Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also used by the Royal Air Force (RAF), as well as several overseas operators, including the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and the Royal Netherlands Navy. It was initially operated primarily as a fleet attack aircraft. During its later years, the Swordfish was increasingly used as an anti-submarine and training platform. The type was in frontline service throughout the Second World War.

| Swordfish | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Swordfish LS 326 in flight in 2013 | |

| Role | Torpedo bomber |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Fairey |

| Built by | Fairey, Blackburn Aircraft |

| First flight | 17 April 1934 |

| Introduction | 1936 |

| Retired | 21 May 1945 |

| Primary users | Fleet Air Arm, Royal Navy |

| Produced | 1936–1944 |

| Number built | 2,391 (692 by Fairey and 1,699 by Blackburn) |

Despite being a representation of early 1930s aircraft design and teetering on the edge of becoming outdated (in comparison to some alternatives), the Swordfish achieved some spectacular successes during the war. Notable events included sinking one battleship and damaging two others of the Regia Marina (the Italian navy) during the Battle of Taranto, and the famous attack on the German battleship Bismarck, which contributed to her eventual demise. Swordfish sank a greater tonnage of Axis shipping than any other Allied aircraft during the war.[1] The Swordfish remained in front-line service until V-E Day, having outlived some of the aircraft intended to replace it.

Development

Origins

In 1933 Fairey, having established a proven track record in the design and construction of naval aircraft, commenced development of an entirely new three-seat naval aircraft, intended for the twin roles of aerial reconnaissance and torpedo bomber.[1] Receiving the internal designation of T.S.R. I, standing for Torpedo-Spotter-Reconnaissance I, the proposed design adopted a biplane configuration and a single 645 hp Bristol Pegasus IIM radial engine as its powerplant. The company chose initially to pursue development of the project as a self-financed private venture while both customers and applicable requirements for the type were sought.[1] Development of the T.S.R. I was in parallel to Fairey's activities upon Air Ministry Specification S.9/30, for which the company was at one point developing a separate but broadly similar aircraft, powered by a Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine instead as well as employing a differing fin and rudder configuration.[2]

Significant contributions to the T.S.R.I's development came from Fairey's independent design work on a proposed aircraft for the Greek Naval Air Service, which had requested a replacement for their Fairey IIIF Mk.IIIB aircraft, and from specifications M.1/30 and S.9/30, which had been issued by the British Air Ministry.[3] Fairey promptly informed the Air Ministry of its work for the Greeks, whose interest had eventually waned, and proposed its solution to the requirements for a spotter-reconnaissance plane ("spotter" referring to the activity of observing and directing the fall of a warship's gunfire). In 1934, the Air Ministry issued the more advanced Specification S.15/33, which formally added the torpedo bomber role.[3]

On 21 March 1933, the prototype T.S.R. I, F1875, conducted its maiden flight from Great West Aerodrome, Heathrow, piloted by Fairey test pilot Chris Staniland.[3] F1875 performed various flights, including several while re-engined with an Armstrong Siddeley Tiger radial engine before it was refitted with the Pegasus engine again, was used to explore the flight envelope, and to investigate the aircraft's flight characteristics. On 11 September 1933, F1875 was lost during a series of spinning tests in which it became unable to recover; the pilot survived the incident.[3] Prior to this, the prototype had exhibited favourable performance, which contributed to the subsequent decision to proceed with the more advanced T.S.R II prototype, which had been specifically developed to conform with the newly issued Specification S.15/33.[3]

On 17 April 1934, the prototype T.S.R II, K4190, performed its maiden flight, flown by Staniland.[3] In comparison with the previous prototype, K4190 was equipped with a more powerful model of the Pegasus engine, an additional bay within the rear fuselage to counteract spin tendencies, and the upper wing was slightly swept back to account for the increased length of the fuselage; along with other aerodynamic-related tweaks to the rear of the aircraft. During the ensuing flight test programme, K4190 was transferred to Fairey's factory in Hamble-le-Rice, Hampshire, where it received a twin-float undercarriage in place of its original land-only counterpart; on 10 November 1934, the first flight of K4190 in this new configuration was performed.[3] Following successful water-handling trials, K4190 conducted a series of aircraft catapult and recovery tests aboard the battlecruiser HMS Repulse. K4190 was later restored to its wheeled undercarriage prior to an extensive evaluation process by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at RAF Martlesham Heath.[4]

In 1935, following the successful completion of testing at Martlesham, an initial pre-production order for three aircraft was placed by the Air Ministry; it was at this point that the T.S.R II received the name Swordfish.[5] All three pre-production aircraft were powered by the Pegasus IIIM3 engine, but adopted a three-bladed Fairey-Reed propeller in place of the two-bladed counterpart used on the earlier prototype. On 31 December 1935, the first pre-production Swordfish, K5660, made its maiden flight.[5] On 19 February 1936, the second pre-production aircraft, K5661, became the first to be delivered; the final pre-production aircraft, K5662, was completed in the floatplane configuration and underwent water-based service trials at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at Felixstowe, Suffolk.[5]

Production and further development

In early 1936, an initial production contract for 68 Swordfish aircraft was received, as the Swordfish I.[5] Manufactured at Fairey's factory in Hayes, West London, the first production aircraft was completed in early 1936 and the type entered service with the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) in July 1936.[5] By early 1940, Fairey was busy with the Swordfish and other types such as the new Fairey Albacore torpedo bomber.[6] The Admiralty approached Blackburn Aircraft with a proposal that manufacturing activity for the Swordfish be transferred to the company, who immediately set about establishing a brand new fabrication and assembly facility in Sherburn-in-Elmet, North Yorkshire.[7] Less than a year later, the first Blackburn-built Swordfish conducted its first flight. During 1941, the Sherburn factory assumed primary responsibility for the fuselage, along with final assembly and testing of finished aircraft.[8]

Efforts were made to disperse production and to employ the use of shadow factories to minimise the damage caused by Luftwaffe bombing raids.[8] Major sub-assemblies for the Swordfish were produced by four subcontractors based in neighbouring Leeds, these were transported by land to Sherburn for final assembly. Initial deliveries from Sherburn were completed to the Swordfish I standard; from 1943 onwards, the improved Swordfish II and Swordfish III marks came into production and superseded the original model.[8] The Swordfish II carried ASV Mk. II radar and featured metal undersurfaces to the lower wings to allow the carriage of 3-inch rockets, later-built models also adopted the more powerful Pegasus XXX engine. The Swordfish III was fitted with centimetric ASV Mk.XI radar between the undercarriage legs, deleting the ability to carry torpedoes and retained the Pegasus XXX powerplant.[8]

On 18 August 1944, production of the Swordfish was terminated; the last aircraft to be delivered, a Swordfish III, was delivered that day.[9] Almost 2,400 aircraft had been built, 692 having been constructed by Fairey and a further 1,699 by Blackburn at their Sherburn facility. The most numerous version of the Swordfish was the Mark II, of which 1,080 were completed.[10]

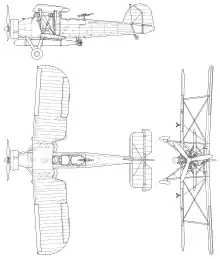

Design

The Fairey Swordfish was a medium-sized biplane torpedo bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. The Swordfish employed a metal airframe covered in fabric. It had folding wings as a space-saving measure, which was useful onboard aircraft carriers and battleships. In service, it received the nickname Stringbag; this was not due to its biplane struts, spars, and braces, but a reference to the seemingly endless variety of stores and equipment that the type was cleared to carry. Crews likened the aircraft to a housewife's string shopping bag, common at the time and which could accommodate contents of any shape, and that a Swordfish, like the shopping bag, could carry anything.[11]

The primary weapon of the Swordfish was the aerial torpedo, but the low speed of the biplane and the need for a long straight approach made it difficult to deliver against well-defended targets. Swordfish torpedo doctrine called for an approach at 5,000 feet (1,500 m) followed by a dive to torpedo release altitude of 18 feet (5.5 m).[12] Maximum range of the early Mark XII torpedo was 1,500 yards (1,400 m) at 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph) and 3,500 yards (3,200 m) at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph).[13] The torpedo travelled 200 feet (61 m) forward from release to water impact, and required another 300 yards (270 m) to stabilise at preset depth and arm itself. Ideal release distance was 1,000 yards (910 m) from target if the Swordfish survived to that distance.[12]

The Swordfish was also capable of operating as a dive-bomber. During 1939, Swordfish on board HMS Glorious participated in a series of dive-bombing trials, during which 439 practice bombs were dropped at dive angles of 60, 67 and 70 degrees, against the target ship HMS Centurion. Tests against a stationary target showed an average error of 49 yd (45 m) from a release height of 1,300 ft (400 m) and a dive angle of 70 degrees; tests against a manoeuvring target showed an average error of 44 yd (40 m) from a drop height of 1,800 ft (550 m) and a dive angle of 60 degrees.[14]

After more modern torpedo attack aircraft were developed, the Swordfish was soon redeployed successfully in an anti-submarine role, armed with depth charges or eight "60 lb" (27 kg) RP-3 rockets and flying from the smaller escort carriers, or even merchant aircraft carriers (MACs) when equipped for rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO).[15] Its low stall speed and inherently tough design made it ideal for operation from the MACs in the often severe mid-Atlantic weather. Indeed, its takeoff and landing speeds were so low that, unlike most carrier-based aircraft, it did not require the carrier to be steaming into the wind. On occasion, when the wind was right, Swordfish were flown from a carrier at anchor.[16]

Operational history

Introduction

In July 1936, the Swordfish formally entered service with the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), which was then part of the RAF; 825 Naval Air Squadron became the first squadrons to receive the type that month.[5] The Swordfish began replacing both the Fairey Seal in the spotter-reconnaissance role and the Blackburn Baffin in the torpedo bomber role in competition with the Blackburn Shark in the combined role.[5] Initially, the Shark replaced the Seal in the spotter-reconnaissance squadrons and the Swordfish replaced the Baffin in torpedo squadron, after which the Shark was quickly replaced by the Swordfish. For nearly two years during the late 1930s, the Swordfish was the sole torpedo bomber aircraft equipping the FAA.[5]

By the eve of war in September 1939, the FAA, which had been transferred to Royal Navy control, had 13 operational squadrons equipped with the Swordfish I.[5] There were also three flights of Swordfish equipped with floats, for use with catapult-equipped warships. After the outbreak of the Second World War, 26 FAA Squadrons were equipped with the Swordfish. More than 20 second-line squadrons also operated the Swordfish for training.[17] During the early months of the conflict, the Swordfish operated in mostly uneventful fleet protection and convoy escort missions.[9]

Norwegian Campaign

The Swordfish first saw combat on 11 April 1940, during the Norwegian Campaign. Several Swordfish aircraft were launched from the aircraft carrier HMS Furious to torpedo several German vessels reported to be anchoring at Trondheim. The Swordfish found only two enemy destroyers at Trondheim, scoring one hit in the first attack of the war by torpedo-carrying aircraft.[9]

On 13 April 1940, a Swordfish launched from HMS Warspite spotted fall of shot and radioed gunnery corrections back to the ship during the Second Battle of Narvik.[9] Eight German destroyers were sunk or scuttled without any British losses. The German submarine U-64 was also spotted by the Swordfish, which dive-bombed and sank the submarine. This was the first U-boat to be destroyed by an FAA aircraft in the war.[18][19][20]

After the Second Battle of Narvik, Swordfish continually bombed ships, land facilities, and parked enemy aircraft around Narvik.[21] Anti-submarine patrols and aerial reconnaissance missions were also flown despite difficult terrain and inhospitable weather, which proved especially challenging for aircrew in the Swordfish's open cockpit. For many Swordfish crews, this campaign marked their first combat missions and nighttime landings upon aircraft carriers.[21]

Mediterranean operations

On 14 June 1940, soon after the Italian declaration of war, nine Swordfish of 767 Naval Air Squadron stationed in Hyeres, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France took off for the first Allied bombing raid upon Italian soil.[22] Four days later, 767 Squadron relocated to Bone, Algeria before being split, the training elements returning to Britain while the operational portion proceeded to RAF Hal Far on Malta, where it was re-numbered as 830 Naval Air Squadron. On 30 June, operations re-commenced with an opening night raid upon oil tanks at Augusta, Sicily.[22]

On 3 July 1940, the Swordfish was one of the main weapons during the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, an attack by the Royal Navy upon the French Navy fleet stationed at Oran, French Algeria to prevent the vessels falling into German hands.[22] Twelve Swordfish from 810 and 820 Naval Air Squadrons launched from the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal and conducted three sorties of attacks upon the anchored fleet. The torpedo attack, which crippled the French battleship Dunkerque and damaged other vessels present, demonstrated that capital ships could be effectively attacked while in harbour; it was also the first time in history that the Royal Navy had won a battle without the use of gunfire.[22]

Shortly after the Mers-el-Kébir attack, a detachment of three Swordfish were sent to support British Army operations in the Western Desert, in response to a request for torpedo aircraft to destroy hostile naval units operating off the coast of Libya.[22] On 22 August, the three aircraft destroyed two U-boats, one destroyer and a replenishment ship in the Gulf of Bomba, Libya, using only three torpedoes.[23]

On 11 November 1940, Swordfish flying from HMS Illustrious achieved great success in the Battle of Taranto.[24] The main fleet of the Italian Navy was based at Taranto in southern Italy; in light of the success of the earlier attack upon the French Navy at Mers-el-Kébir, members of the Admiralty sought another victory under similar conditions. The Royal Navy had conducted extensive preparations, with some planning having taken place as early as 1938, when war between the European powers had already seemed inevitable.[24] Regular aerial reconnaissance missions were flown to gather intelligence on the positions of specific capital ships and Swordfish crews were intensively trained for night flying operations, as an undetected aerial attack during the night raid had been judged to be the only effective method of reasonably overcoming the defences of the well-protected harbour and to strike at the fleet anchored there.[24]

Originally scheduled for 21 October 1940, the Taranto raid was delayed until 11 November to allow for key reinforcements to arrive and other commitments to be met.[24] The aerial attack started with a volley of flares being dropped by Swordfish aircraft to illuminate the harbour, after which, the Swordfish formation commenced bombing and torpedo runs. Due to the presence of barrage balloons and torpedo nets restricting the number of suitable torpedo-dropping positions, many of the Swordfish had been armed with bombs and made a synchronised attack upon the cruisers and destroyers instead.[24] The six torpedo-armed Swordfish inflicted serious damage on three of the battleships. Two cruisers, two destroyers and other vessels were damaged or sunk.[25] The high manoeuvrability of the Swordfish was attributed with enabling the aircraft to evade intense anti-aircraft fire and hit the Italian ships.[26] The Battle of Taranto firmly established that naval aircraft were independently capable of immobilising an entire fleet and were an effective means of altering the balance of power.[24] The Japanese assistant naval attaché to Berlin, Takeshi Naito, visited Taranto to view the consequences of the attack; he later briefed the staff who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor.[27]

On 28 March 1941, a pair of Swordfish based at Crete contributed to the disabling of the Italian cruiser Pola during the Battle of Cape Matapan.[26] In May 1941, six Swordfish based at Shaibah, near Basra, Iraq, participated in the suppression of a revolt in the region, widely known now as the Anglo-Iraqi War. The aircraft conducted dive bombing attacks upon Iraqi barracks, fuel storage tanks and bridges.[26]

The Swordfish also flew a high level of anti-shipping sorties in the Mediterranean, many aircraft being based at Malta.[22] Guided by aerial reconnaissance from other RAF units, Swordfish would time their attacks to arrive at enemy convoys in the dark to elude German fighters, which were restricted to daytime operations. While there were never more than a total of 27 Swordfish aircraft stationed on the island at a time, the type succeeded in sinking an average of 50,000 tons of enemy shipping per month across a nine-month period.[22] During one record month, 98,000 tons of shipping were reportedly lost to the island's Swordfish-equipped strike force. The recorded Swordfish losses were low, especially in relation to the high sortie rate of the aircraft and in light of the fact that many aircraft lacked any blind-flying equipment, making night flying even more hazardous.[22]

Atlantic operations

In May 1941, Swordfish helped pursue and sink the German battleship Bismarck. On 24 May, nine Swordfish from HMS Victorious flew a late night sortie against the Bismarck under deteriorating weather conditions. Using ASV radar, the flight were able to spot and attack the ship, resulting in a single torpedo hit that only caused minor damage.[26][28] Bismarck's evasive manoeuvres, however, made it easier for her enemies to catch up.

On 26 May, Ark Royal launched two Swordfish strikes against Bismarck. The first failed to locate the ship. The second attack scored two torpedo hits, one of which jammed the ship's rudders at a 12° port helm.[29] This made Bismarck unmanoeuvrable and unable to escape to port in France. She sank after intense Royal Navy attack within 13 hours.[30] Some of the Swordfish flew so low that most of Bismarck's flak weapons could not depress enough to hit them.[31]

Throughout 1942, the Swordfish was progressively transferred away from the Royal Navy's fleet carriers as newer strike aircraft, such as the Fairey Albacore and Fairey Barracuda, were introduced.[30] In the submarine-hunter role, the Swordfish contributed to the Battle of the Atlantic, detecting and attacking the roaming U-boat packs that preyed upon merchant shipping between Britain and North America and in support of the Arctic convoys which delivered supplies from Britain to Russia.[30] Swordfish attacked submarines directly and guided destroyers to their locations. During one convoy battle, Swordfish from the escort carrier HMS Striker and Vindex flew over 1,000 hours on anti-submarine patrols in 10 days.[30]

One of the more innovative uses of the Swordfish was its role with merchant aircraft carriers ("MAC ships"). These were 20 civilian cargo or tanker ships modified to carry three or four aircraft each on anti-submarine duties with convoys. Three of these vessels were Dutch-manned, and several Swordfish of 860 (Dutch) Naval Air Squadron were typically deployed on board. The others were manned by aircrew from 836 Naval Air Squadron. At one time this was the largest squadron operating the type, with 91 aircraft.

Indian Ocean

In March and April 1941, during the East African campaign, Swordfish from HMS Eagle's 813 and 824 Naval Air Squadrons, operating from shore bases, were used against Italian land and naval targets in Massawa, East Africa. On 2 April 1941 four Italian destroyers, attempting to escape from Massawa, were attacked at sea by the Swordfish; the Nazario Sauro and Daniele Manin were sunk in dive-bombing attacks. The other two Italian destroyers, Pantera and Tigre were heavily damaged and driven ashore at Jedda and later destroyed by HMS Kingston.[32]

In 1942, Swordfish of 810 and 829 Squadrons on HMS Illustrious took part in the Battle of Madagascar. They dropped dummy paratroopers in support of the initial landings.[33] They later conducted anti-ship and anti-submarine operations in Diego Suarez Bay and bombed land targets in support of land operations during Operation Ironclad.[34] In the later Operation Jane, Swordfish were ready to support the attack on Tamatave, but in the event the town surrendered before they were needed.[35]

Home front

During early 1940, Swordfish aircraft of 812 Squadron under RAF Coastal Command started a campaign against enemy ports along the English Channel.[21] The aircraft routinely sortied to drop naval mines near such harbours. To increase range, additional fuel tanks were installed in the crew area and the third crew member was left behind.[21] RAF fighters often provided aerial cover where possible and occasionally counterattacked enemy air bases.[36]

The intensity of Coastal Command's Swordfish operations was drastically increased after the German invasion of the Low Countries, expanding to involve four Swordfish-equipped squadrons. Typically flying from Detling, Thorney Island, North Coates and St Eval, Swordfish crews were dispatched to strike strategic targets off the coasts of Netherlands and Belgium in daylight raids, during which they braved anti-aircraft fire and interception by Luftwaffe fighter aircraft.[21] Night time bombing raids were conducted against oil installations, power stations, and aerodromes.[21] After the Allied defeat in the Battle of France and the signing of the French Armistice of 22 June 1940, Swordfish focused their activities against ports that might be used for a German invasion of the United Kingdom This included security patrols and spotting for naval bombardments.[21]

In February 1942, the shortcomings of the Swordfish were starkly demonstrated during a German naval fleet movement known as the Channel Dash. Six Swordfish led by Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde sortied from Manston to intercept the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau as they traversed the English Channel towards Germany.[30] When the Swordfish formation arrived and commenced an initial attack run coming astern of the ships, the Swordfish were intercepted by roughly 15 Messerschmitt Bf 109 monoplane fighter aircraft; the aerial battle was extremely one-sided, quickly resulting in the loss of all Swordfish while no damage was achieved upon the ships themselves.[30] The lack of fighter cover was a contributing factor for the heavy losses experienced; only 10 of 84 promised fighters were available. Thirteen of the 18 Swordfish crew involved were killed. Esmonde, who had previously led an attack on Bismarck, was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously.[30]

The courage of the Swordfish crews was noted by commanders on both sides. British Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay wrote "In my opinion the gallant sortie of these six Swordfish aircraft constitutes one of the finest exhibitions of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty the war had ever witnessed". German Vice-Admiral Otto Ciliax remarked on "the mothball attack of a handful of ancient planes, piloted by men whose bravery surpasses any other action by either side that day."[37]

However, as a result of this incident, Swordfish were quickly withdrawn from the torpedo-bomber role in favour of more anti-submarine duties. Armed with depth charges and rockets, the aircraft were good submarine killers.[30]

In the anti-submarine role, the Swordfish pioneered the naval use of air to surface vessel (ASV) radar, allowing the aircraft to effectively locate surface ships at night and through clouds.[38] Swordfish were flying missions with the radar by October 1941.[30] In December 1941, a Swordfish based in Gibraltar located and sank a U-boat, the first such kill to be achieved by an aircraft during nighttime. On 23 May 1943, a rocket-equipped Swordfish destroyed German submarine U-752 off the coast of Ireland, the first kill achieved with this weapon.[30]

Later use

Towards the end of the war, No. 119 Squadron RAF operated Swordfish Mark IIIs with centimetric radar from airfields in Belgium. Their main task was to hunt at night for German midget submarines in the North Sea and off the Dutch coast.[39] The radar was able to detect ships at a range of around 25 miles (40 km).[40] One of the aircraft operated by 119 Squadron in this role survives and is part of the collection of the Imperial War Museum (see Surviving aircraft).

By 1945, nine front-line squadrons were still equipped with Swordfish.[30] Overall, Swordfish sank 14 U-boats. The Swordfish was intended to be replaced by the Fairey Albacore, also a biplane, but it outlived its intended successor until succeeded by the Fairey Barracuda monoplane torpedo bomber. Operational sorties of the Swordfish continued into January 1945. The last active missions are believed to have been anti-shipping operations off the coast of Norway by FAA Squadrons 835 and 813, where the Swordfish's manoeuvrability was essential.[41] The last operational squadron, 836 Naval Air Squadron, which had last been engaged in providing resources for the MAC ships, was disbanded on 21 May 1945, soon after the end of World War II in Europe.[42] In the northern summer of 1946, the last training squadron equipped with the type was disbanded, after which only a few examples remained in service to perform sundry duties at a few naval air stations.[43]

Variants

- Swordfish I

- First production series.

- Swordfish I

- Version equipped with floats, for use from catapult-equipped warships.

- Swordfish II

- Version with metal lower wings to enable the mounting of rockets, introduced in 1943.

- Swordfish III

- Version with added large centimetric radar unit, introduced in 1943.

- Swordfish IV

- Last version (production ended in 1944), with an enclosed cabin for use by the RCAF

Operators

.svg.png.webp) Australia

Australia

- Royal Australian Air Force

- Six aircraft were used by No. 25 Squadron RAAF in 1942.[44]

- Royal Australian Air Force

.svg.png.webp) Canada

Canada

_crowned.svg.png.webp) Italy

Italy

- Regia Aeronautica

- Swordfish 4A was first to fall into Italian hands in the aftermath of the Battle of Taranto, in poor condition.

- Swordfish K8422 of HMS Eagle was shot down and captured during a raid on Maritza airfield, Rhodes on 4 September 1940. Evaluated at Guidonia Test Centre and kept serviceable until mid-1941.

- Swordfish P4127 (coded 4F) of 820 squadron on HMS Ark Royal, involved in bombing raid on Cagliari, Sardinia. Hit by ground fire, it force-landed on the enemy airfield at Elmas on 2 August 1940. The crew were taken prisoner and the aircraft captured intact. Caproni repaired it locally and fitted it with an Alfa Romeo 125 engine. It was taken to the Stabilimento Costruzioni Aeronautiche in Guidonia on 27 February 1941. It was still listed as being there on 6 April 1942.[45]

- Regia Aeronautica

Netherlands

Netherlands

- Royal Netherlands Navy

- Dutch Naval Aviation Service in exile in the United Kingdom

- Royal Netherlands Navy

.svg.png.webp) Spain

Spain

- Ejercito del Aire

- Swordfish W5843 of 813 squadron at North Front, Gibraltar lost its bearings during an anti-submarine sweep and force landed between Ras el Farea and Pota Pescadores, in Spanish Morocco, on 30 April 1942. The crew were all interned. The final fate of the aircraft is not known.[45]

- Swordfish P4073 of 700 squadron of HMS Malaya ran out of fuel whilst shadowing the German battleship Scharnhorst on 8 March 1941.[46][47] Aircraft and crew were recovered by the Spanish liner Cabo de Buena Esperanza off Canary Islands and interned in Spain.[48] The Swordfish was put on the strength of the Spanish air force as HR6-1 on 6 December 1943 with 54 Escuadrilla, Puerto de le Cruz, Tenerife, Canary Islands. Retired March 1945 at Las Palmas, Gran Canaria.[45]

- Ejercito del Aire

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- Royal Air Force[49]

- No. 8 Squadron RAF

- No. 119 Squadron RAF

- No. 202 Squadron RAF

- No. 209 Squadron RAF

- No. 273 Squadron RAF

- No. 613 Squadron RAF

- No. 3 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit (No. 3 AACU), Malta and Gibraltar

- No. 4 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit (No. 4 AACU), Singapore

- 9 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit

- Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm[50] (prior to May 1939 part of RAF)

- 700 Naval Air Squadron

- 701 Naval Air Squadron

- 702 Naval Air Squadron

- 705 Naval Air Squadron (float-equipped aircraft from the battlecruisers Repulse and Renown)

- 710 Naval Air Squadron

- 722 Naval Air Squadron

- 726 Naval Air Squadron

- 727 Naval Air Squadron

- 728 Naval Air Squadron

- 730 Naval Air Squadron

- 731 Naval Air Squadron

- 733 Naval Air Squadron

- 735 Naval Air Squadron

- 737 Naval Air Squadron

- 739 Naval Air Squadron

- 740 Naval Air Squadron

- 741 Naval Air Squadron

- 742 Naval Air Squadron

- 743 Naval Air Squadron

- 744 Naval Air Squadron

- 747 Naval Air Squadron

- 753 Naval Air Squadron

- 759 Naval Air Squadron

- 763 Naval Air Squadron

- 764 Naval Air Squadron

- 765 Naval Air Squadron

- 766 Naval Air Squadron

- 767 Naval Air Squadron

- 768 Naval Air Squadron

- 769 Naval Air Squadron

- 770 Naval Air Squadron

- 771 Naval Air Squadron

- 772 Naval Air Squadron

- 773 Naval Air Squadron

- 774 Naval Air Squadron

- 775 Naval Air Squadron

- 776 Naval Air Squadron

- 777 Naval Air Squadron

- 778 Naval Air Squadron

- 779 Naval Air Squadron

- 780 Naval Air Squadron

- 781 Naval Air Squadron

- 782 Naval Air Squadron

- 783 Naval Air Squadron

- 785 Naval Air Squadron

- 786 Naval Air Squadron

- 787 Naval Air Squadron

- 788 Naval Air Squadron

- 789 Naval Air Squadron

- 791 Naval Air Squadron

- 794 Naval Air Squadron

- 796 Naval Air Squadron

- 797 Naval Air Squadron

- 810 Naval Air Squadron

- 811 Naval Air Squadron

- 812 Naval Air Squadron

- 814 Naval Air Squadron

- 815 Naval Air Squadron

- 816 Naval Air Squadron

- 817 Naval Air Squadron, transferred to South Africa in 1945

- 818 Naval Air Squadron

- 819 Naval Air Squadron

- 820 Naval Air Squadron

- 821 Naval Air Squadron

- 822 Naval Air Squadron

- 823 Naval Air Squadron

- 824 Naval Air Squadron

- 825 Naval Air Squadron

- 826 Naval Air Squadron

- 828 Naval Air Squadron

- 829 Naval Air Squadron

- 830 Naval Air Squadron

- 833 Naval Air Squadron

- 834 Naval Air Squadron

- 835 Naval Air Squadron

- 836 Naval Air Squadron

- 837 Naval Air Squadron

- 838 Naval Air Squadron

- 840 Naval Air Squadron

- 841 Naval Air Squadron

- 842 Naval Air Squadron

- 860 Naval Air Squadron

- 886 Naval Air Squadron

- Royal Air Force[49]

Surviving aircraft

.jpg.webp)

A large proportion of the currently surviving aircraft were recovered from the farm of Canadian Ernie Simmons.[51]

- Canada

- NS122 – Swordfish II on static display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.[52]

- HS469 – Swordfish IV on display at the Shearwater Aviation Museum in Nova Scotia. It was restored to airworthy condition and flew once, in 1994.[53]

- HS498 – Swordfish IV in storage at the Reynolds-Alberta Museum in Wetaskiwin, Alberta.[54]

- Malta

- HS491 – Swordfish IV under restoration at the Malta Aviation Museum in Ta' Qali, Attard.[55]

- United Kingdom

- HS503 – Swordfish IV in storage at the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford in Cosford, Shropshire.[56]

- HS554 – Swordfish III under restoration to airworthy with private owners in White Waltham, Berkshire.[57] Restored to flight in 2006, it was previously owned by Vintage Wings of Canada. After being grounded for several years, it was sold to the current owners in 2019.[58][59]

- HS618 – Swordfish II on static display at the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovil, Somerset.[60]

- LS326 – Swordfish II airworthy with Navy Wings in Ilchester, Somerset.[61]

- NF370 – Swordfish III on static display at the Imperial War Museum Duxford in Duxford, Cambridgeshire. It was built in 1944. It was operated by No. 119 Squadron RAF, which was given the task of patrolling the North Sea in search of German torpedo boats and midget submarines. It has been at the Imperial War Museum Duxford since 1986. In 1998, a restoration project began that returned the airframe to an airworthy condition, although it was fitted with a non-functional Pegasus engine.[40]

- W5856 – Swordfish I airworthy with Navy Wings in Ilchester, Somerset.[62]

- United States

- HS164 – Swordfish IV on display at the American Airpower Heritage Museum of the Commemorative Air Force in Dallas, Texas.[63]

Specifications (Swordfish I)

Data from Fairey Aircraft since 1915,[64] The Fairey Swordfish Mks. I-IV[65]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3 - pilot, observer, and radio operator/rear gunner (observer's position frequently replaced with auxiliary fuel tank)

- Length: 35 ft 8 in (10.87 m)

- Wingspan: 45 ft 6 in (13.87 m)

- Width: 17 ft 3 in (5.26 m) wings folded

- Height: 12 ft 4 in (3.76 m)

- Wing area: 607 sq ft (56.4 m2)

- Airfoil: RAF 28[66]

- Empty weight: 4,195 lb (1,903 kg)

- Gross weight: 7,580 lb (3,438 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Bristol Pegasus IIIM.3 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 690 hp (510 kW)

- Propellers: 3-bladed metal fixed-pitch propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 143 mph (230 km/h, 124 kn) with torpedo at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg) and 5,000 ft (1,524 m)

- Range: 522 mi (840 km, 454 nmi) normal fuel, carrying torpedo[67]

- Endurance: 5 hours 30 minutes

- Service ceiling: 16,500 ft (5,000 m) at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg)

- Rate of climb: 870 ft/min (4.4 m/s) at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg) at sea level

- 690 ft/min (210.3 m/min) at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg) and 5,000 ft (1,524 m)

Armament

- Guns: ** 1 × fixed, forward-firing .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers machine gun in upper right fuselage, breech in cockpit, firing over engine cowling

- 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis or Vickers K machine gun in rear cockpit

- Rockets: 8 × "60 lb" RP-3 rocket projectiles (Mk.II and later)

- Bombs: 1 × 1,670 lb (760 kg) torpedo or 1,500 lb (700 kg) mine under fuselage or 1,500 lb total of bombs under fuselage and wings.

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- Stott 1971, p. 21.

- Stott 1971, pp. 21–22.

- Stott 1971, p. 22.

- Stott 1971, pp. 22–23.

- Stott 1971, p. 23.

- Stott 1971, p. 24.

- Stott 1971, pp. 24–25.

- Stott 1971, p. 25. Blackburn-built Swordfish were nicknamed 'Blackfish'.

- Stott 1971, p. 26.

- Bishop, Chris (2002). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 403. ISBN 978-1-58663-762-0.

- Lamb 2001

- Emmott, Norman W. "Airborne Torpedoes". United States Naval Institute Proceedings, August 1977.

- Campbell 1985, p. 87.

- Smith, p. 66.

- Smith, Peter (2014). Combat Biplanes of World War II. United Kingdom: Pen & Sword. p. 68. ISBN 978-1783400546.

- Wragg 2003, p. 142.

- Stott 1971, pp. 23–24.

- Stott 1971, pp. 26, 28.

- Ballantyne, Iain (2001). Warspite: From Jutland hero to cold war warrior. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-84884-350-9.

- Whitley, M. J. (1983). Destroyer! : German destroyers in World War II. London: Arms and Armour. p. 127. ISBN 0-85368-258-5. OCLC 10360808.

- Stott 1971, p. 28.

- Stott 1971, p. 31.

- Stott 1971, pp. 31, 34.

- Stott 1971, p. 34.

- Stott 1971, pp. 34, 37.

- Stott 1971, p. 37.

- Lowry and Wellham 2000, p. 92.

- Garzke & Dulin 1985, pp. 229–230.

- Kennedy 2002, p. 166.

- Stott 1971, p. 38.

- Kennedy 2002, pp. 112, 165.

- Harrison 1987, pp.61-62

- Phillips, Russell (5 May 2021). A Strange Campaign: The Battle for Madagascar. Shilka Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 9781912680276.

- Phillips, Russell (5 May 2021). A Strange Campaign: The Battle for Madagascar. Shilka Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 9781912680276.

- Phillips, Russell (5 May 2021). A Strange Campaign: The Battle for Madagascar. Shilka Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9781912680276.

- Stott 1971, pp. 28, 31.

- Kemp, pp. 199–200.

- Harrison 2001, p. 9.

- "ROYAL AIR FORCE COASTAL COMMAND, 1939–1945". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- Parsons, Gary (2005). "Back in Black". Air-Scene UK. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Wragg 2005, pp. 127–131.

- Stott 1971, pp. 38–40.

- Stott 1971, p. 40.

- ADF-Serials RAAF Fairey Swordfish Mk.I

- "Captured Fleet Air Arm Aircraft". fleetairarmarchive.net. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - HMS MALAYA – Queen Elizabeth-class 15in gun Battleship including Convoy Escort Movements

- Sturtivant, p. 65.

- Aranduy Laiseca, Javier (12 November 2013). "Incidentes aéreos en España en la SGM: Fairey Swordfish". Incidentes aéreos en España en la SGM (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Thomas 1998, pp. 73–77.

- Thetford 1991, p. 149.

- Whittemore, Ray. "The Simmons Collection". Spitfire Emporium. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Fairey Swordfish II". Ingenium. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "The Swordfish HS469". Shearwater Aviation Museum. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Aviation". Reynolds Museum. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Fairey Swordfish HS491". Malta Aviation Museum. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Goodall, Geoffrey (22 March 2019). "FAIREY SWORDFISH" (PDF). Geoff Goodall's Aviation History Site. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Swordfish HS554". Navy Wings. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "The Commander Terry Goddard Blackburn-Fairey Swordfish Mk III". Vintage Wings of Canada. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Canadian 'Stringbag' for the UK". Aeroplane. Vol. 47, no. 8. August 2019. p. 7. ISSN 0143-7240.

- "Fairey Swordfish II (HS618)". Fleet Air Arm Museum. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Swordfish LS326". Navy Wings. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Swordfish W5856". Navy Wings. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Airframe Dossier - Fairey Swordfish IV, s/n HS164 RCN, c/r N2235R". Aerial Visuals. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Taylor 1974, p. 259.

- Stott 1971, p. 43.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Taylor 1974, p. 260:

- 1,030 mi (895 nmi; 1,658 km) reconnaissance with no bombs and extra fuel

Bibliography

- Brown, Eric, CBE, DCS, AFC, RN.; William Green and Gordon Swanborough. "Fairey Swordfish". Wings of the Navy, Flying Allied Carrier Aircraft of World War Two. London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1980, pp. 7–20. ISBN 0-7106-0002-X.

- Campbell, John. Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Harrison, W.A. Fairey Swordfish and Albacore. Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press, 2002. ISBN 1-86126-512-3.

- Harrison, W.A. Fairey Swordfish in Action (Aircraft Number 175). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 2001. ISBN 0-89747-421-X.

- Harrison, W.A. Swordfish at War. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd., 1987. ISBN 0-7110-1676-3.

- Harrison, W.A. Swordfish Special. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd., 1977. ISBN 0-7110-0742-X.

- Kilbracken, Lord. Bring Back My Stringbag: A Swordfish Pilot at War. London: Pan Books Ltd, 1980. ISBN 0-330-26172-X. First published by Peter Davies Ltd, 1979.

- Lamb, Charles. To War in a Stringbag. London: Cassell & Co., 2001. ISBN 0-304-35841-X.

- Lowe, Malcolm V. Fairey Swordfish: Plane Essentials No.3. Wimborne, UK: Publishing Solutions (www) Ltd., 2009. ISBN 978-1-906589-02-8.

- Lowry, Thomas P. and John Wellham.The Attack on Taranto: Blueprint for Pearl Harbor. London: Stackpole Books, 2000. ISBN 0-8117-2661-4.

- Kemp, P.K. Key to Victory: The Triumph of British Sea Power in World War II. New York: Little, Brown, 1957.

- Kennedy, Ludovic. Pursuit: The Sinking of the Bismarck. Bath, UK: Chivers Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7540-0754-8.

- Roba, Jean-Louis & Cony, Christophe (August 2001). "Donnerkeil: 12 février 1942" [Operation Donnerkeil: 12 February 1942]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (101): 10–19. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Roba, Jean-Louis & Cony, Christophe (September 2001). "Donnerkeil: 12 février 1942". Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (102): 46–53. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Smith, Peter C. Dive Bomber!. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-87021-930-6.

- Stott, Ian G. The Fairey Swordfish Mks. I-IV (Aircraft in Profile 212). Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications, 1971. OCLC 53091961

- Sturtivant, Ray. The Swordfish Story. London: Cassell & Co., 1993 (2nd Revised edition 2000). ISBN 0-304-35711-1.

- Taylor, H.A, Fairey Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1974. ISBN 0-370-00065-X.

- Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft Since 1912. London: Putnam, Fourth edition, 1978. ISBN 0-370-30021-1.

- Thetford, Owen (1991). British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London, UK: Putnam Aeronautical Books, an imprint of Conway Maritime Press Ltd. ISBN 0-85177-849-6.

- Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft Since 1912. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

- Thomas, Andrew. "Light Blue 'Stringbags': The Fairey Swordfish in RAF Service". Air Enthusiast, No. 78, November/December 1998, pp. 73–77. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Willis, Matthew. Fleet Air Arm Legends 2 - Fairey Swordfish. Horncastle, UK: Mortons Books, 2022. ISBN 9781911658498.

- Wragg, David. The Escort Carrier in World War II. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-220-0.

- Wragg, David. Stringbag: The Fairey Swordfish at War. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Books, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-130-1.

- Wragg, David. Swordfish: The Story of the Taranto Raid. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2003. ISBN 0-297-84667-1.

External links

- Swordfish Story of the Torpedoing of the Bismarck

- "Stringbag Plus" a 1946 Flight article on flying the Swordfish