Trout Creek Mountains

The Trout Creek Mountains are a remote, semi-arid Great Basin mountain range mostly in southeastern Oregon and partially in northern Nevada in the United States. The range's highest point is Orevada View Benchmark, 8,506 feet (2,593 m) above sea level, in Nevada. Disaster Peak, elevation 7,781 feet (2,372 m), is another prominent summit in the Nevada portion of the mountains.

| Trout Creek Mountains | |

|---|---|

Disaster Peak and spring wildflowers in 2013 | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Orevada View Benchmark |

| Elevation | 8,506 ft (2,593 m) |

| Coordinates | 41°58′46″N 118°13′23″W[1] |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 51 mi (82 km) north–south |

| Width | 36 mi (58 km) west–east |

| Area | 811 sq mi (2,100 km2)including surrounding non-mountainous areas |

| Geography | |

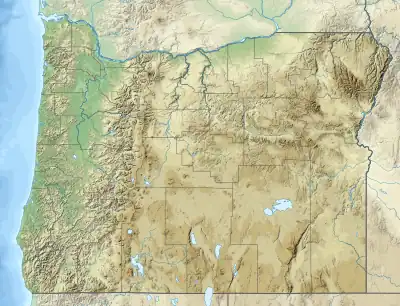

Location of the Trout Creek Mountains in Oregon | |

| Country | United States |

| States | Oregon and Nevada |

| Counties | Harney County, Oregon Humboldt County, Nevada[2][n 1] |

| Range coordinates | 42°06′0″N 118°17′34″W[2] |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Triassic, Cretaceous and Miocene epoch |

| Type of rock | Volcanic; uplifted and faulted |

The mountains are characteristic of the Great Basin's topography of mostly parallel mountain ranges alternating with flat valleys. Oriented generally north to south, the Trout Creek Mountains consist primarily of fault blocks of basalt, which came from an ancient volcano and other vents, on top of older metamorphic rocks. The southern end of the range, however, features many granitic outcrops. As a whole, the faulted terrain is dominated by rolling hills and ridges cut by escarpments and canyons.

Most of the range is public land administered by the federal Bureau of Land Management. There is very little human development in the remote region—cattle grazing and ranching are the primary human uses—but former mines at the McDermitt Caldera produced some of the largest amounts of mercury in North America in the 20th century. Public lands in the mountains are open to recreation but are rarely visited. Vegetation includes large swaths of big sagebrush in addition to desert grasses and cottonwood and alder stands. Sage grouse and mountain chickadee are two bird species native to the range, and common mammals include pronghorn and jackrabbits.

Despite the area's dry climate, a few year-round streams provide habitat for the rare Lahontan cutthroat trout. Fish populations in the Trout Creek Mountains declined throughout much of the 20th century. In the 1980s, the effects of grazing allotments on riparian zones and the fish led to land-use conflict. The Trout Creek Mountain Working Group was formed in 1988 to help resolve disagreements among livestock owners, environmentalists, government agencies, and other interested parties. The stakeholders met and agreed on changes to land-use practices, and since the early 1990s, riparian zones have begun to recover.

Geography

The Trout Creek Mountains are in a very remote area of southeastern Oregon and northern Nevada,[5] in Harney and Humboldt counties.[2][n 1] The nearest human settlements are the Whitehorse Ranch, about 20 miles (32 km) directly north from the middle of the mountains; Fields, Oregon, about 23 miles (37 km) to the northwest; Denio, Nevada, about 15 miles (24 km) to the west; and McDermitt, Nevada–Oregon, about 30 miles (48 km) to the east.[7][8] The mountains are about 150 miles (240 km) directly southwest of Boise, Idaho, and about 190 miles (310 km) northeast of Reno, Nevada.[7]

The range and surrounding non-mountainous areas cover an area of 811 square miles (2,100 km2). The mountains run 51 miles (82 km) north to south and 36 miles (58 km) east to west. More of the range is in Oregon (78%) than in Nevada (22%). The highest point in the range is Orevada View Benchmark, which is 8,506 feet (2,593 m) above sea level and is located in Nevada about one mile south of the Oregon border.[1][5] About two miles southeast of Orevada View is Disaster Peak,[9] "a large, symmetrical butte that is visible throughout the region."[10] At 7,781 feet (2,372 m), Disaster Peak anchors the southern end of the mountains in a sub-range called The Granites.[5][11]

The Oregon Canyon Mountains border the Trout Creek Mountains on the east along the Harney–Malheur county line (according to the United States Geological Survey's definitions),[2][6][12][n 1] while the Pueblo Mountains are the next range west of the Trout Creek Mountains. The Bilk Creek Mountains in both Oregon and Nevada border the Trout Creek Mountains on the southwest; the two ranges are separated by Log Cabin Creek and South Fork Cottonwood Creek.[13] South of the Trout Creek Mountains is the Kings River Valley, which separates the Bilk Creek Mountains on the west from the Montana Mountains on the east.[14][15]

The terrain in the Trout Creek Mountains varies from broad, flat basins and rolling ridges to high rock escarpments cut by deep canyons. The canyons have steep walls with loose talus slopes at the bottoms. There are meadows around springs in the mountains, although most streams in the range do not flow year-round.[10][16] Major streams that flow off the north slopes of the mountains include (from west to east) Cottonwood Creek, Trout Creek, Willow Creek, and Whitehorse Creek. These streams all flow into endorheic basins in Harney County, Oregon. Trout Creek and Whitehorse Creek are the largest of the four.[3][4][n 2] The Kings River and McDermitt Creek each drain an area on the south slopes of the Trout Creek Mountains.[4] The Kings River begins in The Granites and flows south into Nevada, where it meets the Quinn River, which evaporates in the Black Rock Desert.[4][17] McDermitt Creek begins in Oregon a few miles north of The Granites and flows generally east, crossing the Oregon–Nevada border five times before disappearing into the floor of the Quinn River Valley south of McDermitt.[4][18]

Geology

The mountains lie within the Basin and Range Province of the Western United States, which is characterized by parallel fault blocks that form long north–south mountain ranges separated by wide, high-desert valleys. The Trout Creek Mountains are uplifted and tilted fault blocks with steep escarpments along the southern and eastern sides.[10] The southern area of the range, known as The Granites,[11] has numerous outcrops of Cretaceous granite beneath younger volcanic rocks.[10]

The rocks themselves of the Trout Creek Mountains are primarily basalt from a shield volcano that once stood where Steens Mountain is today.[19] About 17 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch, the Yellowstone hotspot was located beneath the thinning crust of southeastern Oregon and caused eruptions from Steens and nearby vents.[20] The Steens eruptions lasted for about one million years and produced at least 70 separate basaltic lava flows.[19] Subsequent faulting associated with the regional crustal thinning of the Basin and Range uplifted and tilted these rocks to shape them into the Trout Creek Mountains.[10][19]

Beneath the mountains, underlying the basaltic rocks, are much older metamorphic rocks that may be related to some of the Triassic formations of the Blue Mountains in northeastern Oregon. Within these metamorphic rocks are diorite and granodiorite – intrusive bodies that presumably formed during the Cretaceous Period.[21][22]

One broad geologic feature in the Trout Creek Mountains is McDermitt Caldera. The oval-shaped caldera is a collapsed lava dome that straddles the Oregon–Nevada border on the eastern side of the range south of the Oregon Canyon Mountains.[23][24] It is about 28 miles (45 km) long and 22 miles (35 km) wide.[24] The lava dome was created by volcanic eruptions in the early Miocene. A total of five large ash flows were produced along with a large rhyolite dome structure. The caldera formed when the dome collapsed about 16 million years ago.[23] The caldera contains significant ore deposits, and mercury and uranium have been mined at eight or more sites in and around the caldera.[24] Other sites at the caldera were mined for antimony, cesium, and lithium ores.[25]

Climate

The Trout Creek Mountains are semi-arid because they are in the eastern rain shadow of mountain ranges to the west. When moist air from the Pacific Ocean moves eastward over the Oregon and California coastal ranges and the Cascade Range, most precipitation falls in those mountains before reaching the Trout Creek Mountains. As a result, the average annual precipitation in the Trout Creek Mountains is only 8 to 26 inches (200 to 660 mm) per year,[26] with most areas receiving between 8 and 12 inches (200 and 300 mm) annually.[16] Much of the annual precipitation occurs between the beginning of March and the end of June.[27] Most of the rest falls as snow during the fall and winter months. Snowpack at elevations below 6,000 feet (1,800 m) usually melts by April; however, at the higher elevations, snow can remain until mid-June. Local flooding often occurs in the spring as the snowpack melts.[26]

The prevailing winds are from the west-southwest, and they are normally strongest in March and April. Brief, intense thunderstorms are common between April and October. Thunderstorms in the summer months tend to be more isolated and often produce dry lightning strikes.[26]

| Climate data for the Whitehorse Ranch, Oregon (along lower Whitehorse Creek, north of the Trout Creek Mountains) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) |

46.8 (8.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

61.0 (16.1) |

68.8 (20.4) |

77.4 (25.2) |

87.6 (30.9) |

86.5 (30.3) |

77.8 (25.4) |

65.7 (18.7) |

51.0 (10.6) |

40.8 (4.9) |

63.3 (17.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

41.4 (5.2) |

47.1 (8.4) |

54.4 (12.4) |

61.7 (16.5) |

71.0 (21.7) |

69.5 (20.8) |

60.8 (16.0) |

50.5 (10.3) |

38.7 (3.7) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

49.3 (9.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 20.9 (−6.2) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

33.2 (0.7) |

40.0 (4.4) |

46.0 (7.8) |

54.3 (12.4) |

52.5 (11.4) |

43.8 (6.6) |

35.3 (1.8) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

35.4 (1.9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.63 (16) |

0.70 (18) |

0.87 (22) |

0.92 (23) |

0.93 (24) |

0.55 (14) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.68 (17) |

0.54 (14) |

0.57 (14) |

0.67 (17) |

0.71 (18) |

7.98 (202.3) |

| Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Climatic Data Center normals data, 1981–2010[27][28] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Flora

Vegetation in the Trout Creek Mountains is dominated by big sagebrush and desert grasses. Other common shrubs include bitterbrush, snowberry, and Ceanothus. There are also patches of mountain mahogany in some areas. Common grass species include Idaho fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass, cheatgrass, western needlegrass, Sandberg's bluegrass, Thurber's needlegrass, and bottlebrush squirreltail, as well as basin wildrye in some well-drained areas.[29]

Less than one percent of the range consists of meadow wetlands and riparian greenways (vegetation along stream banks). However, these areas are vital to the local ecosystem. The meadows surround springs, which are mostly on gently sloping uplands or in stream bottoms, and range in size from about 1 to 5 acres (0.40 to 2.02 ha). Narrow riparian greenways follow the year-round streams. Many greenway areas have quaking aspen and willow groves. Cottonwood and alder groves can be found at lower elevations where terrain is flatter and stream channels are wider. Sedges and rushes are also native to these stream bottoms. Years of heavy livestock grazing in parts of the range resulted in the loss of some grass species, riparian vegetation, and young aspen and willow trees.[29] Restoration of riparian areas began in the early 1970s,[30] and plans to reduce grazing were implemented in the 1980s and early 1990s.[31] However, large wildfires in southeastern Oregon during the summer of 2012 burned much of the range's vegetation, damaging riparian ecosystems and killing hundreds of grazing cattle.[32][33]

Fauna

.jpg.webp)

Animals in the Trout Creek Mountains are adapted to the environment of the High Desert. Pronghorn are common in the open, sagebrush-covered basins, while mule deer live in the cottonwood and willow groves. There are also bighorn sheep, cougars, and bobcats in the high country. Jackrabbits and coyotes are prevalent throughout the range.[6][34][35][36] Mustangs sometimes pass through the mountains as they roam the Great Basin.[37][38] Some other mammals include the northern pocket gopher, mountain cottontail, and Belding's ground squirrel.[36] North American beavers live in and along streams,[6] as do Pacific tree frogs, western spadefoot toads, and garter snakes.[39] Native bird species include the sage grouse, mountain chickadee, gray-headed junco, black-throated gray warbler, Virginia's warbler, MacGillivray's warbler, pine siskin, red crossbill, bushtit, hermit thrush, northern goshawk,[35] and species of raven and eagle.[40]

Several streams in the Trout Creek Mountains are home to trout, including the rare Lahontan cutthroat trout subspecies. These include Willow Creek, Whitehorse Creek, Little Whitehorse Creek, Doolittle Creek, Fifteen Mile Creek, Indian Creek, Sage Canyon Creek, Line Canyon Creek, and some tributaries of McDermitt Creek.[41] Lahontan cutthroat trout live in small, isolated populations that are often confined to individual streams, many of them in the Trout Creek Mountains. These populations have significant genetic differences due to their history of isolation.[42] For most of the 20th century, the trout's numbers declined considerably. It was listed under federal law as an endangered species in 1970 and was reclassified as threatened in 1975.[41] Reasons for the fish's decline included habitat degradation from cattle grazing, drought, overfishing, competition with other fish, and hybridization with introduced rainbow trout, which decreased the number of genetically pure Lahontan cutthroat trout.[6][39][41][42] However, reductions in cattle grazing in riparian zones since the 1980s allowed fish habitat and populations to start to recover.[16]

Human uses

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administers most land in the Trout Creek Mountains,[10][16][43] but there are also some private lands and some roads in the area.[4] The private lands are mainly used for ranching along mountain streams, while the BLM lands include large grazing allotments for local ranchers' cattle.[4][10][16] At least 100 mining claims in the mountains have been recorded since 1892, some of which were staked for gold exploration.[44] Commercial mining has occurred in some areas, mostly near the McDermitt Caldera, where uranium and large amounts of mercury have been extracted.[10][24][45] Mines in what was called the Opalite Mining District produced 270,000 flasks of mercury—"the richest supply of mercury in the western hemisphere"—from cinnabar extracted from the caldera in the 20th century.[45][n 3] The two leading mercury-producing mines in North America were the Cordero and McDermitt mines on the edge of the caldera in Nevada. Together, they operated from 1933 to 1989.[47] The McDermitt Mine, the last mercury mine in the United States, closed three years later, in 1992.[46] However, mineral exploration has continued at the Cordero Mine in the 21st century,[47] and waste containing mercury and arsenic was returned there from the community of McDermitt as part of a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency cleanup project.[48]

The entire mountain range is very remote; as a result, there are few visitors, and the range offers a wilderness-like experience. Camping, hunting, fishing, and hiking are the most popular activities. The only developed recreation site nearby is at Willow Creek Hot Springs, just south of the Whitehorse Ranch,[49][50] where nearby there are miles of trails designated for four-wheel off-road vehicles.[35] Hunters come to the mountains seeking trophy mule deer, pronghorn, chukars, and rabbits. Fishing on some streams is sometimes permitted on a catch-and-release basis. The mountains are also suitable for hiking cross-country or on game trails in natural corridors along canyons and creek bottoms.[6][10][35][51] There are more than 100 archaeological sites in the range that document use by Northern Paiute people as long as 7,000 years ago.[6][52]

Cattle grazing in the Trout Creek Mountains began in the late 19th century, and the BLM currently oversees grazing allotments in the area. Cattle can be found grazing in some areas during the spring and summer months. The effects of grazing on the local environment were the subject of controversy in the 1980s.[34]

Land-management compromise

By the 1970s and 1980s, a century of intense cattle grazing had reduced much of the riparian vegetation along stream banks in the Trout Creek Mountains and elsewhere in the Great Basin. As a result, stream banks were eroding and upland vegetation was encroaching into riparian zones. Aspen populations declined as grazing cattle eliminated young trees, decreasing shade over streams and raising water temperatures.[34][53][54] These conditions put the rare Lahontan cutthroat trout population at risk. Since the Lahontan was officially designated as a threatened species, environmental groups began advocating the cancellation of grazing permits in the Trout Creek Mountains.[34][53]

Beginning in the early 1970s, the Bureau of Land Management identified damaged riparian zones and began projects to restore natural habitat in those areas. Approximately 20,000 willow trees were planted along streams, small dams were put together to create more pools in the streams, and fencing was added to protect riparian zones from grazing. Next, the agency sought to reform land-use plans to change grazing practices, which became a complex and controversial project.[30]

As environmentalists pressed the BLM to close much of the Trout Creek Mountains to grazing, frustrated ranchers joined the Sagebrush Rebellion seeking to protect their grazing allotments. Initially, it appeared that the issue of grazing in the range would produce prolonged litigation with appeals potentially lasting decades. However, in 1988, interest groups representing all sides of the issue joined to form the Trout Creek Mountain Working Group. The group's goal was to find a solution acceptable to everyone—a plan that would protect both the land's ecological health and ranchers' economic needs.[31][34]

Initial members of the Trout Creek Mountain Working Group included:[31]

- Oregon Cattlemen's Association

- Whitehorse Ranch (the largest ranch in the area)

- Disaster Peak Ranch

- McCormick Ranch

- Zimmerman Ranch

- Wilkinson Ranches

- Oregon Environmental Council

- Oregon Trout

- Izaak Walton League

- Oregon State University

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service

- Bureau of Land Management

Over the next several years, the group continued to meet and discuss options for restoring the land while meeting the economic needs of local ranchers. Meetings were all open to the public.[31]

The group eventually endorsed a grazing management plan that provided for both the ecological health of sensitive riparian areas and the economic well-being of ranchers. In 1989, the Whitehorse Ranch agreed to rest two grazing allotments totaling 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) to restore critical stream greenways and mountain pastures. The ranch's allotment on Fifteen Mile Creek was rested for three years, and its Willow Creek pasture received a five-year rest before grazing was resumed. In addition, the grazing season in mountain pastures was reduced from four months to two, and the total number of cattle released in the allotment areas was reduced from 3,800 to 2,200. Finally, sensitive areas were fenced to protect them from cattle, and additional water sources were constructed away from streams. Other ranches also agreed to rest specific pastures including the Trout Creek, Cottonwood Creek, and Whitehorse Butte allotments.[16][31][55]

In 1991, the Bureau of Land Management approved a new grazing allotment management plan. It was based on the agreements made by the Trout Creek Mountain Working Group, and it took effect in 1992. Since then, vegetation in riparian areas of the Trout Creek Mountains has recovered, and studies by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service have found that the Lahontan cutthroat trout population, still listed as threatened, is also recovering.[16][31][41]

|

|

|

| Cottonwood Creek riparian area before restoration, 1988 | Cottonwood Creek riparian area during recovery, 2000 | Cottonwood Creek riparian area after restoration, 2002 |

See also

Notes

- Some maps and sources consider the Oregon Canyon Mountains to be a sub-range of the Trout Creek Mountains, therefore expanding the breadth of the Trout Creek Mountains into Malheur County, Oregon,[3][4] while some sources consider the two ranges to be separate, with varying definitions of the border between them.[2][5][6]

- Whitehorse Creek flows mostly in Malheur County. Whether or not parts of the stream are in the Trout Creek Mountains depends on how the extent of the range is defined. See note above.

- A flask equals 76 pounds or 34.5 kilograms or 0.035 ton.[46]

References

- "Orevada View Benchmark, Nevada". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Trout Creek Mountains". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 28 November 1980. Retrieved 20 July 2014. This source gives the coordinates for the range's south end, which is in Humboldt County, Nevada.

- Oregon (Map) (1993 ed.). 1:500,000. Cartography by Allan Cartography. Medford, Oregon: Raven Maps & Images. 1987. OCLC 41588689.

- Oregon Road & Recreation Atlas (Map) (Third ed.). Medford, Oregon: Benchmark Maps. 2006. pp. 26, 103–104. ISBN 0-929591-88-7.

- "Trout Creek Mountains". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Kerr, Andy (2000). Oregon Desert Guide: 70 Hikes. Seattle, Washington: The Mountaineers Books. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-89886-602-5. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- The National Map (Map). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 August 2015. The distances given are each measured in a straight line connecting two points.

- Wheat, Dan (8 June 2012). "'Rawhide Country' Thrives on Cattle, History". Capital Press. Salem, Oregon. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Disaster Peak, Nevada". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Disaster Peak Wilderness Study Area" (PDF). Nevada Wilderness Study Area Notebook. Bureau of Land Management. April 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015.

- "The Granites". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 12 December 1980. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Oregon Canyon Mountains". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1 April 1993. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Bilk Creek Mountains". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 12 December 1980. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Kings River Valley". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 12 December 1980. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- "Montana Mountains". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 12 December 1980. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- Elmore, Wayne (15 March 2000). "Trout Creek Mountains, Oregon". The Aurora Project. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019.

- "Quinn River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 12 December 1980. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "McDermitt Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 12 December 1980. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Bishop, Ellen Morris (2003). "Steens Basalt". In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-88192-590-6.

- Orr, Elizabeth L.; Orr, William N. (1999). Geology of Oregon (5th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. pp. 80–86. ISBN 978-0-7872-6608-0. OCLC 42944922.

- McKee, Bates (1972). Cascadia: The Geologic Evolution of the Pacific Northwest. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 978-0-07-045133-9.

- "Pueblo Mountain Wilderness Study Area" (PDF). Nevada Wilderness Study Area Notebook. Bureau of Land Management. April 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2015.

- Rytuba, James J.; Conrad, Walter K. (1981). Goodell, P. C.; Waters, A. C. (eds.). "Petrochemical Characteristics of Volcanic Rocks Associated with Uranium Deposits in the McDermitt Caldera Complex". Studies in Geology. 178: 63–72. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- Rytuba, James J. (1976). "Geology and Ore Deposits of the McDermitt Caldera, Nevada–Oregon" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Rytuba, James J.; McKee, Edwin H. (30 September 1984). "Peralkaline Ash Flow Tuffs and Calderas of the McDermitt Volcanic Field, Southeast Oregon and North Central Nevada". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 89 (B10): 8616–8628. Bibcode:1984JGR....89.8616R. doi:10.1029/JB089iB10p08616.

- "Chapter 2 – Description of the Existing Environment" (PDF). Trout Creek Geographic Management Area – Standards of Rangeland Health Evaluation. Bureau of Land Management. August 2006. p. 13. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "Data Tools: 1981-2010 Normals". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- "Whitehorse Ranch, Oregon, USA: Climate, Global Warming, and Daylight Charts and Data". Climate-Charts.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Description of the Existing Environment", pp. 14–15

- "Whitehorse Butte Allotment - Controversy to Compromise". Vale District Planning Update for the Jordan Resource Area. Bureau of Land Management. September 1991. p. 3. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "About the Trout Creek Mountain Working Group". The Aurora Project. Bureau of Land Management. 15 April 2000. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020.

- "Carefully Restored Habitat of Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Destroyed in Oregon's Holloway Fire; Fishing Suspended". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. 5 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Templeton, Amelia (17 July 2012). "Ranchers Struggle in the Aftermath of Fires". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020.

- Hatfield, Doc; Hatfield, Connie (June 1991). "The Trout Creek Mountain Working Group". Rangelands. Society for Range Management. 13 (3): 112–115. ISSN 0190-0528. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "About the Ranch". Whitehorse Ranch. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012.

- "Mahogany Ridge Wilderness Study Area (OR-2-77)". Oregon Wilderness Environmental Impact Statement. Bureau of Land Management. April 1985. pp. 166, 168. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Southern Malheur Grazing Management Program: Environmental Impact Statement. Bureau of Land Management. 1983. pp. 25–26. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- Richard, Terry (3 July 2009). "Getting Lost in Oregon's Trout Creek Mountains". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015.

- "Description of the Existing Environment", p. 37

- "Oregon Canyon and Trout Creek Mountains". Audubon Society of Portland. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Lahontan Cutthroat Trout". United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Oregon Fish & Wildlife Office. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Lahontan Cutthroat Trout". Chapter 4: Cutthroat Trout. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009.

- "Mahogany Ridge Wilderness Study Area", p. 161

- Minor, Scott A.; Turner, Robert L.; Plouff, Donald; Leszcykowski, Andrew M. (1988). "Mineral Resources of the Disaster Peak Wilderness Study Area, Harney and Malheur Counties, Oregon, and Humboldt County, Nevada" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1742-A. United States Geological Survey. p. A6. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Orr, p. 93

- "Mercury" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2015.

- "Cordero, Nevada". Silver Predator Corp. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Holzel, Dee (1 January 2014). "EPA's $1.2 Million Cleanup in McDermitt Completed: 10,000 Tons of Calcine Taken Home to Cordero". Elko Daily Free Press. Elko, Nevada. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Trout Creek and Oregon Canyon Mountains". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- Richard, Terry (17 September 2012). "Willow Creek Hot Springs Washes off the Dust from an Oregon Desert Odyssey". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- Shewey, John (2014). Complete Angler's Guide to Oregon (Second ed.). Belgrade, Montana: Wilderness Adventures Press. pp. 375, 379. ISBN 978-1-932098-86-0.

- Quinlan, Angus R., ed. (2007). Great Basin Rock Art: Archaeological Perspectives. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-87417-696-4.

- Hanson, Mary. "The Trout Creek Mountain Working Group: A Fifteen-Year Perspective". Archived from the original (Section I, 11) on 22 February 2012. This report is from the Aspen Delineation Project, specifically "Ecology and Management of Aspen Rangelands: The Society of Range Management Annual Meeting" from 11 to 16 February 2007 in Reno, Nevada.

- Belsky, A.J.; Matzke, A.; Uselman, S. (1999). "Survey of Livestock Influences on Stream and Riparian Ecosystems in the Western United States" (PDF). Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 54: 419–431. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Trout Creek Mountains Restoration" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2015.

External links

- The Aurora Project – Trout Creek Mountains Community Watershed Partnership

- Report on Archaeology in the Trout Creek-Oregon Canyon Uplands – Bureau of Land Management

- Trout Creek Mountain Area Grazing Management Project – Montana State University

- Study of Beavers and Trout on Willow Creek – Oregon State University