Poetry in The Lord of the Rings

The poetry in The Lord of the Rings consists of the poems and songs written by J. R. R. Tolkien, interspersed with the prose of his high fantasy novel of Middle-earth, The Lord of the Rings. The book contains over 60 pieces of verse of many kinds; some poems related to the book were published separately. Seven of Tolkien's songs, all but one from The Lord of the Rings, were made into a song-cycle, The Road Goes Ever On, set to music by Donald Swann. All the poems in The Lord of the Rings were set to music and published on CDs by The Tolkien Ensemble.

The verse is of many kinds, including for wandering, marching to war, drinking, and having a bath; narrating ancient myths, riddles, prophecies, and magical incantations; of praise and lament (elegy). Some of these forms were found in Old English poetry. Tolkien stated that all his poems and songs were dramatic in function, not seeking to express the poet's emotions, but throwing light on the characters, such as Bilbo Baggins, Sam Gamgee, and Aragorn, who sing or recite them.

Commentators have noted that Tolkien's verse has long been overlooked, and never emulated by other fantasy writers; but that since the 1990s it has received scholarly attention. The verse includes light-hearted songs and apparent nonsense, as with those of Tom Bombadil; the poetry of the Shire, which has been said to convey a sense of "mythic timelessness";[1] and the laments of the Riders of Rohan, which echo the oral tradition of Old English poetry.[2] Scholarly analysis of Tolkien's verse shows that it is both varied and of high technical skill, making use of different metres and rarely-used poetic devices to achieve its effects.

Embedded poetry

Supplementing narrative

The narrative of The Lord of the Rings is supplemented throughout by verse, in the form of over 60 poems and songs. Thomas Kullmann, a scholar of English literature, notes that this was unconventional for 20th century novels. The verses include songs of many genres: for wandering, marching to war, drinking, and having a bath; narrating ancient myths, riddles, prophecies, and magical incantations; of praise and lament (elegy). Kullman states that some, such as riddles, charms, elegies, and narrating heroic actions are found in Old English poetry.[3]

Michael Drout, a Tolkien scholar and encyclopedist, wrote that most of his students admitted to skipping the poems when reading The Lord of the Rings, something that Tolkien was aware of.[4] Tolkien stated that his verse differed from conventional modern poetry which aimed to express the poet's emotions: "the verses in [The Lord of the Rings] are all dramatic: they do not express the poor old professor's soul searchings, but are fitted in style and contents to the characters in the story that sing or recite them, and to the situations in it".[T 1] The Tolkien scholar Andrew Higgins wrote that Drout had made a "compelling case" for studying it. The poetry was, Drout wrote, essential for the fiction to work aesthetically and thematically; it added information not given in the prose; and it brought out characters and their backgrounds. Another Tolkien scholar, Allan Turner, suggested that Tolkien may have learnt the method of embedding multiple types of verse into a text from William Morris's The Life and Death of Jason, possibly, Turner suggests, the model for Tolkien's projected Tale of Earendel.[4]

Brian Rosebury, a scholar of humanities, writes that the distinctive thing about Tolkien's verse is its "individuation of poetic styles to suit the expressive needs of a given character or narrative moment",[5] giving as examples of its diversity the "bleak incantation" of the Barrow-Wight; Gollum's "comic-funereal rhythm" in The cold hard lands / They bites our hands; the Marching Song of the Ents; the celebratory psalm of the Eagles; the hymns of the Elves; the chants of the Dwarves; the "song-speech" of Tom Bombadil; and the Hobbits' diverse songs, "variously comic and ruminative and joyful".[5]

Integral to story

Diane Marchesani, in Mythlore, considers the songs in The Lord of the Rings as "the folklore of Middle-earth", calling them "an integral part of the narrative".[6] She distinguishes four kinds of folklore: lore, including rhymes of lore, spells, and prophecies; ballads, from the Elvish "Tale of Tinuviel" to "The Ent and the Entwife" with its traditional question-answer format; ballad-style, simpler verse such as the hobbits' walking-songs; and nonsense, from "The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late" to Pippin's "Bath Song". In each case, she states, the verse is "indispensable" to the narrative, revealing both the characters involved and the traditions of their race.[6]

Sandra Ballif Straubhaar, a scholar of Germanic studies, writes that the narrative of The Lord of The Rings is composed of both prose and poetry, "intended and constructed to flow complementarily as an integrated whole."[7] The verse, therefore, is "an indispensable part of the narrative itself".[7] It may, she states, provide backstory, as with Aragorn's "Lay of Lúthien" or Bilbo's song of Eärendil, or it may enrich or advance the plot, as with Sam Gamgee's unprompted prayer to the Lady of the Stars, Elbereth, at a dark moment in the Tower of Cirith Ungol, or Gilraen's farewell linnod to her son Aragorn.[7] The linnod, her last words to Aragorn, was:

- Ónen i-Estel Edain, ú-chebin estel anim[T 2]

translated as "I gave Hope [Estel being one of Aragorn's names] to the Dúnedain [her people], I have kept no hope for myself."[T 2] Straubhaar writes that although the reader does not know why Gilraen should suddenly switch to speaking in verse, one can feel the tension as she adopts "high speech, .. formalized patterns, .. what Icelanders even today call bundidh mál, "bound language."[7]

Functions

"Shire-poetry"

A strand of Tolkien's Middle-earth verse is what the Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey calls "Shire-poetry": "plain, simple, straightforward in theme and expression", verse suitable for hobbits, but which turns out to vary continuously to suit changing situations and growing characters.[1] The poetry of the Shire serves, in Shippey's view, to relate the here-and-now action of the story to "mythic timelessness", as in Bilbo's Old Walking Song, "The Road goes ever on and on / Down from the door where it began. Now far ahead the Road has gone, And I must follow, if I can, Pursuing it with eager feet...", at the start of The Lord of the Rings. The poem reappears, this time sung by Frodo, varied with "weary feet" to suit his mood, shortly before he sees a Ringwraith; and a third time, at the end of the book, by a much aged, sleepy, forgetful, dying Bilbo in Rivendell, when the poem has shifted register to "But I at last with weary feet / Will turn towards the lighted inn, My evening-rest and sleep to meet". Shippey observes that the reader can see that while Bilbo is indeed sleepy, the subject is now death. Frodo, too, leaves Middle-earth, but with a different walking-song, singing of "A day will come at last when I / Shall take the hidden paths that run / West of the Moon, East of the Sun", which Shippey glosses as the "Lost Straight Road" that goes out of the round world, straight to Elvenhome.[1]

Shippey writes that Shakespeare, too, could write Shire-poetry. Bilbo's "When winter first begins to bite" is certainly, Shippey states, a rewrite of Shakespeare's Shire-poem to winter in Love's Labours Lost, a token of Tolkien's guarded respect (as he disliked much of Shakespeare's handling of myth, legend, and magic) and even "a sort of fellow-feeling":[8]

| Shakespeare Love's Labours Lost, Act 5, scene 2 | Bilbo Baggins's poem in "The Ring goes South"[T 3] |

|---|---|

| When icicles hang by the wall, And Dick the shepherd blows his nail, And Tom bears logs into the hall, And milk comes frozen home in pail, When blood is nipped, and ways be foul, Then nightly sings the staring owl... | When winter first begins to bite and stones crack in the frosty night, when pools are black and trees are bare, 'tis evil in the Wild to fare. |

"Nonsense"

Lynn Forest-Hill, a medievalist, explores what Tolkien called "nonsense" and "a long string of nonsense-words (or so they seemed)", namely Tom Bombadil's constant metrical chattering, in the style of "Hey dol! merry dol! ring a ding dillo! / Ring a dong! hop along! fa la the willow! / Tom Bom, jolly Tom, Tom Bombadillo!".[T 4] She states at once that "The parenthetical qualification immediately questions any hasty assumption that the song is indeed mere 'nonsense'." Instead, she writes, the seemingly strange and incongruous challenges the reader to engage with the text.[9] Rebecca Ankeny, a scholar of English, states that Tom Bombadil's nonsense indicates that he is benign, but also irrelevant as he could not be trusted to keep the Ring safe: he'd simply forget it.[10] One aspect, Forest-Hill notes, is Tom Bombadil's ability to control his world with song (recalling the hero Väinämöinen in the Finnish epic, the Kalevala[11]), however apparently nonsensical. Another is the fact that he only speaks in metre:[9][11]

Whoa! Whoa! steady there! ...

where be you a-going to,

puffing like a bellows? ...

I'm Tom Bombadil.

Tell me what's your trouble!

Tom's in a hurry now.

Don't you crush my lilies!— A sample of Tom Bombadil's speech[T 4]

The Tolkien scholar David Dettmann writes that Tom Bombadil's guests also find that song and speech run together in his house; they realize they are all "singing merrily, as if it was easier and more natural than talking".[11][T 5] As with those who heard Väinämöinen, listening all day and wondering at their pleasure,[12] the hobbits even forget their midday meal as they listen to Tom Bombadil's stories and songs of nature and local history.[11] All these signals are, Forest-Hill asserts, cues to the reader to look for Tolkien's theories of "creativity, identity, and meaning".[9]

Apparent silliness is not confined to Tom Bombadil. Ankeny writes that the change in the hobbits' abilities with verse, starting with silly rhymes and moving to Bilbo's "translations of ancient epics", signals their moral and political growth. Other poems inset in the prose give pleasure to readers by reminding them of childish pleasures, such as fairy tales or children's stories.[10]

Oral tradition

Shippey states that in The Lord of the Rings, poetry is used to give a direct impression of the oral tradition of the Riders of Rohan. He writes that "Where now the horse and the rider?" echoes the Old English poem The Wanderer; that "Arise now, arise, Riders of Theoden" is based on the Finnesburg Fragment, on which Tolkien wrote a commentary; and that there are three other elegiac poems. All of these are strictly composed in the metre of Old English verse. In Shippey's opinion, these poems have the same purpose "as the spears that the Riders plant in memory of the fallen, as the mounds that they raise over them, as the flowers that grow on the mounds": they are about memory "of the barbarian past",[2] and the fragility of oral tradition makes what is remembered specially valuable. As fiction, he writes, Tolkien's "imaginative re-creation of the past adds to it an unusual emotional depth."[2]

Mark Hall, a Tolkien scholar, writes that Tolkien was strongly influenced by old English imagery and tradition, most clearly in his verse. The 2276 lines of the unfinished "Lay of the Children of Hurin"[T 6] present in Christopher Tolkien's words a "sustained embodiment of his abiding love of the resonance and richness of sound that might be achieved in the ancient English metre". The poem is in alliterative verse (unlike Tolkien's second version which is in rhyming couplets). Hall calls this "bringing forward to modern readers the ideas of the ancient poets, [and their] style and atmosphere", using rhythm, metre, and alliteration to convey the "style and mood" of Old English. Among the examples he gives is Aragorn's lament for Boromir, which he compares to Scyld Scefing's ship-burial in Beowulf:[13]

| Beowulf 2:36b–42 Scyld Scefing's funeral | Hall's Translation | "Lament for Boromir"[T 7] (floated in a boat down the Anduin to the Falls of Rauros) |

|---|---|---|

| þær wæs madma fela of feorwegum frætwa gelæded; ne hyrde ic cymlicor ceol gegyrwan hildewæpnum ond heaðowædum, billum ond byrnum; him on bearme læg madma mænigo, þa him mid scoldon on flodes æht feor gewitan. |

There was much treasure from faraway ornaments brought not heard I of more nobly a ship prepared war-weapons and war-armour sword and mail; on his lap lay treasures many then with him should on floods' possession far departed. |

'Beneath Amon Hen I heard his cry. There many foes he fought. His cloven shield, his broken sword, they to the water brought. His head so proud, his face so fair, his limbs they laid to rest; And Rauros, golden Rauros-falls, bore him upon its breast.' |

Hall finds further resemblances: between Tolkien's "The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son" and "The Battle of Maldon"; and between the lament of "The Mounds of Mundburg" to "The Battle of Brunanburh".[13] In Shippey's view, the three epitaph poems in The Lord of the Rings, including "The Mounds of Mundburg" and, based on the famous Ubi sunt? passage in "The Wanderer", Tolkien's "Lament of the Rohirrim",[4][14][15] represent Tolkien's finest alliterative Modern English verse:[4]

| The Wanderer 92–96 | Translation | Lament of the Rohirrim[T 8] |

|---|---|---|

| Hwær cwom mearg? Hwær cwom mago? Hwær cwom maþþumgyfa? Hwær cwom symbla gesetu? Hwær sindon seledreamas? Eala beorht bune! Eala byrnwiga! Eala þeodnes þrym! Hu seo þrag gewat, genap under nihthelm, swa heo no wære. |

Where is the horse? where the rider? Where the giver of treasure? Where are the seats at the feast? Where are the revels in the hall? Alas for the bright cup! Alas for the mailed warrior! Alas for the splendour of the prince! How that time has passed away, dark under the cover of night, as if it had never been. |

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing? Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing? Where is the hand on the harp-string, and the red fire glowing? Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing? They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow; ... |

"Thus spoke a forgotten poet long ago in Rohan, recalling how tall and fair was Eorl the Young, who rode down out of the North," Aragorn explains, after singing the Lament.[T 8]

Glimpses of another world

When the hobbits have reached the safe and ancient house of Elrond Half-Elven in Rivendell, Tolkien uses a poem and a language, in Shippey's words, "in an extremely peculiar, idiosyncratic and daring way, which takes no account at all of predictable reader-reaction":[16][T 9]

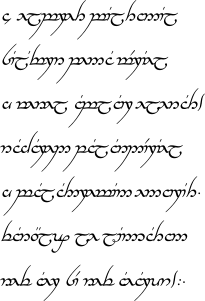

| Tengwar | Transcribed |

|---|---|

|

A Elbereth Gilthoniel

|

The verse is not translated in the chapter, though it is described: "the sweet syllables of the elvish song fell like clear jewels of blended word and melody. 'It is a song to Elbereth', said Bilbo", and at the very end of the chapter there is a hint as to its meaning: "Good night! I'll take a walk, I think, and look at the stars of Elbereth in the garden. Sleep well!"[16][T 9] A translation of the Sindarin appeared much later, in the song-cycle The Road Goes Ever On;[T 10] it begins "O Elbereth who lit the stars". Readers, then, were not expected to know the song's literal meaning, but they were meant to make something of it: as Shippey says, it is clearly something from an unfamiliar language, and it announces that "there is more to Middle-earth than can immediately be communicated".[16] In addition, Tolkien believed, contrary to most of his contemporaries, that the sounds of language gave a specific pleasure that the listener could perceive as beauty; he personally found the sounds of Gothic and Finnish, and to some extent also of Welsh, immediately beautiful. In short, as Shippey writes, Tolkien "believed that untranslated elvish would do a job that English could not".[16] Shippey suggests that readers do take something important from a song in another language, namely the feeling or style that it conveys, even if "it escapes a cerebral focus".[16]

Signalling power and the Romantic mode

Ankeny writes that several of Tolkien's characters exercise power through song, from the primordial creative music of the Ainur, to the song-battle between Finrod and the Dark Lord Sauron, Lúthien's song in front of Sauron's gates, or the singing of the Rohirrim as they killed orcs in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Ankeny states that the many poems in the text of Lord of the Rings, through their contexts and content "create a complex system of signs that add to the basic narrative in various ways".[10] The insetting of poems in a larger work is reminiscent, too, of Beowulf, and, she writes, indicates Tolkien's depth of "involvement with the literary tradition".[10]

The presence of the rhyme of the Rings on the frontispiece of each volume indicates, Ankeny writes, that the threat persists past the first volume, where the rhyme is repeated three times, causing horror in Rivendell when Gandalf says it aloud, and in the Black Speech rather than English. Further, as the threat from Sauron grows, the number of inset poems and songs diminishes. The literary genre is signalled as what Northrop Frye classifies as Romance by the way the Elvish songs speak of fading away. This mirrors what the Elves know is their own imminent passing, while the number of songs of Men increases. The Anglo-Saxon style verse and language of the Rohirrim adds a feeling of real historical depth, and that, Ankeny suggests, flows over into a feeling of verisimilitude for the invented Elvish languages also.[10] Kullmann states that the wizard Gandalf demonstrates his competence as a wizard through his philological skill with the verse of the Rings, and that readers too are given a philological insight into the history of a poem "and the story told by this history".[3]

Technical skill

A mixed reception

In the early 1990s, the scholar of English Melanie Rawls wrote that while some critics found Tolkien's poetry, in The Lord of the Rings and more generally, "well-crafted and beautiful", others thought it "excruciatingly bad."[17] The Scottish poet Alan Bold,[18] cited by Rawls, similarly did "not think much of Tolkien's poetry as poetry."[10] Granting that since his Middle-earth books were not written "in the style of a modern novel", modern verse would have been totally inappropriate, Rawls attacked his verse with phrases such as "weighed down with cliches and self-consciously decorative words", concluding "He was a better writer of prose than of verse."[17] On the other hand, Geoffrey Russom, a scholar of Old and Middle English verse, considered Tolkien's varied verse as constructing "good music", with a rich diversity of structure that avoids the standard iambic pentameter of much modern English poetry.[19] The scholar of English Randel Helms described Tolkien's "Errantry" as "a stunningly skillful piece of versification ... with smooth and lovely rhythms";[20] and Ankeny writes that Tolkien's poetry "reflects and supports Tolkien's notion of Secondary Creation".[10] Shippey writes that while Tolkien has been imitated by many fantasy authors, none have tried to emulate his use of poems scattered throughout his novels. He gives two possible reasons for this: it might just be too much trouble; but he suggests that the main reason is that Tolkien was professionally trained as a philologist to investigate the complexities of literary tradition, complete with gaps, mistakes, and contradictory narratives. Since the discipline has disappeared, Shippey argues that it is probable no author will ever attempt it again,[21] as indeed Tolkien implied in a letter.[T 11]

Metrical originality

| Disyllables | |

|---|---|

| ◡ ◡ | pyrrhic, dibrach |

| ◡ – | iamb |

| – ◡ | trochee, choree |

| – – | spondee |

| Trisyllables | |

| ◡ ◡ ◡ | tribrach |

| – ◡ ◡ | dactyl |

| ◡ – ◡ | amphibrach |

| ◡ ◡ – | anapaest, antidactylus |

| ◡ – – | bacchius |

| – – ◡ | antibacchius |

| – ◡ – | cretic, amphimacer |

| – – – | molossus |

| See main article for tetrasyllables. | |

In a detailed reply to Rawls, the poet Paul Edwin Zimmer wrote that "much of the power of Tolkien's 'prose' comes from the fact that it's written by a poet of high technical skill, who carried his metrical training into his fiction."[22] Zimmer gave as an example the fact that the whole of Tom Bombadil's dialogue, not only the parts set out as verse, are in a metre "built on amphibrachs and amphimacers, two of the most obscure and seldom-seen tools in the poet's workshop." Thus (stresses marked with "`", feet marked with "|"):[22]

- `Old `Tom | `Bom-ba-`dil | `was a `mer- | -ry `fel-low

consists of a spondee, two amphimacers, and an amphibrach: and, Zimmer wrote, Tolkien varies this pattern with what he called "metrical tricks" such as ambiguous stresses. Another "chosen at random from hundreds of possible examples" is Tolkien's descriptive and metrical imitation, in prose, of the different rhythms of running horses and wolves:[22]

- `Horse-men were | `gal-lop-ing | on the `grass | of Ro-`han | `wolves `poured | `from `Is-en-`gard.

Zimmer marked this as "dactyl, dactyl, anapaest, anapaest for the galloping riders; the sudden spondee of the wolves".[22]

In Zimmer's view, Tolkien could control both simple and complex metres well, and displayed plenty of originality in the metres of poems such as "Tom Bombadil" and "Eärendil".[22]

The effect of song

The medievalists Stuart D. Lee and Elizabeth Solopova analyzed Tolkien's poetry, identifying the skill of its construction. They noted that some of his verse is written in iambic tetrameters, four feet each of an unstressed and a stressed syllable: a common format in Modern English. They stated that Tolkien often fits his verse to the metre very carefully, where the English tradition as seen in Shakespeare's sonnets is for a looser fit. Tolkien emphasizes the rhythm in the song "Under the Mountain dark and tall" by the repeated use of the same syntactic construction; this would, they wrote, be seen as monotonous in a poem, but in a song it gives the effect of reciting and singing, in this case as Thorin Oakenshield's Dwarves prepare for battle in their mountain hall:[23]

- The `sword | is `sharp, | the `spear | is `long,

- The `ar- | -row `swift, | the `Gate | is `strong;

- from "Under the Mountain dark and tall"[T 12]

Alliterative verse

At other times, to suit the context of events like the death of King Théoden, Tolkien wrote what he called "the strictest form of Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse".[T 13] That strict form means that each line consists of two half-lines, each with two stresses, separated by a caesura, a rhythmic break. Alliteration is not constant, but is common on the first three stressed syllables within a line, sometimes continuing across several lines: the last stressed syllable does not alliterate. Names are constantly varied: in this example, the fallen King of the Rohirrim is named as Théoden, and described as Thengling and "high lord of the host". Lee and Solopova noted that in that style, unlike in Modern English poetry, sentences can end mid-line:[23]

- We `heard of the `horns in the `hills `ringing,

- the `swords `shining in the `South-`kingdom.

- `Steeds went `striding to the `Stoning`land

- as `wind in the `morning. `War was `kindled.

- There `Théoden `fell, `Thengling `mighty,

- to his `golden `halls and `green `pastures

- in the `Northern `fields `never `returning,

- `high lord of the `host.

- from "The Mounds of Mundburg"[T 14]

An Elvish effect

The longest poem in The Lord of the Rings is the Song of Eärendil which Bilbo sings at Rivendell. Eärendil was half-elven, embodying both mortal Man and immortal Elf. Shippey writes that the work exemplifies "an elvish streak .. signalled .. by barely-precedented intricacies" of poetry. He notes however that the "elvish tradition" corresponded to a real English tradition, that of the Middle English poem Pearl. That poem makes use of an attempt at immortality and a "fantastically complex metrical scheme" with many poetic mechanisms, including alliteration as well as rhyme; for example, it begins "Perle, plesaunte to prynces paye / To clanly clos in golde so clere".[24] Shippey observes that the tradition of such complex verse had died out before the time of Shakespeare and Milton, to their and their readers' loss, and that "Tolkien obviously hoped in one way to recreate it," just as he sought to create a substitute for the lost English mythology.[25]

Shippey identifies five mechanisms Tolkien used in the poem to convey an "elvish" feeling of "rich and continuous uncertainty, a pattern forever being glimpsed but never quite grasped", its goals "romanticism, multitudinousness, imperfect comprehension .. achieved stylistically much more than semantically." The mechanisms are rhyme, internal half-rhyme, alliteration, alliterative assonance, and "a frequent if irregular variation of syntax." They can be seen in the first stanza of the long poem, only some of the instances being highlighted:[25]

| Line | Song of Eärendil[T 9] Stanza 1: building his ship | Poetic mechanisms identified by Tom Shippey[25] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eärendil was a mariner | Internal half-rhyme with 2 |

| 2 | that tarried in Arvernien; | Rhymes with 4 (intentionally imperfect) |

| 3 | he built a boat of timber felled | Alliteration, and possible assonance Internal half-rhyme with 4 |

| 4 | in Nimbrethil to journey in; | |

| 5 | her sails he wove of silver fair, | Alliterative assonance Grammatical repetitions and variations |

| 6 | of silver were her lanterns made, | Grammatical repetitions and variations Rhymes with 8 |

| 7 | her prow was fashioned like a swan, | |

| 8 | and light upon her banners laid. | Alliteration |

Settings

.jpg.webp)

Seven of Tolkien's songs (all but one, "Errantry", from The Lord of the Rings) were made into a song-cycle, The Road Goes Ever On, set to music by Donald Swann in 1967.[27]

Bilbo's Last Song, a kind of pendant to Lord of the Rings, sung by Bilbo as he leaves Middle-earth for ever, was set to music by Swann and added to the second (1978) and third (2002) editions of The Road Goes Ever On.[T 15][28]

A Danish group of musicians, The Tolkien Ensemble, founded in 1995, set all the poetry in The Lord of the Rings to music, publishing it on four CDs between 1997 and 2005. The project was approved by the Tolkien family and the publishers, HarperCollins. Drawings by Queen Margrethe II of Denmark were used to illustrate the CDs.[26] The settings were well received by critics.[29][30]

Much of the music in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film series is non-diegetic (not heard by the characters), so few of Tolkien's songs are performed. Aragorn sings a few lines of the "Lay of Lúthien", a cappella, in Elvish. Éowyn is heard singing a little of a "Lament for Théodred" in Old English, but the words are not Tolkien's.[31][32] "The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late" is not sung in The Prancing Pony,[33] but in the extended edition of Jackson's 2012 film The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, the Dwarf Bofur sings it at Elrond's feast in Rivendell.[34]

Works

The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings contains 61 poems:[3]

- Book 1: 22 poems, including "The Road Goes Ever On and On" and "The Stone Troll"

- Book 2: 10 poems, including "Eärendil was a mariner" and "When winter first begins to bite"

- Book 3: 14 poems, including "Where now the horse and the rider?" and "A Rhyme of Lore"

- Book 4: 2 poems, including "Oliphaunt"

- Book 5: 6 poems, including "Arise, arise, Riders of Theoden!"

- Book 6: 7 poems, including "Upon the Hearth the Fire is Red"

Other works

The Hobbit contains over a dozen poems, many of which are frivolous, but some—like the dwarves' ballad in the first chapter, which is continued or adapted in later chapters—show how poetry and narrative can be combined.[35] The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, published in 1962, contains 16 poems including some such as "The Stone Troll" and "Oliphaunt" that also appear in The Lord of the Rings. The first two poems in the collection concern Tom Bombadil, a character described in The Fellowship of the Ring,[T 16] while "The Sea-Bell" or "Frodos Dreme" was considered by the poet W. H. Auden to be Tolkien's "finest" poetic work.[36] Bilbo's Last Song was published separately. While Shippey finds it mythically appropriate for the last words of a man dying contented with his life and achievements,[35] Rosebury finds it banal and inept, preferring "I sit beside the fire"[T 17] as Bilbo's swan song.[37]

See also

- The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, poems more or less connected to Middle-earth, three of them also in The Lord of the Rings

- Tolkien's prose style

References

Primary

- Carpenter 1981, #306 to Michael Tolkien, October 1968

- Tolkien 1955, Appendix A, "The Númenorean Kings", "The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 3 "The Ring goes South"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 6 "The Old Forest"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 7 "In the House of Tom Bombadil"

- Tolkien 1985, part 1, 1. "Lay of the Children of Hurin"

- Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 1 "The Departure of Boromir"

- Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 6 "The King of the Golden Hall"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 1 "Many Meetings"

- Tolkien & Swann 2002, p. 72

- Carpenter 1981, #238 to Jane Neave, 18 July 1962

- Tolkien 1937, chapter 15, "The Gathering of the Clouds"

- Carpenter 1981, #187 to H. Cotton Minchin, April 1956

- Tolkien 1955, book 5, chapter 6, "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- Tolkien 1990

- Tolkien 2014, pp. 35–54, 75, 88

- Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 3 "The Ring goes South"

Secondary

- Shippey 2001, pp. 188–191.

- Shippey 2001, pp. 96–97.

- Kullmann, Thomas (2013). "Poetic Insertions in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings". Connotations: A Journal for Critical Debate. 23 (2): 283–309. reviewing Eilmann & Turner 2013

- Higgins, Andrew (2014). "Tolkien's Poetry (2013), edited by Julian Eilmann and Allan Turner". Journal of Tolkien Research. 1 (1). Article 4.

- Rosebury 2003, p. 118.

- Marchesani 1980, pp. 3–5.

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2005). "Gilraen's Linnod : Function, Genre, Prototypes". Journal of Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 235–244. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0032. ISSN 1547-3163. S2CID 170378314.

- Shippey 2001, pp. 195–196.

- Forest-Hill, Lynn (2015). ""Hey dol, merry dol": Tom Bombadil's Nonsense, or Tolkien's Creative Uncertainty? A Response to Thomas Kullmann". Connotations. 25 (1): 91–107.

- Ankeny, Rebecca (2005). "Poem as Sign in 'The Lord of the Rings'". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 16 (2 (62)): 86–95. JSTOR 43308763.

- Dettmann, David L. (2014). John William Houghton; Janet Brennan Croft; Nancy Martsch (eds.). Väinämöinen in Middle-earth: The Pervasive Presence of the Kalevala in the Bombadil Chapters of 'The Lord of the Rings'. pp. 207–209. ISBN 978-1476614861.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kalevala, 44: 296

- Hall, Mark F. (2006). "The Theory and Practice of Alliterative Verse in the Work of J.R.R. Tolkien". Mythlore. 25 (1). Article 4.

- Shippey 2005, p. 202.

- Lee & Solopova 2005, pp. 47–48, 195–196.

- Shippey 2001, pp. 127–133.

- Rawls, Melanie A. (1993). "The Verse of J.R.R. Tolkien". Mythlore. 19 (1). Article 1.

- Bold, Alan (1983). "Hobbit Verse Versus Tolkien's Poem". In Giddings, Robert (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien: This Far Land. Vision Press. pp. 137–153. ISBN 978-0389203742.

- Russom, Geoffrey (2000). "Tolkien's Versecraft in 'The Hobbit' and 'The Lord of the Rings'". In Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel (eds.). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances. Greenwood Press. pp. 54–69. ISBN 9780313308451.

- Helms, Randel (1974). Tolkien's World. Thames and Hudson. p. 130. ISBN 978-0500011140.

- Shippey 2001, pp. 324–325.

- Zimmer, Paul Edwin (1993). "Another Opinion of 'The Verse of J.R.R. Tolkien'". Mythlore. 19 (2). Article 2.

- Lee & Solopova 2005, pp. 46–53.

- "Pearl". Pearl. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 217–221

- Drout, Michael D. C. (2006). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 539. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- "Song-Cycles". The Donald Swann Website. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Scull, Christina; Hammond, Wayne G. (2017). The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). HarperCollins. p. 1101. ISBN 978-0008214548.

- Weichmann, Christian. "The Lord of the Rings: Complete Songs and Poems (4-CD-Box)". The Tolkien Ensemble. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Snider, John C. (March 2003). "CD Review: At Dawn in Rivendell: Selected Songs & Poems from The Lord of the Rings by The Tolkien Ensemble & Christopher Lee". SciFiDimensions. Archived from the original on 19 October 2006. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Shehan, Emma (2017). Middle-Earth Soundscapes: An exploration of the sonic adaptation of Peter Jackson's 'The Lord of the Rings' through the lens of Dialogue, Music, Sound, and Silence (PDF). Carleton University, Ottawa (MA thesis in Music and Culture). pp. 57–80.

- Mathijs, Ernest (2006). The Lord of the Rings: Popular Culture in Global Context. Wallflower Press. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-1904764823.

- Canfield, Jared (13 March 2017). "The Lord Of The Rings: 15 Worst Changes From The Books To The Movies". ScreenRant. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

Without suggesting the trilogy be turned into a full-blown movie-musical, it would have benefited from Frodo's ditty in the Prancing Pony or Aragorn's poem about Gondor.

- "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey Extended Edition Scene Guide". The One Ring.net. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Shippey 2001, pp. 56–57.

- Auden, W. H. (2015). The Complete Works of W. H. Auden, Volume V: Prose: 1963–1968. Princeton University Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0691151717.

- Rosebury 2003, pp. 118–119.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Eilmann, Julian; Turner, Allan, eds. (2013). Tolkien's Poetry. Walking Tree. ISBN 978-3905703283.

- Marchesani, Diane (1980). "Tolkien's Lore: The Songs of Middle-earth". Mythlore. 7 (1): 3–5 (Article 1).

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137454690.

- Rosebury, Brian (2003). Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-59998-7.

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261104013.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1990) [1967]. Bilbo's Last Song. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-53810-6.

- Tolkien, J. R. R.; Swann, Donald (2002) [1968]. The Road Goes Ever On (3rd ed.). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-713655-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1985). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lays of Beleriand. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-39429-5.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2014) [1962]. The Adventures of Tom Bombadil: and other verses from the Red Book. London. ISBN 978-0-00-755727-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)