Theatre of Italy

The theatre of Italy originates from the Middle Ages, with its background dating back to the times of the ancient Greek colonies of Magna Graecia, in Southern Italy, the theatre of the Italic peoples and the theatre of ancient Rome. It can therefore be assumed that there were two main lines of which the ancient Italian theatre developed in the Middle Ages. The first, consisting of the dramatization of Catholic liturgies and of which more documentation is retained, and the second, formed by pagan forms of spectacle such as the staging for city festivals, the court preparations of the jesters and the songs of the troubadours.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| People |

| Traditions |

| Literature |

Renaissance humanism was also a turning point for the Italian theatre. The recovery of the ancient texts, both comedies and tragedies, and texts referring to the art of the theatre such as Aristotle's Poetics, also gave a turning point to representational art, which re-enacted the Plautian characters and the heroes of Seneca's tragedies, but also building new texts in the vernacular.

The Commedia dell'arte (17th century) was, at first, an exclusively Italian phenomenon. Commedia dell'arte spread throughout Europe, but it underwent a clear decline in 18th century.

During the second half of the 19th century, the romantic tragedy gave way to the Teatro verista. At the beginning of the 20th century, the influences of the historical avant-gardes made themselves felt: Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism. The second post-war period was characterized by the Teatro di rivista.

Background

Ancient Greek theater in Magna Graecia

The Sicilian Greek colonists in Magna Graecia, but also from Campania and Apulia, also brought theatrical art from their motherland.[1] The Greek Theatre of Syracuse, the Greek Theatre of Segesta, the Greek Theatre of Tindari, the Greek Theatre of Hippana, the Greek Theatre of Akrai, the Greek Theatre of Monte Jato, the Greek Theatre of Morgantina and the most famous Greek Theater of Taormina, amply demonstrate this.

Only fragments of original dramaturgical works are left, but the tragedies of the three great giants Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides and the comedies of Aristophanes are known.[2]

Some famous playwrights in the Greek language came directly from Magna Graecia. Others, such as Aeschylus and Epicharmus, worked for a long time in Sicily. Epicharmus can be considered Syracusan in all respects, having worked all his life with the tyrants of Syracuse. His comedy preceded that of the more famous Aristophanes by staging the gods for the first time in comedy. While Aeschylus, after a long stay in the Sicilian colonies, died in Sicily in the colony of Gela in 456 BC. Epicarmus and Phormis, both of 6th century BC, are the basis, for Aristotle, of the invention of the Greek comedy, as he says in his book on Poetics:[3]

As for the composition of the stories (Epicharmus and Phormis) it came in the beginning from Sicily

— Aristotle, Poetics

Other native dramatic authors of Magna Graecia, in addition to the Syracusan Formides mentioned, are Achaeus of Syracuse, Apollodorus of Gela, Philemon of Syracuse and his son Philemon the younger. From Calabria, precisely from the colony of Thurii, came the playwright Alexis. While Rhinthon, although Sicilian from Syracuse, worked almost exclusively for the colony of Taranto.[4]

Italic theater

The Italic peoples such as the Etruscans had already developed forms of theatrical literature.[5] The legend, also reported by Livy, speaks of a pestilence that had struck Rome, at the beginning, and the request for Etruscan historians. The Roman historian thus refused the filiation from the Greek theater before contacts with Magna Graecia and its theatrical traditions. There are no architectural and artistic testimonies of the Etruscan theater.[5] A very late source, such as the historian Varro, mentions the name of a certain Volnio who wrote tragedies in the Etruscan language.

Even the Samnites had original representational forms that had a lot of influence on Roman dramaturgy such as the Atellan Farce comedies, and some architectural testimonies such as the theater of Pietrabbondante in Molise, and that of Nocera Superiore on which the Romans built their own.[6]

Ancient Roman theater

With the conquest of Magna Graecia, the Romans came into contact with Greek culture, therefore also with the theater. Probably already, after the wars with the Samnites, the Romans had already known representative art, but also the Samnite representations, in turn, were influenced by the Greek ones.[7] The apex of the expression of the Roman theater was reached, for the comedy by Livius Andronicus, a native of Magna Graecia, probably Taranto, who was the link between the Greek and Latin theater.[8] Less famous author, but always a bridge between the Greeks and the Italian colonies and the Latins was Gnaeus Naevius from Campania, who lived at the time of the Punic Wars. Nevio tried to create a politicized theater, in the Athenian style of Aristophanes, but the poet's arrows too often struck famous gens such as that of the Scipios. For this reason the playwright was exiled to Utica where he died poor.[9] On the contrary, Ennius, also from Magna Graecia, used the theater to incense the Roman noble families.

The major followers of Latin comedy, still linked to Greek comedy, were Plautus and Terence who Romanized the texts of Greek comedies. Plautus is considered a more popular poet, as is Caecilius Statius, while Terence is considered more of a purist as well as Lucius Afranius considered the Latin Menander. In the tragic field, Seneca was the greatest among the Latins, but the philosopher never reached the heights of Greek examples. While a tragic of Latin imprint was Ennius, whose works were highly appreciated by the aristocracy.

There were many passages that led from the primitive Latin comedy to the great playwrights mentioned above. The Roman theater was similar to the Greek one, although there were differences,[10] both from the architectural point of view and from the clothing of the actors. These used masks and coats like the Greek ones. Even the Roman theaters had a cavea and a fixed tripartite scenography. Many scenographies have remained as evidence of this typology, both in the colonies as in Leptis Magna, today in Libya, which almost integrates it. In Italy it is rarer to find in similar conditions. In Rome, the comedy was probably more welcome than the tragedy, also given the originality of the texts that freed itself from the Greek tradition with themes closer to everyday reality.[11]

The true popular expression of the Roman theater can be identified in the representations called Atellane. These were satirical comedies of Osco-Samnite imprint recited in the local dialect, and then spread to the rest of the Empire, in Rome itself in the first place.[11]

Origins of Italian theatre

The origins of Italian theatre are a source of debate among scholars, as they are not yet clear and traceable with certain sources. Since the end of the theatre of ancient Rome, which partly coincided with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, mimes and comedies were still performed. Alongside this pagan form of representation, mostly performed by tropes and wandering actors of which there are no direct written sources, the theatre was reborn, in medieval times, from religious functions and from the dramatization of some tropes of which the most famous and ancient is the short Quem quaeritis? from the 10th century, still in Latin.

It can therefore be assumed that there were two main lines on which the ancient Italian theatre developed. The first, consisting of the dramatization of Catholic liturgies and of which more documentation is retained, and the second, formed by pagan forms of spectacle such as the staging for city festivals,[12] the court preparations of the jesters and the songs of the troubadours.[13]

Medieval theatre

The theatre historian therefore based his research method, in the field of the origins of Italian theatre, not only on the actual study of his own subject but also combining it with ethnological and anthropological study as well as that of religious studies in a broad sense.[14][15]

The Catholic Church, which found in the dramatization of the liturgies a more than favorable welcome from the masses, as demonstrated by the development of theatrical practice on major holidays, paradoxically had a contradictory behavior towards them: if on the one hand it allowed and encouraged their diffusion, however he always deprecated its practice, because it was misleading from the principles of Catholicism.[16] The pagan spectacles suffered the same fate, where the judgments and measures taken by the religious were much harsher: still in 1215, a Constitution of the Lateran Council forbade clerics (among other things) to have contact with histrions and jugglers.[17] The strong contrast of religious authority to theatrical practice decreed a series of circumstances that differentiate medieval theatre (which still cannot be defined as "Italian" in the strict sense) from that known from Humanism onwards, much closer to the modern concept of theatrical representation. For over ten centuries there was never the construction of a theatrical building, unlike what happened in ancient Greece and imperial Rome.

Despite the numerous restrictions, the vernacular dramaturgy develops due to the trouvères and jesters, who sing, lute in hand, the most disparate topics: from love driven towards women to mockery towards the powerful. There is evidence in the Laurentian Rhythm of 1157 and in other more or less contemporary rhythms such as the Rhythm of Sant'Alessio, of the dramatization in verse by anonymous people in the vernacular, although the metric is still indebted to the Latin versification. More famous is the XIII century Rosa fresca aulentissima, by Cielo d'Alcamo, a real jester mime destined for stage representation, which does not spare double entenders and overly licentious jokes towards the fair sex in verses.

Even more articulated were the texts of Ruggieri Apuliese, a jester of the 13th century of which there is little or no news, mostly discordant, but in which a sardonic ability can be traced to parody and dramatize the events, enclosed in his gab and serventesi. During the 13th century, however, the jester prose in the vernacular suffered a setback due to the marginalization of the events to which it was linked: representations in Curta, street performances, and more of which the chronicle does not remember.

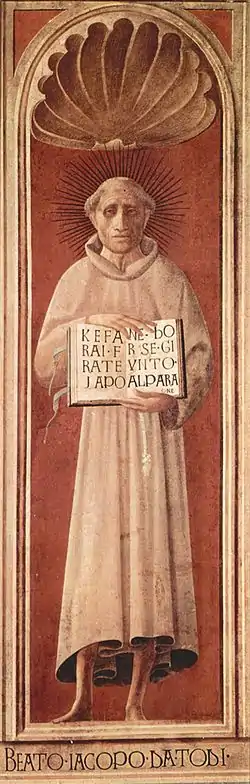

Medieval religious theatre

The lauda dramatica flourished in the same period, which later evolved into the sacred representation:[18] the lauda, derived from the popular ballad, was made up of stanzas represented first in verse, then in the form of dialogue. An example of transformation into a dialogic drama is a result of Donna de Paradiso by Jacopone da Todi, where the dialogue between John the Baptist, the Mary and Jesus is articulated on a religious topic: in it there is a fine linguistic and lexical intervention (the subdued language of the Mary and Christ compared to that of the John the Baptist) and a skilful capacity for dramatizing the event. It should be emphasized that this type of religious theatricality did not properly spread within the Church, but developed above all in Umbria following a serious plague that decimated the country, due to the Flagellant, congregations of faithful used to self-flagellation, which by virtue of their religious acts they well combined the processions of repentance with accompaniment with dramatic laudi. If they found representation in Orvieto, as in other Umbrian centers (remember the famous Corporal of Bolsena), another important epicenter of laude productions was L'Aquila,[19] where the articulation of the same was such as to require three days for a complete representation (as in the case of the anonymous Leggenna de Sancto Tomascio).

The Sacred representation, the last famous chapter of medieval religious theatre, developed from the fifteenth century in Tuscany and was fortunate also in the following centuries although it will lose the characteristic of the main protagonist of the Italian theatre. As the laude was already performed in places outside the ecclesiastical building, and was recited both in Latin and in the vernacular. Unlike the lauds, the texts are not in small numbers and bear the signature of great names, not least that of Lorenzo the Magnificent whose La rappresentazione dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo denotes a certain richness of style and complexity of dramatic interweaving.

Mario Apollonio recognizes a substantial difference, at a strictly theatrical level, between lauda and sacred representation: if the first is aimed at religious edification, the second does not hide the interest in the show or spectacle, from which a greater attention to the text - not for nothing drawn up by scholars - to the scenic artifice, to the scenographic contribution as an important support to the representation.[20]

It can therefore be admitted with certainty that, in different forms, theatrical practice remained alive and strongly connected to religious worship throughout the Italian territory: to a lesser extent, to collective events such as court parties and festivals.

Elegiac comedy

A separate chapter with respect to religious representation consists of those productions in Latin verse known as elegiac comedies (medieval Latin comedies). It is a set of Medieval Latin texts, mainly composed of the metric form of the elegiac couplet[21] and characterized, almost always, by the alternation of dialogues and narrated parts and by comic and licentious contents.

The flowering of the genus is mainly inscribed within the European season of the so-called rebirth of the 12th century and is affected by the ferment of that cultural climate that the philologist Ludwig Traube called Aetas Ovidiana. as a whole, it was a phenomenon that certainly cannot be affirmed as Italian: on the contrary, Italy was just touched by this phenomenon, in a later period, the thirteenth century: all Italian productions refer to the environment of the court and chancellery of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (the singular De Paulino et Polla by Riccardo da Venosa, and the De uxore cerdonis, attributed to Jacopo da Benevento).[22]

However, their genuine theatrical nature is not clear: it is not known, for example, if they were mere rhetorical products or rather works intended for a real staging (in this case, acting with a single voice is considered more likely);[23] not even one is able to appreciate the influence on the rise of medieval theatre in the vernacular, even if some comic elements have passed to the theatre. The small flowering of this genus enjoyed considerable success; its importance in literary history is noteworthy, due to its influence on subsequent authors in vulgar languages, in particular on medieval fabliaulistics and novellistics of which they anticipate themes and tones, and on humanistic comedy of the fifteenth century.

The scenography

Throughout the Middle Ages no theatrical building was ever built, so that it is impossible to speak of theatrical architecture. Regarding the scenography, it can be completely placed on the level of sacred representations, since jesters and buffoons, troubadours and singers did not use support elements that could help the spectator in the figuration of the story narrated. The almost nil iconographic support that has come makes a faithful reconstruction difficult, but the lists of the Brotherhood "stuff", which have come down to us, have been helpful, testifying to a wealth of furnishings not comparable to the modern conception of theatre but still of a certain thickness: the list of the Perugian brotherhood of Saint Dominic is very well known, where you can find shirts, gloves, cassocks, wigs and masks.[24]

The representations, which came out of the church in search of larger places of reception and where there was the possibility of using scenic artists certainly not welcome within consecrated walls, found a place in the churchyards first, in the squares and then even in the streets of the city, both in the form of a procession that does not. The pictorial support, which was necessary for a more complete recognition of the place represented and narrated, also became very important, although no names of artists who worked for their realization have come down to us. It must be borne in mind that there is no figure of set-up or set designer, so such works necessarily had to submit to the requests of the brotherhoods, and almost certainly carried out by untrained artists or of little fame given that the possible gain was little.

Humanism

The age of Humanism, between the 14th and 15th centuries, knows the genesis and the flowering of the so-called humanistic comedy, a phenomenon that can be considered entirely Italian. Like the elegiac comedies, these are texts in Latin, also of a licentious and paradoxical subject. Beyond the consonance of common themes (perhaps also due to their nature as literary topoi), the relationship between the two genres is not clear: certainly, humanistic comedies are more effective in updating certain themes, with a transposition on a high floor, in order to show them in their exemplary nature and use them as allusions to contemporary situations. Unlike the elegiac comedy, it is known with certainty that the humanistic comedies were intended for staging. The fruition took place in the same high-cultural and university-goliardic environment in which they were produced. In fact, as has been stated, the "linguistic-expressive operation that was the basis of these comic works [...] could only be received and appreciated in high-level cultural contexts, but also sensitive to a comedy of a goliardic matrix : university circles thus represented the natural pool of readers and spectators of humanistic theatrical writings".[25]

The importance of the humanistic comedy lies in the fact that it marks the genesis of the "profane drama", the result not of a cultural process from below, but of an invention from above, carried out by a cultured and participating urban bourgeoisie, able to grasp and elaborate the ferments of an era of great transformation and renewal.[26] Thus the foundations were laid for a process of liberation of the theatre from the religious forms of representation and from the Catholic Church, an emancipation that would then be accomplished, definitively and in a short time, without friction or conflict with the papal curia, with the Italian-language comedies of the Renaissance theatre.

Renaissance theatre

The Renaissance theatre marked the beginning of the modern theatre due to the rediscovery and study of the classics, the ancient theatrical texts were recovered and translated, which were soon staged at the court and in the curtensi halls, and then moved to real theatre. In this way the idea of theatre came close to that of today: a performance in a designated place in which the public participates.

In the late 15th century two cities were important centers for the rediscovery and renewal of theatrical art: Ferrara and Rome. The first, vital center of art in the second half of the fifteenth century, saw the staging of some of the most famous Latin works by Plautus, rigorously translated into Italian.[27] On 5 March 1508 the first comedy in Italian was performed at the court of Ferrara, La Cassaria by Ludovico Ariosto, indebted to the Terenzian model of comedy. The popes, however, saw a political instrument in the theatre: after years of opposition, the papacy finally endorsed the art of theatre, first under the spur of Pope Sixtus IV who, due to the Roman Academy of Julius Pomponius Laetus, saw the remaking of many comedies. Latinas; subsequently the contribution of Pope Alexander VI, lover of representations, allowed the diffusion of the same to many celebrations, including weddings and parties.

Another important center of the revival of modern theatre was Florence, where a classic comedy, the Andria by Terence, was staged first in 1476.[28] The Tuscan capital stood out in the 15th century for the enormous development of the Sacred representation, but soon a group of poets, starting with Agnolo Poliziano, gave their contribution to the spread of Renaissance comedy.

A figure in its own right is that of Angelo Beolco known as Il Ruzante, author of comedies in the Venetian language, actor and director supported by the patron Luigi Cornaro: although the linguistic peculiarity allowed little to spread it in the Italian context, alternating periods of celebrity and forgetfulness of the author over the centuries, he represents an example of the use of theatre as a representation of contemporary society, very often seen from the side of the countryside. Venice, in which a scenario of varied theatrical activities was operating, developed the diffusion of this art late by virtue of an amendment of 1508 by the Council of Ten, which prohibited theatrical activity. The edict was never slavishly observed, and due to these infractions the mariazo, the eclogue, the pastoral comedy, the erudite or cultured comedy developed. Venice also saw the birth of an anonymous comedy, La Venexiana, very far from the canons of erudite comedy, which reflects a licentious and brilliant as well as desecrating cross-section of the libertine aristocracy of the Serenissima. An author in his own right, also full of creative originality and tending towards the bizarre, is Andrea Calmo, a poet with six works, and who enjoyed a certain fame in his native Venice.

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, Rome became the center of a series of studies on theatrical art that allowed the development of the perspective scene and scenographic experimentation, due to the studies of Baldassare Peruzzi, painter and set designer.

Commedia dell'arte

Commedia dell'arte (lit. 'comedy of the profession')[29] was an early form of professional theatre, originating in Italy, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries.[30][31] It was formerly called "Italian comedy" in English and is also known as commedia alla maschera, commedia improvviso, and commedia dell'arte all'improvviso.[32] Characterized by masked "types", commedia was responsible for the rise of actresses such as Isabella Andreini[33] and improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios.[34][35] A commedia, such as The Tooth Puller, is both scripted and improvised.[34][36] Characters' entrances and exits are scripted. A special characteristic of commedia is the lazzo, a joke or "something foolish or witty", usually well known to the performers and to some extent a scripted routine.[36][37] Another characteristic of commedia is pantomime, which is mostly used by the character Arlecchino, now better known as Harlequin.[38]

The characters of the commedia usually represent fixed social types and stock characters, such as foolish old men, devious servants, or military officers full of false bravado.[34][39] The characters are exaggerated "real characters", such as a know-it-all doctor called Il Dottore, a greedy old man called Pantalone, or a perfect relationship like the Innamorati.[33] Many troupes were formed to perform commedia, including I Gelosi (which had actors such as Andreini and her husband Francesco Andreini),[40] Confidenti Troupe, Desioi Troupe, and Fedeli Troupe.[33][34] Commedia was often performed outside on platforms or in popular areas such as a piazza (town square).[32][34] The form of theatre originated in Italy, but travelled throughout Europe - sometimes to as far away as Moscow.[41]

The genesis of commedia may be related to carnival in Venice, where the author and actor Andrea Calmo had created the character Il Magnifico, the precursor to the vecchio (old man) Pantalone, by 1570. In the Flaminio Scala scenario, for example, Il Magnifico persists and is interchangeable with Pantalone into the 17th century. While Calmo's characters (which also included the Spanish Capitano and a dottore type) were not masked, it is uncertain at what point the characters donned the mask. However, the connection to carnival (the period between Epiphany and Ash Wednesday) would suggest that masking was a convention of carnival and was applied at some point. The tradition in Northern Italy is centred in Florence, Mantua, and Venice, where the major companies came under the protection of the various dukes. Concomitantly, a Neapolitan tradition emerged in the south and featured the prominent stage figure Pulcinella, which has been long associated with Naples and derived into various types elsewhere—most famously as the puppet character Punch (of the eponymous Punch and Judy shows) in England.

18th century

This century was a difficult period for the Italian theatre. Commedia dell'arte spread throughout Europe, but it underwent a clear decline as the dramaturgy decreased and little attention was paid to the texts it offered, compared to other works from the rest of Europe. However, the Commedia dell'arte remained an important school that lasted more than 100 years, and important authors of the Renaissance period were unable to offer a wide range of works thus being able to build the foundations for a future school.

Goldoni did not break into the theatre scene as a revolutionary but as a reformer. At first he indulged the taste of the public, still tied to the old masks. In his first comedies the presence of Pantalone, Brighella and with a great Harlequin, perhaps the last of a large caliber in Italy, like Antonio Sacco who played with the mask of Truffaldino, is constant. For this company Goldoni wrote important comedies such as The Servant of Two Masters and La putta onorata. In 1750 the Venetian lawyer wrote the manifesto text of his comedy reform: Il teatro comico.[42] In this comedy the ancient Commedia dell'arte and its Commedia riformata are compared. Carlo Goldoni used new companies from which the masks, by now too improbable in a realist theatre, disappeared, just as their jokes and jokes, often unrelated to the subject, disappeared. In his riformate comedies the plot returns to being the central point of the comedy and the most realistic characters. Francesco Albergati Capacelli, a great friend of Goldoni and his first follower, continued along this line.

Goldonism was fiercely opposed by Pietro Chiari, who preferred more romantic and still Baroque-style comedies. Later, in the critique of the Goldonian reform, Carlo Gozzi also joined the group who hindered the reform, dedicating himself to the exhumation of the ancient 17th century Commedia dell'arte, now moribund, but still vital in its academic variant: the Commedia ridicolosa which, until the end of the century continued to use the masks and characters of that of art.[43] The tragedy, in Italy, did not have the development it had had, since the previous century, in other European nations. In this case, Italy suffered from the success of the Commedia dell'arte. The path of the Enlightenment tragedy was followed by Antonio Conti, with moderate success. Aimed at the French theatre is the work of Pier Jacopo Martello who adapted the Alexandrian verse of the French to the Italian language, which was called Martellian verse. But the major theorist who pursued the path of an Italian tragedy of Greek-Aristotelian style was Gian Vincenzo Gravina. His tragedies, however, did not have the hoped-for success because they were considered unsuitable for representation. While his pupil Pietro Metastasio adapted Gravina's teachings by applying them to the lyrics of the melodrama. Other librettists such as Apostolo Zeno and Ranieri de' Calzabigi followed him on this path. The greatest tragedian of the early 18th century was Scipione Maffei who finally managed to compose an Italian tragedy worthy of the name: the Merope. In the second half of the century the figure of Vittorio Alfieri, the greatest Italian tragedian of the 18th century, dominated.[44]

19th century

During the 19th century, the Dramma romantico was born. There were important authors promoting the genre, such as Alessandro Manzoni and Silvio Pellico. In the second half of the century, the romantic tragedy gave way to the Teatro verista, which saw Giovanni Verga and Emilio Praga among the greatest exponents.[45]

The romantic drama was preceded by a period close to Neoclassicism, represented by the dramatic work of Ugo Foscolo and Ippolito Pindemonte aimed at Greek tragedy. Vittorio Alfieri himself, who spans the two centuries, can be defined, together with Vincenzo Monti, forerunner and symbol of neoclassical tragedy.[46]

The Goldonian lesson developed over the course of this century. However, it must clash with the invasion of certain French achievements of the theatre of art, already Frenchized since the previous century, such as the Comédie larmoyante which opened up to the development of the real Italian bourgeois drama. While among the 19th century heirs of Goldoni's comedy also are, among others, Giacinto Gallina, Giovanni Gherardo de Rossi and Francesco Augusto Bon.

An evolution similar to the theatrical drama takes place in the field of theatre for music. At the beginning of this century, the Melodramma romantico replaced the Neapolitan and then Venetian Opera buffa.[47] A work close to the great medieval themes of the Risorgimento period was born. There are several librettists who support the musicians by building new types of epic narration for music. From Felice Romani, librettist of the early 19th century for the works of Vincenzo Bellini, up to Arrigo Boito and Francesco Maria Piave, who with the librettos for Giuseppe Verdi opened the Risorgimento period of Italian musical theatre. Boito was also one of the few who combined dramatic talent with musical talent. His opera Mefistofele, with music and libretto by the author, has a historical character, and is an important step in the evolution of the Italian theatre.[48]

Even in this century, however, the legacy, now several hundred years old, of the Commedia dell'arte remained in the dialectal theatre that continued to stage masks. The dialect theatre quietly bypassed the 18th century and continued in the staging of its comedies. Among the most important authors of this popular genre were Luigi Del Buono, who in Florence also continued in the 19th century to stage the character of Stenterello. Another 19th century author of dialect theatre was Pulcinella by Antonio Petito. Semi-illiterate Petito was the one who had taken over the monopoly of the Neapolitan theatre. His canvases had been modernized and Pulcinella had also become a political symbol. Adversary of the Absolutism of the end of the 18th century, the Pulcinella of the 19th century appeared up to the middle of the pro-Bourbon century.[49] However, the Neapolitan character had had its maximum splendor just under the reign of the Bourbons. In a Piedmontese Italy, the central role of Naples ended and its mask remained in the shade, now limited to a few Pulcinellesque theatres such as the Teatro San Carlino. Still in the context of the Neapolitan dialect theatre, it was the playwright Eduardo Scarpetta who established himself as the heir of the Petito in the post-unification decades. He was also the initiator of a dynasty that dominated the Neapolitan theatre scene for decades and the creator of Felice Sciosciammocca's mask; the work that most stands out in its prolific production is Miseria e nobiltà, whose fame among the last generations is also due to the film transposition of 1954 with Totò in the leading role.[50]

20th century

The first half of the century

Important playwrights were born during the 20th century, laying the foundations for the modern Italian theatre. The genius of Luigi Pirandello stands out above all, considered the "father of modern theatre".[51] With the Sicilian author, the Dramma psicologico was born, essentially characterized by the introspective aspect. Another great exponent of the 20th century dramaturgical theatre was Eduardo De Filippo. He, son of the aforementioned Eduardo Scarpetta, managed to restore the dialect within the theatrical work, eliminating the widespread conception of the past that defined the dialectal work as a second level work. With Eduardo de Filippo, the Teatro popolare was born.[52]

At the beginning of the century, the influences of the historical avant-gardes made themselves felt: Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism. Especially futurism tried to change the idea of modern theatre by adapting it to new ideas. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti took an interest in writing the various Futurist Manifests on his new idea of theatre. Together with Bruno Corra he created what was called synthetic theatre.[53] Later the Futurists formed a company, directed by Rodolfo De Angelis, which was called the Teatro della sorpresa. The presence of a scenographer like Enrico Prampolini shifted the attention more to the very modern scenographies than to the often disappointing acting. Another character who attended the theatre in this period, without notable success compared to other literary and poetic productions, was Gabriele D'Annunzio. Of him there are some tragedies of a classical context, close to the Liberty style characteristic of the whole production of the warrior-poet.

At the same time, the Teatro grottesco was born, and it was an almost entirely Italian phenomenon.[57] Other frequenters of this genre include Massimo Bontempelli, Luigi Antonelli, Enrico Cavacchioli, Luigi Chiarelli, Pier Maria Rosso di San Secondo and Pirandello himself in his first plays.

In the period of Fascism the theatre was held in great esteem. The theatre during the fascist regime was a means of political propaganda like cinema, the popular spectacle par excellence.[58] Giovanni Gentile drew up a manifesto of support for the regime of Italian intellectuals. Among the signatories some important figures of the theatre of the period: Luigi Pirandello, Salvatore di Giacomo, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Gabriele D'Annunzio. In 1925 the philosopher Benedetto Croce contrasted his Manifesto of the anti-fascist intellectuals, signed, among others, by the playwrights Roberto Bracco and Sem Benelli. During this period the two directors of the Bragaglia family were important: Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia and Anton Giulio Bragaglia who joined the more experimental productions of the period, later moved on to the cinema.

The second post-war period was characterized by the Teatro di rivista. This was already present previously with great actor-authors such as Ettore Petrolini.[59] From the magazine, actors such as Erminio Macario and Totò imposed themselves. Then large companies such as that of Dario Niccodemi and actors of the level of Eleonora Duse, Ruggero Ruggeri, Memo Benassi and Sergio Tofano were also important. Equally important was the contribution of great directors in post-war Italian theatre such as Giorgio Strehler, Luchino Visconti and Luca Ronconi. An interesting experiment was that of Dario Fo, who was greatly influenced by Bertolt Brecht's epic and political theatre, but at the same time he returned to the Italian theatre the centrality of the pure actor in ruzantesque terms with his opera Mistero Buffo which with the grammelot gave the theatre of fools and storytellers of the Middle Ages.[60]

The second half of the century

Carmelo Bene's theatre was more linked to experimentalism. The Apulian actor-playwright also tried to bring acting back to the center of attention, reworking the texts of the past, from William Shakespeare to Alfred de Musset, but also Alessandro Manzoni and Vladimir Mayakovsky. The experience of the Lombard playwright Giovanni Testori also deserves to be mentioned, for the breadth of his commitment - he was a writer, director, impresario -, the multiformity of the genres practiced, linguistic experimentalism:[61] he worked extensively with the actor Franco Branciaroli and together they profoundly influenced the post-war Milanese theatre.

1959 was the year of the debut in Rome of three central figures of the new Italian scene. In addition to Carmelo Bene (actor with Alberto Ruggiero), Claudio Remondi and Carlo Quartucci (with him Leo de Berardinis makes his debut): there is a real revolution, where the text is no longer to be served, to be staged, but the opportunity, the pretext for an operation that finds its reason directly on the stage, (La Scrittura scenica[62]). At the end of the 1960s, the Nuovo teatro[63] was strongly affected by the climate of cultural renewal of Western society, it contaminated with the other arts and the hypotheses of the avant-garde of the beginning of the century. With Mario Ricci, then with Giancarlo Nanni, both coming from painting, a second season will take the name of Teatro immagine,[64] continued by Giuliano Vasilicò, Memè Perlini, the Patagruppo, Pippo Di Marca, Silvio Benedetto and Alida Giardina with their Autonomous Theatre of Rome.[65] A theatre was often based in 'cellars', alternative spaces, among all the Beat '72 theatre in Rome, by Ulisse Benedetti and Simone Carella. In the second part of the 70s it was the third avant-garde, baptized by the dean of critics specialized Giuseppe Bartolucci, Postavanguardia,[66] a theatre characterized by a copious use of technology (amplifications, images, films), and the marginality of the text, with groups such as Il Carrozzone (later Magazzini Criminali), La Gaia Scienza, Falso Movimento, Studio Theatre of Caserta, Dal Bosco-Varesco.

Experimentalism at the end of the century brings new frontiers of theatrical art, delivered in Italy to new companies such as the Magazzini Criminali, the Krypton and Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio, but also companies that frequent a more classic theatre such as the company of the Teatro dell'Elfo by Gabriele Salvatores. The Italian theatre of the end of the century also made use of the work of the author-actor Paolo Poli. Vittorio Gassman, Giorgio Albertazzi and Enrico Maria Salerno are to be remembered among the great word actors of the 20th century. In the theatre field, important monologists such as Marco Paolini and Ascanio Celestini have recently established themselves, authors of a narrative theatre based on in-depth research work.

21st century

Subsequently, important monologists such as Marco Paolini and Ascanio Celestini established themselves in the theatrical field. Authors of narrative theatre based on in-depth research are authors and monologists such as Alessandro Bergonzoni.[67]

In the early 2010s, from the experience of permanent theatres and from the attempt to reorganize public funding towards those bodies that present direct administration of theatres and dramaturgical production,[68] the Italian government decided to reform the category, with the institution in 2014 of the Italian National Theatres and the Italian Theatres of significant cultural interest.[69][70][71][72]

Main theatres

The Teatro di San Carlo in Naples is the oldest continuously active venue for public opera in the world, opening in 1737, decades before both the Milan's La Scala and Venice's La Fenice theatres.[73] Other noteworthy Italian theaters are Teatro Regio of Turin, Teatro Olimpico of Vicenza, Teatro Petruzzelli of Bari, Teatro Regio of Parma, Teatro della Pergola of Florence, Teatro dell'Opera of Rome and Greek Theatre of Syracuse.[74]

The Real Teatro di San Carlo ("Royal Theatre of Saint Charles"), as originally named by the Bourbon monarchy but today known simply as the Teatro (di) San Carlo, is an opera house in Naples, Italy, connected to the Royal Palace and adjacent to the Piazza del Plebiscito. The opera season runs from late January to May, with the ballet season taking place from April to early June. The house once had a seating capacity of 3,285,[75] but has now been reduced to 1,386 seats.[76] Given its size, structure and antiquity, it was the model for theatres that were later built in Europe. Commissioned by the Bourbon King Charles III of Naples (Carlo III in Italian), Charles wanted to endow Naples with a new and larger theatre to replace the old, dilapidated, and too-small Teatro San Bartolomeo of 1621, which had served the city well, especially after Scarlatti had moved there in 1682 and had begun to create an important opera centre which existed well into the 1700s.[77] Thus, the San Carlo was inaugurated on 4 November 1737, the king's name day, with the performance of the opera Domenico Sarro's Achille in Sciro, which was based on the 1736 libretto by Metastasio which had been set to music that year by Antonio Caldara. As was customary, the role of Achilles was played by a woman, Vittoria Tesi, called "Moretta"; the opera also featured soprano Anna Peruzzi, called "the Parrucchierina" and tenor Angelo Amorevoli. Sarro also conducted the orchestra in two ballets as intermezzi, created by Gaetano Grossatesta, with scenes designed by Pietro Righini.[73] The first seasons highlighted the royal preference for dance numbers, and featured among the performers famous castrati.

La Scala, abbreviation in Italian of the official name Teatro alla Scala, is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the Nuovo Regio Ducale Teatro alla Scala (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performance was Antonio Salieri's Europa riconosciuta. La Scala's season opens on 7 December, Saint Ambrose's Day, the feast day of Milan's patron saint. All performances must end before midnight, and long operas start earlier in the evening when necessary. The Museo Teatrale alla Scala (La Scala Theatre Museum), accessible from the theatre's foyer and a part of the house, contains a collection of paintings, drafts, statues, costumes, and other documents regarding La Scala's and opera history in general. La Scala also hosts the Accademia d'Arti e Mestieri dello Spettacolo (Academy for the Performing Arts). Its goal is to train a new generation of young musicians, technical staff, and dancers (at the Scuola di Ballo del Teatro alla Scala, one of the Academy's divisions). Above the boxes, La Scala has a gallery—called the loggione—where the less wealthy can watch the performances. The gallery is typically crowded with the most critical opera aficionados, known as the loggionisti, who can be ecstatic or merciless towards singers' perceived successes or failures.[78] For their failures, artists receive a "baptism of fire" from these aficionados, and fiascos are long remembered. For example, in 2006, tenor Roberto Alagna left the stage after being booed during a performance of Aida, forcing his understudy, Antonello Palombi, to quickly replace him mid-scene without time to change into a costume. Alagna did not return to the production.[79]

La Fenice (The Phoenix") is an opera house in Venice, Italy. It is one of "the most famous and renowned landmarks in the history of Italian theatre"[80] and in the history of opera as a whole. Especially in the 19th century, La Fenice became the site of many famous operatic premieres at which the works of several of the four major bel canto era composers – Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi – were performed. Its name reflects its role in permitting an opera company to "rise from the ashes" despite losing the use of three theatres to fire, the first in 1774 after the city's leading house was destroyed and rebuilt but not opened until 1792; the second fire came in 1836, but rebuilding was completed within a year. However, the third fire was the result of arson. It destroyed the house in 1996 leaving only the exterior walls, but it was rebuilt and re-opened in November 2004. In order to celebrate this event the tradition of the Venice New Year's Concert started.

Museums

The Museo Teatrale alla Scala is a theatrical museum and library attached to the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, Italy. Although it has a particular focus on the history of opera and of that opera house, its scope extends to Italian theatrical history in general, and includes displays relating, for example, to the commedia dell'arte and to the famous stage actress Eleonora Duse.[81] The museum, which is adjacent to the opera house in the Piazza della Scala, was opened on 8 March 1913[82] and was based on a large private collection which had been purchased at auction two years earlier, with funds raised both from government and private sources.

References

- "Storia del Teatro nelle città d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "Il teatro" (in Italian). Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "Aristotele - Origini della commedia" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Rintóne" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Storia del teatro: lo spazio scenico in Toscana" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "La fertile terra di Nuceria Alfaterna" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "IL TEATRO DA CRETA A PIETRABBONDANTE" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- "Teatro Latino" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- "Nèvio, Gneo" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- "Differenze tra teatro greco e romano" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- "IL TEATRO ROMANO" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Festivities that are still pagan, such as the grape harvest, and mostly take place in small towns.

- Of this second root Dario Fo he speaks of a true alternative culture to the official one: although widespread as an idea, some scholars such as Giovanni Antonucci do not agree in considering it as such. In this regard, see Antonucci, Giovanni (1995). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. pp. 10–14. ISBN 978-8838241604.

- Among the first to adopt an attitude of transversal analysis in the study of the theatre is Mario Apollonio, a theatrical historian to with a different approach from the school of Benedetto Croce, who saw in the theatre the supremacy of written word and in its effect on the spectator an interest sociological. Apollonius focuses on the spoken and acted word, thus including in the analysis of the theatrical phenomenon a completely different meaning: interdisciplinary, which also had to grasp the weapons necessary to face and understand the subject in other fields of study.

- The same concept can be found in Antonucci, Giovanni (1995). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. p. 11. ISBN 978-8838241604.

- Some historians also point out that the Church needed to impose itself as the religion of the Empire, repressing paganism and the forms of cultural expression that derived from it: among these, theatrical practice. See Attisani, Antonio (1989). Breve storia del teatro (in Italian). BCM. p. 60.

- Antonucci, Giovanni (1995). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. p. 12. ISBN 978-8838241604.

- Here too the opinions differ: if some (such as Giovanni Antonucci) see in the sacred representation an evolution of the Umbrian-Abruzzese lauda dramatica, others (see the works and studies of Paola Ventrone) recognize original outcomes and diversified experiences.

- "Il teatro medievale abruzzese e la Sacra Rappresentazione" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Apollonio, Mario (2003). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). BUR. pp. 183 and following. ISBN 978-8817106580.

- Le Muse (in Italian). Vol. IV. De Agostini. 1965. p. 325.

- Bertini, Ferruccio (1984). "Il «De Uxore cerdonis», commedia latina del XIII secolo". Schede medievali (in Italian). Vol. 6–7. pp. 9–18.

- Radcliff-Umstead, Douglas (1969). The Birth of Modern Comedy in Renaissance Italy. p. xviii. ISBN 978-0226702056.

- Apollonio, Mario (2003). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). BUR. p. 186. ISBN 978-8817106580.

- Rosso, Paolo. Teatro e rappresentazioni goliardiche. In: Mantovani, Dario. (2021) Almum Studium Papiense. Storia dell'Università di Pavia (In Italian). Vol. I, tome I. p. 667

- Perosa, Alessandro (1965). Teatro umanistico (in Italian). Nuova Accademia. pp. 10–11.[ISBN unspecified]

- Antonucci, Giovanni (1995). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. p. 18. ISBN 978-8838241604.

- Antonucci, Giovanni (1995). Storia del teatro italiano (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. p. 21. ISBN 978-8838241604.

- Theatre of Italy at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Lea, Kathleen (1962). Italian Popular Comedy: A Study In The Commedia Dell'Arte, 1560–1620 With Special Reference to the English State. New York: Russell & Russell INC. p. 3.[ISBN unspecified]

- Wilson, Matthew R. "A History of Commedia dell'arte". Faction of Fools. Faction of Fools. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia Dell'Arte An Actor's Handbook. London and New York: Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-415-04769-2.

- Ducharte, Pierre Louis (1966). The Italian Comedy: The Improvisation Scenarios Lives Attributes Portraits and Masks of the Illustrious Characters of the Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Dover Publication. p. 17. ISBN 978-0486216799.

- Chaffee, Judith; Crick, Olly (2015). The Routledge Companion to Commedia Dell'Arte. London and New York: Rutledge Taylor and Francis Group. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-74506-2.

- "Faction Of Fools".

- Grantham, Barry (2000). Playing Commedia A Training Guide to Commedia Techniques. United Kingdom: Heinemann Drama. pp. 3, 6–7. ISBN 978-0-325-00346-7.

- Gordon, Mel (1983). Lazzi: The Comic Routine of the Commedia dell'Arte. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-933826-69-4.

- Broadbent, R.J. (1901). A History Of Pantomime. New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 62.

- "Faction of Fools | A History of Commedia dell'Arte". www.factionoffools.org. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Maurice, Sand (1915). The History of the Harlequinade. New York: Benjamin Bloom, Inc. p. 135.[ISBN unspecified]

- Nicoll, Allardyce (1963). The World of Harlequin: A Critical Study of the Commedia dell'Arte. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 9.[ISBN unspecified]

- "GOLDONI, Carlo" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- "Le commedie vogliono essere ridicolose" (in Italian). Biblioteca Casanatense. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- "Alfieri, Vittorio" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- "Teatro" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- "MONTI, Vincenzo" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "L'Ottocento" (in Italian). Vivi italiano. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "BOITO, Arrigo" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "THE COMMEDIA MUST GO ON" (in Italian). Ars comica. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Miseria e nobiltà" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Pirandèllo, Luigi" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "Eduardo De Filippo, ovvero una persona di famiglia" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "Futurismo" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Mitchell, Tony (1999). Dario Fo: People's Court Jester (Updated and Expanded). London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-73320-3.

- Scuderi, Antonio (2011). Dario Fo: Framing, Festival, and the Folkloric Imagination. Lanham (Md.): Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739151112.

- "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1997". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- Karp, Karol. "Il teatro italiano del grottesco: verso un indirizzo originale?" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "Il teatro di propaganda" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "Ettore Petrolini" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "ALLA CORTE DI UN GIULLARE - Omaggio a Dario Fo" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "Testori. L'autore del tumulto dell'anima" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 7 May 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "Cento storie sul filo della memoria" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Il Nuovo Teatro in Italia 1968-1975" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Giuseppe, Bartolucci (1970). Teatro corpo – Teatro immagine (in Italian). Marsilio Editori.[ISBN unspecified]

- Bargiacchi, Enzo Gualtiero; Sacchettini, Rodolfo (2017). Cento storie sul filo della memoria - Il nuovo Teatro in Italia negli anni '70 (in Italian). Titivillus. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-8872184264.

- Bartolucci, Giuseppe (2007). Testi critici 1964-1987 (in Italian). Bulzoni Editore. ISBN 978-8878702097.

- "Bergonzoni, Alessandro" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- Gallina, Mimma (2016). Ri-organizzare teatro. Produzione, distribuzione, gestione (in Italian). Franco Angeli. ISBN 978-8891718426.

- Ministerial Decree 1 July 2014

- "A cosa servono i Teatri Nazionali?" (in Italian). Ateatro. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- "Dal 2015 cancellati i teatri Stabili. E il Metastasio ha già iniziato a lottare per diventare Teatro Nazionale – VIDEO" (in Italian). TV Prato. 20 December 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- "Teatri nazionali e teatri di rilevante interesse culturale" (in Italian). Ministry of Culture. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- "The Theatre and its history". Teatro di San Carlo's official website. 23 December 2013.

- "I 10 Teatri più belli e importanti d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Gubler, Franz (2012). Great, Grand & Famous Opera Houses. Crows Nest: Arbon. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-987-28202-6.

- "Progetto di ristrutturazione del Teatro San Carlo e rifacimento impianti di sicurezza antincendio e rilevazione fumi" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Lynn, Karyl Charna (2005). Italian Opera Houses and Festivals. Scarecrow Press. p. 277. ISBN 0-8108-5359-0.

- "Cecilia Bartoli triumphs at La Scala amidst catcalls and boos". 4 December 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Wakin, Daniel J. (13 December 2006). "After La Scala Boos, a Tenor Boos Back". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Arici, Giuseppe; Romanelli, Graziano; Pugliese, Giandomenico (1997). Gran Teatro La Fenice (in German). Taschen Verlag. p. 151. ISBN 3-8228-7062-5.

- "Il Museo Teatrale alla Scala, tra oggetti e ricordi di scena" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- "Raccolta documentaria del Museo teatrale alla Scala" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 December 2022.

_-_Facade.jpg.webp)