Theudebert I

Theudebert I (French: Thibert/Théodebert) (504 – 548) was the Merovingian king of Austrasia from 533 to his death in 548. He was the son of Theuderic I and the father of Theudebald.

| Theudebert I | |

|---|---|

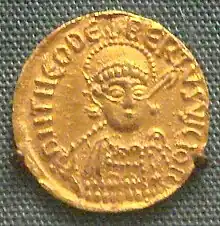

.jpg.webp) Gold solidus minted by Theudebert at Mainz around 534 | |

| King of Austrasia | |

| Reign | 534–548 |

| Predecessor | Theuderic I |

| Successor | Theudebald |

| Born | 504 |

| Died | 548 |

| Spouse | Wisigard Deuteria |

| Issue | Theudebald Berthoara |

| House | Merovingian dynasty |

| Father | Theuderic I |

Sources

Most of what we know about Theudebert comes from the Histories or History of the Franks written by Gregory of Tours in the second half of the sixth century. In addition, we have diplomatic correspondence composed at the Austrasian court (known as the Austrasian Letters), the poems of Venantius Fortunatus, an account from Procopius' work[1] and a small number of other sources.

History

During his father's reign, the young Theudebert had shown himself to be an able warrior. In 516 he defeated a Danish army under King Chlochilaich (Hygelac of Beowulf) after it had raided northern Gaul.[2] His reputation was further enhanced by a series of military campaigns in Septimania against the Visigoths.[3]

Upon his father's death, Theudebert had to fight both his uncles Childebert and Clotaire I to inherit his father's kingdom. In the end, his military prowess persuaded Childebert to abandon the dispute and adopt Theudebert as his heir.[3] Together they campaigned against Clotaire but then pursued peace after their armies were hit by a storm.

After relations between the Frankish kings had settled down, Theudebert found himself embroiled in the Gothic War started when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I attempted to subdue the Ostrogoths in Italy. Justinian saw Theudebert as an ideal ally: Austrasian lands flanked the Ostrogoths in northern Italy. The emperor paid Theudebert handsomely for his assistance, but Theudebert proved an untrustworthy ally. The Frankish armies saw the Italian conflict as an opportunity for plunder and a chance to exert their own claims to northern Italy. In the event the Byzantines were forced to fight the Franks as much as the Ostrogoths.

Theudebert seems to have revelled in his power growing on the European stage. His letters show him laying claim to a vast array of lands around Austrasia, including Byzantine lands.[4] Since the fall of the Roman Empire, the Frankish kings had always shown a certain deference to the Byzantine Emperor, but Theudebert rejected his status as an inferior leader: for example, he broke imperial custom by minting gold coins containing his own image. Hitherto former Frankish kings had respected imperial convention and circulated gold coins with the image of the emperor.[5] Not surprisingly, perhaps, the Byzantine chronicler Agathias recorded the rumour in Constantinople that the Byzantines suspected Theudebert of planning an invasion of Thrace.

In common with other Frankish rulers at the time, Theudebert took several wives as and when he wanted. As heir to his father's kingdom, he was betrothed to Wisigard, daughter of Wacho, king of the Lombards.[6] This sort of political match was rare for the Merovingian kings. Theudebert abandoned her for Deuteria, a Gallo-Roman he had met while on campaign in southern Gaul. However, his supporters were not best pleased by his treatment of Wisigard, perhaps because of the political dimension, and persuaded Theudebert to take her back. Wisigard, though, soon died, and Theudebert married again.

As well as being renowned for his military prowess, Theudebert was lauded by contemporaries for his patronage of the Gallic (French) Church. Gregory of Tours reserves special praise for him in this regard, but his piety is also mentioned by Fortunatus.

Theudebert died in the 14th year of his reign (at the end of 547 or the beginning of 548). He was killed by a bison during a hunting party.[7] Theudebald, his son by Deuteria, succeeded him. In contrast to that experienced by many Merovingian kings, Theudebald's accession was peaceful.[8]

References

- "Procopius and Britain". Vortigern Studies website. Archived from the original on 19 November 2002.

- Flierman, Robert (2017). Saxon Identities, AD 150–900. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 60.

- von Pflugk-Harttung, Julius Albert G.; Wright, John Henry (1905). The Early Middle Ages. Vol. 7. Lea Brothers.

- Epistolae Austrasicae XX

- Oman, Charles (1908). The Dark Ages, 476-918. Rivingtons. p. 117.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Effros, Bonnie (2003). Merovingian Mortuary Archaeology and the Making of the Early Middle Ages. University of California Press. p. 124.

- Agathias, Histoires, Livre

, chapter 5 in Agathias - Histoires, Introduction, traduction et notes par Pierre Maraval, ed. Les Belles Lettres, ISBN 978-2-251-33950-4 - Oman 1908, p. 118.