Royal Leicestershire Regiment

The Leicestershire Regiment (Royal Leicestershire Regiment after 1946) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, with a history going back to 1688. The regiment saw service for three centuries, in numerous wars and conflicts such as both World War I and World War II, before being amalgamated, in September 1964, with the 1st East Anglian Regiment (Royal Norfolk and Suffolk), the 2nd East Anglian Regiment (Duchess of Gloucester's Own Royal Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire) and the 3rd East Anglian Regiment (16th/44th Foot) to form the present day Royal Anglian Regiment, of which B Company of the 2nd Battalion continues the lineage of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment.

| 17th Regiment of Foot 17th (Leicestershire) Regiment of Foot Leicestershire Regiment Royal Leicestershire Regiment | |

|---|---|

Badge of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment | |

| Active | 1688–1964 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Line infantry |

| Garrison/HQ | Glen Parva Barracks |

| Nickname(s) | The Tigers |

History

Early wars

On 27 September 1688 a commission was issued to Colonel Solomon Richards to raise a regiment of foot in the London area.[1] In its early years, like other regiments, the regiment was known by the name of its various colonels. Following a failed attempt to break the siege of Derry in 1689, Richards was dismissed and replaced by the Irishman George St George.[2] The regiment embarked for Flanders in 1693 for service in the Nine Years' War[3] and took part in the attack of Fort Knokke in June 1695 and the siege of Namur in summer 1695[4] before returning home in 1697.[5]

In 1701 the regiment moved to Holland for service in the War of the Spanish Succession and fought at the siege of Kaiserswerth in 1702,[6]the siege of Venlo later that year[6] and the capture of Huy in 1703.[7] It transferred to Portugal in 1704[8] and took part in the sieges of Valencia de Alcántara, Alburquerque and Badajoz in 1705[9] as well as the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo in 1706.[10] It also saw action at the Battle of Almansa in April 1707[10] before returning to England in 1709.[11] In spring 1713, the regiment was ranked 17th in seniority.[12] It went to Scotland to suppress the Jacobite rising of 1715 and fought at the Battle of Sheriffmuir in November 1715.[11]

In 1726 the regiment moved to Menorca,[13] assisting the garrison at Gibraltar during its siege in 1727. The regiment remained on duty in the Balearic Islands until 1748,[13] where it moved to Ireland.[14]

On 1 July 1751 a royal warrant assigned numbers to the regiments of the line, and the unit became the 17th Regiment of Foot.[14]

The regiment embarked for Nova Scotia in 1757 for service in the French and Indian War;[14] it fought at the siege of Louisbourg in June 1758,[15] at the Battle of Toconderoga in July 1759.[16] The following year, the regiment took part in the successful three-pronged attack against Montréal in September.[17] It also saw engagements in the West Indies in 1762 and during Pontiac's Rebellion before assignment to Ireland in 1763 and then a return to England in 1767.[18]

By 1769, the regiment was back at full strength and declared "fit for service" at its annual inspection,[19] and was augmented in 1771 with 20 men added to each company, and the addition of a dedicated light company, ordered by the King on December 25, 1770.[lower-alpha 1]

American War of Independence

After the outbreak of hostilities at the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the regiment embarked for Boston from Ireland in the fall of 1776. Rough seas saw its companies separated: its first four companies landed in November, and the remaining six after Christmas 1776.[21] Along with the rest of the garrison, the regiment was evacuated after the Siege of Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia. At this time, Lieutenant-Colonel John Darby was superseded by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Mawhood, formerly Lieutenant-Colonel of the 19th Regiment of Foot, on April 4, 1776.[lower-alpha 2]The regiment set sail from Halifax with the army on June 29 for the invasion of New York, landing unopposed on Staten Island in July. It saw action at the Battle of Long Island in August 1776,[23] was part of the reserve at the Battle of White Plains in October 1776[24] and the Battle of Fort Washington in November 1776.[24]

Heroes of Princeton

The regiment also took part in the Battle of Princeton in January 1777. Not knowing that he was facing a superior force, Mawhood ordered an attack, Captain William Leslie was killed,[25][26] but the regiment routed a militia division, and killed rebel General Hugh Mercer. However, the rest of the rebel army was brought up and the regiment quickly found themselves surrounded. With superior rebel numbers, the regiment was forced to retreat. Mawhood ordered a desperate bayonet charge to break out of their encirclement, which succeeded. At the same time, Captain William Scott of the 17th Regiment, with just 40 men, successfully defended the 4th Brigade's baggage train against superior numbers of rebel attackers. Thomas Sullivan of the 49th Regiment of Foot remarked:[27]

"He formed his men upon commanding ground, and after refusing to deliver the Baggage, fought with his men back-to-back; and forced the Enemy to withdraw, bringing off the Baggage safe to Brunswick."

Performance in the battle was mentioned in dispatches,[lower-alpha 3] Later, the regiment was lauded as "The Heroes of Prince-town" in British recruiting adverts.[29]

It went on to fight at the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777,[30] the Battle of Germantown in October 1777,[30] and the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778. In September 1778, the regiment took part in Grey's raid at New Bedford and Martha's Vineyard, destroying rebel stores and making off with forage and plunder.[31]

Several companies and the regimental colours were captured[lower-alpha 4] at the Battle of Stony Point in July 1779[33][34] by a daring night-time bayonet charge by "Mad" Anthony Wayne.[35] The remaining companies of grenadiers and light infantry were detached to composite flank battalions, while the remaining men, drafts, and recruits from England were formed into the "17th Company" under Captain-Lieutenant George Cuppaidge, who was on business in New York during the action at Stony point. The 17th Company was tasked with fighting partisans in South Carolina in 1780.[lower-alpha 5]

The reformed regiment was in action again at the Battle of Guilford Court House in March 1781 and surrendered with the rest of Cornwallis's army at the siege of Yorktown in September 1781.[36]

The 17th Company, still in South Carolina during the events of Yorktown, fought in the last major action of the war at the Battle of the Combahee River, where the famous rebel Colonel John Laurens lost his life.[37]

The Leicestershire Regiment

A royal warrant dated 31 August 1782 bestowed county titles on all regiments of foot that did not already have a special designation "to cultivate a connection with the County which might at all times be useful towards recruiting". The regiment became the 17th (Leicestershire) Regiment of Foot.[36] The regiment was withdrawn from New York at the end of the war to Nova Scotia in 1783 before returning to England in 1786.[36]

The regiment was increased to two battalions in 1799 and both battalions took part in the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland, being present at the Battle of Bergen in September 1799[38] and the Battle of Alkmaar in October 1799,[39] before the second was disbanded in 1802.[39] In 1804 the regiment moved to India,[39] and remained there until 1823.[40] In 1825 the regiment was granted the badge of a "royal tiger" to recall their long service in the sub-continent.[lower-alpha 6] During this time, the regiment fought in the Gurkha War (1814-16) and the Third Maratha War (1817-18).[41] The Regiment was posted to New South Wales from 1830 to 1836.[42]

Australian frontier wars

During the early years of the Moreton Bay penal colony, in the area of Australia now known as South East Queensland, the 17th Regiment was involved in two documented incidents of Aboriginal massacre.[43]

The first was on Moreton Island, traditional home of the Ngugi people. On 1 July 1831, the then Commandant of the colony, Captain Clunie with a detachment of the 17th Regiment surrounded a Ngugi camp at dawn on the edge of the freshwater lagoon close to the island's southern extremity, killing up to twenty of them. George Watkins recorded: ‘nearly all were shot down. My informant, a young boy at the time, escaped with a few others by hiding in a clump of bushes’[44][43]

The second documented massacre was the following year in late December 1832, on the neighbouring island of Minjerribah. Six members of the local Nunukul tribe were killed at the hands of Captain Clunie and the 17th Regiment in a reprisal attack for the alleged Aboriginal attack on a ship.[45][46][43]

In the mid 1830s, the Gringai people who lived in the valleys and hills to the north of Newcastle, were at war with the European colonists. In 1835, in response to the murder of two shepherds, New South Wales governor Sir Richard Bourke ordered 50 soldiers from the 17th Regiment to proceed to the scene of the disturbance.[47] This military operation was commanded by Major William Croker,[48] and his directive from Bourke was to vigorously suppress the resistance. Croker's men returned after a month in the disputed area.[49]

The Victorian era

The regiment returned to India in 1837, and then took part in the Battle of Ghazni in July 1839 and the Battle of Khelat in November 1839 during the First Anglo-Afghan War.[50] The regiment next came under fire at the siege of Sevastopol in winter 1854 during the Crimean War.[51] In 1858 a second battalion was raised.[51]

- See main article Leicester Town Rifles

An invasion scare in 1859 led to the emergence of the Volunteer movement, and within a year there were 10 Rifle Volunteer Corps in Leicestershire, with titles like the 'Leicester Town Rifles' and the 'Duke of Rutland's Belvoir Rifles'. Together these formed an administrative battalion, which became the 1st Volunteer Battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment in 1880. By 1900, when the unit provided a detachment of volunteers to serve alongside the Regulars during the Second Boer War, it operated as a double-battalion unit.[52][53][54][55][56]

Childers reforms

The regiment was not fundamentally affected by the Cardwell Reforms of the 1870s, which gave it a depot at Glen Parva Barracks from 1873, or by the Childers reforms of 1881 – as it already possessed two battalions, there was no need for it to amalgamate with another regiment.[57] Under the reforms the regiment became The Leicestershire Regiment on 1 July 1881.[58]

The regiment also incorporated the local militia and rifle volunteers and consisted of:

- The 1st and 2nd Battalions (formerly the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 17th Foot)

- 3rd (Militia) Battalion (formerly the Leicestershire Militia)

- 1st Leicestershire Rifle Volunteer Corps, redesignated as the 1st Volunteer Battalion in 1883.[59][54]

The 1887 execution of a Leicestershire Regiment private for murdering a sergeant in India may have inspired Rudyard Kipling to write his poem "Danny Deever".[60]

The 1st and 3rd battalions fought in the Second Boer War 1899 – 1902, and the 1st Volunteer Battalion provided a detachment of volunteers to serve alongside the Regulars. The 2nd Battalion was stationed as a garrison regiment in Ireland from 1896, and in Egypt from February 1900.[56][61]

Following the end of the war in South Africa, the 1st battalion was in late 1902 transferred to Fort St. George in Madras Presidency,[62] 540 officers and men leaving Port Natal on the SS Ortona arriving in Madras in late November.[63] The 2nd battalion was stationed at Guernsey at the same time.[64]

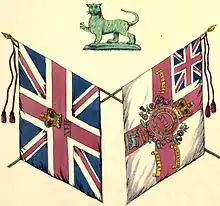

In 1908, the Volunteers and Militia were reorganised nationally, with the former becoming the Territorial Force and the latter the Special Reserve.[65] The 1st Volunteer Battalion was split to form the 4th and 5th Battalions (TF).[59][54][66] There was a minor controversy in the same year, when new colours were issued to the 1st Battalion to replace those of the 17th foot. A green tiger had been shown on the old colours and the regiment refused to take the new issue into use. The issue was resolved when the regiment received permission for the royal tiger emblazoned on the regimental colours to be coloured green with gold stripes.[67] The regiment now had one Reserve and two Territorial battalions.[68][69]

The First World War

In the First World War, the regiment increased from five to nineteen battalions which served in France and Flanders, Mesopotamia and Palestine.[70]

Regular Army

The 1st Battalion landed at Saint-Nazaire as part of the 16th Infantry Brigade in the 6th Division in September 1914 for service on the Western Front.[70] The Battalion saw action at the Battle of Hooge in July 1915 capturing a number of enemy trenches.[71] It then suffered terrible losses at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916.[71]

.jpg.webp)

_tank_of_'H'_Battalion%252C_'Hyacinth'%252C_ditched_in_a_German_trench_while_supporting_1st_Battalion%252C_Leicestershire_Regiment_near_Ribecourt_during_the_Battle_of_Cambrai%252C_20_November_1917._Q6432.jpg.webp)

The 2nd Battalion, commanded by Charles Blackader, landed at Marseille as part of the Garhwal Brigade in the 7th (Meerut) Division in September 1914 also for service on the Western Front.[70] The Battalion saw action at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915[71] when Private William Buckingham was awarded the Victoria Cross.[72] It then moved to Basra in Mesopotamia in December 1915[70] and took part in the action of Shaikh Saad in January 1916, the siege of Kut in Spring 1916, the capture of Sannaiyat in February 1917 and the fall of Baghdad in March 1917.[71] The battalion moved to Suez in January 1918 for service in the Palestine Campaign.[70]

Territorial Force

The 1/4th Battalion and 1/5th Battalion landed at Le Havre as part of the Lincoln and Leicester Brigade in the North Midland Division in March 1915 and February 1915 respectively for service on the Western Front.[70] The battalions saw action at the action of the Hohenzollern Redoubt in October 1915.[71] Lieutenant John Barrett was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions while serving with the 1/5th Battalion at Pontruet in September 1918 in the closing stages of the war.[73]

The 2/4th Battalion and 2/5th Battalion landed in France as part of the 2nd Lincoln and Leicester Brigade in the 2nd North Midland Division in February 1917 also for service on the Western Front.[70]

New Army battalions

The 6th (Service) Battalion, 7th (Service) Battalion, 8th (Service) Battalion and 9th (Service) Battalion landed in France as part of the 110th Brigade in the 37th Division in July 1915 for service on the Western Front.[70] The battalions took part in the attacks on High Wood at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916.[74] Lieutenant Colonel Philip Bent was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions while in command of the 9th (Service) Battalion at the Battle of Polygon Wood in September 1917.[75]

The 11th (Service) Battalion (Midland Pioneers) landed in France as the pioneer battalion for the 6th Division in March 1916 also for service on the Western Front.[70] Meanwhile, the 14th (Service) Battalion landed in France as part of the 47th Brigade in the 16th Division in July 1918 also for service on the Western Front.[70]

Inter-war

The regiment reverted to its pre-war establishment in 1919. The 1st Battalion was involved in the Irish War of Independence from 1920 to 1922, before moving to various overseas garrisons including Cyprus, Egypt and India. The 2nd Battalion was in India, Sudan, Germany and Palestine.[76]

In 1931 the regimental facing colour was changed from white to pearl grey. Previous to 1881 the 17th foot had "greyish white" facings.[67]

The 3rd (Militia) Battalion was placed in "suspended animation" in 1921, eventually being formally disbanded in 1953. In 1936 the 4th Battalion was converted into a searchlight unit as 44th (The Leicestershire Regiment) Anti-Aircraft Battalion of the Royal Engineers.[54] The size of the Territorial Army was doubled in 1939, and consequently the 1/5th and 2/5th Battalions were formed from the existing 5th.[74]

Regular Army battalions

The 1st Battalion was a Regular Army unit stationed in the Far East on the outbreak of the Second World War. The battalion fought the Imperial Japanese Army in the Malayan Campaign in early 1942 and sustained heavy casualties, temporarily amalgamating with the 2nd Battalion, East Surrey Regiment to create the British Battalion which was, however, later captured and the men of both battalions remained as prisoners of war (POWs) for the rest of the war.[77] The battalion reformed in May 1942 by the redesignation of the 8th Battalion.[78]

The 2nd Battalion, as part of the 16th Infantry Brigade, saw action at the Battle of Sidi Barrani in December 1940 and at the Battle of Bardia in January 1941 during the Western Desert Campaign.[74] The battalion then moved to Greece and took part in the Battle of Crete in May 1941 before transferring back to North Africa for the Battle of Tobruk in June 1941.[74] It then went to Ceylon in February 1942 and to India in January 1943: it became part of the Chindits and then saw action in the Burma Campaign.[74]

Territorial Army battalions

The 1/5th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, initially commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Barrett, who had won the VC while serving with the regiment during the Great War, was part of the 148th Infantry Brigade of the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division. The battalion fought briefly in the disastrous Norwegian Campaign before being withdrawn to the United Kingdom and then to Northern Ireland.[79] The battalion remained there for the rest of the war and saw no further active service.[74]

The 2/5th Battalion, created in 1939 as a duplicate of the 1/5th Battalion, and containing many formers of that battalion, was part of the 138th Infantry Brigade of the 46th Infantry Division and was sent to France in April 1940.[74] The battalion fought in the Battle of France as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1940, taking part in the Dunkirk evacuation, before returning to England. The battalion, briefly commanded by Richard Gale, remained there for the next two-and-a-half years on home defence and anti-invasion duties, leaving for North Africa in early 1943, fighting in the Tunisian Campaign, including the Battle of Kasserine Pass, until the campaign ended in mid-May 1943.[74] After resting for the next three months the battalion's next action was in the Allied invasion of Italy, where, holding off against numerous German counterattacks, heavy casualties were sustained. After a brief rest the battalion breached the Volturno Line in October before taking part in the battles around the Winter Line, most notably the Battle of Monte Cassino.[74] The battalion was withdrawn from the Italian Front in March 1944, sent to the Middle East to rest and retrain and absorb replacements after nearly six months of continuous action.[74] Returning to Italy in July, the battalion fought on the Gothic Line until December when the 2/5th, now commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Cubbon, was transported by air to Athens, Greece, to help calm the Greek Civil War, later returning to Italy in April 1945 but too late for participation in the final offensive. The end of World War II in Europe came soon afterwards and the battalion moved into Austria, where it was disbanded in 1946.[74]

The 44th AA Battalion transferred to the Royal Artillery in 1940, becoming 44th (The Leicestershire Regiment) Searchlight Regiment, in which role it served through the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. In 1942 it changed role again, becoming 121st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, which served in North West Europe from Operation Overlord to Germany.[54][80][81][82]

War Service battalions

The 7th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment was created in July 1940 in Nottingham in the aftermath of Dunkirk, when the BEF had been evacuated from France and a German invasion of England seemed likely. As a result, the British Army underwent a dramatic increase in size, mainly in the infantry, with the formation of numerous war service battalions, similar to the Kitchener battalions created in the Great War. The 7th Leicesters, composed largely of conscripts, and originally unbrigaded, was, in October 1940, assigned to the 205th Independent Infantry Brigade (Home).[74] The battalion's original role was mainly beach defence and anti-invasion duties and, upon the conversion of the 205th Brigade into the 36th Army Tank Brigade in late November 1941, the battalion was transferred to the 204th Independent Infantry Brigade (Home). In September 1942 the 7th Leicesters was sent to India, where the 2nd Battalion already was.[74] The following year the battalion was selected to be part of the Chindits, one of the only two non-Regular units to be chosen.[74] The battalion subsequently participated in the second Chindit expedition, codenamed Operation Thursday, where, by April 1944, the battalion was engaged in harassing the Japanese's rear and disrupting their lines of communication, along with ambushing reinforcements.[74] Relieved from the frontline in late 1944, the battalion returned to India to reform at Bangalore. Due to the heavy losses sustained in Operation Thursday, however, the battalion was disbanded on 31 December 1944, the few remaining men being sent to the 2nd Battalion.[74]

The 8th Battalion was, like the 7th Battalion, created in July 1940 after the Dunkirk evacuation, composed largely of conscripts, and, in late October, was assigned to the 222nd Independent Infantry Brigade and shared much of the same early history of the 7th Leicesters, spending most of its existence committed to beach defence and anti-invasion duties.[74] On 27 May 1942 the battalion was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, after the destruction of the original 1st Battalion in Singapore in February.[74] In mid-December the battalion was transferred to the 162nd Independent Infantry Brigade. In July 1944 the battalion transferred to the 147th Infantry Brigade, part of the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, then fighting, and suffering heavy casualties, in the Normandy Campaign. The reformed 1st Battalion, replacing the disbanded 1/6th Duke of Wellington's Regiment in the 147th Brigade, remained with this formation until the end of the war.[74] The battalion's first major engagement was the Second Battle of the Odon.

Post-war

In 1946 the regiment was granted "royal" status, becoming the Royal Leicestershire Regiment.[83] In 1948, in common with all other infantry regiments, the 2nd Battalion was abolished. The 5th Battalion (TA) had been reformed in 1947.[66] In 1948 the regiment became part of the Forester Brigade, sharing a depot at Budbrooke Barracks in Warwickshire with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment and the Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment). Glen Parva was downgraded to regimental headquarters.[84]

The 1st Battalion served in the Korean War from 1951 to 1952. They subsequently moved to England (exercising the freedom of the City of Leicester in 1952), Germany, Sudan, where they operated with the Sudan Defence Force and departed on 16 August 1955,[85] Cyprus, Brunei and Aden.[86]

The Territorial units were reformed in 1947 as 579 (The Royal Leicestershire Regiment) Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA and 5th Battalion Royal Leicesters. In 1961 they merged to become the 4th/5th Battalion.[54][66][80][82][87]

In 1963 the Forester Brigade was dissolved, with the Royal Leicesters and Royal Lincolns moving to the East Anglian Brigade where they joined the 1st, 2nd and 3rd East Anglian Regiments.[88]

Amalgamation into the Royal Anglian Regiment

On 1 September 1964 the regiments of the East Anglian Brigade became The Royal Anglian Regiment.[89] The 1st Battalion, Royal Leicestershire Regiment became the 4th (Leicestershire) Battalion, The Royal Anglian Regiment. The battalion garrisoned Malta as part of Headquarters Malta and Libya from 1965.[90]

The "Leicestershire" subtitle was removed on 1 July 1968 and the battalion was disbanded in 1975. The Royal Leicestershire heritage was included in the new regiment's button design, which features the royal tiger within an unbroken wreath.[91]

When the Territorial Army was converted into the Territorial and Army Volunteer Reserve (TAVR) in 1967, 4/5th Battalion provided two elements:[92]

- 4th (Leicestershire) Company, 5th (Volunteer) Battalion, Royal Anglian Regiment in TAVR II (units with a NATO role)

- The Royal Leicestershire Regiment (Territorials) in TAVR III (home defence units). The TAVR regiment was later reduced to B (Royal Leicestershire) Company, 7th (Volunteer) Battalion in the Royal Anglians. In 1978, 4th Coy 5th Bn and B Coy 7th Bn were amalgamated to form HQ (The Royal Leicestershire) Company of 7th Bn Royal Anglians[66]

A further reduction in the TA in 1999 saw HQ Company merged with C (Northamptonshire Regiment) Company to form C (Leicestershire and Northamptonshire) Company of the East of England Regiment, which was redesignated 3rd Bn Royal Anglian regiment in 2006.[93] Under the 2020 plans for the Army Reserve, C Company at Leicester will absorb B (Lincolnshire) Company by the end of 2016.[94]

Regimental museum

The Royal Leicestershire Regiment Museum is part of Newarke Houses Museum in Leicester.[95]

Battle honours

The regiment was awarded the following battle honours:[96][97]

- Earlier Wars

- Namur, 1695, Louisburg, Martinique, 1762, Havannah, Ghuznee, 1839, Khelat, Afghanistan 1839, Sevastopol, Ali Masjid, Afghanistan 1878–79, Defence of Ladysmith, South Africa, 1899–1902

- First World War (Ten selected honours, shown in bold type, were borne on the colours.)

- Aisne, 1914, '18, La Bassee, 1914, Armentieres, 1914, Festubert 1914, '15, Neuve Chapelle, Aubers, Hooge, 1915, Somme, 1916, '18, Bazentin, Flers-Courcelette, Morval, Le Transloy, Ypres, 1917, Polygon Wood, Cambrai, 1917, '18, St Quentin, Lys, Bailleul, Kemmel, Scherpenberg, Albert, 1918, Bapaume, 1918, Hindenburg Line, Épehy, St Quentin Canal, Beaurevoir, Selle, Sambre, France and Flanders, 1914–18, Megiddo, Sharon, Damascus, Palestine, 1918, Tigris, 1916, Kut-el-Amara, 1917, Baghdad, Mesopotamia, 1915–18

- Second World War (Ten selected honours, shown in bold type, were borne on the colours.)

- Norway, 1940, Antwerp-Turnhout Canal, Scheldt, Zetten, North-West Europe, 1944–45, Jebel Mazar, Syria, 1941, Sidi Barrani, Tobruk, 1941, Montaigne Farm, North Africa, 1940–41, '43, Salerno, Calabritto, Gothic Line, Monte Gridolfo, Monte Colombo, Italy, 1943–45, Crete, Heraklion, Kampar, Malaya, 1941–42, Chindits, 1944

- Korean War:

- Maryang-San, Korea, 1951–52

Colonels

The colonels of the regiment were as follows:

- 1688-1689: Col Solomon Richards[98]

- 1689-1695: George St George[98]

- 1695: Col James Courthorpe[98]

- 1695: Lt-Col Sir Matthew Bridges[98]

- 1703-1707: Lt-Col Holcroft Blood[98]

- 1707-1722: Lt-Col James Wightman[98]

- 1722: Brig-Gen Thomas Ferrers[98]

- 1722-1742: Col James Tyrrell[98]

- 1742-1752: Col John Wynyard[98]

The 17th Regiment of Foot

- 1752-1757: Brig-Gen Edward Richbell[98]

- 1757-1759: Col John Forbes[98]

- 1759-1782: Brig-Gen Hon. Robert Monckton[98]

The 17th (Leicestershire) Regiment

- 1782-1792: Major-Gen George Morrison[98]

- 1792-1819: Major-Gen George Garth[98]

- 1819-1840: Lt-Gen Sir Josiah Champagné GCH[98]

- 1840-1842: Gen Sir Frederick Augustus Wetherall GCH[98]

- 1843–1854: Lt-Gen Sir Peregrine Maitland KCB[98]

- 1854–1860: Lt-Gen. Thomas James Wemyss, CB[69]

- 1860–1868: Gen. Sir Richard Airey, 1st Baron Airey, GCB[69]

- 1868–1871: Lt-Gen. John Grattan, CB[69]

- 1871–1879: Gen. William Raikes Faber, CB[69]

- 1879–1890: Gen. Richard Curzon-Howe, 3rd Earl Howe, GCVO, CB[69]

The Leicestershire Regiment

- 1890–1895: Lt-Gen. John Christopher Guise, VC, CB[69]

- 1895–1903: Gen. Sir John Ross, GCB[69]

- 1903–1905: Maj-Gen. George Tito Brice[69]

- 1905–1912: Maj-Gen. Archibald Hammond Utterson, CB[69]

- 1912–1916: Maj-Gen. William Dalrymple Tompson, CB[69]

- 1916–1953: Maj-Gen. Sir Edward Mabbott Woodward, KCMG, CB[69]

- 1943–1948: Gen. Sir Clive Gerard Liddell, KCB, CMG, CBE, DSO[69]

The Royal Leicestershire Regiment

- 1948–1954: Brig. Harold Senhouse Pinder, CBE, MC[69]

- 1954–1963: Lt-Gen. Sir Colin Bishop Callander, KCB, KBE, MC[69]

- 1963–1964: Maj-Gen. Douglas Anthony Kendrew, CB, CBE, DSO

Victoria Crosses

The following members of the Regiment were awarded the Victoria Cross:

- Lieutenant John Cridlan Barrett, First World War (24 September 1918)

- Lieutenant Colonel Philip Eric Bent, Belgium, First World War (1 October 1917)

- Private William Buckingham, First World War (10/12 March 1915)

- Corporal Philip Smith, Radan, Crimean War (18 June 1855)

See also

- John Sheppard – The first British soldier to destroy enemy tanks in the Second World War.

Notes

- WO 25/3997. National Archive. "20 private men were added to each Company, and a Company of Light Infantry of the same Numbers to each Battalion…amounting to 737, Including Officers & Contingent Men."[20]

- Howe's Orders, Boston, 4th Apr., 1776. “17th. Regiment.—Lieutenant-Colonel Mawhood, of the 19th. Regiment, to be Lieutenant-Colonel Vice Derby 26th. Oct., 1775.”[22]

- "HEAD QUARTERS, New York, Jan. 8th., 1777."[28]

- From MSS. Letter Book of Colonel Febiger: "We took 15 pieces of Artillery, with fixed ammunition for a three months' siege, 2 standards and 1 flag, 10 marquees and a large quantity of tents, Quartermaster's stores, baggage, &c., , Sc."[32]

- Documented in "A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781," North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 9, Jan-Oct 1932

- 24 June 1825: His Majesty has been pleased to approve of the 17th or Leicestershire Regiment of foot bearing on its colours and appointments the figure of the "Royal Tiger," with the word "Hindoostan" superscribed, as a lasting testimony of the exemplary conduct of the Corps during its period of service in India, in the year 1804 to 1823."No. 18149". The London Gazette. 25 June 1825. p. 1105.

References

- Cannon 1848, p. 1.

- Cannon 1848, p. 3.

- Cannon 1848, p. 4.

- Cannon 1848, p. 5.

- Cannon 1848, p. 7.

- Cannon 1848, p. 8.

- Cannon 1848, p. 9.

- Cannon 1848, p. 10.

- Cannon 1848, p. 11.

- Cannon 1848, p. 12.

- Cannon 1848, p. 15.

- "WO 26/14" (1712-1717). War Office: entry books of warrants, regulations and precedents. National Archive.

- Cannon 1848, p. 16.

- Cannon 1848, p. 17.

- Cannon 1848, p. 18.

- Cannon 1848, p. 19.

- Cannon 1848, p. 21.

- Cannon 1848, p. 22.

- "WO 27/15" (1769). Office of the Commander-in-Chief and War Office: Adjutant General and Army Council: Inspection Returns. National Archive. Review of the 17th Regiment of Foot at Chatham by Major General George Cary, 17 May 1769.

- Tatum III 2023.

- Kemble 1884, p. 61-62.

- Kemble 1884, p. 329.

- Cannon 1848, p. 23.

- Cannon 1848, p. 24.

- Cannon 1848, p. 25.

- "No. 11747". The London Gazette. 22 February 1777. p. 2.

- Sullivan 2019, p. 101.

- Kemble 1884, p. 434-435.

- Laffin 1966, p. 35.

- Cannon 1848, p. 26.

- André 1904, p. 58).

- Johnston 1900, p. 187.

- Cannon 1848, p. 27.

- "No. 12019". The London Gazette. 2 October 1779. pp. 1–2.

- "Stoney Point Battlefield". Revolutionary Day. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Cannon 1848, p. 28.

- Massey 2016, p. 228.

- Cannon 1848, p. 30.

- Cannon 1848, p. 31.

- Cannon 1848, p. 37.

- Cannon 1848, p. 34-36.

- Australia's Red Coat Regiments.

- "Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930". Centre For 21st Century Humanities. University of Newcastle. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Watkins 1892, p. 40-50.

- "Item ID11936, CSL micro 8 Cluny 12 Jan 1883". Queensland State Archives.

- Evans 1999, p. 65.

- "The Sydney Herald". The Sydney Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 11 June 1835. p. 2. Retrieved 9 April 2020 – via Trove.

- "ADVANCE AUSTRALIA Sydney Gazette". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 11 June 1835. p. 2. Retrieved 9 April 2020 – via Trove.

- "MATTER FURNISHED BY OUR Reporters and Correspondents". The Sydney Monitor. New South Wales, Australia. 15 July 1835. p. 3 (MORNING). Retrieved 9 April 2020 – via Trove.

- Cannon 1848, p. 41.

- "Part I Origin until 1914". Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Westlake 2010, p. 154-156.

- Beckett, Appendix VII.

- "4th Battalion, The Royal Leicestershire Regiment [UK]". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- MacDonald, p. 11.

- Leslie 1970.

- "Training Depots 1873–1881". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) The depot was the 27th Brigade Depot from 1873 to 1881, and the 17th Regimental District depot thereafter - "No. 24992". The London Gazette. 1 July 1881. pp. 3300–3301.

- Westlake 2010.

- Atwood 2015.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36058. London. 6 February 1900. p. 10.

- "Naval & Military intelligence - The Army in India". The Times. No. 36896. London. 11 October 1902. p. 12.

- "The Army in South Africa - Movement of Troops". The Times. No. 36925. London. 14 November 1902. p. 9.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36903. London. 20 October 1902. p. 8.

- "Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 31 March 1908. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "5th Battalion, The Royal Leicestershire Regiment [UK]". Archived from the original on 10 September 2006. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Military History Society Bulletin, Special Issue No.1, 1968

- These were the 3rd Battalion (Special Reserve), with the 4th Battalion at the Magazine in Leicester and the 5th Battalion at Granby Street in Loughborough (since demolished) (both Territorial Force).

- "The Leicestershire Regiment". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Baker, Chris. "The Leicestershire Regiment". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- "Part II The First World War". Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "No. 29146". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 April 1915. p. 4143.

- "No. 31067". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 December 1918. pp. 14774–14775.

- "Part IV The Second World War". Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "No. 30471". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 January 1918. pp. 722–723.

- "Part III Between the Wars". Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "British Battalion prisoner of war information". Children and Families of Far East Prisoners of War. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "A short history of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment: Part IV The Second World War 1939-1945". Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 325–6, 333.

- Litchfield, pp. 139–40.

- Routledge, pp 314, 319, 350, 360–5.

- Farndale, Annex M, pp. 338–9.

- Army Order 167/1946

- Whitaker's Almanack 1956, p. 471

- Palmer, Robert. "British Troops in the Sudan: History & Personnel" (PDF). www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- "Looking Back - Graham Eustace - Aden and Radfan". Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "British Army units from 1945 on". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Goldschmidt 2009.

- Swinson 1972, p. 270.

- "The Malta Scene" (PDF). Castle: The Journal of the Royal Anglian Regiment. 1 October 1967. p. 23. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Symbols and Badges". Royal Anglian Regiment Museum. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- "5th Battalion, The Royal Leicestershire Regiment [UK]". Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "The East of England Regiment [UK]". Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Army 2020 Reserve Structure and Basing Changes at British Army site.

- "Newarke Houses Museum". Ogilby Trust. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Battle Honours". The Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Royal Tigers' Association. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- Swinson 1972, pp. 105–106.

- Cannon, Richard. Historical record of the Seventeenth, or the Leicestershire Regiment of Foot: containing an account of the formation of the regiment in 1688, and of its subsequent services to 1848. Project Gutenberg.

Bibliography

- André, John (1904). Major André's Journal. Kindle Edition.

- Atwood, Rodney (15 January 2015). The Life of Field Marshal Lord Roberts. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-78093-629-1.

- Beckett, Ian F.W. (1982). Riflemen Form: A study of the Rifle Volunteer Movement 1859–1908. Aldershot: Ogilby Trusts. ISBN 0-85936-271-X.

- Cannon, Richard (1848). Historical record of the 17th or the Leicestershire Regiment of Foot: containing an account of the formation of the regiment in 1688 and of its subsequent services to 1848. Historical records of the British Army. Parker Furnivall & Parker.

- Evans, R (1999). The Mogwi take Mi-an-jin: race relations and the Moreton Bay penal settlement, 1824-1842. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0958782695.

- Farndale, Gen Sir Martin (1996). History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: The Years of Defeat: Europe and North Africa, 1939–1941. Brasseys. ISBN 1-85753-080-2.

- Goldschmidt, Michael (2009). Marching with the Tigers: The History of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment 1955-1975. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1848840355.

- Johnston, Henry P. (1900). The Storming of Stony Point on the Hudson, midnight, July 15, 1779; its importance in the light of unpublished documents. New York, J. T. White.

- Joslen, Lt-Col H.F. (2003). Orders of Battle, United Kingdom and Colonial Formations and Units in the Second World War, 1939–1945. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-843424-74-6.

- Kemble, Stephen (1884). Kemble Papers: Volume 1. Kemble's journals, 1773-1789 -- British Army orders : Gen. Sir William Howe, 1775-1778 ; Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, 1778 ; Gen. Daniel Jones, 1778. New York Historical Society.

- Laffin, John (1966). Tommy Atkins: The Story of the English Soldier. London: Cassell.

- Leslie, N.B. (1970). Battle Honours of the British and Indian Armies 1695–1914. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-004-5.

- MacDonald, Alan (2008). A Lack of Offensive Spirit? The 46th (North Midland) Division at Gommecourt, 1st July 1916. West Wickham: Iona Books. ISBN 978-0-9558119-0-6.

- Massey, Gregory D. (2016). John Laurens and the American Revolution. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-61117-613-1.

- Routledge, Brig N.W. (1994). History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: Anti-Aircraft Artillery 1914–55. Brassey's. ISBN 1-85753-099-3.

- Spurling, J.M.K. (1969). The Tigers – a short history of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment. Leicester.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sullivan, Thomas (2019). From Redcoat to Rebel: The Thomas Sullivan Journal. Heritage Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0788407444.

- Swinson, Arthur (1972). A Register of the Regiments and Corps of the British Army. London: The Archive Press. ISBN 0-85591-000-3.

- Tatum III, William P. (2023). "A Brief History of the 17th Regiment of Foot in America 1775-83". Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- Watkins, G (1892). "Notes on the Aborigines of Stradbroke and Moreton Islands". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland. 8 (2): 40–50. doi:10.5962/p.351167. S2CID 257092690.

- Webb, E. A. H. (1911). A History of the Service of the 17th (The Leicestershire) Regiment. London: Vacher and Sons Ltd. ISBN 9781843420811.

- Westlake, Ray (2010). Tracing the Rifle Volunteers. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978 1-84884-211-3.

- "Australia's Red Coat Regiments". Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

External links

- "The Royal Leicestershire Regiment". Royal Tigers' Association. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- Land Forces of Britain, the Empire and Commonwealth (Regiments.org)

- British Army units from 1945 on.

- Army 2020 Reserve Structure and Basing Changes at British Army site