Rocky Mountains

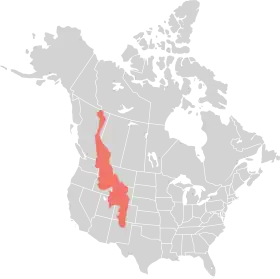

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers)[2] in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in the southwestern United States. Depending on differing definitions between Canada and the U.S., its northern terminus is located either in northern British Columbia's Terminal Range south of the Liard River and east of the Trench, or in the northeastern foothills of the Brooks Range/British Mountains that face the Beaufort Sea coasts between the Canning River and the Firth River across the Alaska-Yukon border.[3] Its southernmost point is near the Albuquerque area adjacent to the Rio Grande rift and north of the Sandia–Manzano Mountain Range. Being the easternmost portion of the North American Cordillera, the Rockies are distinct from the tectonically younger Cascade Range and Sierra Nevada, which both lie farther to its west.

| Rocky Mountains | |

|---|---|

| The Rockies (en), Les montagnes Rocheuses (fr), Montañas Rocosas, Rocallosas (es) | |

Moraine Lake and the Valley of the Ten Peaks, Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Elbert, CO |

| Elevation | 14,440 feet (4401.2 m)[1] |

| Coordinates | 39°07′03.9″N 106°26′43.2″W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 4,828 km (3,000 mi)(straight-line distance) |

| Width | 650 km (400 mi) |

| Geography | |

| |

| Countries |

|

| Provinces/States | |

| Range coordinates | 43°44′28″N 110°48′07″W |

| Parent range | North American Cordillera |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Precambrian and Cretaceous |

| Type of rock | |

The Rockies formed 55 million to 80 million years ago during the Laramide orogeny, in which a number of plates began sliding underneath the North American plate. The angle of subduction was shallow, resulting in a broad belt of mountains running down western North America. Since then, further tectonic activity and erosion by glaciers have sculpted the Rockies into dramatic peaks and valleys. At the end of the last ice age, humans began inhabiting the mountain range. After explorations of the range by Europeans, such as Sir Alexander Mackenzie, and Anglo-Americans, such as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, natural resources such as minerals and fur drove the initial economic exploitation of the mountains, although the range itself never experienced a dense population.

Of the 100 highest major peaks of the Rocky Mountains, 78 (including the 30 highest) are in Colorado, ten in Wyoming, six in New Mexico, three in Montana, and one each in Utah, British Columbia, and Idaho. Of the 50 most prominent summits of the Rocky Mountains, 12 are in British Columbia,[lower-alpha 1] 12 in Montana, ten in Alberta,[lower-alpha 1] eight in Colorado, four in Wyoming, three in Utah, three in Idaho, and one in New Mexico. Public parks and forest lands protect much of the mountain range, and they are popular tourist destinations, especially for hiking, camping, mountaineering, fishing, hunting, mountain biking, snowmobiling, skiing, and snowboarding.

Etymology

The name of the mountains is a translation of an Amerindian Algonquian name, specifically Cree ᐊᓯᐣᐘᑎ asin-wati (originally transcribed as-sin-wati), literally "rocky mountain". The first mention of their present name by a European was in the journal of Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre in 1752, where they were called "Montagnes de Roche".[4][5] Another name given to the place by the Cree is ᐊᓭᓂᐓᒉ Aseniwuche.

Geography

The Rocky Mountains are the easternmost portion of the expansive North American Cordillera. They are often defined as stretching from the Liard River in British Columbia[6]: 13 south to the headwaters of the Pecos River, a tributary of the Rio Grande, in New Mexico. The Rockies vary in width from 110 to 480 kilometres (70 to 300 miles). The Rocky Mountains contain the highest peaks in central North America. The range's highest peak is Mount Elbert in Colorado at 4,401 metres (14,440 feet) above sea level. Mount Robson in British Columbia, at 3,954 m (12,972 ft), is the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies.

The eastern edge of the Rockies rises dramatically above the Interior Plains of central North America, including the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico and Colorado, the Front Range of Colorado, the Wind River Range and Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming, the Absaroka-Beartooth ranges and Rocky Mountain Front of Montana and the Clark Range of Alberta.

Central ranges of the Rockies include the La Sal Range along the Utah-Colorado border, the Abajo Mountains and Henry Mountains of Southeastern Utah, the Uinta Range of Utah and Wyoming, and the Teton Range of Wyoming and Idaho.

The western edge of the Rockies includes ranges such as the Wasatch near Salt Lake City, the San Juan Mountains of New Mexico and Colorado, the Bitterroots along the Idaho-Montana border, and the Sawtooths in central Idaho. The Great Basin and Columbia River Plateau separate these subranges from distinct ranges further to the west. In Canada, the western edge of the Rockies is formed by the huge Rocky Mountain Trench, which runs the length of British Columbia from its beginning as the Kechika Valley on the south bank of the Liard River, to the middle Lake Koocanusa valley in northwestern Montana.[7]

The Canadian Rockies are defined by Canadian geographers as everything south of the Liard River and east of the Rocky Mountain Trench, and do not extend into Yukon, Northwest Territories or central British Columbia. They are divided into three main groups: the Muskwa Ranges, Hart Ranges (collectively called the Northern Rockies) and Continental Ranges. Other more northerly mountain ranges of the eastern Canadian Cordillera continue beyond the Liard River valley, including the Selwyn, Mackenzie and Richardson Mountains in Yukon as well as the British Mountains/Brooks Range in Alaska, but those are not officially recognized as part of the Rockies by the Geological Survey of Canada, although the Geological Society of America definition does consider them parts of the Rocky Mountains system as the "Arctic Rockies".[3]

The Continental Divide of the Americas is in the Rocky Mountains and designates the line at which waters flow either to the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. Triple Divide Peak (2,440 m or 8,020 ft) in Glacier National Park is so named because water falling on the mountain reaches not only the Atlantic and Pacific but Hudson Bay as well. Farther north in Alberta, the Athabasca and other rivers feed the basin of the Mackenzie River, which has its outlet on the Beaufort Sea of the Arctic Ocean.

Human population is not very dense in the Rockies, with an average of four people per square kilometer and few cities with over 50,000 people. However, the human population grew rapidly in the Rocky Mountain states between 1950 and 1990. The forty-year statewide increases in population range from 35% in Montana to about 150% in Utah and Colorado. The populations of several mountain towns and communities have doubled in the forty years 1972–2012. Jackson, Wyoming, increased 260%, from 1,244 to 4,472 residents, in those forty years.[8]

Geology

The rocks in the Rocky Mountains were formed before the mountains were raised by tectonic forces. The oldest rock is Precambrian metamorphic rock that forms the core of the North American continent. There is also Precambrian sedimentary argillite, dating back to 1.7 billion years ago. During the Paleozoic, western North America lay underneath a shallow sea, which deposited many kilometers of limestone and dolomite.[6]: 76

In the southern Rockies, near present-day Colorado, these ancestral rocks were disturbed by mountain building approximately 300 Ma, during the Pennsylvanian. This mountain-building produced the Ancestral Rocky Mountains. They consisted largely of Precambrian metamorphic rock forced upward through layers of the limestone laid down in the shallow sea.[9] The mountains eroded throughout the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic, leaving extensive deposits of sedimentary rock.

Terranes began colliding with the western edge of North America in the Mississippian (approximately 350 million years ago), causing the Antler orogeny.[10] For 270 million years, the focus of the effects of plate collisions were near the edge of the North American plate boundary, far to the west of the Rocky Mountain region.[10] It was not until 80 Ma these effects began reaching the Rockies.[11]

The current Rocky Mountains arose in the Laramide orogeny from between 80 and 55 Ma.[11] For the Canadian Rockies, the mountain building is analogous to pushing a rug on a hardwood floor:[12]: 78 the rug bunches up and forms wrinkles (mountains). In Canada, the terranes and subduction are the foot pushing the rug, the ancestral rocks are the rug, and the Canadian Shield in the middle of the continent is the hardwood floor.[12]: 78

Further south, an unusual subduction may have caused the growth of the Rocky Mountains in the United States, where the Farallon plate dove at a shallow angle below the North American plate. This low angle moved the focus of melting and mountain building much farther inland than the normal 300 to 500 kilometres (200 to 300 mi). Scientists hypothesize that the shallow angle of the subducting plate increased the friction and other interactions with the thick continental mass above it. Tremendous thrusts piled sheets of crust on top of each other, building the broad, high Rocky Mountain range.[13]

The current southern Rockies were forced upwards through the layers of Pennsylvanian and Permian sedimentary remnants of the Ancestral Rocky Mountains.[14] Such sedimentary remnants were often tilted at steep angles along the flanks of the modern range; they are now visible in many places throughout the Rockies, and are shown along the Dakota Hogback, an early Cretaceous sandstone formation running along the eastern flank of the modern Rockies.

Just after the Laramide orogeny, the Rockies were like Tibet: a high plateau, probably 6,000 metres (20,000 ft) above sea level. In the last sixty million years, erosion stripped away the high rocks, revealing the ancestral rocks beneath, and forming the current landscape of the Rockies.[12]: 80–81

Periods of glaciation occurred from the Pleistocene Epoch (1.8 million – 70,000 years ago) to the Holocene Epoch (fewer than 11,000 years ago). These ice ages left their mark on the Rockies, forming extensive glacial landforms, such as U-shaped valleys and cirques. Recent glacial episodes included the Bull Lake Glaciation, which began about 150,000 years ago, and the Pinedale Glaciation, which perhaps remained at full glaciation until 15,000–20,000 years ago.[15]

All of these geological processes exposed a complex set of rocks at the surface. For example, volcanic rock from the Paleogene and Neogene periods (66 million – 2.6 million years ago) occurs in the San Juan Mountains and in other areas. Millennia of severe erosion in the Wyoming Basin transformed intermountain basins into a relatively flat terrain. The Tetons and other north-central ranges contain folded and faulted rocks of Paleozoic and Mesozoic age draped above cores of Proterozoic and Archean igneous and metamorphic rocks ranging in age from 1.2 billion (e.g., Tetons) to more than 3.3 billion years (Beartooth Mountains).[8]

Ecology and climate

There are a wide range of environmental factors in the Rocky Mountains. The Rockies range in latitude between the Liard River in British Columbia (at 59° N) and the Rio Grande in New Mexico (at 35° N). Prairie occurs at or below 550 metres (1,800 ft), while the highest peak in the range is Mount Elbert at 4,400 metres (14,440 ft). Precipitation ranges from 250 millimetres (10 in) per year in the southern valleys[16] to 1,500 millimetres (60 in) per year locally in the northern peaks.[17] Average January temperatures can range from −7 °C (20 °F) in Prince George, British Columbia, to 6 °C (43 °F) in Trinidad, Colorado.[18] Therefore, there is no single monolithic ecosystem for the entire Rocky Mountain Range.

Instead, ecologists divide the Rockies into a number of biotic zones. Each zone is defined by whether it can support trees and the presence of one or more indicator species. Two zones that do not support trees are the Plains and the Alpine tundra. The Great Plains lie to the east of the Rockies and is characterized by prairie grasses (below roughly 550 m or 1,800 ft). Alpine tundra occurs in regions above the tree-line for the Rocky Mountains, which varies from 3,700 m (12,000 ft) in New Mexico to 760 m (2,500 ft) at the northern end of the Rockies (near the Yukon).[18]

The U.S. Geological Survey defines ten forested zones in the Rockies. Zones in more southern, warmer, or drier areas are defined by the presence of pinyon pines/junipers, ponderosa pines, or oaks mixed with pines. In more northern, colder, or wetter areas, zones are defined by Douglas firs, Cascadian species (such as western hemlock), lodgepole pines/quaking aspens, or firs mixed with spruce. Near tree-line, zones can consist of white pines (such as whitebark pine or bristlecone pine); or a mixture of white pine, fir, and spruce that appear as shrub-like krummholz. Finally, rivers and canyons can create a unique forest zone in more arid parts of the mountain range.[8]

The Rocky Mountains are an important habitat for a great deal of well-known wildlife, such as wolves, elk, moose, mule and white-tailed deer, pronghorn, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, badgers, black bears, grizzly bears, coyotes, lynxes, cougars, and wolverines.[8][19] North America's largest herds of elk are in the Alberta–British Columbia foothills forests.

The status of most species in the Rocky Mountains is unknown, due to incomplete information. European-American settlement of the mountains has adversely impacted native species. Examples of some species that have declined include western toads, greenback cutthroat trout, white sturgeon, white-tailed ptarmigan, trumpeter swan, and bighorn sheep. In the U.S. portion of the mountain range, apex predators such as grizzly bears and wolf packs had been extirpated from their original ranges, but have partially recovered due to conservation measures and reintroduction. Other recovering species include the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon.[8]

History

Indigenous people

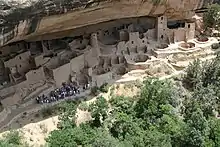

Since the last great ice age, the Rocky Mountains were home first to indigenous peoples including the Apache, Arapaho, Bannock, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Coeur d'Alene, Kalispel, Crow Nation, Flathead, Shoshone, Sioux, Ute, Kutenai (Ktunaxa in Canada), Sekani, Dunne-za, and others. Paleo-Indians hunted the now-extinct mammoth and ancient bison (an animal 20% larger than modern bison) in the foothills and valleys of the mountains. Like the modern tribes that followed them, Paleo-Indians probably migrated to the plains in fall and winter for bison and to the mountains in spring and summer for fish, deer, elk, roots, and berries. In Colorado, along with the crest of the Continental Divide, rock walls that Native Americans built for driving game date back 5,400–5,800 years. A growing body of scientific evidence indicates that indigenous people had significant effects on mammal populations by hunting and on vegetation patterns through deliberate burning.[8]

European exploration

Recent human history of the Rocky Mountains is one of more rapid change. The Spanish explorer Francisco Vázquez de Coronado—with a group of soldiers and missionaries marched into the Rocky Mountain region from the south in 1540.[20] In 1610, the Spanish founded the city of Santa Fe, the oldest continuous seat of government in the United States, at the foot of the Rockies in present-day New Mexico. The introduction of the horse, metal tools, rifles, new diseases, and different cultures profoundly changed the Native American cultures. Native American populations were extirpated from most of their historical ranges by disease, warfare, habitat loss (eradication of the bison), and continued assaults on their culture.[8]

In 1739, French fur traders Pierre and Paul Mallet, while journeying through the Great Plains, discovered a range of mountains at the headwaters of the Platte River, which local American Indian tribes called the "Rockies", becoming the first Europeans to report on this uncharted mountain range.[21]

.jpg.webp)

Sir Alexander Mackenzie (1764 – March 11, 1820) became the first European to cross the Rocky Mountains in 1793.[22] He found the upper reaches of the Fraser River and reached the Pacific coast of what is now Canada on July 20 of that year, completing the first recorded transcontinental crossing of North America north of Mexico.[23] He arrived at Bella Coola, British Columbia, where he first reached saltwater at South Bentinck Arm, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) was the first scientific reconnaissance of the Rocky Mountains.[24] Specimens were collected for contemporary botanists, zoologists, and geologists. The expedition was said to have paved the way to (and through) the Rocky Mountains for European-Americans from the East, although Lewis and Clark met at least 11 European-American mountain men during their travels.[8]

Mountain men, primarily French, Spanish, and British, roamed the Rocky Mountains from 1720 to 1800 seeking mineral deposits and furs. The fur-trading North West Company established Rocky Mountain House as a trading post in what is now the Rocky Mountain Foothills of present-day Alberta in 1799, and their business rivals the Hudson's Bay Company established Acton House nearby.[25] These posts served as bases for most European activity in the Canadian Rockies in the early 19th century. Among the most notable are the expeditions of David Thompson, who followed the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean.[26] On his 1811 expedition, he camped at the junction of the Columbia River and the Snake River and erected a pole and notice claiming the area for the United Kingdom and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a fort at the site.[27]

By the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which established the 49th parallel north as the international boundary west from Lake of the Woods to the "Stony Mountains";[28] the UK and the US agreed to what has since been described as "joint occupancy" of lands further west to the Pacific Ocean. Resolution of the territorial and treaty issues, the Oregon dispute, was deferred until a later time.

In 1819, Spain ceded their rights north of the 42nd Parallel to the United States, though these rights did not include possession and also included obligations to Britain and Russia concerning their claims in the same region.

Settlement

After 1802, fur traders and explorers ushered in the first widespread American presence in the Rockies south of the 49th parallel. The more famous of these include William Henry Ashley, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, John Colter, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Andrew Henry, and Jedediah Smith. On July 24, 1832, Benjamin Bonneville led the first wagon train across the Rocky Mountains by using South Pass in the present State of Wyoming.[8] Similarly, in the wake of Mackenzie's 1793 expedition, fur trading posts were established west of the Northern Rockies in a region of the northern Interior Plateau of British Columbia which came to be known as New Caledonia, beginning with Fort McLeod (today's community of McLeod Lake) and Fort Fraser, but ultimately focused on Stuart Lake Post (today's Fort St. James).

Negotiations between the United Kingdom and the United States over the next few decades failed to settle upon a compromise boundary and the Oregon Dispute became important in geopolitical diplomacy between the British Empire and the new American Republic. In 1841, James Sinclair, Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company, guided some 200 settlers from the Red River Colony west to bolster settlement around Fort Vancouver in an attempt to retain the Columbia District for Britain. The party crossed the Rockies into the Columbia Valley, a region of the Rocky Mountain Trench near present-day Radium Hot Springs, British Columbia, then traveled south. Despite such efforts, in 1846, Britain ceded all claim to Columbia District lands south of the 49th parallel to the United States; as resolution to the Oregon boundary dispute by the Oregon Treaty.[29]

Thousands passed through the Rocky Mountains on the Oregon Trail beginning in the 1840s.[30] The Mormons began settling near the Great Salt Lake in 1847.[31] From 1859 to 1864, gold was discovered in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia, sparking several gold rushes bringing thousands of prospectors and miners to explore every mountain and canyon and to create the Rocky Mountains' first major industry. The Idaho gold rush alone produced more gold than the California and Alaska gold rushes combined and was important in the financing of the Union Army during the American Civil War. The transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869,[32] and Yellowstone National Park was established as the world's first national park in 1872.[33] Meanwhile, a transcontinental railroad in Canada was originally promised in 1871. Though political complications pushed its completion to 1885, the Canadian Pacific Railway eventually followed the Kicking Horse and Rogers Passes to the Pacific Ocean.[34] Canadian railway officials also convinced Parliament to set aside vast areas of the Canadian Rockies as Jasper, Banff, Yoho, and Waterton Lakes National Parks, laying the foundation for a tourism industry which thrives to this day. Glacier National Park (MT) was established with a similar relationship to tourism promotions by the Great Northern Railway.[35] While settlers filled the valleys and mining towns, conservation and preservation ethics began to take hold. U.S. President Harrison established several forest reserves in the Rocky Mountains in 1891–1892. In 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt extended the Medicine Bow Forest Reserve to include the area now managed as Rocky Mountain National Park. Economic development began to center on mining, forestry, agriculture, and recreation, as well as on the service industries that support them. Tents and camps became ranches and farms, forts and train stations became towns, and some towns became cities.[8]

Economy

Industry and development

Economic resources of the Rocky Mountains are varied and abundant. Minerals found in the Rocky Mountains include significant deposits of copper, gold, lead, molybdenum, silver, tungsten, and zinc. The Wyoming Basin and several smaller areas contain significant reserves of coal, natural gas, oil shale, and petroleum. For example, the Climax mine, near Leadville, Colorado, was the largest producer of molybdenum in the world. Molybdenum is used in heat-resistant steel in such things as cars and planes. The Climax mine employed over 3,000 workers. The Coeur d'Alene mine of northern Idaho produces silver, lead, and zinc. Canada's largest coal mines are near Fernie, British Columbia and Sparwood, British Columbia; additional coal mines exist near Hinton, Alberta, and in the Northern Rockies surrounding Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia.[8]

Abandoned mines with their wakes of mine tailings and toxic wastes dot the Rocky Mountain landscape. In one major example, eighty years of zinc mining profoundly polluted the river and bank near Eagle River in north-central Colorado. High concentrations of the metal carried by spring runoff harmed algae, moss, and trout populations. An economic analysis of mining effects at this site revealed declining property values, degraded water quality, and the loss of recreational opportunities. The analysis also revealed that cleanup of the river could yield $2.3 million in additional revenue from recreation. In 1983, the former owner of the zinc mine was sued by the Colorado Attorney General for the $4.8 million cleanup costs; five years later, ecological recovery was considerable.[8][36]

The Rocky Mountains contain several sedimentary basins that are rich in coalbed methane. Coalbed methane is natural gas that arises from coal, either through bacterial action or through exposure to high temperature. Coalbed methane supplies 7 percent of the natural gas used in the U.S. The largest coalbed methane sources in the Rocky Mountains are in the San Juan Basin in New Mexico and Colorado and the Powder River Basin in Wyoming. These two basins are estimated to contain 38 trillion cubic feet of gas. Coalbed methane can be recovered by dewatering the coal bed, and separating the gas from the water; or injecting water to fracture the coal to release the gas (so-called hydraulic fracturing).[37]

Agriculture and forestry are major industries. Agriculture includes dryland and irrigated farming and livestock grazing. Livestock are frequently moved between high-elevation summer pastures and low-elevation winter pastures, a practice known as transhumance.[8]

Tourism

Every year the scenic areas of the Rocky Mountains draw millions of tourists.[8] The main language of the Rocky Mountains is English. But there are also linguistic pockets of Spanish and indigenous languages.

People from all over the world visit the sites to hike, camp, or engage in mountain sports.[8][38] In the summer season, examples of tourist attractions are:

In the United States:

- Yellowstone National Park

- Glacier National Park

- Grand Teton National Park

- Rocky Mountain National Park

- Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

- Sawtooth National Recreation Area

- Flathead Lake

In Canada, the mountain range contains these national parks:

- Banff National Park

- Jasper National Park

- Kootenay National Park

- Waterton Lakes National Park

- Yoho National Park

Glacier National Park in Montana and Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta border each other and are collectively known as Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park.

In the winter, skiing is the main attraction, with dozens of Rocky Mountain ski areas and resorts.

The adjacent Columbia Mountains in British Columbia contain major resorts such as Panorama and Kicking Horse, as well as Mount Revelstoke National Park and Glacier National Park.

There are numerous provincial parks in the British Columbia Rockies, the largest and most notable being Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park, Mount Robson Provincial Park, Northern Rocky Mountains Provincial Park, Kwadacha Wilderness Provincial Park, Stone Mountain Provincial Park and Muncho Lake Provincial Park.

John Denver wrote the song Rocky Mountain High in 1972. The song is one of the two official state songs of Colorado.[39][40]

Hazards

Encountering bears or mountain lions (cougars) is a concern in the Rocky Mountains.[41][42] There are other concerns as well, including bugs, wildfires, adverse snow conditions and nighttime cold temperatures.[43]

Importantly, there have been notable incidents in the Rocky Mountains, including accidental deaths, due to falls from steep cliffs (a misstep could be fatal in this class 4/5 terrain) and due to falling rocks, over the years, including 1993,[44] 2007 (involving an experienced NOLS leader),[45] 2015[46] and 2018.[47] Other incidents include a seriously injured backpacker being airlifted near SquareTop Mountain[48] in 2005,[49] and a fatal hiker incident (from an apparent accidental fall) in 2006 that involved state search and rescue.[50] The U.S. Forest Service does not offer updated aggregated records on the official number of fatalities in the Rocky Mountains.

See also

- Arabian Rocky Mountains

- Hazards in the Wind River Range

- List of mountain peaks of the Rocky Mountains

- Little Rocky Mountains, mountain range in north-central Montana

- Rocky Mountains subalpine zone

- Southern Rocky Mountains

Notes

- Three of these peaks lie on the Alberta-British Columbia border.

References

- "MOUNT ELBERT". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- "Rocky Mountains | Location, Map, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Madole, Richard F.; Bradley, William C.; Loewenherz, Deborah S.; Ritter, Dale F.; Rutter, Nathaniel W.; Thorn, Colin E. (1987). "Rocky Mountains". In Graf, William L. (ed.). Geomorphic Systems of North America. Decade of North American Geology. Vol. 2 (Centennial Special ed.). Geological Society of America (published January 1, 1987). pp. 211–257. doi:10.1130/DNAG-CENT-v2.211. ISBN 9780813754147. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- Ak rigg, G.P.V.; Akrigg, Helen B. (1997). British Columbia Place Names (3rd ed.). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-7748-0636-7. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- Mardon, Ernest G.; Mardon, Austin A. (2010). Community Place Names of Alberta (3rd ed.). Edmonton, AB: Golden Meteorite Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-897472-17-0. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- Gadd, Ben (1995). Handbook of the Canadian Rockies. Corax Press. ISBN 9780969263111.

- Cannings, Richard (2007). The Rockies: A Natural History. Greystone/David Suzuki Foundation. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-55365-285-4.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from Stohlgren, TJ. "Rocky Mountains". Status and Trends of the Nation's Biological Resources. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006.

This article incorporates public domain material from Stohlgren, TJ. "Rocky Mountains". Status and Trends of the Nation's Biological Resources. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. - Chronic, Halka (1980). Roadside Geology of Colorado. Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-105-3.

- Blakely, Ron. "Geologic History of Western US". Archived from the original on June 22, 2010.

- English, Joseph M.; Johnston, Stephen T. (2004). "The Laramide Orogeny: What Were the Driving Forces?" (PDF). International Geology Review. 46 (9): 833 838. Bibcode:2004IGRv...46..833E. doi:10.2747/0020-6814.46.9.833. S2CID 129901811. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 7, 2011.

- Gadd, Ben (2008). Canadian Rockies Geology Road Tours. Corax Press. ISBN 9780969263128.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from Geologic Provinces of the United States: Rocky Mountains. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 10, 2006.

This article incorporates public domain material from Geologic Provinces of the United States: Rocky Mountains. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 10, 2006. - Lindsey, D.A. (2010). "The geologic story of Colorado's Sangre de Cristo Range" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Circular 1349. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2017.

- Pierce, K.L. (1979). History and dynamics of glaciation in the northern Yellowstone National Park area. Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 1 90. Professional Paper 729-F.

- "Southern Rocky Mountains". Forest Encyclopedia Network. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- "Northern Rocky Mountains". Forest Encyclopedia Network. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Sheridan, Scott. "US & Canada: Rocky Mountains (Chapter 14)" (PDF). Geography of the United States and Canada course notes. Kent State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 1, 2006.

- "Rocky Mountains | mountains, North America". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Events in the West (1528–1536)". PBS. 2001. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "The West: Events from 1650 to 1800". PBS. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- "Mackenzie: 1789, 1792–1797". Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "First Crossing of North America National Historic Site of Canada". Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Lewis and Clark Expedition: Scientific Encounters". Archived from the original on April 9, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site of Canada". February 28, 2012. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Guide to the David Thompson Papers 1806–1845". 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- Oldham, kit (January 23, 2003). "David Thompson plants the British flag at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers on July 9, 1811". Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Treaties in Force" (PDF). November 1, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Historical Context and American Policy". Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Oregon Trail Interpretive Center". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "The Mormon Trail". Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "The Transcontinental Railroad". 2012. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Yellowstone National Park". April 4, 2012. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Canadian Pacific Railway". Archived from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Glaciers and Glacier National Park". 2011. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- Brandt, E. (1993). "How much is a gray wolf worth?". National Wildlife. 31: 412.

- "Coal-Bed Gas Resources of the Rocky Mountain Region". USGS. USGS fact sheet 158-02. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012.

- "Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Foundation. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Brown, Jennifer (March 12, 2007). ""Rocky Mountain High" now 2nd state song". The Denver Post. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- "State Songs". Colorado.gov. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- Staff (2023). "Rocky Mountain Hiking Trails - Hiker Safety Tips". RockyMountainHikingTrails.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Staff (April 24, 2017). "Bear Safety in Wyoming's Wind River Country". WindRiver.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Ballou, Dawn (July 27, 2005). "Wind River Range condition update - Fires, trails, bears, Continental Divide". PineDaleOnline News. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Staff (1993). "Falling Rock, Loose Rock, Failure to Test Holds, Wyoming, Wind River Range, Seneca Lake". American Alpine Club. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- MacDonald, Dougald (August 14, 2007). "Trundled Rock Kills NOLS Leader". Climbing. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Staff (December 9, 2015). "Officials rule Wind River Range climbing deaths accidental". Casper Star-Tribune. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Dayton, Kelsey (August 24, 2018). "Deadly underestimation". WyoFile News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Funk, Jason (2009). "Squaretop Mountain Rock Climbing". Mountain Project. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Staff (July 22, 2005). "Injured man rescued from Square Top Mtn - Tip-Top Search & Rescue helps 2 injured on the mountain". PineDaleOnline News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Staff (September 1, 2006). "Incident Reports - September, 2006 - Wind River Search". WildernessDoc.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

Further reading

- Baron, Jill (2002). Rocky Mountain futures: an ecological perspective. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-953-9.

- Newby, Rick (2004). The Rocky Mountain region. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32817-X.

External links

- Colorado Rockies Forests ecoregion images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- North Central Rockies Forests ecoregion images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- South Central Rockies Forests ecoregion images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- Sunset on the Top of the Rocky Mountains, CO, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Archived November 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine