Rokeby Venus

The Rokeby Venus (/ˈroʊkbi/ ROHK-bee; also known as The Toilet of Venus, Venus at her Mirror, Venus and Cupid; Spanish: La Venus del espejo) is a painting by Diego Velázquez, the leading artist of the Spanish Golden Age. Completed between 1647 and 1651,[3] and probably painted during the artist's visit to Italy, the work depicts the goddess Venus in a sensual pose, lying on a bed with her back facing the viewer, and looking into a mirror held by the Roman god of physical love, her son Cupid. The painting is in the National Gallery, London.

Numerous works, from the ancient to the baroque, have been cited as sources of inspiration for Velázquez. The nude Venuses of the Italian painters, such as Giorgione's Sleeping Venus (c. 1510) and Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538), were the main precedents. In this work, Velázquez combined two established poses for Venus: recumbent on a couch or a bed, and gazing at a mirror. She is often described as looking at herself in the mirror, although this is physically impossible since viewers can see her face reflected in their direction. This phenomenon is known as the Venus effect.[4] In a number of ways the painting represents a pictorial departure, through its central use of a mirror, and because it shows the body of Venus turned away from the observer of the painting.[5]

The Rokeby Venus is the only surviving female nude by Velázquez. Nudes were extremely rare in seventeenth-century Spanish art,[6] which was policed actively by members of the Spanish Inquisition. Despite this, nudes by foreign artists were keenly collected by the court circle, and this painting was hung in the houses of Spanish courtiers until 1813, when it was brought to England to hang in Rokeby Park, Yorkshire. In 1906, the painting was purchased by National Art Collections Fund for the National Gallery, London. Although it was attacked and badly damaged in 1914 by Canadian suffragette Mary Richardson, it soon was fully restored and returned to display.

Painting

Description

The Rokeby Venus depicts the Roman goddess of love, beauty and fertility reclining languidly on her bed, her back to the viewer—in Antiquity, portrayal of Venus from a back view was a common visual and literary erotic motif[8]—and her knees tucked. She is shown without the mythological paraphernalia normally included in depictions of the scene; jewellery, roses, and myrtle are all absent. Unlike most earlier portrayals of the goddess, which show her with blond hair, Velázquez's Venus is a brunette.[7] The female figure can be identified as Venus because of the presence of her son, Cupid.

Venus gazes into a mirror held by Cupid, who is without his usual bow and arrows. When the work was first inventoried, it was described as "a nude woman", probably owing to its controversial nature. Venus looks outward at the viewer of the painting[9] through her reflected image in the mirror. However, the image is blurred and reveals only a vague reflection of her facial characteristics; the reflected image of the head is much larger than it would be in reality.[10] The critic Natasha Wallace has speculated that Venus's indistinct face may be the key to the underlying meaning of the painting, in that "it is not intended as a specific female nude, nor even as a portrayal of Venus, but as an image of self-absorbed beauty."[11] According to Wallace, "There is nothing spiritual about face or picture. The classical setting is an excuse for a very material aesthetic sexuality—not sex, as such, but an appreciation of the beauty that accompanies attraction."[12]

Intertwining pink silk ribbons are draped over the mirror and curl over its frame. The ribbon's function has been the subject of much debate by art historians; suggestions include an allusion to the fetters used by Cupid to bind lovers, that it was used to hang the mirror, and that it was used to blindfold Venus moments before.[7] The critic Julián Gallego found Cupid's facial expression to be so melancholy that he interprets the ribbons as fetters binding the god to the image of Beauty, and gave the painting the title "Amor conquered by Beauty".[13]

The folds of the bed sheets echo the goddess's physical form, and are rendered to emphasise the sweeping curves of her body.[5] The composition mainly uses shades of red, white, and grey, which are used even in Venus's skin; although the effect of this simple colour scheme has been much praised, recent technical analysis has shown that the grey sheet was originally a "deep mauve", that has now faded.[14] The luminescent colours used in Venus's skin, applied with "smooth, creamy, blended handling",[15] contrast with the dark greys and black of the silk she is lying on, and with the brown of the wall behind her face.

The Rokeby Venus is the only surviving nude by Velázquez, but three others by the artist are recorded in 17th-century Spanish inventories. Two were mentioned in the Royal collection, but may have been lost in the 1734 fire that destroyed the main Royal Palace of Madrid. A further one was recorded in the collection of Domingo Guerra Coronel.[17] These records mention "a reclining Venus", Venus and Adonis, and a Psyche and Cupid.[18]

Although the work is widely thought to have been painted from life, the identity of the model is subject to much speculation. In contemporary Spain it was acceptable for artists to employ male nude models for studies; however, the use of female nude models was frowned upon.[19] The painting is believed to have been executed during one of Velázquez's visits to Rome, and Prater has observed that in Rome the artist "did indeed lead a life of considerable personal liberty that would have been consistent with the notion of using a live nude female model".[19] It has been claimed that the painting depicts a mistress Velázquez is known to have had while in Italy, who is supposed to have borne his child.[12] Others have claimed that the model is the same as in Coronation of the Virgin and Las Hilanderas, both in the Museo del Prado, and other works.[16]

The figures of both Venus and Cupid were significantly altered during the painting process, the result of the artist's corrections to the contours as initially painted.[20] Pentimenti can be seen in Venus's upraised arm, in the position of her left shoulder, and on her head. Infra-red reveals that she was originally shown more upright with her head turned to the left.[14] An area on the left of the painting, extending from Venus's left foot to the left leg and foot of Cupid, is apparently unfinished, but this feature is seen in many other works by Velázquez and was probably deliberate.[21] The painting was given a major cleaning and restoration in 1965–66, which showed it to be in good condition, and with very little paint added later by other artists, contrary to what some earlier writers had asserted.[22]

Sources

Paintings of nudes and of Venus by Italian, and especially Venetian, artists were influences on Velázquez. However, Velázquez's version is, according to the art historian Andreas Prater, "a highly independent visual concept that has many precursors, but no direct model; scholars have sought them in vain".[23] Forerunners include Titian's various depictions of Venus, such as Venus and Cupid with a Partridge, Venus and Cupid with an Organist and notably the Venus of Urbino; Palma il Vecchio's Reclining Nude; and Giorgione's Sleeping Venus,[24] all of which show the deity reclining on luxurious textiles, although in landscape settings in the latter two works.[23] The use of a centrally placed mirror was inspired by the painters of the Italian High Renaissance, including Titian, Girolamo Savoldo and Lorenzo Lotto, who used mirrors as an active protagonist, as opposed to more than merely a prop or accessory in the pictorial space.[23] Both Titian and Peter Paul Rubens had already painted Venus looking into a mirror, and as both had had close ties to the Spanish court, their examples would have been familiar to Velázquez. However, "this girl with her small waist and jutting hip, does not resemble the fuller more rounded Italian nudes inspired by ancient sculpture".[25]

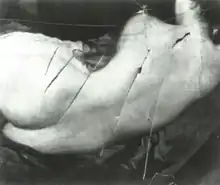

One innovation of the Rokeby Venus, when compared to other large single nude paintings, lies in the fact that Velázquez depicts a back view of its subject who is turned away from the viewer.[23] There were precedents for this in prints by Giulio Campagnola,[26] Agostino Veneziano, Hans Sebald Beham and Theodor de Bry,[27] as well as classical sculptures known to Velázquez, of which casts were made for Madrid. These were the Sleeping Ariadne now in the Pitti Palace, but then in Rome, of which Velázquez ordered a cast for the Royal collection in 1650–51, and the Borghese Hermaphroditus, a sleeping hermaphrodite (picture to the right above), now in the Louvre, of which a cast was sent to Madrid,[28] and which also emphasises the curve from hip to waist. However, the combination of elements in Velázquez's composition was original.

The Rokeby Venus may have been intended as a pendant to a sixteenth-century Venetian painting of a recumbent Venus (which seems to have begun life as a Danaë) in a landscape, in the same pose, but seen from the front. The two were certainly hung together for many years in Spain when in the collection of Gaspar Méndez de Haro, 7th Marquis of Carpio (1629–87); at what point they were initially paired is uncertain.[29]

Nudes in 17th-century Spain

The portrayal of nudes was officially discouraged in 17th-century Spain. Works could be seized or repainting demanded by the Inquisition, and artists who painted licentious or immoral works were often excommunicated, fined, or banished from Spain for a year.[30] However, within intellectual and aristocratic circles, the aims of art were believed to supersede questions of morality, and there were many, generally mythological, nudes in private collections.[5]

Velázquez's patron, the art-loving King Philip IV, held a number of nudes by Titian and Rubens, and Velázquez, as the king's painter, need not have feared painting such a picture.[14] Leading collectors, including the King, tended to keep nudes, many mythological, in relatively private rooms;[31] in Phillip's case "the room where His Majesty retires after eating", which contained the Titian poesies he had inherited from Phillip II, and the Rubens he had commissioned himself.[32] The Venus would be in such a room while in the collections of both Haro and Godoy. The court of Philip IV greatly "appreciated painting in general, and the nude in particular, but ... at the same time, exerted unparalleled pressure on artists to avoid the depiction of the naked human body."[18]

The contemporary Spanish attitude toward paintings of nudes was unique in Europe. Although such works were appreciated by some connoisseurs and intellectuals within Spain, they were generally treated with suspicion. Low necklines were commonly worn by women during the period, but according to the art historian Zahira Veliz, "the codes of pictorial decorum would not easily permit a known lady to be painted in this way".[33] For Spaniards of the 17th century, the issue of the nude in art was tied up with concepts of morality, power, and aesthetics. This attitude is reflected in the literature of the Spanish Golden Age, in works such as Lope de Vega's play La quinta de Florencia, which features an aristocrat who commits rape after viewing a scantily clad figure in a mythological painting by Michelangelo.[32]

In 1632,[35] an anonymous pamphlet—attributed to the Portuguese Francisco de Braganza—was published with the title "A copy of the opinions and censorship by the most revered fathers, masters and senior professors of the distinguished universities of Salamanca and Alcalá, and other scholars on the abuse of lascivious and indecent figures and paintings, which are mortal sin to be painted, carved and displayed where they can be seen".[36]

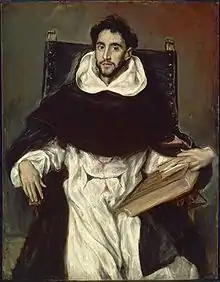

The court was able to exert counter-pressure, and a piece by the famous poet and preacher Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, which proposed the destruction of all paintings of the nude, and was written to be included in the pamphlet, was never published. Paravicino was a connoisseur of painting, and therefore believed in its power: "the finest paintings are the greatest threat: burn the best of them". As his title shows, Braganza merely argued that such works should be kept from the view of a wider public, as was in fact mostly the practice in Spain.[37]

In contrast, French art of the period often depicted women with low necklines and slender corsets;[39] however, the mutilation by the French royal family of the Correggio depiction of Leda and the Swan and their apparent destruction of the famous Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo paintings of the same subject, show that nudity could be controversial in France also.[40] In northern Europe it was seen as acceptable to portray artfully draped nudes. Examples include Rubens's Minerva Victrix, of 1622–25, which shows Marie de' Medici with an uncovered breast, and Anthony van Dyck's 1620 painting, The Duke and Duchess of Buckingham as Venus and Adonis.

In 17th-century Spanish art, even in the depiction of sibyls, nymphs, and goddesses, the female form was always chastely covered. No painting from the 1630s or 1640s, whether in the genre, portrait, or history format, shows a Spanish female with her breasts exposed; even uncovered arms were only rarely shown.[33] In 1997, the art historian Peter Cherry suggested that Velázquez sought to overcome the contemporary requirement for modesty by portraying Venus from the back.[41] Even in the mid-18th century, an English artist who made a drawing of the Venus when it was in the collection of the Dukes of Alba noted it was "not hung up, owing to the subject".[42]

Another attitude to the issue was shown by Morritt, who wrote to Sir Walter Scott of his "fine painting of Venus' backside", which he hung above his main fireplace, so that "the ladies may avert their downcast eyes without difficulty and connoisseurs steal a glance without drawing the said posterior into the company".[43]

Provenance

The Rokeby Venus was long held to be one of Velázquez's final works.[44] In 1951, it was found recorded in an inventory of 1 June 1651 from the collection of Gaspar Méndez de Haro, 7th Marquis of Carpio,[45] a close associate of Philip IV of Spain. Haro was the great-nephew of Velázquez's first patron, the Count-Duke of Olivares, and a notorious libertine. According to the art historian Dawson Carr, Haro "loved paintings almost as much as he loved women",[14] and "even his panegyrists lamented his excessive taste for lower-class women during his youth". For these reasons it seemed likely that he would have commissioned the painting.[46] However, in 2001 the art historian Ángel Aterido discovered that the painting had first belonged to the Madrid art dealer and painter Domingo Guerra Coronel, and was sold to Haro in 1652 following Coronel's death the previous year.[47] Coronel's ownership of the painting raises a number of questions: how and when it came into Coronel's possession, and why Velázquez's name was omitted from Coronel's inventory. The art critic Javier Portús has suggested that the omission may have been due to the painting's portrayal of a female nude, "a type of work which was carefully supervised and whose dissemination was considered problematic".[48]

These revelations make the painting difficult to date. Velázquez's painting technique offers no assistance, although its strong emphasis on colour and tone suggest that the work dates from his mature period. The best estimates of its origin put its completion in the late 1640s or early 1650s, either in Spain or during Velázquez's last visit to Italy.[14] If this is the case, then the breadth of handling and the dissolution of form can be seen to mark the beginning of the artist's final period. The conscientious modelling and strong tonal contrasts of his earlier work are here replaced by a restraint and subtlety which would culminate in his late masterpiece, Las Meninas.[49]

The painting passed from Haro into the collection of his daughter Catalina de Haro y Guzmán, the eighth Marchioness of Carpio, and her husband, Francisco Álvarez de Toledo, the tenth Duke of Alba.[50] In 1802, Charles IV of Spain ordered the family to sell the painting (with other works) to Manuel de Godoy, his favourite and chief minister.[51] He hung it alongside two masterpieces by Francisco Goya that he may have commissioned himself, The Nude Maja and The Clothed Maja. These bear obvious compositional similarities with Velázquez's Venus, although unlike Velázquez, Goya clearly painted his nude in a calculated attempt to provoke shame and disgust in the relatively unenlightened climate of 18th-century Spain.[52] The painting disappeared from the Godoy palace during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, and passed through the hands of George Augustus Wallis, a British painter, who worked in Spain as an agent for William Buchanan, a major art dealer, who brought it to England in 1813.[53][54]

In October 1813 Buchanan had offered shares in a package of twenty-four top paintings from Spanish collections to wealthy English collectors, who would be able to either buy them themselves, or share in the profits from sales to others in London. The Venus was one of them.[55] This arrangement was similar to that by which the cream of the Orleans Collection had been brought to London some years earlier.

In England it was purchased by John Morritt[56] for £500 (£ 35,000 in 2023), and on the advice of his friend Sir Thomas Lawrence. Morritt hung it in his house at Rokeby Park, Yorkshire—thus the painting's popular name. In 1906, the painting was acquired for the National Gallery by the newly created National Art Collections Fund, its first campaigning triumph.[57] King Edward VII greatly admired the painting, and anonymously provided £8,000 (£ 920,000 in 2023) towards its purchase,[58] and became Patron of the Fund thereafter.[59]

Legacy

In part because he was overlooked until the mid-19th century, Velázquez found no followers and was not widely imitated. In particular, his visual and structural innovations in this portrayal of Venus were not developed by other artists until recently, largely owing to the censorship of the work.[60] The painting remained in a series of private rooms in private collections until it was exhibited in 1857 at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, along with 25 other paintings at least claimed to be by Velázquez; it was here that it became known as the Rokeby Venus. It does not appear to have been copied by other artists, engraved or otherwise reproduced, until this period. In 1890 it was exhibited in the Royal Academy in London, and in 1905 at Messrs. Agnews, the dealers who had bought it from Morritt. From 1906 it was highly visible in the National Gallery and became well-known globally through reproductions. The general influence of the painting was therefore long delayed, although individual artists would have been able to see it on occasion throughout its history.[61]

The painting was not universally accepted as Velázquez's work on its reintroduction to the public. The artist William Blake Richmond, in a lecture at the Royal Academy in 1910 claimed that "two pigments used in the picture did not exist in the time of Velasquez." The critic, James Grieg hypothesised that it was by Anton Raphael Mengs—although he found little support for his idea—and there was more serious discussion about the possibility of Velázquez's son-in-law and pupil, Juan del Mazo as the artist.[62]

Velázquez's portrait is a staging of a private moment of intimacy and a dramatic departure from the classical depictions of sleep and intimacy found in works from antiquity and Venetian art that portray Venus. However, the simplicity with which Velázquez displays the female nude—without jewellery or any of the goddess's usual accessories—was echoed in later nude studies by Ingres, Manet, and Baudry, among others.[60] In addition, Velázquez's depiction of Venus as a reclining nude viewed from the rear was a rarity before that time, although the pose has been painted by many later artists.[63] Manet, in his stark female portrayal Olympia, paraphrased the Rokeby Venus in pose and by suggesting the persona of a real woman rather than an ethereal goddess. Olympia shocked the Parisian art world when it was first exhibited in 1863.[64]

Vandalism, 1914

On 10 March 1914, the suffragette Mary Richardson walked into the National Gallery and attacked Velázquez's canvas with a meat cleaver. Her action was ostensibly provoked by the arrest of fellow suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst the previous day,[66] although there had been earlier warnings of a planned suffragette attack on the collection. Richardson left seven slashes on the painting, particularly causing damage to the area between the figure's shoulders.[17][67] However, all were successfully repaired by the National Gallery's chief restorer Helmut Ruhemann.[12]

Richardson was sentenced to six months' imprisonment, the maximum allowed for destruction of an artwork.[68] In a statement to the Women's Social and Political Union shortly afterwards, Richardson explained, "I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history."[67][69] She added in a 1952 interview that she did not like "the way men visitors gaped at it all day long".[70]

The feminist writer Lynda Nead observed, "The incident has come to symbolize a particular perception of feminist attitudes towards the female nude; in a sense, it has come to represent a specific stereotypical image of feminism more generally."[71] Contemporary reports of the incident reveal that the picture was not widely seen as mere artwork. Journalists tended to assess the attack in terms of a murder (Richardson was nicknamed "Slasher Mary"), and used words that conjured wounds inflicted on an actual female body, rather than on a pictorial representation of a female body.[68] The Times described a "cruel wound in the neck", as well as incisions to the shoulders and back.[72]

See also

Notes

- According to two seventeenth-century accounts noted in Haskell and Penny 1981, p. 234.

- According to Clark, the Rokeby Venus "ultimately derives from the Borghese Hermaphrodite". Clark, p. 373, note to page 3.

- "The Rokeby Venus". National Gallery, London. Retrieved on 25 December 2007.

- This discrepancy has been termed the "Venus effect" by researchers of the University of Liverpool, who argue that "since the viewer sees her face in the mirror, Venus is actually looking at the reflection of the viewer". Nonetheless, despite that her face is indeed turned as if looking at the viewer's reflection, weak but noticeable corneal reflections painted on her eyes indicate a direction of gaze not towards the viewers but rather away from them. It is as if Venus were gazing in the direction of what would have been her own reflection on the mirror were the discrepancy not to exist (her corneal reflections can be seen with the magnification tool on the right of the painting's image here). With her eyes to the right, the scene's illumination, which comes exclusively from the top left, could not produce such reflections on her corneas; it seems parsimonious that Velázquez—a master painter most unlikely to have erred on where to place reflections—created on purpose a scene that could not exist. Given this conflicting duality, it is noteworthy the main webpage of the National Gallery about the Rokeby Venus describes her as looking "both at herself and at the viewer" (even though she is described as "returning our gaze" in another Gallery webpage, Focus painting for February 2010 Archived 4 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 27 September 2010).

- Carr, p. 214.

- MacLaren, p. 126. and Carr, p. 214.

- Prater, p. 40.

- Prater, p. 51.

- Carr, p. 214. It does not, however, seem clear to Wallace, quoted below.

- Gregory, R. L., Mirrors in mind (London: Penguin, 1997, ISBN 0-14-017118-5). He notes that "the image is with legitimate artistic licence at least twice the size it should be" (p. 21). The enlarged size presumably was the correction for the small image yielded by a mirror behind the subject.

- Wallace, Natasha. "Venus at her Mirror". JSS Virtual Gallery, 17 November 2000. Retrieved on 4 January 2008.

- Davies, Christie. "Velazquez in London". New Criterion, Volume: 25, Issue: 5, January 2007.

- Gallego, Julián. "Vision et symboles dans la peinture espagnole du siecle d'or". Paris: Klincksieck, 1968. p. 59f.

- Carr, p. 217

- Keith, Larry; in Carr, p. 83.

- Noting the resemblance of the model in these paintings, López-Rey offered: "Obviously, Velázquez worked in both cases, and, for that matter, in the Fable of Arachne and Arachne, from the same model, the same sketch, or just the same idea of a beautiful young woman. Yet, he put on canvas two different images, one of divine and the other of earthly beauty". López-Rey, vol. I, p. 156. However, MacLaren (p. 127) does not endorse these suggestions; they would probably argue that the painting was not produced in Italy. The Prado "Coronation" is dated to 1641–42; the present image is "stretched" vertically compared with the original.

- MacLaren, p. 125.

- Portús, p. 56.

- Prater, pp. 56–57.

- López-Rey believed that an overzealous cleaning in 1965 unevenly exposed some of Velázquez's "tentative contours", resulting in a loss of subtlety and contravening the artist's intent. López-Rey, vol II, p. 260. However, the National Gallery catalogue retaliates by describing López-Rey's description of the painting's condition as "largely misleading". MacLaren, p. 127.

- Carr, p. 217, see also MacLaren, p. 125 for the opposite view.

- MacLaren, p. 125. In particular, it had been claimed that the face in the mirror had been overpainted. See note above for López-Rey's criticism of the cleaning.

- Prater, p. 20.

- The landscape probably done or finished by Titian, after Giorgione's death

- Langmuir, p. 253

- Campagnola, Giulio: Liegende Frau in einer Landschaft. Zeno.org. Retrieved on 14 March 2008.

- Portús, p. 67, note: 42; citing Sánchez Cantón.

- MacLaren, p. 126

- Portús, p. 66, illus. fig. 48. According to Portús, what is almost certainly the other painting was lost trace of after a sale in 1925, but "recently rediscovered in a private collection in Europe" according to Langmuir, p. 253, who says the two are recorded in the same room in one of Haro's palaces by 1677. The rediscovery was made, and the painting identified, by Alex Wengraf in 1994 according to Harris and Bull in Harris Estudios completos sobre Velázquez: Complete Studies On Velázquez pp. 287–89. An attribution to Tintoretto has been suggested.

- Hagen II, p. 405.

- See Cabinet (room); such paintings were known as "cabinet pictures".

- Portús, pp. 62–63.

- Veliz, Zahira. "Signs of Identity in Lady with a Fan by Diego Velázquez: Costume and Likeness Reconsidered". Art Bulletin, Volume: 86. Issue: 1. 2004

- Javier Portús, p. 63, in: Carr, Dawson W. Velázquez. Ed. Dawson W. Carr; also Xavier Bray, Javier Portús and others. National Gallery London, 2006. ISBN 1-85709-303-8

- Portús p. 63 claims the year 1673, but this appears to be an error. The chapter "Nudes" in Spanish Painting From El Greco to Picasso (PDF), Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior (SEACEX), Retrieved on 16 March 2008, which refers to his research and also covers this topic, says 1632, and mentions references to the work by various other writers before 1673, including Francisco Pacheco, died 1644, in his Arte de Pintura.

- Serraller, pp. 237–60.

- Portús, pp. 63.

- Prater, p. 41.

- The engravings of such artists as Wenceslaus Hollar and Jacques Callot show, according to Veliz, "an almost documentary interest in the form and detail of European costume in the second quarter of the seventeenth century".

- Bull, Malcolm. "The Mirror of the Gods, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods". Oxford UP, 2005. p. 169. ISBN 0-19-521923-6

- Cherry, Peter. "Seventeenth-Century Spanish Taste2. Collections of Paintings in Madrid 1601–1755, vol. 2. CA: Paul Getty Information Inst. 1997. p. 73f.

- MacLaren, pp. 128–9.

- Bray; in Carr, p. 99.

- López-Rey noted that based on stylistic qualities, Beruete (Aureliano de Beruete, Velázquez, Paris, 1898) assigned the painting to the late 1650s. López-Rey, vol. I, p. 155.

- From 1648; before that Marquis of Heliche, by which title he is sometimes referred to. Portús, p. 57.

- Fernandez, Angel Aterido. "The First Owner of the Rokeby Venus". The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 143, No. 1175, February, 2001. pp. 91–94.

- Aterido, pp. 91–92.

- Portús, p. 57.

- Gudiol, p. 261.

- López-Rey, vol. II, p. 262.

- MacLaren, p. 126.

- Schwarz, Michael. "The Age of the Rococo". London: Pall Mall Press, 1971. p. 94. ISBN 0-269-02564-2

- Buchanan, William (1824). Memoirs of painting. Strand, London: R. Ackermann.

- Bray, in Carr, p. 99; MacLaren, p. 127

- Glendinning, 67

- Bray, in Carr, p. 99; MacLaren, p. 127.

- Covered in detail by: Pezzini, Barbara, “Days with Velázquez: When Charles Lewis Hind Bought the ‘Rokeby Venus’ for Lockett Agnew”, The Burlington Magazine 158, no. 1358 (2016), pp 358–67, JSTOR

- Bray; in Carr, p. 107

- Smith, Charles Saumarez. "The Battle for Venus: In 1906, the King Intervened to Save a Velazquez Masterpiece for the Nation. If Only Buckingham Palace, or Indeed Downing Street, Would Now Do the Same for Raphael's Madonna of the Pinks". New Statesman, Volume 132, Issue 4663, 10 November 2003. p. 38.

- Prater, p. 114.

- Carr, p. 103, and MacLaren, p. 127, the latter of whom would mention copies and early prints if there were any.

- MacLaren p. 76 dismisses both claims: "The supposed signatures of Juan Bautista Mazo and Anton Raphael Mengs in the bottom left corner are purely accidental marks."

- "The more frequent appearance of the motif in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries is probably owing to the prestige of the antique figure of Hermaphrodite....In Renaissance art the earliest example of a nude woman lying with her back to the spectator is the Giulio Campagnola engraving, which probably represents a design by Giorgione"....Clark, 391, note to page 150.

- "And when Manet painted his Olympia in 1863, and changed the course of modern art by provoking the mother of all art scandals with her, to whom was he paying homage? Manet’s Olympia is the Rokeby Venus brought up to date — a whore descended from a goddess." Waldemar Januszczak, Times Online (8 October 2006). Still sexy after all these years. Retrieved on 14 March 2008.

- Potterton, Homan. The National Gallery. London: Thames and Hudson, 1977. 15

- Davies, Christie. "Velazquez in London". New Criterion. Volume: 25. Issue: 5, January 2007. p. 53.

- Prater, p. 7.

- Nead, Lynda. "The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality". New York: : Routledge, 1992. p. 2.

- Gamboni, p. 94-95.

- Whitford, Frank. "Still sexy after all these years". The Sunday Times, 8 October 2006. Retrieved on 12 March 2008.

- Nead, Lynda, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality, p. 35, 1992, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-02678-4

- "National Gallery Outrage. Suffragist Prisoner in Court. Extent of the Damage". The Times, 11 March 1914. Retrieved on 13 March 2008.

Sources

- Bull, Duncan and Harris, Enriqueta. "The companion of Velázquez's Rokeby Venus and a source for Goya's Naked Maja". The Burlington Magazine, Volume CXXVIII, No. 1002, September 1986. (A version is reprinted in Harris, 2006 below)

- Carr, Dawson W. Velázquez. Ed. Dawson W. Carr; also Xavier Bray, Javier Portús and others. National Gallery London, 2006. ISBN 1-85709-303-8

- Clark, Kenneth. The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-691-01788-3

- Gamboni, Dario. The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. Reaktion Books, 1997. ISBN 978-1-86189-316-1

- Glendinning, Nigel, in Spanish Art in Britain and Ireland, 1750-1920: Studies in Reception in Memory of Enriqueta Harris Frankfort, 2010, Tamesis, Editors: Enriqueta Harris, Hilary Macartney, Nigel Glendinning, ISBN 9781855662230, google books

- Gudiol, José. The Complete Paintings of Velázquez. Greenwich House, 1983. ISBN 0-517-40500-8

- Hagen, Rose-Marie and Rainer. What Great Paintings Say, 2 vols. Taschen, 2005. ISBN 978-3-8228-4790-9

- Harris, Enriqueta. Estudios completos sobre Velázquez: Complete Studies On Velázquez, CEEH, 2006. ISBN 84-934643-2-5

- Haskell, Francis and Penny, Nicholas. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1600–1900. Yale University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-300-02913-6

- Langmuir, Erica. The National Gallery companion guide, revised edition. National Gallery, London, 1997. ISBN 1-85709-218-X

- López-Rey, José. Velázquez: Catalogue Raisonné. Taschen, Wildenstein Institute, 1999. ISBN 3-8228-6533-8

- MacLaren, Neil; revised Braham, Allan. The Spanish School, National Gallery Catalogues. National Gallery, London, 1970. pp. 125–9. ISBN 0-947645-46-2

- Portús, Javier. Nudes and Knights: A Context for Venus, in Carr

- Prater, Andreas. Venus at Her Mirror: Velázquez and the Art of Nude Painting. Prestel, 2002. ISBN 3-7913-2783-6

- White, Jon Manchip. Diego Velázquez: Painter and Courtier. Hamish Hamilton Ltd, 1969.

External links

- National Gallery: The Rokeby Venus

- Info from the Web Gallery of Art

- Biography of Mary Richardson

- Velázquez , exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Rokeby Venus (see index)