Teuta

Teuta (Illyrian: *Teutana, 'mistress of the people, queen'; Ancient Greek: Τεύτα; Latin: Teuta) was the queen regent[A] of the Ardiaei tribe in Illyria,[1] who reigned approximately from 231 BC to 228/227 BC.[2][3]

| Teuta | |

|---|---|

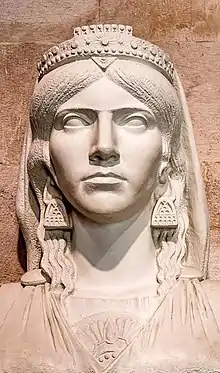

Modern bust of Teuta from the Skanderbeg Museum in Kruja | |

| Queen regent[A] of the Ardiaean | |

| Regency | 231–228/227 BC |

| Predecessor | Agron of Illyria |

| Successor | Demetrius of Pharos |

| Monarch | Pinnes |

| Spouse | Agron |

| House | Ardiaei |

| Dynasty | Ardiaean |

Following the death of her spouse Agron in 231 BC, she assumed the regency of the Ardiaean Kingdom for her stepson Pinnes, continuing Agron's policy of expansion in the Adriatic Sea, in the context of an ongoing conflict with the Roman Republic regarding the effects of Illyrian piracy on regional trade.[4][2] The death of one of the Roman ambassadors at the hands of Illyrian pirates gave Rome the occasion to declare war against her in 229 BC. She surrendered after losing the First Illyrian War in 228. Teuta had to relinquish the southern parts of her territory and pay a tribute to Rome, but was eventually allowed to keep a realm confined to an area north of Lissus (modern Lezhë).[5][2]

Biographical details on the life of Teuta are biased by the fact that surviving ancient sources, which were written by Greek and Roman authors, are generally hostile to Illyrians and their queen alike for political or misogynistic reasons.[6][7][3]

Name

Her name is known in Ancient Greek as Τεύτα (Teúta) and in Latin as Teuta, both used as a diminutive form of the Illyrian name Teuta(na) ('queen'; literally 'mistress of the people').[8] It descends from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stem *teutéh₁- ('the people', perhaps 'the people under arms'),[B] attached to the PIE suffix -nā ('mistress of'; masc. -nos).[9] The Illyrian name Teuta(na) is cognate with the Gothic masculine form þiudans 'king' (derived from an earlier *teuto-nos 'master of the people').[10][11]

Biography

Background

After the death of her husband Agron (250–231 BC),[12] the former king of the Ardiaei, she inherited his kingdom and acted as regent for her young stepson Pinnes.[13] The exact extent of the kingdom of Agron and Teuta remains uncertain.[14] From what we know, it stretched on the Adriatic coast-land from central Albania up to the Neretva river,[2] and they must have controlled most of the Illyrian inland.[14] According to Polybius, Teuta soon addressed the neighbouring states malevolently, ordering her commanders to treat all of them as enemies and supporting the piratical raids of her subjects, which eventually brought Roman forces to cross the Adriatic for the first time, since those activities increasingly interfered with their trade route in the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea.[6][2][3]

Early reign (231–230 BC)

In 231 BC, Teuta's armies attacked the regions of Elis and Messenia in the Peloponnese. On their way home, they captured the Epirote city of Phoenice, at that time the most prosperous place of Epirus and a centre for the growing commerce with the Italian Peninsula. The city was soon liberated and a truce accepted against the payment of a fee and freeborn prisoners.[15] The seizure of an urban centre, as opposed to looting in the countryside, represented an escalation in the threat posed by Illyrians to Greeks and Romans alike.[6] During their occupation of Phoenice, some Illyrian pirates looted Italian merchant ships in such a high number that the Roman Senate, after ignoring earlier complaints, was compelled to dispatch ambassadors to the city of Scodra in order to solicit reparations and demand an end to all pirate expeditions.[6] The vivid account of the event, given by the Greek historian Polybius and overtly hostile to Teuta, was probably influenced by an earlier Roman tradition originally intended to justify the invasion of Illyria.[6][7]

On their arrival, the Roman ambassadors found Queen Teuta celebrating the end of an internal Illyrian rebellion as her armies were about to lay siege to the Greek island city of Issa.[6] She promised that no royal force would hurt them, but that piracy was a traditional Illyrian custom she was unable to put an end to.[6] Teuta also implied that "it was contrary to the custom of the Illyrian kings to hinder their subjects from winning booty from the sea".[16] One of the envoys reportedly lost his temper and replied that Rome would make it her business to "improve relations between sovereign and subject in lllyria",[17] since "[they had] an admirable custom, which is to punish publicly the doers of private wrongs and publicly come to the help of the wronged."[18]

The ambassador expressed himself to the queen so disrespectfully that her attendants were ordered to seize their ship as it embarked back for Rome, and the insolent envoy was murdered on his homeward voyage, allegedly on Teuta's order.[17][3] In Polybius' account, the Roman ambassadors are named Gaius and Lucius Coruncanius.[6] Cassius Dio's account suggests that they were more than two ambassadors, and that some of them were murdered while others were made prisoners.[19] In Appian's version, the two ambassadors, one Roman (Coruncanius) and one Issaian (Kleemporos), were captured and murdered by some Illyrian lemboi before they landed on Illyrian land while Agron was still alive, implying that the interview between Teuta and the ambassadors may not have occurred.[20][21] In any case, news of the murder caused the Romans to prepare for war: legions were enlisted and the fleet assembled.[17]

War with Rome (229–228 BC)

In 229 BC, Rome declared war on Illyria and, for the first time, the Roman armies crossed the Adriatic Sea to set foot in the western Balkans.[22] An army consisting of approximately 20,000 troops, 200 cavalry units and an entire Roman fleet of 200 ships, led by Gnaeus Fulvius Centumalus and Lucius Postumius Albinus, was sent to conquer Illyria.[3]

The Roman attack seems to have caught up Teuta by surprise, since she had ordered a large naval expedition involving most of her ships against the Greek colony of Corcyra in the winter of 229. When the 200 Roman ships showed up at Corcyra, Teuta's governor Demetrius betrayed her and surrendered the city to the Romans, before turning into their advisor for the remaining time of the war.[23][17][3] At the end of the conflict in 228 BC, the Romans awarded him the position of governor of Pharos and the adjacent coasts.[23] In the meantime, the remainder of the Roman army landed further north at Apollonia.[23] The combined army and navy proceeded northward together. After subduing one town after another, they eventually besieged the capital, Scodra.[23] Teuta herself had retreated with a few followers to the fortified and strategically well-placed city of Rhizon, the principal base of the Illyrian fleet.[23][3]

According to Polybius, she made a treaty in the early spring of 228 BC by which she consented to pay an annual tribute, to reign over a restricted and narrow region north of Lissus (modern Lezhë), and not to sail beyond Lissus with more than two unarmed ships.[2][3] He also reports that they required her to acknowledge the final authority of Rome.[5][2] According to Cassius Dio, she abdicated later in 227 BC.[24][2][3]

Later life

Appian mentions that, after the defeat, Teuta sent an embassy to Rome to deliver captives and to apologize for the events that had occurred during her spouse Agron's reign, but not under hers.[3]

Ancient depictions

Reliability of accounts

The most detailed account of Teuta's short reign is that of Polybius (c. 200–118 BC), supplemented by Appian (2nd c. AD) and Cassius Dio (c. 155–235 AD).[3] According to scholar Marjeta Šašel Kos, the most objective portrait of Teuta is that of Appian.[3] Historian Peter Derow also argues that Appian's version, especially the story of the murder of the ambassadors, is more plausible than that of Polybius.[25]

Polybius' narrative, written almost one century after the events and generally hostile to Illyrians and their queen alike, was probably inherited from an earlier account written by the Roman historian Quintus Fabius Pictor (fl. 200 BC), a contemporary of Teuta who was strongly biased towards his own nation.[26][7] But if Polybius was ready to accept the negative picture of the existing tradition, as it confirmed his own negative views on women, he was also aware of Fabius' own prejudices and opposed them on some occasions.[7]

Misogyny

In his Histories, Polybius opens the story of the reign of Teuta in those terms: "[Agron] was succeeded on the throne by his wife Teuta, who left the details of administration to friends on whom she relied. As, with a woman's natural shortness of view, she could see nothing but the recent success and had no eyes for what was going on elsewhere..."[27]

The misogyny of Cassius Dio is also evident in his portrait of Teuta. He describes the Illyrian queen as follows: "...woman-like, in addition to her innate recklessness, she was puffed up with vanity because of the power that she possessed ... In a very short time, however, she demonstrated the weakness of the female sex, which quickly flies into a passion through lack of judgment, and quickly becomes terrified through cowardice."[28]

Modern legend

According to a legend with its roots in the town of Risan, Teuta ended her life in grief by throwing herself from Orjen mountains at Lipci.[29]

Legacy

Teuta is a common given name among modern Albanian women.[30] The Albanian sporting club Teuta Durrës was named after her in 1930.[31]

References

- Polybius 2010: 2:4:6: "King Agron (...) was succeeded on the throne by his wife Teuta..."; Wilkes 1992, pp. 80, 129, 167.

- Elsie 2015, p. 3.

- Šašel Kos 2012.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 158.

- Derow 2016.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 159.

- Eckstein 1995, p. 154.

- Boardman & Sollberger 1982, pp. 869–870; Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 288; Wilkes 1992, p. 72; West 2007, p. 137; De Simone 2017, p. 1869

- Boardman & Sollberger 1982, pp. 869–870; Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 288; West 2007, p. 137

- Boardman & Sollberger 1982, pp. 869–870.

- West 2007, p. 137.

- Hammond 1993, p. 105.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 167.

- Berranger, Cabanes & Berranger-Auserve 2007, p. 136.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 158–159.

- Polybius 2010, 2:8:9.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 160.

- Polybius 2010, 2:8:11.

- Cassius Dio 1914, 12, Zonaras 8, 19.

- Derow 1973, p. 119.

- Appian 2019, 9:2:18–19.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 159–160.

- Ceka 2013, p. 180.

- Cassius Dio 1914, 12 fr. 49.7.

- Derow 1973, p. 128.

- Derow 1973, pp. 123, 129.

- Polybius 2010, 2:4:6–2:4:8.

- Cassius Dio 1914, 12, Zonaras 8, 18.

- Dyczek 2009, p. 189.

- Elsie 2010, p. 439.

- Rohr, Bernd (2011). Fußball-Lexikon. Stiebner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7679-1132-1.

Footnotes

Primary sources

- Appian (2019). Roman History, Volume II. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by McGing, Brian. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99648-9.

- Cassius Dio (1914). Roman History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Cary, Earnest; Foster, Herbert B. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99041-8.

- Polybius (2010). The Histories. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Paton, W. R.; Walbank, F. W.; Habicht, Christian. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99637-3.

Bibliography

- Berranger, Danièle; Cabanes, Pierre; Berranger-Auserve, Danièle (2007). Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: Mélanges offerts au Professeur Pierre Cabanes. Presses Universitaire Blaise Pascal. ISBN 978-2845163515.

- Boardman, John; Sollberger, E. (1982). J. Boardman; I. E. S. Edwards; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. Vol. III (part 1) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521224969.

- Ceka, Neritan (2013). The Illyrians to the Albanians. Migjeni.

- Derow, Peter S. (1973). "Kleemporos". Phoenix. 27 (2): 118–134. doi:10.2307/1087485. ISSN 0031-8299. JSTOR 1087485.

- Derow, Peter S. (2016). "Teuta". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6310. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

- De Simone, Carlo (2017). "Illyrian". In Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 3. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-054243-1.

- Dyczek, Piotr (2009). "Rock Art from Lipci, Montenegro". Dacia. Académie de la Republique Populaire Roumaine. Institutul de Archéologie. 52: 189–197.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (1995). Moral Vision in the Histories of Polybius. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91469-8.

- Elsie, Robert (2015). "The Early History of Albania" (PDF). Keeping an Eye on the Albanians: Selected Writings in the Field of Albanian Studies. Albanian Studies. Vol. 16. ISBN 978-1-5141-5726-8.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6188-6.

- Hammond, Nicholas G. L. (1993). Studies concerning Epirus and Macedonia before Alexander. Hakkert. ISBN 9789025610500.

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. (EIEC).

- Šašel Kos, Marjeta (2012), "Teuta, Illyrian queen", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Wiley-Blackwell, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah09233, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6

- West, Martin L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- Wilkes, John (1992). The Illyrians. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631198075.

Further reading

- Jackson-Laufer, Guida Myrl (1999). Women Rulers throughout the Ages: An Illustrated Guide. New York: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 1576070913.

- Jones, David E. (2000). Women Warriors: A History. Brassey's. ISBN 9781574882063.

- Grant DePauw, Linda (2000). Battle Cries and Lullabies: Women in War from Prehistory to the Present. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806132884.

- Meijer, Fik (1986). A History of Seafaring in the Classical World. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312000758.

- Prodanović, Nada Ćurčija; Ristić, Dus̆an (1973). Teuta, Queen of Illyria. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192713531.

- Walbank, Frank William (1984). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Hellenistic World (Volume 7, Part 1). Cambridge University Press.

- Berranger, Cabanes & Berranger-Auserve 2007, p. 133

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 288