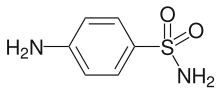

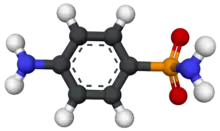

Sulfanilamide

Sulfanilamide (also spelled sulphanilamide) is a sulfonamide antibacterial drug. Chemically, it is an organic compound consisting of an aniline derivatized with a sulfonamide group.[1] Powdered sulfanilamide was used by the Allies in World War II to reduce infection rates and contributed to a dramatic reduction in mortality rates compared to previous wars.[2][3] Sulfanilamide is rarely if ever used systemically due to toxicity and because more effective sulfonamides are available for this purpose. Modern antibiotics have supplanted sulfanilamide on the battlefield; however, sulfanilamide remains in use today in the form of topical preparations, primarily for treatment of vaginal yeast infections mainly vulvovaginitis which is caused by Candida albicans.[4][5][6][7]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | salonemide Consumer Drug Information |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.513 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H8N2O2S |

| Molar mass | 172.20 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.08 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 165 °C (329 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

The term "sulfanilamides" is also sometimes used to describe a family of molecules containing these functional groups. Examples include:

Mechanism of action

As a sulfonamide antibiotic, sulfanilamide functions by competitively inhibiting (that is, by acting as a substrate analogue) enzymatic reactions involving para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA).[8][9] Specifically, it competitively inhibits the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase.[5][10] PABA is needed in enzymatic reactions that produce folic acid, which acts as a coenzyme in the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. Mammals do not synthesize their own folic acid so are unaffected by PABA inhibitors, which selectively kill bacteria.[11]

However, this effect can be reversed by adding the end products of one-carbon transfer reactions, such as thymidine, purines, methionine, and serine. PABA can also reverse the effects of sulfonamides.[5][12][11]

History

Sulfanilamide was first prepared in 1908 by the Austrian chemist Paul Josef Jakob Gelmo (1879–1961)[13][14] as part of his dissertation for a doctoral degree from the Technische Hochschule of Vienna.[15] It was patented in 1909.[16]

Gerhard Domagk, who directed the testing of the prodrug Prontosil in 1935,[17] and Jacques Tréfouël and Thérèse Tréfouël, who along with Federico Nitti and Daniel Bovet in the laboratory of Ernest Fourneau at the Pasteur Institute, determined sulfanilamide as the active form,[18] are generally credited with the discovery of sulfanilamide as a chemotherapeutic agent. Domagk was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work.[19]

In 1937, Elixir sulfanilamide, a medicine consisting of sulfanilamide dissolved in diethylene glycol, poisoned and killed more than 100 people as a result of acute kidney failure, prompting new US regulations for drug testing. In 1938, the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act was passed. It was only the solvent and not the sulfanilamide that was the problem, as sulfanilamide was widely and safely used at the time in both tablet and powder form.[20]

Chemical and physical properties

Sulfanilamide is a yellowish-white or white crystal or fine powder. It has a density of 1.08 g/cm3 and a melting point of 164.5-166.5 °C. The pH of a 0.5% aqueous solution of Sulfanilamide is 5.8 to 6.1. It has a λmax of 255 and 312 nm.[5]

Solubility: One gram of sulphanilamide dissolves in approximately 37 ml alcohol or in 5 ml acetone. It is practically insoluble in chloroform, ether, or benzene.[5]

Contraindications

Sulphanilamide is contraindicated in those known to be hypersensitive to sulfonamides, in nursing mothers, during pregnancy near term and in infants less than 2 months of age.[5]

Adverse effects

Since sulfanilamide is used almost exclusively in topical vaginal preparations these days, adverse effects are typically limited to hypersensitivity or local skin reactions. If absorbed, systemic side effects commonly seen with sulfanilamides may occur.[5]

Pharmacokinetics

A small amount of sulfanilamide is absorbed following topical application or when administered as a vaginal cream or suppository (through the vaginal mucosa). It is metabolized by acetylation like other sulfonamides and excreted through the urine.[5]

See also

External links

- Sulfanilamides at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

References

- Actor P, Chow AW, Dutko FJ, McKinlay MA. "Chemotherapeutics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_173.

- Steinert D (2000). "The Use of Sulfanilamide in World War II". The History of WWII Medicine. Archived from the original on 2016-06-07.

- "Class 9 Items: Drugs, Chemicals and Biological Stains Sulfa Drugs". Library of Congress Web Archives. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

- "Sulfanilamide". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Scholar E (2007-01-01). "Sulfanilamide". In Enna SJ, Bylund DB (eds.). xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference. New York: Elsevier. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1016/b978-008055232-3.62694-7. ISBN 978-0-08-055232-3. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- "US FDA Label: AVC (sulfanilamide) Vaginal Cream 15%" (PDF). United States Food & Drug Administration. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- Castelli LA, Nguyen NP, Macreadie IG (May 2001). "Sulfa drug screening in yeast: fifteen sulfa drugs compete with p-aminobenzoate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 199 (2): 181–4. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10671.x. PMID 11377864.

- Kent M (2000). Advanced Biology. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-914195-1.

- Sharma S (January 1997). "Chapter 18 - Antifolates". In Sharma S, Anand N (eds.). Pharmacochemistry Library. Approaches to Design and Synthesis of Antiparasitic Drugs. Vol. 25. Elsevier. pp. 439–454. doi:10.1016/s0165-7208(97)80040-2. ISBN 9780444894762.

- Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann BC (2018). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (13th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-259-58473-2. OCLC 993810322.

- Wormser GP, Chambers HF (2001-02-01). "The Antimicrobial Drugs, Second Edition by Eric Scholar and William Pratt New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. 607 pp., illustrated. $98.50 (cloth); $69.50 (paper)". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 32 (3): 521. doi:10.1086/318515. ISSN 1058-4838.

- Gelmo P (1908). "Über Sulfamide der p-Amidobenzolsulfonsäure". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 77 (1): 369–382. doi:10.1002/prac.19080770129. ISSN 1521-3897.

- "Paul Gelmo". Encyclopedia.com.

- Gelmo P (14 May 1908). "Über Sulfamide der p-Amidobenzolsulfonsäure". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 77: 369–382. doi:10.1002/prac.19080770129.

- On May 18, 1909, Deutsches Reich Patentschrift number 226,239 for sulfanilamide was awarded to Heinrich Hörlein of the Bayer corporation.

- Domagk G (February 15, 1935). "Ein Beitrag zur Chemotherapie der bakteriellen Infektionen". Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 61 (7): 250. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1129486.

- Tréfouël J, Tréfouël T, Nitti F, Bovet D (November 23, 1935). "Activité du p-aminophénylsulfamide sur l'infection streptococcique expérimentale de la souris et du lapin". C. R. Soc. Biol. 120: 756.

- Bovet D (1988). "Les étapes de la découverte de la sulfamidochrysoïdine dans les laboratoires de recherche de la firme Bayer à Wuppertal-Elberfeld (1927–1932)". Une chimie qui guérit : Histoire de la découverte des sulfamides. Médecine et Société (in French). Paris: Payot. p. 307.

- Ballentine C. "Sulfanilamide Disaster" (PDF). fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 5 May 2022.