Suicide prevention

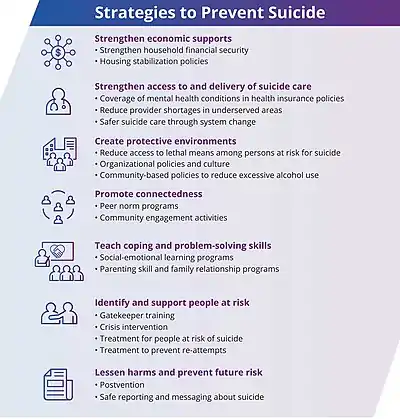

Suicide prevention is a collection of efforts to reduce the risk of suicide.[1] Suicide is often preventable,[2] and the efforts to prevent it may occur at the individual, relationship, community, and society level.[1] Suicide is a serious public health problem that can have long-lasting effects on individuals, families, and communities. Preventing suicide requires strategies at all levels of society. This includes prevention and protective strategies for individuals, families, and communities. Suicide can be prevented by learning the warning signs, promoting prevention and resilience, and committing to social change.[3]

Beyond direct interventions to stop an impending suicide, methods may include:

- treating mental illness

- improving coping strategies of people who are at risk

- reducing risk factors for suicide, such as substance misuse, poverty and social vulnerability

- giving people hope for a better life after current problems are resolved

- calling a suicide hotline number

General efforts include measures within the realms of medicine, mental health, and public health. Because protective factors[4] such as social support and social engagement—as well as environmental risk factors such as access to lethal means— play a role in suicide, suicide is not solely a medical or mental-health issue.[5]

Interventions

Lethal-means reduction

.jpg.webp)

Means reduction — reducing the odds that a person attempting suicide will use highly lethal means — is an important component of suicide prevention.[6] This practice is also called "means restriction". It has been demonstrated that restricting lethal means can help reduce suicide rates, as delaying action until the desire to die has passed.[7] In general, strong evidence supports the effectiveness of means restriction in preventing suicides.[8][9][10][11] There is also strong evidence that restricted access at so-called suicide hotspots, such as bridges and cliffs, reduces suicides, whereas other interventions such as placing signs or increasing surveillance at these sites appears less effective.[12]

One of the most famous historical examples of means reduction is that of coal gas in the United Kingdom. Until the 1950s, the most common means of suicide in the UK was poisoning by gas inhalation. In 1958, natural gas (virtually free of carbon monoxide) was introduced, and over the next decade, comprised over 50% of gas used. As carbon monoxide in gas decreased, suicides also decreased. The decrease was driven entirely by dramatic decreases in the number of suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning.[13][14] A 2020 Cochrane review on means restrictions for jumping found tentative evidence of reductions in frequency.[15]

In the United States, firearm access is associated with increased suicide completion.[16] About 85% of suicide attempts with a gun result in death, while most other widely used suicide attempt methods result in death less than 5% of the time.[16][17] Matthew Miller, M.D., Sc.D. conducted research comparing the number of suicides in states with the highest rates of gun ownership, to the number of suicides in states with the lowest rates of gun ownership. He found that men were 3.7 times more likely to die by firearm suicide and women were 7.9 times more likely to die by firearm suicide living in states with high rates of gun ownership. There was no difference in non-firearm suicides.[18] Although restrictions on access to firearms have reduced firearm suicide rates in other countries, such restrictions are difficult in the United States because the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution limits restrictions on weapons.[19]

Crisis hotline

Crisis hotlines connect a person in distress to either a volunteer or staff member.[2] This may occur via telephone, online chat, or in person.[2] Even though crisis hotlines are common, they have not been well studied.[20][21] One study found a decrease in psychological pain, hopelessness, and desire to die from the beginning of the call through the next few weeks; however, the desire to die did not decrease long term.[2]

Diet

About 50% of people who die of suicide have a mood disorder such as major depression.[22][23] Sleep and diet may play a role in depression (major depressive disorder), and interventions in these areas may be an effective add-on to conventional methods.[24] Vitamin B2, B6 and B12 deficiency may cause depression in females.[25]

Vitamin B12, for humans, is the only vitamin that must be sourced from animal-derived foods or from supplements.[26][27] Only some archaea and bacteria can synthesize vitamin B12.[28] Foods containing vitamin B12 include meat, clams, liver, fish, poultry, eggs, and dairy products.[26] Many breakfast cereals are fortified with the vitamin.[26] Natural sources of Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) include meat, fish and fowl, eggs, dairy products, green vegetables, mushrooms, and almonds.[29] Sources of Vitamin B6 include (most values shown are rounded to nearest tenth of a milligram):

| Source[30][31] | Amount (mg per 100 grams) |

|---|---|

| Whey protein concentrate | 1.2 |

| Beef liver, pan-fried | 1.0 |

| Tuna, skipjack, cooked | 1.0 |

| Beef steak, grilled | 0.9 |

| Salmon, Atlantic, cooked | 0.9 |

| Chicken breast, grilled | 0.7 |

| Pork chop, cooked | 0.6 |

| Turkey, ground, cooked | 0.6 |

| Banana | 0.4 |

| Source[30][31] | Amount (mg per 100 grams) |

|---|---|

| Mushroom, Shiitake, raw | 0.3 |

| Potato, baked, with skin | 0.3 |

| Sweet potato baked | 0.3 |

| Bell pepper, red | 0.3 |

| Peanuts | 0.3 |

| Avocado | 0.25 |

| Spinach | 0.2 |

| Chickpeas | 0.1 |

| Tofu, firm | 0.1 |

| Source[31] | Amount (mg per 100 grams) |

|---|---|

| Corn grits | 0.1 |

| Milk, whole | 0.1 (one cup) |

| Yogurt | 0.1 (one cup) |

| Almonds | 0.1 |

| Bread, whole wheat/white | 0.2/0.1 |

| Rice, cooked, brown/white | 0.15/0.02 |

| Beans, baked | 0.1 |

| Beans, green | 0.1 |

| Chicken egg | 0.1 |

More information about food (e.g. oily fish with omega-3 fats, a class of PUFA), drink (e.g. water), healthy diet and mental health can also be found on the website of Healthdirect, the national health advice service in Australia.[32]

Social intervention

In the United States, the 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention promotes various specific suicide prevention efforts including:[33]

- Developing groups led by professionally trained individuals for broad-based support for suicide prevention.

- Promoting community-based suicide prevention programs.

- Screening and reducing at-risk behavior through psychological resilience programs that promotes optimism and connectedness.

- Education about suicide, including risk factors, warning signs, stigma related issues and the availability of help through social campaigns.

- Increasing the proficiency of health and welfare services at responding to people in need. e.g., sponsored training for helping professionals, increased access to community linkages, employing crisis counseling organizations.

- Reducing domestic violence and substance abuse through legal and empowerment means are long-term strategies.

- Reducing access to convenient means of suicide and methods of self-harm. e.g., toxic substances, poisons, handguns.

- Reducing the quantity of dosages supplied in packages of non-prescription medicines e.g., aspirin.

- School-based competency promoting and skill enhancing programs.

- Interventions and usage of ethical surveillance systems targeted at high-risk groups.

- Improving reporting and portrayals of negative behavior, suicidal behavior, mental illness and substance abuse in the entertainment and news media.

- Research on protective factors & development of effective clinical and professional practices.

Media guidelines

Recommendations around media reporting of suicide include not sensationalizing the event or attributing it to a single cause.[2] It is also recommended that media messages include suicide prevention messages such as stories of hope and links to further resources.[2][34] Particular care is recommended when the person who died is famous.[35] Including specific details of the method or the location is not recommended.[35]

There is little evidence, however, regarding the benefit of providing resources for those looking for help and the evidence for media guidelines generally is mixed at best.[36]

TV shows and news media may also be able to help prevent suicide by linking suicide with negative outcomes such as pain for the person who has attempted suicide and their survivors, conveying that the majority of people choose something other than suicide in order to solve their problems, avoiding mentioning suicide epidemics, and avoiding presenting authorities or sympathetic, ordinary people as spokespersons for the reasonableness of suicide.[37]

Medication

The medication lithium may be useful in certain situations to reduce the risk of suicide.[38] Specifically it is effective at lowering the risk of suicide in those with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.[38][39] Some antidepressant medications may increase suicidal ideation in some patients under certain conditions.[40] Medication is often used as a powerful and helpful tool for many struggling in mental health conditions. It can help with depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts and ideations. There are many different types of medications you can take for mental health, and the variety of medications helps a diverse amount of people find the right medications for them. They have anti-depression, anti- anxiety, anti- psychotics, stimulants, mood stabilizers, and all kinds of SSRI medications. This can help a person tremendously in treating their mental health conditions. And improving the quality of their life. This can reduce the risk of suicidal tendencies, ideations, and thoughts. Finding the right medication for the individual can be lifesaving. Those who struggle with deep suicidal crisis can highly benefit from having medication be part of their suicide prevention plan, and mental health improvement plan. It is a tool that is often paired with therapy and other beneficial resources.

Counseling

There are multiple talking therapies that reduce suicidal thoughts and behaviors including dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).[41][42] Cognitive behavior therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP) is a form of DBT adapted for adolescents at high risk for repeated suicide attempts.[43][44] The brief intervention and contact technique developed by the World Health Organization also has shown benefit.[45]

The World Health Organization recommends "specific skills should be available in the education system to prevent bullying and violence in and around the school".[46]

Coping planning

Coping planning is a strengths-based intervention that aims to meet the needs of people who ask for help, including those experiencing suicidal ideation.[47] By addressing why someone asks for help, the risk assessment and management stays on what the person needs, and the needs assessment focuses on the individual needs of each person.[48][49] The coping planning approach to suicide prevention draws on the health-focused theory of coping. Coping is normalized as a normal and universal human response to unpleasant emotions, and interventions are considered a change continuum of low intensity (e.g., self-soothing) to high intensity support (e.g. professional help). By planning for coping, it supports people who are distressed and provides a sense of belongingness and resilience in treatment of illness.[50][51] The proactive coping planning approach overcomes implications of ironic process theory.[52] The biopsychosocial[53] strategy of training people in healthy coping improves emotional regulation and decreases memories of unpleasant emotions.[54] A good coping planning strategically reduces the inattentional blindness for a person while developing resilience and regulation strengths.[50]

Strategies

The traditional approach has been to identify the risk factors that increase suicide or self-harm, though meta-analysis studies suggest that suicide risk assessment might not be useful and recommend immediate hospitalization of the person with suicidal feelings as the healthy choice.[55] In 2001, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, published the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, establishing a framework for suicide prevention in the U.S. The document, and its 2012 revision, calls for a public health approach to suicide prevention, focusing on identifying patterns of suicide and suicidal ideation throughout a group or population (as opposed to exploring the history and health conditions that could lead to suicide in a single individual).[56] The ability to recognize warning signs of suicide allows individuals who may be concerned about someone they know to direct them to help.[57]

Suicide gesture and suicidal desire (a vague wish for death without any actual intent to kill oneself) are potentially self-injurious behaviors that a person may use to attain some other ends, like to seek help, punish others, or to receive attention. This behavior has the potential to aid an individual's capability for suicide and can be considered as a suicide warning, when the person shows intent through verbal and behavioral signs.[58]

Specific strategies

Suicide prevention strategies focus on reducing the risk factors and intervening strategically to reduce the level of risk. Risk and protective factors unique to the individual can be assessed by a qualified mental health professional.

Some of the specific strategies used to address are:

- Crisis intervention.

- Structured counseling and psychotherapy.

- Hospitalization for those with low adherence to collaboration for help and those who require monitoring and secondary symptom treatment.

- Supportive therapy like substance abuse treatment, Psychotropic medication, Family psychoeducation and Access to emergency phone call care with emergency rooms, suicide prevention hotlines, etc.

- Restricting access to lethality of suicide means through policies and laws.

- Creating and using crisis cards, an easy-to-read uncluttered card that describes a list of activities one should follow in crisis until the positive behavior responses settles in the personality.

- Person-centered life skills training. e.g., Problem solving.

- Registering with support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, Suicide Bereavement Support Group, a religious group with flow rituals, etc.

- Therapeutic recreational therapy that improves mood.

- Motivating self-care activities like physical exercises and meditative relaxation.

Psychotherapies that have shown most successful or evidence based are dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which has shown to be helpful in reducing suicide attempts and reducing hospitalizations for suicidal ideation[60] and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which has shown to improve problem-solving and coping abilities.[61]

After a suicide

Postvention is for people affected by an individual's suicide. This intervention facilitates grieving, guides to reduce guilt, guides to reduce anxiety and depression, and helps to decrease the effects of trauma. Bereavement is ruled out and promoted for catharsis and supporting their adaptive capacities before intervening depression and any psychiatric disorders. Postvention is also provided to minimize the risk of imitative or copycat suicides, but there is a lack of evidence based standard protocol. The general goal of the mental health practitioner is to decrease the likelihood of others identifying with the suicidal behavior of the deceased as a coping strategy in dealing with adversity.[62]

Risk assessment

Warning signs

Warning signs of suicide can allow individuals to direct people who may be considering suicide to get help.[63]

Behaviors that may be warning signs include:[64]

- Talking about wanting to die or wanting to kill themselves

- Suicidal ideation: thinking, talking, or writing about suicide, planning for suicide

- Substance abuse

- Feelings of purposelessness

- Anxiety, agitation, being unable to sleep, or sleeping all the time

- Feelings of being trapped

- Feelings of hopelessness

- Social withdrawal

- Displaying extreme mood swings, suddenly changing from sad to very calm or happy

- Recklessness or impulsiveness, taking risks that could lead to death, such as driving extremely fast

- Mood changes including depression

- Feelings of uselessness

- Settling outstanding affairs, giving away prized or valuable possessions, or making amends when they are otherwise not expected to die (as an example, this behavior would be typical in a terminal cancer patient but not a healthy young adult)

- Strong feelings of pain, either emotional or physical

- Considering oneself burdensome

- Increased use of drugs or alcohol

Additionally, the National Institute for Mental Health includes feeling burdensome, and strong feelings of pain—either emotional or physical—as warning signs that someone may attempt suicide.[63]

Direct talks

An effective way to assess suicidal thoughts is to talk with the person directly, to ask about depression, and assess suicide plans as to how and when it might be attempted.[65] Contrary to popular misconceptions, talking with people about suicide does not plant the idea in their heads.[65] However, such discussions and questions should be asked with care, concern and compassion.[65] The tactic is to reduce sadness and provide assurance that other people care. The WHO advises to not say everything will be all right nor make the problem seem trivial, nor give false assurances about serious issues.[65] The discussions should be gradual and specifically executed when the person is comfortable about discussing their feelings. ICARE (Identify the thought, Connect with it, Assess evidence for it, Restructure the thought in positive light, Express or provide room for expressing feelings from the restructured thought) is a model of approach used here.[65]

Screening

The U.S. Surgeon General has suggested that screening to detect those at risk of suicide may be one of the most effective means of preventing suicide in children and adolescents.[66] There are various screening tools in the form of self-report questionnaires to help identify those at risk such as the Beck Hopelessness Scale and Is Path Warm?. A number of these self-report questionnaires have been tested and found to be effective for use among adolescents and young adults.[67] There is however a high rate of false-positive identification and those deemed to be at risk should ideally have a follow-up clinical interview.[68] The predictive quality of these screening questionnaires has not been conclusively validated so it is not possible to determine if those identified at risk of suicide will actually die by suicide.[69] Asking about or screening for suicide does not create or increase the risk.[70]

In approximately 75 percent of suicides, the individuals had seen a physician within the year before their death, including 45 to 66 percent within the prior month. Approximately 33 to 41 percent of those who died by suicide had contact with mental health services in the prior year, including 20 percent within the prior month. These studies suggest an increased need for effective screening.[71][72][73][74][75] Many suicide risk assessment measures are not sufficiently validated, and do not include all three core suicidality attributes (i.e., suicidal affect, behavior, and cognition).[76] A study published by the University of New South Wales has concluded that asking about suicidal thoughts cannot be used as a reliable predictor of suicide risk.[77]

Underlying condition

The conservative estimate is that 10% of individuals with psychiatric disorders may have an undiagnosed medical condition causing their symptoms,[78] with some estimates stating that upwards of 50% may have an undiagnosed medical condition which, if not causing, is exacerbating their psychiatric symptoms.[79][80] Illegal drugs and prescribed medications may also produce psychiatric symptoms.[81] Effective diagnosis and, if necessary, medical testing, which may include neuroimaging[82] to diagnose and treat any such medical conditions or medication side effects, may reduce the risk of suicidal ideation as a result of psychiatric symptoms. Most often including depression, which are present in up to 90–95% of cases.[83]

Risk factors

All people can be at risk of suicide. Risk factors that contribute to someone feeling suicidal or making a suicide attempt may include:

- Depression, other mental disorders, or substance abuse disorder

- Certain medical conditions

- Chronic pain[84]

- A prior suicide attempt

- Family history of a mental disorder or substance abuse

- Family history of suicide

- Family violence, including physical or sexual abuse

- Psychiatric Abuse

- Benzodiazepines

- Having guns or other firearms in the home

- Having recently been released from prison, jail or mental asylum

- Self-harm

- Being exposed to others' suicidal behavior, such as that of family members, peers, or celebrities[64]

- Being male[85]

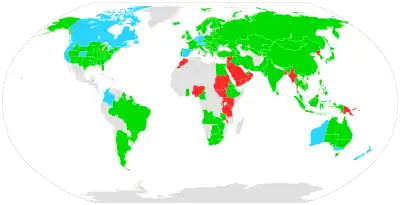

Legislation

Suicide is a crime in some parts of the world.[86] However, while suicide has been decriminalized in many countries, the act is almost universally stigmatized and discouraged. In some contexts, suicide could be utilized as an extreme expression of liberty, as is exemplified by its usage as an expression of devout dissent towards perceived tyranny or injustice which occurred occasionally in cultures such as ancient Rome, medieval Japan, or today's Tibet Autonomous Region.

While a person who has died of suicide is beyond the reach of the law, there can still be legal consequences in relation to treatment of the corpse or the fate of the person's property or family members. The associated matters of assisting a suicide and attempting suicide have also been dealt with by the laws of some jurisdictions. Some countries criminalise suicide attempts.

Support organizations

Many non-profit organizations exist, such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention in the United States, which serve as crisis hotlines; it has benefited from at least one crowd-sourced campaign.[87] The first documented program aimed at preventing suicide was initiated in 1906 in both New York, the National Save-A-Life League, and in London, the Suicide Prevention Department of the Salvation Army.[88]

Suicide prevention interventions fall into two broad categories: prevention targeted at the level of the individual and prevention targeted at the level of the population.[89] To identify, review, and disseminate information about best practices to address specific objectives of the National Strategy Best Practices Registry (BPR) was initiated. The Best Practices Registry of Suicide Prevention Resource Center is a registry of various suicide intervention programs maintained by the American Association of Suicide Prevention. The programs are divided, with those in Section I listing evidence-based programs: interventions which have been subjected to in depth review and for which evidence has demonstrated positive outcomes. Section III programs have been subjected to review.[90][91]

Examples of support organizations

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

- Befrienders Worldwide

- Campaign Against Living Miserably

- Crisis Text Line

- International Association for Suicide Prevention

- The Jed Foundation

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- Samaritans

- Suicide Prevention Action Network USA

- Trans Lifeline

- The Trevor Project

Economics

Although there are lasting emotional effects on families due to suicide, the economic effects are contagious. In the United States it is estimated that an episode of suicide results in costs of about $1.3 million.[92] 97 percent of these costs are due to the loss in career productivity from the deceased individual as well as the after-effect toll on families. Likewise, the remaining 3 percent of the expenses were contributed from medical expenses. Money spent on appropriated interventions is estimated to result in a decrease in economic losses that are 2.5-fold greater than the amount spent. Therefore, declaring the need for increased actions in intervention and prevention to help uphold individuals, families, and the economy.[92]

See also

References

- "Suicide | Violence Prevention | Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices (PDF). CDC. 2017. p. 7. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Prevention Strategies". www.cdc.gov. 2021-06-04. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- "Maine Suicide Prevention Website". Maine.gov. Archived from the original on 2006-07-11. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

Protective Factors are the positive conditions, personal and social resources that promote resiliency and reduce the potential for youth suicide as well as other related high-risk behaviors. Just as suicide risks rise from an interaction between familial, genetic, and environmental factors, so do protective factors.

- Compare: "Suicide prevention definition – Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms". Medterms.com. 2003-09-16. Archived from the original on 2003-08-19. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

Suicide should not be viewed solely as a medical or mental health problem, since protective factors such as social support and connectedness appear to play significant roles in the prevention of death.

- "Means Matter". Harvard School of Public Health. Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- "Reduce Access to Means of Suicide". Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Archived from the original on 2019-05-16. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Yip, Paul SF; Caine, Eric; Yousuf, Saman; Chang, Shu-Sen; Wu, Kevin Chien-Chang; Chen, Ying-Yeh (June 2012). "Means restriction for suicide prevention". The Lancet. 379 (9834): 2393–2399. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. PMC 6191653. PMID 22726520.

- Reisch, T; Steffen, T; Habenstein, A; Tschacher, W (September 2013). "Change in suicide rates in Switzerland before and after firearm restriction resulting from the 2003 "Army XXI" reform". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (9): 977–84. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12091256. PMID 23897090.

- Rosenbaum, Janet (2012). "Gun utopias? Firearm access and ownership in Israel and Switzerland". Journal of Public Health Policy. 33 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1057/jphp.2011.56. PMC 3267868. PMID 22089893.

- Knipe, Duleeka (2017). "Suicide prevention through means restriction: Impact of the 2008-2011 pesticide restrictions on suicide in Sri Lanka". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0172893. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1272893K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172893. PMC 5338785. PMID 28264041.

- Cox, Georgina R; Owens, Christabel; Robinson, Jo; Nicholas, Angela; Lockley, Anne; Williamson, Michelle; Cheung, Yee Tak Derek; Pirkis, Jane (December 2013). "Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review". BMC Public Health. 13 (1): 214. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-214. PMC 3606606. PMID 23496989.

- "Means Matter – Means Reduction Saves Lives". Harvard School of Public Health. Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- Kreitman, N (Jun 1976). "The Coal Gas Story: United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960–1971". Br J Prev Soc Med. 30 (2): 86–93. doi:10.1136/jech.30.2.86. PMC 478945. PMID 953381.

- Okolie, Chukwudi; Wood, Suzanne; Hawton, Keith; Kandalama, Udai; Glendenning, Alexander C; Dennis, Michael; Price, Sian F; Lloyd, Keith; John, Ann (25 February 2020). "Means restriction for the prevention of suicide by jumping". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (2): CD013543. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013543. PMC 7039710. PMID 32092795.

- "Means Matter – Firearm Access is a Risk Factor for Suicide". Harvard School of Public Health. Archived from the original on 2012-12-13. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

About 85% of attempts with a firearm are fatal: that's a much higher case fatality rate than for nearly every other method. Many of the most widely used suicide attempt methods have case fatality rates below 5%.

- Vyrostek, Sara B.; Annest, Joseph L.; Ryan, George W. (3 September 2004). "Surveillance for fatal and nonfatal injuries--United States, 2001". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 53 (7): 1–57. PMID 15343143.

- Miller, M.; Hemenway, D. (2008). "Guns and Suicide in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (10): 989–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0805923. PMID 18768940.

- Mann, J. John; Michel, Christina A. (October 2016). "Prevention of Firearm Suicide in the United States: What Works and What Is Possible". American Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (10): 969–979. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010069. PMID 27444796.

- Sakinofsky I (June 2007). "The current evidence base for the clinical care of suicidal patients: strengths and weaknesses". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 52 (6 Suppl 1): 7S–20S. PMID 17824349.

Other suicide prevention strategies that have been considered are crisis centres and hotlines, method control, and media education... There is minimal research on these strategies. Even though crisis centres and hotlines are used by suicidal youth, information about their impact on suicidal behaviour is lacking.

- Zalsman, Gil; Hawton, Keith; Wasserman, Danuta; van Heeringen, Kees; Arensman, Ella; Sarchiapone, Marco; Carli, Vladimir; Höschl, Cyril; Barzilay, Ran; Balazs, Judit; Purebl, György; Kahn, Jean Pierre; Sáiz, Pilar Alejandra; Lipsicas, Cendrine Bursztein; Bobes, Julio; Cozman, Doina; Hegerl, Ulrich; Zohar, Joseph (July 2016). "Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review". The Lancet Psychiatry. 3 (7): 646–659. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. PMID 27289303.

Other approaches that need further investigation include gatekeeper training, education of physicians, and internet and helpline support.

- Barlow, David H.; Durand, Vincent Mark (2005). Abnormal Psychology. Wadsworth Publishing Company. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-534-63356-1.

- Bachmann S (6 July 2018). "Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (7): 1425. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071425. PMC 6068947. PMID 29986446.

Half of all completed suicides are related to depressive and other mood disorders

- Lopresti AL, Hood SD, Drummond PD (May 2013). "A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise" (PDF). Journal of Affective Disorders. 148 (1): 12–27. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.014. PMID 23415826. S2CID 22218602. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2017.

- Wu Y, Zhang L, Li S, Zhang D (29 April 2021). "Associations of dietary vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 with the risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. Oxford University Press (OUP). 80 (3): 351–366. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab014. ISSN 0029-6643. PMID 33912967.

- Office of Dietary Supplements (6 April 2021). "Vitamin B12: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Bethesda, Maryland: US National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- Vincenti A, Bertuzzo L, Limitone A, D'Antona G, Cena H (June 2021). "Perspective: Practical Approach to Preventing Subclinical B12 Deficiency in Elderly Population". Nutrients. 13 (6): 1913. doi:10.3390/nu13061913. PMC 8226782. PMID 34199569.

- Watanabe F, Bito T (January 2018). "Vitamin B12 sources and microbial interaction". Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 243 (2): 148–158. doi:10.1177/1535370217746612. PMC 5788147. PMID 29216732.

- "Riboflavin: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 11 May 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- Joseph, Michael (10 January 2021). "30 Foods High In Vitamin B6". Nutrition Advance. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

All nutritional values within this article have been sourced from the USDA's FoodData Central Database.

- "USDA Food Data Central. Standard Reference, Legacy Foods". USDA Food Data Central. April 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- "Food, drink and mental health". healthdirect. Retrieved 25 Aug 2023.

- General (US), Office of the Surgeon; Prevention (US), National Action Alliance for Suicide (2012). Introduction. US Department of Health & Human Services (US). Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Recommendations". Reporting on Suicide. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Preventing suicide: a resource for media professionals. WHO. 2017. p. viii. hdl:10665/258814.

- Stack, Steven (October 2020). "Media guidelines and suicide: A critical review". Social Science & Medicine. 262: 112690. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112690. PMID 32067758. S2CID 211159266.

- R. F. W. Diekstra. Preventive strategies on suicide.

- Smith, Katharine A; Cipriani, Andrea (November 2017). "Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: Updated meta-review of the scientific literature". Bipolar Disorders. 19 (7): 575–586. doi:10.1111/bdi.12543. PMID 28895269. S2CID 39221887.

- Coppen A (2000). "Lithium in unipolar depression and the prevention of suicide". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (Suppl 9): 52–6. PMID 10826662.

- Teicher, Martin H.; Glod, Carol A.; Cole, Jonathan O. (March 1993). "Antidepressant Drugs and the Emergence of Suicidal Tendencies". Drug Safety. 8 (3): 186–212. doi:10.2165/00002018-199308030-00002. PMID 8452661. S2CID 36366654.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs Technologies in Health (CADTH) (1 March 2010). "Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in Adolescents for Suicide Prevention: Systematic Review of Clinical-Effectiveness". CADTH Technology Overviews. 1 (1): e0104. PMC 3411135. PMID 22977392.

- National Institute of Mental Health: Suicide in the U.S.: Statistics and Prevention

- Stanley B, Brown G, Brent DA, et al. (October 2009). "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 48 (10): 1005–13. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbfe. PMC 2888910. PMID 19730273.

- Kairi Kõlves; Diego De Leo. "Child and youth suicides: Research and Potentials for Prevention" (PDF). Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2016.

- Riblet, NBV; Shiner, B; Young-Xu, Y; Watts, BV (June 2017). "Strategies to prevent death by suicide: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". British Journal of Psychiatry. 210 (6): 396–402. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187799. PMID 28428338.

- Preventing suicide: a resource for teachers and other school staff. World Health Organization. 2000. hdl:10665/66801.

- Stallman, H. M. (2018). "Coping Planning: A patient- and strengths-focused approach to suicide prevention training". Australasian Psychiatry. 26 (2): 141–144. doi:10.1177/1039856217732471. PMID 28967263. S2CID 4527243.

- Stallman, H. M. (2017). "Meeting the needs of patients who have suicidal thoughts presenting to Emergency Departments". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 29 (6): 749. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.12867. PMID 28940744. S2CID 206925361.

- Franklin, JC; Ribeiro, JD; Fox, KR (2016). "Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research". Psychol Bull. 143 (2): 187–232. doi:10.1037/bul0000084. PMID 27841450. S2CID 3941854.

- Stallman, H. M.; Wilson, C. J. (2018). "Can the mental health of Australians be improved by dual strategy for promotion and prevention?". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 52 (6): 602. doi:10.1177/0004867417752070. PMID 29320871. S2CID 38696679.

- Stallman, H. M.; Ohan, J. L. (2018). "The alignment of law, practice and need in suicide prevention". BJPsych Bulletin. 42 (2): 51–53. doi:10.1192/bjb.2017.3. PMC 6001851. PMID 29455707.

- Wegner, Daniel M. (1989). White Bears and Other Unwanted Thoughts: Suppression, Obsession, and the Psychology of Mental Control. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0670825226

- Engel, G. L. (1980). "The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model". American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (5): 535–544. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. PMID 7369396.

- Katsumi, Y.; Dolcos, S. (2018). "Suppress to feel and remember less: Neural correlates of explicit and implicit emotional suppression on perception and memory". Neuropsychologia. 145: 106683. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.02.010. PMID 29432767. S2CID 3628693.

- Murray, Declan; Devitt, Patrick. "Suicide Risk Assessment Doesn't Work". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "National Strategy for Suicide Prevention" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- "Suicide Prevention". NIMH. August 2021.

- Shahar, Golan; Bareket, Liad; Rudd, M. David; Joiner, Thomas E. (July 2006). "In severely suicidal young adults, hopelessness, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation constitute a single syndrome". Psychological Medicine. 36 (7): 913–922. doi:10.1017/S0033291706007586. PMID 16650341. S2CID 37342106.

- "Preventing Suicide | Violence Prevention | Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Linehan et al., 2006

- Stellrecht et al., 2006

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (April 2001). "Summary of the Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Suicidal Behavior". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 40 (4): 495–499. doi:10.1097/00004583-200104000-00024. PMID 11314578. S2CID 1902038.

- "NIMH » Suicide Prevention". www.nimh.nih.gov. 19 July 2023.

- "Suicide Prevention". The National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Preventing Suicide – A Resource for Primary Health Care Workers" (PDF), World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000, p. 13.

- Office of the Surgeon General:The Surgeon General's Call To Action To Prevent Suicide 1999

- Rory C. O'Connor, Stephen Platt, Jacki Gordon: International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice, p. 510

- Rory C. O'Connor, Stephen Platt, Jacki Gordon, International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice, p.361; Wiley-Blackwell (2011), ISBN 0-470-68384-8

- Alan F. Schatzberg: The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of mood disorders, p. 503: American Psychiatric Publishing; (2005) ISBN 1-58562-151-X

- Crawford, MJ; Thana, L; Methuen, C; Ghosh, P; Stanley, SV; Ross, J; Gordon, F; Blair, G; Bajaj, P (May 2011). "Impact of screening for risk of suicide: randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 198 (5): 379–84. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083592. PMID 21525521.

- Depression and Suicide at eMedicine

- González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW (January 2010). "Depression Care in the United States: Too Little for Too Few". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. PMC 2887749. PMID 20048221.

- Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL (June 2002). "Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (6): 909–16. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. PMC 5072576. PMID 12042175.

- Lee HC, Lin HC, Liu TC, Lin SY (June 2008). "Contact of mental and nonmental health care providers prior to suicide in Taiwan: a population-based study". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 53 (6): 377–83. doi:10.1177/070674370805300607. PMID 18616858.

- Pirkis J, Burgess P (December 1998). "Suicide and recency of health care contacts. A systematic review". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (6): 462–74. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.6.462. PMID 9926074. S2CID 43144463.

- Harris K. M.; Syu J.-J.; Lello O. D.; Chew Y. L. E.; Willcox C. H.; Ho R. C. M. (2015). "The ABC's of suicide risk assessment: Applying a tripartite approach to individual evaluations". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0127442. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027442H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127442. PMC 4452484. PMID 26030590.

- McHugh, Catherine M.; Corderoy, Amy; Ryan, Christopher James; Hickie, Ian B.; Large, Matthew Michael (March 2019). "Association between suicidal ideation and suicide: meta-analyses of odds ratios, sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value". BJPsych Open. 5 (2): e18. doi:10.1192/bjo.2018.88. PMC 6401538. PMID 30702058.

- Hall RC, Popkin MK, Devaul RA, Faillace LA, Stickney SK (November 1978). "Physical illness presenting as psychiatric disease". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 35 (11): 1315–20. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770350041003. PMID 568461.

- Chuang, L., "Mental Disorders Secondary to General Medical Conditions", Medscape, archived from the original on October 19, 2011, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D (December 1996). "Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review". Psychiatr Serv. 47 (12): 1356–63. doi:10.1176/ps.47.12.1356. PMID 9117475.

- Kamboj MK, Tareen RS (February 2011). "Management of nonpsychiatric medical conditions presenting with psychiatric manifestations". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 58 (1): 219–41, xii. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.10.008. PMID 21281858.

- Van Heeringen, Kees; Audenaert, Kurt; Bernagie, Katrien; Vervaet, Myriam; Jacobs, Filip; Otte, Andreas; Dierckx, Rudi (2004). "Functional Brain Imaging of Suicidal Behaviour". Nuclear Medicine in Psychiatry. pp. 475–484. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-18773-5_28. ISBN 978-3-642-62287-8.

- Patricia D. Barry, Suzette Farmer; Mental health & mental illness, p. 282, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;(2002) ISBN 0-7817-3138-0

- Bohnert, Amy S.B.; Ilgen, Ph.D, Mark A. (2019). "Understanding Links among Opioid Use, Overdose, and Suicide". The New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1802148. PMID 30601750.

- "GHO | By category | Suicide rate estimates, age-standardized - Estimates by country". WHO. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- Smith, John C.; Hogan, Brian; Ormerod, David C.; Ormerod, David (2011). Smith & Hogan's criminal law (13th ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-19-958649-3.

- "GamerGate Leads to Suicide Prevention Charity - The Escapist". www.escapistmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2017-10-14. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- Bertolote, 2004

- Bertolote, Jose (October 2004). "Suicide Prevention: at what level does it work?". World Psychiatry. 3 (3): 147–151. PMC 1414695. PMID 16633479.

- Best Practices Registry (BPR) For Suicide Prevention Archived 2011-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Rodgers PL, Sudak HS, Silverman MM, Litts DA (April 2007). "Evidence-based practices project for suicide prevention". Suicide Life Threat Behav. 37 (2): 154–64. doi:10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.154. PMID 17521269.

- "Costs of Suicide". www.sprc.org. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

Further reading

- Pappas, Stephanie (25 Aug 2021). "New research in suicide prevention". American Psychological Association

- Suicide prevention and assessment handbook, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2011.

- Nancy Boyd-Franklin; Elizabeth N. Cleek; Matt Wofsy; Brian Mundy (2013). "Risk Assessment and Suicide Prevention". Therapy in the Real World: Effective Treatments for Challenging Problems. Guilford Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-4625-1034-4.

- Van Orden, Kimberly A.; Witte, Tracy K.; Cukrowicz, Kelly C.; Braithwaite, Scott R.; Selby, Edward A.; Joiner, Thomas E. (2010). "The interpersonal theory of suicide". Psychological Review. 117 (2): 575–600. doi:10.1037/a0018697. PMC 3130348. PMID 20438238.

External links

- CDC website on Suicide Prevention

- The Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) provides prevention support, training, and resources to assist organizations and individuals to develop suicide prevention programs, interventions and policies, and to advance the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.

- Centre for Suicide Prevention (CSP), Canada

- Suicide Prevention:Effectiveness and Evaluation A 32-page guide from SPAN USA, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, and Education Development Center, Inc.

- International Association for Suicide Prevention Organization co-sponsors World Suicide Prevention Day on September 10 every year with the World Health Organization (WHO).

- U.S. Surgeon General – Suicide Prevention

- Suicide Risk Assessment Guide – VA Reference Manual

- Practice Guidelines for Suicide prevention, APA