Tigers in Chinese culture

Tigers have been of great importance in Chinese culture since the earliest surviving records of Chinese history, with the character 虎 appearing on the Shang-era oracle bones. In prehistoric China, the Siberian, South China, and Bengal tigers were common in the northeast, southeast, and southwest respectively and tigers figures prominently in myth, astrology, Chinese poetry, painting, and other fields. Most prominently, the tiger has long been regarded as a major symbol of masculine yang energy and the king of the animals. In modern China, it generally represents power, fearlessness, and wrath.

| Tiger | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Hu | |||||||||

| Chinese | 虎 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | tiger | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Laohu | |||||||||

| Chinese | 老虎 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | old tiger venerable tiger | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Myth

The ancient Chinese believed tigers could live for a thousand years, turning white after living five centuries. Despite actually being an Old Chinese phonetic transcription of Central Asian names, the word for amber—properly 琥珀—was sometimes miswritten and misunderstood as 虎魄, "the tiger's soul".[1]

After the advent of the theory of Five Elements, some Chinese myths arose about five differently colored tigers who balanced the energy of the universe: a black tiger governing water and the winter, a verdant tiger governing earth and the spring, a red tiger governing fire and the summer, a white tiger governing metal and autumn, and a yellow tiger ruling the others.[2]

The victims of tigers were sometimes thought to become changs, undead slaves bound to lure other victims who took their place as changs in turn.[3]

Religion

In Han Chinese culture, the tiger is an important figure in Taoism and Chinese folk religion. It has long been regarded as a major symbol of masculine yang energy. The tiger was originally paired and contrasted with the dragon in Chinese myth, literature, art, and martial arts to represent the yin-yang as well as the dualities of earth and water, west and east, matter and spirit, although by the late imperial era the dragon was instead taken to represent yang and paired with the phoenix as the symbol of feminine yin instead. In Chinese antiquity, the Queen Mother of the West Xiwangmu was sometimes depicted as having a tiger tail. Presently, Zhang Daoling and the wealth god Zhao Gongming are frequently depicted riding tigers. In some areas, the birthday of the White Tiger is held to be in the second month of the lunisolar calendar or its rough solar equivalent March 6th. Some temples erect tiger effigies, and women observe it by placing paper images of tigers in their homes to ward off rats, snakes, and quarrels. On the Dragon Boat Festival, an old tradition that is still sometimes observed is drawing the figure of a 王 (see below) on the foreheads of children in arsenic realgar to protect them from snakebite and other summer ailments. In Chinese antiquity, small tiger amulets were worn for protection. Even today, in some areas, babies are given colorfully embroidered tiger shoes, tiger charms are used to ward off disease and evil, and "tiger claw" (虎爪, hǔzhǎo) amulets are used to instill the courage of a tiger and dispel fear.

The traditional religion of the Yi minority in Yunnan includes prominent tiger worship, including tiger totems and the idea that a tiger was responsible for the origin of the world. Some groups worship the tiger as part of Dongbei folk religion. Similarly, tigers were worshipped or considered to possess divine aspects in the religions of the Longshan culture of ancient Shandong, the Shu Kingdom of ancient Sichuan, and the Tungus of the Northeast.

Astrology

The White Tiger is one of the four cardinal symbols of Chinese astrology and traditional astronomy, representing autumn and the west.[4] It roughly corresponds with the prominent constellation of Orion that dominates the autumn and winter night sky.

Some myths credited the star Dubhe (α Ursae Majoris) with giving birth to the first tiger.

Separately, the Year of the Tiger is the 3rd year of the duodecennial Chinese zodiac, based on the stars imagined to be in opposition to the Jovian cycle.

Geography

Many Chinese place names reference tigers, most prominently the Taoist religious center Mount Longhu ("Dragon-&-Tiger Mountain") in Jiangxi. The Taiwanese islands Hujing and Menghu are named for tigers ("Tiger Well" and "Fierce Tiger").

Fengshui, the Chinese system of geomancy, requires that burial sites be somewhat higher on the right side to allow the White Tiger to guard it.

Government

The ancient Chinese states who fought under the nominal supervision of the Zhou during the Spring and Autumn Period used tiger tallies as symbols of their generals' royal authorization and as guides to the ruthlessness and strength the generals were intended to show. They continued to be used as late as the 7th-century Sui, sometimes divided into two interlocking pieces to ensure commanders in the field only responded to authentic supervision.

A yellow tiger was used as the primary emblem of the flag of the short-lived Republic of Formosa declared by the Chinese residents on Taiwan in 1895 after the treaty ending the First Sino-Japanese War yielded control of the island from the Qing Empire to the Empire of Japan. The Japanese army overcame formal resistance within the year.

Art

_Heritage_Museum_Sha_Tin_Hong_Kong.jpg.webp)

Representations of tigers have been discovered dating at least as far back as 5000 BC, during the neolithic cultures that preceded China proper. The Four Symbols—the tiger, dragon, phoenix, and turtle—are extremely commonly depicted in Chinese art, even outside mythic and astrological contexts. For their supposed ability to scare off evil (cf. the legend of the nian), tiger images were also once popular Chinese New Year decorations, although they are now more commonly restricted to use during the Years of the Tiger. Similarly, tigers were long carved onto Chinese tombs and monuments as guardians against thieves.

The bi'an was considered a tigerlike dragon, one of the Dragon King's nine sons. Effigies of its tiger head were placed prominently above the entrances of Chinese prisons as warnings and guardians.

Traditional Chinese chamber pot urinals were traditionally shaped and decorated to resemble crouching tigers, causing them to become known as huzis.

Music

The wooden yu used to mark the end of pieces of music in yayue, the ritual music of ancient China's Zhou dynasty, was shaped like a tiger. It was played by using a bamboo whisk to strike the tiger's head and to run across the serrated back's 27 teeth, which sometimes aligned with the stripes of the instrument's tiger decoration. Although the Classic of Music that instructed creation and use of the yayue instruments is almost entirely lost and aspects of modern construction and performance are guesswork or replacement, a few temples—including the main Taiwan Confucian Temple—still use reconstructed yu for Confucian ceremonies. It is also used in Korean court ritual in the form of the eo.

Medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine prominently advocates the use of many parts of the tiger as remedies to a wide variety of diseases and disorders. Western interest principally focuses on the use of tiger penis as a supposed aphrodesiac and erectile dysfunction curative,[5] although there is a much larger trade in bones as a pain killer and general tonic, believed to prolong life. As of 2007, there was no scientific evidence confirming any of these beliefs.[6]

Although Mao Zedong campaigned against "sympathy for the downtrodden" as a bourgeois sentiment,[7] declared tigers enemies of man,[8] and ordered extermination campaigns in 1959 during the Great Leap Forward,[8] prompting many Mainland Chinese to consider caring about animals counter-revolutionary[9] and causing China's wild tiger population to plummet between 1950 and 1980, tigers are now specially protected against international trade by the CITES treaty China joined in 1981 and protected against domestic trade by laws in place since 1993,[10] with some tiger poaching offenses subject to the death penalty. On 15 March 2010, the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies (世界中醫藥學會聯合會, 世界中医药学会联合会, Shìjiè zhōngyīyào xuéhuì liánhéhuì) issued a statement that the "political issue" of tiger conservation made it "necessary for the traditional Chinese medicine industry to support the conservation of endangered species, including tigers".[11] However, industrial-scale tiger farming has become widespread as a substitute,[12] to the point that other CITES signatories were obliged to restate their opposition to any move towards resuming international trade in tigers or their parts in 2007[6] after Chinese diplomats approached India about loosening restrictions with regard to farmed products.[13] Despite a notional ban on TCM products involving tiger components and other tiger consumption until 2018,[14] China's Forestry and Grassland Administration issued permits to at least 150 companies during the ban authorizing them to sell tigers who died in captivity.[15] It was considered an "open secret" that those with connections to the tiger farms, zoos, and wildlife parks are able to access tiger parts when needed.[14]

Cuisine

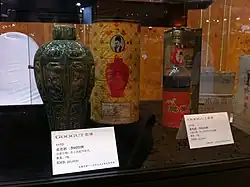

Han Chinese cuisine, particularly Cantonese cuisine, generally has fewer dietary restrictions than most other cultures. In part because of lingering belief in its TCM efficacy, tiger meat is illegal but highly prized, selling for thousands of RMB per jin on the black market.[15] In 2015, one farm in Heilongjiang Province in Northeastern China was found to be storing 200 carcasses in refrigeration, hoping for an end to the official ban.[14] Tiger bone wine—rice wine or baijiu supposedly soaked for years with tiger bones—can sell for as much as 100,000 RMB per bottle openly on internet shopping sites.[15] Tiger penis is typically consumed as a ginger-infused soup.[15]

Folklore

In Chinese folklore, the tiger has been considered the king of the animals since at least the Han-era Shuowen Jiezi,[16] with stripes over its forehead frequently redrawn to form the character for king (王).[4][17] In folk tales, tigers generally enact divine judgment, killing evil men and protecting the good in accordance with the will of Heaven.[18] Some successfully contest the tigers, while other times resistance is useless, a tiger bring lovers together,[19] or one rewards kind or virtuous behavior.[20] In the official History of the Jin, the biography of the Taoist hermit Guo Wen (郭文, Guō Wén, fl. c. 322) quotes him as explaining how he was able to live unharmed in his mountain retreats with the words "If a person does not think of harming a beast, the beast does not harm them".[21] In one story, a father threatens a Taoist immortal so that he can wear his transformative tiger skin to visit home; using it to travel quickly in the form of a tiger, he eats his son while imagining him no different from a pig.[19] In another, a man condemned by Heaven to live as a tiger for eating a magic fish attempts to bring prey to his family to provide for them but, not recognizing him, they kill him.[22] One Taoist legend concerns two brothers who protect humanity by capturing demons and throwing them to tigers.

A common theme is that tigers do not harm those who do not show fear in their presence, although Chinese writers frequently treat enormous fear of the tiger as completely natural and the protective "fearlessness" they describe is not bravery but the good fortune to be asleep or to not notice a tiger that is passing by. This is taken as an aspect of divine fate.[23]

Modern culture

In modern China, the tiger is thought to represent power, fearlessness, and wrath. Numerous chengyu—traditional Chinese idioms—reference them,[24][25] most famously Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (臥虎藏龍, "one with hidden talents"). Those born in the Year of the Tiger are popularly considered to be especially strong, brave, stubborn, and sympathetic. Able generals are called "tiger generals" and brave soldiers "tiger warriors". Tiger images frequently decorate children's clothing, decorations, toys, and tops.

See also

- Four Asian Tigers, all within the Sinosphere

- Fu (tally)

References

Citations

- "Chinese Tiger in Painting and Its Symbolic Meaning". CNArtGallery at the Chinese Paintings Blog (Artisoo Paintings – Bring Chinese culture to the world). 13 March 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "What Do Tiger Tattoos Symbolize in Eastern Cultures?". China Houston. 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- Hammond (1996), p. 199.

- Cooper (1992), pp. 226–27.

- Harding (2006).

- Weirum (2007).

- Tobias (2012).

- Matthiessen (2000), p. 185.

- Levitt (2013).

- Nowell (2007).

- WWF (2010).

- Abbott et al. (2011).

- Smithsonian (2007).

- Qian (2018).

- Adelstein (2017).

- Hammond (1996), p. 194.

- "Tigers In Culture And Folklore". Amelia Meyer (Tigers – The most majestic cats in the world). 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Hammond, Charles E. (1996), "The Righteous Tiger and the Grateful Lion", Monumenta Serica, vol. 44, Taylor & Francis, pp. 191–211, JSTOR 40727087.

- Hammond (1996), p. 192.

- Hammond (1996), pp. 194–198.

- Hammond (1996), p. 195.

- Hammond (1996), p. 198.

- Hammond (1996), pp. 203–204.

- Ceinos Arcones, Pedro (2022), "12 Chinese Idioms Related to the Tiger", Ethnic China.

- Liu, Hatty (28 July 2020), "Choice Chengyu: Idioms that Roar", The World of Chinese.

Bibliography

- "China Pushes for Tiger Meat on the Menu", Smithsonian Magazine, Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 21 May 2007.

- "Chinese Medicine Societies Reject Tiger Bones ahead of CITES", Official site, Gland: World Wildlife Fund, 12 March 2010.

- Abbott, Brant; et al. (2011), "Can Domestication of Wildlife Lead to Conservation? The Economics of Tiger Farming in China" (PDF), Ecological Economics (PDF), vol. 70, pp. 721–728, doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.11.006

- Adelstein, Jake (14 April 2017), "Why Do Chinese Oligarchs Secretly Love Illegal Tiger Meat", Daily Beast, New York: IAC.

- Cooper, J.C. (1992), Symbolic and Mythological Animals, London: Aquarian Press, ISBN 1-85538-118-4.

- Harding, Andrew (23 September 2006), "Beijing's Penis Emporium", BBC News, London: BBC.

- Levitt, Tom (26 February 2013), "Younger Generation Face Long Wait for Law-Change on Animal Cruelty", China Dialogue.

- Matthiessen, Peter (2000), Tigers in the Snow, Harvill, ISBN 978-1-86046-677-9.

- Nowell, K. (2007), Asian Big Cat Conservation and Trade Control in Selected Range States: Evaluating Implementation and Effectiveness of CITES Recommendations, TRAFFIC International.

- Qian, Jose (11 July 2018), "How Can Tigers and Rhinos Be Medicine?", Deutsche Welle, Bonn

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Tobias, Michael Charles (2 November 2012), "Animal Rights in China", Forbes.

- Weirum, Brian K. (11 November 2007), "Will Traditional Chinese Medicine Mean the End of the Wild Tiger?", SFGate, New York: Hearst Communications.

External links

- "The Tiger in Chinese Culture and Rock Art", Official site, Charlottesville: Bradshaw Foundation.