguably described as nonconsensual,[116] this does not seem to apply to the remaining three ones.[117] There is no indication that Enlil and Ninlil became husband and wife in the end, and only he receives praise in the closing lines of the composition.[118]

Ninlil's status in Enlil and Ninlil has been described as that of a "subordinate consort."[118] It has been pointed out that this portrayal does not appear to reflect her position in Mesopotamian religion, especially in the state pantheon of the Third Dynasty of Ur.[118] The absence of Ninurta among the children has also been noted.[31]

Enlil and Sud

Ninlil is also one of the main characters in the myth Enlil and Sud, also known as Marriage of Sud.[119] Due to the difference in her portrayal, it is sometimes contrasted with Enlil and Ninlil in scholarship.[26] It describes how she became Enlil's wife.[120] Copies are known from Nippur, Susa, Nineveh, Sultantepe and possibly Sippar.[121] Miguel Civil noted that the text had "wide diffusion attested not only by the relatively high number of sources preserved and their geographical distribution, but also by its long survival through Middle-Babylonian times and into the Assyrian libraries."[122] For uncertain reasons, no reference to Shuruppak is made as any point, and Sud lives with her mother Nisaba[99] in Eresh.[119]

In the beginning of the composition Enlil, who is portrayed as a young bachelor traveling to find a wife,[119] encounters Sud on the streets of Eresh and proposes to her.[123] However, he also calls her shameless.[119] She tells him to leave her sight in response,[119] and additionally remarks that past suitors made her mother angry with their dishonest offers.[123] Enlil consults his sukkal Nuska, and sends him to negotiate with Nisaba on his behalf.[123] He is tasked with listing various gifts Enlil can bestow upon her daughter if she will let him marry her.[123] Enlil also says that as his wife, Sud will be able to declare destinies the same way as he does.[123] Nisaba is happy with the offer and with Nuska's conduit, and agrees to the proposal, declaring that she will become Enlil's mother in law.[124] After Enlil keeps his promise and the gifts are delivered to Eresh, Nisaba blesses Sud.[125] Aruru, in this myth portrayed as Enlil's sister,[126] leads her to Nippur and helps her prepare for the wedding.[127] Sud and Enlil subsequently get married, and she received the name Ninlil,[127] promised to her in the beginning of the composition.[123] She is described as a former "no-name goddess" (Sumerian: dingir mu nu-tuku), but after assuming her new identity she is instead a goddess who "has a great name" (mu gal tuku).[99] It has also been argued that name Nintur is bestowed on her,[128] though Jeremy Black instead presumed that the goddess who receives it should be identified as Aruru, not Sud.[27] A short description of a sexual encounter between the newlyweds follows.[89] It has been compared to similar episodes in love songs.[89]

It has been suggested that the portrayal of Ninlil in Enlil and Sud was informed by her position in the state pantheon of the Third Dynasty of Ur.[118]

Other myths

Sud appears in some copies of Nanna-Suen's Journey to Nippur, though more known copies mention the goddess Ninirigal in the same passage instead.[61] Manfred Krebernik assumes this might indicate they were sometimes conflated.[10] Ninirigal, "lady of the Irigal," was the wife of Girra.[129] This goddess appears in association with healing deities such as Gula/Meme and Bau elsewhere, but contrary to conclusions in older scholarship shows no affinity with Inanna, despite also being associated with the territory of Uruk.[130]

Ninlil is mentioned in a myth only known from a single Old Babylonian fragment detailing the origin of the god Ishum.[131] He is described as a son of Ninlil and Shamash who was abandoned in the streets.[131] It is assumed that this myth represents a relic of the association between Sud, identified with Ninlil, and Sudaĝ, one of the names of the wife of sun god.[27] Ishum was usually regarded as the son of this couple instead.[27] Manfred Krebernik considers the composition to be the result of confusion between the names Sud and Sudaĝ, and thus between Ninlil and Ishum's mother, rather than syncretism.[132]

References

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 452.

- Wang 2011, pp. 14–15.

- Wang 2011, p. 14.

- Wang 2011, pp. 89–90.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 453.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 459.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 80.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 454.

- Peterson 2009, p. 72.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 455.

- Krebernik 2013a, p. 269.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 460.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 66.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 74–76.

- Zólyomi 2010, p. 419.

- Zólyomi 2010, p. 422.

- Zólyomi 2010, p. 423.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 63.

- Peterson 2009, p. 92.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 208–209.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 280.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 116.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 133.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 134.

- Metcalf 2019, p. 9.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 146.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 77.

- Archi 2004, p. 322.

- Taracha 2009, pp. 125–126.

- Taracha 2009, p. 126.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 456.

- Pongratz-Leisten 2015, p. 418.

- Krebernik 2011, p. 400.

- Porter 2004, p. 42.

- Porter 2004, pp. 43–44.

- Wang 2011, pp. 140–141.

- Peterson 2019, p. 60.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 69.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 83.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 67.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 458.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 87–90.

- Wiggermann 1998, p. 219.

- Lambert 1983, p. 389.

- Feliu 2003, p. 172.

- Wang 2011, p. 83.

- Peterson 2019, p. 59.

- Wiggermann 1998, p. 330.

- Schwemer 2001, p. 90.

- Krebernik 2005, p. 163.

- Zólyomi 2010, p. 427.

- Krebernik 2005, pp. 162–163.

- George 1993, p. 54.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 112.

- Westenholz 1997, pp. 58–59.

- George 1993, p. 49.

- George 1993, p. 52.

- Metcalf 2019, p. 15.

- Peterson 2020, p. 125.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 165.

- Krebernik 1998a, p. 457.

- McEwan 1998, p. 151.

- Peterson 2020, pp. 125–126.

- Peterson 2020, p. 126.

- Feliu 2007, pp. 92–93.

- Archi 2015, p. 634.

- Feliu 2003, p. 289.

- Feliu 2003, p. 230.

- Feliu 2003, p. 294.

- Feliu 2003, p. 246.

- Feliu 2003, p. 302.

- Tugendhaft 2016, p. 175.

- Tugendhaft 2016, pp. 177–178.

- Archi 2004, pp. 329–330.

- Wang 2011, pp. 84–85.

- George 1993, p. 112.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 101.

- George 1993, p. 153.

- George 1993, p. 106.

- George 1993, p. 117.

- George 1993, p. 148.

- George 1993, p. 127.

- George 1993, p. 65.

- George 1993, p. 161.

- Hilgert 2014, p. 183.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 27.

- George 1993, p. 151.

- Sharlach 2005, p. 22.

- Peterson 2019, p. 49.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 41.

- George 1993, p. 134.

- George 1993, p. 90.

- George 1993, p. 101.

- George 1993, p. 171.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 124.

- George 1993, p. 122.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 58.

- Such-Gutiérrez 2005, p. 31.

- Metcalf 2019, p. 10.

- Metcalf 2019, pp. 10–11.

- Metcalf 2019, p. 11.

- George 1993, p. 75.

- George 1993, p. 110.

- Metcalf 2019, p. 17.

- George 1993, p. 141.

- George 1993, p. 143.

- Streck 2013, p. 334.

- Lambert 2013, p. 286.

- George 1993, p. 22.

- George 1993, p. 6.

- Viano 2016, p. 37.

- Lambert 2013, p. 194.

- Gadotti 2009, p. 73.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 146–147.

- Wiggermann 1998a, p. 330.

- Gadotti 2009, p. 79.

- Gadotti 2009, p. 81.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 147.

- Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 145.

- Civil 2017, p. 423.

- Viano 2016, p. 41.

- Civil 2017, p. 421.

- Civil 2017, p. 443.

- Civil 2017, pp. 443–444.

- Civil 2017, p. 445.

- Civil 2017, p. 448.

- Civil 2017, p. 446.

- Lambert 2017, p. 453.

- Krebernik 1998, pp. 386–387.

- Krebernik 1998, p. 387.

- George 2015, p. 7.

- Krebernik 2013, p. 242.

Bibliography

- Archi, Alfonso (2004). "Translation of Gods: Kumarpi, Enlil, Dagan/NISABA, Ḫalki". Orientalia. GBPress- Gregorian Biblical Press. 73 (4): 319–336. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43078173. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- Archi, Alfonso (2015). Ebla and Its Archives. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9781614517887. ISBN 978-1-61451-716-0.

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- Civil, Miguel (2017) [1983]. "Enlil and Ninlil: the Marriage of Sud". Studies in Sumerian Civilization. Selected writings of Miguel Civil. Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-9168-237-0. OCLC 1193017085.

- Feliu, Lluís (2003). The god Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. Leiden Boston, MA: Brill. ISBN 90-04-13158-2. OCLC 52107444.

- Feliu, Lluís (2007). "Two brides for two gods. The case of Šala and Šalaš". He unfurrowed his brow and laughed. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-934628-32-8. OCLC 191759910.

- Gadotti, Alhena (2009). "Why It was Rape: The Conceptualization of Rape in Sumerian Literature". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 129 (1): 73–82. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 40593869. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- George, Andrew R. (2015). "The Gods Išum and Ḫendursanga: Night Watchmen and Street-lighting in Babylonia". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. 74 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1086/679387. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 161546618.

- Hilgert, Markus (2014), "Tummal", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-25

- Krebernik, Manfred (1998), "Nin-irigala", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-23

- Krebernik, Manfred (1998a), "Ninlil", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-25

- Krebernik, Manfred (2005), "Pabilsaĝ(a)", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-25

- Krebernik, Manfred (2011), "Šerū'a", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-24

- Krebernik, Manfred (2013), "Sudaĝ", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-24

- Krebernik, Manfred (2013a), "Šukurru(m)", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-26

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1983), "Kutušar", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-23

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (2013). Babylonian creation myths. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-861-9. OCLC 861537250.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (2017). "Appendix. Further Notes on Enlil and Ninlil: the Marriage of Sud". Studies in Sumerian Civilization. Selected writings of Miguel Civil. Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona. pp. 452–454. ISBN 978-84-9168-237-0.

- McEwan, Gilbert J. P. (1998), "Nanibgal", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-25

- Metcalf, Christopher (2019). Sumerian Literary Texts in the Schøyen Collection. Penn State University Press. doi:10.1515/9781646020119. ISBN 978-1-64602-011-9. S2CID 241160992.

- Peterson, Jeremiah (2009). God lists from Old Babylonian Nippur in the University Museum, Philadelphia. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-019-7. OCLC 460044951.

- Peterson, Jeremiah (2019). "The Sexual Union of Enlil and Ninlil: an uadi Composition of Ninlil". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. De Gruyter. 109 (1): 48–61. doi:10.1515/za-2019-0002. ISSN 0084-5299. S2CID 199546991.

- Peterson, Jeremiah (2020). "Christopher Metcalf: Sumerian Literary Texts in the Schøyen Collection, Volume 1: Literary Sources on Old Babylonian Religion. (Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology 38) (review)". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. De Gruyter. 111 (1). doi:10.1515/za-2020-0025. ISSN 1613-1150.

- Pongratz-Leisten, Beate (2015). Religion and Ideology in Assyria. Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records (SANER). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-426-8. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- Porter, Barbara Nevling (2004). "Ishtar of Nineveh and Her Collaborator, Ishtar of Arbela, in the Reign of Assurbanipal". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 66: 41–44. doi:10.2307/4200556. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200556. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2001). Die Wettergottgestalten Mesopotamiens und Nordsyriens im Zeitalter der Keilschriftkulturen: Materialien und Studien nach den schriftlichen Quellen (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04456-1. OCLC 48145544.

- Sharlach, Tonia (2005). "Diplomacy and the Rituals of Politics at the Ur III Court". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. American Schools of Oriental Research. 57: 17–29. doi:10.1086/JCS40025987. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 40025987. S2CID 157934313. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- Streck, Michael P. (2013), "Šuruppag A. Philologisch", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-05-28

- Such-Gutiérrez, Marcos (2005). "Untersuchungen zum Pantheon von Adab im 3. Jt". Archiv für Orientforschung (in German). Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO)/Institut für Orientalistik. 51: 1–44. ISSN 0066-6440. JSTOR 41670228. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- Taracha, Piotr (2009). Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447058858.

- Tugendhaft, Aaron (2016). "Gods on clay: Ancient Near Eastern scholarly practices and the history of religions". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W. (eds.). Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316226728.009.

- Viano, Maurizio (2016). The reception of Sumerian literature in the western periphery. Venezia. ISBN 978-88-6969-077-8. OCLC 965932920.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wang, Xianhua (2011). The metamorphosis of Enlil in early Mesopotamia. Münster. ISBN 978-3-86835-052-4. OCLC 712921671.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (1997). "Nanaya: Lady of Mystery". In Finkel, I. L.; Geller, M. J. (eds.). Sumerian Gods and their Representations. STYX Publications. ISBN 978-90-56-93005-9.

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1998), "Nergal A. Philological", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-23

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1998a), "Nin-azu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-05-26

- Zólyomi, Gabor (2010). "Hymns to Ninisina and Nergal on the Tablets Ash 1911.235 and Ni 9672". Your praise is sweet : a memorial volume for Jeremy Black from students, colleagues and friends. London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq. ISBN 978-0-903472-28-9. OCLC 612335579.

External links

- Enlil and Ninlil in the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- Enlil and Sud in the ETCSL

- An adab to Ninlil (Ninlil A) in the ETCSL

- The Temple Hymns in the ETCSL

- Nanna-Suen's Journey to Nippur in the ETCSL

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg.webp)