Suomen Joutsen

Suomen Joutsen is a steel-hulled full-rigged ship with three square rigged masts. Built in 1902 by Chantiers de Penhoët in St. Nazaire, France, as Laënnec, the ship served two French owners before she was sold to German interest in 1922 and renamed Oldenburg. In 1930, she was acquired by the Government of Finland, refitted to serve as a school ship for the Finnish Navy and given her current name. Suomen Joutsen made eight long international voyages before the Second World War and later served in various support and supply roles during the war. From 1961 on she served as a stationary seamen's school for the Finnish Merchant Navy. In 1991, Suomen Joutsen was donated to the city of Turku and became a museum ship moored next to Forum Marinum.

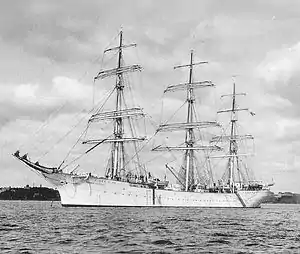

Suomen Joutsen anchored outside Helsinki in 1932. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Laënnec |

| Namesake | René Laennec |

| Owner |

|

| Port of registry | Saint-Nazaire, |

| Builder | Chantiers de Penhoët, Saint-Nazaire, France |

| Launched | 7 August 1902 |

| Maiden voyage | 23 October 1902 |

| In service | 1902–1920 |

| Fate | Sold to Germany in 1922 |

| Name | Oldenburg |

| Namesake | City of Oldenburg |

| Owner |

|

| Port of registry | Bremen, |

| In service | 1922–1930 |

| Fate | Sold to Finland in 1930 |

| Name | Suomen Joutsen |

| Namesake | Finska Svan |

| Owner |

|

| Christened | 1 November 1931 |

| Identification |

|

| Nickname(s) | "Ankka" (The Duck) |

| Status | Museum ship in Turku, Finland |

| General characteristics (as built)[1] | |

| Type | Full-rigged ship |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 12.3 m (40 ft 4 in) |

| Height | 52 m (170 ft 7 in) from waterline |

| Draft | 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in) |

| Depth | 7.29 m (23 ft 11 in) |

| Sail plan |

|

| Crew | 24–36 |

| General characteristics (as school ship)[1][2] | |

| Displacement | 2,900 tons |

| Draft | 5.15 m (16 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power | Two Skandia hot bulb engines (2 × 150 kW (200 hp)) |

| Sail plan |

|

| Speed |

|

| Complement |

|

History

Laënnec (1902–1922)

In 1902, the French shipping company Société Anonyme des Armateurs Nantais ordered two 3,100-ton full-rigged ships from Chantiers de Penhoët in Saint-Nazaire. The first ship, launched on 7 August 1902, was christened Laënnec after René Laennec, a French doctor and inventor of the stethoscope. On 18 September 1902 she was followed by the second ship, named Haudaudine after Pierre Haudaudine, which was lost off the coast of New Caledonia on 3 January 1905.[4] On 23 October 1902 Laënnec left Saint-Nazaire and headed to Cardiff, England, to load coal bound for Iquique, Chile.[1][5]

Laënnec was almost sunk on her maiden voyage when she collided with an English steam ship Penzance in the Bay of Biscay, sinking the fully laden steamer within minutes. Laënnec, also seriously damaged, was towed to Barry for repairs. One of the reasons for the incident was that she was not carrying enough sailing ballast on her voyage from the shipyard, and as a result her rudder was not completely submerged in water, significantly reducing the maneuverability of the ship. Towards the end of the nine-month voyage, while carrying potassium nitrate from Chile to Bremerhaven, Germany, a minor mutiny broke out when four crew members disobeyed orders from Captain Turbé.[1]

In 1906[note 1] Laënnec was sold to a French shipping company Compagnie Plisson. She made several voyages across the Atlantic Ocean and around Kap Horn to the Pacific Ocean, and around the Cape of Good Hope to Australia under the command of Captain Achille Guriec. On her way back to Europe she carried wheat or potassium nitrate.[1]

On 12 December 1911, while unloading potassium nitrate at the port of Santander, Spain, Laënnec was severely damaged when a storm pushed her against the pier and ripped the ship from her moorings, causing the full-rigged ship to drift against a Dutch steam ship Rhehania. As there was no shipyard large enough to accommodate Laënnec in Santander, the ship was emptied and inclined until her damaged hull plating was exposed and could be repaired within the harbour. The repairs took 20 days and the ship, which by that time had become a popular attraction for the local people, left Spain on 1 February 1912.[1] In 1914 the main mast of Laënnec broke off and fell over the starboard side when the ship was struck by a heavy storm in the North Atlantic Ocean. She was towed to Brest for repairs.[5] On 12 June 1916 Captain Guriec died onboard Laënnec while the ship was passing the Cape of Good Hope on her way back to Europe. The command was assumed by the first mate who, according to some sources, also perished before the ship arrived in England. Later the command was given to Captain Émile Delanoë.[1]

When the First World War broke out, Laënnec was equipped with two deck guns. Due to the presence of German U-boats in Europe, the ship spent the war years trading in the United States East Coast. After the war, she arrived back to her home port, Saint-Nazaire, after a 150-day voyage from Australia to be stripped and laid up. On 1 December 1920 Laënnec was put for sale.[1]

Oldenburg (1922–1930)

In late November 1922, after having been laid up for two years, Laënnec was sold to a German shipping company H. H. Schmidt & Co. from Hamburg. After refitting she was renamed Oldenburg after the city of Oldenburg and, through an agreement with the German school ship association Deutscher Schulschiffverein, she became a school ship for the German merchant navy.[6] Among the men who received their training onboard Oldenburg over the years was the German U-boat ace Günther Prien.

In 1925, while rounding Kap Horn, Oldenburg lost her main mast in a storm and had to seek shelter due to damaged rigging. After emergency repairs in Montevideo, Uruguay, she crossed the Atlantic and headed back to Hamburg. However, due to strong easterly winds she was forced to pass the British Isles on the northern side instead of the English Channel. 78 days after leaving the Río de la Plata estuary, Oldenburg was taken into tow by a German tugboat and towed to Hamburg.[6]

In 1928 Oldenburg was sold to another German shipping company, Seefart Segelschiffs-Reederei GmbH from Bremen. In 1930, on her last voyage under the German flag, Oldenburg was almost lost when the cargo of phosphate shifted in heavy weather. After two weeks in a heavy storm, the longitudinal bulkhead gave way and the ship assumed a list of 55 degrees. Lifeboats, spare yards and the kitchen stove were lost overboard. However, the crew managed to righten the ship and sail her to Malmö, Sweden. After unloading the ship was moved to Bremerhaven to be laid up.[6]

Acquisition and refitting

Although the school ship was left out from the Finnish Naval Act of 1927, the Finnish Navy decided to keep looking for a suitable vessel and purchase it separately from the major fleet renewal program. Over the years, opinions both in favor and against a school ship had been presented, but it was generally agreed that such vessel would be in many ways beneficial for the Finnish Navy. Initially there was also disagreement about the type of the ship — some were in favor of a modern steam ship that could be used in the local waters while the others preferred a traditional sailing ship that would teach the cadets traditional seaman skills and bring them closer to merchant mariners. The latter was also recommended by foreign naval officials, and finally the Finnish Navy agreed on a sailing ship. This was further helped by the Wall Street Crash of 1929 that had brought the prices down, and the fact that windjammers had been largely replaced by steam ships.[7]

In April 1930, the Parliament of Finland allotted 4,000,000 Finnish markkas for procuring a second-hand full-rigged ship and refitting it as a school ship for the Finnish Navy. During the summer of 1930, the Finnish officials inspected a number of Finnish and foreign ships that were offered for sale. These included Gustav Erikson's four-masted barques Pommern and Herzogin Cecilie, and several other ships, but all were deemed either too large or too dilapidated. In the end, the most suitable candidate came from Germany where Oldenburg, a 28-year-old former school ship of the German merchant navy, was offered for sale.[7] After inspecting the ship in Bremen, the Finnish officials purchased her in August 1930 and the German crew sailed the ship to Helsinki.[5][8]

After having been handed over to the Finnish Navy, Oldenburg was towed to Uusikaupunki for refitting. The work, which began in late 1930 and continued until November 1931, included replacing part of the bottom plating, building an additional tweendeck, refurbishing the rigging, painting the whole ship and rebuilding her cargo holds to accommodate up to 180 men. The shipyard was responsible for the structural alterations while 62 future crew members and cadets of the Finnish Navy were responsible for the other tasks, including carrying 1,200 tons of stones to the ship as sailing ballast.[2]

On 1 November 1931, after a number of delays, Oldenburg was renamed Suomen Joutsen (Swan of Finland) after Finska Svan, a Swedish 16th century warship that took part in the naval action of 7 July 1565 between Sweden and Denmark. After launching, Suomen Joutsen broke her moorings in the strong breeze and damaged two ships, gunboat Karjala and Osmo, a laid-up full-rigged ship built in 1869, before she was brought under control. On 4 November 1931, she left the shipyard for Helsinki, under tow and escorted by minelayer M-1.[9]

School ship (1931–1939)

Due to delays during the refitting and later problems with the steam heating system, the first voyage of Suomen Joutsen was delayed until late December. Captain Arvo Lieto proposed postponing the departure until the next autumn as Christmas was drawing near and the sea was already freezing, but on 21 December 1931 President P. E. Svinhufvud ordered the ship to begin her first international school sailing under the Finnish flag. Suomen Joutsen was towed to the sea on the following day, but she had to wait for favourable winds outside Porkkala until 28 December, at which point she had already been grounded once. The streak of bad luck continued when the ship was anchored in Trongisvágsfjørður in Suðuroy, Faroe Islands, after stopping to purchase more lubrication oil at Trongisvágur. Suomen Joutsen dragged her anchors in a storm measuring 11–12 on the Beaufort scale, drifting stern first towards the shore. After two trawlers and a tugboat managed to get the full-rigged ship safely to the harbour, it was found out that the rudder had been damaged and the ship was towed to England for drydocking. After repairs, Suomen Joutsen continued to the Canary Islands, where she remained for three weeks while Captain Lieto was relieved of command and replaced by John Konkola, who served as the captain of the school ship for six full and two partial voyages. From the Canary Islands, Suomen Joutsen headed south, but the refrigeration system failed 500 kilometres (310 mi) before the Equator and she had to turn back before a line-crossing ceremony could be held. However, the crew got some consolation when news about the end of prohibition in Finland reached the ship while she was sailing towards Finland in the Baltic Sea. Suomen Joutsen arrived in Finland on 22 May 1932 and was drydocked at Suomenlinna shortly thereafter.[10]

The second voyage of Suomen Joutsen began on 18 October 1932, and after stopping briefly in the Canady Islands and Cape Verde, she crossed the Equator on 11 December for the first time flying the Finnish flag. On 24 December, the crew celebrated traditional Finnish Christmas outside Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and arrived at the port on the following morning. The visit of "Cisne Blanco de Finlandia", the white swan of Finland, was widely covered in local newspapers. From Rio de Janeiro, Suomen Joutsen continued her voyage to Montevideo, Uruguay, and then, against her original sailing plan, to Buenos Aires. After leaving Argentine and visiting a number of ports in the Caribbean, Suomen Joutsen crossed the Atlantic and finally arrived in Finland on 3 May 1933. On the way back, her crew caught a number of sea turtles for the Helsinki Zoo.[11]

On her third international sailing, Suomen Joutsen left Helsinki on 1 November 1933 and headed to the Mediterranean, where she visited the ports of Marseille, Alexandria and Naples. While heading towards Gibraltar on her way to the Atlantic, an English steam ship tauntingly offered to tow the Finnish full-rigged ship which was sailing slowly close to the wind. However, shortly afterwards the wind changed its direction and Suomen Joutsen overtook the steamer with a towing line hanging from the stern hawsehole, offering to provide assistance for the slower ship. After stopping briefly at the Canary Islands, the ship crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Haiti on 10 March 1934 after 25 days of sailing. The return voyage began six days later. On 6 April, while in the middle of the Northern Atlantic, Suomen Joutsen was hit by hurricane-force winds that caused the ship to list almost 56 degrees. She survived the worst storm of her career without major damage and arrived in Helsinki on 16 May 1934.[12]

Suomen Joutsen began her fourth voyage on 30 October 1934 and arrived at her first stop, Cartagena in Spain, in late November. While sailing towards the Greek port city of Piraeus outside Sardinia on 7 December, she was overtaken by the Italian 51,000-ton ocean liner SS Rex which passed Suomen Joutsen at full speed of 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) from a distance of only 50 metres (55 yards). Although the holder of the Blue Riband was a sight to behold, seeing a full-rigged ship underway in the open seas was also becoming a rare treat. After visiting various ports in the Mediterranean, the ship returned to the Atlantic and stopped briefly at Ponta Delgada, but crossed neither the Atlantic nor the Equator. Suomen Joutsen returned to Helsinki on 3 May 1935.[13][14]

The fifth voyage of Suomen Joutsen was the longest the ship had ever done under the Finnish flag. After leaving Helsinki on 9 October 1935, the ship stopped briefly at Lisbon, Portugal, and then continued across the Atlantic, eventually arriving in the Panama canal on 26 December. It took eleven and a half hours to transit the 81-kilometre (50 mi) canal. After leaving Panama behind, Suomen Joutsen headed south and crossed the Equator on 4 January 1936 with appropriate ceremonies. Later the ship stopped at Callao in Peru and Valparaiso in Chile, where five men escaped after a local barkeeper had offered them full upkeep for playing at his bar. The men were later caught by local officials and returned to Finland, where they were sentenced for six months in prison. After leaving Chile, Suomen Joutsen sailed around the Cape Horn without major difficulties and arrived in Buenos Aires on 21 March. From Argentine, the ship continued to Rio de Janeiro, where she encountered the Brazilian school ship Almirante Saldanha, whose purchase had been inspired by the previous visit of the white swan of Finland. Suomen Joutsen sailed out on 14 April and due to heavy weather and headwinds, it took seven weeks to reach the Azores. On 9 May, Captain Konkola turned 50 and after the crew had sung "Happy Birthday to You" at 6:30 in the morning, he stuck his head out from the cabin door and yelled "Steward, give them booze!" Suomen Joutsen arrived in Helsinki on 4 July 1936. After a number of disagreements regarding the use of tugboats in the foreign ports, Captain Konkola decided to sail the full-rigged ship all the way to the harbour, crossing the narrow Kustaanmiekka strait at full sail. Finally, when the bow had already been moored at Katajanokka, he allowed the tugboat to push the stern against the pier and the fifth voyage was over.[15]

On her sixth voyage, the most important stop of Suomen Joutsen was New York City, where the ship arrived on 3 March 1937. Prior to this, the ship had visited Portugal, Senegal and a number of ports in the Caribbean after leaving Helsinki on 2 November 1936. However, the ship's first and only visit to the United States under the Finnish flag was an important milestone and a major media event. When the ship was sailing up the Hudson River, an American film crew came on board to capture her arrival, and Suomen Joutsen remained the center of attention for the six days she was moored at the western end of the 35th Street. When the ship left New York, a member of the crew was accidentally left on the shore. However, he managed to talk a local tugboat captain to take him back to the school ship and, for solving the problem on his own initiative, was left without punishment. After stopping at Oslo, Suomen Joutsen arrived in Helsinki on the May Day of 1936. Among the first people to leave the ship was a man carrying a living crocodile under his arm, captured for the Helsinki Zoo.[16]

The seventh voyage of Suomen Joutsen began on 20 October 1937 and took the ship first across the Atlantic to South America. After calling Montevideo, she continued east to Cape Town, stopping at Tristan da Cunha along the way. The seventh voyage has often been called the unluckiest one as three crew members were lost before the ship arrived back in Finland on 12 May 1938. On 7 February, a seaman fell from the bow mast and was buried at sea on the following day. On the way to Cape Town, a sergeant became ill and later died in a hospital in South Africa on 10 March. On 10 May, a member of the regular crew fell to the sea while painting the hull when the ship was underway in the Baltic Sea. Many thought that the deaths were due to the crew killing three albatrosses earlier in the voyage. Finally, when Suomen Joutsen was outside Helsinki, a small airplane flew too close to the ship and crashed into the sea, but the pilots were rescued.[17][18]

Suomen Joutsen left for her eighth and last international voyage on 27 October 1938. After stopping at Copenhagen for provisions and clearing the English Channel — and almost colliding with the Polish passenger ship Piłsudski — she continued to the Bay of Biscay. However, 15-metre (49 ft) waves forced Suomen Joutsen to turn back on 23 November and head to Bordeaux to wait for the weather to clear. Captain Konkola, concerned about his ailing health, was relieved of his duty and replaced by Unto Voionmaa on 3 December 1938. Under his command, Suomen Joutsen crossed the Atlantic twice, calling the ports of Pernambuco in Brazil and San Juan in Puerto Rico. On her last stop at Rotterdam, there were already signs of a major conflict in the air, and had the war started before the ship arrived in Finland, she would have headed to the United Kingdom. Suomen Joutsen arrived in Helsinki on 22 April 1939, after which she never left the Baltic Sea again.[19]

Second World War (1939–1945)

During the summer of 1939, the rigging of Suomen Joutsen was partially dismantled and her hull was painted dark grey. She was used as a supply ship for the Finnish submarine fleet within the Finnish archipelago. When the Winter War broke out on 30 November 1939, she was stationed in Högsåra with the submarines and coastal defence ships Väinämöinen and Ilmarinen. After three Soviet scout planes flew over the ships, the fleet moved hastily to another safe location near Nagu only hours before eight four-engined enemy bombers overflew the previous anchorage. During the first weeks of the war, Suomen Joutsen was assigned to "moving supply depot" under the Archipelago Sea Fleet that consisted of the full-rigged ship and a number of barges and tugboats. She served in this task until the Winter War ended with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940. During the Interim Peace she was stationed in Naantali.[20]

When the Continuation War started on 25 June 1941, Suomen Joutsen resumed her old tasks as a moving supply depot under the Archipelago Sea Fleet. Since the Finnish Navy now had a dedicated submarine tender, icebreaker Sisu, the former school ship was relegated to supply motor torpedo boats. After the war ended on 19 September 1944, Suomen Joutsen was used as an accommodation ship in Turku.[20]

During the war, around 150 men were stationed on Suomen Joutsen. The ship was lightly armed with only two machine guns and around 40 rifles.[20] She survived the war largely intact, with only minor shrapnel damage from Soviet air raids.[21]

After the war (1945–1961)

After the war, Suomen Joutsen participated in the demining of the Finnish coastal waters, for which purpose she was fitted with an engine repair shop and a sauna for the crews of the minesweepers. She served in this task until the mine clearance was finished in 1948, but was afterwards used as an accommodation and supply ship for different branches of the Finnish Navy. In 1955–1959 she was stationed in Upinniemi.[20]

While Suomen Joutsen served as a supply ship for the minesweeping fleet, her crew rebuilt the rigging dismantled before the war and the school ship spent a couple of days sailing in the Baltic Sea in late 1948. Although there were plans to reactivate her as a school ship for either the Finnish Navy or the Finnish Merchant Fleet, or both, there were issues with her naval ensign — as a naval school ship she would not be allowed to carry cargo or be crewed by civilians, but a civilian flag would force her to pay expensive harbour fees. There was also no longer need for a civilian full-rigged school ship. In 1949–1951, Suomen Joutsen conducted a number of short training and promotional sailings in the Baltic Sea, but never ventured further than the southern tip of Gotland.[20][22]

Although everything was ready for the first post-war school sailing, President J. K. Paasikivi was against the voyage — sailing a full-rigged ship so soon after the war while the Finnish war reparations to the Soviet Union were still being paid was deemed too flamboyant. It was Paasikivi who, as the director of the Finnish Export Society in the 1930s, had been one of the major supporters of Suomen Joutsen. The danger of stray naval mines had also not completely disappeared.[20][22] In 1961, the Finnish Navy purchased HMS Porlock Bay, a Bay class frigate, as the new school ship.[23]

Seamen's school (1961–1991)

In the late 1940s, the Finnish Seamen's Union proposed the Finnish government that Suomen Joutsen should be turned into a stationary seamen's school. As nothing happened, the Union renewed its proposal with a different tone in the late 1950s when it learned that the government was planning to sell the old full-rigged ship for German scrap dealers and, in fact, the first payment had already been made. The Union gave its ultimatum on 29 April 1959 and when the government did not react, the crews of the inspection ships under the Finnish Maritime Administration went on a strike on 2 May. Before the action could spread, the government acceded and it was agreed that Suomen Joutsen would be stationed in Turku. However, due to intentional delays nothing happened until Niilo Wälläri, the leader of the Finnish Seamen's Union, presented his final ultimatum on 13 January 1960: if the preparations to turn Suomen Joutsen into a seamen's school did not begin immediately, the Finnish state-owned icebreakers would go into strike on 15 January, effectively stopping all foreign trade. Two days later, icebreaker Sampo began towing the former school ship through the icefields towards Turku, where the convoy arrived on 17 January 1960.[24] This was also one of the last missions of the old steam-powered icebreaker before she was decommissioned and sold for scrap.[25]

Suomen Joutsen was rebuilt again in 1960–1961 and most of her interior was converted into classrooms, workshops and student accommodation — only the captain's salon remained in its original shape. Two new classrooms were also built on the deck, slightly altering the appearance of the vessel. The first classes were held on 1 March 1961, and on 4 May the school was officially opened. On the same day, the naval ensign was replaced with the civilian flag.[26]

Suomen Joutsen served as a seamen's school for 27 years, during which time 3,709 students received their basic training on board the full-rigged ship. In the 1980s, the facilities on board the school ship were becoming too small and increasingly obsolete, and there were talks about closing the school by the end of the decade. There was also discussion about turning Suomen Joutsen to a museum ship. The school closed its doors in 1988 and three years later Suomen Joutsen was handed over to the city of Turku.[27]

Museum ship (1991–)

Suomen Joutsen has been open to the public since 1991. She is one of the largest museum ships in Finland, slightly shorter but bigger by gross register tonnage than the four-masted barque Pommern in Mariehamn, Åland, and considerably bigger than the wooden barque Sigyn which is moored next to her. Suomen Joutsen was moved from her original location next to Forum Marinum in 2002. Her extensive renovations since the late 1990s included drydockings in 1998 and 2006.[28] Since 2009 she has hosted a permanent exhibition about her career.

On 25 July 2001, Suomen Joutsen received minor damage when the 1938-built steamer Ukkopekka collided with the museum ship. However, the damaged shell plating and frame were above the waterline, so the ship was in no danger of sinking.[29]

In 2006 Pekka Koskenkylä, the founder of Nautor, revealed that the Swan line of luxury sailing yachts was named after Suomen Joutsen.[30]

In September 2016, Suomen Joutsen was towed to Turku Repair Yard for drydocking. After inspection and maintenance of the underwater parts, which is typically done once in a decade, the museum ship should be good for another ten years.[31] The ship returned to Forum Marinum in late October.

International voyages under the Finnish flag

During her time as the school ship of the Finnish Navy, Suomen Joutsen carried out eight long sailing voyages in 1931–1939. Although her rigging was refitted for sailing after the Second World War, she was only used for short voyages in the Baltic Sea until her retirement.[3]

- First voyage (22 December 1931 – 22 May 1932)

- Helsinki, Finland - Copenhagen, Denmark - Faroe Islands - Hull, England - Las Palmas, Canary Islands - 5.5° N - Ponta Delgada, Azores - Vigo, Spain - Helsinki, Finland

- Second voyage (20 October 1932 – 3 June 1933)

- Helsinki - Las Palmas, Canary Islands - Rio de Janeiro, Brazil - Montevideo, Uruguay - Buenos Aires, Argentine - Saint Lucia - Saint Thomas, United States Virgin Islands - Ponta Delgada, Azores - Helsinki, Finland

- Third voyage (1 November 1933 – 15 May 1934)

- Helsinki, Finland - Marseille, France - Alexandria, Egypt - Naples, Italy - Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands - Port-au-Prince, Haiti - Lisbon, Portugal - Helsinki, Finland

- Fourth voyage (31 October 1934 – 3 May 1935)

- Helsinki, Finland - Cartagena, Spain - Piraeus, Greece - Saloniki, Greece - Beirut, Lebanon - Haifa, Israel - Alexandria, Egypt - Casablanca, Morocco - Ponta Delgada, Azores - Gravesend, England - Helsinki, Finland

- Fifth voyage (9 October 1935 – 2 July 1936)

- Helsinki, Finland - Lisbon, Portugal - La Guaira, Venezuela - Cartagena, Colombia - Colón, Panama - Balboa, Panama - Callao, Peru - Valparaiso, Chile - around the Cape Horn - Buenos Aires, Argentine - Rio de Janeiro, Brazil - Ponta Delgada, Azores - Helsinki, Finland

- Sixth voyage (2 November 1936 – 1 May 1937)

- Helsinki, Finland - Oporto, Portugal - Dakar, Senegal - Ciudad Trujillo, Dominican Republic - Vera Cruz, Mexico - Havana, Cuba - New York City, United States - Oslo, Norway - Helsinki, Finland

- Seventh voyage (10 October 1937 – 12 May 1938)

- Helsinki, Finland - Funchal, Madeira - Montevideo, Uruguay - Tristan da Cunha - Cape Town, South Africa - Calais, France - Helsinki, Finland

- Eighth voyage (27 October 1938 – 23 April 1939)

- Helsinki, Finland - Bordeaux, France - Casablanca, Morocco - Recife, Brazil - San Juan, Puerto Rico - Ponta Delgada, Azores - Rotterdam, Netherlands - Helsinki, Finland

An exhibition prepared by the Finnish Export Society was carried on three voyages.

General characteristics

Suomen Joutsen is a steel-hulled full-rigged ship with three square rigged steel masts. Both main mast and bow mast have six yards, the longest ones being 27 metres (88 ft 7 in) long and weighing four tons, while the mizzenmast has five yards. The height of her main mast, which consists of three parts, is 52 metres (170 ft 7 in) from the waterline. The sail area of Suomen Joutsen is 2,200 square metres (24,000 sq ft)[note 3] and three sets of sails, each weighing three tons, were carried on training voyages. Her standing and running rigging consist of over 30 kilometres (19 mi) of manilla ropes and steel cables. The typical sailing speed of Suomen Joutsen was around 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), but once in the North Sea she reached a record speed of 16.4 knots (30.4 km/h; 18.9 mph) with only topsails and the foresail.[1][2]

The overall length of Suomen Joutsen is 96 metres (315 ft 0 in). Her hull is 80 metres (262 ft 6 in) long at the waterline, has a beam of 12.3 metres (40 ft 4 in) at midship and depth of 7.29 metres (23 ft 11 in) to main deck. When she was carrying cargo, her tonnage was 2,393 register tons gross, 1,734 register tons net and 3,100 tons deadweight.[note 2] The ship drew 6.35 metres (20 ft 10 in) of water when loaded, but as a school ship she sailed with a ballast draft of only 5.15 metres (16 ft 11 in). With 1,200 tons of stones as sailing ballast, her displacement was 2,900 tons and metacentric height 0.699 metres (2 ft 3.5 in). Later some of the stone ballast was replaced with concrete and iron.[32] Internally her hull was divided into five watertight compartments.[1][2]

When Suomen Joutsen was converted to a school ship for the Finnish Navy, her general arrangements were changed considerably in order to accommodate up to 180 men on long international voyages. In addition to living quarters, bathrooms and toilets, this included building kitchens and six refrigerated rooms for provisions, workshops for a carpenter, shoemaker and tailor, laundry room, hospital with ten beds and a small isolation ward, classroom, library, canteen, and more storage space for sails, ropes, paint, sand and coal. Nine freshwater tanks with a total capacity of 206 tons were also built, but in order to conserve water a traditional Finnish sauna was not provided. Instead, hot steam could be diverted into the washing rooms under the forecastle.[2]

Originally built without auxiliary propulsion, Suomen Joutsen was refitted with two Skandia hot bulb engines, each producing 200 hp, coupled to three-bladed fixed pitch propellers. The twin-shaft propulsion arrangement was very uncommon at that time. In practice the engines were found out to be underpowered, but they could still be used to assist manoeuvering in ports and in heavy weather. Two generators (5 kW and 8 kW) were added to produce electricity for about three hundred lights. While Suomen Joutsen had a steam boiler for central heating, she did not have steam winches — anchors and yards were lifted using a manual capstan.[2]

Notes

- 1920 according to some sources.

- For Haudaudine. (Wreck of a French Ship. Grey River Argus, 24 February 1905)

- 2,807 m2 (30,210 sq ft) according to original drawings (Auvinen (2002)), but otherwise always reported as 2,200 m2 (24,000 sq ft) in sources.

References

- Auvinen (2002), pages 9–14.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 12–14.

- Auvinen (1983).

- Shipwreck. Colonist, 5 January 1905. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 10–11.

- Auvinen (2002), pages 15–17.

- Aalste et al. (1989), page 9.

- Auvinen (2002), pages 18–19.

- Aalste et al. (1989), page 18.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 27–33.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 34–37

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 38–46

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 47–51.

- Auvinen (2002), page 101.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pp. 55–65.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pp. 66–76.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 77–83

- Auvinen (2002), pp. 221–223.

- Aalste et al. (1989), pages 84–90.

- Auvinen (2002), pp. 273–276.

- Aalste et al. (1989), p. 91.

- Aalste et al. (1989), p. 93–94.

- Auvinen (2002), pp. 277–278.

- Aalste et al. (1989), p. 95–96.

- Laurell, Seppo (1992). Höyrymurtajien aika. Jyväskylä: Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. pp. 330–335. ISBN 951-47-6775-6.

- Aalste et al. (1989), p. 99–103.

- Auvinen (2002), p. 278.

- Suomen Joutsen telakalle. Turun Sanomat, 6 January 2006. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- Forum Marinum -säätiön ilmoitus museoalus Suomen Joutsenen vaurioitumisesta Archived 2005-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. Turun Kaupunki, 6 August 2001. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- Suomen Joutsen paljastui Swanien esikuvaksi Archived 2014-07-28 at the Wayback Machine. Turun Sanomat, 30 July 2006. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- Suomen Joutsen lähti määräaikaishuoltoon – videolla museolaivan ensimmäinen matka vuosikymmeneen. Helsingin Sanomat, 20 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- Juutilainen (1942).

Bibliography

- Auvinen, Visa (1983). Leijonalippu merellä. Pori: Satakunnan Kirjateollisuus Oy. ISBN 951-95781-1-0.

- Auvinen, Visa (2002). Suomen Joutsen – Onnekas satavuotias. TS-Yhtymä Oy. ISBN 951-9129-48-0.

- Aalste, Juhani; Aittola, Heikki; Mauno, Jukka (1989). Suomen Joutsen. Merikustannus Oy. ISBN 951-95457-2-7.

- Juutilainen, Martti (1942). Sellainen oli retkemme – Suomen Joutsenen matkat maailman merillä. Fennia.