Battle of La Bassée

The Battle of La Bassée was fought by German and Franco-British forces in northern France in October 1914, during reciprocal attempts by the contending armies to envelop the northern flank of their opponent, which has been called the Race to the Sea. The 6th Army took Lille before a British force could secure the town and the 4th Army attacked the exposed British flank further north at Ypres. The British were driven back and the German army occupied La Bassée and Neuve Chapelle. Around 15 October, the British recaptured Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée but failed to recover La Bassée.

| Battle of La Bassée | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Race to the Sea on the Western Front (First World War) | |||||||

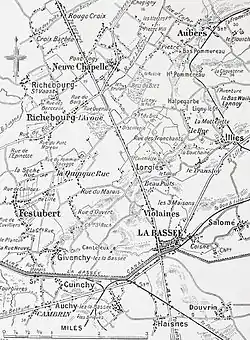

Neuve Chapelle to La Bassée area, 1914 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sir John French, Horace Smith-Dorrien James Willcocks Louis de Maud'huy Louis Conneau | Crown Prince Rupprecht | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

II Corps 2nd Cavalry Brigade Lahore Division French II Cavalry Corps (detachments) | 6th Army | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 15,000 | 6,000 | ||||||

La Bassée | |||||||

German reinforcements arrived and regained the initiative, until the arrival of the Lahore Division, part of the Indian Corps. The British repulsed German attacks until early November, after which both sides concentrated their resources on the First Battle of Ypres. The battle at La Bassée was reduced to local operations. In late January and early February 1915, German and British troops conducted raids and local attacks in the Affairs of Cuinchy, which took place at Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée and just south of La Bassée Canal, leaving the front line little changed.[lower-alpha 1]

Background

Strategic developments

From 17 September to 17 October the belligerents had tried to turn the northern flank of their opponent. Joffre ordered the French Second Army to move to the north of the French Sixth Army, by moving from eastern France from 2 to 9 September and Falkenhayn ordered the German 6th Army to move from the German-French border to the northern flank on 17 September. Next day, French attacks north of the Aisne led to Falkenhayn to order the 6th Army to repulse the French and secure the flank.[2] When the French advanced on 24 September, they met a German attack rather than an open flank and by 29 September, the Second Army had been reinforced to eight corps and extended north but was still opposed by German forces near Lille, rather than an open flank. The German 6th Army had also found that on arrival in the north, it was forced to oppose the French attack rather than advance around the flank and that the secondary objective of protecting the northern flank of the German armies in France, had become the main task.[3]

Tactical developments

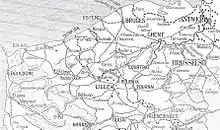

By 6 October, the French needed British reinforcements to withstand German attacks around Lille. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had begun to move from the Aisne to Flanders on 5 October and reinforcements from England assembled on the left flank of the Tenth Army, which had been formed from the left flank units of the Second Army on 4 October.[3] The Allies and the Germans attempted to take more ground, after the "open" northern flank had disappeared, Franco-British attacks towards Lille in October, being followed up by attempts to advance between the BEF and the Belgian army by a new French Eighth Army. The moves of the German 7th Army and then the 6th Army from Alsace and Lorraine, had been intended to secure German lines of communication through Belgium, where the Belgian army had sortied several times from the National redoubt of Belgium, during the period between the Franco-British retreat and the Battle of the Marne. In August British marines had landed at Dunkirk. In October a new German 4th Army was assembled from the III Reserve Corps, the siege artillery used against Antwerp and four of the new reserve corps training in Germany.[4]

Flanders terrain

The North-east of France and the south-west Belgium are known as Flanders. West of a line between Arras and Calais in the north-west, lie chalk downlands covered with soil sufficient for arable farming. To the east of the line, the land declines in a series of spurs into the Flanders plain, bounded by canals linking Douai, Béthune, Saint-Omer and Calais. To the south-east, canals run between Lens, Lille, Roubaix and Courtrai, the Lys river from Courtrai to Ghent and to the north-west lay the sea. The plain is almost flat, apart from a line of low hills from Cassel, east to Mont des Cats, Mont Noir, Mont Rouge, Scherpenberg and Mont Kemmel. From Kemmel, a low ridge lies to the north-east, declining in elevation past Ypres through Wytschaete, Gheluvelt and Passchendaele, curving north then north-west to Diksmuide where it merged with the plain. A coastal strip about 10 mi (16 km) wide was near sea level and fringed by sand dunes. Inland the ground was mainly meadow, cut by canals, dykes, drainage ditches and roads built up on causeways. The Lys, Yser and upper Scheldt had been canalised and between them the water level underground was close to the surface, rose further in the autumn and filled any dip, the sides of which then collapsed. The ground surface quickly turned to a consistency of cream cheese and on the coast troops were confined to roads, except during frosts.[5]

The rest of the Flanders Plain was woods and small fields, divided by hedgerows planted with trees and cultivated from small villages and farms. The terrain was difficult for infantry operations because of the lack of observation, impossible for mounted action because of the many obstructions and difficult for artillery because of the limited view. South of La Bassée Canal around Lens and Béthune was a coal-mining district full of slag heaps, pit heads (fosses) and miners' houses (corons). North of the canal, the city of Lille, Tourcoing and Roubaix formed a manufacturing complex, with outlying industries at Armentières, Comines, Halluin and Menin, along the Lys river, with isolated sugar beet and alcohol refineries and a steel works near Aire-sur-la-Lys. Intervening areas were agricultural, with wide roads on shallow foundations and unpaved mud tracks in France and narrow pavé roads, along the frontier and in Belgium. In France, the roads were closed by the local authorities during thaws to preserve the surface and marked by Barrières fermėes, which were ignored by British lorry drivers. The difficulty of movement after the end of summer absorbed much local labour on road maintenance, leaving field defences to be built by front-line soldiers.[6]

Prelude

Franco-British offensive preparations

By 4 October, the troops under Maud'huy were in danger of encirclement, German troops had reached Givenchy, north-west of Vimy and the French division on the northern flank was separated from the cavalry operating further north; a gap had also been forced between X Corps and the Territorial divisions to the south. Castelnau and Maud'huy wished to withdraw but rather than lose all of northern France, Joffre created a new Tenth Army, from Maud'huy's forces and gave Castelnau a directive, to maintain the Second Army in its positions, until the pressure of operations further north, diminished the power of German attacks between the Oise and the Somme. Foch was appointed deputy to Joffre and given command of all French troops in the north. On 6 October, the French line from the Oise to Arras was secured; Joffre and French had also agreed to concentrate the BEF around Doullens, Arras and St Pol, ready for operations on the left of the Tenth Army.[7]

By 8 October, the French XXI Corps had moved its left flank to Vermelles, just short of La Bassée Canal. Further north, the French I and II Cavalry corps (General Louis Conneau) and de Mitry, part of the 87th Territorial Division and some Chasseurs, held a line from Béthune to Estaires, Merville, Aire, Fôret de Clairmarais and St Omer, where the rest of the 87th Territorial Division connected with Dunkirk; Cassel and Lille further east were still occupied by French troops. Next day, the German XIV Corps arrived opposite the French, which released the German 1st and 2nd Cavalry corps to attempt a flanking move between La Bassée and Armentières. The French cavalry were able to stop the German attack north of the La Bassée–Aire canal. The 4th Cavalry Corps further north, managed to advance and on 7 October, passed through Ypres before being forced back to Bailleul, by French Territorial troops near Hazebrouck.[8] From 8 to 9 October, the British II Corps arrived by rail at Abbeville and was ordered to advance on Béthune.[9]

The British 1st and 2nd Cavalry divisions covered the arrival of the infantry and on 10 October, using motor buses supplied by the French, II Corps advanced 22 mi (35 km).[lower-alpha 2] By the end of 11 October, II Corps held a line from Béthune to Hinges and Chocques, with flanking units on the right 3.5 mi (5.6 km) south of Béthune and on the left 4.5 mi (7.2 km) to the west of the town.[12] On 12 October, the II Corps divisions attacked to reach a line from Givenchy to Pont du Hem, 6 mi (9.7 km) north of La Bassée Canal, across ground which was flat and dotted with farms and buildings as far as a low ridge 10 mi (16 km) east of Béthune. The German defenders of I and II Cavalry corps and attached Jäger disputed every tactical feature but the British advance continued and a German counter-attack near Givenchy was repulsed. The British dug in from Noyelles to Fosse. On 13 October, the II Corps attack by the 3rd Division and the French 7th Cavalry Division gained little ground and Givenchy was almost lost when the German attacked in a rainstorm, the British losing c. 1,000 casualties.[13]

German offensive preparations

The 6th Army had arrived in northern France and Flanders from the south and progressively relieved German cavalry divisions, VII Corps taking over from La Bassée to Armentières on 14 October, XIX Corps next day around Armentières and XIII Corps from Warneton to Menin. Attacks by the British II and III Corps caused such casualties that XIII Corps was transferred south from 18 to 19 October in reinforcement. The 6th Army line from La Bassée to Armentières and Menin, was ordered not to attack until the operations of the new 4th Army in Belgium had begun.[14] Both armies attacked on 20 October, the XIV, VII, XIII and XIX corps of the 6th Army making a general attack from Arras to Armentières. Next day the northern corps of the 6th Army attacked from La Bassée to St Yves and gained little ground but prevented British and French troops from being moved north to Ypres and the Yser fronts.[15] On 27 October, Falkenhayn ordered the 6th Army to move heavy artillery north for the maximum effort due on 29 October at Gheluvelt, to reduce its attacks on the southern flank against II and III corps and to cease offensive operations against the French further south.[16] Armeegruppe von Fabeck was formed from XIII Corps and reinforcements from the armies around Verdun, which further depleted the 6th Army and ended the offensive from La Bassée north to the Lys.[17]

Battle

14–20 October

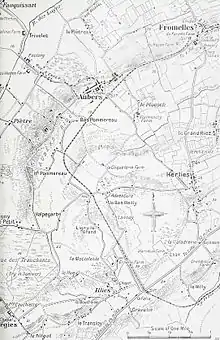

On 14 and 15 October, II Corps attacked on both sides of La Bassée Canal and German counter-attacks were made each night. The British managed short advances on the flanks, with help from French cavalry but lost 967 casualties. From 16 to 18 October, II Corps attacks pivoted on the right and the left flank advanced to Aubers, against German opposition at every ditch and bridge, which inflicted another thousand casualties. Givenchy was recaptured by the British on 16 October, Violaines was taken and a foothold established on Aubers Ridge on 17 October; French cavalry captured Fromelles. On 18 October, German resistance increased as the German XIII Corps arrived, reinforced the VII Corps and gradually forced the II Corps to a halt. On 19 October, British infantry and French cavalry captured Le Pilly (Herlies) but were forced to retire by German artillery-fire.[18]

The fresh German 13th Division and 14th Division arrived and began to counter-attack against all of the II Corps front. At the end of 20 October, the II Corps was ordered to dig in from the canal near Givenchy, to Violaines, Illies, Herlies and Riez, while offensive operations continued to the north.[18] The countryside was flat, marshy and cut by many streams, which in many places made trench digging impractical, so breastworks built upwards were substituted, despite being conspicuous and easy to demolish with artillery-fire. (It was not until late October that the British received adequate supplies of sandbags and barbed wire.) The British field artillery was allotted to infantry brigades and the 60-pounders and howitzers were reserved for counter-battery fire.[19] The decision to dig in narrowly forestalled a German counter-offensive which began on 20 October, mainly further north against the French XXI Corps and spread south on 21 October, to the 3rd Division area.[20]

21 October

The II Corps brigades in line (from south to north) were the 15th, 13th, 14th, 7th, 9th and 8th; at 7:00 a.m. the Germans attacked through a mist, mainly opposite the 7th and 9th brigades from Le Transloy to Herlies and surprised one company, forcing it back. The Germans widened the breach on the right of the 7th Brigade, but flanking units repulsed the German attackers. Elsewhere, the Germans maintained an extensive bombardment against the 9th Brigade but they did not attack, and one battalion at Violaines was able to fire in enfilade at German infantry, as they crossed its front towards Le Transloy. An infantry company and the 7th Brigade Signal Section engaged the Germans at 150 yd (140 m) as they apparently lost direction in the mist and more troops arrived to close the gap. As the mist dispersed British artillery fired on the German infantry who retreated at speed. A British counter-attack was made at 11:00 a.m. which retook most of the lost trenches. Most of the British reserves had been committed but German attacks at 2:30 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. were also repulsed, troops from all three regiments of the German 14th Division and one from the 13th Division being identified.[21]

At 6:30 p.m. news of the retirement of the 19th Brigade from Le Maisnil arrived and the 3rd Division was ordered back from Herlies and Grand Riez for about 1 mi (1.6 km) to a line from Lorgies to Ligny and south of Fromelles, the junction with a French cavalry unit, which improved the line in the 8th Brigade area; later on the left flank of the 14th Brigade moved back to link with the 3rd Division at Lorgies. On 21 October II Corps had 1,079 casualties. During the fighting Smith-Dorrien had ordered the digging of a reserve line which was about 2 mi (3.2 km) in the rear on the northern flank, where the danger of envelopment was greatest. The line ran from east of Givenchy, east of Neuve-Chapelle to Fauquissart on ground easier to defend but had little barbed wire and the ground was too marshy for deep dugouts. The engineers of the 3rd and 5th divisions prepared the defences, with help from French civilians. Next day the French cavalry were driven from Fromelles and a retirement to the new line was agreed by French and Smith-Dorrien, for the night of 22/23 October. French ordered elements of the Lahore Division to move to Estaires, behind the left (northern) flank of II Corps, to support the French II Cavalry Corps (Général Louis Conneau).[22]

22–25 October

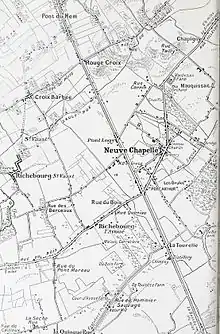

Early on 22 October, the British were forced out of Violaines and German attacks began along all of the 5th Division front.[23] On the night of 22/23 October, II Corps retired its left (northern) flank, to a line which had been reconnoitred from La Bassée Canal east of Givenchy to La Quinque Rue, east of Neuve-Chappelle and on to Fauquissart. A lack of labour, tools and barbed wire meant that the troops found little more than an outline of the position and began to dig in. The 3rd Division was on the left flank, at the junction with the French II Cavalry Corps and the 19th Brigade, which had closed a gap with the III Corps. The Germans spent 23 October bombarding the old British positions and probing forward, as the Lahore Division (Lieutenant-General Henry Watkis) reached Estaires, which had been made the assembly point for the Indian Corps, to be convenient to support II Corps or III Corps as necessary.[lower-alpha 3] The Jullundur Brigade relieved the II Cavalry Corps on 23/24 October, from the II Corps left flank at Fauquissart to the 19th Brigade at Rouges Bancs, which created a homogeneous British line from Givenchy northwards to Ypres.[25]

Opposite the Anglo-French south of the British III Corps, was part of the German XIV Corps and the VII, XIII, XIX and I Cavalry Corps. At 2:00 a.m., on 24 October, German artillery began a bombardment and just after dawn many German infantry were seen approaching the 3rd Division positions in the north.[lower-alpha 4] The German troops were easily visible and repulsed by artillery-fire before they reached the British front line. German attacks were suspended until dusk when an attack began south of Neuve-Chapelle on the right flank of the 3rd Division, until after midnight, eventually being repulsed, with many casualties. In the early hours of 25 October, German infantry were able to overrun some British trenches but were forced out by hand-to-hand fighting and at 11:00 a.m., the trenches were overrun again until reinforcements from the 9th Brigade forced the Germans back. On the left flank of the 3rd Division the 8th and Jullundur brigades were attacked from 9:00 p.m. on 24 October and the left flank battalion of the 8th Brigade was forced back. The flanking units fired into the area and a counter-attack at midnight by the brigade reserve battalion, managed to restore the position in costly fighting. Many German troops of the 14th and 26th divisions were killed in the attacks and several prisoners taken.[27]

By morning, the II Corps headquarters staff were relieved, that despite 13 days of battle, exhaustion and the loss of many pre-war regulars and experienced reservists, a determined German attack had been defeated. The corps front was not attacked on 25 October but German guns accurately bombarded the British positions, with assistance from observation aircraft, flying in clear weather. German infantry kept 700–900 yd (640–820 m) back, except for areas in front of the 5th Division. Some positions were evacuated during daylight hours to escape German shelling and engineers collected fence posts and wire from farmland, ready to build obstacles in front of the British positions overnight. Smith-Dorrien forecast a lull in German attacks but requested reinforcements from French who agreed, because a defeat at La Bassée would compromise offensive operations in Belgium. A cavalry brigade, some artillery and an infantry battalion were moved to Vieille Chappelle behind the 3rd Division, two 4.7-inch gun batteries and Jellicoe a Royal Navy armoured train, were sent and the field gun ammunition ration was doubled to 60 shells per gun per day. Maud'huy added two more battalions to the one in Givenchy and Conneau moved the II Cavalry Corps behind the 3rd Division flank. About 2,000 British replacements had arrived by 27 October, which brought the infantry battalions up to about 700 men each.[28]

26–27 October

There was much German patrolling before dawn on 26 October and at sunrise the Germans attacked north of Givenchy, having crept up in the dark but were repulsed by small-arms fire aimed at sounds because the British had no Very pistols or rockets. Later on, French reinforcements arrived so that the British battalion could move into divisional reserve, with the two already withdrawn. Another German attack began in the afternoon on the left of the 5th Division, in which the German infantry broke into the British trenches before being annihilated. Another attack began near Neuve-Chappelle at 4:00 p.m. against the extreme left flank of the division and the right of the 3rd Division, after an accurate artillery bombardment. The British infantry had many casualties and some units withdrew from their trenches to evade the German artillery-fire. A battalion was broken through and the village was occupied but the flanking units enfiladed the Germans until the reserve company, down to 80 men held the western exits and forced the Germans back into the village, which was on fire.[29]

At 6:00 p.m. a reserve battalion and 300 French cyclists reached the area as did the rest of the brigade reserve but the darkness and disorganisation of the troops took time to resolve. A counter-attack by three companies began from the west after dark and pushed the Germans back to the former British trenches east of the village. Attacks were then postponed until dawn and Smith-Dorrien Trench, a new line east of the village was dug and linked to the defences north and south of the village. British casualties were severe and when French visited II Corps headquarters on 26 October, more reinforcements were promised and French ordered a defensive front to be maintained, with local attacks to keep German troops from moving from the area into Belgium. When dawn broke, the situation at Neuve-Chapelle was seen to be worse than expected, since the Germans had consolidated positions in outlying buildings and the old British trenches. A battalion attempted to recapture the trenches at 7:30 a.m. but the Germans got round a flank and almost surrounded the battalion; the last two companies lost 80 per cent of their men retreating through the village.[30]

North of Neuve-Chapelle the counter-attack on a triangle of houses nearby did not begin until 10:00 a.m., such was the confusion. Elements of three battalions and the French cyclists, with support from four British and seven French cavalry batteries were quickly stopped by German machine-gun fire and snipers, who had been able to consolidate the captured houses. At 11:00 a.m., two companies and 600 chasseurs à pied arrived and six companies of the Indian Corps were dispatched. German activity opposite the rest of the 3rd Division was slight but the Jullundur Brigade to the north was attacked several times, as the German 14th Division massed in Bois du Biez, about 0.5 mi (0.80 km) from Neuve-Chapelle. By 1:30 p.m. the British-French counter-attack had pushed forward north of the village and British troops held out in Smith-Dorrien Trench to the east. The German attack began at 2:30 p.m. and quickly got behind the defenders, who were almost cut off an hour later and were pursued through the village, the two battalions involved being reduced to about 500 men including replacements.[31]

Some of the German troops pressed on through the village but 500 yd (460 m) to the west, met a party of about 250 British troops, who pushed them back to the village and frustrated several attempts to advance again. The Germans shifted the weight of the attack to the south and got round the left flank of the neighbouring battalion, which pulled the flank back at right angles. German rifle-fire from behind killed the commander and adjutant but the survivors held on until the 9th Bhopal Infantry battalion arrived, got behind the German flank and drove them back to the village. The 20th and 21st companies of the 3rd Sappers and Miners, the last British reserve, were sent to link the 9th Bhopal and the Northumberland fusiliers to the north of the village. Brigadier-General Frederick Maude the 14th Brigade commander to the south, had sent his reserve battalion which arrived after the 9th Bhopal and moved, north to make a flank attack on the Germans in the village but night fell before the troops were ready.[32]

Major-General Thomas Morland the 5th Division commander, ordered Maude to lead another counter-attack reinforced by ten more companies. Maude cancelled the attack when he found that the British line had been restored and the village could only be attacked from the north-west. On the northern flank of the village, the British counter-attack which had begun at 1:30 p.m. had reached the western fringe of the village after an hour but had then been pinned down by machine-gun and sniper fire from the many houses thereabouts. Around 5:00 p.m., about 400 men of the 47th Sikhs arrived but were insufficient to restart the advance. German small-arms fire enfiladed both flanks and every other reinforcement had been sent to fill the gap at Neuve-Chapelle. The counter-attack was ended and after dark the troops dug in around the west end of the village. Later that night the 3rd Division commander, Major-General Colin Mackenzie, approved the decision to relinquish the village and the survivors of the three British battalions, fewer than 600 men, were collected at Richebourg St Vaast with the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, which had arrived from the north. The new line curved around Neuve-Chapelle, with no man's land reduced to 100 yd (91 m).[33][lower-alpha 5]

28 October

The II Corps orders to maintain a defensive front but to exploit local opportunities for attack were echoed by GHQ and French, Smith-Dorrien and Willcocks met to arrange for II Corps to be relieved by the Indian Corps. French wanted the corps to rest for several days and then be the BEF reserve. The 3rd Division was ordered by Smith-Dorrien to recapture Neuve-Chapelle, because the German position there threatened the inner flanks of the 3rd and 5th divisions. Every second available man was made available to the Corps Chief Engineer (Major-General C. Mackenzie) to dig a second line and Smith-Dorrien oversaw the preparations at the 3rd Division headquarters for the counter-attack. The 7th Brigade (Brigadier-General McCracken) was to conduct the attack with support from the Indian Corps troops nearby, the 24th Brigade on the right flank and the 2nd Cavalry Brigade at Richebourg St Vaast, though down to 400 men, was made ready to follow up the attack on the right flank. To the north on the left flank a 6th Division battalion, French chasseurs and cyclists from the II Cavalry Corps and a battalion of the 9th Brigade (Brigadier-General Shaw) were also to support the attack.[35]

Fog led to the attack being postponed until 11:00 a.m., after a short bombardment from thirteen Anglo-French batteries. After fifteen minutes the bombardment was moved 500 yd (460 m) forward, ready for the infantry advance but disorganisation, language difficulties and exhaustion led only about four companies advancing, despite the presence of 3rd Division staff officers acting as liaison officers. The flank support was also inadequate due to German return fire and exhaustion, soldiers falling asleep as they fired. Two companies of the 47th Sikhs and the 20th and 21st Sappers and Miners attacked, as the 9th Bhopal Infantry was quickly forced under cover on the right. The attackers advanced by fire and movement over 700 yd (640 m) of flat ground, drove the Germans out of the village and reached the eastern and northern fringes. German artillery and machine-gun fire supported constant German counter-attacks, which eventually forced the Indians to retire despite the German fire, the 47th Sikhs losing 221 of 289 men and the Sappers losing 30 per cent of their manpower in casualties. The 9th Bhopal Infantry also retired from a captured trench, which led to two flanking companies being overrun.[36]

During the attack the 2nd Cavalry Brigade occupied the Indian jumping-off trenches and gave covering fire during the retreat. The last cavalry reserve moved forward, to stop the German infantry debouching from Neuve-Chapelle advancing further south, until 2:00 p.m. when the last 300 men of an infantry battalion arrived. Further north the chasseurs and a British infantry battalion had advanced over much more difficult terrain and were too late to reinforce the Indian troops when their advance faltered. When the Indian troops retired, the attack was stopped and trenches west of the village were re-occupied. North of the village, the 9th Brigade was bombarded and sniped all day and but stood fast. Around 1:00 p.m. the Germans attacked south of the village, after five hours of bombardment, against the two northernmost battalions of the 13th Brigade, while other troops kept up the attack on the 2nd Cavalry Brigade and attached infantry.[37] At 5:00 p.m. the Germans made a maximum effort along all of the attack front, advancing to within 100 yd (91 m) of the British positions in places. Exhausted troops were brought back into line to reinforce the cavalry and the German attacks diminished until 9:00 p.m., when a final attack was made in the south.[38]

29 October

During the night the cavalry were relieved and a small salient opposite Bois du Biez relinquished to straighten the line; a patrol entered Neuve-Chapelle and found it empty but during the day German bombardments and probing attacks were received all along the line. The junction of the 13th and 14th brigades near La Quinque Rue and Festubert was attacked at about 4:00 a.m., when the Germans moved quietly forward in mist but were then caught by artillery and small arms fire. A second attack just to the north occupied a British trench and at noon another attack was attempted after French shells were seen to drop short. This attack was also repulsed and a brief respite followed until after dark when German troops moved stealthily into the village. In the subsequent fighting they were repulsed three times. Successive attacks on the Indian Corps troops further north were mostly defeated by artillery-fire. During the day, most of the Indian Corps arrived in the area and began to relieve the remnants of II Corps overnight.[39]

30 October – 2 November

Movement forward to the British positions was difficult in daylight, due to a lack of communication trenches, so Indian troops moved along wet ditches in the dark and conducted the relief over two nights. Exchanging two battalions took about 2½ hours and a German attack on 30 October pushed a Gurkha battalion back and exposed the flank of the neighbouring battalion until a counter-attack could be arranged to regain the line. Early on 31 October, Willcocks, the Indian Corps commander, took over from Smith-Dorrien from Givenchy to Fauquissart, who left about ten severely depleted infantry battalions and most of the corps artillery behind. The II Corps troops had been promised ten days to rest but troop movements towards Wytschaete began immediately, some on foot and some by bus. On 1 November the last seven battalions in the area were sent north to Bailleul behind III Corps. The 5th Division artillery was sent north to the Cavalry Corps by 2 November and the remaining II Corps engineer companies built more field fortifications.[40]

Aftermath

Analysis

The French had been able to use the undamaged railways behind their front to move troops more quickly than the Germans, who had to take long detours, wait for repairs to damaged tracks and replace rolling stock. The French IV Corps moved from Lorraine on 2 September in 109 trains and had assembled by 6 September.[41] The French had been able to move troops in up to 200 trains per day and use hundreds of motor-vehicles which were co-ordinated by two staff officers, Commandant Gérard and Captain Doumenc. The French used Belgian and captured German rail wagons and the domestic telephone and telegraph systems.[42] The initiative held by the Germans in August was not recovered as all troop movements to the right flank were piecemeal. Until the end of the Siege of Maubeuge (24 August – 7 September) only the single line from Trier to Liège, Brussels, Valenciennes and Cambrai was available and had to be used to supply the German armies on the right as the 6th Army travelled in the opposite direction, limiting the army to forty trains a day which took four days to move a corps. Information on German troop movements from wireless interception enabled the French to forestall German moves but the Germans had to rely on reports from spies, which were frequently wrong. The French resorted to more cautious infantry tactics, using cover to reduce casualties and a centralised system of control as the German army commanders followed contradictory plans. The French did not need quickly to obtain a decisive result and could concentrate on preserving the French army.[43]

In 1925, the British official historian James Edmonds, wrote in the History of the Great War that from 13 to 31 October, the twelve 3rd Division battalions had been opposed by thirteen German infantry regiments, four Jäger battalions and 27 cavalry regiments. The British troops had succeeded in repulsing German attacks through endurance and fire-discipline, which had multiplied the effect of a small number of troops.[38] The German 6th Army had been reinforced and originally been intended to break through from Arras to La Bassée and Armentières, until 29 October when all available heavy artillery was transferred north for the Battle of Gheluvelt. Attacks against II Corps were reduced to holding operations and the front opposite the French at Arras was kept passive. When the Indian Corps took over, the German offensive in the area had almost ended.[44] Edmonds wrote that in defence, soldiers sheltered in improvised positions with little protection from artillery and little barbed wire. Much of the country was wooded, which obscured large areas of the front from aeroplane observers, who spent more time grounded by the October weather. The Allied force was made up of Belgian, French and British army units and faced a homogeneous opponent with unity of command but the main German advantage was in heavy artillery and trench warfare equipment, much of which did not exist in the Allied armies.[45]

Casualties

| Month | Losses |

|---|---|

| August | 14,409 |

| September | 15,189 |

| October | 30,192 |

| November | 24,785 |

| December | 11,079 |

| Total | 95,654 |

The II Corps had c. 14,000 casualties, from 12 to 31 October. The 3rd Division had 5,835 losses, with the 8th and 9th brigades reduced by about 50 per cent. The 5th Division casualties were similar and the Indian Corps up to 31 October had 1,565 casualties.[47] On 31 October II Corps had only 14,000 men of the original 24,000 man establishment, of which c. 1,400 men were inexperienced drafts. The Germans recorded 6,000 casualties during the battles with II Corps.[48]

Subsequent operations

II Corps was withdrawn for ten day's rest, from the night of 29/30 October and relieved by the Indian Corps but within days, most of its battalions had to be sent to I and III corps as reinforcements.[49] Smith-Dorrien returned to England on 10 November and Willcocks assumed command of the 14th Brigade of the 5th Division, which acted as a mobile reserve.[50] The Indian Corps battalions came under much shellfire during the relief and remained in the front-line trenches, instead of retreating further back temporarily, a practice which had been adopted by experienced units. On 2 November, a bigger German attack north-west of Neuve-Chapelle drove a Gurkha battalion back until local counter-attacks recovered the ground by 5 October and the old trenches were filled in and abandoned.[51]

By 3 November, the Indian Corps had suffered 1,989 casualties along its 8 mi (13 km) front. Some historians have written that c. 65 per cent of Indian casualties were self-inflicted wounds, not always punished by court martial but a study by Sir Bruce Seton in 1915, found no evidence to support such an allegation.[48][52] On 7 November, the 14th Brigade relieved the 8th Brigade near Laventie until 15 November.[50] Winter operations from November 1914 to February 1915 in the II Corps area took place and were called the Defence of Festubert (23–24 November), Defence of Givenchy (20–21 December), the First Action of Givenchy (25 January 1915) and the Affairs of Cuinchy.[53]

Notes

- According to the findings of the Battles Nomenclature Committee Report (9 July 1920), four simultaneous battles occurred in October and November 1914. The Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November) from the Beuvry–Béthune road to a line from Estaires to Fournes, the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November) from Estaires to the Douve river, the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) from the Douve to the Ypres–Comines Canal and the Battles of Ypres (19 October – 22 November), comprising the Battle of Langemarck (21–24 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October) and the Battle of Nonne Bosschen (11 November), from the Ypres–Comines Canal to Houthulst Forest. James Edmonds, the British official historian, wrote that the II Corps battle at La Bassée could be taken as separate but that the other battles from Armentières to Messines and Ypres, were better understood as a battle in two parts, an offensive by III Corps and the Cavalry Corps from 12 to 18 October, against which the Germans retired and the offensive by the German 6th and 4th armies 19 October – 2 November, which from 30 October mainly took place north of the Lys at Armentières, from when the battles of Armentières and Messines merged with the Battles of Ypres.[1]

- British order of battle, II Corps: 2nd Cavalry Brigade, 3rd and 5th divisions. Indian Expeditionary Force A, Indian Corps: Lahore Division less the Sirhind Brigade, Meerut Division and the Secunderabad Cavalry Brigade.[10] Indian Army units were numbered but these were not used in France, to obviate confusion with similarly numbered metropolitan units.[11]

- The division was sent to the II Corps area but was incomplete, the battalions of the Jullundur Brigade having only 700–800 men each, the Ferozepore Brigade having been detached to the Cavalry Corps (Lieutenant-General Edmund Allenby) and the Sirhind Brigade still being in Egypt.[24]

- The German attack was part of a larger operation by the 6th Army from La Bassée canal to the Lys at Frélinghien.[26]

- On the rest of the II Corps front, there had been much German artillery-fire on 27 October but little infantry action. Exhaustion and casualties left the corps in an extremely weakened state with no prospect of relief. Further north, the Jullundur Brigade had been attacked during mid-afternoon but was repulsed by the Indian infantry and artillery-fire from British and French artillery. Another attack at 9:00 p.m. was defeated and four companies of Chasseurs à pied, with three dismounted cavalry squadrons from the II Cavalry Corps, were moved into reserve behind the brigade. German prisoners had been taken from eight regiments of three corps on the 3rd Division front, along with the 14th Division troops. Gas shell was used on 27 October, when 3,000 × 105 mm shrapnel shells carrying an additional eye and nose irritant (Dianisidin) were fired at the British, although the effect was so insignificant that no-one noticed.[34]

Footnotes

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 125–126.

- Foley 2007, p. 101.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 98–100.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 269–270.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 73–74.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 74–76.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 268–269.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 69–70.

- Edmonds 1926, p. 408.

- James 1990, p. 4.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 92.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 68–71.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 77–81.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 122.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 168.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 224.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 259–260.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 81–87.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 206.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 87.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 87–88.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 88–89.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 89–90.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 207.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 205–207.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 208.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 205, 208–209.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 209–211.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 211.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 212–213.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 213–214.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 214–215.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 215.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 216.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 216–217.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 217–219.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 219.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 220.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 220–221.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 221–222.

- Doughty 2005, p. 100.

- Clayton 2003, p. 62.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 265–266.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 223–224.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 460–462.

- War Office 1922, p. 253.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 222–223.

- Beckett 2003, pp. 139–140.

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 221–223.

- Hussey & Inman 1921, p. 47.

- Edmonds 1925, p. 223.

- Seton 1915, p. 8.

- James 1990, p. 6.

References

- Beckett, I (2003). Ypres: The First Battle, 1914 (2006 ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 978-1-4058-3620-3.

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35949-3.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich Von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Hussey, A. H.; Inman, D. S. (1921). The Fifth Division in the Great War. London: Nisbet. ISBN 978-1-84342-267-9. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 978-0-948130-18-2. OCLC 250857010.

- Seton, Bruce (1915). An Analysis of 1,000 Wounds and Injuries Received in Action, with Special Reference to the Theory of the Prevalence of Self-Infliction (Secret). no ISBN. London: War Office. IOR/L/MIL/17/5/2402. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914–1920. London: HMSO. 1922. OCLC 610661991. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

Further reading

- Edmonds, J. E. (1922). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914 Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. Vol. I (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1915: Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-218-0.

- Gleichen, A. E. W. (1917). The Doings of the Fifteenth Infantry Brigade, August, 1914 to March, 1915. Edinburgh: Blackwood. OCLC 810917679. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- McNish, R. (1990) [1977]. Iron Division: The History of the 3rd Division 1809–1989 (rev. Galago Publishing ed.). BFPO, Germany: 3rd Armoured Division. ISBN 978-0-946995-97-4.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Willcocks, J. (1920). With the Indians in France. London: Constable. OCLC 1184253. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Wyrall, E. (1921). The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. Vol. I. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. OCLC 827208685. Retrieved 8 August 2014.