Edrophonium

Edrophonium is a readily reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. It prevents breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and acts by competitively inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, mainly at the neuromuscular junction. It is sold under the trade names Tensilon and Enlon (according to FDA Orange Book).

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tensilon |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | FDA Professional Drug Information |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H16NO+ |

| Molar mass | 166.244 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Clinical uses

Edrophonium (by the so-called Tensilon test) is used to differentiate myasthenia gravis from cholinergic crisis and Lambert-Eaton. In myasthenia gravis, the body produces autoantibodies which block, inhibit or destroy nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the neuromuscular junction. Edrophonium—an effective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor—will reduce the muscle weakness by blocking the enzymatic effect of acetylcholinesterase enzymes, prolonging the presence of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft. It binds to a Serine-103 allosteric site, while pyridostigmine and neostigmine bind to the AchE active site for their inhibitory effects. In a cholinergic crisis, where a person has too much neuromuscular stimulation, edrophonium will make the muscle weakness worse by inducing a depolarizing block. However, the edrophonium and ice pack tests are no longer recommended as first-line tests due to false positive results. In practice, the edrophonium test has been replaced by testing for autoantibodies, including acetylcholine receptor (AchR) autoantibodies and muscle specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) autoantibodies.[1][2]

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), is similar to myasthenia gravis in that it is an autoimmune disease. However, in LEMS the neuron is unable to release enough acetylcholine for normal muscle function due to autoantibodies attacking P/Q-type calcium channel that are necessary for acetylcholine release. This means there is insufficient calcium ion influx into presynaptic terminal resulting in reduced exocytosis of acetylcholine containing vesicles. Consequently, there will typically be not as much increase in muscle strength observed after edrophonium injection, if any with LEMS.

The Tensilon test may also be used to predict if neurotoxic paralysis caused by snake envenomation is presynaptic or postsynaptic. If it is a postsynaptic then paralysis will be temporally reversed, indicating that can be reversed by adequate antivenom therapy. If the neurotoxic is presynaptic then the Tensilon test will show no response and antivenom will not reverse such paralysis. In this instance reversal of paralysis will not occur until the damaged terminal axons at the neuromuscular junction have recovered, this may take days or weeks.[3]

The drug may also be used for reversal of neuromuscular blockade at the end of a surgical procedure.[4]

Chemistry

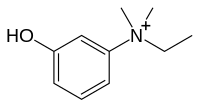

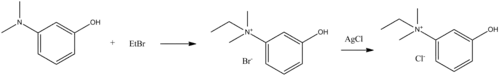

Edrophonium, ethyl-(3-hydroxyphenyl)dimethylammonium chloride, is made by reacting 3-dimethylaminophenol with ethyl bromide, which forms ethyl(3-hydroxyphenyl)dimethylammonium bromide, the bromine atom of which is replaced with a chlorine atom by reacting it with silver chloride, giving edrophonium.[5]

Pharmacokinetics

The drug has a brief duration of action, about 10–30 mins.[4]

References

- Meriggioli MN, Sanders DB (July 2012). "Muscle autoantibodies in myasthenia gravis: beyond diagnosis?". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 8 (5): 427–438. doi:10.1586/eci.12.34. PMC 3505488. PMID 22882218.

- Caliandro P, Evoli A, Stålberg E, Granata G, Tonali P, Padua L (December 2009). "The difficulty in confirming clinical diagnosis of myasthenia gravis in a seronegative patient: a possible neurophysiological approach". Neuromuscular Disorders. 19 (12): 825–827. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2009.09.005. PMID 19846306. S2CID 25219973.

- Cameron P, Jelinek G, Everitt I, Browne G, Raftos J (September 2011). Textbook of Paediatric Emergency (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 443–4. ISBN 978-0-7020-5636-9.

- Tripati KD (2004). Essentials of Medical Pharmacology (5th ed.). Jaypee Brothers Medical. p. 84. ISBN 978-81-8061-187-2.

- US 2647924, Aeschlimann JA, Stempel A, issued 1953