Timeline of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California

The following is a timeline of the history of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, United States.

| Date | Event | Image | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century | Esselen-speaking people were the first Native Americans to inhabit the area of Carmel, but the Ohlone people pushed them south into the mountains of Big Sur around the 6th century. |  |

[1] |

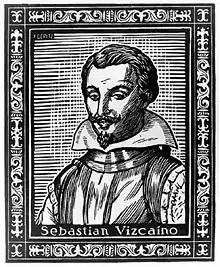

| 1602 | Spanish explorer, Sebastián Vizcaíno discovered for Spain what is now known as Carmel Valley in 1602. It is thought that he named the river running through the valley Rio Carmelo in honor of the three Carmelite friars serving as chaplains for the voyage. |  |

[2] |

| 1770 | The Spanish did not attempt to colonize the area until 1770, when Gaspar de Portolá, along with Franciscan priests Junípero Serra and Juan Crespí, visited the area in search of a mission site. Portolà and Crespí traveled by land while Serra traveled with the Mission supplies aboard ship, leaving San Diego on April 16, 1770. The colony of Monterey was established at the same time as the second mission in Alta California and soon became the capital of California, remaining so until 1849. |  |

[3] |

| 1771 | Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo was moved from Monterey to Carmel on August 1, 1771; the first mass was celebrated on August 24, and Junípero Serra officially took up residence in the newly constructed buildings on December 24, 1771. |  |

[3] |

| 1842 | James Meadows and his wife purchased the 4,592 acres (1,858 ha) Palo Escrito Mexican land grant from Monterey businessman Thomas O. Larkin who had acquired several land grants in California. It was later called the James Meadows Tract. | .jpg.webp) |

[4][5]: p195 |

| 1848 | Carmel became part of the United States on February 2, 1848, when Mexico ceded California as a result of the Mexican–American War. | [6] | |

| 1852 | The Mission Ranch once included 160-acre (0.65 km2), was owned by Juan Romero, a native American. In 1852, Romero deeded the property to William J. Curtis, a Monterey storekeeper, for $300 (equivalent to $10,553 in 2022). |  |

[7] |

| 1853 | Known as "Rancho Las Manzanitas", the unoccupied area of wooden hills that became Carmel-by-the-Sea was purchased by French businessman Honoré Escolle in the ca. 1853. He bought the land for pasturage and firewood. | .jpg.webp) |

[8] |

| 1859 | William Martin of Scotland arrived in Monterey in 1856 by ship with his family. His son, John Martin, bought land around the Carmel River in 1859 from broker Lafayette F. Loveland. He built the Martin Ranch on 216-acre (0.87 km2) that went as far as the Carmel River to the homes along Carmel Point. The ranch became known as the Mission Ranch because it was so close to the Carmel Mission. They farmed potatoes and barley and had a milk dairy. |  |

[9][10] |

| 1870 | The United States government patent gave the Carmel Mission Church 7-acre (0.028 km2) of land. |  |

[5] |

| 1873 | David Jacks acquired 36,000 acres (14,569 ha) of land in Monterey County. He started cutting up large tracts of land below Salinas into ranches for farmers to buy or rent. He helped found what is now known as Pebble Beach. In 1880, he sold 7,000 acres (2,833 ha) of land between Carmel-by-the-Sea and Pacific Grove to the Pacific Improvement Company. |  |

[11][12] |

| 1880 | The branch line of the Southern Pacific Railroad between Castroville and Monterey, California was completed. It was called the Del Monte Express. Charles Crocker chose Monterey as the site for a new seaside luxury hotel, which would be called the Hotel Del Monte. It was thought that the Southern Pacific would extend the line to Carmel. |  |

[13][5]: p220 |

| 1884 | Work began on the repair of the Carmel Mission Church. Leland Stanford led the fund-raising effort that involved more than 50 citizens of California. |  |

[5] |

| 1888 | The Pacific Improvement Company hired William Hatton in 1888 to manage two large Del Monte dairies, the Rancho Cañada de la Segunda in lower Carmel Valley and the ranching operations of Rancho Los Laureles in the middle of Carmel Valley that the company purchased in 1882. The Del Monte Dairy became the sole supplier of milk for the Hotel Del Monte. |  |

[5][14] |

| 1888 | Escolle and Santiago J. Duckworth, a young developer from Monterey with dreams of establishing a Catholic retreat near the Carmel Mission, signed an agreement to sell 324 acres (131 ha) to Duckworth and his brother on February 18, 1888. The land began at the top of the Carmel Hill and ran past the boundary of the Hatton Ranch, down through Ocean Avenue to Junipero Avenue. On May 1, 1888, they filed a subdivision map with the County Recorder of Monterey County. |  |

[14][15] |

| 1889 | In December 1889, Duckworth sold 200 lots and reserved five lots on the north side of Broadway Avenue (now Junipero), between 6th Avenue and Ocean Avenue for Carmel City's first two-story hotel, Hotel Carmelo (now the Pine Inn). |  |

[8][5] |

| 1889 | Abbie Jane Hunter, a realtor from San Francisco, bought seven Carmel City lots. She became a real estate associate with Duckworth, to help build a Catholic summer resort called Carmel City. |  |

[8]: p9, 15 |

| 1889 | In 1889, Carpenter Delos Goldsmith (1828–1923), an uncle to Abbie Jane Hunter, built the Carmel bathhouse above the beach at the foot of Ocean Avenue to attract visitors to Carmel City. Hunter's son, Wesley R. Hunter (1876–1966) helped build it. It was torn down in 1929. |  |

[8]: p15 [16] |

| 1889 | The first United States Post Office Department Office called Carmel opened in 1889, closed in 1890, re-opened in 1893, and moved in 1902. |  |

[17][8] |

| 1890 | In 1890, Carmel City trees were removed and an outline marked for the construction of Ocean Avenue heading east up the hill. Hotel Carmelo was one of the first buildings constructed along Ocean Avenue. |  |

[18] |

| 1892 | Abbie Jane Hunter used the name Carmel-by-the-Sea in advertisements for the first. She founded the Women's Real Estate Investment Company and acquired 164-acre (0.66 km2) of the Carmel City Tract. | [8]: p16 [19]: p32 | |

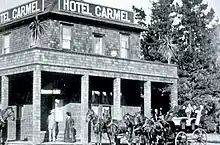

| 1898 | The Hotel Carmel, (now the Goold Building), dates to 1898 when pioneer D. W. Johnson built a shingled two-story hotel on the corner of San Carlos Street and Ocean Avenue. The hotel was later purchased by Charles O. Goold. |  |

[14] |

| 1902 | City was founded in 1902. San Francisco attorney Frank Hubbard Powers purchased all the unsold land in Carmel with real estate developer James Franklin Devendorf who became his partner. They formed the Carmel Development Company on November 25, 1902, and established the artists and writers' colony that became Carmel-by-the-Sea, in 1903. | .jpg.webp) |

[20][14]: p8 [5]: p222 |

| 1902 (or 1903) | Richardson Log Cabin, is a historic building that was built in 1902 (or 1903), by George H. Richardson, an Alameda attorney. The structure is recognized as one of the oldest residential buildings in Carmel and the earliest known residence of American poet Robinson Jeffers and his wife Una. |  |

[21] |

| 1903 | The Carmel Development Company Building was the first "modern" commercial building in Carmel built by Thomas Albert Work of Pacific Grove, California, in 1902–1903, on the northwest corner of San Carlos Street and Ocean Avenue. |  |

[19] |

| 1903 | Louis S. Slevin decides to make Carmel his home. He was the first to open a general merchandise store in 1905, the first postmaster, first express agent, and first city treasurer. His collection of photographs of Carmel from 1903 to 1840 is recognized as historically important. |  |

[14] |

| 1903 | The El Carmelo Hotel was moved closer to the Carmel beach to the corner of Ocean Avenue and Monte Verde Street. Devendorf renamed the hotel the Pine Inn. |  |

[22] |

| 1904 | Frank Powers purchased a pine log farmhouse near the Carmel beachfront, off San Antonio Avenue, between 2nd and 4th Avenues, called "The Dunes," (which still exists today). Irish pioneer Matthew M. Murphey's nephew John Monroe Murphy and his wife, Ann Murphy, built the farmhouse on the land ca. 1872. By 1904, Frank Powers purchased the farmhouse and completed a restoration in 1907. The structure was used as the first Carmel artist studio for his artist-wife, Jane Gallatin Powers. |  |

[8][14] |

| 1905 | The Carmel Arts and Crafts Club was founded in 1905, by Elsie Allen, a former art instructor for Wellesley College. The club was located at Monte Verde Street where the Golden Bough Playhouse is today. The clubhouse served as the Carmel community cultural center. Between 1919 and 1948 Carmel was the largest art colony on the Pacific coast. |  |

[23] |

| 1905 | Writers Mary Austin, Jack London, James Hooper, Arnold Genthe, and George Sterling came to Carmel. In 1905, Sterling bought property between 10th and 11th Avenues. Austin bought a log cabin on North Lincoln Avenue. |  |

[5]: 241 |

| 1905 | Philip Wilson Sr. (1862–1944), established one of the first real estate office, in what is now called the Philip Wilson Building, on the corner of Ocean Avenue and Dolores Street. |  |

[24] |

| 1905 | David Starr Jordan, the first president of Stanford University, built his home on Camino Real and 7th Avenue in 1905. Others followed, including Stanford botany professor George James Peirce, who built his home around 1910 on Camino Real in Carmel-by-the-Sea. |  |

[8]: p24 |

| 1906 | The Sunset School was Carmel's first public school founded in 1904, moving in 1906 to San Carlos Street. In 1907, there were only 30 children and one teacher. |  |

[20] |

| 1906 | Fritz Schweninger (1867–1918) opened the first Carmel Bakery in what is now called the Schweninger Building. The two-story Vernacular-style building is on Ocean Avenue between Dolores and Lincoln Streets. His son Ernest Schweninger worked in Schweninger's Grocery and continued to operate the Carmel Bakery when his parents died. | .jpg.webp) |

[25][24] |

| 1906 | In 1906, Robert George Leidig (1879-1970) and his brother Fred, opened the Carmel-by-the-Sea's first Grocery Store on the north side of Ocean Avenue and Lincoln Street. In 1925, his wife Isabel A. Martin-Leidig (1884–1961) was the original owner of the Isabel Leidig Building. Robert and Isabel also built the Spanish Revival style Draper Leidig Building in 1929, on the east side of Dolores Street near Ocean Avenue. |  |

[19] |

| 1907 | Frederick R. Bechdolt and his wife moved to Carmel in 1907, and built a home in the Eighty Acres tract of Carmel. Bechdolt and James Hopper wrote the fictional novel 9009 (1908) about the condition of American prisons and the need for reform. |  |

[10]: p143 |

| 1908 | George W. Reamer (1864–1938) along with Florence E. Wells (1864–1966), built Driftwood Cottage, the first house built in 1908, on Carmel Point, at the corner of Scenic Drive and Ocean View Avenue, fronting the Carmel River lagoon. At this time there were no trees, electricity, gas, or paved roads on Carmel Point. |  |

[26][8] |

| 1908 | Grace and Alice MacGowan move to Carmel with their mother. They wrote short stories, novels and poems. Popular novels included The Straight Road and The Trail of the Little Wagon. |  |

[27] |

| 1908 | Writer, actor, and poet Herbert Heron came to Carmel in 1908. James Franklin Devendorf sold him a lot to build a house where he lived with his wife and daughter. |  |

[28] |

| 1908 | Carmel fire department was established in 1908 by twenty citizens that was led by Robert George Leidig (1879–1970). | [14] | |

| 1909 | Ocean Avenue in 1909. Pine trees were planted by Frank Devendorf down Ocean Avenue's main street center divide. Businesses were set up to serve the growing community. |  |

[5]: p236 |

| 1910 | Dr. Daniel T. MacDougal of the Carnegie Institution established the Coastal Botanical Laboratory at the Outlands in the Eighty Acres, with some scientists moving to the Carmel area. |  |

[29] |

| 1910 | The Forest Theater Society was founded by Herbert Heron. The first theatrical production, David and Saul, a biblical drama by Constance Lindsay Skinner under the direction of Garnet Holme of Berkeley, inaugurated the Forest Theater on July 9, 1910 |  |

[5][30] |

| 1913 | Carmel City Hall was established in July 1913 as the All Saints Episcopal Church located on Monte Verde Street and 7th Avenue. |  |

[20] |

| 1914 | Photographer Lewis Josselyn moved with his family to Carmel in 1914. He was the official photographer for the Forest Theater Society. Josselyns' photographs are an important record of the Carmel's historical past. |  |

[31] |

| 1914 | From July through September 1914, painter William Merritt Chase taught his last summer class, his largest with over one hundred pupils, at the Carmel Arts and Crafts Club's Summer School Of Art. |  |

[32] |

| 1914 | Philip Wilson Sr. (1862–1944) (of the Philip Wilson Building), purchased a writers studio at 14th Ave. and San Antonio Street in Carmel Point, from writer John Fleming Wilson (1877–1922). It was called "Point Loeb" after one of the many professors who had summer homes on Professors' Row. Wilson Sr., converted the studio into a clubhouse for the first and only Carmel Golf Course. It was sold when Wilson Sr., went into service during World War I. The land was subdivided into lots and the clubhouse became a one bedroom residence in 1990. |  |

[33] |

| 1915 | The Carmel Pine Cone was founded in 1915 by William Overstreet who proclaimed in the first four-page edition of 300 copies, "we are here to stay!" | .pdf.jpg.webp) |

[34] |

| 1916 | Samuel Finley Brown Morse became manager of the Pacific Improvement Company, in charge of liquidating many of their assets. He formed his own company, Del Monte Properties, in 1919, to acquire these assets. Funded by Herbert Fleishhacker, he bought 7,000 acres (28 km2) on the Monterey Coast including the Hotel Del Monte, Pacific Grove, Pebble Beach and the 11,000-acre (45 km2) Rancho Laureles, now the Carmel Valley Village, and the Monterey County Water Works, all for $1.34 million. |  |

[35] |

| 1916 | City was incorporated on October 31, 1916. Alfred P. Frazer became first Mayor of Carmel. |  |

[17][5][36] |

| 1916 | August Englund served as Carmel's first police chief and one-man police department, dedicated to ensuring the safety and security of Carmel for nearly 20 years. |  |

[28] |

| 1916 | La Playa Hotel, dates to 1905 when artist Chris Jorgensen (1860–1935) and his wife built the two-story wood-framed, ell shaped stone mansion on the southwest corner of El Camino Real and 8th Avenue. Agnes Signor bought the La Playa Hotel in 1916 and converted it into a boarding house called "The Strand." In 1922, Signor added twenty new rooms making it into a full-service hotel. |  |

[37] |

| 1919 | Robinson Jeffers and his wife Una bought land at Carmel Point in Spring 1919, and in mid-May they contracted Mike Murphy to build the first part of the Tor House, a stone two-story cottage at Carmel Point. Murphy's stonemason began work on the house immediately and, with Jeffers signing on later as an apprentice, was able to complete the project by mid-August. |  |

[20]: p57 [28]: p18 |

| 1920 | In 1920, Carmel-by-the-Sea had a total population of 638. |  |

[38] |

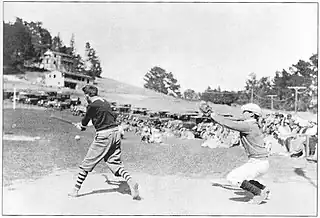

| 1921 | The Abalone League was a baseball and softball league based in Carmel Point from 1921 through 1938. It was the first softball league in the Western United States. The League was a Carmel focal point for many years. Early players included writers Jimmy Hopper and Harry Leon Wilson, actor Frank Sheridan, developer of Pebble Beach S. F. B. Morse, Philip Wilson, Sr., of the Philip Wilson Building, Col. Fletcher Dutton, and Fred and Harrison Godwin of the La Playa Hotel. |  |

[39][40] |

| 1922 | A city planning commission was established to protect Carmel from over commercialization. Perry Newberry, concerned about Carmel's growth, entered city politics. | [5] | |

| 1922 | Carmel Woods was laid out in 1922 by developer Samuel F. B. Morse (1885–1969). It included a 25-acre (0.10 km2) subdivision with 119 building lots. Carmel Woods was one of three major land developments adjacent to the Carmel city limits between 1922 and 1925. The other two were the Hatton Fields, a 233 acres (94 ha) between the eastern town limit and Highway 1, and the Walker Tract to the south, which was 216 acres (87 ha) of the Martin Ranch called The Point. | .jpg.webp) |

[41] |

| 1923 | The Bank of Carmel opened on July 15, 1923, in a building between Mission and Dolores Streets in Carmel-by-the-Sea. Businessman Thomas Albert Work (1870–1963), of Pacific Grove, was elected president and Barnet J. Segal (1898–1985) was a director and early founder of the bank. |  |

[19] |

| 1925 | Paul Aiken Flanders founded the Carmel Land Company to help develop Hatton Fields. He purchased 233.15 acres (94.35 ha) of property from the Hatton estate for $100,000 (equivalent to $1,668,691 in 2022). The new company formed an office in a stucco building on Ocean Avenue between Louis S. Slevin's general merchandise store and the Carmel Bakery. Paul Flanders was president, Ernest Schweninger was secretary and sales manager, and Peter Mawdsley was the treasurer. |  |

[42][43] |

| 1926 | Frank B. Porter was a pioneer businessman and real estate developer of Monterey Peninsula. In 1926, he launched the first residential subdivision in Carmel Valley, California that became Robles del Rio, California (Spanish: Robles del Río, meaning "Oaks of the River"). Porter went on to develop other properties in the valley including the Robles del Rio Lodge, Robles del Rio Carmelo Water Company, and the Hatton Ranch (once the Rancho Cañada de la Segunda) in Carmel Valley. |  |

[5][14] |

| 1926 | The Tuck Box is a historic Craftsman Fairy tale commercial building is built in 1926, by master builder Hugh W. Comstock. In the early 1930s, the shop was known as "Sally's" tea room. |  |

[44] |

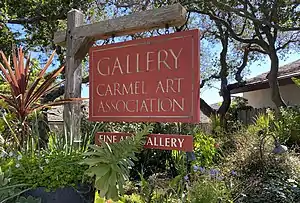

| 1927 | The Carmel Art Association was founded on August 8, 1927, by a small group of artists. Ira Mallory Remsen's studio on Dolores Street became the permanent home for the Carmel Art Association in 1933. Remsen had produced the plays Inchling and Mr. Bunt at the Forest Theater. |  |

[45] |

| 1927 | Carmel's business district continues to grow. The Carmel Weavers Studio, also known as Cottage of Sweets, was Ruth Kuster's weavers studio, that was in front of the Theatre of the Golden Bough. |  |

[46] |

| 1928 | The Harrison Memorial Library was designed by architect Bernard Maybeck and built by Michael J. Murphy in 1928. |  |

[47] |

| 1928 | The Kocher Building was the first of three commercial structures designed by Blaine & Olsen of Oakland, in the Spanish Eclectic Revival style. It was followed by El Paseo Building (1928) and La Ribera Hotel (1929). |  |

[19] |

| 1929 | The Grace Deere Velie Metabolic Clinic, funded by Grace Deere Velie Harris, opens on the outskirts of Carmel. Specializing in "metabolic disorders" it was converted to a general hospital in 1934 and becomes the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula. | [48] | |

| 1929 | Perry Newberry ran for office of the city trustee on the platform "Keep Carmel Off the Map!" |  |

[5]: p247 |

| 1929 | In early 1929 photographer Edward Weston moved to Johan Hagemeyer's cottage in Carmel, at Mountain View and Ocean Avenues. It was there that Weston finally found the solitude and the inspiration that he was seeking. |  |

[49] |

| 1932 | James Cooper Doud established the Doud Building, built by master builder Michael J. Murphy as a mixed-use retail shop and residence, located on the SW corner of Ocean Avenue and Mission Street. The cost of the building was $6,300 (equivalent to $135,127 in 2022). |  |

[50] |

| 1932 | Henry F. Dickinson established the Henry Dickinson House, built by master builder Michael J. Murphy as a two-story American Craftsman-style residence with a sloping shake roof, located at 26363 Isabella Avenue. |  |

[51] |

| 1937 | The Carmel Fire Station is located on 6th Avenue, between San Carolos and Mission Streets. The station was built in 1936-1937 and opened in June 1937. |  |

[52] |

| 1942 | During World War II the American Legion Post No. 512 operated as a USO club. In November 1941 alone, it served more than 1,350 soldiers from Fort Ord. In 1943, the USO Club added another extension to create a U-shaped building and added classes for servicemen and women in arts and crafts. |  |

[53][10] |

| 1948 | The Mrs. Clinton Walker House also known as Cabin on the Rocks, is located on Carmel Point in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. It has the appearance of a ship with a bow cutting through the waves. The house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1948 and completed in 1951 for Mrs. Clinton Della Walker of Pebble Beach. |  |

[54] |

| 1952 | Butterfly House, is a Mid-century modern house located on Carmel Point in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. Due to its unique wing-shaped roof, this building is commonly referred to as the Butterfly House. The house was designed and built by Francis W. Wynkoop. It is one of the few houses that are on the oceanfront at Carmel Point. |  |

[55] |

| 1986 | Actor Clint Eastwood, Republican is elected Mayor of Carmel from 1986 to 1988. |  |

[56] |

| 1989 | By 1989, the Harrison Memorial Library expanded to the a second Park Brank Library located at Mission Street and 6th Avenue. The Henry Meade Williams Local History Room, in honor of Henry Meade Williams, preserves collections of manuscripts, personal papers, photographs, and books relating to Carmel's history. |  |

[57] |

| 2020 | As of the 2020 census, the town had a total population of 3,220, down from 3,722 at the 2010 census. | [38] |

See also

References

- "Carmel-by-the-Sea, California – City Information, Fast Facts, Schools, Colleges, and More". www.citytowninfo.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- Temple, Sydney (March 1, 1987). Carmel-by-the-Sea: From Aborigines to Coastal Commission. Angel Press. ISBN 9780912216324.

- Slevin, Slevin, L.S., M. E. (1912). Guide Book to the Mission of San Carlos at Carmel and Monterey, California. Carmel News Co. pp. 9, 11. ASIN B000893QGS.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Elizabeth Barratt (May 2019). "The Meadows Tract" (PDF). Carmel Valley Voice. Carmel Valley, California. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- Fink, Augusta (2000). Monterey County: The Dramatic Story of its Past. Valley Publishers. p. 244. ISBN 9780913548622. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- "The U.S.-Mexican War . War (1846–1848). Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Randall, Frank Alfred. The History of Mission Ranch. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hudson, Monica (2006). Carmel-By-The-Sea. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 9–14. ISBN 9780738531229. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- "There were horses, cows and swine, but surprisingly, no sheep" (PDF). The Carmel Pine Cone. December 10, 2021. p. 23. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Dramov, Alissandra (2013). Carmel-By-The-Sea, the Early Years (1903–1913). ISBN 9781491824139. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "David Jacks". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California. November 21, 1873. p. 3. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- "David Jacks Passes Away". The Californian. Salinas, California. January 11, 1909. p. 1. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Orsi, Richard J. (February 6, 2007). Sunset Limited, The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West, 1850–1930. p. 115. ISBN 9780520251649. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hale, Sharron Lee (1980). A tribute to yesterday: The history of Carmel, Carmel Valley, Big Sur, Point Lobos, Carmelite Monastery, and Los Burros. Santa Cruz, California: Valley Publishers. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780913548738. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- "Carmel City. The Beautiful Spot Decided Upon For a Catholic Summer Resort". Monterey Cypress. Monterey, California. April 20, 1889. p. 1. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- "Old Bath House". Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea. August 6, 1945. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 881. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- Dramov, Alissandra (2022). Past & Present Carmel-By-The-Sea. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 9781467108980. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- Seavey, Kent (2007). Carmel, A History in Architecture. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780738547053. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grimes, Teresa; Heumann, Leslie. "Historic Context Statement Carmel-by-the-Sea" (PDF). Leslie Heumann and Associates1994. pp. 15–16. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- Kent L. Seavey (May 20, 2002). "Department Of Parks And Recreation" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- "Carmel-By-The-Sea". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California. April 26, 1903. p. 37. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- "The Carmel Monterey Peninsula Art Colony: A History by Barbara J. Klein". www.tfaoi.com. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- Dramov, Alissandra (2019). Historic Buildings of Downtown Carmel-by-the-Sea. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Arcadia Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781467103039. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- Neal Hotelling (June 24, 2021). "Professional historians refuse to settle for half-baked legends" (PDF). Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. pp. 27–28. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- "George Reamer, Pioneer, Dies". Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. November 25, 1938. p. 10. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- Pajka, Sharon (2021). Women Writers Buried in Virginia. p. 222. ISBN 9781467150668. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Connie Wright (2014). Stories of Old Carmel: A Centennial Tribute From The Carmel Residents Association.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "DANIEL T. MACDOUGAL (1865–1958)". dpb.carnegiescience.edu. 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 49, 124, 144, 179. ISBN 9781467545679. OCLC 1240419876.

- "20th-Century California Photographers". Pat Hathaway Photo Collection. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- "The Chase School Of Art At Carmel-By-The-Sea, California, by Eunice T. Gray". Art and Progress. 6 (4): 118–120. February 1915. JSTOR 20561363.

- Claudia Street (February 4, 1965). "Those Who Were Here In 1915 Recall Their Happy Memories". Carmel Pine cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- "1915 Oakland Tribute reference to founding of Carmel Pine Cone in 1915 by William Overstreet - Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- "S. F. B. Morse". The San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, California. January 15, 1916. p. 7. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "Fog Makes Fleet Late In Reaching Monterey Harbor". Bakersfield Morning Echo. Bakersfield, California. August 26, 1919. p. 2. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- Neal Hotelling (May 13, 2022). "A beloved library was named for someone who never lived there" (PDF). Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. p. 27. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Carmel Ball League Is Now Incorporated". The Californian. Salinas, California. September 8, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- "Abalone League Village Focal Point for Years". Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. April 19, 1940. p. 7. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- "Outlands In The Eighty Acres". United States Department of Interior National Park Service. February 21, 1989. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- "How the high school got there" (PDF). Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel, California. November 26, 2021. p. 22. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- "Property Transactions". Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. December 12, 1925. p. 12. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- Richard N. Janick (October 8, 2002). "Department Of Parks And Recreation" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- "Carmel Art Body Forms". Oakland Tribune. August 10, 1927. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- "Ocean Avenue to Have Another New Building". Monterey Daily Cypress and Monterey American. Monterey, California. September 13, 1922. p. 1. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- Kent L. Seavey (November 18, 2002). "Department Of Parks And Recreation" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- "Stanford, Clinic May Affiliate In Research". The Carmel Pine Cone. October 25, 1929. p. 1. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 193, 203–204, 222, 226, 241, 599, 618, 680, 689. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website ("Introduction to Online Presentation". Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.).

- Dramov, Alissandra (2019). Historic Buildings of Downtown Carmel-by-the-Sea. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 45, 85, 92. ISBN 9781467103039. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- Dramov, Alissandra; Momboisse, Lynn A. (2016). Historic Homes and Inns of Carmel-by-the-Sea. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Arcadia Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 9781467115971. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- Kent L. Seavey (April 25, 2002). "Department Of Parks And Recreation" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- "Long used by service members and veterans, buildings needs TLC" (PDF). The Carmel Pine Cone. November 12, 2021. p. 23. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- MALLOY, BETSY (June 26, 2019). "Mrs. Clinton Walker House by Frank Lloyd Wright". www.tripsavvy.com. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- Morgan, Mallery Roberts (May 25, 2018). AD Goes Inside Carmel's Iconic Butterfly House.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Call it "Clintwood-by-the-sea"". The Californian. Salinas, California. April 9, 1986. p. 1. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- "Monterey County Local Historical Directory of Archives and Resources". Monterey County Free Libraries. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carmel-by-the-Sea, California.

- Digital Public Library of America with items related to Carmel-by-the-Sea, California

- History Timeline of Carmel-by-the-Sea

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.