Thomas Woolner

Thomas Woolner RA (17 December 1825 – 7 October 1892) was an English sculptor and poet who was one of the founder-members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was the only sculptor among the original members.

Thomas Woolner | |

|---|---|

Thomas Woolner by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1852 | |

| Born | Thomas Woolner 17 December 1825 Hadleigh, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 7 October 1892 (aged 66) London, England |

| Education | Apprentice to William Behnes |

| Known for | Sculpture, illustration, and poetry |

| Notable work | Civilization, Virgilia |

| Movement | Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood |

| Spouse | Alice Gertrude Waugh (m. 1864) |

| Children | 6 |

| Family | Diana Holman-Hunt (great-niece) |

After participating in the foundation of the PRB, Woolner emigrated for a period to Australia. He returned to Britain to have a successful career as a sculptor, creating many important public works as well as memorials, tomb sculptures and narrative reliefs. He corresponded with many notable men of the day and also had some success as a poet and as an art dealer. One of his notable portrait medallions is that of William Wordsworth in St Oswald's Grasmere.

Art career

Born in Hadleigh, Suffolk, Woolner trained with the sculptor William Behnes, exhibiting work at the Royal Academy from 1843. He became friendly with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and was invited by him to join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.[1] Woolner was active in the early history of the group, emphasising the need for a more vivid form of realism in sculpture. Woolner's classical inclinations became increasingly difficult to reconcile with Pre-Raphaelite Medievalism, but his belief in close observation of nature was consistent with their aims.

Woolner's sculptures immediately after the foundation of the Brotherhood in 1848 display close attention to detail. He made his name with forceful portrait busts and medallions, but was at first unable to make a living. He was forced to emigrate to Australia in 1852 (inspiring the painting The Last of England by Ford Madox Brown), but after a year he returned to Britain, soon establishing himself as both a sculptor and art-dealer.

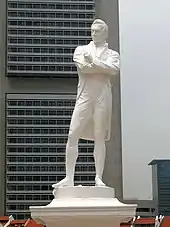

His visit to Australia nevertheless helped him to obtain commissions there and elsewhere for statues of British imperial heroes, such as Captain Cook and Sir Stamford Raffles. His bronze statue of John Robert Godley in Christchurch, New Zealand, was toppled and shattered into several pieces by the February 2011 earthquake. It has since been repaired and was re-erected in March 2015.

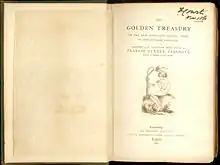

Woolner became a close friend of Francis Turner Palgrave. The two shared a house and both were known for their combative personalities. Henry Adams refers to them in The Education of Henry Adams, noting that Woolner had a "rough" personality and had to make "a supernatural effort" to be polite.[2] Woolner designed the frontispiece of a piping youth for Palgrave's famous verse anthology the Golden Treasury (1861). There was a minor scandal in 1862 when Palgrave was commissioned to write a catalogue for the 1862 International Exhibition, in which he praised Woolner and denigrated other sculptors, especially Woolner's main rival Carlo Marochetti. The well known controversialist Jacob Omnium pointed out in a series of letters to the press that the two lived together. William Holman Hunt wrote a reply supporting Woolner,[3] but Palgrave was forced to withdraw the catalogue.

His largest single commission was a programme of architectural sculptures for the Manchester Assize Courts, built in Manchester from 1859 through 1864. Woolner created a large number of statues depicting lawgivers and rulers which formed part of the building's structure. Most dramatic was a giant sculpture depicting Moses which was placed on the top, above the entrance. There were also allegorical figures of Justice and Mercy. Inside was a relief sculpture depicting the Judgement of Solomon, flanked by statues of a Drunk Woman and a Good Woman. Alfred Waterhouse, the architect, wrote, "we are all delighted with your virtuous woman, and disgusted as we ought to be with the awful example."[4] The building was bombed during World War II. Some of the sculptures were saved and incorporated into the replacement building.

Woolner made his living mainly from creating statues of famous men, but his most personal and complex works in sculpture were what he called "ideal" groups, notably Civilization (1867) and Virgilia bewailing the absence of Coriolanus (1871). These demonstrate his attempt to express the tension between the static stone and the dynamic desires of the figures represented emerging into solidity from it. Woolner also made a large number of relief sculptures for memorials. His reliefs depicting scenes from the Iliad were widely reproduced. These were intended to commemorate the classical scholarship of William Gladstone.

He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1875 and served as professor of sculpture from 1877 to 1879.

Personal life

On 6 September 1864 Woolner married Alice Gertrude Waugh. He had initially been in love with her sister, Fanny, and had previously proposed to her, but she turned him down. Fanny married Woolner's Pre-Raphaelite colleague William Holman Hunt the following year, but died in childbirth a year later. In 1874, while in Italy, Hunt married their third sister Edith, an act which Woolner considered immoral and which was defined as incest under British laws at the time. He never spoke to Hunt again.

Hunt's granddaughter Diana Holman-Hunt later claimed that before his marriage Woolner had been involved in a relationship with a lower-class girl called Amelia Henderson, who appealed to Hunt for support. Hunt arranged with Frederick Stephens to give her funds to emigrate to Australia so that she would not interfere with Woolner's wedding plans.[5]

Woolner and Alice had six children, four daughters and two sons. His eldest child, Amy, later wrote a biography of her father. His two sons Hugh (1866–1925) and Geoffrey (1867–1882) were sent to Marlborough College, where Geoffrey died at the age of 14. Hugh became a stockbroker.

Poetry and other work

Woolner was also a poet of some reputation in his day. His early poem My Beautiful Lady is a Pre-Raphaelite work, emphasising intense unresolved moments of feeling. He later expanded it into a full-length work modelled on Tennyson's narrative poetry. According to William Michael Rossetti, Coventry Patmore "praised Woolner's poems immensely, saying however that they were sometimes slightly over-passionate, and generally 'sculpturesque' in character".[6] By this, he meant that "each stanza was a separate unit".[7]

In the 1880s he wrote three long narrative works, Pygmalion, Silenus and Tiresias. These renounce Pre-Raphaelitism in favour of an often eroticised classicism. The first describes the sculptor Pygmalion's efforts to create a more realistic form of art. He battles against a group called "The Archaics". The second describes the love affair between Silenus and the nymph Syrinx. After her death at the hands of Pan, Silenus becomes an obese alcoholic, but acquires prophetic powers. A vision of the goddess Athena restores him to emotional stability. In Tiresias the blind sage recalls his long life; in a visionary pantheism, he demonstrates his power to understand the language of birds and enter into the experiences of all living things and natural forces.

Woolner was a close friend of a number of writers of the day, notably Thomas Carlyle and Alfred Tennyson. He provided the latter with the scenario for his poem "Enoch Arden".

He also corresponded with Charles Darwin, who named part of the human ear the 'Woolnerian Tip' after a feature in Woolner's sculpture Puck. Woolner had discussed the feature when Darwin had been sitting to him for a portrait. Darwin later sought his views when preparing his 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

Thomas Woolner died instantly from a stroke at the age of 66. He was buried in St Mary’s churchyard, Hendon. The kerb around his grave has a sculptor’s mallet and tools carved into it. Buried within St Mary’s Church itself is Sir Stamford Raffles, whose statue he sculpted. His wife Alice died in 1912. Their son, Hugh, travelled back to his home in New York from her funeral on the RMS Titanic. He survived the sinking of the ship.[8]

Gallery

Virgilia bewailing the absence of Coriolanus in Strawberry Hill House

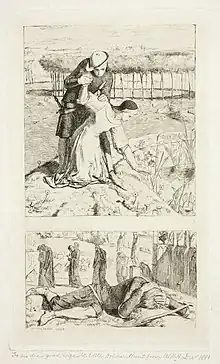

Virgilia bewailing the absence of Coriolanus in Strawberry Hill House Illustration by Holman Hunt to Woolner's "My Beautiful Lady", published in The Germ, 1850

Illustration by Holman Hunt to Woolner's "My Beautiful Lady", published in The Germ, 1850 Statue of Bishop James Fraser, Albert Square, Manchester.

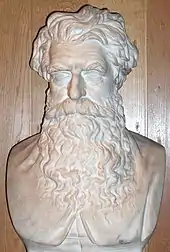

Statue of Bishop James Fraser, Albert Square, Manchester. Bust of Thomas Combe.

Bust of Thomas Combe. Replica of a statue of Sir Stamford Raffles by Woolner, erected at the spot where he first landed at Singapore. The original statue stands at the Victoria Memorial Hall. Raffles is the founder of modern Singapore.

Replica of a statue of Sir Stamford Raffles by Woolner, erected at the spot where he first landed at Singapore. The original statue stands at the Victoria Memorial Hall. Raffles is the founder of modern Singapore. Statue of Lord Palmerston, Parliament Square, London.

Statue of Lord Palmerston, Parliament Square, London. Frontispiece to Palgrave's Golden Treasury (1861).

Frontispiece to Palgrave's Golden Treasury (1861). Statue of Captain Cook, Sydney.

Statue of Captain Cook, Sydney. A Celtic warrior "attacking" the dress of the woman emblematic of civilisation in Woolner's sculpture Civilization (1867), Wallington Hall, Northumberland.

A Celtic warrior "attacking" the dress of the woman emblematic of civilisation in Woolner's sculpture Civilization (1867), Wallington Hall, Northumberland. Bust of Thomas Carlyle

Bust of Thomas Carlyle Medallion of Carlyle (1851 version)

Medallion of Carlyle (1851 version)

References

- Robinson, Michael (2007). The Pre-Raphaelites. London, England: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-84451-742-8.

- Henry Adams, Ira B. Nadel, (ed), The Education of Henry Adams, Oxford University Press, 1999, p.183.

- James H. Coombs, A Pre-Raphaelite friendship: the correspondence of William Holman Hunt and John Lucas Tupper, UMI Research Press, 1986, p.133.

- Terry Wykes, Harry Cocks, Public Sculpture of Greater Manchester, Liverpool University Press, 2004, p.76.

- Diana Holman-Hunt, My Grandfather, his Wives and Loves, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1969, p.234.

- William Michael Rossetti, ed., Pre-Raphaelite Diaries and Letters (London, 1906), p. 222.

- Lionel Stevenson, The Pre-Raphaelite Poets, University of North Carolina Press, NC, 1972, p.256.

- "The Fleecing of Woolner", Encyclopedia Titanica