Waterspout

A waterspout is an intense columnar vortex (usually appearing as a funnel-shaped cloud) that occurs over a body of water.[1] Some are connected to a cumulus congestus cloud, some to a cumuliform cloud and some to a cumulonimbus cloud.[2] In the common form, a waterspout is a non-supercell tornado over water having a five-part life cycle: formation of a dark spot on the water surface; spiral pattern on the water surface; formation of a spray ring; development of a visible condensation funnel; and ultimately, decay.[2][3][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

|

Most waterspouts do not suck up water; they are small, weak rotating columns of air over water.[2][5] Although typically weaker than their land counterparts, stronger versions—spawned by mesocyclones—do occasionally occur.[6][7]

While waterspouts form mostly in tropical and subtropical areas,[2] they are also reported in Europe, Western Asia (the Middle East),[8] Australia, New Zealand, the Great Lakes, Antarctica,[9][10] and on rare occasions, the Great Salt Lake.[11] Some are also found on the East Coast of the United States, and the coast of California.[1] Although rare, waterspouts have been observed in connection with lake-effect snow precipitation bands.

Characteristics

Climatology

Though the majority of waterspouts occur in the tropics, they can seasonally appear in temperate areas throughout the world, and are common across the western coast of Europe as well as the British Isles and several areas of the Mediterranean and Baltic Sea. They are not restricted to saltwater; many have been reported on lakes and rivers including the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River.[12] They are fairly common on the Great Lakes during late summer and early fall, with a record 66+ waterspouts reported over just a seven-day period in 2003.[13]

Waterspouts are more frequent within 100 km (60 mi) from the coast than farther out at sea. They are common along the southeast U.S. coast, especially off southern Florida and the Keys, and can happen over seas, bays, and lakes worldwide. Approximately 160 waterspouts are currently reported per year across Europe, with the Netherlands reporting the most at 60, followed by Spain and Italy at 25, and the United Kingdom at 15. They are most common in late summer. In the Northern Hemisphere, September has been pinpointed as the prime month of formation.[13] Waterspouts are also frequently observed off the east coast of Australia, with several being described by Joseph Banks during the voyage of the Endeavour in 1770.[14][15][16]

A family of four waterspouts seen on Lake Huron, 9 September 1999

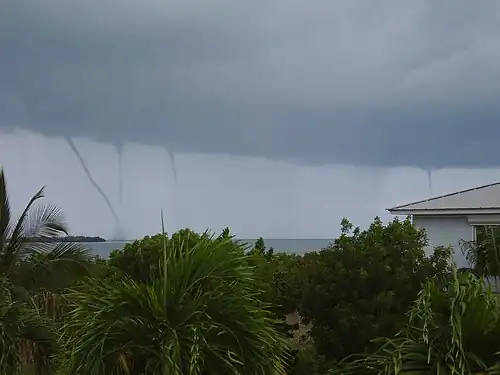

A family of four waterspouts seen on Lake Huron, 9 September 1999 Four waterspouts seen in the Florida Keys, 5 June 2009

Four waterspouts seen in the Florida Keys, 5 June 2009 Waterspout in the Tasman Sea, 29 January 2009

Waterspout in the Tasman Sea, 29 January 2009

Formation

Waterspouts exist on a microscale, where their environment is less than two kilometers in width. The cloud from which they develop can be as innocuous as a moderate cumulus, or as great as a supercell. While some waterspouts are strong and tornadic in nature, most are much weaker and caused by different atmospheric dynamics. They normally develop in moisture-laden environments as their parent clouds are in the process of development, and it is theorized they spin as they move up the surface boundary from the horizontal shear near the surface, and then stretch upwards to the cloud once the low-level shear vortex aligns with a developing cumulus cloud or thunderstorm. Some weak tornadoes, known as landspouts, have been shown to develop in a similar manner.[17]

More than one waterspout can occur simultaneously in the same vicinity. In 2012, as many as nine simultaneous waterspouts were reported on Lake Michigan in the United States.[9] In May 2021, at least five simultaneous waterspouts were filmed near Taree, off the northern coast of New South Wales, Australia.[14]

Types

Non-tornadic

Waterspouts that are not associated with a rotating updraft of a supercell thunderstorm are known as "non-tornadic" or "fair-weather" waterspouts. By far the most common type of waterspout, these occur in coastal waters and are associated with dark, flat-bottomed, developing convective cumulus towers. Fair-weather waterspouts develop and dissipate rapidly, having life cycles shorter than 20 minutes.[17] They usually rate no higher than EF0 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, generally exhibiting winds of less than 30 m/s (67 mph; 108 km/h).[18]

They are most frequently seen in tropical and sub-tropical climates, with upwards of 400 per year observed in the Florida Keys.[19] They typically move slowly, if at all, since the cloud to which they are attached is horizontally static, being formed by vertical convective action rather than the subduction/adduction interaction between colliding fronts.[19][20] Fair-weather waterspouts are very similar in both appearance and mechanics to landspouts, and largely behave as such if they move ashore.[19]

There are five stages to a fair-weather waterspout life cycle. Initially, a prominent circular, light-colored disk appears on the surface of the water, surrounded by a larger dark area of indeterminate shape. After the formation of these colored disks on the water, a pattern of light- and dark-colored spiral bands develops from the dark spot on the water surface. Then, a dense annulus of sea spray, called a "cascade", appears around the dark spot with what appears to be an eye. Eventually, the waterspout becomes a visible funnel from the water surface to the overhead cloud. The spray vortex can rise to a height of several hundred feet or more, and often creates a visible wake and an associated wave train as it moves. Finally, the funnel and spray vortex begin to dissipate as the inflow of warm air into the vortex weakens, ending the waterspout's life cycle.[20]

Tornadic

"Tornadic waterspouts", also accurately referred to as "tornadoes over water", are formed from mesocyclones in a manner essentially identical to land-based tornadoes in connection with severe thunderstorms, but simply occurring over water.[21] A tornado which travels from land to a body of water would also be considered a tornadic waterspout.[22] Since the vast majority of mesocyclonic thunderstorms in the United States occur in land-locked areas, true tornadic waterspouts are correspondingly rarer than their fair-weather counterparts in that country. However, in some areas, such as the Adriatic, Aegean and Ionian seas,[23] tornadic waterspouts can make up half of the total number.[24]

Snowspout

A winter waterspout, also known as an icespout, an ice devil, or a snowspout, is a rare instance of a waterspout forming under the base of a snow squall.[25] The term "winter waterspout" is used to differentiate between the common warm season waterspout and this rare winter season event. There are a couple of critical criteria for the formation of a winter waterspout. Very cold temperatures need to be present over a body of water, which is itself warm enough to produce fog resembling steam above the water's surface. Like the more efficient lake-effect snow events, winds focusing down the axis of long lakes enhance wind convergence and increase the likelihood of a winter waterspout developing.[26]

The terms "snow devil" and "snownado" describe a different phenomenon: a snow vortex close to the surface with no parent cloud, similar to a dust devil.[27]

Impacts

Human

Waterspouts have long been recognized as serious marine hazards. Stronger waterspouts pose a threat to watercraft, aircraft and people.[28] It is recommended to keep a considerable distance from these phenomena, and to always be on alert through weather reports. The United States National Weather Service will often issue special marine warnings when waterspouts are likely or have been sighted over coastal waters, or tornado warnings when waterspouts are expected to move onshore.[29]

Incidents of waterspouts causing severe damage and casualties are rare; however, there have been several notable examples. The Malta tornado of 1551 was the earliest recorded occurrence of a deadly waterspout. It struck the Grand Harbour of Valletta, sinking four galleys and numerous boats, and claiming hundreds of lives.[30] The 1851 Sicily tornadoes were twin waterspouts that made landfall in western Sicily, ravaging the coast and countryside before ultimately dissipating back again over the sea.

Natural

Depending on how fast the winds from a waterspout are whipping, anything that is within about 90 cm (1 yard) of the surface of the water, including fish of different sizes, frogs, and even turtles, can be lifted into the air.[31] A waterspout can sometimes suck small animals such as fish out of the water and all the way up into the cloud. Even if the waterspout stops spinning, the fish in the cloud can be carried over land, buffeted up and down and around with the cloud's winds until its currents no longer keep the flying fish in the atmosphere. Depending on how far they travel and how high they are taken into the atmosphere, the fish are sometimes dead by the time they rain down. People as far as 160 km (100 miles) inland have experienced raining fish.[31] Fish can also be sucked up from rivers, but raining fish is not a common weather phenomenon.[31]

Research and forecasting

The Szilagyi Waterspout Index (SWI), developed by Canadian meteorologist Wade Szilagyi, is used to predict conditions favorable for waterspout development. The SWI ranges from −10 to +10, where values greater than or equal to zero represent conditions favorable for waterspout development.[32][33]

The International Centre for Waterspout Research (ICWR) is a non-governmental organization of individuals from around the world who are interested in the field of waterspouts from a research, operational and safety perspective.[34] Originally a forum for researchers and meteorologists, the ICWR has expanded interest and contribution from storm chasers, the media, the marine and aviation communities and from private individuals.

Myths

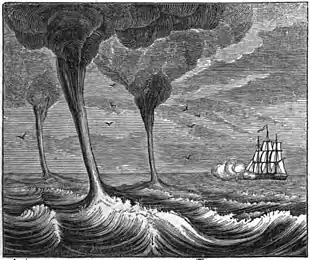

There was a commonly held belief among sailors in the 18th and 19th centuries that shooting a broadside cannon volley dispersed waterspouts.[35][36][37] Among others, Captain Vladimir Bronevskiy claims that it was a successful technique, having been an eyewitness to the dissipation of a phenomenon in the Adriatic while a midshipman aboard the frigate Venus during the 1806 campaign under Admiral Senyavin.[38]

A waterspout has been proposed as a reason for the abandonment of the Mary Celeste.[39]

See also

References

- Burt, Christopher (2004). Extreme weather : a guide & record book. Cartography by Stroud, Mark. (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393326581. OCLC 55671731.

- "A Comprehensive Glossary of Weather: Waterspout definition". geographic.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- What Is a Waterspout? (Weather Channel video)

- Jessica Hamilton Young (17 July 2016). "Waterspout comes ashore in Galveston". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016.

- Schwiesow, R.L.; Cupp, R.E.; Sinclair, P.C.; Abbey, R.F. (April 1981). "Waterspout Velocity Measurements by Airborne Doppler Lidar". Journal of Applied Meteorology. 20 (4): 341–348. Bibcode:1981JApMe..20..341S. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1981)020<0341:WVMBAD>2.0.CO;2.

- "Waterspout". answers.com. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Keith C. Heidorn. Islandnet.com (ed.). "Water Twisters". The Weather Doctor Almanach. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Lewis, Avi (3 November 2014). "Waterspout wows Tel Aviv waterfront". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Several waterspouts filmed on Lake Michigan in US". BBC News. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Taylor, Stanley (13 January 1913). "Antarctic Diary Part 4: The S.Y. Aurora's stay in Commonwealth Bay Adelie Land waiting for Dr Douglas Mawson and the Far East Party to return, working on the Marconi Wireless". antarcticdiary.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Joanne Simpson; G. Roff; B. R. Morton; K. Labas; G. Dietachmayer; M. McCumber; R. Penc (December 1991). "A Great Salt Lake Waterspout". Monthly Weather Review. AMS. 119 (12): 2741–2770. Bibcode:1991MWRv..119.2741S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-119-12-2740.1.

- Canadian Television News Staff (23 July 2008). "Rare waterspout forms in Montreal during storm". CTV News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Wade Szilagyi (December 2004). "The Great Waterspout Outbreak of 2003". Mariners Weather Log. Vol. 48, no. 3. NOAA. Archived from the original on 21 October 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- Elizabeth Daoud (4 May 2021). "Astonishing moment FIVE waterspouts are seen at the same time off NSW coast". 7news.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022.

- Banks, Joseph (1997). The Endeavour Journal of Sir Joseph Banks, 1768–1771. University of Sydney Library.

- Gibson, Jano (14 June 2007). "Waterspout off Sydney". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- Choy, Barry K.; Spratt, Scott M. "Using the WSR-88D to Predict East Central Florida Waterspouts". srh.noaa.gov. NOAA. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office (30 April 2008). "Threat Definitions for Waterspouts". crh.noaa.gov. Milwaukee/Sullivan, WI: National Weather Service Central Region Headquarters. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- National Weather Service (12 September 2002). "Basic Spotter Training Version 1.2". srh.noaa.gov. Key West, FL: NOAA. pp. 4–24. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- Bruce B. Smith (22 February 2007). "Waterspouts". weather.gov. National Weather Service Central Region Headquarters. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- National Weather Service Forecast Office (25 January 2007). "Graphical Hazardous Weather Outlook: Waterspout Threat". srh.noaa.gov. Melbourne, FL: Southern Region Headquarters. Archived from the original on 19 December 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Waylon G. Collins; Charles H. Paxton; Joseph H. Golden (February 2000). "The 12 July 1995 Pinellas County, Florida, Tornado/Waterspout". Weather and Forecasting. 15 (1): 122–134. Bibcode:2000WtFor..15..122C. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2000)015<0122:TJPCFT>2.0.CO;2.

- "Rare: Waterspout tornado came ashore in Palermo, Sicily, Italy". Disasters News channel. 6 August 2020 – via YouTube.

- Michalis V. Sioutasa & Alexander G. Keul (February 2007). "Waterspouts of the Adriatic, Ionian and Aegean Sea and their meteorological environment". Journal of Atmospheric Research. 83 (2–4): 542–557. Bibcode:2007AtmRe..83..542S. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2005.08.009.

- "Waterspouts". The Buffalo News. SUNY Buffalo. 14 April 2003. Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- National Weather Service Forecast Office (3 February 2009). "15 January 2009: Lake Champlain Sea Smoke, Steam Devils, and Waterspouts: Chapters IV and V" (PDF). weather.gov. Burlington, VT: Eastern Region Headquarters. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- "Snow Devil". International Cloud Atlas. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- Auslan Cramb (7 August 2003). "Water Spout Hit Helicopter". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- National Weather Service Forecast Office (25 January 2007). "Graphical Hazardous Weather Outlook: Waterspout Threat". srh.weather.gov. Melbourne, FL: Southern Region Headquarters. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Abela, Joe. "Claude de la Sengle (1494–1557)". islalocalcouncil.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- Susan Cosier (17 September 2006). "It's Raining Fish: Unusual objects sometimes fall from the sky, courtesy of waterspouts". Scienceline (Physical Science). NYU Journalism. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Szilagyi, W. (15 September 2009). "A Waterspout Forecasting Technique" (PDF). Pre-prints. 5th European Conference on Severe Storms. Landshut – GERMANY. pp. 129–130.

- Sioutas, M.; Szilagyi, W.; Keul, A. (2013). "Waterspout outbreaks over areas of Europe and North America: Environment and predictability". Atmospheric Research. 123: 167–179. Bibcode:2013AtmRe.123..167S. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2012.09.013.

- "The International Centre For Waterspout Research (ICWR), "understanding our atmosphere through global cooperation."". Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure. Vol. 6–7. 1750. p. 154.

- American Journal of Science and Arts. S. Converse. 1849. p. 266.

- Robert Johnson (1810). The Adventures of Captain Robert Johnson. Thomas Tegg. p. B2.

- Naval Memoirs of Vladimir Brovevskiy (in Russian). Тип. Императорской Росс. Акад. 1837. p. 322.

- Begg, Paul (2007). Mary Celeste: The Greatest Mystery of the Sea. Harlow: Pearson Education. pp. 140–146. ISBN 978-1-4058-3621-0.

External links

General

- A series of pictures from the boat Nicorette approaching the NSW south coast tornadic waterspout.

- Pictures of cold-core waterspouts over Lake Michigan on 30 September 2006. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007.

- Large waterspout off southern Tongatapu, February 2014

- http://aoss-research.engin.umich.edu/PlanetaryEnvironmentResearchLaboratory/

- Experimental Great Lakes Forecast

- "Sand and Water spouts". Scientific American. Historical perspective. 43 (26): 407. 25 December 1880. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican12251880-407.

- A Winter Waterspout Monthly Weather Review, February 1907.