Blizzard

A blizzard is a severe snowstorm characterized by strong sustained winds and low visibility, lasting for a prolonged period of time—typically at least three or four hours. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow is not falling but loose snow on the ground is lifted and blown by strong winds. Blizzards can have an immense size and usually stretch to hundreds or thousands of kilometres.

| Blizzard | |

|---|---|

Heavy snow during the January 2016 United States blizzard. | |

| Area of occurrence | Temperate and polar regions, high mountains. |

| Season | Usually winter. |

| Effect | Power outages, dangerous travel conditions. |

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

|

Definition and etymology

In the United States, the National Weather Service defines a blizzard as a severe snow storm characterized by strong winds causing blowing snow that results in low visibilities. The difference between a blizzard and a snowstorm is the strength of the wind, not the amount of snow. To be a blizzard, a snow storm must have sustained winds or frequent gusts that are greater than or equal to 56 km/h (35 mph) with blowing or drifting snow which reduces visibility to 400 m or 0.25 mi or less and must last for a prolonged period of time—typically three hours or more.[1][2]

Environment Canada defines a blizzard as a storm with wind speeds exceeding 40 km/h (25 mph) accompanied by visibility of 400 metres (0.25 mi) or less, resulting from snowfall, blowing snow, or a combination of the two. These conditions must persist for a period of at least four hours for the storm to be classified as a blizzard, except north of the arctic tree line, where that threshold is raised to six hours.[3]

The Australia Bureau of Meteorology describes a blizzard as, "Violent and very cold wind which is laden with snow, some part, at least, of which has been raised from snow covered ground." [4]

While severe cold and large amounts of drifting snow may accompany blizzards, they are not required. Blizzards can bring whiteout conditions, and can paralyze regions for days at a time, particularly where snowfall is unusual or rare.

A severe blizzard has winds over 72 km/h (45 mph), near zero visibility, and temperatures of −12 °C (10 °F) or lower.[5] In Antarctica, blizzards are associated with winds spilling over the edge of the ice plateau at an average velocity of 160 km/h (99 mph).[5]

Ground blizzard refers to a weather condition where loose snow or ice on the ground is lifted and blown by strong winds. The primary difference between a ground blizzard as opposed to a regular blizzard is that in a ground blizzard no precipitation is produced at the time, but rather all the precipitation is already present in the form of snow or ice at the surface.

The Oxford English Dictionary concludes the term blizzard is likely onomatopoeic, derived from the same sense as blow, blast, blister, and bluster; the first recorded use of it for weather dates to 1829, when it was defined as a "violent blow". It achieved its modern definition by 1859, when it was in use in the western United States. The term became common in the press during the harsh winter of 1880–81.[6]

United States storm systems

In the United States, storm systems powerful enough to cause blizzards usually form when the jet stream dips far to the south, allowing cold, dry polar air from the north to clash with warm, humid air moving up from the south.[2][7]

When cold, moist air from the Pacific Ocean moves eastward to the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains, and warmer, moist air moves north from the Gulf of Mexico, all that is needed is a movement of cold polar air moving south to form potential blizzard conditions that may extend from the Texas Panhandle to the Great Lakes and Midwest. A blizzard also may be formed when a cold front and warm front mix together and a blizzard forms at the border line.

Another storm system occurs when a cold core low over the Hudson Bay area in Canada is displaced southward over southeastern Canada, the Great Lakes, and New England. When the rapidly moving cold front collides with warmer air coming north from the Gulf of Mexico, strong surface winds, significant cold air advection, and extensive wintry precipitation occur.

Low pressure systems moving out of the Rocky Mountains onto the Great Plains, a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie, steppe and grassland, can cause thunderstorms and rain to the south and heavy snows and strong winds to the north. With few trees or other obstructions to reduce wind and blowing, this part of the country is particularly vulnerable to blizzards with very low temperatures and whiteout conditions. In a true whiteout, there is no visible horizon. People can become lost in their own front yards, when the door is only 3 m (10 ft) away, and they would have to feel their way back. Motorists have to stop their cars where they are, as the road is impossible to see.

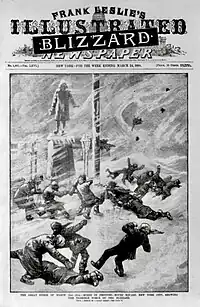

Nor'easter blizzards

A nor'easter is a macro-scale storm that occurs off the New England and Atlantic Canada coastlines. It gets its name from the direction the wind is coming from. The usage of the term in North America comes from the wind associated with many different types of storms, some of which can form in the North Atlantic Ocean and some of which form as far south as the Gulf of Mexico. The term is most often used in the coastal areas of New England and Atlantic Canada. This type of storm has characteristics similar to a hurricane. More specifically, it describes a low-pressure area whose center of rotation is just off the coast and whose leading winds in the left-forward quadrant rotate onto land from the northeast. High storm waves may sink ships at sea and cause coastal flooding and beach erosion. Notable nor'easters include The Great Blizzard of 1888, one of the worst blizzards in U.S. history. It dropped 100–130 cm (40–50 in) of snow and had sustained winds of more than 45 miles per hour (72 km/h) that produced snowdrifts in excess of 50 feet (15 m). Railroads were shut down and people were confined to their houses for up to a week. It killed 400 people, mostly in New York.[8]

Historic events

1972 Iran blizzard

The 1972 Iran blizzard, which caused 4,000 reported deaths, was the deadliest blizzard in recorded history. Dropping as much as 26 feet (7.9 m) of snow, it completely covered 200 villages. After a snowfall lasting nearly a week, an area the size of Wisconsin was entirely buried in snow.[9][10]

2008 Afghanistan blizzard

The 2008 Afghanistan blizzard, was a fierce blizzard that struck Afghanistan on the 10th of January 2008. Temperatures fell to a low of −30 °C (−22 °F), with up to 180 centimetres (71 in) of snow in the more mountainous regions, killing at least 926 people. It was the third deadliest blizzard in history. The weather also claimed more than 100,000 sheep and goats, and nearly 315,000 cattle died.[11]

The Snow Winter of 1880–1881

The winter of 1880–1881 is widely considered the most severe winter ever known in many parts of the United States.

The initial blizzard in October of 1880 brought snowfalls so deep that two-story homes experienced accumulations, as opposed to drifts, up to their second floor windows. No one was prepared for deep snow so early in the winter. Farmers from North Dakota to Virginia were caught flat with fields unharvested, what grain that had been harvested unmilled, and their suddenly all-important winter stocks of wood fuel only partially collected. By January train service was almost entirely suspended from the region. Railroads hired scores of men to dig out the tracks but as soon as they had finished shoveling a stretch of line a new storm arrived, burying it again.

There were no winter thaws and on February 2, 1881, a second massive blizzard struck that lasted for nine days. In towns the streets were filled with solid drifts to the tops of the buildings and tunneling was necessary to move about. Homes and barns were completely covered, compelling farmers to construct fragile tunnels in order to feed their stock.

When the snow finally melted in late spring of 1881 huge sections of the plains experienced flooding. Massive ice jams clogged the Missouri River and when they broke the downstream areas were inundated. Most of the town of Yankton, in what is now South Dakota, was washed away when the river overflowed its banks after the thaw.[12][13]

Novelization

Many children—and their parents—learned of "The Snow Winter" through the children's book The Long Winter by Laura Ingalls Wilder, in which the author tells of her family's efforts to survive. The snow arrived in October 1880 and blizzard followed blizzard throughout the winter and into March 1881, leaving many areas snowbound throughout the entire winter. Accurate details in Wilder's novel include the blizzards' frequency and the deep cold, the Chicago and North Western Railway stopping trains until the spring thaw because the snow made the tracks impassable, the near-starvation of the townspeople, and the courage of her future husband Almanzo and another man, Cap Garland, who ventured out on the open prairie in search of a cache of wheat that no one was even sure existed.

The Storm of the Century

The Storm of the Century, also known as the Great Blizzard of 1993, was a large cyclonic storm that formed over the Gulf of Mexico on March 12, 1993, and dissipated in the North Atlantic Ocean on March 15. It is unique for its intensity, massive size and wide-reaching effect. At its height, the storm stretched from Canada towards Central America, but its main impact was on the United States and Cuba. The cyclone moved through the Gulf of Mexico, and then through the Eastern United States before moving into Canada. Areas as far south as northern Alabama and Georgia received a dusting of snow and areas such as Birmingham, Alabama, received up to 12 in (30 cm) [14] with hurricane-force wind gusts and record low barometric pressures. Between Louisiana and Cuba, hurricane-force winds produced high storm surges across northwestern Florida, which along with scattered tornadoes killed dozens of people. In the United States, the storm was responsible for the loss of electric power to over 10 million customers. It is purported to have been directly experienced by nearly 40 percent of the country's population at that time. A total of 310 people, including 10 from Cuba, perished during this storm. The storm cost $6 to $10 billion in damages.

List of blizzards

North America

1700 to 1799

- The Great Snow 1717 series of four snowstorms between February 27 and March 7, 1717. There were reports of about five feet of snow already on the ground when the first of the storms hit. By the end, there were about ten feet of snow and some drifts reaching 25 feet (7.6 m), burying houses entirely. In the colonial era, this storm made travel impossible until the snow simply melted.[15]

- Blizzard of 1765. March 24, 1765. Affected area from Philadelphia to Massachusetts. High winds and over 2 feet (61 cm) of snowfall recorded in some areas.[16]

- Blizzard of 1772. "The Washington and Jefferson Snowstorm of 1772". January 26–29, 1772. One of largest D.C. and Virginia area snowstorms ever recorded. Snow accumulations of 3 feet (91 cm) recorded.[17]

- The "Hessian Storm of 1778". December 26, 1778. Severe blizzard with high winds, heavy snows and bitter cold extending from Pennsylvania to New England. Snow drifts reported to be 15 feet (4.6 m) high in Rhode Island. Storm named for stranded Hessian troops in deep snows stationed in Rhode Island during the Revolutionary War.[16]

- The Great Snow of 1786. December 4–10, 1786. Blizzard conditions and a succession of three harsh snowstorms produced snow depths of 2 feet (61 cm) to 4 feet (120 cm) from Pennsylvania to New England. Reportedly of similar magnitude of 1717 snowstorms.[18]

- The Long Storm of 1798. November 19–21, 1798. Heavy snowstorm produced snow from Maryland to Maine.[18]

1800 to 1850

- Blizzard of 1805. January 26–28, 1805. Cyclone brought heavy snowstorm to New York City and New England. Snow fell continuously for two days where over 2 feet (61 cm) of snow accumulated.[19]

- New York City Blizzard of 1811. December 23–24, 1811. Severe blizzard conditions reported on Long Island, in New York City, and southern New England. Strong winds and tides caused damage to shipping in harbor.[19]

- Luminous Blizzard of 1817. January 17, 1817. In Massachusetts and Vermont, a severe snowstorm was accompanied by frequent lightning and heavy thunder. St. Elmo's fire reportedly lit up trees, fence posts, house roofs, and even people. John Farrar professor at Harvard, recorded the event in his memoir in 1821.[20]

- Great Snowstorm of 1821. January 5–7, 1821. Extensive snowstorm and blizzard spread from Virginia to New England.[19]

- Winter of Deep Snow in 1830. December 29, 1830. Blizzard storm dumped 36 inches (91 cm) in Kansas City and 30 inches (76 cm) in Illinois. Areas experienced repeated storms thru mid-February 1831.[21]

- "The Great Snowstorm of 1831" January 14–16, 1831. Produced snowfall over widest geographic area that was only rivaled, or exceeded by, the 1993 Blizzard. Blizzard raged from Georgia, to Ohio Valley, all the way to Maine.[19]

- "The Big Snow of 1836" January 8–10, 1836. Produced 30 inches (76 cm) to 40 inches (100 cm) of snowfall in interior New York, northern Pennsylvania, and western New England. Philadelphia got a reported 15 inches (38 cm) and New York City 2 feet (61 cm) of snow.[19]

1851 to 1900

- Plains Blizzard of 1856. December 3–5, 1856. Severe blizzard-like storm raged for three days in Kansas and Iowa. Early pioneers suffered.[22]

- "The Cold Storm of 1857" January 18–19, 1857. Produced severe blizzard conditions from North Carolina to Maine. Heavy snowfalls reported in east coast cities.[23]

- Midwest Blizzard of 1864. January 1, 1864. Gale-force winds, driving snow, and low temperatures all struck simultaneously around Chicago, Wisconsin and Minnesota.[24]

- Plains Blizzard of 1873. January 7, 1873. Severe blizzard struck the Great Plains. Many pioneers from the east were unprepared for the storm and perished in Minnesota and Iowa.[25]

- Great Plains Easter Blizzard of 1873. April 13, 1873

- Seattle Blizzard of 1880. January 6, 1880. Seattle area's greatest snowstorm to date. An estimated 4 feet (120 cm) fell around the town. Many barns collapsed and all transportation halted.[25]

- The Hard Winter of 1880-81. October 15, 1880. A blizzard in eastern South Dakota marked the beginning of this historically difficult season. Laura Ingalls Wilder's book The Long Winter details the effects of this season on early settlers.

- In the three year winter period from December 1885 to March 1888, the Great Plains and Eastern United States suffered a series of the worst blizzards in this nation's history ending with the Schoolhouse Blizzard and the Great Blizzard of 1888. The massive explosion of the volcano Krakatoa in the South Pacific late in August 1883 is a suspected cause of these huge blizzards during these several years. The clouds of ash it emitted continued to circulate around the world for many years. Weather patterns continued to be chaotic for years, and temperatures did not return to normal until 1888. Record rainfall was experienced in Southern California during July 1883 to June 1884. The Krakatoa eruption injected an unusually large amount of sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas high into the stratosphere which reflects sunlight and helped cool the planet over the next few years until the suspended atmospheric sulfur fell to ground.

- Plains Blizzard of late 1885. In Kansas, heavy snows of late 1885 had piled drifts 10 feet (3.0 m) high.[26]

- Kansas Blizzard of 1886. First week of January 1886. Reported that 80 percent of the cattle were frozen to death in that state alone from the cold and snow.[26]

- January 1886 Blizzard. January 9, 1886. Same system as Kansas 1886 Blizzard that traveled eastward.

- Great Plains Blizzards of late 1886. On November 13, 1886, it reportedly began to snow and did not stop for a month in the Great Plains region.[27]

- Great Plains Blizzard of 1887. January 9–11, 1887. Reported 72-hour blizzard that covered parts of the Great Plains in more than 16 inches (41 cm) of snow. Winds whipped and temperatures dropped to around 50 °F (10 °C). So many cows that were not killed by the cold soon died from starvation. When spring arrived, millions of the animals were dead, with around 90 percent of the open range's cattle rotting where they fell. Those present reported carcasses as far as the eye could see. Dead cattle clogged up rivers and spoiled drinking water. Many ranchers went bankrupt and others simply called it quits and moved back east. The "Great Die-Up" from the blizzard effectively concluded the romantic period of the great Plains cattle drives.[28]

- Schoolhouse Blizzard of 1888 North American Great Plains. January 12–13, 1888. What made the storm so deadly was the timing (during work and school hours), the suddenness, and the brief spell of warmer weather that preceded it. In addition, the very strong wind fields behind the cold front and the powdery nature of the snow reduced visibilities on the open plains to zero. People ventured from the safety of their homes to do chores, go to town, attend school, or simply enjoy the relative warmth of the day. As a result, thousands of people—including many schoolchildren—got caught in the blizzard.

- Great Blizzard of March 1888 March 11–14, 1888. One of the most severe recorded blizzards in the history of the United States. On March 12, an unexpected northeaster hit New England and the mid-Atlantic, dropping up to 50 in (130 cm) of snow in the space of three days. New York City experienced its heaviest snowfall recorded to date at that time, all street railcars were stranded, and the storm led to the creation of the NYC subway system. Snowdrifts reached up to the second story of some buildings. Some 400 people died from this blizzard, including many sailors aboard vessels that were beset by gale-force winds and turbulent seas.

- Great Blizzard of 1899 February 11–14, 1899. An extremely unusual blizzard in that it reached into the far southern states of the US. It hit in February, and the area around Washington, D.C., experienced 51 hours straight of snowfall. The port of New Orleans was totally iced over; revelers participating in the New Orleans Mardi Gras had to wait for the parade routes to be shoveled free of snow. Concurrent with this blizzard was the extremely cold arctic air. Many city and state record low temperatures date back to this event, including all-time records for locations in the Midwest and South. State record lows: Nebraska reached −47 °F (−44 °C), Ohio experienced −39 °F (−39 °C), Louisiana bottomed out at −16 °F (−27 °C), and Florida dipped below zero to −2 °F (−19 °C).

1901 to 1939

- Great Lakes Storm of 1913 November 7–10, 1913. "The White Hurricane" of 1913 was the deadliest and most destructive natural disaster ever to hit the Great Lakes Basin in the Midwestern United States and the Canadian province of Ontario. It produced 90 mph (140 km/h) wind gusts, waves over 35 ft (11 m) high, and whiteout snowsqualls. It killed more than 250 people, destroyed 19 ships, and stranded 19 others.

- Blizzard of 1918. January 11, 1918. Vast blizzard-like storm moved through Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.[25]

- 1920 North Dakota blizzard March 15–18, 1920

- Knickerbocker Storm January 27–28, 1922

1940 to 1949

- Armistice Day Blizzard of 1940 November 10–12, 1940. Took place in the Midwest region of the United States on Armistice Day. This "Panhandle hook" winter storm cut a 1,000 mi-wide path (1,600 km) through the middle of the country from Kansas to Michigan. The morning of the storm was unseasonably warm but by mid afternoon conditions quickly deteriorated into a raging blizzard that would last into the next day. A total of 145 deaths were blamed on the storm, almost a third of them duck hunters who had taken time off to take advantage of the ideal hunting conditions. Weather forecasters had not predicted the severity of the oncoming storm, and as a result the hunters were not dressed for cold weather. When the storm began many hunters took shelter on small islands in the Mississippi River, and the 50 mph (80 km/h) winds and 5-foot (1.5 m) waves overcame their encampments. Some became stranded on the islands and then froze to death in the single-digit temperatures that moved in over night. Others tried to make it to shore and drowned.

- North American blizzard of 1947 December 25–26, 1947. Was a record-breaking snowfall that began on Christmas Day and brought the Northeast United States to a standstill. Central Park in New York City got 26 inches (66 cm) of snowfall in 24 hours with deeper snows in suburbs. It was not accompanied by high winds, but the snow fell steadily with drifts reaching 10 ft (3.0 m). Seventy-seven deaths were attributed to the blizzard.[21]

- The Blizzard of 1949 - The first blizzard started on Sunday, January 2, 1949; it lasted for three days. It was followed by two more months of blizzard after blizzard with high winds and bitter cold. Deep drifts isolated southeast Wyoming, northern Colorado, western South Dakota and western Nebraska, for weeks. Railroad tracks and roads were all drifted in with drifts of 20 feet (6.1 m) and more. Hundreds of people that had been traveling on trains were stranded. Motorists that had set out on January 2 found their way to private farm homes in rural areas and hotels and other buildings in towns; some dwellings were so crowded that there wasn't enough room for all to sleep at once. It would be weeks before they were plowed out. The Federal government quickly responded with aid, airlifting food and hay for livestock. The total rescue effort involved numerous volunteers and local agencies plus at least ten major state and federal agencies from the U.S. Army to the National Park Service. Private businesses, including railroad and oil companies, also lent manpower and heavy equipment to the work of plowing out. The official death toll was 76 people and one million livestock.[29][30] Youtube video Storm of the Century - the Blizzard of '49 Storm of the Century - the Blizzard of '49

1950 to 1959

- Great Appalachian Storm of November 1950 November 24–30, 1950

- March 1958 Nor'easter blizzard March 18–21, 1958.

- The Mount Shasta California Snowstorm of 1959 – The storm dumped 189 inches (480 cm) of snow on Mount Shasta. The bulk of the snow fell on unpopulated mountainous areas, barely disrupting the residents of the Mount Shasta area. The amount of snow recorded is the largest snowfall from a single storm in North America.

1960 to 1969

- March 1960 Nor'easter blizzard March 2–5, 1960

- December 1960 Nor'easter blizzard December 12–14, 1960. Wind gusts up to 50 miles per hour (80 km/h).[31]

- March 1962 Nor'easter Great March Storm of 1962 – Ash Wednesday. North Carolina and Virginia blizzards. Struck during Spring high tide season and remained mostly stationary for almost 5 days causing significant damage along eastern coast, Assateague island was under water, and dumped 42 inches (110 cm) of snow in Virginia.

- North American blizzard of 1966 January 27–31, 1966

- Chicago Blizzard of 1967 January 26–27, 1967

- February 1969 nor'easter February 8–10, 1969

- March 1969 Nor'easter blizzard March 9, 1969

- December 1969 Nor'easter blizzard December 25–28, 1969.

1970 to 1979

- The Great Storm of 1975 known as the "Super Bowl Blizzard" or "Minnesota's Storm of the Century". January 9–12, 1975. Wind chills of −50 °F (−46 °C) to −80 °F (−62 °C) recorded, deep snowfalls.[25]

- Groundhog Day gale of 1976 February 2, 1976

- Buffalo Blizzard of 1977 January 28 – February 1, 1977. There were several feet of packed snow already on the ground, and the blizzard brought with it enough snow to reach Buffalo's record for the most snow in one season – 199.4 inches (506 cm).[15]

- Great Blizzard of 1978 also called the "Cleveland Superbomb". January 25–27, 1978. Was one of the worst snowstorms the Midwest has ever seen. Wind gusts approached 100 mph (160 km/h), causing snowdrifts to reach heights of 25 ft (7.6 m) in some areas, making roadways impassable. Storm reached maximum intensity over southern Ontario Canada.

- Northeastern United States Blizzard of 1978 – February 6–7, 1978. Just one week following the Cleveland Superbomb blizzard, New England was hit with its most severe blizzard in 90 years since 1888.[32]

- Chicago Blizzard of 1979 January 13–14, 1979

1980 to 1989

- February 1987 Nor'easter blizzard February 22–24, 1987

1990 to 1999

- 1991 Halloween blizzard Upper Mid-West US, October 31 – November 3, 1991

- December 1992 Nor'easter blizzard December 10–12, 1992

- 1993 Storm of the Century March 12–15, 1993. While the southern and eastern U.S. and Cuba received the brunt of this massive blizzard, the Storm of the Century impacted a wider area than any in recorded history.

- February 1995 Nor'easter blizzard February 3–6, 1995

- Blizzard of 1996 January 6–10, 1996

- April Fool's Day Blizzard March 31 – April 1, 1997. US East Coast

- 1997 Western Plains winter storms October 24–26, 1997

- Mid West Blizzard of 1999 January 2–4, 1999

2000 to 2009

- January 25, 2000 Southeastern United States winter storm January 25, 2000. North Carolina and Virginia

- December 2000 Nor'easter blizzard December 27–31, 2000

- North American blizzard of 2003 February 14–19, 2003 (Presidents' Day Storm II)

- December 2003 Nor'easter blizzard December 6–7, 2003

- North American blizzard of 2005 January 20–23, 2005

- North American blizzard of 2006 February 11–13, 2006

- Early winter 2006 North American storm complex Late November 2006

- Colorado Holiday Blizzards (2006–07) December 20–29, 2006 Colorado

- February 2007 North America blizzard February 12–20, 2007

- January 2008 North American storm complex January, 2008 West Coast US

- North American blizzard of 2008 March 6–10, 2008

- 2009 Midwest Blizzard 6–8 December 2009, a bomb cyclogenesis event that also affected parts of Canada

- North American blizzard of 2009 December 16–20, 2009

- 2009 North American Christmas blizzard December 22–28, 2009

2010 to 2019

- February 5–6, 2010 North American blizzard February 5–6, 2010 Referred to at the time as Snowmageddon was a Category 3 ("major") nor'easter and severe weather event.

- February 9–10, 2010 North American blizzard February 9–10, 2010

- February 25–27, 2010 North American blizzard February 25–27, 2010

- October 2010 North American storm complex October 23–28, 2010

- December 2010 North American blizzard December 26–29, 2010

- January 31 – February 2, 2011 North American blizzard January 31 – February 2, 2011. Groundhog Day Blizzard of 2011

- 2011 Halloween nor'easter October 28 – Nov 1, 2011

- Hurricane Sandy October 29–31, 2012. West Virginia, western North Carolina, and southwest Pennsylvania received heavy snowfall and blizzard conditions from this hurricane

- November 2012 nor'easter November 7–10, 2012

- December 17–22, 2012 North American blizzard December 17–22, 2012

- Late December 2012 North American storm complex December 25–28, 2012

- February 2013 nor'easter February 7–20, 2013

- February 2013 Great Plains blizzard February 19 – March 6, 2013

- March 2013 nor'easter March 6, 2013

- October 2013 North American storm complex October 3–5, 2013

- Buffalo, NY blizzard of 2014. Buffalo got over 6 feet (1.8 m) of snow during November 18–20, 2014.

- January 2015 North American blizzard January 26–27, 2015

- Late December 2015 North American storm complex December 26–27, 2015 Was one of the most notorious blizzards in the state of New Mexico and West Texas ever reported. It had sustained winds of over 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) and continuous snow precipitation that lasted over 30 hours. Dozens of vehicles were stranded in small county roads in the areas of Hobbs, Roswell, and Carlsbad New Mexico. Strong sustained winds destroyed various mobile homes.

- January 2016 United States blizzard January 20–23, 2016

- February 2016 North American storm complex February 1–8, 2016

- February 2017 North American blizzard February 6–11, 2017

- March 2017 North American blizzard March 9–16, 2017

- Early January 2018 nor’easter January 3–6, 2018

- March 2019 North American blizzard March 8–16, 2019

- April 2019 North American blizzard April 10–14, 2019

2020 to present

- December 5–6, 2020 nor'easter December 5–6, 2020

- January 31 – February 3, 2021 nor'easter January 31 – February 3, 2021

- February 13–17, 2021 North American winter storm February 13–17, 2021

- March 2021 North American blizzard March 11–14, 2021

- January 2022 North American blizzard January 27–30, 2022

- Late December 2022 North American winter storm December 21–26, 2022

Canada

- The Eastern Canadian Blizzard of 1971 – Dumped a foot and a half (45.7 cm) of snow on Montreal and more than two feet (61 cm) elsewhere in the region. The blizzard caused the cancellation of a Montreal Canadiens hockey game for the first time since 1918.[33]

- Saskatchewan blizzard of 2007 – January 10, 2007 Canada

United Kingdom

- Great Frost of 1709

- Blizzard of January 1881

- Winter of 1894–95 in the United Kingdom

- Winter of 1946–1947 in the United Kingdom

- Winter of 1962–1963 in the United Kingdom

- January 1987 Southeast England snowfall

- Winter of 1990–91 in Western Europe

- February 2009 Great Britain and Ireland snowfall

- Winter of 2009–10 in Great Britain and Ireland

- Winter of 2010–11 in Great Britain and Ireland

- Early 2012 European cold wave

See also

References

- "Blizzard at the US National Weather Service glossary". Weather.gov. 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- "Blizzards". www.ussartf.org. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Canada, Environment and Climate Change (2010-07-26). "Criteria for public weather alerts". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- "Blizzard definition, Weather Words, Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology". Bom.gov.au. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- "Blizzard" Encyclopædia Britannica Online retrieved 17 March 2012

- Entry for Blizzard. Oxford English Dictionary.

- weather.com - Storm Encyclopedia Archived February 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- New York

- "40 Years Ago, Iran Was Hit by the Deadliest Blizzard in History". 7 February 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "بوران ۱۳۵۰: شدیدترین بوران تاریخ معاصر ایران و جهان". www.skyandweather.net. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Bitter winter a killer in Afghanistan". CBC News. 2008-02-10. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- "Prologue". archives.gov. 8 March 2012.

- Doane Robinson (1904), "Chapter LIII: Dakota Territory History – 1880–1881", History of South Dakota, vol. 1, pp. 306–309

- National Climatic Data Center (1993). "Event Details". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- "15 of the Worst Snowstorms in History". 9 February 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Northeast Snowstorms, Vol II. Kocin/Uccellini pg 299

- "Weather Events: The Washington and Jefferson Snowstorm of 1772". www.islandnet.com. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Northeast Snowstorms, Vol II. Kocin/Uccellini pg 301

- Northeast Snowstorms, Vol II. Kocin/Uccellini pg 303

- Extreme Weather record book, 2007 edition, pg 91, Christopher Burt

- The American Weather Book. David Ludlum pg 265

- The American Weather Book. David Ludlum pg 263

- Northeast Snowstorms, Vol II. Kocin/Uccellini pg 304

- The American Weather Book. David Ludlum pg 6

- The American Weather Book. David Ludlum pg 7

- "Blizzard of 1886 - Kansapedia - Kansas Historical Society". www.kshs.org. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Blizzard Years". www.acsu.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Clark, Laura (January 9, 2015). "The 1887 Blizzard That Changed the American Frontier Forever". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian.

- "Blizzard of '49 - Wyoming History". PBS. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Hein, Rebecca. "The Notorious Blizzard of 1949". The Wyoming State Historical Society. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- The American Weather Book. David Ludlum pg 264

- Extreme Weather record book, 2007 edition, pg 241, Christopher Burt

- "10 Biggest Snowstorms of All Time". 12 November 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

External links

- Digital Snow Museum Photos of historic blizzards and snowstorms.

- Farmers Almanac List of Worst Blizzards in the United States

- United States Search and Rescue Task Force: About Blizzards

- A Historical Review On The Origin and Definition of the Word Blizzard Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine Dr Richard Wild