Roosevelt Island

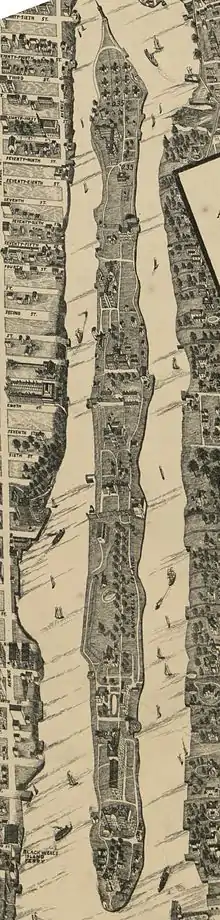

Roosevelt Island is an island in New York City's East River, within the borough of Manhattan. It lies between Manhattan Island to the west, and the borough of Queens, on Long Island, to the east. Running from the equivalent of East 46th to 85th Streets on Manhattan Island, it is about 2 miles (3.2 km) long, with a maximum width of 800 feet (240 m), and a total area of 147 acres (0.59 km2). Together with Mill Rock, Roosevelt Island constitutes Manhattan's Census Tract 238, which has a land area of 0.279 sq mi (0.72 km2),[2] and had a population of 11,722 as of the 2020 United States Census.[3]

Historically called: Minnehanonck / Varkens Eylandt ("Hog Island") / Blackwell's Island / Welfare Island | |

|---|---|

Seen in July 2017 looking southward | |

Location in New York City | |

| Geography | |

| Location | East River, New York County, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°45′41″N 73°57′03″W |

| Area | 0.23 sq mi (0.60 km2) |

| Length | 2 mi (3 km) |

| Width | 0.15 mi (0.24 km) |

| Highest elevation | 23 ft (7 m) |

| Administration | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 11,722 (2020) |

| Pop. density | 50,700/sq mi (19580/km2) |

| Ethnic groups | 45% white, 27% black, 14% Hispanic, 11% Asian or Pacific Islander, and .3% other races (as of 2000)[1] |

Lying below the Queensboro Bridge, the island cannot be accessed directly from the bridge itself. Vehicular traffic uses the Roosevelt Island Bridge to access the island from Astoria, Queens, though the island is not designed for vehicular traffic and has several areas designed as car-free zones. Several public transportation options to reach the island exist. The Roosevelt Island Tramway, the oldest urban commuter tramway in the U.S, connects the island to Manhattan Island's Upper East Side. The Roosevelt Island station carries the F and <F> trains of the New York City Subway. The NYC Ferry also maintains a dock on the east side of the island. On-island transport is provided by the Red Bus service.

The island was called Minnehanonck by the Lenape and Varkens Eylandt (Hog Island) by the Dutch during the colonial era and later Blackwell's Island. It was known as Welfare Island when it was used principally for hospitals, from 1921 to 1973.[4] It was renamed Roosevelt Island (in honor of Franklin D. Roosevelt) in 1973.[5]

Roosevelt Island is owned by the city but was leased to the New York State Urban Development Corporation for 99 years in 1969. Most of the residential buildings on Roosevelt Island are rental buildings. There is also a cooperative named Rivercross and a condominium building named Riverwalk. One rental building (Eastwood) has left New York State's Mitchell-Lama Housing Program, though current residents are still protected. It is now called Roosevelt Landings. There are attempts to privatize three other buildings, including the cooperative. The New York City Fire Department also maintains its Special Operations Command facility at 750 Main St. on the island.[6]

History

17th and 18th centuries

In 1637, Dutch Governor Wouter van Twiller purchased the island, then known as Hog Island, from the Canarsie Indians.[7][8] After the Dutch surrendered to the British in 1664, Captain John Manning acquired the island in 1666, which became known as Manning's Island, and twenty years later, Manning's son-in-law, Robert Blackwell, became the island's new owner and namesake.[9] In 1796, Blackwell's great-grandson Jacob Blackwell constructed the Blackwell House, which is the island's oldest landmark, New York County's sixth oldest house, and one of the city's few remaining examples of 18th-century architecture.[9]

19th century

Through the 19th century, the island housed several hospitals and a prison. In 1828, the City of New York purchased the island for $32,000 (equivalent to $852,752 in 2022), and four years later, the city erected a penitentiary on the island; the Penitentiary Hospital was built to serve the needs of the prison inmates. By 1839, the New York City Lunatic Asylum opened, including the Octagon Tower, which still stands but as a residential building; it was renovated and reopened in April 2006.[10] The asylum, which was designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, at one point held 1,700 inmates, twice its designed capacity.[9]

.tiff.jpg.webp)

In 1852, a workhouse was built on the island to hold petty violators in 220 cells. The Smallpox Hospital, designed by James Renwick, Jr., opened in 1856, and two years later, the Asylum burned down and was rebuilt on the same site; Penitentiary Hospital was destroyed in the same fire.[9] In 1861, prisoners completed construction of Renwick's City Hospital (renamed Charity Hospital in 1870), which served both prisoners and New York City's poorer population.[9] In 1877, the hospital opened a School of Nursing, the fourth such training institution in the nation.[11]

During the impeachment process of New York State Supreme Court Justice George G. Barnard in 1872, the first charge that the New York City Bar Association brought against Barnard was that he discharged at least 39 prisoners from the Blackwell's Island penitentiary before their sentence was expired.[12]

In 1872, the Blackwell Island Light, a 50-foot (15 m) Gothic style lighthouse later added to the National Register of Historic Places, was built by convict labor on the island's northern tip under Renwick's supervision. Seventeen years later, in 1889, the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, designed by Frederick Clarke Withers, opened.[9] By 1895, inmates from the Asylum were being transferred to Ward's Island, and patients from the hospital there were transferred to Blackwell's Island. The Asylum was renamed Metropolitan Hospital. However, the last convicts were not moved off the island until 1935, when the penitentiary on Rikers Island opened.[9]

20th century

The 20th century was a time of change for the island. The Queensboro Bridge started construction in 1900 and opened in 1909; it passed over the island but did not provide direct vehicular access to it at the time.[9] In 1921, Blackwell's Island was renamed Welfare Island[4] after the City Hospital on the island.[13] In 1930, a vehicular elevator to transport cars and passengers on Queensboro Bridge started to allow vehicular and trolley access to the island.[14][15]

In 1939, Goldwater Memorial Hospital, a chronic care facility, opened, with almost a thousand beds in 7 buildings on 9.9 acres (4.0 ha). Thirteen years later, Bird S. Coler Hospital, another chronic care facility, opened, and three years after the Coler Hospital's opening, Metropolitan Hospital moved to Manhattan, leaving the Lunatic Asylum buildings abandoned.[9] The same year, 1955, the Welfare Island Bridge from Queens opened, allowing automobile and truck access to the island and the only non-aquatic means in and out of the island; the vehicular elevator to Queensboro Bridge then closed,[14] but was not demolished until 1970.[15] As late as August 1973, another passenger elevator ran from the Queens end of the bridge to the island.[16][17]

More changes came in the latter half of the century. In 1968, the Delacorte Fountain, opposite the headquarters of the United Nations, opened.[9] Mayor John V. Lindsay named a committee to make recommendations for the island's development in the same year.[18] A year later, the New York State Urban Development Corporation (UDC) signed a 99-year lease for the island, and architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee created a plan for apartment buildings housing 20,000 residents. In 1973,[5] Welfare Island was renamed Roosevelt Island in honor of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and two years later, planning for his eponymous park, Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, started.[4]

Federal funding for redevelopment came from the New Community Act. In 1976, the Roosevelt Island Tramway opened, connecting the island directly with Manhattan,[19] but it was eight years before the New York State legislature created the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation (RIOC) to operate the tramway, with a nine-person board of directors appointed by the Governor, two suggested by the Mayor of New York City, and three of whom are residents of the island.[9] The tramway was meant as a temporary solution to the then-lack of subway service to the island, which began in 1989 with the opening of the Roosevelt Island station[20] (serving the F train).[21]

21st century

During the 21st century, the area became more gentrified. In 1998, the Blackwell Island Light was restored by an anonymous donor.[9] In 2006, the restored Octagon Tower opened, serving as the central lobby of a two-wing, 500-unit apartment building.[9] In 2010, the Roosevelt Island Tramway reopened after renovations.[22] A year later, Southpoint Park opened south of Goldwater Memorial Hospital, near the island's southern end,[23] Cornell Tech, a joint venture between Technion – Israel Institute of Technology and Cornell University, was announced the same year.[24][25]

In 2012, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park was dedicated and opened to the public as a state park.[26] Hillary Clinton officially launched her 2016 presidential campaign at Four Freedoms Park in 2015.[27] Construction of the new Cornell Tech campus began in January 2014 with the arrival of equipment on Roosevelt Island for the building of a fence around the construction site and for the demolition of the existing Coler-Goldwater Specialty Hospital's south campus; demolition began in March 2014,[28] but city officials say they do not have plans to close the north campus of the hospital.[29] The school began operations on the island in fall 2017.[30]

On June 24, 2019, the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation (RIOC) published an open call for artists to create a memorial for journalist Nellie Bly.[31] Bly's investigative reporting about the abusive treatment at the New York City Insane Asylum at what was then called Blackwell's Island, led to new forms of journalism as well as the reform of New York City institutions. In October, a committee of RIOC employees and community leaders selected The Girl Puzzle proposal by American artist Amanda Matthews.[32] The public art installation of a plaza featuring bronze sculptures, stainless steel spheres and a fully accessible walkway was planned for unveiling in 2021.[33]

Architecture

Though small, Roosevelt Island has a distinguished architectural history. It has several architecturally significant buildings and has been the site of numerous important unbuilt architectural competitions and proposals. The island's master plan, adopted by the New York State Urban Development Corporation in 1969, was developed by the firm of Philip Johnson and John Burgee. The plan divided the island into three residential communities, and it forbade the use of automobiles on the island; the plan intended for residents to park their cars in a large garage and use public transportation to get around. Another innovation was the plan's development of a 'mini-school system,' in which classrooms for the island's public intermediate school were distributed among all the residential buildings in a campus-like fashion (as opposed to being centralized in one large building).

The first phase of Roosevelt Island's development was called "Northtown". It consists of four housing complexes: Westview, Island House, Rivercross, and Eastwood (also known as the WIRE buildings). Rivercross is a Mitchell-Lama co-op, while the rest of the buildings in Northtown are rentals. Eastwood, the largest apartment complex on the island, and Westview were designed by noted architect Josep Lluis Sert, then dean of Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Eastwood, along with Peabody Terrace (in Cambridge, Massachusetts), is a prime example of Sert's high-rise multiple-dwelling residential buildings. It achieves efficiency by triple-loading corridors with duplex apartment units, such that elevators and public corridors are only needed every three floors. Island House and Rivercross were designed by Johansen & Bhavnani. The two developments were noteworthy for their use of pre-fabricated cladding systems.

Subsequent phases of the island's development have been less innovative, architecturally. Northtown Phase II was developed by the Starrett Corporation and designed by the firm, Gruzen Samton, in a pseudo-historical post-modern style. It was completed in 1989, over a decade after Northtown. Southtown (also referred to as Riverwalk by the developers[34]) is the third phase of the island's development. This phase, also designed by Gruzen Samton, was not started until 1998 and is still in the process of development. When complete, Southtown will have 2,000 units in nine buildings.[35]

The Octagon, one of the island's six landmarks, was restored in April 2006, and the national landmark building is now part of a high-end apartment complex. It also houses the largest array of solar panels on any building in New York City. When The Octagon opened its doors, many young, affluent tenants started to occupy the studios and one-, two-, and three-bedroom units; 100 of the units therein are set aside for middle-income residents.

In 2006, ENYA (Emerging New York Architects) made the island's abandoned southern end the subject of one of its annual competitions. In addition to Louis Kahn's 4-acre (1.6 ha) Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at that tip, whose public dedication on October 17, 2012 was tangled in litigation,[36][37] the island has also been the site of numerous other architectural speculations. Rem Koolhaas and the Office of Metropolitan Architecture proposed two projects for the Island in his book "Delirious New York": the Welfare Island Hotel and the Roosevelt Island Redevelopment Proposal (both in 1975–76). That proposal was Koolhaas's entry into a competition held for the development of Northtown Phase II. Other entrants included Peter Eisenman, Robert A. M. Stern, and Oswald Mathias Ungers.

As of 2013, six of the Southtown buildings, with a total of 1,200 units, have been completed. Residential development of Southtown has brought new retail businesses to Roosevelt Island.

Transportation

_01.jpg.webp)

Although Roosevelt Island is located directly under the Queensboro Bridge, it is no longer directly accessible from the bridge itself. A trolley previously connected passengers from Queens and Manhattan to a stop in the middle of the bridge, where passengers took an elevator down to the island. The trolley operated from the bridge's opening in 1909 until April 7, 1957.[14] Between 1930 and 1955, the only vehicular access to the island was provided by an elevator system in the Elevator Storehouse that transported cars and commuters between the bridge and the island. The elevator was closed to the public after the construction of the Roosevelt Island Bridge between the island and Astoria in Queens in 1955; the elevator was demolished in 1970, but a similar elevator ran from the Queensboro Bridge to the island as late as 1973.

In 1976, the Roosevelt Island Tramway was constructed to provide access to Midtown Manhattan. The tram was closed from March to November 2010, during which time all of the components of the tramway, except for the tower bases, were replaced.[38][39]

New York City Subway access to the rest of Manhattan and to Long Island City in Queens via the IND 63rd Street Line began in 1989, but access to the rest of Queens did not start until 2001.[note 1] Located more than 100 feet (30 m) below ground level, the Roosevelt Island station (F train) is one of the deepest stations below sea level in the system. The BMT 60th Street Tunnel (N, R, and W trains) and the IND 53rd Street Line (E, F, and <F> trains) both pass under Roosevelt Island, without stopping, on their way between Manhattan and Queens.[40]

Roosevelt Island's residential community was not designed to support automobile traffic during its planning in the early 1970s. Automobile traffic has become common even though the northern and southern tips of the island remain car-free areas. Visitors can access the island by car over the Roosevelt Island Bridge but must park in the Motorgate Garage for overnight stays or in metered roadside spaces for short-term visits. MTA Bus's Q102 route, operating between the island and Queens, obviates the need for automobiles to some extent. However, RIOC operates the Red Bus, a free on-island shuttle bus service. The service uses easily visible bright red buses, and competes directly with the Q102 in connecting apartment buildings to the subway and tramway.

Roosevelt Island has been served by NYC Ferry's Astoria route since August 2017.[41][42][43] The ferry landing is on the east side of the island near the tramway station.

Demographics

2000 US Census

As of the 2000 US Census, Roosevelt Island had a population of 9,520. Fifty-two percent of the population (4,995) were female, and 4,525, or 48%, were male. The population was spread out, with 5% under the age of 5, 20% under the age of 18, 67% between the ages of 18 and 65, and 15% over the age of 65.[1]

The racial makeup of the island was 45% white (non-Hispanic), 27% black (non-Hispanic), 14% Hispanics or Latinos of any race, 11% Asian or Pacific Islander, and .3% other races.[1]

The median income was $49,976. 37% had an income under $35,000. 40% had incomes between $35,001 and $99,999, and 23% had an income over $100,000.[1]

55% of the total households were family households, and 45% were non-family households. 17% of the residents were married couples with children, and 19% were married couples without children. 36% of the households were one-person households, and 9% were two or more non-family households. 3% were male-based households with related and unrelated children, and 16% were female-based households with related and unrelated children.[1]

2010 US Census

As of the 2010 US Census, Roosevelt Island had a population of 11,661. The racial makeup of the island was 54.4% white, 23.4% black, 14.9% Hispanics or Latinos of any race, 20.0% Asian, 0.6% Native American or Pacific Islander, and 5.4% other races.[44] 42.7% of the population was born outside the US.[44]

The median income was $76,250. 69.3% of households earned more than $50,000. 30.5% earned less than $50,000.[44]

2020 US Census

As of the 2020 US Census, Roosevelt Island had a population of 11,722.[3]

International population

Due to its proximity to the headquarters of the United Nations, Roosevelt Island is home to a large number of diplomatic sector employees. At one time these included then-United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan.[45]

In addition to several Christian denominations, the island is home to two Jewish synagogues, and as of 2019, a mosque via the Islamic Society of Roosevelt Island.[46] In September 2017, Chabad of Roosevelt Island, the island's Chabad-Lubavitch Jewish congregation, launched a Chabad Jewish student organization in concert with the launch of Israeli-affiliated Cornell Tech, seeking to provide for the spiritual needs of international students from Israel.[47]

Between the 2000 and 2010 Censuses, Roosevelt Island saw a 9% growth in the percentage of residents who identified as Asian. A large proportion of this growth has been driven by Chinese international student enrollments which skyrocketed following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, seeing local schools such as Columbia University receiving the fifth-largest enrollment of Chinese students in the United States during the 2014–2015 school year.[48][49] The Chinese student and young professional population on the island has led to an increase in the number of businesses accepting payments via Mainland China mobile applications, as well as restaurants featuring regional Chinese cuisine and Chinese-language religious outreach.[50][51][52]

Government and infrastructure

The neighborhood is part of Manhattan Community District 8. The Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation operates and maintains the island's government and infrastructure. The United States Postal Service operates the Roosevelt Island Station at 694 Main Street.[53]

Garbage on Roosevelt Island is collected by an automated vacuum collection (AVAC) system using a system of pneumatic tubes that measure either 20 inches (510 mm),[54] 22 inches (56 cm),[55] or 24 inches (61 cm) wide.[56] Manufactured by Swedish firm Envac and installed in 1975, it was the second AVAC system in the U.S. at the time of its installation, after the Disney utilidor system.[54][56] It is one of the world's largest AVAC systems,[55] collecting trash from 16 residential towers.[54] Trash from each tower is transported to the Central Collections and Compaction Plant,[55] traveling through the tubes at up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h).[54] The collection facility contains three turbines that spin the garbage;[56] the trash is then compacted and sent to a landfill.[54][56] The pneumatic tube system collects 6 short tons (5.4 t)[56] or 10 short tons (9.1 t) of trash each day.[55] On several occasions, tenants have damaged the system by throwing large objects, such as strollers and Christmas trees, into the tubes.[54][56]

Since 2003, Roosevelt Island has not had its own fire station.[57] Engine Company 261, in Long Island City, was near the Roosevelt Island Bridge and served the island until mayor Michael Bloomberg closed it, and five other stations, on May 26, 2003.[58] There was controversy over the firehouse's closure, as Community Board 8 had not been sufficiently notified in advance;[59] a New York Supreme Court judge subsequently ruled that the closure was illegal.[60] In 2019, mayor Bill de Blasio's office told reporters that the island had "additional resources in place in the event they are needed for an emergency."[57]

Recreation

There are four recreational fields on Roosevelt Island:[61]

- Capobianco Field, located south of the Roosevelt Island Bridge ramp; measures 175 by 230 feet (53 by 70 m)

- Firefighters Field, located next to the ferry terminal north of Queensboro Bridge; measures 303 by 178 feet (92 by 54 m)

- McManus Field, located across from the New York City Department of Sanitation building at the north end of the island. As of 2019 it is currently closed for renovations.[62] The park was renamed from Octagon Field in October 2019 to honor Jack McManus, the former Chief of the Roosevelt Island Public Safety Department.[63]

- Pony Field, located east of the Octagon; measures 250 by 230 feet (76 by 70 m)

In addition, the four-acre (1.6 ha) Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park is located at the extreme south end of Roosevelt Island.[64] Four Freedoms Park, a New York State Park, opened on October 24, 2012. The park is named after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Four Freedoms speech, which he made to the United States Congress in 1941.[65] Directly to the north is Southpoint Park, a seven-acre (2.8 ha) green space containing the landmark Strecker Lab and Smallpox Hospital buildings.[66]

At the northern tip of Roosevelt Island is another park, Lighthouse Park, named after the Blackwell Island Light.[67]

The entire island is circled by a publicly accessible waterfront promenade.[68]

Education

Roosevelt Island, like all parts of New York City, is served by the New York City Department of Education. Residents are zoned to PS/IS 217 Roosevelt Island School, which opened in 1992, combining schools at various locations on the island.[9] Some of the locations that formerly housed the fragments of PS/IS 217 now house The Child School and Legacy High School, which serve K–12 special needs children with learning and emotional disabilities.

On December 19, 2011, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that Cornell Tech, a Cornell University-Technion-Israel Institute of Technology graduate school of applied sciences, would be built on the island. The $2 billion facility includes 2 million square feet of space on an 11 acre city-owned site, which was previously used for a hospital. Classes began off-site in September 2012 at the Google New York offices, and the first classes on the Roosevelt Island campus began on September 13, 2017. The first phase of the campus includes main academic building, a graduate housing tower, and an innovation hub/tech incubator. Construction of a conference center and a hotel began in 2018.[69][70][24][25]

Library

The New York Public Library operates the Roosevelt Island branch at 504 Main Street. The library began in a community room, then moved to its own building at 524 Main Street in 1979.[71] The library on Main Street was named the Dorothy and Herman Reade Library of Roosevelt Island in honor of a local couple who had founded the island's first, unofficial, library collection.[72] In 1998, the library became a branch of the NYPL system.[71][9] The current location at 504 Main Street opened in January 2021 and covers 5,200 square feet (480 m2).[73][74]

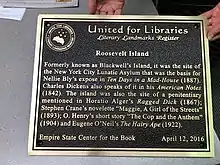

On April 12, 2016, the Empire State Center for the Book dedicated a United for Libraries Literary Landmark plaque marking Roosevelt Island's literary connections.[75]

Organizations

The Roosevelt Island Garden Club has existed since 1975. Each gardener is assigned a plot and can choose to grow what they wish. The club is made up mostly of Island Residents that rent plots to grow all kinds of different plants. The membership is $65 a year and the wait list is extremely long. Visitors can view for free on Saturdays and Sundays.[76]

Media

Roosevelt Island has three dedicated news sources.

- The Roosevelt Island Daily, is a community blog maintained by David Stone since April 2016.[77]

- The Roosevelt Islander, is a community blog maintained by Rick O'Conor.[78]

- The Main Street WIRE, was founded in 1979 by Dr. Jack Resnick and usually published about every two weeks (monthly in July and August).

Notable residents and visitors

.jpg.webp)

Due to its proximity to the United Nations Headquarters, Roosevelt Island has long been a popular neighborhood for diplomats and United Nations staff.[44]

Prisoners

- George Appo - A pickpocket and con artist. A biographer provides a description of the penitentiary on Blackwell's Island in the later half of the 19th century as having lax security, with prisoners being able to escape if they knew how to swim.[79]

- Ida Craddock – convicted for obscenity under the Comstock laws

- Ann O'Delia Diss Debar - served six months for fraud as a medium

- George Washington Dixon – served six months for libel against Reverend Francis L. Hawks

- Fritz Joubert Duquesne – Nazi spy and leader of the Duquesne Spy Ring, the largest convicted espionage case in United States history

- Becky Edelson – for "using threatening language" during a speech[80]

- Carlo de Fornaro – for criminal libel, in 1909

- Emma Goldman – several times, for activities in support of anarchism and birth control and against the World War I draft

- Billie Holiday – served on prostitution charges

- Mary Jones – a 19th-century transgender prostitute who was a center of media attention for coming to court wearing feminine attire.[81]

- Peter H. Matthews – for operating policy games (illegal lotteries) all over New York City

- Patrick McLaughlin – Tammany Hall tough

- Eugene Reising – firearms designer convicted of violating the Sullivan Act[82]

- Madame Restell – for performing abortions

- Dutch Schultz – arrested for burglary

- Boss Tweed – served one year on corruption-related charges

- Mae West – served eight days on public obscenity charges for her play Sex

Visitors

- Charles Dickens – described conditions at the "Octagon", an asylum for the mentally ill then located on the northern portion of the island, in his American Notes (1842)

- William Wallace Sanger – oversaw police interviews of 2000 prostitutes at Blackwell's Island and wrote up the findings in The History of Prostitution (1858)

- Joseph Lister - near the end of his trip to the United States, Lister, at the invitation of surgeon William Van Buren, performed an operation at Charity Hospital on Blackwell's Island. (1876)

- Nellie Bly – went undercover as a patient in the Women's Lunatic Asylum and reported what happened in the New York World as well as her book Ten Days in a Mad-House (1887)

Residents

Current residents

- Jonah Bobo (born 1997) – actor[83]

- Michael Brodsky (born 1948) – author[84]

- Roy Eaton (born 1930) – pianist[85]

Former residents

- Kofi Annan (1938–2018) – United Nations Secretary-General[86]

- Michelle Bachelet (born 1951) – president of Chile and Executive Director of the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women)[87]

- Alice Childress (1912–1994) – playwright and author[88]

- Billy Crawford (born 1982) – singer, songwriter and actor[89]

- Mike Epps (born 1970) – stand-up comedian, actor, film producer, writer and rapper, best known for playing Day-Day Jones in Next Friday and its sequel, Friday After Next[90]

- Wendy Fitzwilliam (born 1972) – former Miss Universe and Miss Trinidad and Tobago[91]

- Amanda Forsythe (born 1976) – light lyric soprano known for her interpretations of baroque music and the works of Rossini[92]

- Buddy Hackett (1924–2003) – comedian and actor[93]

- Tim Keller (1950-2023) – Christian author and minister[94]

- Al Lewis (1923–2006) – actor, best known as "Grandpa" in The Munsters[95][96]

- Sarah Jessica Parker (born 1965) – actress[97]

- Andrea Rosen (born 1974) – comedian[98]

- Jon Sciambi (born 1970) – ESPN broadcaster[99]

- Lyndsey Scott – model, actress, iOS mobile app software developer[100]

- Fez Whatley (1964–2021) – co-host of The Ron and Fez Show on Sirius XM satellite radio

- Paul Feinman (1960–2021) – associate judge of the New York Court of Appeals[101]

In popular culture

Literature

- 1867 – In chapter 13 of Horatio Alger's novel Ragged Dick: Or, Street Life in New York with the Boot Blacks, the character Mickey Maguire, a young tough from Five Points "had acquired an ascendency [sic] among his fellow professionals, and had a gang of subservient followers, whom he led on to acts of ruffianism, not infrequently terminating in a month or two at Blackwell's Island".

- 1893 – In the opening chapter of Stephen Crane's novelette "Maggie: A Girl of the Streets", "a worm of yellow convicts" is seen emerging from a prison building on Roosevelt Island.

- 1904 – In O. Henry's short story "The Cop and the Anthem", the main character, a homeless man named Soapy, schemes to have himself arrested so as to spend the harsh winter serving a three-month sentence in Blackwell's Island prison.

- 1922 – Yank, the main character in Eugene O'Neill's comedy The Hairy Ape, is imprisoned in Blackwell's Island prison, in chapter VI.

- 1925 – Roosevelt Island appears in F. Scott Fitzgerald's classic novel The Great Gatsby as Blackwell's Island, in Chapter Four, when Nick and Jay drive into Manhattan via the Queensboro Bridge.

- 2001 – Roosevelt Island's ruins, particularly the Smallpox Hospital and the Strecker Memorial Laboratory, play a central role in Linda Fairstein's police procedural novel The Dead House (Scribner 2001).

- 2004 – A significant scene in Caitlín R. Kiernan's story "Riding The White Bull" takes place on Roosevelt Island.

- 2005 – In the novel by Caroline B. Cooney, Code Orange, the main character, Mitty, is studying smallpox for his own survival. He goes and visits the Smallpox Hospital ruins on Roosevelt Island.

- 2007 – In the novel by Cassandra Clare, City of Bones, the protagonist is drawn to the island for a showdown with the elusive villain, Valentine.

- 2022 - In the novel by Warren Mead, The Pox Academy, the main character, Lincoln, lives in a secret magic school on the site of the former Smallpox Hospital.

Film

- 1932 – A Paramount Pictures film entitled No Man of Her Own is released, a light comedy film starring Clark Gable and Carole Lombard. Upon learning that Gable's character is not in South America, but instead learns he has negotiated a deal to serve 90 days and "he's across the river", Lombard's character then looks out of her hotel window to a view across the East River and the Queensboro Bridge, later referring to this as "Blackwell's Island".

- 1939 – A Warner Bros. film entitled Blackwell's Island is released. It stars John Garfield as a crusading reporter investigating corruption in the island's prison.[102]

- 1966 – In the film Mister Buddwing, a sign posted on a bridge in the film reads "Stairway to Welfare Island". Suzanne Pleshette, playing the character Grace, tries to throw herself off the bridge wearing nothing but a fitted trench coat and white ankle boots, before James Garner's character saves her.

- 1972 – The Exorcist begins principal photography in mid-August with a scene shot at Goldwater Memorial Hospital.[103]

- 1981 – A Roosevelt Island Tramway car is held hostage in the Sylvester Stallone film Nighthawks.

- 1983 – The 1983 Italian B movie Escape from the Bronx has a scene filmed at the north end of the island.

- 1985 – In the final scenes of the film Turk 182 the Timothy Hutton character swings above Roosevelt Island on the Queensboro Bridge.

- 1990 – In the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film, exterior shots of the Renwick Ruins are used as the fictitious location for the Foot Clan's secret hideout.

- 1991 – In the opening scene of City Slickers Billy Crystal's character "Mitch Robbins" is shown commuting to work via the Roosevelt Island tram.

- 1993 – In the film For Love or Money, Doug Ireland (played by Michael J. Fox) wants to buy the "abandoned hotel" at the south end of Roosevelt Island, referring to the ruins of the Smallpox Hospital.

- 1994 – In The Professional, Mathilda Lando (played by Natalie Portman) takes the Tramway to Roosevelt Island to seek asylum at what is implied to be the Spencer School; however, in the beginning of the film the school's head mistress states on the phone that the school is located in Wildwood, New Jersey.

- 1997 – The film Conspiracy Theory was shot on location in and around New York City, including Roosevelt Island.

- 2001 – The fictional "Saint Adonis Cemetery" in the film Zoolander was built on Roosevelt Island.

- 2002 – Near the end of the film Spider-Man, the Green Goblin blows up the Roosevelt Island side tram station and leaves a group of children hanging inside one car. He also brings Spider-Man down to fight with him in the abandoned Smallpox Hospital on the island. The tram and the island make other appearances in Spider-Man media. The island is featured in the video game Spider-Man 2. In The Amazing Spider-Man #161 and #162, appearing on the cover of the latter,[104] and Spider-Man and Hulk fight on Roosevelt Island in The Amazing Spider-Man #328.

- 2002 – In the film Gangs of New York, Leonardo DiCaprio's character Amsterdam Vallon is seen leaving "Hellgate House of Reform, Blackwell's Island, New York City".

- 2003 – In the film Anything Else, Woody Allen's character, David Dobel, is a schoolteacher who lives on the island.

- 2005 – Roosevelt Island is the setting for the film Dark Water by Brazilian director Walter Salles, where Dahlia (Jennifer Connelly) moves into a low-rent apartment with her daughter and then is terrorized by the ghost of a girl that used to live upstairs.

- 2007 – In the film The Brave One, starring Jodie Foster, a scene takes place at the Roosevelt Island parking lot. The film mentions the island several times.

- 2009 – In the final scene of Daddy Longlegs, the characters board a tram for Roosevelt Island.

- 2023 - In the film John Wick: Chapter 4, there is a scene where Wick (Keanu Reeves) meets with Winston (Ian McShane) at a cemetery. This scene was filmed on Roosevelt Island, with the cemetery on the site of the real world Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park.[105]

Television

- 1958 – In the "Violent Circle" episode of Naked City (season 1, episode 5), Detective Halloran (James Franciscus) poses as a mental patient in a hospital mental ward on the Island to uncover a murderer.

- 1963 – In the "Carrier" episode of Naked City (season 4, episode 29), a woman (Sandy Dennis) escapes from a chronic care hospital on Welfare Island – as it was then called – to carry a rare disease through New York City.

- 1993 – in the "American Dream" episode of Law & Order (season 4, episode 8), a body is found during archaeological excavation on Roosevelt Island, forcing a new trial of a Wall Street broker (Željko Ivanek) who had been convicted based on a witness claiming they had buried the body in New Jersey in the early '80s.[106]

- 2005 – In the second season episode of CSI: NY called "Dancing with the Fishes", a crime is committed inside the Roosevelt Island tram.

- 2010 – On the TV show 24, NY CTU is based on Roosevelt Island.

- 2010 – The reality TV show America's Next Top Model filmed a photo shoot on the Roosevelt Island tram on April 7.

- 2011 – The television series Unforgettable takes place in part on Roosevelt Island.

- 2012 – The season three finale of White Collar is set largely on Roosevelt Island, including a stunt in which the show's protagonist jumps midair between Tram cars to avoid being captured by the FBI.

- 2013 - The second season episode "On The Line" of Elementary opens with a woman shooting herself on the Roosevelt Island Bridge and staging it to look like a murder in order to frame the man who got away with killing her sister.

- 2015 - In season four, episode sixteen of the TruTV show Impractical Jokers, "Captain Fatbelly", a punishment is filmed on the Roosevelt Island Tram. During the scene Joe Gatto performed several strange tasks while riding on top of the tram dressed as the superhero "Captain Fatbelly".

- 2015 – The second season of FX's series The Strain has several scenes which take place on Roosevelt Island.

- 2016 – In the third season episode '"P is For Pancake", of TV Land's series Younger, a potential love interest for Hilary Duff's character is rebuffed when he is revealed to be a resident of Roosevelt Island.[107]

- 2018 – In the Netflix original miniseries Maniac, Jonah Hill's character lives on Roosevelt Island.

- 2019 - The fourth season episode "Maximum Recreational Depth" of Billions, first broadcast on April 21, features a meeting between Wendy Rhoades and Taylor Mason at the FDR Four Freedoms State Park, where they discuss Roosevelt’s State of the Union speech and the relationship between architect-designer Louis Kahn and his son.

- 2019 - The seventh season episode "Into The Woods" of Elementary, first broadcast on June 20, has Joan meet with billionaire Odin Reichenbach at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park; at the end of the episode, she and Sherlock meet him there again to confront him over sending them on a wild goose chase. The following episode, "Command: Delete", immediately follows up on this, continuing this meeting.

Video games

- 1992 – In the final level of the video game Atomic Runner for the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis the level takes place on Roosevelt Island Southpoint Park.

- 2008 – In the video game Grand Theft Auto IV there is an island resembling Roosevelt Island, named Colony Island. It also includes the ruins of a hospital, similar to the Smallpox Hospital. There is also a replica of the tram available for players to ride.

- 2011 – Parts of the video game Crysis 2 take place on Roosevelt Island.

Other

- 1973 – In the original video for Pink Floyd's song "Us and Them", Roosevelt Island appears during a lengthy sequence shot from the Queensboro Bridge.[108]

- 1986 – The King Kong Tramway ride at Universal Studios Hollywood opens, featuring the Roosevelt Island Tram. Another version of the ride would open at Universal Studios Florida in 1990.[109]

- 2006 – The fictional high school which the main characters attend in the GONZO anime series Red Garden is on Roosevelt Island.

- 2009 – On May 23, the island was the site of Improv Everywhere's "MP3 Experiment Six". Approximately 4,500 people traveled to the island to take part in a performance art piece where the southernmost point of the island became a "battleground" for the re-enactment of a fictional melee between townspeople and an ancient wolf.

References

Informational notes

- See History of the 63rd Street Line and the articles for the 63rd Street Shuttle, B, F, and Q trains, for more information.

Citations

- "Community". Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation. Archived from the original on October 31, 2006. Retrieved June 16, 2006.

- "U.S. Census website". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- Pollak, Michael (December 14, 2012). "Name that Island". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- vanden Heuvel, William J. "Memorial Park Honoring Franklin D. Roosevelt". Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "Special Operations Command". www.FDNYtrucks.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Rodriguez-Nava, Gabriel (2003). "The Rise of a Healthy Community". NYC24. Columbia University School of Journalism. Archived from the original on August 1, 2009.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8., p. 29

- "Timeline of Island History". The Main Street Wire. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010.

- Brockmann, Jorg; Harris, Bill (2002). One Thousand New York Buildings. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-57912-237-9.

- "Finding Women in the Archives: Student Nurses". Women at the Center. New-York Historical Society. January 9, 2018. Archived from the original on July 31, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- "Documents of the State of New York Volume 6 - Charges Against Justice George G. Barnard, and Testimony Thereunder, Before the Judiciary Committee of the Assembly". Weed, Parsons and Company, Printers. 1872. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- "Smallpox Hospital (Renwick Ruin)". rihs.us. Roosevelt Island Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 4, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- McCandlish, Phillips (April 7, 1957). "City's Last Trolley at End of Line; Buses Will Replace 49-Year Route on Queensboro Span". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- "Transportation". Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- Welch, Mary Scott (July 2, 1973). "Walking the City's Bridges". New York. p. 31. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- Petroff, John (August 27, 1973). "Bridge Bits" (letter to the editor)". New York. p. 5. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- "Welfare Island to be Restudied" (PDF). The New York Times. February 11, 1968. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- Ferretti, Fred (May 18, 1976). "Aerial Tram Ride to Roosevelt Island Is Opened With a Splash on O'Dwyer". The New York Times. p. 69. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Lorch, Donatella (October 29, 1989). "The 'Subway to Nowhere' Now Goes Somewhere". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- Grynbaum, Michael M. (November 30, 2010). "Quirky Tram Runs Again, Delighting Its Riders". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Babin, Janet (August 2, 2011). "Park Reopens on Roosevelt Island". WNYC. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- Pérez-Peña, Richard (December 19, 2011). "Cornell Bid Formally Chosen for Science School in City". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- Brooks, Stan "Mayor Bloomberg: New York City Ready To Declare War On Silicon Valley" Archived January 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine "CBS New York" (December 19, 2011)

- Foderaro, Lisa W (October 17, 2012). "Dedicating Park to Roosevelt and His View of Freedom". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- Jamerson, Joshua (June 13, 2015). "Roosevelt Island Awakens to a Clinton Crowd". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

Though the usual early-morning risers were already walking their dogs and stretching their legs as they strolled along the East River, this was not a typical Saturday on Roosevelt Island. At the southern end of the island, the residents found themselves bumping into hundreds of supporters of Hillary Rodham Clinton waiting in line hours before she was expected to give the kickoff speech of her 2016 campaign for president here.... The campaign was handing out tickets to the event to people standing in a line near Four Freedoms Park, which celebrates the famous speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

- "Roosevelt Island Campus Project". Cornell University. March 17, 2014. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- Zimmer, Amy (May 3, 2012). "Hospital patients forced out as Roosevelt Island tech campus moves in". dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Harris, Elizabeth A. (September 13, 2017). "High Tech and High Design, Cornell's Roosevelt Island Campus Opens". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- "Nellie Bly Memorial Call for Artists". Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of New York. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- "Amanda Matthews of Prometheus Art Selected to Create Monument to Journalist Nelly Bly on Roosevelt Island" (Press release). Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of New York. October 16, 2019. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- "Installation". The Girl Puzzle. Prometheus Art. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- "Riverwalk Crossing Luxury Apartments on NYC's Roosevelt Island". riverwalknyc.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- "Riverwalk on Roosevelt Island". hudsoninc.com. Hudson, Inc. Archived from the original on June 1, 2015. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- Foderaro, Lisa W. (October 16, 2012). "A Monument to Roosevelt, on the Eve of Dedication, Is Mired in a Dispute With Donors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Ilnytzy, Ula (October 17, 2012). "Decades late, FDR memorial park dedicated in NYC". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Clark, Roger (November 30, 2010). "Roosevelt Island Tram Once Again Running Over The East River". NY1. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- "You are cordially Invited to the Grand Reopening of the Roosevelt Island Aerial Tramway" (PDF). rioc.com. Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation. November 24, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- Lynch, Andrew (2020). "New York City Subway Track Map" (PDF). vanshnookenraggen.com. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- "Routes and Schedules: Astoria". ferry.nyc. NYC Ferry by Hornblower. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Barone, Vin (August 28, 2017). "Astoria's NYC Ferry route launches Tuesday". am New York. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Evelly, Jeanmarie (August 29, 2017). "SEE IT: NYC Ferry Service Launches New Astoria Route". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Ganeeva, Anastasiya (May 30, 2013). "Economic, Racial & Religious Diversity on Roosevelt Island". The Stewardship Report. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014.

- Janet, Spencer King (March 15, 2012). "A life on Roosevelt Island". Cornell Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "Roosevelt Island Islamic Society Has New Home - Signed Lease For Former Cabrini Chapel Space Says Hudson Related". Roosevelt Islander. January 24, 2019. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "Chabad @ Cornell Tech". Chabad of Roosevelt Island. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Yu, Alan (April 10, 2017). "How Chinese student boom has kept US public universities afloat, and why Trump's America First stance might affect that". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "The Most Chinese Schools in America". Foreign Policy. January 4, 2016. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Chester, Ken (May 10, 2018). "Can China's 'WeChat Diaspora' Pioneer Mobile Payment in the US?". Sixth Tone. Archived from the original on May 10, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Campbell, Kyle (October 9, 2018). "Hot-pot joint signs lease on Roosevelt Island Main Street". Real Estate Weekly. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- "欢迎加入我们的主日崇拜". Hope Covenant Church. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Find Locations: Roosevelt Island". usps.com. United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Mason, Betsy (August 16, 2010). "New York City's Trash-Sucking Island". WIRED. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- Chaban, Matt A.V. (August 3, 2015). "Garbage Collection, Without the Noise or the Smell". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

While vehicles still found their way onto the island, garbage trucks were largely banished, thanks to the pneumatic tube system, one of the largest in the world. It sucks up roughly 10 tons of trash from the island's 12,000 residents each day.... After they drop garbage down chutes in their buildings, it collects at the bottom until a trapdoor is activated, releasing the waste into 22-inch-wide red steel tubes that run underground.

- Bodarky, George (July 26, 2017). "How New York's Roosevelt Island Sucks Away Summer Trash Stink". NPR. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- "Locals, lawmakers push to reopen Long Island City firehouse". FOX 5 New York. August 23, 2019. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- Cooper, Michael (May 22, 2003). "Six Firehouses Receive Order to Close by Sunday Morning, as Lawsuit to Save Them Proceeds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- Cardwell, Diane (May 29, 2003). "Metro Briefing | New York: Brooklyn: Judge Rules On Firehouse". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- Archibold, Randal C. (July 3, 2003). "Judge Says Closing of Queens Firehouse Is Illegal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- "Fields | Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of the State of New York". rioc.ny.gov. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- "Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of the State of New York". Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Dowling, Rachel (October 8, 2019). "Octagon Field Renamed McManus, Tensions Remain". The Main Street Wire. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

Last week, over a year after its abrupt closure last August, the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation (RIOC) re-opened Octagon Field and re-naming it Jack McManus Field in honor of the recently retired Chief of the Island's Public Safety Department (PSD).

- "Section O: Environmental Conservation and Recreation, Table O-9". 2014 New York State Statistical Yearbook (PDF). The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government. 2014. p. 672. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Foderaro, Lisa W. (October 17, 2012). "Dedicating Park to Roosevelt and His View of Freedom". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- "Experience Southpoint Park | Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of the State of New York". rioc.ny.gov. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- "BBQ in Lighthouse Park | Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of the State of New York". rioc.ny.gov. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- "Waterfront Access Map". www1.nyc.gov. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Warerkar, Tanay (June 5, 2017). "Cornell Tech's Roosevelt Island campus readies for its September debut". Curbed New York. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Nonko, Emily (March 12, 2018). "Construction begins on Snøhetta-designed hotel on Roosevelt Island". Curbed New York. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "About the Roosevelt Island Library". The New York Public Library. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- Farrell, William E. (February 4, 1981). "About New York; Two Who Created a Library on Roosevelt Island". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Weaver, Shaye (January 25, 2021). "See inside the stunning new public library coming to Roosevelt Island". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- Garber, Nick (January 25, 2021). "Roosevelt Island Public Library Opens After Years Of Work". Upper East Side, NY Patch. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- "Literary Landmark: Roosevelt Island Branch, New York Public Library - various". United for Libraries. October 19, 2016. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "Roosevelt Island Garden Club". Roosevelt Island Garden Club. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "The Roosevelt Island Daily". rooseveltislanddaily.prosepoint.net. David Stone. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- "Blog". Roosevelt Islander Online. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- Timothy J. Gilfoyle (2006). A Pickpocket's Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. W. W. Norton Company. ISBN 978-0393329896.

- "Free Becky Edelson; Funeral Plans Off". The New York Times. August 21, 1914. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- "The "Man-Monster" by Jonathan Ned Katz · Peter Sewally/Mary Jones, June 11, 1836 · OutHistory: It's About Time". outhistory.org. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "4 in Cowboy Gang Up for Pleading". New York Daily News. October 28, 1925. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bechet, Matilde (February 27, 2019). "Senior composes and plans original musical". The Ithacan. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Though a musical seems grandiose and monumental under the pageantry of performance and bright stage lights, every production begins with just an idea. For senior Jonah Bobo, the idea for him to write his own musical came nearly three years ago.... Hayat, a playwright and graduate from SUNY Purchase, grew up in Roosevelt Island, New York, a few houses down from Bobo, her brother's friend.

- Cohen, Joshua (April 2008). "The Bank Teller's Game - Michael Brodsky". Zeek. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Called by Library Journal 'one of the most important writers working today,' Michael Brodsky is very much a writer for an idealized tomorrow. He was born in the Bronx in 1951, and lives in the seclusion nearest to Manhattan, namely Roosevelt Island.

- "Biography". The History Makers. June 17, 2019. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- Karmin, Craig (July 23, 2010). "Roosevelt Island Pitch: Better than the 'Burbs". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- Insunza, Andrea; Ortega, Javier (October 24, 2013). "Cuánto ha cambiado Bachelet". Qué Pasa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Ashley, Dottie (October 12, 1977). "Playwright Comes 'Home'". The Columbia Record. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

Ms Childress now lives on the recently renewed Roosevelt Island a small community of modern apartment buildings and swimming pools in the middle of Manhattan's East River.

- "Billy, Coleen address 'racist' prenup photos". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. March 12, 2018. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Crawford also assured the public that he is familiar with racism, and said they mean no harm. 'I grew up in a very diverse city (Roosevelt Island), and had experienced bullying and racism in my youth because of my being "an Asian." Trust me, we meant no harm,' he said.

- "Mike Epps Unleashes His Wrath On A Heckler!!". Hip Hop News Uncensored. August 2, 2018. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Epps was born on November 18, 1970 in Indianapolis, Indiana. Epps family moved to Roosevelt Island, New York when he was young.

- "Thank You Letters of Secretary-General to Goodwill Ambassadors" (PDF). United Nations Archives Search Engine. United Nations Archives and Records Management Section. November 10, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

Ms. Wendy Fitzwilliam 40 River Road #16J Roosevelt Island, NY 10044

- Dyer, Richard (December 31, 2004). "Soprano Amanda Forsythe voices her love of opera". The Boston Herald. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Forsythe was elegant, poised, focused, and determined as she talked recently about her emerging career. She grew up on Roosevelt Island, alongside Manhattan, and sang in high school choirs without ever taking her vocal potential very seriously.

- Trott, William C. (August 13, 1986). "Hackett Goes To Sea". United Press International. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Buddy Hackett loves his Roosevelt Island. He got up early Tuesday to be on the maiden voyage of a ferry that runs from the island down the East River to Wall Street on Manhattan. The rotund comedian lives on Roosevelt when in New York City and said he wanted to be on the ferry's 'maiden voyage because I want to go down in history like Christopher Columbus.'

- Hooper, Joshua (November 25, 2009). "Tim Keller Wants to Save Your Yuppie Soul". New York. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

On a sunny morning not long ago, Keller greets me at his upper-floor apartment on Roosevelt Island and ushers me into his study.

- Homme, Alexander (October 30, 2009). "Roosevelt Island". Manhattan Style. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011.

Al Lewis was also known as the unofficial mayor of Roosevelt Island

- Senft, Bret (September 23, 2006). "With Style, a Goodbye to Grampa Al". The Main Street Wire. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014.

- Nussbaum, Emily (May 2, 2008). "How 'Sex and the City' Made Sarah Jessica Parker the Poster Girl for the New Manhattan -- New York Magazine - Nymag". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- Glazer, Eliot (October 11, 2007). "Inside With: Andrea Rosen". The Apiary. Archived from the original on February 10, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- Brown, David (May 18, 2018). "AA Q&A: Jon Sciambi talks baseball, redheads, the ESPN TV job he didn't get and the ALS charity he helped to start". Awful Announcing. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

Jon Sciambi grew up in a unique part of New York City, playing ball on tiny Roosevelt Island and rooting for the Philadelphia Phillies.

- Ross, Barbara (August 31, 2016). "Victoria's Secret model being sued for 'misleading' Airbnb listing defends her Roosevelt Island apartment". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

That's what a Victoria's Secret model insisted Wednesday about her Roosevelt Island apartment that was the subject of a new lawsuit by an unhappy Airbnb customer. However, the model, Lyndsey Scott, said she 'acknowledges' the complaints of attorney Christian Pugaczewski and is 'working closely with Airbnb to ensure that this is settled in a fair and just manner.'

- McKinley Jr., James C. (June 21, 2017). "First Openly Gay Judge Confirmed for New York's Highest Court". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

So the choice of Paul G. Feinman, an associate justice of the Appellate Division of the State Supreme Court in Manhattan, to fill the seat left open by the death of Judge Sheila Abdus-Salaam in April was a watershed for gay New Yorkers.... Justice Feinman and his husband, Robert Ostergaard, a web publisher, live on Roosevelt Island.

- Blackwell's Island at IMDb

- Kermode, Mark (2008). The Exorcist. BFI Modern Classics. British Film Institute. p. 42. ISBN 9780851709673.

- "Comics:Amazing Spider-Man Vol 1 162". Marvel Database Project.

- Shrestha, Naman. "Where Was John Wick 4 Filmed?" Archived March 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, The Cinemaholic, March 21, 2023. Accessed March 26, 2023. "Additional portions for John Wick: Chapter 4 were lensed in and around New York City as the production team made the most of the Big Apple’s locales. Specifically, Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms State Park at 1 FDR Four Freedoms in NYC’s Roosevelt Island features in one of the essential portions of the movie."

- Courrier, Kevin; Green, Susan (1999). Law & Order: The Unofficial Companion -- Updated and Expanded. Macmillan. p. 213. ISBN 9781580631082. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Pavlica, Carissa (October 26, 2016). "Younger Season 3 Episode 5 Review: P Is For Pancake". TV Fanatic. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- Cousido, Pablo (2013). Nueva York Impactante (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Recorriendo Destinos. p. 155. ISBN 9781291242195.

- Alexander, Peter. "King Kong: The Monster Who Created Universal Studios Florida". Totally Fun Company. Archived from the original on October 10, 2013.

External links

RIOC:

- Official website for RIOC, Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation

- Parks & Recreation Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation's website for Events, memberships, permits

- Roosevelt Island Residents Association

Community resources, news, events, issues:

- The Main Street WIRE

- Roosevelt Islander, blog by Rick O'Conor

Other:

- Roosevelt Island 360

- 1903 Panorama of Blackwell's Island, N.Y., Library of Congress, Thomas A. Edison motion picture

- The Island Nobody Knows, a fully digitized exhibition catalog about Roosevelt Island from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

_crop.jpg.webp)