Hun and po

Hun (Chinese: 魂; pinyin: hún; Wade–Giles: hun; lit. 'cloud-soul') and po (Chinese: 魄; pinyin: pò; Wade–Giles: p'o; lit. 'white-soul') are types of souls in Chinese philosophy and traditional religion. Within this ancient soul dualism tradition, every living human has both a hun spiritual, ethereal, yang soul which leaves the body after death, and also a po corporeal, substantive, yin soul which remains with the corpse of the deceased. Some controversy exists over the number of souls in a person; for instance, one of the traditions within Daoism proposes a soul structure of sanhunqipo 三魂七魄; that is, "three hun and seven po". The historian Yü Ying-shih describes hun and po as "two pivotal concepts that have been, and remain today, the key to understanding Chinese views of the human soul and the afterlife".[1]

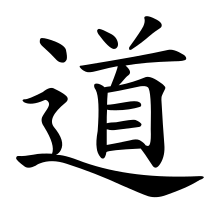

Characters

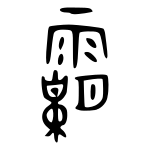

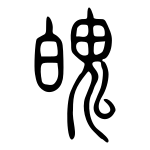

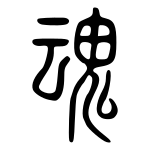

The Chinese characters 魂 and 魄 for hun and po typify the most common character classification of "radical-phonetic" or "phono-semantic" graphs, which combine a "radical" or "signific" (recurring graphic elements that roughly provide semantic information) with a "phonetic" (suggesting ancient pronunciation). Hun 魂 (or 䰟) and po 魄 have the "ghost radical" gui 鬼 "ghost; devil" and phonetics of yun 云 "cloud; cloudy" and bai 白 "white; clear; pure".

Besides the common meaning of "a soul", po 魄 was a variant Chinese character for po 霸 "a lunar phase" and po 粕 "dregs". The Book of Documents used po 魄 as a graphic variant for po 霸 "dark aspect of the moon" – this character usually means ba 霸 "overlord; hegemon". For example, "On the third month, when (the growth phase, 生魄) of the moon began to wane, the duke of Chow [i.e., Duke of Zhou] commenced the foundations, and proceeded to build the new great city of Lǒ".[2] The Zhuangzi "[Writings of] Master Zhuang" wrote zaopo 糟粕 (lit. "rotten dregs") "worthless; unwanted; waste matter" with a po 魄 variant. A wheelwright sees Duke Huan of Qi with books by dead sages and says, "what you are reading there is nothing but the [糟魄] chaff and dregs of the men of old!".[3]

In the history of Chinese writing, characters for po 魄/霸 "lunar brightness" appeared before those for hun 魂 "soul; spirit". The spiritual hun 魂 and po 魄 "dual souls" are first recorded in Warring States period (475–221 BCE) seal script characters. The lunar po 魄 or 霸 "moon's brightness" appears in both Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BCE) Bronzeware script and oracle bone script, but not in Shang dynasty (ca. 1600–1046 BCE) oracle inscriptions. The earliest form of this "lunar brightness" character was found on a (c. 11th century BCE) Zhou oracle bone inscription.[4]

Etymologies

The po soul's etymology is better understood than the hun soul's. Schuessler[5] reconstructs hun 魂 "'spiritual soul' which makes a human personality" and po 魄 "vegetative or animal soul ... which accounts for growth and physiological functions" as Middle Chinese γuən and pʰak from Old Chinese *wûn and *phrâk.

The (c. 80 CE) Baihu Tang 白虎堂 gave pseudo-etymologies for hun and po through Chinese character puns. It explains hun 魂 with zhuan 傳 "deliver; pass on; impart; spread" and yun 芸 "rue (used to keep insects out of books); to weed", and po 魄 with po 迫 " compel; force; coerce; urgent" and bai 白 "white; bright".

What do the words hun and [po] mean? Hun expresses the idea of continuous propagation ([zhuan] 傳), unresting flight; it is the qi of the Lesser Yang, working in man in an external direction, and it governs the nature (or the instincts, [xing] 性). [Po] expresses the idea of a continuous pressing urge ([po] 迫) on man; it is the [qi] of the Lesser Yin, and works in him, governing the emotions ([qing] 情). Hun is connected with the idea of weeding ([yun] 芸), for with the instincts the evil weeds (in man's nature) are removed. [Po] is connected with the idea of brightening ([bai] 白), for with the emotions the interior (of the personality) is governed.[6]

Etymologically, Schuessler says pò 魄 "animal soul" "is the same word as" pò 霸 "a lunar phase". He cites the Zuozhuan (534 BCE, see below) using the lunar jishengpo 既生魄 to mean "With the first development of a fetus grows the vegetative soul".

Pò, the soul responsible for growth, is the same as pò the waxing and waning of the moon". The meaning 'soul' has probably been transferred from the moon since men must have been aware of lunar phases long before they had developed theories on the soul. This is supported by the etymology 'bright', and by the inverted word order which can only have originated with meteorological expressions ... The association with the moon explains perhaps why the pò soul is classified as Yin ... in spite of the etymology 'bright' (which should be Yang), hun's Yang classification may be due to the association with clouds and by extension sky, even though the word invokes 'dark'. 'Soul' and 'moon' are related in other cultures, by cognation or convergence, as in Tibeto-Burman and Proto-Lolo–Burmese *s/ʼ-la "moon; soul; spirit", Written Tibetan cognates bla "soul" and zla "moon", and Proto-Miao–Yao *bla "spirit; soul; moon".[7]

Lunar associations of po are evident in the Classical Chinese terms chanpo 蟾魄 "the moon" (with "toad; toad in the moon; moon") and haopo 皓魄 "moon; moonlight" (with "white; bright; luminous").

The semantics of po 魄 "white soul" probably originated with 霸 "lunar whiteness". Zhou bronze inscriptions commonly recorded lunar phases with the terms jishengpo 既生魄 "after the brightness has grown" and jisipo 既死魄 "after the brightness has died", which Schuessler explains as "second quarter of the lunar month" and "last quarter of the lunar month". Chinese scholars have variously interpreted these two terms as lunar quarters or fixed days, and[8] Wang Guowei's lunar-quarter analysis the most likely. Thus, jishengpo is from the 7th/8th to the 14th/15th days of the lunar month and jisipo is from the 23rd/24th to the end of the month. Yü translates them as "after the birth of the crescent" and "after the death of the crescent".[4] Etymologically, lunar and spiritual po < pʰak < *phrâk 魄 are cognate with bai < bɐk < *brâk 白 "white".[9][10] According to Hu Shih, po etymologically means "white, whiteness, and bright light"; "The primitive Chinese seem to have regarded the changing phases of the moon as periodic birth and death of its [po], its 'white light' or soul."[11] Yü says this ancient association between the po soul and the "growing light of the new moon is of tremendous importance to our understanding of certain myths related to the seventh day of the months."[12] Two celebrated examples in Chinese mythology are Xi Wangmu and Emperor Wu meeting on the seventh day of the first lunar month and The Princess and the Cowherd or Qixi Festival held on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month.

The etymology of hun < γuən < *wûn 魂 is comparatively less certain. Hu said, "The word hun is etymologically the same as the word yun, meaning "clouds."[13] The clouds float about and seem more free and more active than the cold, white-lighted portion of the growing and waning moon." Schuessler cites two possibilities.

Since pò is the 'bright' soul, hún is the 'dark' soul and therefore cognate to yún 雲 'cloud',[14] perhaps in the sense of 'shadowy' because some believe that the hún soul will live after death in a world of shadows.[15][16]

Semantics

The correlative "soul" words hun 魂 and po 魄 have several meanings in Chinese plus many translations and explanations in English. The table below shows translation equivalents from some major Chinese-English dictionaries.

| Dictionary | Hun 魂 | Po 魄 |

|---|---|---|

| Giles[17] | The soul, that part of the soul (as opp. to 魄) which goes to heaven and is able to leave the body, carrying with it an appearance of physical form; the subliminal self, expl. as 人陽神. The mind; wits; faculties. | The soul; that part of the soul (as opposed to 魂) which is indissolubly attached to the body, and goes down to earth with it at death; the supraliminal self, expl. as 人陰神. Form; shape. The disc or substance of the moon from the time it begins to wane to new moon. |

| Mathews[18] | The soul, the spiritual part of man that ascends to heaven, as contrasted with 魄. The wits; the spiritual faculties. | The animal or inferior soul; the animal or sentient life which inheres in the body – the body in this sense; the animals spirits; this soul goes to the earth with the body. |

| Chao and Yang[19] | the soul (of a living person or of the dead) | the physical side of the soul |

| Karlgren[20] | spiritual soul (as opp. to 魄) | the animal soul of man (as opp. to 魂) |

| Lin[21] | Soul; the finer spirits of man as dist. 魄, the baser spirits or animal forces | (Taoism) the baser animal spirits of man, contrasted with finer elements 魂 (三魂七魄 three finer spirits and seven animal spirits), the two together conceived as animating the human body |

| Liang[22] | a soul; a spirit. | 1. (Taoism) vigor; animation; life. 2. form; shape; body. 3. the dark part of the moon. |

| Wu[23] | ① soul ② mood; spirit ③ the lofty spirit of a nation | ① soul ② vigour; spirit |

| Ling et al.[24] | ① same as 靈魂 ... soul; believed by the superstitious to be an immaterial spiritual entity distinguished from but coexistent with the physical body of a person and a dominant spiritual force, and which leaves upon the person's death. ② spirit; mood. ③ lofty spirit. | ① soul; spiritual matter believed by religious people as dependent on human's body. ② vigour; spirit. |

| DeFrancis[25] | soul, spirit; mood | ① soul; ② vigor; spirit |

Both Chinese hun and po are translatable as English "soul" or "spirit", and both are basic components in "soul" compounds. In the following examples, all Chinese-English translation equivalents are from DeFrancis.[25]

- hunpo 魂魄 "soul; psyche"

- linghun 靈魂 "soul; spirit"

- hunling 魂靈 "(colloquial) soul; ghost"

- yinhun 陰魂 "soul; spirit; apparition"

- sanhunqipo 三魂七魄 "soul; three finer spirits and several baser instincts that motivate a human being"

- xinpo 心魄 "soul"

Hunpo and linghun are the most frequently used among these "soul" words.

Joseph Needham and Lu Gwei-djen, eminent historians of science and technology in China,[26] define hun and po in modern terms. "Peering as far as one can into these ancient psycho-physiological ideas, one gains the impression that the distinction was something like that between what we would call motor and sensory activity on the one hand, and also voluntary as against vegetative processes on the other."

Farzeen Baldrian-Hussein cautions about hun and po translations: "Although the term "souls" is often used to refer to them, they are better seen as two types of vital entities, the source of life in every individual. The hun is Yang, luminous, and volatile, while the po is Yin, somber, and heavy."[27]

History

Origin of terms

Based on Zuozhuan usages of hun and po in four historical contexts, Yü extrapolates that po was the original name for a human soul, and the dualistic conception of hun and po "began to gain currency in the middle of the sixth century" BCE.[4]

Two earlier 6th century contexts used the po soul alone. Both describe Tian 天 "heaven; god" duo 奪 "seizing; taking away" a person's po, which resulted in a loss of mental faculties. In 593 BCE (Duke Xuan 15th year),[28] after Zhao Tong 趙同 behaved inappropriately at the Zhou court, an observer predicted: "In less than ten years [Zhao Tong] will be sure to meet with great calamity. Heaven has taken his [魄] wits away from him." In 543 BCE (Duke Xiang 29th year,[29] Boyou 伯有 from the state of Zheng acted irrationally, which an official interpreted as: "Heaven is destroying [Boyou], and has taken away his [魄] reason." Boyou's political enemies subsequently arranged to take away his hereditary position and assassinate him.

Two later sixth-century Zuozhuan contexts used po together with the hun soul. In 534 BCE, the ghost of Boyou 伯有 (above) was seeking revenge on his murderers, and terrifying the people of Zheng (Duke Zhao, Year &).[30] The philosopher and statesman Zi Chan, realizing that Boyou's loss of hereditary office had caused his spirit to be deprived of sacrifices, reinstated his son to the family position, and the ghost disappeared. When a friend asked Zi Chan to explain ghosts, he gave what Yu calls "the locus classicus on the subject of the human soul in the Chinese tradition".[31]

When a man is born, (we see) in his first movements what is called the [魄] animal soul. [既生魄] After this has been produced, it is developed into what is called the [魂] spirit. By the use of things the subtle elements are multiplied, and the [魂魄] soul and spirit become strong. They go on in this way, growing in etherealness and brightness, till they become (thoroughly) spiritual and intelligent. When an ordinary man or woman dies a violent death, the [魂魄] soul and spirit are still able to keep hanging about men in the shape of an evil apparition; how much more might this be expected in the case of [Boyou]. ... Belonging to a family which had held for three generations the handle of government, his use of things had been extensive, the subtle essences which he had imbibed had been many. His clan also was a great one, and his connexions [sic] were distinguished. Is it not entirely reasonable that, having died a violent death, he should be a [鬼] ghost?[32]

Compare the translation of Needham and Lu, who interpret this as an early Chinese discourse on embryology.

When a foetus begins to develop, it is (due to) the [po]. (When this soul has given it a form) then comes the Yang part, called hun. The essences ([qing] 情) of many things (wu 物) then give strength to these (two souls), and so they acquire the vitality, animation and good cheer (shuang 爽) of these essences. Thus eventually there arises spirituality and intelligence (shen ming 神明).[33]

In 516 BCE (Duke Zhao, Year 20), the Duke of Song and a guest named Shusun 叔孫 were both seen weeping during a supposedly joyful gathering. Yue Qi 樂祁, a Song court official, said:

This year both our ruler and [Shusun] are likely to die. I have heard that joy in the midst of grief and grief in the midst of joy are signs of a loss of [xin 心] mind. The essential vigor and brightness of the mind is what we call the [hun] and the [po]. When these leave it, how can the man continue long?[34]

Hu proposed, "The idea of a hun may have been a contribution from the southern peoples" (who originated Zhao Hun rituals) and then spread to the north sometime during the sixth century BCE.[35] Calling this southern hypothesis "quite possible", Yü cites the Chuci, associated with the southern state of Chu, demonstrating "there can be little doubt that in the southern tradition the hun was regarded as a more active and vital soul than the p'o.[36] The Chuci uses hun 65 times and po 5 times (4 in hunpo, which the Chuci uses interchangeably with hun).[37]

Relation to yin-yang

The identification of the yin-yang principle with the hun and po souls evidently occurred in the late fourth and early third centuries BCE,[38] and by "the second century at the latest, the Chinese dualistic conception of soul had reached its definitive formulation." The Liji (11), compounds hun and po with qi "breath; life force" and xing "form; shape; body" in hunqi 魂氣 and xingpo 形魄. "The [魂氣] intelligent spirit returns to heaven the [形魄] body and the animal soul return to the earth; and hence arose the idea of seeking (for the deceased) in sacrifice in the unseen darkness and in the bright region above."[39] Compare this modern translation,[38] "The breath-soul (hun-ch'I 魂氣) returns to heaven; the bodily soul (hsing-p'o 形魄) returns to earth. Therefore, in sacrificial-offering one should seek the meaning in the yin-yang 陰陽 principle." Yü summarizes hun/po dualism.

Ancient Chinese generally believed that the individual human life consists of a bodily part as well as a spiritual part. The physical body relies for its existence on food and drink produced by the earth. The spirit depends for its existence on the invisible life force called ch'i, which comes into the body from heaven. In other words, breathing and eating are the two basic activities by which a man continually maintains his life. But the body and the spirit are each governed by a soul, namely, the p'o and the hun. It is for this reason that they are referred to in the passage just quoted above as the bodily-soul (hsing-p'o) and the breath-soul (hun-ch'i) respectively.[40]

Loewe explains with a candle metaphor; the physical xing is the "wick and substance of a candle", the spiritual po and hun are the "force that keeps the candle alight" and "light that emanates from the candle".[41]

Traditional medical beliefs

The Yin po and Yang hun were correlated with Chinese spiritual and medical beliefs. Hun 魂 is associated with shen 神 "spirit; god" and po 魄 with gui 鬼 "ghost; demon; devil".[14] The (c. 1st century BCE) Lingshu Jing medical text spiritually applies Wu Xing "Five Phase" theory to the Zang-fu "organs", associating the hun soul with liver (Chinese medicine) and blood, and the po soul with lung (Chinese medicine) and breath.

The liver stores the blood, and the blood houses the hun. When the vital energies of the liver are depleted, this results in fear; when repleted, this results in anger. ... The lungs store the breath, and the breath houses the po. When the vital energies of the lungs are depleted, then the nose becomes blocked and useless, and so there is diminished breath; when they are repleted, there is panting, a full chest, and one must elevate the head to breathe.[42]

The Lingshu Jing[43] also records that the hun and po souls taking flight can cause restless dreaming, and eye disorders can scatter the souls causing mental confusion. Han medical texts reveal that hun and po departing from the body does not necessarily cause death but rather distress and sickness. Brashier parallels the translation of hun and po, "If one were to put an English word to them, they are our 'wits', our ability to demarcate clearly, and like the English concept of "wits," they can be scared out of us or can dissipate in old age."[44]

Burial customs

During the Han Dynasty, the belief in hun and po remained prominent, although there was a great diversity of different, sometimes contradictory, beliefs about the afterlife.[45][46] Han burial customs provided nourishment and comfort for the po with the placement of grave goods, including food, commodities, and even money within the tomb of the deceased.[45] Chinese jade was believed to delay the decomposition of a body. Pieces of jade were commonly placed in bodily orifices, or rarely crafted into jade burial suits.

Separation at death

Generations of sinologists have repeatedly asserted that Han-era people commonly believed the heavenly hun and earthly po souls separated at death, but recent scholarship and archeology suggest that hunpo dualism was more an academic theory than a popular faith. Anna Seidel analyzed funerary texts discovered in Han tombs, which mention not only po souls but also hun remaining with entombed corpses, and wrote, "Indeed, a clear separation of a p'o, appeased with the wealth included in the tomb, from a hun departed to heavenly realms is not possible."[47] Seidel later called for reappraising Han abstract notions of hun and po, which "do not seem to have had as wide a currency as we assumed up to now."[48] Pu Muzhou surveyed usages of the words hun and po on Han Dynasty bei 碑 "stele" erected at graves and shrines, and concluded, "The thinking of ordinary people seems to have been quite hazy on the matter of what distinguished the hun from the po."[49][50] These stele texts contrasted souls between a corporeal hun or hunpo at the cemetery and a spiritual shen at the family shrine. Kenneth Brashier reexamined the evidence for hunpo dualism and relegated it "to the realm of scholasticism rather than general beliefs on death."[51] Brashier cited several Han sources (grave deeds, Book of the Later Han, and Jiaoshi Yilin) attesting beliefs that "the hun remains in the grave instead of flying up to heaven", and suggested it "was sealed into the grave to prevent its escape."[52] Another Han text, the Fengsu Tongyi says, "The vital energy of the hun of a dead person floats away; therefore a mask is made in order to retain it.

Hun and po souls, explains Yü, "are regarded as the very essence of the mind, the source of knowledge and intelligence. Death is thought to follow inevitably when the hun and the p'o leave the body. We have reason to believe that around this time the idea of hun was still relatively new."[53]

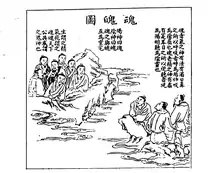

Soon after death, it was believed that a person's hun and po could be temporarily reunited through a ritual called the fu 復 "recall; return", zhaohun 招魂 "summon the hun soul", or zhaohun fupo 招魂復魄 "to summon the hun-soul to reunite with the po-soul". The earliest known account of this ritual is found in the (3rd century BCE) Chuci poems Zhao Hun 招魂 "Summons of the Soul" and Dazhao 大招 "The Great Summons".[55] For example, the wu Yang (巫陽) summons a man's soul in the "Zhao Hun".

O soul, come back! Why have you left your old abode and sped to the earth's far corners, deserting the place of your delight to meet all those things of evil omen?

O soul, come back! In the east you cannot abide. There are giants there a thousand fathoms tall, who seek only for souls to catch, and ten suns that come out together, melting metal, dissolving stone ...

O soul, come back! In the south you cannot stay. There the people have tattooed faces and blackened teeth, they sacrifice flesh of men, and pound their bones to paste ...

O soul, come back! For the west holds many perils: The Moving Sands stretch on for a hundred leagues. You will be swept into the Thunder's Chasm and dashed in pieces, unable to help yourself ...

O soul, come back! In the north you may not stay. There the layered ice rises high, and the snowflakes fly for a hundred leagues and more...

O soul, come back! Climb not to heaven above. For tigers and leopards guard the gates, with jaws ever ready to rend up mortal men ...

O soul, come back! Go not down to the Land of Darkness, where the Earth God lies, nine-coiled, with dreadful horns on his forehead, and a great humped back and bloody thumbs, pursuing men, swift-footed ...[56]

Daoism

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

Hun 魂 and po 魄 spiritual concepts were important in several Daoist traditions. For instance, "Since the volatile hun is fond of wandering and leaving the body during sleep, techniques were devised to restrain it, one of which entailed a method of staying constantly awake."[57]

The sanhunqipo 三魂七魄 "three hun and seven po" were anthropomorphized and visualized. Ge Hong's (c. 320 CE) Baopuzi frequently mentions the hun and po "ethereal and gross souls". The "Genii" Chapter argues that the departing of these dual souls cause illness and death.

All men, wise or foolish, know that their bodies contain ethereal as well as gross breaths, and that when some of them quit the body, illness ensues; when they all leave him, a man dies. In the former case, the magicians have amulets for restraining them; in the latter case, The Rites [i.e., Yili] provide ceremonials for summoning them back. These breaths are most intimately bound up with us, for they are born when we are, but over a whole lifetime probably nobody actually hears or sees them. Would one conclude that they do not exist because they are neither seen nor heard? (2)[58]

This "magicians" translates fangshi 方士 "doctor; diviner' magician". Both fangshi and daoshi 道士 "Daoist priests" developed methods and rituals to summon hun and po back into a person's body. The "Gold and Cinnabar" chapter records a Daoist alchemical reanimation pill that can return the hun and po souls to a recent corpse: Taiyi zhaohunpo dan fa 太乙招魂魄丹法 "The Great One's Elixir Method for Summoning Souls".

In T'ai-i's elixir for Summoning Gross and Ethereal Breaths the five minerals [i.e., cinnabar, realgar, arsenolite, malachite, and magnetite] are used and sealed with Six-One lute as in the Nine-crucible cinnabars. It is particularly effective for raising those who have died of a stroke. In cases where the corpse has been dead less than four days, force open the corpse's mouth and insert a pill of this elixir and one of sulphur, washing them down its gullet with water. The corpse will immediately come to life. In every case the resurrected remark that they have seen a messenger with a baton of authority summoning them. (4)[59]

For visualizing the ten souls, the Baopuzi "Truth on Earth" chapter recommends taking dayao 大藥 "great medicines" and practicing a fenxing "divide/multiply the body" multilocation technique.

My teacher used to say that to preserve Unity was to practice jointly Bright Mirror, and that on becoming successful in the mirror procedure a man would be able to multiply his body to several dozen all with the same dress and facial expression. My teacher also used to say that you should take the great medicines diligently if you wished to enjoy Fullness of Life, and that you should use metal solutions and a multiplication of your person if you wished to communicate with the gods. By multiplying the body, the three Hun and the seven Po are automatically seen within the body, and in addition it becomes possible to meet and visit the powers of heaven and the deities of earth and to have all the gods of the mountains and rivers in one's service. (18)[60]

The Daoist Shangqing School has several meditation techniques for visualizing the hun and po. In Shangqing Neidan "Internal Alchemy", Baldrian-Hussein says,

the po plays a particularly somber role as it represents the passions that dominate the hun. This causes the vital force to decay, especially during sexual activity, and eventually leads to death. The inner alchemical practice seeks to concentrate the vital forces within the body by reversing the respective roles of hun and po, so that the hun (Yang) controls the po (Yin).[61]

Number of souls

The number of human "souls" has been a long-standing source of controversy among Chinese religious traditions. Stevan Harrell concludes, "Almost every number from one to a dozen has at one time or another been proposed as the correct one."[62] The most commonly believed numbers of "souls" in a person are one, two, three, and ten.

One "soul" or linghun 靈魂 is the simplest idea. Harrell gives a fieldwork example.

When rural Taiwanese perform ancestral sacrifices at home, they naturally think of the ling-hun in the tablet; when they take offerings to the cemetery, they think of it in the grave; and when they go on shamanistic trips, they think of it in the yin world. Because the contexts are separate, there is little conflict and little need for abstract reasoning about a nonexistent problem.[63]

Two "souls" is a common folk belief, and reinforced by yin-yang theory. These paired souls can be called hun and po, hunpo and shen, or linghun and shen.

Three "souls" comes from widespread beliefs that the soul of a dead person can exist in the multiple locations. The missionary Justus Doolittle recorded that Chinese people in Fuzhou

Believe each person has three distinct souls while living. These souls separate at the death of the adult to whom they belong. One resides in the ancestral tablet erected to his memory, if the head of a family; another lurks in the coffin or the grave, and the third departs to the infernal regions to undergo its merited punishment.[64]

Ten "souls" of sanhunqipo 三魂七魄 "three hun and seven po" is not only Daoist; "Some authorities would maintain that the three-seven "soul" is basic to all Chinese religion".[65] During the Later Han period, Daoists fixed the number of hun souls at three and the number of po souls at seven. A newly deceased person may return (回魂) to his home at some nights, sometimes one week (頭七) after his death and the seven po would disappear one by one every 7 days after death. According to Needham and Lu, "It is a little difficult to ascertain the reason for this, since fives and sixes (if they corresponded to the viscera) would have rather been expected."[26] Three hun may stand for the sangang 三綱 "three principles of social order: relationships between ruler-subject, father-child, and husband-wife".[66] Seven po may stand for the qiqiao 七竅 "seven apertures (in the head, eyes, ears, nostrils, and mouth)" or the qiqing 七情 "seven emotions (joy, anger, sorrow, fear, worry, grief, fright)" in traditional Chinese medicine.[57] Sanhunqipo also stand for other names.

See also

- Soul dualism, similar beliefs in other animism belief systems.

- Mitama

- Ancient Egyptian beliefs about the soul, in which the soul has many parts

- Baci, a religious ceremony in Laos practiced to synchronize the effects of the 32 souls of an individual person, known as kwan.

- Diyu, the Chinese underworld, eventually understood as a form of Hell

- Heaven, known in modern Chinese as Tiantang

- "Hymn to the Fallen" a piece from Chuci, featuring hunpo being steadfast and acting as hero-ghosts (魂魄毅...為鬼雄).

- Mingqi, traditional Chinese grave goods

- "The Great Summons" a Chuci piece focused on the hun.

- Ti bon ange and the gros bon ange in Haitian Vodou; Soul dualism in Haitian Vodou.

- "Zhao Hun", a Chuci poem focused on the hun.

References

- Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen (2008). "Hun and po 魂•魄 Yang soul(s) and Yin soul(s); celestial soul(s) and earthly soul(s)". In Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. pp. 521–523. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Brashier, Kenneth E. (1996). "Han Thanatology and the Division of "Souls"". Early China. 21: 125–158. doi:10.1017/S0362502800003424. S2CID 146161610.

- Carr, Michael (1985). "Personation of the Dead in Ancient China". Computational Analysis of Asian & African Languages. 24: 1–107.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark (2006). Readings in Han Chinese Thought. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 9781603843485.

- Harrell, Stevan (1979). "The Concept of Soul in Chinese Folk Religion". The Journal of Asian Studies. 38 (3): 519–528. doi:10.2307/2053785. JSTOR 2053785. S2CID 162507447.

- Hu, Shih (1946). "The Concept of Immortality in Chinese Thought". Harvard Divinity School Bulletin (1945–1946): 26–43.

- The Chinese Classics, Vol. V, The Ch'un Ts'ew with the Tso Chuen. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1872.

- Needham, Joseph; Lu, Gwei-djen (1974). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 2, Spagyrical Discovery and Inventions: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521085717. Review at Oxford Academic.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. Honolulu HI: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824829759.

- Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei Pien of Ko Hung. Translated by Ware, James R. MIT Press. 1966. ISBN 9780262230223.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1981). "New Evidence on the Early Chinese Conception of Afterlife: A Review Article". The Journal of Asian Studies. 41 (1): 81–85. doi:10.2307/2055604. JSTOR 2055604. S2CID 163220003.

- Yü, Ying-Shih (1987). "O Soul, Come Back! A Study in the Changing Conceptions of the Soul and Afterlife in Pre-Buddhist China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 47 (2): 363–395. doi:10.2307/2719187. JSTOR 2719187.

Footnotes

- Yü 1987, p. 363.

- The Chinese Classics, Vol. III, The Shoo King. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1865. p. 434.

- The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Watson, Burton. Columbia University Press. 1968. p. 152. ISBN 9780231031479.

- Yü 1987, p. 370.

- Schuessler 2007, pp. 290, 417.

- Tr. Needham & Lu 1974, p. 87.

- Schuessler 2007, p. 417.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1992). Sources of Western Zhou history: Inscribed Bronze Vessels. University of California Press. pp. 136–45. ISBN 978-0520070288.

- Matisoff, James (1980). "Stars, Moon, and Spirits: Bright Beings of the Night in Sino-Tibetan". Gengo Kenkyu. 77: 1–45.

- Yü 1981; Carr 1985.

- Hu 1946, p. 30.

- Yü 1981, p. 83.

- Hu 1946, p. 31.

- Carr 1985, p. 62.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1967). Guilt and Sin in Traditional China. University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780520003712.

- Schuessler 2007, p. 290.

- Giles, Herbert A. (1912). A Chinese-English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Kelly & Walsh.

- Mathews, Robert H. (1931). Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary. Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Chao, Yuen Ren; Yang, Lien-sheng (1947). Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese. Harvard University Press.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1957). Grammata Serica Recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.

- Lin, Yutang (1972). Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage. Chinese University of Hong Kong. ISBN 0070996954.

- Liang, Shiqiu (1992). Far East Chinese-English Dictionary (revised ed.). Far East Book. ISBN 978-9576122309.

- Wu, Guanghua (1993). Chinese-English Dictionary. Vol. 2 volumes. Shanghai Jiaotong University Press.

- Ling, Yuan; et al. (2002). The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (Chinese-English ed.). Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. ISBN 978-7560031958.

- DeFrancis, John (2003). ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824827663.

- Needham & Lu 1974, p. 88.

- Baldrian-Hussein 2008, p. 521.

- Legge 1872, p. 329.

- Legge 1872, p. 551.

- Legge 1872, p. 618.

- Yu 1972, p. 372.

- Yu 1972, p. 372.

- Needham & Lu 1974, p. 86.

- Legge 1872, p. 708.

- Hu 1946, pp. 31–2.

- Yü 1987, p. 373.

- Brashier 1996, p. 131.

- Yü 1987, p. 374.

- Sacred Books of the East. Volume 27: The Li Ki (Book of Rites), Chs. 1–10. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1885. p. 444.

- Yü 1987, p. 376.

- Loewe, Michael (1979). Ways to Paradise, the Chinese Quest for Immortality. Unwin Hyman. p. 9. ISBN 978-0041810257.

- Tr. Brashier 1996, p. 141.

- Brashier 1996, p. 142.

- Brashier 1996, pp. 145–6.

- Hansen, Valerie (2000). The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 119. ISBN 9780393973747.

- Csikszentmihalyi 2006, pp. 116–7, 140–2.

- Seidel, Anna (1982). "Review: Tokens of Immortality in Han Graves". Numen. 29 (1): 79–122. p. 107.

- Seidel, Anna (1987). "Post-mortem Immortality, or: The Taoist Resurrection of the Body". In Shulman, Shaked D.; Strousma, G. G. (eds.). GILGUL: Essays on Transformation, Revolution and Permanence in the History of Religions. Brill. pp. 223–237. ISBN 9789004085091. p. 227.

- Pu, Muzhou 蒲慕州 (1993). Muzang yu shengsi: Zhongguo gudai zongjiao zhi xingsi 墓葬與生死: 中國古代宗教之省思 (in Chinese). Lianjing. p. 216.

- Tr. Brashier 1996, p. 126.

- Brashier 1996, p. 158.

- Brashier 1996, pp. 136–7.

- Yü 1987, p. 371.

- Yü 1987, p. 367.

- Csikszentmihalyi 2006, pp. 140–1.

- The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Translated by Hawkes, David. Penguin. 2011 [1985]. pp. 244–5. ISBN 9780140443752.

- Baldrian-Hussein 2008, p. 522.

- Ware 1966, pp. 49–50.

- Ware 1966, p. 87.

- Ware 1966, p. 306.

- Baldrian-Hussein 2008, p. 523.

- Harrell 1979, p. 521.

- Harrell 1979, p. 523.

- Doolittle, Justus (1865). The Social Life of the Chinese. Harper. II pp. 401-2. Reprint by Routledge 2005, ISBN 9780710307538.

- Harrell 1979, p. 522.

- Needham & Lu 1974, p. 89.

Further reading

- Schafer, Edward H. (1977). Pacing the Void: T'ang Approaches to the Stars. University of California Press.

External links

- page 1461, Kangxi Dictionary entries for hun and po

- What Is Shen (Spirit)?, Appendix: Hun and Po

- The Indigenous Chinese Concepts of Hun and P'o Souls, Singapore Paranormal Investigators – link obsolete – Internet Archive copy, Singapore Paranormal Investigators – link obsolete – Internet Archive copy

- 佛說地藏菩薩發心因緣十王經, Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association(in Chinese)