Tonopah, Nevada

Tonopah (/ˈtoʊnəˌpɑː/ TOHN-ə-pah, Shoshoni language: Tonampaa[4]) is an unincorporated town[5] in, and the county seat of, Nye County, Nevada, United States.[6] Nicknamed the Queen of the Silver Camps for its mining-rich history,[1] it is now primarily a tourism-based resort city, notable for attractions like the Mizpah Hotel and the Clown Motel.

Tonopah, Nevada | |

|---|---|

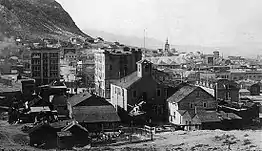

Central Tonopah from the south | |

| Nickname: Queen of the Silver Camps[1] | |

| Motto: Visit Today & Mine Away | |

Tonopah, Nevada, is located in the Tonopah Basin near the Esmeralda County border. | |

Tonopah Location of Tonopah in Nevada and the US  Tonopah Tonopah (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 38°4′2″N 117°13′48″W[2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Nye County |

| Founded | 1900 |

| Named for | Shoshoni language |

| Government | |

| • Senate | Scott Hammond (R) |

| • Assembly | Gregory Hafen II (R) |

| • U.S. Congress | Steven Horsford (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.26 sq mi (23.98 km2) |

| • Land | 9.26 sq mi (23.98 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 6,047 ft (1,843 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 2,179 |

| • Density | 235.34/sq mi (90.87/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 89049 |

| Area code | 775 |

| FIPS code | 32-73600 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0845985 |

| Website | http://www.tonopahnevada.com/ |

| Reference no. | 15 |

Tonopah is located at the junction of U.S. Routes 6 and 95, approximately midway between Las Vegas and Reno. In the 2010 census, the population was 2,478. The census-designated place (CDP) of Tonopah has a total area of 16.2 square miles (42 km2), all land.

History

The American community began circa 1900 with the discovery of silver-rich ore by prospector Jim Butler. The legendary tale of discovery says that he went looking for a burro that had wandered off during the night and sought shelter near a rock outcropping. When Butler discovered the animal the next morning, he picked up a rock to throw at it in frustration, noticing that the rock was unusually heavy. He had stumbled upon the second-richest silver strike in Nevada history.

Men of wealth and power entered the region to consolidate the mines and reinvest their profits into the infrastructure of the town of Tonopah. George Wingfield, a 24-year-old poker player when he arrived in Tonopah, played poker and dealt faro in the town saloons. Once he had a small bankroll, he talked Jack Carey, owner of the Tonopah Club, into taking him in as a partner and to file for a gaming license. In 1903, miners rioted against Chinese workers in Tonopah. This resulted in China enforcing a boycott in China of U.S. imported goods.

By 1904, after investing his winnings in the Boston-Tonopah Mining Company, Wingfield was worth $2 million. When old friend George S. Nixon, a banker, arrived in town, Wingfield invested in his Nye County Bank. They grub-staked (provided with food, supplies and tools in an exchange for a percentage of mine yield) miners with friend Nick Abelman, and bought existing mines. By the time the partners moved to Goldfield, Nevada and made their Goldfield Consolidated Mining Company a public corporation in 1906, Nixon and Wingfield were worth more than $30 million.[7]

Wingfield believed that the end of the gold and silver mining production was coming and took his bankroll to Reno, where he invested heavily in real estate and casinos. Real estate and gaming became big business throughout Central Nevada. By 1910, gold production was falling and by 1920, the town of Tonopah had less than half the population it had fifteen years earlier.

Small mining ventures continued to provide income for local miners and the small town struggled on. Located about halfway between Reno and Las Vegas, it has supported travelers as a stopover and rest spot on a lonely highway. Today the Tonopah Station has slots and the Banc Club also offers some gaming.

Also in Nye County is the Yomba Band of the Yomba Shoshone Tribe of the Yomba Reservation, a federally recognized band of Western Shoshone people. The Western Shoshone dominated most of Nevada at the time of American settlement in the 1860s.

Since the late 20th century, Tonopah has relied on the nearby military Tonopah Test Range as its main source of employment. The military has used the range and surrounding areas as a nuclear bomb test site, a bombing range, and as a base of operations for the development of the F-117 Nighthawk.

In 2014, California-based solar energy company SolarReserve completed construction on a $980 million advanced solar energy project near Tonopah. The Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project uses liquid sodium as a heat transfer medium for its solar energy storage technology. The plant began producing power in November 2015.[8][9]

On May 15, 2020, a magnitude 6.5 earthquake struck 35 miles (56 km)[10] west of Tonopah, followed by a series of aftershocks, the largest of which was a magnitude 5.1. However, no injuries were reported. It was the largest earthquake in Nevada since 1954.[11]

Etymology and pronunciation

The founder, Jim Butler, named the settlement from what is thought to be a Shoshoni language word, pronounced "TOE-nuh-pah."[12] Although the town previously had a variety of names, including Butler City, Jim Butler's name has survived. According to local history, the name is said to mean "hidden spring".[1]

Linguistically, the name derives from either Shoshone to-nuv (greasewood), or Northern Paiute to-nav (greasewood), and pa, meaning water in both dialects.[13]

Climate

Tonopah has an arid, cold desert climate with cool winters and hot summers. Due to Tonopah’s aridity and high altitude, daily temperature ranges are quite large and lows in winter are similar to many continental climates. Nights are cool, even in summer.

There are an average of 50.3 afternoons with highs at or above 90 °F or 32.2 °C, 157.8 mornings with lows of 32 °F (0 °C) or lower, 7.6 afternoons where the high does not top freezing and 1.7 mornings with lows below 0 °F or −17.8 °C. The record high temperature in Tonopah was 104 °F (40 °C) on July 18, 1960, and the record low −15 °F (−26.1 °C) on January 24, 1937 and January 23, 1962.

There are an average of 38 days with measurable precipitation and about 5.14 inches (130.6 mm) of precipitation that falls each year. The amount of minimal precipitation that does fall is roughly the same for each month at about 0.3 inches (7.6 mm) to 0.5 inches (12.7 mm) per month. The wettest calendar year was 1978 with 10.64 in (270 mm) and the driest 2020 with 1.95 in (50 mm). The most precipitation in one month was 3.46 inches (87.9 mm) in August 2023. The most precipitation in 24 hours was 2.55 inches (64.8 mm) on August 20, 2023. Average annual snowfall is 16.8 inches or 0.43 metres, though even in winter the median snow depth is zero and the maximum recorded only 13 inches (0.33 m) on February 11, 1968. The most snowfall in one year was 79.3 inches (2.01 m) from July 1946 to June 1947, including 37.0 inches (0.94 m) in November 1946.[14][15]

| Climate data for Tonopah Airport, Nevada, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1954–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

75 (24) |

79 (26) |

88 (31) |

96 (36) |

103 (39) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

90 (32) |

77 (25) |

70 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.3 (14.6) |

62.4 (16.9) |

71.2 (21.8) |

79.6 (26.4) |

88.1 (31.2) |

96.7 (35.9) |

100.1 (37.8) |

97.7 (36.5) |

91.8 (33.2) |

81.5 (27.5) |

69.1 (20.6) |

58.2 (14.6) |

100.8 (38.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 45.8 (7.7) |

49.3 (9.6) |

57.6 (14.2) |

64.3 (17.9) |

74.0 (23.3) |

85.3 (29.6) |

92.4 (33.6) |

90.4 (32.4) |

81.7 (27.6) |

68.4 (20.2) |

54.6 (12.6) |

44.6 (7.0) |

67.4 (19.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.9 (1.1) |

37.2 (2.9) |

43.8 (6.6) |

49.9 (9.9) |

59.0 (15.0) |

69.1 (20.6) |

75.7 (24.3) |

73.7 (23.2) |

65.7 (18.7) |

53.5 (11.9) |

41.0 (5.0) |

32.5 (0.3) |

52.9 (11.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.0 (−5.6) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

35.6 (2.0) |

44.1 (6.7) |

52.9 (11.6) |

59.1 (15.1) |

57.0 (13.9) |

49.6 (9.8) |

38.5 (3.6) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 5.7 (−14.6) |

12.1 (−11.1) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

32.0 (0.0) |

39.3 (4.1) |

49.9 (9.9) |

47.8 (8.8) |

38.3 (3.5) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

13.9 (−10.1) |

7.0 (−13.9) |

2.0 (−16.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) |

−9 (−23) |

4 (−16) |

9 (−13) |

19 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

40 (4) |

37 (3) |

24 (−4) |

10 (−12) |

3 (−16) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.45 (11) |

0.53 (13) |

0.52 (13) |

0.29 (7.4) |

0.51 (13) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.50 (13) |

0.39 (9.9) |

0.45 (11) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.26 (6.6) |

4.79 (120.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 36.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2,179 | — | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

_(19357624552).jpg.webp)

As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 2,627 people, 1,109 households, and 672 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 162.1 inhabitants per square mile (62.6/km2). There were 1,561 housing units at an average density of 96.3 per square mile (37.2/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 91.24% White, 1.41% Native American, 0.76% African American, 0.42% Asian, 0.30% Pacific Islander, 2.82% from other races, and 3.05% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.17% of the population.

There were 1,109 households, out of which 32.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.9% were married couples living together, 7.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.4% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 3.03.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 27.1% under the age of 18, 6.2% from 18 to 24, 29.3% from 25 to 44, 27.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 108.3 males. For every 100 women age 18 and over, there were 105.9 men.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $37,401, and the median income for a family was $47,917. Males had a median income of $40,018 versus $22,056 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $18,256. About 5.7% of families and 11.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.3% of those under age 18 and 19.1% of those age 65 or over.

Transportation

During the silver bonanza of the first decade of the 20th century, the need in the precious-metal fields for freight service led to construction of a network of local railroad lines across the Nevada desert to Tonopah. Examples include the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad, the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad, and the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad. Coal was hauled to the silver mines to power mine operations and also the stamp mills built in and around Tonopah to break apart the hard-rock ore for milling and refining.

As the railroad lines were reduced with the decline of mining and restructuring of railroads in the late 20th century, 18-wheelers became the dominant method of moving freight. Tonopah took on a new identity as an extreme freight destination. The chorus of the song "Willin'" by Lowell George of Little Feat on the albums Little Feat, Sailin' Shoes, and Waiting for Columbus refers to Tonopah, Nevada:

And I've been from Tucson to Tucumcari, Tehachapi to Tonopah.

I've driven every kind of rig that's ever been made;

driven the backroads so I wouldn't get weighed.

In the early 21st century, Tonopah is served by two U.S. Highways, Routes 6 and 95. There is no rail service. General aviation facilities are located at nearby Tonopah Airport. The nearest airport with scheduled passenger service is Mammoth Yosemite Airport, about 100 miles (160 km) away. The nearest major airports are Harry Reid International Airport in Las Vegas, and Reno–Tahoe International Airport in Reno, each more than 200 miles (320 km) away.

Daily bus service between Las Vegas, Tonopah, and Reno is provided by Salt Lake Express.[20]

Notable people

- Hugh Bradner, physicist and inventor of the neoprene wetsuit, which helped to revolutionize scuba diving[21]

- T. Brian Callister, physician and nationally known health care policy expert; practiced in Tonopah between 1991 and 1995

- Thomas Joseph Connolly, Catholic bishop of Baker

- Wyatt Earp, Western lawman and fortune seeker. Arrived in Tonopah in February, 1902 and opened the Northern Saloon.

- Barbara Graham, murderer. One of four women to be executed in California

- William Robert Johnson, Catholic bishop of Orange

- Andriza Mircovich, only prisoner to be executed by shooting in Nevada

- Tasker L. Oddie, 12th Governor of Nevada (1911-15) and United States Senator (1921-33); resident of Tonopah[22]

- Key D. Pittman, U.S. Senator (1913–40); resident of Tonopah

- Vail M. Pittman, 19th Governor of Nevada (1945–51); resident of Tonopah

- Mayme Schweble, gold prospector and politician, one of the first female residents of Tonopah

- Stalking Cat, man known for his extensive body modifications.

Places of interest

_in_Tonopah%252C_Nevada.jpg.webp)

- Mizpah Hotel, with construction begun in 1905, shortly after the town of Tonopah was founded, and finished in late 1908, after several delays.[23] The Mizpah Hotel was once the tallest building in the state.

- The Clown Motel, located next to the Tonopah Cemetery, is a popular place to stay because of all the reports of being haunted by 'ghost clowns' and miners who were killed in the 1911 Belmont Mine Fire. The motel was featured as a haunted location on Travel Channel's paranormal TV series' Ghost Adventures in 2017 and Most Terrifying Places in America in 2018.

In popular culture

- Tonopah was the subject of an episode of Rhett & Link: Commercial Kings.[24] Rhett and Link developed a slogan for the town "Visit Tonopah, We're Different".[25]

- A picture of Tonopah is featured as the last page of the Lucky Luke comic album Le Grand Duc (1973)

- Tonopah is mentioned in the lyrics to the song "Willin'" by the country rock band Little Feat

- The Garden mentions Tonopah in the song “What Else Could I Be But a Jester”

- The opening scene of the movie Melvin and Howard features the desert "outside of Tonopah" with Howard Hughes played by Jason Robards shown riding a dirt bike.

- Tonopah figures in the storylines of a number of episodes of the 1960s television series State Trooper. Though the show was largely filmed in Los Angeles, outdoor location shots featuring the Nye County Courthouse and downtown Tonopah were incorporated in the production.

References

Notes

- "Tonopah..."Queen of the Silver Camps", few places tell the story of Nevada's mining past better!". tonopahnevada.com. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Tonopah". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- Crum, B., Crum, E., & Dayley, J. P. (2001). Newe Hupia: Shoshoni Poetry Songs. University Press of Colorado. Pg. 214 doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt46nz00

- "Nye County Code - Section 22.02.010: Formation of Town". Sterling Codifiers. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Moe, Al W. (2008). The Roots of Reno. p. 20. ISBN 978-1439211991.

- "Tonopah | Tonopah NV | Where is Tonopah Nevada". Travel Nevada.

- "Concentrating Solar Power Projects - Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project". NREL. 10 November 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016.

- "USGS Earthquake Summary". earthquake.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Gross, Sam (May 15, 2020). "Earthquake near Tonopah upgraded to 6.5; Esmeralda County says several portions of US 95 damaged". Reno Gazette-Journal. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Varney, P (1990). "Appendix C: pronunciation guide". Southern California's best ghost towns: a practical guide. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-8061-2608-6.

- Carlson, Helen S. (1974). Nevada Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. pp. 233, 234. ISBN 0-87417-094-X.

- "Tonopah, Nevada Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary; Period of Record : 05/01/1902 to 06/09/2016". wrcc.dri.edu. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- "Tonopah, Nevada Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary; 06/11/1954 to 06/09/2016". wrcc.dri.edu. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Tonopah, NV". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Elko". National Weather Service. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Tonopah, NV". Salt Lake Express. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- Taylor, Michael (2008-05-11). "Hugh Bradner, UC's inventor of wetsuit, dies". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

- "Nevada Governor Tasker Lowndes Oddie". National Governors Association. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- "Notes from Tonopah, Nevada". Engineering and Mining Journal. New York: Hill Publishing Company. 86 (18): 871. 1908. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Henry Brean. "Ad puts quirky Tonopah on map". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Rhett & Link: Commercial Kings - Rhett & Link: Commercial Kings: Tonopah Commercial – IFC". Archived from the original on 2013-03-29. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

Further reading

- McCracken, Robert D., A History of Tonopah, Nevada (1992), ISBN 1-878138-52-9

- Glasscock, C.B., Gold in Them Hills: The Story of the Wests Last Wild Mining Days (1932) (Bobbs-Merrill)

External links

- Official website for town

- Tonopah photos and information at WesternMiningHistory.com Retrieved 22 October 2009

- Tonopah Historic Mining Park at Atlas Obscura

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NV-4, "Mizpah Mine, Tonopah, Nye County, NV", 26 photos, 7 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- Official website of the Central Nevada Museum — located in Tonopah.