Samhan

Samhan, or Three Han, is the collective name of the Byeonhan, Jinhan, and Mahan confederacies that emerged in the first century BC during the Proto–Three Kingdoms of Korea, or Samhan, period. Located in the central and southern regions of the Korean Peninsula, the Samhan confederacies eventually merged and developed into the Baekje, Gaya, and Silla kingdoms.[1] The name "Samhan" also refers to the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[2]

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Samhan |

| McCune–Reischauer | Samhan |

Sam (三) is a Sino-Korean word meaning "three" and Han is a Korean word meaning "great (one), grand, large, much, many".[3] Han was transliterated into Chinese characters 韓, 漢, 幹, or 刊, but is unrelated to the Han in Han Chinese and the Chinese kingdoms and dynasties also called Han (漢) and Han (韓). The word Han is still found in many Korean words such as Hangawi (한가위) — archaic native Korean for Chuseok (秋夕, 추석), Hangaram (한가람) — archaic native Korean for Hangang (漢江, 한강), Hanbat (한밭) — the original place name in native Korean for Daejeon (大田, 대전), hanabi (하나비) — a Joseon-era (Late Middle Korean) word for "grandfather; elderly man" (most often 할아버지 harabeoji in present-day Korean, although speakers of some dialects, especially in North Korea, may still use the form hanabi). Ma means south, Byeon means shining and Jin means east.[4]

Many historians have suggested that the word Han might have been pronounced as Gan or Kan. The Silla language had a usage of this word for king or ruler as found in the words 마립간 (麻立干; Maripgan) and 거서간 / 거슬한 (居西干 / 居瑟邯; Geoseogan / Geoseulhan). Alexander Vovin suggests this word is related to the Mongolian Khan and Manchurian Han meaning ruler, and the ultimate origin is Xiongnu and Yeniseian.[5]

The Samhan are thought to have formed around the time of the fall of Gojoseon in northern Korea in 108 BC. Kim Bu-sik's Samguk Sagi, one of the two representative history books of Korea, mentions that people of Jin Han are migrants from Gojoseon, which suggests that early Han tribes who came to Southern Korean peninsula are originally Gojoseon people. However, the state of Jin in southern Korea, which its evidence of actual existence lacks, also disappears from written records. By the 4th century, Mahan was fully absorbed into the Baekje kingdom, Jinhan into the Silla kingdom, and Byeonhan into the Gaya confederacy, which was later annexed by Silla.

Beginning in the 7th century, the name "Samhan" became synonymous with the Three Kingdoms of Korea. The "Han" in the names of the Korean Empire, Daehan Jeguk, and the Republic of Korea (South Korea), Daehan Minguk or Hanguk, are named in reference to the Three Kingdoms of Korea, not the ancient confederacies in the southern Korean Peninsula.[2][6]

Etymology

"Samhan" became a name for the Three Kingdoms of Korea beginning in the 7th century.[2]

According to the Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa, Silla implemented a national policy, "Samhan Unification" (삼한일통; 三韓一統), to integrate Baekje and Goguryeo refugees. In 1982, a memorial stone dating back to 686 was discovered in Cheongju with an inscription: "The Three Han were unified and the domain was expanded."[2] During the Later Silla period, the concepts of Samhan as the ancient confederacies and the Three Kingdoms of Korea were merged.[2] In a letter to an imperial tutor of the Tang dynasty, Choe Chiwon equated Byeonhan to Baekje, Jinhan to Silla, and Mahan to Goguryeo.[6] By the Goryeo period, Samhan became a common name to refer to all of Korea.[2] In his Ten Mandates to his descendants, Wang Geon declared that he had unified the Three Han (Samhan), referring to the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[2][6] Samhan continued to be a common name for Korea during the Joseon period and was widely referenced in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty.[2]

In China, the Three Kingdoms of Korea were collectively called Samhan since the beginning of the 7th century.[7] The use of the name Samhan to indicate the Three Kingdoms of Korea was widespread in the Tang dynasty.[8] Goguryeo was alternately called Mahan by the Tang dynasty, as evidenced by a Tang document that called Goguryeo generals "Mahan leaders" (마한추장; 馬韓酋長) in 645.[7] In 651, Emperor Gaozong of Tang sent a message to the king of Baekje referring to the Three Kingdoms of Korea as Samhan.[2] Epitaphs of the Tang dynasty, including those belonging to Baekje, Goguryeo, and Silla refugees and migrants, called the Three Kingdoms of Korea "Samhan", especially Goguryeo.[8] For example, the epitaph of Go Hyeon (고현; 高玄), a Tang dynasty general of Goguryeo origin who died in 690, calls him a "Liaodong Samhan man" (요동 삼한인; 遼東 三韓人).[7] The History of Liao equates Byeonhan to Silla, Jinhan to Buyeo, and Mahan to Goguryeo.[6]

In 1897, Gojong changed the name of Joseon to the Korean Empire, Daehan Jeguk, in reference to the Three Kingdoms of Korea. In 1919, the provisional government in exile during the Japanese occupation declared the name of Korea as the Republic of Korea, Daehan Minguk, also in reference to the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[2][6]

Three Hans

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Samhan are generally considered loose confederations of walled-town states. Each appears to have had a ruling elite, whose power was a mix of politics and shamanism. Although each state appears to have had its own ruler, there is no evidence of systematic succession.

The name of the poorly understood Jin state continued to be used in the name of the Jinhan confederacy and in the name "Byeonjin," an alternate term for Byeonhan. In addition, for some time the leader of Mahan continued to call himself the King of Jin, asserting nominal overlordship over all of the Samhan confederations.

Mahan was the largest and earliest developed of the three confederacies. It consisted of 54 minor statelets, one of which conquered or absorbed the others and became the center of the Baekje Kingdom. Mahan is usually considered to have been located in the southwest of the Korean peninsula, covering Jeolla, Chungcheong, and portions of Gyeonggi.

Jinhan consisted of 12 statelets, one of which conquered or absorbed the others and became the center of the Silla Kingdom. It is usually considered to have been located to the east of the Nakdong River valley.

Byeonhan consisted of 12 statelets, which later gave rise to the Gaya confederacy, subsequently annexed by Silla. It is usually considered to have been located in the south and west of the Nakdong River valley.

Geography

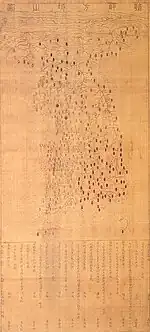

The exact locations occupied by the different Samhan confederations are disputed. It is also quite likely that their boundaries changed over time. Samguk Sagi indicates that Mahan was located in the northern region later occupied by Goguryeo, Jinhan in the region later occupied by Silla, and Byeonhan in the southwestern region later occupied by Baekje. However, the earlier Chinese Records of the Three Kingdoms places Mahan in the southwest, Jinhan in the southeast, and Byeonhan between them.

Villages were usually constructed deep in high mountain valleys, where they were relatively secure from attack. Mountain fortresses were also often constructed as places of refuge during war. The minor states which made up the federations are usually considered to have covered about as much land as a modern-day myeon, or township.

Based on historical and archeological records, river and sea routes appear to have been the primary means of long-distance transportation and trade (Yi, 2001, p. 246). It is thus not surprising that Jinhan and Byeonhan, with their coastal and river locations, became particularly prominent in international trade during this time.

Languages

One of the most prominent leader of the Han (Korean: 한; 韓) Immigration was King Jun of Gojoseon from the northern Korea, having lost the throne to Wiman, fled to the state of Jin in southern Korea around 194 - 180 BC.[9] He and his followers established Mahan which was one of the Samhan ("Three Hans"), along with Byeonhan and Jinhan. Further Han(韓) migration followed the fall of Gojoseon and establishment of the Chinese commanderies in 108 BC.

The Samhan languages (Korean: 삼한어; 三韓語) were a branch of the ancient Koreanic languages,[10][11][12][13][14][15][16] referring to the non-Buyeo Koreanic languages,[10] once spoken in the southern Korean Peninsula, which were closely related to the Buyeo languages.[14]

The Samhan languages were spoken in the Mahan, Byeonhan and Jinhan.[11][12][13] The extent of Han languages is unclear. It is generally accepted as including Sillan, and may also have included the language(s) spoken in Baekje. A number of researchers have suggested that Baekje may have been bilingual, with the ruling class speaking a Puyŏ language and the commoners speaking a Han language.[17][18][19][20]

Linguistic evidence suggests that Japonic languages (see Peninsular Japonic) were spoken in large parts of the southern Korean Peninsula, but its speakers were eventually assimilated by Koreanic-speaking peoples and the languages replaced/supplanted.[21][22][23] Evidence also suggests that Peninsular Japonic and Koreanic languages co-existed in the southern Korean Peninsula for an extended period of time and influenced each other.[24][25][26] As has been suggested for the later Korean kingdom of Baekje,[20][17][18][19] it is possible that the Samhan states were bilingual prior to the complete replacement of Peninsular Japonic by Koreanic languages.

Technology

The Samhan saw the systematic introduction of iron into the southern Korean peninsula. This was taken up with particular intensity by the Byeonhan states of the Nakdong River valley, which manufactured and exported iron armor and weapons throughout Northeast Asia.

The introduction of iron technology also facilitated growth in agriculture, as iron tools made the clearing and cultivation of land much easier. It appears that at this time the modern-day Jeolla area emerged as a center of rice production (Kim, 1974).

Relations

Until the rise of Goguryeo, the external relations of Samhan were largely limited to the Chinese commanderies located in the former territory of Gojoseon. The longest standing of these, the Lelang commandery, appear to have maintained separate diplomatic relations with each individual state rather than with the heads of the confederacies as such.

In the beginning, the relationship was a political trading system in which "tribute" was exchanged for titles or prestige gifts. Official seals identified each tribal leader's authority to trade with the commandery. However, after the fall of the Kingdom of Wei in the 3rd century, San guo zhi reports that the Lelang commandery handed out official seals freely to local commoners, no longer symbolizing political authority (Yi, 2001, p. 245).

The Chinese commanderies also supplied luxury goods and consumed local products. Later Han dynasty coins and beads are found throughout the Korean peninsula. These were exchanged for local iron or raw silk. After the 2nd century CE, as Chinese influence waned, iron ingots came into use as currency for the trade based around Jinhan and Byeonhan.

Trade relations also existed with the emergent states of Japan at this time, most commonly involving the exchange of ornamental Japanese bronzeware for Korean iron. These trade relations shifted in the 3rd century, when the Yamatai federation of Kyūshū gained monopolistic control over Japanese trade with Byeonhan.

Notes

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781107098466. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- 이기환 (30 August 2017). [이기환의 흔적의 역사]국호논쟁의 전말…대한민국이냐 고려공화국이냐. 경향신문 [The Kyunghyang Shinmun] (in Korean). Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Naver Korean dictionary

- Lu Guo-Ping. 在韓國使用的漢字語文化上的程 [A Historical Study on the Culture in Chinese Characters in Korea] (PDF) (Thesis) (in Chinese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- Vovin, Alexander (2007). "Once again on the etymology of the title qaγan". Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia. 12: 177–187.

- 이덕일 (14 August 2008). [이덕일 사랑] 대~한민국. Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "고현묘지명(高玄墓誌銘)". 한국금석문 종합영상정보시스템. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Kwon, Deok-young (2014). 唐 墓誌의 고대 한반도 삼국 명칭에 대한 검토 [An inquiry into the name of Three Kingdom(三國) inscribed on the epitaph of T'ang(唐) period]. The Journal of Korean Ancient History (in Korean). 75: 105–137. ISSN 1226-6213. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Barnes, Gina Lee (2001). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Psychology Press. pp. 29–33. ISBN 0700713239.

- Multitree: A digital library of language relationships, Bloomington, Indiana: Department of Linguistics, The LINGUIST List, Indiana University, 2014

- Kim, Nam-Kil (2003). "Korean". In Frawley, William J. (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 366–370.

- Kim, Nam-Kil (2009). "Korean". In Comrie, Bernard (ed.). The World's Major Languages (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 765–779.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press.

- Crannell, Kenneth C. (2011). Voice and Articulation. Wadsworth Company.

- Kim Wan-jin (1981), Studies on the phonological system of Korean, Ilchogak

- Horvath, Barbara M.; Vaughan, Paul (1991). Community languages: a handbook. Multilingual Matters.

- Kōno (1987), pp. 84–85.

- Kim (2009), p. 766.

- Beckwith (2004), pp. 20–21.

- Vovin (2005), p. 119.

- Janhunen, Juha (2010). "RECONSTRUCTING THE LANGUAGE MAP OF PREHISTORICAL NORTHEAST ASIA". Studia Orientalia 108 (2010).

... there are strong indications that the neighbouring Baekje state (in the southwest) was predominantly Japonic-speaking until it was linguistically Koreanized.

- Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean". Korean Linguistics. 15 (2): 222–240.

- Miyamoto, Kazuo (2022). "The emergence of 'Transeurasian' language families in Northeast Asia as viewed from archaeological evidence". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 4: e3. doi:10.1017/ehs.2021.49. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10426040. PMID 37588923. S2CID 246999130.

- Janhunen (2010), p. 294.

- Vovin (2013), pp. 222, 237.

- Unger (2009), p. 87.

References

- Kim, Jung-Bae (1974). "Characteristics of Mahan in ancient Korean society". Korea Journal. 14 (6): 4–10. Archived from the original on 2005-05-30.

- Lee, Ki-baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Translated by E.W. Wagner; E.J. Schulz (based on 1979 rev. ed.). Seoul: Ilchogak. ISBN 89-337-0204-0.

- Yi, Hyun-hae (2001). "International trade system in East Asia from the first to the fourth century". Korea Journal. 41 (4): 239–268. Archived from the original on 2005-05-30.