Operations on the Ancre, January–March 1917

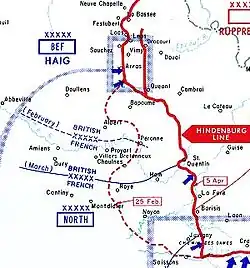

Operations on the Ancre took place from 11 January – 13 March 1917, between the British Fifth Army and the German 1st Army, on the Somme front during the First World War. After the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November 1916), British attacks on the Somme front stopped for the winter. Until early January 1917, both sides were reduced to surviving the rain, snow, fog, mud fields, waterlogged trenches and shell-holes. British preparations for the Battle of Arras, due in the spring of 1917, continued.

| Operations on the Ancre, January–March 1917 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The First World War | |||||||||

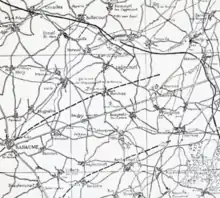

The Western Front, 1917 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

British Empire French Empire |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Robert Nivelle Douglas Haig Hubert Gough Henry Rawlinson |

Erich Ludendorff Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern Max von Gallwitz | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Fifth Army | 1st Army | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 2,151 (incomplete) | 5,284 prisoners | ||||||||

The Fifth Army was instructed by the commander in chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, to make systematic attacks to capture portions of the German defences to pin down German troops. Short advances could progressively uncover the remaining German positions in the Ancre valley to ground observation, threaten the German hold on the village of Serre to the north and bring German positions beyond into view. Artillery-fire could be directed with greater accuracy by ground observers and make German defences untenable.

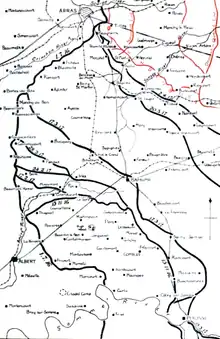

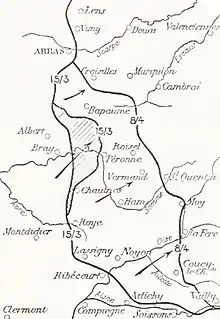

A more ambitious plan for the spring was an attack into the salient that had formed north of Bapaume, during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. As soon as the ground dried, the attack was to be made northwards from the Ancre valley and southwards from the original front line near Arras further north, to meet at St Léger and combine with the offensive due at Arras. British operations on the Ancre from 11 January to 22 February 1917 forced the Germans back 5 mi (8.0 km) on a 4 mi (6.4 km) front, ahead of the scheduled German retirements of the Alberich Bewegung (Operation Alberich) and eventually took 5,284 prisoners.

On 22/23 February, the Germans withdrew another 3 mi (4.8 km) on a 15 mi (24 km) front. The Germans then withdrew from much of Riegel I Stellung (Reserve Position I) to Riegel II Stellung (Reserve Position II) on 11 March, which went unnoticed by the British until dusk on 12 March, forestalling a British attack. Unternehmen Alberich, the main German withdrawal from the Noyon salient south of the Somme, towards the Hindenburg Line, commenced on schedule on 16 March.

Background

German defences

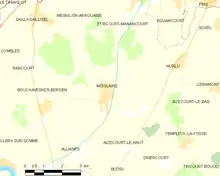

By the end of 1916, the German defences on the south bank of the Ancre valley had been pushed back from the original front line of 1 July 1916 and were based on the sites of fortified villages connected by networks of trenches, most on reverse slopes sheltered from observation from the south and obscured from the north by convex slopes. On the north bank, the Germans still held most of the Beaumont-Hamel spur, beyond which to the north were the original front line defences, running west of Serre and then northwards to Gommecourt and Monchy-au-Bois. The Germans had built Riegel I Stellung (Reserve Position I), a double line of trenches and barbed-wire several miles further back from Essarts to Bucquoy, west of Achiet-le-Petit, Loupart Wood, south of Grévillers, west of Bapaume, Le Transloy to Sailly-Saillisel as a new second line of defence along the ridge north of the Ancre valley.[1]

On the reverse slope of the ridge, Riegel II Stellung (Reserve Position II) ran from Ablainzevelle to west of Logeast Wood, west of Achiet-le-Grand, western outskirts of Bapaume, Rocquigny, Le Mesnil en Arrousaise to Vaux Wood.[1] Riegel III Stellung (Reserve Position III) branched from Riegel II at Achiet-le-Grand clockwise around Bapaume, then south to Beugny, Ytres, Nurlu and Templeux-la-Fosse.[1] The first two lines were also known as the Allainesstellung and Arminstellung by the Germans and had various British titles (Loupart Line, Bapaume Line, Transloy Line and Bihucourt Line, the third line was known as the Beugny–Ytres Switch).[2] The 1st Army held the Somme front from the River Somme north to Gommecourt and had a similar number of troops to the British opposite, with ten divisions in reserve.[2][lower-alpha 1] On the night of 1/2 January, a German attack captured Hope Post near the Beaumont Hamel–Serre road, before being lost along with another post on the night of 5/6 January.[3]

British positions

The Fifth Army held about 10 mi (16 km) of the Somme front in January 1917, from Le Sars westwards to the Grandcourt–Thiepval road, across the Ancre east of Beaucourt, along the lower slopes of the Beaumont-Hamel spur, to the original front line south of the Serre road, north to Gommecourt Park. The right flank was held by IV Corps up to the north side of the Ancre river, with the XIII Corps on the north bank up to the boundary with the Third Army. II Corps and V Corps were in reserve resting, training and preparing to relieve the corps in line around 7–21 February, except for the divisional artilleries, which were to be joined by those of the relieving divisions.[4][lower-alpha 2]

An advance to close up to the Le Transloy–Loupart line (Riegel I Stellung), which ran from Essarts to Bucquoy, west of Achiet le Petit, Loupart Wood, south of Grévillers, west of Bapaume, Le Transloy to Sailly Saillisel, had been the first objective of British operations in the Ancre valley after the capture of Beaumont Hamel in late 1916. Operations began with an attack on 18 November, before the deterioration of the ground made operations impossible. Ground had been gained on a 5,000 yd (2.8 mi; 4.6 km) front south of the Ancre and positions improved on Redan Ridge on the north bank. Over the winter, the Fifth Army submitted plans to General Headquarters (GHQ), which were settled in mid-February, after Joffre was replaced by General Robert Nivelle and the changes of strategy caused by the French decision to fight a decisive battle on the Aisne. The obvious difficulties of the Germans on the Ancre front, made it important to prevent the Germans from withdrawing to the new defences being built behind the Noyon salient (eventually known as the Hindenburg Line/Siegfriedstellung) in their own time. A retirement could disrupt the British offensive at Arras and Franco-British planning gained urgency as a German withdrawal became likely in February and March, according to the results of air reconnaissance, agent reports and gleanings from prisoners.[5]

Reaching a good position for an attack on the Bihucourt line (Riegel II Stellung) which ran from Ablainzevelle to west of Logeast Wood, west of Achiet le Grand, western outskirts of Bapaume, Rocquigny, le Mesnil en Arrousaise to Vaux Wood, the Fifth Army objective was to be attacked three days before the Arras offensive and the army then to advance to St Léger, to meet the Third Army and trap the Germans in their positions south-west of Arras. The first stage was to be an attack on 17 February, in which II Corps was to capture Hill 130. Gird Trench and the Butte de Warlencourt was to be captured by I Anzac Corps on 1 March and Serre was to be taken by V Corps on 7 March, which would then extend its right flank to the Ancre, to relieve the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division of II Corps and capture Miraumont by 10 March. These operations would lead to the attack on the Bihucourt line by II Corps and I Anzac Corps. These arrangements were maintained until 24 February, when German local withdrawals in the Ancre valley, required the Fifth Army divisions to make a general advance to regain contact.[6]

Prelude

51st (Highland) Division

.jpg.webp)

The state of the ground on the Somme front became much worse in November 1916, when constant rain fell and the ground which had been churned by shellfire since June, turned to deep mud again. (Some witnesses considered that the state of the ground was worse than at Ypres a year later.) The ground in the Ancre valley was in the worst condition, a wilderness of mud, flooded trenches, shell-hole posts, corpses and broken equipment, overlooked and vulnerable to sniping from German positions. Little could be done beyond holding the line and frequently relieving troops, who found the physical and mental strain almost unbearable. Supplies had to be moved up by soldiers at night, to avoid sniping by German infantry and artillery-fire. Horses in transport units were used as pack animals and died when the oat ration was reduced to 6 lb (2.7 kg) per day. In January the weather slightly improved and on 14 January, the temperature fell enough to freeze the ground.[7]

On the south side of the Ancre valley near Courcelette, the 51st (Highland) Division took over from the 4th Canadian Division on 27 November. The division had only just been relieved from the line on the north bank, after the Battle of the Ancre (13–18 November 1916) with very little time for rest. Constant rain wet the ground so badly, that horses drowned and men became stuck up to their waists; in December ropes were issued to drag soldiers out of the mud. New trenches collapsed as they were dug and the front and support lines were held by shell-hole posts, which became islands of squalor. Duckboards and ration boxes used as platforms sank under the mud; cooking became impossible and movement in daylight suicidal. There were epidemics of dysentery, trench foot and frostbite; old wounds opened. Morale plummeted and moving about after dark led to working parties, runners, reliefs and ration parties getting lost and wandering around until exhausted. No man's land was not wired on this part of the front and British and German troops blundered into the wrong positions, Germans being taken prisoner on six occasions.[lower-alpha 3] Some dug-outs in Regina Trench were usable but conditions in the artillery lines were as bad as the front line, with ammunition being delivered by pack horse under German artillery fire. "Elephant" shelters (the materials for which took ten men to carry forward and 24 hours to build) were placed in the front-line, sunk below trench and shell-hole parapets. Larger shelters were dug into the sides of roads further back and only a minimal number of troops kept in the front zone.[9]

After three weeks' work, positions in the front line had been improved and a frost hardened the ground, then a thaw made the ground worse than before. The 51st (Highland) Division stores obtained enough gumboots for an infantry brigade but many were lost in the mud as men struggled to get free. The division wore highland kilts, which left the top of the leg bare underneath and their boot edges chafed the skin and caused septic sores, until 6,000 pairs of trousers were issued. Wearing the boots and standing for long periods made men's feet swell and walking became almost impossible. Buses were brought up to Pozières to collect soldiers as they straggled back from the front line during a relief. Food containers proved too heavy to carry the 2,000 yd (1.1 mi; 1.8 km) to the front line and were replaced by Tommy cookers, which were cans of solidified alcohol to heat tinned food. Quartermasters improvised large numbers of extra cookers, so that the troops in the line could eat hot food when they pleased but the improvements made little difference to sickness. The division began to relieve battalions after 48 hours, with 24 hours' rest before and after each period in the line. On 11 December, the divisional front was reduced to two battalions, with the front of each battalion area being held by a company and two Lewis-gun crews. Company strengths had declined to 50–60 men, so thinly spread that a stray German was taken prisoner near a brigade headquarters, having seen no sign of British troops until he was captured. In December and January, the division suffered 439 casualties to enemy action, far fewer than those due to the weather and illness; the division was relieved by the 2nd Division on 12 January.[10]

2nd Division

The 2nd Division, also transferred from the north side of the Ancre valley, took over from the Highlanders on 13 January, on a front of 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km), 1,200 yd (1,100 m) south of the village of Pys. The front line consisted of 18 infantry posts and support positions held by ten platoons, with nothing until three platoons in Courcelette and two companies nearby. Ironside Avenue, a communication trench, ran forward 800 yd (730 m) towards the front line but was full of mud and impassable. Brushwood tracks, unusable during the day, continued the route towards the front line. Two battalions took over the front posts, with two more back towards Ovillers and La Boisselle, with the 15th (Scottish) Division on the right and the 18th (Eastern) Division on the left. The 2nd Division continued to consolidate the positions begun earlier, large working parties labouring non-stop to dig out, clean and pump trenches, fit duckboards and provide overhead cover for the infantry posts; tramways were built further back by engineers. Both sides were quiet during the rest of January, until the Germans attempted a raid which was stopped by machine-gun fire before the raiders had advanced past the German barbed wire; on the north side of the valley, British troops captured the rest of the Beaumont Hamel spur. By the end of the month conditions were better, although snowstorms covered the few landmarks and relieving parties frequently got lost. There was little artillery fire in the divisional areas but much German aircraft activity; British reconnaissance aircraft managed to photograph the front line on 29 January, giving the divisional commander the first accurate information about it. The freeze lasted for about five weeks until mid-February, which made movement of carrying-parties much easier as preparations to attack were being made.[11]

7th Division

On the north bank of the Ancre the 7th Division returned to the line after a month of rest and reorganisation in Flanders. It had marched 82 mi (132 km) south in rain and fog and returned to the line on 23 November, relieving the 32nd Division and the right of the 37th Division along New Munich Trench. The trench ran north-west to south-east below the crest of Beaumont Hamel spur; Beaucourt Trench ran east from the south end of New Munich Trench. The British line was parallel to the German end of Munich Trench and Muck Trench. Conditions were worse if possible, than those on the south side of the Ancre valley, causing much sickness despite precautions like rubbing whale oil into the feet to prevent trench foot and bringing dry socks up with the rations. One battalion had 38 men sick after a short period in the line. The temperature dropped several times in December, which began to harden the ground but this brought torrential rain, an even worse ordeal. Snipers caused many British casualties and on one trench relief, the mud was so bad that a special rescue-party had to be sent to dig out troops caught in the mud. Despite swift medical attention, a large number of men had to be taken to hospital and one soldier died of exposure.[12]

The area was covered with trenches, many of which were derelict, damaged, half-built or obliterated by artillery-fire. Identifying the course of the front line or relating it to the map was impossible, as was the reconstruction of the front line, because trenches collapsed as soon as they were dug. Despite the conditions, raids were mounted by both sides and a party of about 100 Germans was repulsed from New Munich Trench on 25 November. Despite the conditions, New Munich Trench was extended to the north by the British and another 250 yd (230 m) was dug to the south, in preparation for an attack on Munich Trench as soon as conditions allowed. The British line was held by posts about 30 yd (27 m) apart during the day and on 29 November a German raid on one of the outposts failed. At the end of December, there was a sudden increase in the number of German prisoners being taken, because a new German division had arrived, men got lost in the fog and stumbled into British positions and partly because of an unusual willingness to surrender. Twenty Germans were captured on 1 January, 29 on 2 January and another 50 prisoners were taken during the week, many of whom were deserters.[13]

Raiding continued and on 1 January, two officers on the way to Hope Post with the rum ration met a German attack coming down Serre Trench and had to struggle back to Despair Post. A hurried counter-attack was defeated by German machine-gun fire and another attempt was postponed until the evening of 5 January. At 5:15 p.m., five hundred 9.2-inch, two hundred 8-inch and two hundred and fifty 6-inch howitzer shells were fired at the post in fifteen minutes. At 5:30 p.m. fifty British troops attacked up Serre Trench and along the ground on either side as fast as they could through the mud, re-capturing the post, taking nine prisoners for one casualty. An attack by the 3rd Division on Post 88 to the left at the same time also succeeded. German artillery-fire was so severe that the British were forced out but were able to return after the bombardment and forestall German infantry, defending the post until they ran out of hand-grenades and withdrew; when a fresh supply of grenades arrived, the British took the post again and consolidated.[14]

Trench raid, 4/5 February

A 2nd Division battalion was ordered to prepare a raid for the night of 4/5 February. The raiding-party was to have two officers and 60 men and stretcher-bearers, to attack a salient at the junction of Guard and Desire Support trenches, take prisoners and documents, destroy machine-guns, study the state of the trenches and the way the Germans were holding the line. Stokes mortars were to be used for bombardment but no artillery was to be fired before the raid; when it began the artillery was to fire a box barrage, to isolate the objective. White suits were provided in case of snow and all means of identification were to be removed by the raiders, who were told only to give name, rank and number if captured. That night the 1st Royal Berkshire battalion was relieved and went into reserve near La Boiselle.[11]

Trenches resembling the target were found and used for five day and night rehearsals. The attack was scheduled for 3:00 a.m. on the night of 4/5 February and the party moved forward to the Miraumont dugouts at 6:00 p.m. on 2 February. The battalion commander made a reconnaissance and chose the jumping-off position. Three wooden tripods, painted black on the British side and white on the German, about 30 yd (27 m) beyond the British wire identified the centre and flanks of the raiding route. About 15 minutes before zero hour, the party stole forward in pairs, in their white camouflage and formed two waves 15 yd (14 m) apart at the tripods. Three more tripods had been placed 30–40 yd (27–37 m) further on, to help the raiders keep direction. The Stokes mortars of the 99th Trench Mortar Battery opened fire, one mortar firing "rapid" at a particular German post at zero.[15]

A minute later, the divisional artillery began the box-barrage, as the raiding party moved to within 50 yd (46 m) of the objective and lay down. When the Stokes mortars ceased fire, the party rushed the German position through three rows of barbed wire, each 2.5 ft (0.76 m) thick. The first wave moved towards the east side of the salient, thence to the western face, as the second wave jumped over the trench and ran along the parados, until they saw Germans in the trench near the apex. Several Germans were shot and the rest taken prisoner and after twenty minutes searching dugouts, the party withdrew with 51 prisoners (including two officers), having smashed a machine-gun and killed or wounded 14 German soldiers. The raiders suffered one man killed and twelve wounded.[16][lower-alpha 4]

Operations: Ancre

11 January – 14 February

British operations at the end of the Battle of the Ancre in November 1916 had captured German positions on Beaumont Hamel spur and the village of Beaucourt, before the weather stopped operations. In the early hours of 10 January, a battalion of the 7th Division attacked The Triangle and the trenches either side, including Muck Trench about 1,000 yd (910 m) east of Beaumont Hamel. The attack began after an 18-hour bombardment and a standing barrage on the objective. Due to the state of the ground, the infantry advanced in three parties, with duckboards, 20 minutes being allowed for the crossing 200–300 yd (180–270 m) of no man's land. The objectives were consolidated and a German counter-attack was broken up by British artillery fire; a prisoner later said that a second one was cancelled; the 7th Division captured 142 prisoners for 65 casualties. The success covered the right flank of the 7th Division for the main attack next day against Munich Trench, from The Triangle to the Beaumont Hamel–Serre road and a smaller attack by the 11th (Northern) Division, against German defences east of Muck Trench. The operation failed when a German dugout was not noticed and overrun in the fog; its garrison emerged behind the British as other Germans counter-attacks from the front and pushed the British back to their start line.[17]

A bombardment had been fired on the whole Fifth Army front for two days, particularly in the neighbourhood of Serre, to mislead the Germans. The attack by a brigade of the 7th Division began at 5:00 a.m., when the leading companies lined up on tapes, 200–300 yd (180–270 m) from Munich Trench. In thick fog, at 6:37 a.m., three divisional artilleries began a standing barrage on the trench and a creeping barrage started in no man's land at a rate of 100 yd (91 m) in ten minutes because the going was so bad. German resistance was slight, except at one post where the garrison held on until 8:00 a.m. The fog lifted at 10:30 a.m. and the ground was consolidated, most of it being free from observation by the Germans. V Corps took over from XIII Corps, with the 32nd and 19th (Western) divisions by 11 January, with II Corps on the south bank facing north, with the 2nd and 18th (Eastern) divisions. The 11th (Northern) Division stayed in the line, for another attack on the slope west of the Beaucourt–Puisieux road.[18]

The bunker that had gone un-noticed in the previous attack was empty but German artillery caused many casualties and then a British bombardment stopped a German counter-attack as it was forming up at 10:00 a.m.; the division was relieved on 20 January. For the rest of the month British troops sapped forward, linking the saps laterally until over the crest of Beaumont Hamel spur. The freeze continued to make movement easier, despite temperatures which fell to 15 °F (−9 °C) on 25 January. Trench foot cases declined and small attacks became easier, although digging was almost impossible. The Fifth Army continued to redeploy troops, IV Corps moving to the southern boundary of the Fourth Army, to take over ground from the French Sixth Army; I Anzac Corps on the northern Fourth Army boundary, was transferred to the Fifth Army.[18]

The 32nd Division, V Corps, advanced slightly near the Beaucourt–Puisieux road into unoccupied ground on 2 February and next day the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division tried a surprise attack on Puisieux and River trenches, which ran north from the Ancre west of Grandcourt, despite moonlight and snow on the ground. Two battalions advanced on a 1,300 yd (1,200 m) front, another battalion guarding the left flank. Neighbouring divisional artilleries co-operated and a decoy barrage was fired near Pys, on the Fourth Army boundary. Counter-battery fire began on all German batteries in range at 11:03 a.m. and seven heavy artillery groups bombarded Grandcourt, Baillescourt Farm, Beauregard Dovecote and German trench lines. The attackers lost direction but by dawn the wreckage of Puisieux and River trenches had been captured, apart from about 200 yd (180 m) in the centre and several posts on either flank. A German counter-attack on the right at 10:30 a.m., recaptured a post and at 4:00 a.m., a second attack was stopped by artillery fire. In the evening another battalion continued the attack and the Germans counter-attacked all night and recaptured several posts near the river. The last part of Puisieux Trench was captured in the morning at 11:30 a.m. at a cost of 671 British casualties and 176 German prisoners taken. Grandcourt, on the south bank of the Ancre, had been made untenable and was abandoned overnight by the Germans overnight.[19]

An attack on Baillescourt Farm was brought forward to 7 February and the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division captured the farm; south of Grandcourt, part of Folly Trench was taken by the 18th (Eastern) Division.[19] On 10 February, the 32nd Division threatened Serre with an advance of 600 yd (550 m), capturing the rest of Ten Tree Alley east of the Beaumont–Serre road. It was slightly warmer, making movement relatively easy for the battalions 97th Brigade, which attacked on a front of 1,100 yd (1,000 m). On 11 February 4:30 a.m., a German counter-attack recaptured part of the trench before being forced out. On 13 February another German attack recaptured half of the trench, before two fresh British battalions drove them out again. The advance cost the British 382 casualties, the Germans suffered heavy casualties and 210 prisoners. Each small British attack had succeeded; the captured ground secured a view over another part of the German defences and denied the defenders observation over British positions. The Fourth Army extended its front southwards to Genermont and the transfer of I Anzac Corps was completed on 15 February; the Fifth Army boundary being extended to the north of Gueudecourt.[20]

Actions of Miraumont, 17–18 February

As a preliminary to capturing the Loupart Wood line (Riegel I Stellung), Gough intended the Fifth Army to continue the process of small advances in the Ancre valley. Attacks were to be made on Hill 130, the Butte de Warlencourt, Gueudecourt, Serre and Miraumont; the Loupart Wood line would be attacked three days before the Third Army offensive at Arras. The occupation of Hill 130 would command the southern approach to Miraumont and Pys, exposing German artillery positions behind Serre to ground observation, while attacks on the north bank took ground overlooking Miraumont from the west, possibly inducing the Germans to withdraw voluntarily and uncover Serre. II Corps planned to attack on 17 February with the 2nd, 18th (Eastern) and 63rd (Royal Naval) divisions, on a 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) front. The ground was too hard to dig assembly trenches, instead the troops assembled in the open.[21]

The II Corps artillery began destructive and wire-cutting bombardments on 14 February, using ammunition with the new fuze 106 against the German wire, which proved effective, despite fog and mist making aiming and observation of the results difficult. At zero hour, four siege groups were to begin a bombardment of rear lines and machine-gun nests; four counter-battery groups were to neutralise German artillery within range of the attack.[lower-alpha 5] Artillery tactics were based on the experience of 1916, with a creeping barrage fired by half of the 18-pounders, beginning 200 yd (180 m) in front of the infantry and moving at 100 yd (91 m) in three minutes. Other 18-pounders searched and swept the area (changed aim from side to side and back and forth) from the German trenches to 250 yd (230 m) further back in succession, as the British infantry reached them. The rest of the 18-pounders fired standing barrages on each line of trenches until the creeping barrage arrived, then lifted with it. A protective barrage was formed beyond the objective according to a barrage timetable.[21]

A thaw set in on 16 February and at dawn there were dark clouds overhead and mist on the ground, which turned soft, slippery then reverted to deep mud. The speed of the creeping barrage had been set for movement over hard going and was too fast for such conditions. At 4:30 a.m. German artillery bombarded the British attack front, apparently alerted by a captured document and a deserter.[23] The British suffered many casualties as the infantry assembled but no retaliatory fire was opened, in the hope of lulling the German artillery. A subsidiary attack on the right by a battalion of the 2nd Division against Desire Support and Guard trenches, south of Pys, disappeared into the dark until 9:00 a.m., when it was reported that the attackers had been repulsed; British casualties and daylight made a resumption of the attack impossible. The effect of the failure on the right affected the operation further west by the 99th Brigade of the 2nd Division and the 54th and 53rd brigades of the 18th (Eastern) Division, which attacked the high ground from the right-hand of the two Courcelette–Miraumont roads to the Albert–Arras railway line in the Ancre valley.

The divisional boundary was west of the left-hand road from Courcelette to Miraumont, the 99th Brigade attacking on a 700 yd (640 m) front between the two sunken roads. The 54th Brigade had a front which sloped steeply to the left and included Boom Ravine (Baum Mulde), with both brigades vulnerable to flanking fire from the right. There were three objectives, the first about 600 yd (550 m) forward along the southern slope of Hill 130, the second at South Miraumont Trench another 600 yd (550 m) to the north slope of Hill 130 on the right and the railway between Grandcourt and Miraumont on the left; the final objective was the southern fringe of Petit Miraumont. The 53rd Brigade on the left flank had a wider front, much of which was also exposed to fire from the positions on the north bank due to be attacked by the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division and was to consolidate on the second objective.[24]

Each brigade attacked with two battalions, the 99th Brigade with two companies to extend the defensive flank formed on the right with the subsidiary attack and 2+1⁄2 companies following on to leapfrog through to the final objective. In the 18th (Eastern) Division area, the 54th Brigade attacked with an extra company to capture dugouts up to Boom Ravine and consolidate the first objective as the 53rd Brigade formed a defensive flank on the left. Artillery support came from the divisional artillery, army field brigades and the neighbouring 1 Anzac Corps.[lower-alpha 6] The creeping and standing barrages began at 5:45 a.m. and the infantry advanced against a sparse German artillery reply. The defenders were alert and inflicted many casualties with small-arms fire; the darkness, fog and the sea of mud slowed the advance and caused units to become disorganised. The 99th Brigade reached the first objective and established a defensive flank against German counter-attacks but the 54th Brigade found uncut wire at Grandcourt Trench and lost the barrage while looking for gaps. German troops emerged from cover and engaged the British infantry, holding them up on the right. The left-hand battalion found more gaps but had so many casualties that it was also held up. On the 53rd Brigade front, Grandcourt Trench was captured quickly but the advance was held up at Coffee Trench by more uncut wire.[26]

The Germans in Boom Ravine were engaged from the flank and three machine-guns silenced before the advance in the centre could resume and parties found their way through the wire at Coffee Trench and captured it by 6:10 a.m. Boom Ravine held out until 7:45 a.m. and the advance resumed a long way behind the creeping barrage; the line outside Petit Miraumont was attacked. On the right flank, the 99th Brigade on the right flank advanced towards the second objective, much hampered by the fog and mud. The failure to maintain the defensive flank on the right left the Germans free to rake the brigade with machine-gun fire, causing more casualties. Some 99th Brigade troops briefly got into South Miraumont Trench and but were forced back to the first objective by German counter-pressure. German reinforcements counter-attacked from Petit Miraumont and the railway bank to the west. The weapons of many British troops had clogged with mud and they fell back, the troops on the right forming a defensive flank along West Miraumont road. They were fired on from South Miraumont Trench, behind west Miraumont road, on the left flank, forcing them back to a line 100 yd (91 m) north of Boom Ravine. The attack had advanced the line 500 yd (460 m) on the right, 1,000 yd (910 m) in the centre and 800 yd (730 m) on the left. Boom Ravine was captured but the Germans had held Hill 130 and inflicted 2,207 British casualties, 118 on the 6th Brigade, 779 on the 99th Brigade, 2nd Division and 1,189 on the 18th (Eastern) Division.[26]

On the north bank, the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division attacked with a battalion of the 188th Brigade and two battalions of the 189th Brigade, to capture 700 yd (640 m) of the road north from Baillescourt Farm towards Puisieux, to gain observation over Miraumont and form a defensive flank on the left flank back to the existing front line. Two battalions attacked with a third battalion ready on the right flank to reinforce them or to co-operate with the 18th (Eastern) Division between the Ancre and the Miraumont road. On the northern flank, two infantry companies, engineers and pioneers were placed to establish the defensive flank on the left. The divisional artillery and an army field brigade with fifty-four 18-pounder field guns and eighteen 4.5-inch howitzers provided fire support, with three field batteries from the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division further north, to place a protective barrage along the northern flank. The darkness, fog and mud were as bad as on the south bank but the German defence was far less effective. The creeping barrage moved at 100 yd (91 m) in four minutes, slower than on the south bank and the Germans in a small number of strong points were quickly overcome. The objective was reached by 6:40 a.m. and the defensive flank established, the last German strong point being captured at 10:50 a.m. There was no German counter-attack until the next day, which was stopped by artillery-fire. The 63rd (Royal Naval) Division suffered 549 casualties and the three divisions took 599 prisoners.[27]

The sudden thaw, fog and unexpected darkness interfered with wire cutting, slowed the infantry, who fell behind the barrage. The apparent betrayal of the attack forewarned the German defenders, who were able to contain it and inflict considerable casualties.[27] Troops were ordered to edge forward during the next few days wherever German resistance was slight; the failure to capture Hill 130 and persistent fog, left the British overlooked and unable accurately to bombard German positions. Further deliberate attacks intended on Crest Trench were made impossible by a downpour which began on 20 February. Edging forward continued in the 2nd Division area, which had gained 100 yd (91 m) since 19 February. From 10 January to 22 February, the Germans had been pushed back 5 mi (8.0 km) on a 4 mi (6.4 km) front.[28] The Action of Miraumont forced the Germans to begin their withdrawal from the Ancre valley before the scheduled retirement to the Hindenburg Line.[29] At 2:15 a.m. on 24 February, reports arrived that the Germans had gone and by 10:00 a.m. patrols from the 2nd Australian Division on the right and the 2nd and 18th (Eastern) divisions in the centre and left, were advancing in a thick mist with no sign of German troops.[30] Further south, the German positions around Le Transloy were found abandoned on the night of 12/13 March and Australian Light Horse and infantry patrols entered Bapaume on 17 March.[31]

Operations: Somme

Minor operations

In January and February the Fourth Army began to relieve French troops south of Bouchavesnes. XV Corps took over the ground south to the Somme River on 22 January; III Corps moved south to Génermont on 13 February and IV Corps was transferred from the Fifth Army to relieve French forces south to the Amiens–Roye road. Despite the disruption of these moves, minor operations continued, to deceive the Germans that the Battle of the Somme was resuming. On 27 January, a brigade of the 29th Division attacked northwards on a 750 yd (690 m), front astride the Frégicourt–Le Transloy road, towards an objective 400 yd (370 m) away. The attack had the support of creeping and standing barrages from ninety-six 18-pounder field guns, extended on either side by the neighbouring divisions and sixteen 4.5-inch howitzers, two 6-inch and one 9.2-inch howitzer batteries. A section of 8-inch howitzers was available for the bombardment of strong points and road junctions and the XIV Corps heavy batteries were able to neutralise German artillery during the attack. The operation took the unusually large number of 368 prisoners, for 382 casualties.[32]

A 400 yd (370 m) length of Stormy Trench was attacked by part of a battalion of the 2nd Australian Division late on 1 February, which took the left-hand section and bombed down it to take the rest, before being forced out by a German counter-attack at 4:00 a.m. The Australians attacked again on the night of 4 February, with a battalion and an attached company, with more artillery support and a stock of 12,000 grenades, since the first attack had been defeated when they ran out. A German counter-attack was repulsed after a long bombing-fight, although the Australians had more casualties (350–250 men) than the earlier failed attack. On 8 February, a battalion of the 17th (Northern) Division attacked part of a trench overlooking Saillisel, after spending three weeks digging assembly trenches in the frozen ground. Artillery support was similar to that of the 29th Division attack and the objective was gained quickly, with troops wearing sandbags over their boots to grip the ice. German counter-attacks failed but a greater number of casualties was inflicted after the attack, mainly by German artillery fire over the next two days. British attacks on the Fourth Army front ceased until the end of the month.[33]

The 8th Division conducted an attack on 4 March, which was prepared in great detail. Preparation had fallen into disuse in 1915, due to the dilution of skill and experience caused by the losses of 1914 and the rapid expansion of the army from 1915 to 1916.[34] In February, instructions were issued from the divisional headquarters covering communications, supply dumps, equipment, arms and ammunition to be carried by each soldier, the proportion of the attacking units to be left out of battle, medical arrangements, substitute commanders, liaison, wire-cutting and bombardment arrangements of SOS signals for artillery and machine-gun barrages, gas bombardment, smoke screens and measures to deal with stragglers and prisoners. The instructions went into great detail, stipulating that officers were to dress the same as their men, precautions were to be taken to stop machine-gun barrages falling on friendly troops, the positions of observers and the calculation of safety distances. Signals to open fire were a green very light, a red and white rocket, a yellow and black flag or Morse SOS by signal lamp, at which the machine-gunners were to fire for ten minutes. The morale of British as well as German units had suffered and special arrangements were made to collect "stragglers" at brigade and divisional posts, where soldiers names were to be taken, before being rearmed and equipped with items taken from wounded troops in Advanced Dressing Stations.[35]

The Épine de Malassise (Malassise Spine), hog's-back (a long narrow-rested ridge with slopes of nearly equal steepness) overlooks Bouchavesnes and the Moislains valley towards Nurlu. The objective of the attack was to capture the north end of the spine to deny the Germans observation of the valley behind Bouchavesnes and the view towards Rancourt. Two trenches on a front of 1,200 yd (1,100 m) were to be captured to the east and north-east of the village, which would also threaten the German positions north of Péronne, potentially hastening any German withdrawal on the Somme front. The 25th Brigade on the right was to attack with one battalion on a 300 yd (270 m) front and the 24th Brigade on the left was to attack with two battalions over an 800 yd (730 m) front; mopping-up parties and carriers were provided by other battalions. No destructive bombardment on the objectives was fired, as it was intended to occupy them but wire cutting and the bombardment of strongpoints, trench junctions and machine-gun nests took place for several days before the attack. Machine-gun barrages to be fired over the heads of the attacking troops and on the flanks were arranged, with the divisional machine-gun unit and that of the 40th Division.[36]

The freezing weather prevented the digging of assembly trenches again and the leading waves had to form up on lines of tapes, ready for the attack at 5:15 a.m. The troops were given chewing gum to stop them coughing; a slight mist aided concealment and a slight frost improved the going. The barrage began on time and after five minutes began to lift. The first objective at Pallas Trench was taken with few losses. At the junction of the attacking brigades, a small section which held out was quickly captured before reverse-fire by the Germans there could stop the troops who had passed beyond. Pallas Trench was occupied by moppers-up and the attacking troops reached the second objective at Fritz Trench on the right and Pallas Support Trench on the left. Some troops advanced so swiftly that they went beyond the objective to Fritz Trench and captured a machine-gun before returning.[36]

The defenders repulsed the attack at the Triangle; when it was eventually captured troops on the flanks were needed to reinforce the attackers, who had incurred many casualties. British arrangements for holding captured ground worked well and a German battalion in a wood near Moislains preparing to counter-attack was dispersed by the machine-gun barrage with 400 casualties. German troops overrun by the attack were captured or killed by mopping-up parties following the advanced troops. During the day, the Germans nearby counter-attacked five times over open ground but they were easily visible from Fritz Trench and repulsed by small-arms fire. German attempts to bomb their way back up communication trenches were also defeated. German artillery-fire on the captured area, on the former no man's land and around Bouchavesnes caused considerably more casualties when two communications trenches were being dug to link the new positions with the old British front line.[37]

German bombardments continued during the night of 4/5 March before a counter-attack on the British right flank, which captured a trench block and about 100 yd (91 m) of Fritz Trench to the north, before a local British attack recovered the lost ground. German artillery-fire continued all day and at 7:30 p.m., German infantry seen massing on the right flank were dispersed by SOS artillery and machine-gun barrages before they could attack; German bombardments continued on 6 March, before slowly diminishing. The operation cost the British 1,137 casualties; 217 German prisoners and seven machine-guns were captured and "exceedingly heavy" German casualties inflicted, according to surveys of the vicinity after the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung). The new positions menaced the German defences at Péronne and further south, which with the capture of Irles by the Fifth Army on 10 March, forced the Germans to commence their retirement towards the Siegfriedstellung two weeks early.[38]

Air operations

.jpg.webp)

The Royal Flying Corps undertook a considerable tactical reorganisation after the battle of the Somme, according to the principles incorporated in documents published between November 1916 and April 1917.[39][lower-alpha 7] During the winter on the Somme 1916–1917, the new organisation proved effective. On the few days of good flying weather, much air fighting took place, as German aircraft began to patrol the front line; of 27 British aircraft shot down in December 1916, 17 aeroplanes were lost on the British side of the front line. German aircraft were most active on the Arras front to the north of the Somme, where Jasta 11 was based.[41]

By January 1917 the German aerial resurgence had been contained by formation flying and the dispatch of Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) pilots from Dunkirk flying the Sopwith Pup, which had a comparable performance to the best German aircraft; both sides also began to conduct routine night operations. Distant reconnaissance continued, despite the danger of interception by superior German aircraft, to observe the German fortification building behind the Somme and Arras fronts, which had been detected in November 1916. On 25 February, reconnaissance crews brought news of numerous fires burning behind the German front line, all the way back to the new fortifications. Next day 18 Squadron reported the formidable nature of the new line and the strengthening of German intermediate lines on the Somme front.[41]

Aftermath

German withdrawals on the Ancre

British attacks in January 1917 had taken place against exhausted German troops holding poor defensive positions, left over from the fighting in 1916; some troops had low morale and showed an unusual willingness to surrender. The army group commander Generalfeldmarschall Crown Prince Rupprecht, advocated a withdrawal to the Siegfriedstellung on 28 January, which General Erich Ludendorff refused, changed his mind and authorised on 4 February and the first "Alberich Tag" was set for 9 February. The British attacks in the Actions of Miraumont from 17 to 18 February and anticipation of further attacks, led Rupprecht on 18 March to order a withdrawal of about 3 mi (4.8 km) on a 15 mi (24 km) front from Essarts to Le Transloy of the 1st Army to the Riegel I Stellung, on 22 February.[42] The withdrawal caused some surprise to the British, despite the interception of wireless messages from 20 to 21 February.[43]

The second German withdrawal took place on 11 March, during a preparatory British bombardment; the British did not notice until the night of 12 March. Patrols found the line empty between Bapaume and Achiet-le-Petit and strongly held on either flank. A British attack on Bucquoy at the north end of Riegel I Stellung on the night of 13/14 March was a costly failure. German withdrawals on the Ancre spread south, beginning with a retirement from the salient around St Pierre Vaast Wood. On 16 March, the main German withdrawal to the Siegfriedstellung began.[43] The retirement was conducted in a slow and deliberate manner, through a series of defensive lines over 25 mi (40 km) at the deepest point, behind rear-guards, local counter-attacks and the demolitions of the Alberich plan.[44]

Analysis

The British Official History and numerous other publications distinguish between local withdrawals, forced on the German 1st Army by British attacks on the Ancre in the new year against determined opposition and the main German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung) which was mainly protected by rear-guards, other historians treat them as part of the same operation.[45] British operations on the Ancre took place during a period of considerable change in British methods and equipment. Over the winter, an increasing flow of weapons and munitions from British industry and overseas suppliers, was used to increase the number of Lewis guns to 16 per battalion, a scale of one per platoon.[46] A new infantry training manual that standardised the structure, equipment and methods of the infantry platoon was prepared over the winter and was published as SS 143 in February 1917. The division was re-organised, according to the system given in SS 135 ("Instructions for the Training of Platoons for Offensive Action") of December 1916. The 8th Division attack at Bouchavesnes on 4 March, took place after the changes to the infantry platoon had been implemented, which provided them with the means to fight forward, in the absence of artillery support and under local command, as part of a much more structured all-arms attack than had been achieved in 1916.[47]

The advance was still conducted in waves behind a creeping barrage, to ensure that the infantry arrived simultaneously at German trenches but the waves were composed of skirmish lines and columns of sections, often advancing in artillery formation, to allow them to deploy quickly when German resistance was encountered. Artillery formation covered a 100 yd (91 m) frontage and 30–50 yd (27–46 m) depth in a lozenge shape, the rifle section forward with the rifle bombers and bombing sections arranged behind on either side. The platoon headquarters followed, slightly in front of the Lewis gun section. Artillery was much more plentiful and efficient in 1917 and had been equipped with a local communications network, which led a corresponding devolution of authority and a much quicker response to changing circumstances. The success of the attack led to a set of the orders and instructions being sent to the US Command and Staff College to serve as models.[48]

The organisation of artillery was revised according to a War Office pamphlet of January 1917, "Artillery Notes No.4–Artillery in Offensive Operations", which put the artillery of each corps under one commander, established a Counter Bombardment Staff Officer, provided for the artillery of several divisions to be co-ordinated and laid down that artillery matters were to be considered from the beginning when planning an attack. The uses of equipment were standardised, the 18-pounder field gun was to be mainly used for barrages, bombardment of German infantry in the open, obstructing communications close to the front line, wire cutting, destroying breastworks and preventing the repair of defences, using high explosive (H. E.), Shrapnel shell and the new smoke shells. The QF 4.5-inch howitzer was to be used for neutralising German artillery with gas shells, bombarding weaker defences, blocking communication trenches, night barrages and wire-cutting on ground where field guns could not reach. The BL 60-pounder gun was to be used for longer-range barrages and counter-battery fire, the 6-inch gun for counter-battery fire, neutralisation-fire and wire-cutting using the new No. 106 Fuze. The larger howitzers were reserved for counter-battery fire against well-protected German artillery and the larger guns for long-range fire against targets like road junctions, bridges and headquarters.[49]

Co-ordination of artillery was improved by using more telephone exchanges, which put artillery observers in touch with more batteries. Observing stations were built to report to artillery headquarters at corps headquarters on the progress of infantry and a corps signals officer was appointed to oversee artillery communication, which had become much more elaborate. Visual signalling was used as a substitute for line communications and some short-range [7,000 yd (4.0 mi; 6.4 km)] wireless transmitters were introduced. Weighing 101 lb (46 kg), needing four men to carry and considerable time to set up, the wireless proved of limited value. Artillery boards came into use, which had blank sheets with a 1:10,000 scale grid in place of maps, datum shooting was used to check gun accuracy from two to three times a day and better calibration drills and meteor (weather) telegrams were announced. The tactical role of artillery was defined as the overpowering of enemy artillery, the killing or incapacitating of enemy infantry and the destruction of defences and other obstacles to movement. Barbed-wire was the most difficult obstruction to tackle and 1,800–2,400 yd (1.0–1.4 mi; 1.6–2.2 km) was the best range for cutting it with 18-pounder field guns (with regular calibration and stable gun platforms), conditions which were not always met.[50]

A barrage drill was devised to prevent the opponent from manning his parapets and installing machine-guns in time to meet the assault. Attacks were supported by creeping barrages, standing barrages covered an area for a period of time, back barrages were to cover exploitation by searching (back and forth) and sweeping (side to side), to catch troops and reinforcements while moving. One 18-pounder for each 15 yd (14 m) of barrage line was specified, to be decided at the corps artillery headquarters and creeping barrages should move at 100 yd (91 m) a minute and stop 300 yd (270 m) beyond an objective, to allow the infantry room to consolidate. Surplus guns were added the barrage, to be ready to engage unforeseen targets. A limit of four shells per minute was imposed on 18-pounder guns, to retard barrel wear (before 1917 lack of ammunition had made barrel-wear a minor problem) and use of smoke shell was recommended, despite the small quantity available. Ammunition expenditure rates were laid down for each type of gun and howitzer, with 200 shells per gun per day for the 18-pounder.[50]

The experience of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1916, had shown that single-engine fighters with superior performance could operate in pairs but where the aircraft were of inferior performance, formation flying was essential, even though fighting in the air split formations. By flying in formations made up of permanent sub-units of from two to thee aircraft, British squadrons gained the benefit of concentration and a measure of flexibility, the formations being made up of three sub-units; extra formations could be added to be mutually supporting. Tactics were left to individual discretion but freelancing became less common. By the end of the Somme battle, it had become usual for reconnaissance aircraft to operate in formation with escorts and for bomber formations to have a close escort of six F.E.2bs and a distant escort of six single-seat fighters. The revival of the German Air Service (Die Fligertruppen) and formation of the Luftstreitkräfte in October 1916, led in October to the British using wireless interception stations (Compass Stations) quickly to locate aircraft operating over the British front, as part of a system. Trained observers gleaned information on German aircraft movements from wireless signals or ground observation and communicated the bearing from interception stations by wireless to wing headquarters or telephoned squadrons direct. Aircraft on patrol were directed to busy areas of the front by ground signals, although no attempt was made to control the interception of individual aircraft from the ground.[51]

Alberich Bewegung (Alberich Manoeuvre)

The severe cold ended in March and thaws turned the roads behind the British front into mudslides. German demolitions provided means to repair roads once the British advance began but traffic carrying the material did as much damage as the weather. Attempts to move artillery forward encountered severe delays. Ammunition had been moved forward in preference to road material in February and the German withdrawals in the Ancre valley, left the guns out of range.[52] During the winter, many British draught horses had died of cold, overwork and lack of food, leaving the Fifth Army 14,000 horses short. The line of the road from Serre to Bucquoy, through Puisieux was almost impossible to trace but the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division and 19th (Western) Division, on the flanks of the 7th Division of V Corps, fought its way into Puisieux on 27 February and began skirmishing towards Bucquoy by 2 March.[53]

The 18th (Eastern) Division surrounded and swiftly captured Irles on 10 March and the 7th and 46th (North Midland) Division were ordered to occupy Bucquoy on 14 March, after air reconnaissance reported it almost empty. Protests were made by Major-General George Barrow, the 7th Division commander, Brigadier-General Hanway Cumming, commander of the 91st Brigade, Major-General William Thwaites of the 46th (North Midland) Division and Brigadier-General john Campbell, the commander of the 137th Brigade, after patrols had reported that the village was protected by many machine-guns and three belts of wire, despite two days of wire-cutting bombardments. The V Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Edward Fanshawe, insisted that the attack go ahead and agreed only a delay until moonrise at 1:00 a.m. The artillery bombardment was fired from 10:00 p.m.–10:30 p.m. alerting the German defenders, who repulsed the attack. The 91st Brigade lost 262 casualties and the 137th Brigade 312 casualties, the Germans withdrew two days later.[53][54]

On 19 March, I Anzac Corps was ordered to advance on Lagnicourt and Noreuil, under the impression that the fires foreshadowed a retirement beyond the Hindenburg Line. The 2nd Australian Division and the 5th Australian Division were past Bapaume, towards Beaumetz and Morchies and followed up the withdrawal of the 26th Reserve Division from Vaulx-Vraucourt.[55] Beaumetz was captured by 22 March and then lost during the night to a German counter-attack, which led the Australians to plan the capture of Doignies and Louveral with the 15th Brigade in daylight, without artillery or flank support. The plan was countermanded by the divisional commander, Major-General Talbot Hobbs, as soon as he heard of it and Brigadier-General Elliott was nearly sacked. The 7th Division commander, after the costly repulse at Bucquoy, delayed his 1,200 yd (1,100 m) advance on Ecoust and Croisilles, to liaise with the 58th (2/1st London) Division to the north-west.[56] Gough ordered the attack on Croisilles to begin without delay but the advance was stopped by the Germans at a belt of uncut wire on the outskirts of the village. Gough sacked Barrow and left his replacement, Major-General T. Shoubridge, in no doubt about the need for haste. The Hindenburg Line was unfinished on the Fifth Army front and a rapid advance through the German rearguards in the outpost villages, might make a British attack possible before the Germans were able to make the line "impregnable".[56] The village eventually fell on 2 April, during a larger co-ordinated attack on a 10 mi (16 km) front, by the I Anzac Corps on the right flank and the 7th and 21st divisions of V Corps on the left, after four days of bombardment and wire-cutting.[57]

The British official historian, Cyril Falls, described the great difficulty in moving over devastated ground beyond the British front line. Carrying supplies and equipment over roads behind the original British front line was even worse, due to over-use, repeated freezing and thaws, the destruction of the roads beyond no man's land and demolitions behind the German front line. The British command was reluctant to risk unsupported forces against a German counter-attack and the evidence from the Fifth Army front, that hasty attacks became impractical once the Germans had begun the main retirement (16–20 March), led to a steady pursuit instead.[58] The Australian official historian, Charles Bean, wrote that the advanced troops of I Anzac Corps had gone out on a limb, which had led to the reverse at Noreuil on 20 March, after instructions from the Fifth Army headquarters to press forward to the Hindenburg Line, were misinterpreted.[59]

Advances were delayed as roads were rebuilt and more pack transport was organised, to carry supplies forward for larger attacks on the German outpost villages. In 1998, Walker contrasted the local withdrawals on the Ancre valley, where hasty but well organised British attacks had sometimes succeeded in ousting German garrisons. The determined German defence of outpost villages, after the rapid and scheduled part of the German retirement over 2–3 days, gained time to complete the remodelling of the Hindenburg Line, from south of Arras to St Quentin. The Fifth Army was far enough advanced by 8 April, to assist the Third Army attack at Arras on 9 April, having captured the outpost villages of Doignies, Louveral, Noreuil, Longatte, Ecoust St Mein, Croisilles and Hénin sur Cojeul on 2 April.[60] On the right flank, Hermies, Demicourt and Boursies were captured by the 1st Australian Division on 8 April, after the Fourth Army took Havrincourt Wood on the right flank.[61]

Notes

- 2nd Guard Reserve Division, 14th Bavarian Division, 33rd Division, 18th Division, 17th Division and the 1st Guard Reserve Division from north to south.[2]

- IV Corps: 51st (Highland) Division, 61st (2nd South Midland) Division and the 11th (Northern) Division, XIII Corps held the north bank with 7th Division, 3rd Division and 31st Division. II Corps with the 2nd Division, 18th (Eastern) Division, 63rd (Royal Naval) Division and V Corps with the 19th (Western) Division and 32nd Division was in reserve.[4]

- Second Lieutenant T. W. Doke, taken prisoner taken on 11 January, told the Germans that they hardly needed to snatch prisoners because so many Germans were deserting. Doke claimed that three officers and 37 men had deserted in one day and on 10 January, fifteen more Germans deserted and it appeared that the division opposite was collapsing. None of the Germans admitted to desertion, claiming instead that they had blundered into the British lines by mistake.[8]

- A raid on the night of 8/9 February was postponed until 10 February. Several Germans were killed by the raiders as they retreated and more men in four dugouts were killed with hand-grenades when they refused to surrender. Seven prisoners were taken and the party of 36 lost three killed, seven wounded and three missing. The Germans retaliated on 12 February, when about 70 men raided the area between posts 9 and 10 and took seven prisoners. Five dead Germans were found between the posts but machine-gun fire prevented no man's land being searched.[16]

- Siege groups II, XXV, XXXVI and XL were heavy artillery groups with ten 6-inch howitzer, five 8-inch howitzer, two 9.2-inch howitzer batteries and two 15-inch howitzers. Counter-battery fire came from the IX, X, XIV and LV Heavy artillery groups, with ten 60-pounder gun, two 6-inch gun, one 4.7-inch howitzer, two 6-inch howitzer, two 8-inch howitzer, two 9.2-inch howitzer, two 12-inch howitzer batteries and two 15-inch howitzers.[22]

- A hundred and fifty 18-pounder field guns, forty-two 4.5-inch howitzers plus four field artillery and two howitzer batteries of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division on the south bank, firing from thirty minutes after zero hour, to assist the 53rd Brigade, although the curve of the ground made aiming difficult.[25]

- Notes on Aeroplane Fighting in Single-Seater Scouts (November 1916), Fighting in the Air (March 1917) and Aerial Cooperation During the Artillery Bombardment and the Infantry Attack (April 1917).[40]

Footnotes

- Boraston 1920, pp. 63–65.

- Falls 1992, p. 64.

- Falls 1992, pp. 64–67.

- Falls 1992, pp. 66–67.

- Falls 1992, pp. 127–130.

- Edmonds & Wynne 2010, pp. 59–61.

- Falls 1992, pp. 65–66.

- Sheldon 2017, p. 189.

- Bewsher 1921, pp. 128–131.

- Bewsher 1921, pp. 131–135.

- Wyrall 2002, pp. 361–362.

- Atkinson 2009, pp. 324–329.

- Atkinson 2009, pp. 324–332.

- Atkinson 2009, pp. 330–332.

- Wyrall 2002, pp. 361–365.

- Wyrall 2002, pp. 362–365.

- Falls 1992, pp. 66–68.

- Falls 1992, pp. 68–70.

- Falls 1992, pp. 70–72.

- Falls 1992, pp. 68–74.

- Falls 1992, pp. 73–76.

- Falls 1992, p. 76.

- Falls 1992, p. 82.

- Falls 1992, pp. 77–78.

- Falls 1992, p. 79.

- Falls 1992, pp. 78–81.

- Falls 1992, pp. 81–82.

- Nicholson 1962, p. 241.

- Nichols 2004, p. 153.

- Wyrall 2002, pp. 374–375.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 458–459.

- Falls 1992, pp. 82–84.

- Falls 1992, pp. 84–86.

- Thomas 2010, p. 233.

- Thomas 2010, pp. 236–237.

- Bax & Boraston 2001, pp. 101–103.

- Bax & Boraston 2001, pp. 103–106.

- Sheffield 2011, p. 211.

- Jones 2002, p. 317.

- Jones 2002, pp. 389–412.

- Jones 2002, pp. 302–306.

- Bean 1982, p. 60.

- Falls 1992, pp. 94–110.

- Philpott 2009, p. 460.

- Sheffield 2011, p. 211; Falls 1992, p. 93; Philpott 2009, p. 456.

- Falls 1992, p. 11.

- Sheffield 2011, pp. 209–211.

- Thomas 2010, pp. 245, 252.

- Farndale 1986, p. 158.

- Farndale 1986, p. 159.

- Jones 2002, pp. 317–320.

- Walker 2000, p. 55.

- Falls 1992, p. 109.

- Walker 2000, pp. 54–55.

- Walker 2000, pp. 54–59.

- Walker 2000, pp. 60–61.

- Atkinson 2009, pp. 354–369.

- Falls 1992, pp. 162–167.

- Bean 1982, pp. 153–154.

- Walker 2000, p. 61.

- Falls 1992, pp. 168–169.

References

Books

- Atkinson, C. T. (2009) [1927]. The Seventh Division 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-1-84342-119-1.

- Bax, C. E. O.; Boraston, J. H. (2001) [1926]. Eighth Division in War 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: Medici Society. ISBN 978-1-897632-67-3.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1982) [1933]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. IV (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-7022-1710-4. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Bewsher, F. W. (1921). The History of the 51st (Highland) Division, 1914–1918 (online ed.). Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. OCLC 3499483. Retrieved 23 March 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- Boraston, J. H. (1920) [1919]. Sir Douglas Haig's Despatches (2nd ed.). London: Dent. OCLC 633614212.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (2010) [1940]. Military Operations France & Belgium 1917: Appendices. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-84574-733-6.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-180-0.

- Farndale, M. (1986). Western Front 1914–18. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. London: Royal Artillery Institution. ISBN 978-1-870114-00-4.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1931]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. Vol. III (pbk. facs. repr. Imperial War Museum department of Printed Books and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-414-7. Retrieved 23 September 2021 – via Archive Foundation.

- Nichols, G. H. F. (2004) [1922]. The 18th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Blackwood. ISBN 978-1-84342-866-4.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). The Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 59609928. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Sheldon, J. (2017). Fighting the Somme: German Challenges, Dilemmas & Solutions. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-47388-199-0.

- Walker, J. (2000) [1998]. The Blood Tub, General Gough and the Battle of Bullecourt, 1917 (Spellmount ed.). Charlottesville, Va: Howell Press. ISBN 978-1-86227-022-0.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1921]. The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. Vol. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. OCLC 752705537. Retrieved 23 March 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

Theses

- Thomas, A. M. (2010). British 8th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914–18 (PhD). Birmingham: Birmingham University. OCLC 690665118. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

Further reading

- Foerster, Wolfgang, ed. (2012) [1938]. Die Kriegsführung im Herbst 1916 und im Winter 1916/17: vom Wechsel in der Obersten Heeresleitung bis zum Entschluß zum Rückzug in die Siegfried-Stellung [The War in the Autumn of 1916 and the Winter of 1916–17, the Change in the Supreme Command to the Decision to Retreat to the Siegfried Position]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Vol. XI (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. OCLC 257730011. Retrieved 18 April 2016 – via Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich.

- Foerster, Wolfgang, ed. (2012) [1939]. Die Kriegsführung im Frühjahr 1917. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Vol. XII (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. OCLC 248903245. Retrieved 18 April 2016 – via Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich.

- Hussey, A. H.; Inman, D. S. (2002) [1921]. The Fifth Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press repr. ed.). London: Nisbet. ISBN 978-1-84342-267-9. Retrieved 26 March 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- Pidgeon, Trevor (2017) [1998]. Boom Ravine: Somme. Battleground Europe (2nd ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-0-85052-612-7.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 26 March 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- Taylor, C. (2014). I Wish They'd Killed You in a Decent Show: The Bloody Fighting for Croisilles, Fontaine-les-Croisilles and the Hindenburg Line, March 1917 to August 1918. Brighton: Reveille Press. ISBN 978-1-908336-72-9.

- Whitton, F. E. (2004) [1926]. History of the 40th Division (Naval & Military Press ed.). Aldershot: Gale and Polden. ISBN 978-1-84342-870-1. Retrieved 13 October 2014. url leads to orig ed.