Taiwan under Japanese rule

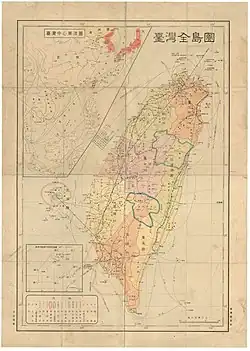

The island of Taiwan, together with the Penghu Islands, became a dependency of Japan in 1895, when the Qing dynasty ceded Fujian-Taiwan Province in the Treaty of Shimonoseki after the Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese War. The short-lived Republic of Formosa resistance movement was suppressed by Japanese troops and quickly defeated in the Capitulation of Tainan, ending organized resistance to Japanese occupation and inaugurating five decades of Japanese rule over Taiwan. The entity, historically known in English as Formosa, had an administrative capital located in Taihoku (Taipei) led by the Governor-General of Taiwan.[1]

Taiwan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895–1945 | |||||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||||

| National seal: 台灣總督之印 Seal of the Governor-General of Taiwan  National badge: 臺字章 Daijishō  | |||||||||||

Taiwan within the Empire of Japan | |||||||||||

| Status | Part of the Empire of Japan | ||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | |||||||||||

| Official languages | Japanese | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Taiwanese Hakka Formosan languages | ||||||||||

| Religion | State Shinto Buddhism Taoism Confucianism Chinese folk religion | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) |

| ||||||||||

| Government | Government-General | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1895–1912 | Meiji | ||||||||||

• 1912–1926 | Taishō | ||||||||||

• 1926–1945 | Shōwa | ||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||

• 1895–1896 (first) | Kabayama Sukenori | ||||||||||

• 1944–1945 (last) | Rikichi Andō | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Empire of Japan | ||||||||||

| 17 April 1895 | |||||||||||

| 21 October 1895 | |||||||||||

| 27 October 1930 | |||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||

| 25 October 1945 | |||||||||||

| 28 April 1952 | |||||||||||

| 5 August 1952 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Taiwanese yen | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | TW | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||

| Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) "Taiwan" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣 or 台灣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 日治臺灣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 日治台湾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | だいにっぽんていこくたいわん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katakana | ダイニッポンテイコクタイワン | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 大日本帝國臺灣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 大日本帝国台湾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

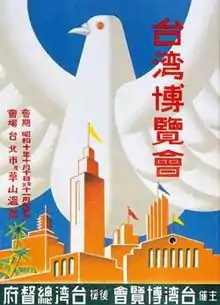

Taiwan was Japan's first colony and can be viewed as the first step in implementing their "Southern Expansion Doctrine" of the late 19th century. Japanese intentions were to turn Taiwan into a showpiece "model colony" with much effort made to improve the island's economy, public works, industry, cultural Japanization, and support the necessities of Japanese military aggression in the Asia-Pacific.[2] Japan established monopolies and by 1945, had taken over all the sales of opium, salt, camphor, tobacco, alcohol, matches, weights and measures, and petroleum in the island.[3]

Japanese administrative rule of Taiwan ended following the surrender of Japan in September 1945 during the World War II period, and the territory was placed under the control of the Republic of China (ROC) with the issuing of General Order No. 1.[4] Japan formally renounced its sovereignty over Taiwan in the Treaty of San Francisco effective April 28, 1952. The experience of Japanese rule continues to cause divergent views among several issues in Post-WWII Taiwan, such as the February 28 massacre of 1947, Taiwan Retrocession Day, Taiwanese comfort women, national identity, ethnic identity, and the formal Taiwan independence movement.

History

Early contact

The Japanese had been trading for Chinese products in Taiwan (formerly known as "Highland nation" (Japanese: 高砂国, Hepburn: Takasago-koku)) since before the Dutch arrived in 1624. In 1593, Toyotomi Hideyoshi planned to incorporate Taiwan into his empire and sent an envoy with a letter demanding tribute.[5] The letter was never delivered since there was no authority to receive it. In 1609, the Tokugawa shogunate sent Harunobu Arima on an exploratory mission of the island.[6] In 1616, Nagasaki official Murayama Tōan sent 13 vessels to conquer Taiwan. The fleet was dispersed by a typhoon and the one junk that reached Taiwan was ambushed by headhunters, after which the expedition left and raided the Chinese coast instead.[5][7][8]

In 1625, Batavia ordered the governor of Taiwan to prevent the Japanese from trading. The Chinese silk merchants refused to sell to the company because the Japanese paid more. The Dutch also restricted Japanese trade with the Ming dynasty. In response, the Japanese took on board 16 inhabitants from the aboriginal village of Sinkan and returned to Japan. Suetsugu Heizō Masanao housed the Sinkanders in Nagasaki. Batavia sent a man named Peter Nuyts to Japan where he learned about the Sinkanders. The shogun declined to meet the Dutch and gave the Sinkanders gifts. Nuyts arrived in Taiwan before the Sinkanders and refused to allow them to land before the Sinkanders were jailed and their gifts confiscated. The Japanese took Nuyts hostage and only released him in return for their safe passage back to Japan with 200 picols of silk as well as the Sinkanders' freedom and the return of their gifts.[9] The Dutch blamed the Chinese for instigating the Sinkanders.[10]

The Dutch dispatched a ship to repair relations with Japan but it was seized and its crew imprisoned upon arrival. The loss of the Japanese trade made the Taiwanese colony far less profitable and the authorities in Batavia considered abandoning it before the Council of Formosa urged them to keep it unless they wanted the Portuguese and Spanish to take over. In June 1630, Suetsugu died and his son, Masafusa, allowed the company officials to reestablish communication with the shogun. Nuyts was sent to Japan as a prisoner and remained there until 1636 when he returned to the Netherlands. After 1635, the shogun forbade Japanese from going abroad and eliminated the Japanese threat to the company. The VOC expanded into previous Japanese markets in Southeast Asia. In 1639, the shogun ended all contact with the Portuguese, the company's major silver trade competitor.[9]

The Kingdom of Tungning's merchant fleets continued to operated between Japan and Southeast Asian countries, reaping profits as a center of trade. They extracted a tax from traders for safe passage through the Taiwan Strait. Zheng Taiwan held a monopoly on certain commodities such as deer skin and sugarcane, which sold at a high price in Japan.[11]

Mudan incident

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan vessel shipwrecked on the southeastern tip of Taiwan and 54 sailors were killed by aborigines.[12] The survivors encountered aboriginal men, presumably Paiwanese, who they followed to a small settlement, Kuskus, where they were given food and water. They claim they were robbed by their Kuskus hosts during the night and in the morning they were ordered to stay put while hunters left to search for game to provide a feast. The Ryukyuans departed while the hunting party was away and found shelter in the home of a trading-post serviceman, Deng Tianbao. The Paiwanese men found the Ryukyuans and slaughtered them. Nine Ryukyuans hid in Deng's home. They moved to another settlement where they found refuge with Deng's son-in-law, Yang Youwang. Yang arranged for the ransom of three men and sheltered the survivors before sending them to Taiwan Prefecture (modern Tainan). The Ryukuans headed home in July 1872.[13] The shipwreck and murder of the sailors came to be known as the Mudan incident, although it did not take place in Mudan (J. Botan), but at Kuskus (Gaoshifo).[14]

The Mudan incident did not immediately cause any concern in Japan. A few officials knew of it by mid-1872 but it was not until April 1874 that it became an international concern. The repatriation procedure in 1872 was by the books and had been a regular affair for several centuries. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the Qing had settled 401 Ryukyuan shipwreck incidents both on the coast of mainland China and Taiwan. The Ryukyu Kingdom did not ask Japanese officials for help regarding the shipwreck. Instead its king, Shō Tai, sent a reward to Chinese officials in Fuzhou for the return of the 12 survivors.[15]

Japanese invasion (1874)

The Imperial Japanese Army started urging the government to invade Taiwan in 1872.[16] The king of Ryukyu was dethroned by Japan and preparations for an invasion of Taiwan were undertaken in the same year. Japan blamed the Qing for not ruling Taiwan properly and claimed that the perpetrators of the Mudan incident were "all Taiwan savages beyond Chinese education and law."[16] Therefore Japan reasoned that the Taiwanese aboriginal people were outside the borders of China and Qing China consented to Japan's invasion.[17] Japan sent Kurooka Yunojo as a spy to survey eastern Taiwan.[18]

In October 1872, Japan sought compensation from the Qing dynasty of China, claiming the Kingdom of Ryūkyū was part of Japan. In May 1873, Japanese diplomats arrived in Beijing and put forward their claims; however, the Qing government immediately rejected Japanese demands on the ground that the Kingdom of Ryūkyū at that time was an independent state and had nothing to do with Japan. The Japanese refused to leave and asked if the Chinese government would punish those "barbarians in Taiwan". The Qing authorities explained that there were two kinds of aborigines in Taiwan: those directly governed by the Qing, and those unnaturalized "raw barbarians... beyond the reach of Chinese culture. Thus could not be directly regulated." They indirectly hinted that foreigners traveling in those areas settled by indigenous people must exercise caution. The Qing dynasty made it clear to the Japanese that Taiwan was definitely within Qing jurisdiction, even though part of that island's aboriginal population was not yet under the influence of Chinese culture. The Qing also pointed to similar cases all over the world where an aboriginal population within a national boundary was not under the influence of the dominant culture of that country.[19]

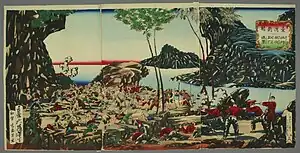

Japan announced that they were attacking aboriginals in Taiwan on 3 May 1874. In early May, Japanese advance forces established camp at Langqiao Bay. On 17 May, Saigō Jūdō led the main force, 3,600 strong, aboard four warships in Nagasaki head to Tainan.[20] A small scouting party was ambushed and the Japanese camp sent 250 reinforcements to search the villages. The next day, Samata Sakuma encountered Mudan fighters, around 70 strong, occupying a commanding height. A twenty-men party climbed the cliffs and shot at the Mudan people, forcing them to flee.[21] On 6 June, the Japanese emperor issued a certificate condemning the Taiwan "savages" for killing our "nationals", the Ryukyuans killed in southeastern Taiwan.[22] The Japanese army split into three forces and headed in different directions to burn the aboriginal villages. On 3 June, they burnt all the villages that had been occupied. On 1 July, the new leader of the Mudan tribe and the chief of Kuskus surrendered.[23] The Japanese settled in and established large camps with no intention of withdrawing, but in August and September 600 soldiers fell ill. The death toll rose to 561. Negotiations with Qing China began on 10 September. The Western Powers pressured China not to cause bloodshed with Japan as it would negatively impact the coastal trade. The resulting Peking Agreement was signed on 30 October. Japan gained the recognition of Ryukyu as its vassal and an indemnity payment of 500,000 taels. Japanese troops withdrew from Taiwan on 3 December.[24]

Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War broke out between Qing dynasty China and Japan in 1894 following a dispute over the sovereignty of Korea. The acquisition of Taiwan by Japan was the result of Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi's "southern strategy" adopted during the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95 and the following diplomacy in the spring of 1895. Prime Minister Hirobumi's southern strategy, supportive of Japanese navy designs, paved the way for the occupation of Penghu Islands in late March as a prelude to the takeover of Taiwan. Soon after, while peace negotiations continued, Hirobumi and Mutsu Munemitsu, his minister of foreign affairs, stipulated that both Taiwan and Penghu were to be ceded by imperial China.[25] Li Hongzhang, China's chief diplomat, was forced to accede to these conditions as well as to other Japanese demands, and the Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on April 17, then duly ratified by the Qing court on 8 May. The formal transference of Taiwan and Penghu took place on a ship off the Kīrun coast on June 2. This formality was conducted by Li's adopted son, Li Ching-fang, and Admiral Kabayama Sukenori, a staunch advocate of annexation, whom Itō had appointed as governor-general of Taiwan.[26][27]

The annexation of Taiwan was also based on considerations of productivity and ability to provide raw materials for Japan's expanding economy and to become a ready market for Japanese goods. Taiwan's strategic location was deemed advantageous as well. As envisioned by the navy, the island would form a southern bastion of defense from which to safeguard southernmost China and southeastern Asia.[28]

The period of Japanese rule in Taiwan has been divided into three periods under which different policies were prevalent: military suppression (1895–1915), dōka (同化): assimilation (1915–37), and kōminka (皇民化): Japanization (1937–45). A separate policy for aborigines was implemented.[29][30]

Armed resistance

Because Taiwan was ceded by treaty, the period that followed is referred by some as the "colonial period," while others who focus on the fact that it was the culmination of war refer to it as the "occupation period." The cession ceremony took place on board a Japanese vessel because the Chinese delegate feared reprisal from the residents of Taiwan.[31] The loss of Taiwan would become an irredentist rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed.[32]

The colonial authorities encountered violent opposition in much of Taiwan. Five months of sustained warfare occurred after the invasion of Taiwan in 1895 and partisan attacks continued until 1902. For the first two years the colonial authority relied mainly on military force and local pacification efforts. Disorder and panic were prevalent in Taiwan after Penghu was seized by Japan in March 1895. On 20 May, Qing officials were ordered to leave their posts. General mayhem and destruction ensued in the following months.[33]

Japanese forces landed on the coast of Keelung on 29 May and Tamsui's harbor was bombarded. Remnant Qing units and Guangdong irregulars briefly fought against Japanese forces in the north. After the fall of Taipei on 7 June, local militia and partisan bands continued the resistance. In the south, a small Black Flag force led by Liu Yongfu delayed Japanese landings. Governor Tang Jingsong attempted to carry out anti-Japanese resistance efforts as the Republic of Formosa, however he still professed to be a Qing loyalist. The declaration of a republic was, according to Tang, to delay the Japanese so that Western powers might be compelled to defend Taiwan.[33] The plan quickly turned to chaos as the Green Standard Army and Yue soldiers from Guangxi took to looting and pillaging Taiwan. Given the choice between chaos at the hands of bandits or submission to the Japanese, Taipei's gentry elite sent Koo Hsien-jung to Keelung to invite the advancing Japanese forces to proceed to Taipei and restore order.[34] The Republic, established on 25 May, disappeared 12 days later when its leaders left for the mainland.[33] Liu Yongfu formed a temporary government in Tainan but escaped to the mainland as well as Japanese forces closed in.[35] Between 200,000 and 300,000 people fled Taiwan in 1895.[36][37] Chinese residents in Taiwan were given the option of selling their property and leaving by May 1897, or become Japanese citizens. From 1895 to 1897, an estimated 6,400 people, mostly gentry elites, sold their property and left Taiwan. The vast majority did not have the means or will to leave.[38][39][40]

Upon Tainan's surrender, Kabayama declared Taiwan pacified, however his proclamation was premature. In December, a series of anti-Japanese uprisings occurred in northern Taiwan, and would continue to occur at a rate of roughly one per month. Armed resistance by Hakka villagers broke out in the south. A series of prolonged partisan attacks, led by "local bandits" or "rebels", lasted throughout the next seven years. After 1897, uprisings by Chinese nationalists were commonplace. Luo Fuxing, a member of the Tongmenghui organization preceding the Kuomintang, was arrested and executed along with two hundred of his comrades in 1913.[41] Japanese reprisals were often more brutal than the guerilla attacks staged by the rebels. In June 1896, 6,000 Taiwanese were slaughtered in the Yunlin Massacre. From 1898 to 1902, some 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed in addition to the 6,000–14,000 killed in the initial resistance war of 1895.[35][42][43] During the conflict, 5,300 Japanese were killed or wounded, and 27,000 were hospitalized.[44]

Rebellions were often caused by a combination of unequal colonial policies on local elites and extant millenarian beliefs of the local Taiwanese and plains Aborigines.[45] Ideologies of resistance drew on different ideals such as Taishō democracy, Chinese nationalism, and nascent Taiwanese self-determination.[46] Support for resistance was partly class-based and many of the wealthy Han people in Taiwan preferred the order of colonial rule to the lawlessness of insurrection.[47]

"The cession of the island to Japan was received with such disfavour by the Chinese inhabitants that a large military force was required to effect its occupation. For nearly two years afterwards, a bitter guerrilla resistance was offered to the Japanese troops, and large forces – over 100,000 men, it was stated at the time – were required for its suppression. This was not accomplished without much cruelty on the part of the conquerors, who, in their march through the island, perpetrated all the worst excesses of war. They had, undoubtedly, considerable provocation. They were constantly attacked by ambushed enemies, and their losses from battle and disease far exceeded the entire loss of the whole Japanese army throughout the Manchurian campaign. But their revenge was often taken on innocent villagers. Men, women, and children were ruthlessly slaughtered or became the victims of unrestrained lust and rapine. The result was to drive from their homes thousands of industrious and peaceful peasants, who, long after the main resistance had been completely crushed, continued to wage a vendetta war, and to generate feelings of hatred which the succeeding years of conciliation and good government have not wholly eradicated." – The Cambridge Modern History, Volume 12[48]

Major armed resistance was largely crushed by 1902 but minor rebellions started occurring again in 1907, such as the Beipu uprising by Hakka and Saisiyat people in 1907, Luo Fuxing in 1913 and the Tapani Incident of 1915.[45][49] The Beipu uprising occurred on 14 November 1907 when a group of Hakka insurgents killed 57 Japanese officers and members of their family. In the following reprisal, 100 Hakka men and boys were killed in the village of Neidaping.[50] Luo Fuxing was an overseas Taiwanese Hakka involved with the Tongmenghui. He planned to organize a rebellion against the Japanese with 500 fighters, resulting in the execution of more than 1,000 Taiwanese by Japanese police. Luo was killed on 3 March 1914.[42][51] In 1915, Yu Qingfang organized a religious group that openly challenged Japanese authority. Aboriginals and Han forces led by Chiang Ting and Yu stormed multiple Japanese police stations. In what is known as the Tapani incident, 1,413 members of Yu's religious group were captured. Yu and 200 of his followers were executed.[52] After the Tapani rebels were defeated, Andō Teibi ordered Tainan's Second Garrison to retaliate through massacre. Military police in Tapani and Jiasian announced that they would pardon any anti-Japanese militants and that those who had fled into the mountains should return to their village. Once they returned, the villagers were told to line up in a field, dig holes, and were then executed by firearm. According to oral tradition, at least 5,000–6,000 people died in this incident.[53][54][55]

Non-violent resistance

Nonviolent means of resistance such as the Taiwanese Cultural Association (TCA), founded by Chiang Wei-shui in 1921, continued to exist after most violent means were exhausted. Chiang was born in Yilan in 1891 and was raised on a Confucian education paid by a father who identified as a Han Chinese. In 1905, Chiang started attending Japanese elementary school. At the age of 20, he was admitted to Taiwan Sotokufu Medical School and in his first year of college, Chiang joined the Taiwan Branch of the "Chinese United Alliance" founded by Sun Yat-sen. The TCA's anthem, composed by Chiang, promoted friendship between China and Japan, Han and Japanese, and peace between Asians and white people. He saw Taiwanese people as Japanese nationals of Han Chinese ethnicity and wished to position the TCA as an intermediary between China and Japan. The TCA also aimed to "adopt a stance of national self-determination, enacting the enlightenment of the Islanders, and seeking legal extension of civil rights."[56] He told the Japanese authorities that the TCA was not a political movement and would not engage in politics.[57]

Statements aspiring to self determination and Taiwan belonging to the Taiwanese were possible at the time due to the relatively progressive era of Taishō Democracy. At the time most Taiwanese intellectuals did not wish for Taiwan to be an extension of Japan. "Taiwan is Taiwan people's Taiwan" became a common position for all anti-Japanese groups for the next decade. In December 1920, Lin Hsien-tang and 178 Taiwanese residents filed a petition to Tokyo seeking self-determination. It was rejected.[58] Taiwanese intellectuals, led by New People Society, started a movement to petition to the Japanese Diet to establish a self-governing parliament in Taiwan, and to reform the government-general. The Japanese government attempted to dissuade the population from supporting the movement, first by offering the participants membership in an advisory Consulative Council, then ordered the local governments and public schools to dismiss locals suspected of supporting the movement. The movement lasted 13 years.[59] Although unsuccessful, the movement prompted the Japanese government to introduce local assemblies in 1935.[60] Taiwan also had seats in House of Peers.[61]

The TCA had over 1,000 members composed of intellectuals, landlords, public school graduates, medical practitioners, and the gentry class. TCA branches were established across Taiwan except in indigenous areas. They gave cultural lecture tours and taught Classical Chinese as well as other more modern subjects. The TCA sought to promote vernacular Chinese language. Cultural Lecture Tours were treated as a festivity, using firecrackers traditionally used to ward off evil as a challenge against Japanese authority. If any criticism of Japan was heard, the police immediately ordered the speaker to step down. In 1923 the TCA co-founded Taiwan People's News which was published in Tokyo and then shipped to Taiwan. It was subjected to severe censorship by Japanese authorities. As many as seven or eight issues were banned. Chiang and others applied to set up an "Alliance to Urge for a Taiwan Parliament." It was deemed legal in Tokyo but illegal in Taiwan. In 1923, 99 Alliance members were arrested and 18 were tried in court. Chiang was forced to defend against the charge of "asserting 'Taiwan has 3.6 million Zhonghua Minzu/Han People' in petition leaflets."[62] Thirteen were convicted: 6 fined, 7 imprisoned (including Chiang). Chiang was imprisoned more than ten times.[63]

.svg.png.webp)

The TCA split in 1927 to form the New TCA and the Taiwanese People's Party. The TCA had been influenced by communist ideals resulting in Chiang and Lin's departure to form the Taiwan People's Party (TPP). The New TCA later became a subsidiary of the Taiwanese Communist Party, founded in Shanghai in 1928, and the only organization advocating for Taiwan's independence. The TPP's flag was designed by Chiang and drew on the Republic of China's flag for inspiration. In February 1931, the TPP was banned by the Japanese colonial government. The TCP was also banned in the same year. Chiang died from typhoid on 23 August.[65][66] However, right-leaning members such as Lin Hsien-tang, who were more cooperative with the Japanese, formed the Taiwanese Alliance for Home Rule, and the organization survived until WW2.[67]

Assimilation movement

The "early years" of Japanese administration on Taiwan typically refers to the period between the Japanese forces' first landing in May 1895 and the Tapani Incident of 1915, which marked the high point of armed resistance. During this period, popular resistance to Japanese rule was high, and the world questioned whether a non-Western nation such as Japan could effectively govern a colony of its own. An 1897 session of the Japanese Diet debated whether to sell Taiwan to France.[68] In 1898, the Meiji government of Japan appointed Count Kodama Gentarō as the fourth Governor-General, with the talented civilian politician Gotō Shinpei as his Chief of Home Affairs, establishing the carrot and stick approach towards governance that would continue for several years.[32]

Gotō Shinpei reformed the policing system, and he sought to co-opt existing traditions to expand Japanese power. Out of the Qing baojia system, he crafted the Hoko system of community control. The Hoko system eventually became the primary method by which the Japanese authorities went about all sorts of tasks from tax collecting, to opium smoking abatement, to keeping tabs on the population. Under the Hoko system, every community was broken down into Ko, groups of ten neighboring households. When a person was convicted of a serious crime, the person's entire Ko would be fined. The system only became more effective as it was integrated with the local police.[69] Under Gotō, police stations were established in every part of the island. Rural police stations took on extra duties with those in the aboriginal regions operating schools known as "savage children's educational institutes" to assimilate aboriginal children into Japanese culture. The local police station also controlled the rifles which aboriginal men relied upon for hunting as well as operated small barter stations which created small captive economies.[69]

In 1914, Itagaki Taisuke briefly led a Taiwan assimilation movement as a response to appeals from influential Taiwanese spokesmen such as the Wufeng Lin family and Lin Hsien-t'ang and his cousin. Wealthy Taiwanese made donations to the movement. In December 1914, Itagaki formally inaugurated the Taiwan Dōkakai, an assimilation society. Within a week, over 3,000 Taiwanese and 45 Japanese residents joined the society. After Itagaki left later that month, leaders of the society were arrested and its Taiwanese members detained or harassed. In January 1915, the Taiwan Dōkakai was disbanded.[70]

Japanese colonial policy sought to strictly segregate the Japanese and Taiwanese population until 1922.[71] Taiwanese students who moved to Japan for their studies were able to associate more freely with Japanese and took to Japanese ways more readily than their island counterparts. However full assimilation was rare. Even acculturated Taiwanese seem to have become more aware of their distinctiveness and island background while living in Japan.[72]

An attempt to fully Japanize the Taiwanese people was made during the kōminka period (1937–45). The reasoning was that only as fully assimilated subjects could Taiwan's inhabitants fully commit to Japan's war and national aspirations.[73] The kōminka movement was generally unsuccessful and few Taiwanese became "true Japanese" due to the short time period and large population. In terms of acculturation under controlled circumstances, it can be considered relatively effective.[74]

Status

The Japanese administration followed the Qing classification of aborigines into acculturated, (shufan), semi-acculturated (huafan), and non-acculturated aborigines (shengfan). Acculturated aborigines were treated the same as Chinese people and lost their aboriginal status. Han Chinese and shufan were both treated as natives of Taiwan by the Japanese. Below them were the semi-acculturated and non-acculturated "barbarians" who lived outside normal administrative units and upon whom government laws did not apply.[75] According to the Sōtokufu (Office of the Governor-General), although the mountain aborigines were technically humans in biological and social terms, they were animals under international law.[76]

Land rights

The Sōtokufu claimed all unreclaimed and forest land in Taiwan as government property.[77] New use of forest land was forbidden. In October 1895, the government declared that these areas belonged to the government unless claimants could provide hard documentation or evidence of ownership. No investigation into the validity of titles or survey of land were conducted until 1911. The Japanese authority denied the rights of aborigines to their property, land, and anything on the land. Although the Japanese government did not control aboriginal land directly prior to military occupation, the Han and acculturated aborigines were forbidden from any contractual relationships with aborigines.[78] The aborigines were living on government land but did not submit to government authority, and as they did not have political organization, they could not enjoy property ownership.[76] The acculturated aborigines also lost their rent holder rights under the new property laws although they were able to sell them. Some reportedly welcomed the sale of rent rights because they had difficulty collecting rent.[79]

In practice, the early years of Japanese rule were spent fighting mostly Chinese insurgents and the government took on a more conciliatory approach to the aborigines. Starting in 1903, the government implemented stricter and more coercive policies. It expanded the guard lines, previously the settler-aboriginal boundary, to restrict the aborigines' living space. By 1904 the guard lines had increased by 80 km from the end of Qing rule. Sakuma Samata launched a five-year plan for aboriginal management, which saw attacks against the aborigines and landmines and electrified fences used to force them into submission. Electrified fences were no longer necessary by 1924 due to the overwhelming government advantage.[80]

After subjugating the mountain aborigines, a small portion of land was set aside for aboriginal use. From 1919 to 1934, aborigines were relocated to areas that would not impede forest development. At first they were given a small compensation for land use but this was discontinued later on and the aborigines were forced to relinquish all claims to their land. In 1928, it was decided that each aborigine would be allotted three hectares of reserve land. Some of the allotted land was taken for forest enterprises while it was discovered that the aboriginal population was bigger than the estimated 80,000. The size of the allotted land was reduced but they were not adhered to anyways. In 1930, the government relocated aborigines to the foothills and invested in agricultural infrastructure to turn them into subsistence farmers. They were given less than half the originally promised land,[81] amounting to one-eighth of their ancestral lands.[82]

Aboriginal resistance

Aboriginal resistance to the heavy-handed Japanese policies of acculturation and pacification lasted up until the early 1930s.[45] By 1903, indigenous rebellions had resulted in the deaths of 1,900 Japanese in 1,132 incidents.[47] In 1911 a large military force invaded Taiwan's mountainous areas to gain access to timber resources. By 1915, many aboriginal villages had been destroyed. The Atayal and Bunun resisted the hardest against colonization.[83] The Bunun and Atayal were described as the "most ferocious" Aboriginals, and police stations were targeted by Aboriginals in intermittent assaults.[84]

The Bunun under Chief Raho Ari engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese for twenty years. Raho Ari's revolt, called the Taifun Incident was sparked when the Japanese implemented a gun control policy in 1914 against the Aboriginals in which their rifles were impounded in police stations when hunting expeditions were over. The revolt began at Taifun when a police platoon was slaughtered by Raho Ari's clan in 1915. A settlement holding 266 people called Tamaho was created by Raho Ari and his followers near the source of the Rōnō River and attracted more Bunun rebels to their cause. Raho Ari and his followers captured bullets and guns and slew Japanese in repeated hit and run raids against Japanese police stations by infiltrating over the Japanese "guardline" of electrified fences and police stations as they pleased.[85] As a result, head hunting and assaults on police stations by Aboriginals still continued after that year.[86][87] In one of Taiwan's southern towns nearly 5,000 to 6,000 were slaughtered by Japanese in 1915.[88]

As resistance to the long-term oppression by the Japanese government, many Taivoan people from Kōsen led the first local rebellion against Japan in July 1915, called the Jiasian Incident (Japanese: 甲仙埔事件, Hepburn: Kōsenpo jiken). This was followed by a wider rebellion from Tamai in Tainan to Kōsen in Takao in August 1915, known as the Seirai-an Incident (Japanese: 西来庵事件, Hepburn: Seirai-an jiken) in which more than 1,400 local people died or were killed by the Japanese government. Twenty-two years later, the Taivoan people struggled to carry on another rebellion; since most of the indigenous people were from Kobayashi, the resistance taking place in 1937 was named the Kobayashi Incident (Japanese: 小林事件, Hepburn: Kobayashi jiken).[89] Between 1921 and 1929 Aboriginal raids died down, but a major revival and surge in Aboriginal armed resistance erupted from 1930 to 1933 for four years during which the Musha incident occurred and Bunun carried out raids, after which armed conflict again died down.[90] The 1930 "New Flora and Silva, Volume 2" said of the mountain Aboriginals that "the majority of them live in a state of war against Japanese authority".[91]

The last major aboriginal rebellion, the Musha Incident, occurred on 27 October 1930 when the Seediq people, angry over their treatment while laboring in camphor extraction, launched the last headhunting party. Groups of Seediq warriors led by Mona Rudao attacked policed stations and the Musha Public School. Approximately 350 students, 134 Japanese, and 2 Han Chinese dressed in Japanese garbs were killed in the attack. The uprising was crushed by 2,000–3,000 Japanese troops and aboriginal auxiliaries with the help of poison gas. The armed conflict ended in December when the Seediq leaders committed suicide. According to Japanese colonial records, 564 Seediq warriors surrendered and 644 were killed or committed suicide.[92] [93] The incident caused the government to take a more conciliatory stance towards the aborigines, and during World War 2, the government tried to assimilate them as loyal subjects.[80] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the war against the aboriginals numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[94] According to a 1935 report, 7,081 Japanese were killed in the armed struggle from 1896 to 1933 while the Japanese confiscated 29,772 Aboriginal guns by 1933.[95]

Japanization

.jpg.webp)

As Japan embarked on full-scale war with China in 1937, it implemented the "kōminka" imperial Japanization project to instill the "Japanese Spirit" in Taiwanese residents, and ensure the Taiwanese would remain imperial subjects subjects (kōmin) of the Japanese Emperor rather than support a Chinese victory. The goal was to make sure the Taiwanese people did not develop a sense of "their national identity, pride, culture, language, religion, and customs".[96] To this end, the cooperation of the Taiwanese would be essential, and the Taiwanese would have to be fully assimilated as members of Japanese society. As a result, earlier social movements were banned and the Colonial Government devoted its full efforts to the "Kōminka movement" (皇民化運動, kōminka undō), aimed at fully Japanizing Taiwanese society.[32] Although the stated goal was to assimilate the Taiwanese, in practice the Kōminka hōkōkai organization that formed segregated the Japanese into their own separate block units, despite co-opting Taiwanese leaders.[97] The organization was responsible for increasing war propaganda, donation drives, and regimenting Taiwanese life during the war.[98]

As part of the kōminka policies, Chinese language sections in newspapers and Classical Chinese in the school curriculum were removed in April 1937.[73] China and Taiwan's history were also erased from the educational curriculum.[96] Chinese language use was discouraged, which reportedly increased the percentage of Japanese speakers among the Taiwanese, but the effectiveness of this policy is uncertain. Even some members of model "national language" families from well-educated Taiwanese households failed to learn Japanese to a conversational level. A name-changing campaign was launched in 1940 to replace Chinese names with Japanese ones. Seven percent of the Taiwanese had done so by the end of the war.[73] Characteristics of Taiwanese culture considered "un-Japanese" or undesirable were to be replaced with Japanese ones. Taiwanese opera, puppet plays, fireworks, and burning gold and silver paper foil at temples were banned. Chinese clothing, betel-nut chewing, and noisiness were discouraged in public. The Taiwanese were encouraged to pray at Shinto shrines and expected to have domestic altars to worship paper amulets sent from Japan. Some officials were ordered to remove religious idols and artifacts from native places of worship.[99] Funerals were supposed to conduct funerals in the modern "Japanese-style" way but it was ambiguous as to what this meant.[100]

World War II

War

As Japan embarked on full-scale war with China in 1937, it expanded Taiwan's industrial capacity to manufacture war material. By 1939, industrial production had exceeded agricultural production in Taiwan. The Imperial Japanese Navy operated heavily out of Taiwan. The "South Strike Group" was based out of the Taihoku Imperial University (now National Taiwan University) in Taiwan. Taiwan was used as a launchpad for the invasion of Guangdong in late 1938 and for the occupation of Hainan in February 1939. A joint planning and logistical center was established in Taiwan to assist Japan's southward advance after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.[102] Taiwan served as a base for Japanese naval and air attacks on the island Luzon until the surrender of the Philippines in May 1942. It also served as a rear staging ground for further attacks on Myanmar. As the war turned against Japan in 1943, Taiwan suffered due to Allied submarine attacks on Japanese shipping, and the Japanese administration prepared to be cut off from Japan. In the latter part of 1944, Taiwan's industries, ports, and military facilities were bombed in U.S. air raids.[103] By the end of the war in 1945, industrial and agricultural output had dropped far below prewar levels, with agricultural output 49% of 1937 levels and industrial output down by 33%. Coal production dropped from 200,000 metric tons to 15,000 metric tons.[104] An estimated 16,000–30,000 civilians died from the bombing.[105] By 1945, Taiwan was isolated from Japan and its government prepared to defend against an expected invasion.[103]

During WWII the Japanese authorities maintained prisoner of war camps in Taiwan. Allied prisoners of war (POW) were used as forced labor in camps throughout Taiwan with the camp serving the copper mines at Kinkaseki being especially heinous.[106] Of the 430 Allied POW deaths across all fourteen Japanese POW camps on Taiwan, the majority occurred at Kinkaseki.[107]

Military service

Starting in July 1937, Taiwanese began to play a role on the battlefield, initially in noncombatant positions. Taiwanese people were not recruited for combat until late in the war. In 1942, the Special Volunteer System was implemented, allowing even aborigines to be recruited as part of the Takasago Volunteers. From 1937 to 1945, over 207,000 Taiwanese were employed by the Japanese military. Roughly 50,000 went missing in action or died, another 2,000 were disabled, 21 were executed for war crimes, and 147 were sentenced to imprisonment for two or three years.[108]

Some Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers claim they were coerced and did not choose to join the army. Accounts range from having no way to refuse recruitment, to being incentivized by the salary, to being told that the "nation and emperor needed us."[109] In one account, a man named Chen Chunqing said he was motivated by his desire to fight the British and Americans but became disillusioned after being sent to China and tried to defect, although the effort was fruitless.[110]

Racial discrimination was commonplace despite rare occasions of camaraderie. Some experienced greater equality during their time in the military. One Taiwanese serviceman recalled being called "chankoro" (Qing slave[29]) by a Japanese soldier.[110] Some of the Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers were ambivalent about Japan's defeat and could not imagine what liberation from Japan would look like. One person recalled surrender leaflets dropped by U.S. planes stating that Taiwan would return to China and recalling that his grandfather had once told him that he was Chinese.[111]

After Japan's surrender, the Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers were abandoned by Japan and no transportation back to Taiwan or Japan was provided. Many of them faced difficulties in mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan due to anti-rightist and anti-communist campaigns in addition to accusations of taking part in the February 28 incident. In Japan they were faced with ambivalence. An organization of Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers tried to get the Japanese government to pay their unpaid wages several decades later. They failed.[112]

Comfort women

Between 1,000 and 2,000 Taiwanese women were part of the comfort women system. Aboriginal women served Japanese military personnel in the mountainous region of Taiwan. They were first recruited as housecleaning and laundry workers for soldiers, then they were coerced into providing sex. They were gang-raped and served as comfort women in the evening hours. Han Taiwanese women from low income families were also part of the comfort women system. Some were pressured into it by financial reasons while others were sold by their families.[113][114] However some women from well to do families also ended up as comfort women.[115] More than half of the young women were minors with some as young as 14. Very few women who were sent overseas understood what the true purpose of their journey was.[113] Some of the women believed they would be serving as nurses in the Japanese military prior to becoming comfort women. Taiwanese women were told to provide sexual services to the Japanese military "in the name of patriotism to the country."[115] By 1940, brothels were set up in Taiwan to service Japanese males.[113]

End of Japanese rule

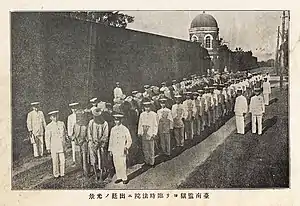

In 1942, after the United States entered the war against Japan and on the side of China, the Chinese government under the KMT renounced all treaties signed with Japan before that date and made Taiwan's return to China (as with Manchuria, ruled as the Japanese wartime puppet state of "Manchukuo") one of the wartime objectives. In the Cairo Declaration of 1943, the Allied Powers declared the return of Taiwan (including the Pescadores) to the Republic of China as one of several Allied demands. The Cairo Declaration was never signed or ratified and is not legally binding. In 1945, Japan unconditionally surrendered with the signing of the instrument of surrender and ended its rule in Taiwan as the territory was put under the administrative control of the Republic of China government in 1945 by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.[116][117] The Office of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers ordered Japanese forces in China and Taiwan to surrender to Chiang Kai-shek, who would act as the representative of the Allied Powers for accepting surrender in Taiwan. On 25 October 1945, Governor-General Rikichi Andō handed over the administration of Taiwan and the Penghu islands to the head of the Taiwan Investigation Commission, Chen Yi.[118][119] On 26 October, the government of the Republic of China declared that Taiwan had become a province of China.[120] The Allied Powers, on the other hand, did not recognize the unilateral declaration of annexation of Taiwan made by the government of the Republic of China because a peace treaty between the Allied Powers and Japan had not been concluded.[121]

Administration

As the highest colonial authority in Taiwan during the period of Japanese rule, the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan was headed by a Governor-General of Taiwan appointed by Tōkyō. Power was highly centralized with the Governor-General wielding supreme executive, legislative, and judicial power, effectively making the government a dictatorship.[32]

In its earliest incarnation, the Colonial Government was composed of three bureaus: Home Affairs, Army, and Navy. The Home Affairs Bureau was further divided into four offices: Internal Affairs, Agriculture, Finance, and Education. The Army and Navy bureaus were merged to form a single Military Affairs Bureau in 1896. Following reforms in 1898, 1901, and 1919 the Home Affairs Bureau gained three more offices: General Affairs, Judicial, and Communications. This configuration would continue until the end of colonial rule. The Japanese colonial government was responsible for building harbors and hospitals as well as constructing infrastructure like railroads and roads. By 1935 the Japanese expanded the roads by 4,456 kilometers, in comparison with the 164 kilometers that existed before the Japanese occupation. The Japanese government invested a lot of money in the sanitation system of the island. These campaigns against rats and unclean water supplies contributed to a decrease of diseases such as cholera and malaria.[122]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Under the Japanese colonial government, Taiwan was introduced to a unified system of weights and measures, a centralized bank, education facilities to increase skilled labor, farmers' associations, and other institutions. An island wide system of transportation and communications as well as facilities for travel between Japan and Taiwan were developed. Construction of large scale irrigation facilities and power plants followed. Agricultural development was the primary emphasis of Japanese colonization in Taiwan. The objective was for Taiwan to provide Japan with food and raw materials. Fertilizer and production facilities were imported from Japan. Industrial farming, electric power, chemical industries, aluminum, steel, machinery, and shipbuilding facilities were set up. Textile and paper industries were developed near the end of Japanese rule for self-sufficiency. By the 1920s modern infrastructure and amenities had become widespread, although they remained under strict government control, and Japan was managing Taiwan as a model colony. All modern and large enterprises were owned by the Japanese.[123][124]

Shortly after the cession of Taiwan to Japanese rule in September 1895, an Ōsaka bank opened a small office in Kīrun. By June of the following year the Governor-General had granted permission for the bank to establish the first Western-style banking system in Taiwan. In March 1897, the Japanese Diet passed the "Taiwan Bank Act", establishing the Bank of Taiwan (台湾銀行, Taiwan ginkō), which began operations in 1899. In addition to normal banking duties, the Bank would also be responsible for minting the currency used in Taiwan throughout Japanese rule. The function of central bank was fulfilled by the Bank of Taiwan.[125]

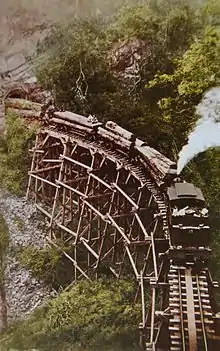

Under the governor Shimpei Goto's rule, many major public works projects were completed. The Taiwan rail system connecting the south and the north and the modernizations of Kīrun and Takao ports were completed to facilitate transport and shipping of raw material and agricultural products.[126] Exports increased by fourfold. Fifty-five percent of agricultural land was covered by dam-supported irrigation systems. Food production had increased fourfold and sugar cane production had increased 15-fold between 1895 and 1925 and Taiwan became a major foodbasket serving Japan's industrial economy. A health care system was widely established and infectious diseases were almost completely eradicated. The average lifespan for a Taiwanese resident would become 60 years by 1945.[127]

Taiwan's economy during Japanese rule was for the most part, a colonial economy. Namely, the human and natural resources of Taiwan were used to aid the development of Japan, a policy which began under Governor-General Kodama and reached its peak in 1943, in the middle of World War II. From 1900 to 1920, Taiwan's economy was dominated by the sugar industry, while from 1920 to 1930, rice was the primary export. During these two periods, the primary economic policy of the Colonial Government was "industry for Japan, agriculture for Taiwan". After 1930, due to war needs the Colonial Government began to pursue a policy of industrialization.[32]

After 1939, the war in China and eventually other places started having a deleterious effect on Taiwan's agricultural output as military conflict took up all of Japan's resources. Taiwanese real GDP per capita peaked in 1942 at $1,522 and declined to $693 by 1944.[128] War-time bombing of Taiwan caused significant damage to many cities and harbors in Taiwan. The railways, plants, and other production facilities were either badly damaged or destroyed.[129] Only 40 percent of the railroads were usable and over 200 factories were bombed, most of them housing Taiwan's vital industries. Of Taiwan's four electrical power plants, three were destroyed.[130] Loss of major industrial facilities is estimated at $506 million, or 42 percent of fixed manufacturing assets.[128] Damage to agriculture was relatively contained in comparison but most developments came to a halt and irrigation facilities were abandoned. Since all key positions were held by Japanese, their departure resulted in the loss of 20,000 technicians and 10,000 professional workers, leaving Taiwan with a severe lack of trained personnel. Inflation was rampant as a result of the war and worsened later due to economic integration with China because China was also experiencing high inflation.[129] Taiwanese industrial output recovered to 38 percent of its 1937 level by 1947 and recovery to pre-war standards of living did not occur until the 1960s.[131]

Education

A system of elementary common schools (kōgakkō) was introduced. These elementary schools taught Japanese language and culture, Classical Chinese, Confucian ethnics, and practical subjects like science.[132] Classical Chinese was included as part of the effort to win over Taiwanese upper-class parents, but the emphasis was on Japanese language and ethics.[133] These government schools served a small percentage of the Taiwanese school-age population while Japanese children attended their own separate primary schools (shōgakkō). Few Taiwanese attended secondary school or were able to enter medical college. Due to limited access to government educational institutions, a segment of the population continued to enroll in private schools similar to the Qing era. Most boys attended Chinese schools (shobo) while a smaller portion of males and females received training at religious schools (Dominican and Presbyterian). Universal education was deemed undesirable during the early years since the assimilation of Han Taiwanese seemed unlikely. Elementary education offered both moral and scientific education to those Taiwanese who could afford it. The hope was that through selective education of the brightest Taiwanese, a new generation of Taiwanese leaders responsive to reform and modernization would emerge.[132]

Many of the gentry class had mixed feelings about modernization and cultural change, especially the kind advanced by government education. The gentry was urged to promote the "new learning", a fusion of Neo-Confucianism and Meiji-style education, however those invested in the Chinese education style seemed resentful of the proposed merging.[134] A younger generation of Taiwanese more susceptible to modernization and change started participating in community affairs in the 1910s. Many were concerned about obtaining modern educational facilities and the discrimination they faced in obtaining spots at the few government schools. Local leaders in Taichung began campaigning for the inauguration of the Taichū Middle School but faced opposition from Japanese officials reluctant to authorize a middle school for Taiwanese males.[135]

In 1922, an integrated school system was introduced in which common and primary schools were opened to both Taiwanese and Japanese based on their background in spoken Japanese.[136] Elementary education was divided between primary schools for Japanese speakers and public schools for Taiwanese speakers. Since few Taiwanese children could speak fluent Japanese, in practice only the children of very wealthy Taiwanese families with close ties to Japanese settlers were allowed study alongside Japanese children.[137] The number of Taiwanese at formerly Japanese-only elementary schools was limited to 10 percent.[133] Japanese children also attended kindergarten, during which they were segregated from Taiwanese children. In one instance a Japanese-speaking child was put in the Taiwanese group with the expectation that they would learn Japanese from her, but the experiment failed and the Japanese-speaking child learned Taiwanese instead.[137]

The competitive situation in Taiwan made some Taiwanese seek secondary education and opportunities in Japan and Manchukuo rather than Taiwan.[133] In 1943, primary education became compulsory, and by the next year nearly three out of four children were enrolled in primary school.[138] Taiwanese also studied in Japan. By 1922 at least 2,000 Taiwanese were enrolled in educational institutions in metropolitan Japan. The number increased to 7,000 by 1942.[72] By 1944, there were 944 primary schools in Taiwan with total enrollment rates of 71.3% for Taiwanese children, 86.4% for aboriginal children, and 99.6% for Japanese children in Taiwan. As a result, primary school enrollment rates in Taiwan were among the highest in Asia, second only to Japan itself.[32]

Demographics

As part of the emphasis placed on governmental control, the Colonial Government performed detailed censuses of Taiwan every five years starting in 1905. Statistics showed a population growth rate of 0.988 to 2.835% per year throughout Japanese rule. In 1905, the population of Taiwan was roughly 3 million.[139] By 1940 the population had grown to 5.87 million, and by the end of World War II in 1946 it numbered 6.09 million. As of 1938, around 309,000 people of Japanese origin lived in Taiwan.[140]

Aboriginals

According to the 1905 census, the aboriginal population included 45,000+ plains aborigines who were almost completely assimilated into Han Chinese society, and 113,000+ mountain aborigines.[141]

Overseas Chinese

The Consulate-General of the Republic of China in Taihoku was a diplomatic mission of the government of the Republic of China (ROC) that opened April 6, 1931, and closed in 1945 after the handover of Taiwan to the ROC. Even after Taiwan had been ceded to Japan by the Qing dynasty, it still attracted over 20,000 Chinese immigrants by the 1920s. On May 17, 1930, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs appointed Lin Shao-nan to be the Consul-General[142] and Yuan Chia-ta as Deputy Consul-General.

Japanese colonists

Japanese commoners started arriving in Taiwan in April 1896.[143] Japanese migrants were encouraged to move to Taiwan because it was considered the most effective way of integrating Taiwan into the Japanese Empire. Few Japanese moved to Taiwan during the colony's early years due to poor infrastructure, instability, and fear of disease. Later on as more Japanese settled in Taiwan, some settlers came to view the island as their homeland rather than Japan. There was concern that Japanese children born in Taiwan, under its tropical climate, would not be able to understand Japan. In the 1910s, primary schools conducted trips to Japan to nurture their Japanese identity and to prevent Taiwanization. Out of necessity, Japanese police officers were encouraged to learn the local variants of Minnan and the Guangdong dialect of Hakka. There were language examinations for police officers to receive allowances and promotions.[137] By the late 1930s, Japanese people made up about 5.4 percent of Taiwan's total population but owned 20–25 percent of the cultivated land which was also of higher quality. They also owned the majority of large land holdings. The Japanese government assisted them in acquiring land and coerced Chinese land owners to sell to Japanese enterprises. Japanese sugar companies owned 8.2 percent of the arable land.[144]

At the end of the Second World War, there were almost 350,000 Japanese civilians living in Taiwan. They were designated as Overseas Japanese (Nikkyō) or as Overseas Ryukyuans (Ryūkyō).[145] Offspring of intermarriage were considered Japanese if their Taiwanese mother chose Japanese citizenship or if their Taiwanese father did not apply for ROC citizenship.[146] As many as half the Japanese who left Taiwan after 1945 were born in Taiwan.[145] The Taiwanese did not engage in widespread acts of revenge or push for their immediate removal, although they quickly seized or attempted to occupy property they believed were unfairly obtained in previous decades.[147] Japanese assets were collected and the Nationalist government retained most of the properties for government use, to the consternation of the Taiwanese.[148] Theft and acts of violence did occur, however this has been attributed to the pressure of wartime policies.[147] Chen Yi, who was in charge of Taiwan, removed Japanese bureaucrats and police officers from their posts, resulting in unaccustomed economic hardship for Japanese citizens. Their hardship in Taiwan was also met by news of hardship in Japan. A survey found that 180,000 Japanese civilians wished to leave for Japan while 140,000 wished to stay. An order for the deportation of Japanese civilians was issued in January 1946.[149] From February to May, the vast majority of Japanese left Taiwan and arrived in Japan without much trouble. Overseas Ryukyuans were ordered to assist the deportation process by building camps and work as porters for the Overseas Japanese. Each person was allowed to leave with two pieces of luggage and 1,000 yen.[150] The Japanese and Ryukyuans remaining in Taiwan by the end of April did so at the behest of the government. Their children attended Japanese schools to prepare for life in Japan.[151]

Social policy

"Three Vices"

The "Three Vices" (三大陋習, Santai rōshū) considered by the Office of the Governor-General to be archaic and unhealthy were the use of opium, foot binding, and the wearing of queues.[152][153]

In 1921, the Taiwanese People's Party accused colonial authorities before the League of Nations of being complicit in the addiction of over 40,000 people, while making a profit off opium sales. To avoid controversy, the Colonial Government issued the New Taiwan Opium Edict on December 28, and related details of the new policy on January 8 of the following year. Under the new laws, the number of opium permits issued was decreased, a rehabilitation clinic was opened in Taihoku, and a concerted anti-drug campaign launched.[154] Despite the directive, the government remained involved with the opium trade until June 1945.[155]

Literature

Taiwanese students studying in Tōkyō first restructured the Enlightenment Society in 1918, later renamed the New People Society (新民会, Shinminkai) after 1920. This was the manifestation for various upcoming political and social movements in Taiwan. Many new publications, such as Taiwanese Literature & Art (1934) and New Taiwanese Literature (1935), started shortly thereafter. These led to the onset of the vernacular movement in society at large as the modern literary movement broke away from the classical forms of ancient poetry. In 1915, this group of people, led by Rin Kendō, made an initial and large financial contribution to establish the first middle school in Taichū for the aboriginals and Taiwanese.[156]

Literature movements did not disappear even when they were under censorship by the colonial government. In the early 1930s, a famous debate on Taiwanese rural language unfolded formally. This event had numerous lasting effects on Taiwanese literature, language and racial consciousness. In 1930, Taiwanese-Japanese resident Kō Sekiki (黄 石輝, Huáng Shíhuī) started the debate on rural literature in Tōkyō. He advocated that Taiwanese literature should be about Taiwan, have impact on a wide audience, and use Taiwanese Hokkien. In 1931, Kaku Shūsei (郭秋生, Guō Qiūshēng), a resident of Taihoku, prominently supported Kō's viewpoint. Kaku started the Taiwanese Rural Language Debate, which advocated literature published in Taiwanese. This was immediately supported by Rai Wa (頼 和, Lài Hé), who is considered as the father of Taiwanese literature. After this, dispute as to whether the literature of Taiwan should use Taiwanese or Chinese, and whether the subject matter should concern Taiwan, became the focus of the New Taiwan Literature Movement. However, because of the upcoming war and the pervasive Japanese cultural education, these debates could not develop any further. They finally lost traction under the Japanization policy set by the government.[157]

Taiwanese literature mainly focused on the Taiwanese spirit and the essence of Taiwanese culture. People in literature and the arts began to think about issues of Taiwanese culture, and attempted to establish a culture that truly belonged to Taiwan. The significant cultural movement throughout the colonial period were led by the young generation who were highly educated in formal Japanese schools. Education played such a key role in supporting the government and to a larger extent, developing economic growth of Taiwan. However, despite the government prime effort in elementary education and normal education, there was a limited number of middle schools, approximately 3 across the whole country, so the preferred choices for graduates were leaving for Tōkyō or other cities to get an education. The foreign education of the young students was carried out solely by individuals' self-motivation and support from family. Education abroad got its popularity, particularly from Taichū prefecture, with the endeavor for acquiring skills and knowledge of civilization even under the situation of neither the colonial government nor society being able to guarantee their bright future; with no job plan for these educated people after their return.[158]

Change of governing authority

Japan surrendered to the Allies on August 14, 1945. On August 29, Chiang Kai-shek appointed Chen Yi as Chief Executive of Taiwan Province, and announced the creation of the Office of the Chief Executive of Taiwan Province and Taiwan Garrison Command on September 1, with Chen Yi also as the commander of the latter body. After several days of preparation, an advance party moved into Taihoku on October 5, with more personnel from Shanghai and Chongqing arriving between October 5 and 24. By 1938 about 309,000 Japanese lived in Taiwan.[140] Between the Japanese surrender of Taiwan in 1945 and April 25, 1946, the Republic of China forces repatriated 90% of the Japanese living in Taiwan to Japan.[159]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- "FORMOSA EXAMINES TRIO.; Gates, American Prisoner, and Two Others Taken to Giran". The New York Times. May 6, 1935. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Pastreich, Emanuel (July 2003). "Sovereignty, Wealth, Culture, and Technology: Mainland China and Taiwan Grapple with the Parameters of "Nation State" in the 21st Century". Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. OCLC 859917872. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Eckhardt, Jappe; Fang, Jennifer; Lee, Kelley (March 4, 2017). "The Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation: To 'join the ranks of global companies'". Global Public Health. 12 (3): 335–350. doi:10.1080/17441692.2016.1273366. ISSN 1744-1692. PMC 5553428. PMID 28139964.

- Chen, C. Peter. "Japan's Surrender". World War II Database. Lava Development, LLC. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Huang, Fu-san (2005). "Chapter 3". A Brief History of Taiwan. ROC Government Information Office. Archived from the original on August 1, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- Wills (2006).

- Smits, Gregory (2007). "Recent Trends in Scholarship on the History of Ryukyu's Relations with China and Japan" (PDF). In Ölschleger, Hans Dieter (ed.). Theories and Methods in Japanese Studies: Current State and Future Developments (Papers in Honor of Josef Kreiner). Göttingen: Bonn University Press via V&R Unipress. pp. 215–228. ISBN 978-3-89971-355-8.

- Frei, Henry P., Japan's Southward Advance and Australia, Univ of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, ç1991. p.34 - "...ordered the Governor of Nagasaki, Murayama Toan, to invade Formosa with a fleet of thirteen vessels and around 4000 men. Only a hurricane thwarted this effort and forced their early return"

- Andrade 2008b.

- Andrade 2008c.

- Wong 2017, p. 116.

- Barclay 2018, p. 50.

- Barclay 2018, p. 51-52.

- Barclay 2018, p. 52.

- Barclay 2018, p. 53–54.

- Wong 2022, p. 124–126.

- Leung (1983), p. 270.

- Wong 2022, p. 127–128.

- Zhao, Jiaying (1994). 中国近代外交史 [A Diplomatic History of China] (in Chinese) (1st ed.). Taiyuan: 山西高校联合出版社. ISBN 9787810325776.

- Wong 2022, p. 132.

- Wong 2022, p. 134–137.

- Wong 2022, p. 130.

- Wong 2022, p. 137–138.

- Wong 2022, p. 141–143.

- Chen, Edward I-te (November 1977). "Japan's Decision to Annex Taiwan: A Study of Ito-Mutsu Diplomacy, 1894–95". The Journal of Asian Studies. 37 (1): 66–67. doi:10.2307/2053328. JSTOR 2053328. S2CID 162461372.

- A detailed account of the transference of Taiwan, translated from the Japan Mail, appears in Davidson (1903), pp. 293–295

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 203.

- Chen (1977), pp. 71–72 argues that Itō and Mutsu wanted Japan to gain equality with the Western powers. Japan's decision to annex Taiwan was not based on any long-range design for future aggression.

- Shih 2022, p. 327.

- Ching, Leo T. S. (2001). Becoming "Japanese": Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 0-520-22553-8.

- Davidson (1903), p. 293.

- Huang, Fu-san (2005). "Chapter 6: Colonization and Modernization under Japanese Rule (1895–1945)". A Brief History of Taiwan. ROC Government Information Office. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 205–206.

- Morris (2002), pp. 4–18.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 207.

- Wang 2006, p. 95.

- Davidson 1903, p. 561.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 208.

- Brooks 2000, p. 110.

- Dawley, Evan. "Was Taiwan Ever Really a Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- Zhang (1998), p. 515.

- Chang 2003, p. 56.

- "Taiwan – History". Windows on Asia. Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 207–208.

- Katz (2005).

- Zhang (1998), p. 514.

- Price 2019, p. 115.

- Sir Adolphus William Ward; George Walter Prothero; Sir Stanley Mordaunt Leathes; Ernest Alfred Benians (1910). The Cambridge Modern History. Macmillan. pp. 573–.

- Huang-wen lai (2015). "The turtle woman's voices: Multilingual strategies of resistance and assimilation in Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule" (pdf published=2007). p. 113. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- Lesser Dragons: Minority Peoples of China. Reaktion Books. May 15, 2018. ISBN 9781780239521.

- Place and Spirit in Taiwan: Tudi Gong in the Stories, Strategies and Memories of Everyday Life. Routledge. August 29, 2003. ISBN 9781135790394.

- Tsai 2009, p. 134.

- Wang 2000, p. 113.

- Su 1980, p. 447–448.

- "Governmentality and Its Consequences in Colonial Taiwan: A Case Study of the Ta-pa-ni Incident" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2007.

- Shih 2022, p. 329.

- Shih 2022, p. 330.

- Shih 2022, p. 330–331.

- I-te chen, Edward (1972). "Formosan Political Movements Under Japanese Colonial Rule, 1914-1937". The Journal of Asian Studies. 31 (3): 477–497. doi:10.2307/2052230. JSTOR 2052230. S2CID 154679070.

- "戦間期台湾地方選挙に関する考察". 古市利雄. 台湾研究フォーラム 【台湾研究論壇】. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- Yeh, Lindy (April 15, 2002). "The Koo family: a century in Taiwan". Taipei Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Shih 2022, p. 331–333.

- Shih 2022, p. 333.

- 蔣渭水最後的驚嘆號-崇隆大眾葬紀錄時代心情, 蔣渭水文化基金會

- Shih 2022, p. 335–336.

- "台灣大百科橫". nrch.culture.tw (in Chinese). Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- "三、臺人政治運動的興起與分裂(三) | 中央研究院臺灣史研究所檔案館 - 臺灣歷史檔案資源網". Archived from the original on December 23, 2022. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- Shaohua Hu (2018). Foreign Policies toward Taiwan. Routledge. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-1-138-06174-3. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- Crook, Steven (December 4, 2020). "Highways and Byways: Handcuffed to the past". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 219.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 220–221.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 230.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 240.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 242.

- Ye 2019, p. 189–190.

- Ye 2019, p. 192.

- Ye 2019, p. 183.

- Ye 2019, p. 191.

- Ye 2019, p. 195–197.

- Ye 2019, p. 193.

- Ye 2019, p. 204–205.

- Ye 2019, p. 1.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 211–212.

- The Japan Year Book 1937 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 1004.

- Crook 2014 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 16.

- The Japan Year Book 1937 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 1004.

- ed. Inahara 1937, p. 1004.

- Tay-sheng Wang (April 28, 2015). Legal Reform in Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule, 1895–1945: The Reception of Western Law. University of Washington Press. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-295-80388-3. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- 種回小林村的記憶 : 大武壠民族植物暨部落傳承400年人文誌 (A 400-Year Memory of Xiaolin Taivoan: Their Botany, Their History, and Their People). Kaohsiung City: 高雄市杉林區日光小林社區發展協會 (Sunrise Xiaolin Community Development Association). 2017. ISBN 978-986-95852-0-0.

- ed. Lin 1995 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 84.

- ed. Cox 1930 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 94.

- Matsuda 2019, p. 106.

- Ching (2001), pp. 137–140.

- The Japan Year Book 1933, p. 1139.

- Japan's progress number ... July 1935 Archived February 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 19.

- Chen 2001, p. 181.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 238–239.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 239.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 241-242.

- Tainaka, Chizuru (2020). "The "improvement of funeral ceremonies" movement and the creation of "modern" Japanese subjects in Taiwan during Japanese rule". Contemporary Japan. 32 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1080/18692729.2019.1709137. S2CID 214156519.

- Yuan-Ming Chiao (August 21, 2015). "I was fighting for Japanese motherland: Lee". The China Post. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 235.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 235–236.

- "歷史與發展 (History and Development)". Taipower Corporation. Archived from the original on May 14, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- Economic Development of Emerging East Asia: Catching up of Taiwan and South Korea. Anthem Press. September 27, 2017. ISBN 9781783086887.

- Sui, Cindy (June 15, 2021). "WW2: Unearthing Taiwan's forgotten prisoner of war camps". BBC News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- Prentice, David (October 30, 2015). "The Forgotten POWs of the Pacific: The Story of Taiwan's Camps". Thinking Taiwan. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Chen 2001, p. 182.

- Chen 2001, p. 183–184.

- Chen 2001, p. 186–187.

- Chen 2001, p. 188–189.

- Chen 2001, p. 192–195.

- Ward 2018, p. 2–4.

- William Logan; Keir Reeves (December 5, 2008). Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with 'Difficult Heritage'. Routledge. pp. 124–. ISBN 978-1-134-05149-6. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- "The Origins and Implementation of the Comfort Women System". December 14, 2018.

- "UNHCR | Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Taiwan: Overview". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2010. UNHCR

- Lowther, William (June 9, 2013). "CIA report shows Taiwan concerns". Taipei Times. p. 1. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

[Quoting from a declassified CIA report on Taiwan written in March 1949] From the legal standpoint, Taiwan is not part of the Republic of China. Pending a Japanese peace treaty, the island remains occupied territory in which the US has proprietary interests.

- Tsai 2009, p. 173.

- Henckaerts, Jean-Marie (1996). The international status of Taiwan in the new world order: legal and political considerations. Kluwer Law International. p. 337. ISBN 90-411-0929-3.

p7. "In any case, there appears to be strong legal ground to support the view that since the entry into force of the 1952 ROC-Japan bilateral peace treaty, Taiwan has become the de jure territory of the ROC. This interpretation of the legal status of Taiwan is confirmed by several Japanese court decisions. For instance, in the case of Japan v. Lai Chin Jung, decided by the Tokyo High Court on December 24, 1956, it was stated that 'Formosa and the Pescadores came to belong to the Republic of China, at any rate on August 5, 1952, when the [Peace] Treaty between Japan and the Republic of China came into force…'"

p8. "the principles of prescription and occupation that may justify the ROC's claim to Taiwan certainly are not applicable to the PRC because the application of these two principles to the Taiwan situation presupposes the validity of the two peace treaties by which Japan renounce its claim to Taiwan and thus makes the island terra nullius." - Henckaerts, Jean-Marie (1996). The international status of Taiwan in the new world order: legal and political considerations. Kluwer Law International. p. 337. ISBN 90-411-0929-3.

p4. "On October 25, 1945, the government of the Republic of China took over Taiwan and the P'eng-hu Islands from the Japanese and on the next day announced that Taiwan had become a province of China."

- CIA (March 14, 1949). "Probable Developments in Taiwan" (PDF). pp. 1–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

From the legal standpoint, Taiwan is not part of the Republic of China. Pending a Japanese peace treaty, the island remains occupied territory......neither the US, or any other power, has formally recognized the annexation by China of Taiwan......

- Roy, Denny (2003). Taiwan : a political history (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8014-8805-4.

- Shih 1968, p. 115-116.

- van der Wees, Gerrit. "Has Taiwan Always Been Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- Mark Metzler (March 13, 2006). Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan. University of California Press. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-0-520-93179-4. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- Takekoshi (1907).

- Kerr (1966).