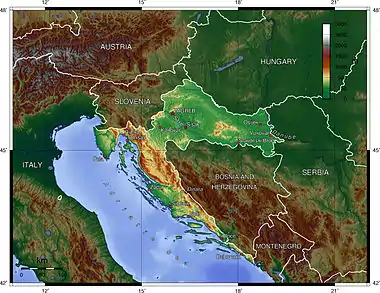

Topography of Croatia

Topography of Croatia is defined through three major geomorphological parts of the country. Those are the Pannonian Basin, the Dinaric Alps, and the Adriatic Basin. The largest part of Croatia consists of lowlands, with elevations of less than 200 metres (660 feet) above sea level recorded in 53.42% of the country. Bulk of the lowlands are found in the northern regions of the country, especially in Slavonia, itself a part of the Pannonian Basin plain. The plains are interspersed by the horst and graben structures, believed to break the Pannonian Sea surface as islands. The greatest concentration of ground at relatively high elevations is found in Lika and Gorski Kotar areas in the Dinaric Alps, but such areas are found in all regions of Croatia to some extent. The Dinaric Alps contain the highest mountain in Croatia—1,831-metre (6,007 ft) Dinara, as well as all other mountains in Croatia higher than 1,500 metres (4,900 feet). Croatia's Adriatic Sea mainland coast is 1,777.3 kilometres (1,104.4 miles) long, while its 1,246 islands and islets encompass further 4,058 kilometres (2,522 miles) of coastline—the most indented coastline in the Mediterranean. Karst topography makes up about half of Croatia and is especially prominent in the Dinaric Alps, as well as throughout the coastal areas and the islands.

Geomorphological units

The largest part of Croatia consists of lowlands, with elevations of less than 200 metres (660 feet) above sea level recorded in 53.42% of the country. Bulk of the lowlands are found in the northern regions of the country, especially in Slavonia, representing a part of the Pannonian Basin. Territory with elevations of 200 to 500 metres (660 to 1,640 feet) above sea level encompasses 25.61% of Croatia's territory, and the areas between 500 and 1,000 metres (1,600 and 3,300 feet) above sea level cover the 17.11% of the country. Further 3.71% of the land is situated at 1,000 to 1,500 metres (3,300 to 4,900 feet) above sea level, and only 0.15% of Croatia's territory lies at elevations greater than 1,500 metres (4,900 feet) above sea level.[1] The greatest concentration of ground at relatively high elevations is found in Lika and Gorski Kotar areas in the Dinaric Alps, but such areas are found in all regions of Croatia to some extent.[2] The Pannonian Basin and the Dinaric Alps, along with the Adriatic Basin represent major geomorphological parts of Croatia.[3]

Adriatic Basin

Croatia's Adriatic Sea mainland coast is 1,777.3 kilometres (1,104.4 miles) long, while its 1,246 islands and islets encompass further 4,058 kilometres (2,522 miles) of coastline. The distance between the extreme points of Croatia's coastline is 526 kilometres (327 miles).[4] The number of islands includes all islands, islets, and rocks of all sizes, including ones emerging at ebb tide only.[5] The islands include the largest ones in the Adriatic—Cres and Krk, each covering 405.78 square kilometres (156.67 square miles), and the tallest—Brač, whose peak reaches 780 metres (2,560 feet) above sea level. The islands include 48 permanently inhabited ones, the most populous among them being Krk and Korčula.[1]

The shore is the most indented coastline in the Mediterranean.[6] The majority of the coast is characterised by a karst topography, developed from the Adriatic Carbonate Platform. Karstification there largely began after the final uplift of the Dinarides in the Oligocene and the Miocene, when carbonate deposits were exposed to atmospheric effects, extending to the level of 120 metres (390 feet) below present sea level, exposed during the Last Glacial Maximum. It is estimated that some karst formations are related to earlier immersions, most notably the Messinian salinity crisis.[7] The largest part of the eastern coast consists of carbonate rocks, while flysch is significantly represented in the Gulf of Trieste coast, on the Kvarner Gulf coast opposite Krk, and in Dalmatia north of Split.[8] There are comparably small alluvial areas of the Adriatic coast in Croatia—most notably the Neretva Delta.[9] The western Istria is gradually subsiding, having sunk about 1.5 metres (4 feet 11 inches) in the past two thousand years.[10] In the Middle Adriatic Basin, there is evidence of Permian volcanism observed in area of Komiža on the island of Vis and as volcanic islands of Jabuka and Brusnik.[11]

Dinaric Alps

Formation of the Dinaric Alps is linked to a Late Jurassic to recent fold and thrust belt, itself a part of Alpine orogeny, extending southeast from the southern Alps.[12] The Dinaric Alps in Croatia encompass the entire Gorski Kotar and Lika regions, as well as considerable parts of Dalmatia, with their northeastern edge running from 1,181-metre (3,875 ft) Žumberak to Banovina region, along the Sava River,[13] and their westernmost landforms being 1,272-metre (4,173 ft) Ćićarija and 1,396-metre (4,580 ft) Učka mountains in Istria. The Dinaric Alps contain the highest mountain in Croatia—1,831-metre (6,007 ft) Dinara, as well as all other mountains in Croatia higher than 1,500 metres (4,900 feet)—Biokovo, Velebit, Plješivica, Velika Kapela, Risnjak, Svilaja and Snježnik.[1]

Karst topography makes up about half of Croatia and is especially prominent in the Dinaric Alps.[14] There are numerous caves in Croatia, 49 of which deeper than 250 metres (820.21 feet), 14 deeper than 500 metres (1,640.42 feet) and three deeper than 1,000 metres (3,280.84 feet).[15] The longest cave in Croatia, Kita Gaćešina, is at the same time the longest cave in the Dinaric Alps at 37,389 metres (122,667 feet).[16]

| Highest mountain peaks of Croatia[1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mountain | Peak | Elevation | Coordinates |

| Dinara | Dinara | 1,831 m (6,007 ft) | 44°3′N 16°23′E |

| Biokovo | Sveti Jure | 1,762 m (5,781 ft) | 43°20′N 17°03′E |

| Velebit | Vaganski vrh | 1,757 m (5,764 ft) | 44°32′N 15°14′E |

| Plješivica | Ozeblin | 1,657 m (5,436 ft) | 44°47′N 15°45′E |

| Velika Kapela | Bjelolasica – Kula | 1,533 m (5,030 ft) | 45°16′N 14°58′E |

| Risnjak | Risnjak | 1,528 m (5,013 ft) | 45°25′N 14°45′E |

| Svilaja | Svilaja | 1,508 m (4,948 ft) | 43°49′N 16°27′E |

| Snježnik | Snježnik | 1,506 m (4,941 ft) | 45°26′N 14°35′E |

Pannonian Basin

The Pannonian Basin took shape through Miocenian thinning and subsidence of crust structures formed during Late Paleozoic Variscan orogeny. The Paleozoic and Mesozoic structures are visible in Papuk and other Slavonian mountains. The processes also led to formation of a stratovolcanic chain in the basin 17 – 12 Mya and intensified subsidence observed until 5 Mya as well as flood basalts about 7.5 Mya. Contemporary uplift of the Carpathian Mountains severed water flow to the Black Sea and Pannonian Sea formed in the basin. Sediment were transported to the basin from uplifting Carpathian and Dinaric mountains, with particularly deep fluvial sediments being deposited in the Pleistocene during uplift of the Transdanubian Mountains.[17] Ultimately, up to 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) of the sediment was deposited in the basin, and the sea eventually drained through the Iron Gate gorge.[18]

The results of those processes are large plains in the eastern Slavonia, Baranya and Syrmia, as well as in river valleys, especially along Sava, Drava and Kupa. The plains are interspersed by the horst and graben structures, believed to break the Pannonian Sea surface as islands. The tallest among such landforms are 1,059-metre (3,474 ft) Ivanšćica and 1,035-metre (3,396 ft) Medvednica north of Zagreb and in Hrvatsko Zagorje as well as 984-metre (3,228 ft) Psunj and 953-metre (3,127 ft) Papuk which are the tallest among the Slavonian mountains surrounding Požega.[1] Psunj, Papuk and adjacent Krndija consist mostly of Paleozoic rocks which are 350 – 300 million years old. Požeška gora, adjacent to Psunj, consists of much more recent Neogene rocks, but there are also Upper Cretaceous sediments and igneous rocks forming the main, 30-kilometre (19 mi) ridge of the hill and representing the largest igneous landform in Croatia. A smaller igneous landform is also present on Papuk, near Voćin.[19] The two, as well as Moslavačka gora are possible remnants of a volcanic arc related to uplifting of the Dinaric Alps.[12]

See also

References

- "Geographical and Meteorological Data" (PDF). 2011 Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 43: 41. December 2011. ISSN 1333-3305. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "Land use - State and impacts (Croatia)". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Drugo, trece i cetvrto nacionalno izvješće Republike Hrvatske prema Okvirnoj konvenciji Ujedinjenih naroda o promjeni klime (UNFCCC)" [The second, third and fourth national report of the Republic of Croatia pursuant to the United Nations Framework Climate Change Convention (UNFCCC)] (PDF) (in Croatian). Ministry of Construction and Spatial Planning (Croatia). November 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Gerald Henry Blake; Duško Topalović; Clive H. Schofield (1996). The maritime boundaries of the Adriatic Sea. IBRU. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-897643-22-8. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Josip Faričić; Vera Graovac; Anica Čuka (June 2010). "Croatian small islands – residential and/or leisure area". Geoadria. University of Zadar. 15 (1): 145–185. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Biliana Cicin-Sain; Igor Pavlin; Stefano Belfiore (2002). Sustainable coastal management: a transatlantic and Euro-Mediterranean perspective. Springer. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-1-4020-0888-7.

- Maša Surić (June 2005). "Submerged Karst – Dead or Alive? Examples from the Eastern Adriatic Coast (Croatia)". Geoadria. University of Zadar. 10 (1): 5–19. ISSN 1331-2294. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Siegfried Siegesmund (2008). Tectonic aspects of the Alpine-Dinaride-Carpathian system. Geological Society. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-1-86239-252-6.

- Jasmina Mužinić (2007). "The Neretva Delta: Green Pearl of Coastal Croatia". Croatian Medical Journal. 48 (2): 127–129. PMC 2121601.

- F. Antonioli; et al. (2007). "Sea-level change during the Holocene in Sardinia and in the northeastern Adriatic (central Mediterranean Sea) from archaeological and geomorphological data" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. Elsevier. 26 (19–21): 2463–2486. Bibcode:2007QSRv...26.2463A. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.06.022. ISSN 0277-3791.

- Branimir Vukosav (30 April 2011). "Ostaci prastarog vulkana u Jadranu" [Remains of an ancient volcano in the Adriatic Sea]. Zadarski list (in Croatian). Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- Vlasta Tari-Kovačić (2002). "Evolution of the northern and western Dinarides: a tectonostratigraphic approach" (PDF). EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series. Copernicus Publications. 1 (1): 223–236. Bibcode:2002SMSPS...1..223T. doi:10.5194/smsps-1-223-2002. ISSN 1868-4556.

- William B. White; David C. Culver, eds. (2012). Encyclopedia of Caves. Academic Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-12-383833-9. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Mate Matas (18 December 2006). "Raširenost krša u Hrvatskoj" [Presence of Karst in Croatia]. geografija.hr (in Croatian). Croatian Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "The best national parks of Europe". BBC. 28 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- "Postojna više nije najdulja jama u Dinaridima: Rekord drži hrvatska Kita Gaćešina" [Postojna is no longer the longest cave in the Dinarides: The record is held by Croatia's Kita Gaćešina] (in Croatian). index.hr. 5 November 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Milos Stankoviansky; Adam Kotarba (2012). Recent Landform Evolution: The Carpatho-Balkan-Dinaric Region. Springer. pp. 14–18. ISBN 978-94-007-2447-1. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Dirk Hilbers (2008). The Nature Guide to the Hortobagy and Tisza River Floodplain, Hungary. Crossbill Guides Foundation. p. 16. ISBN 978-90-5011-276-5.

- Jakob Pamić; Goran Radonić; Goran Pavić. "Geološki vodič kroz park prirode Papuk" [Geological guide to the Papuk Nature Park] (PDF) (in Croatian). Papuk Geopark. Retrieved 2 March 2012.