March 2021 North American blizzard

The March 2021 North American blizzard was a record-breaking blizzard in the Rocky Mountains and a significant snowstorm in the Upper Midwest that occurred in mid-March of 2021. It brought Cheyenne, Wyoming their largest two-day snowfall on record, and Denver, Colorado their second-largest March snowfall on record. The storm originated from an extratropical cyclone in the northern Pacific Ocean in early March, arriving on the west coast of the United States by March 10. The storm moved into the Rocky Mountains on Saturday, March 13, dumping up to 2–3 feet (24–36 in) of snow in some areas. It was unofficially given the name Winter Storm Xylia.[4][5]

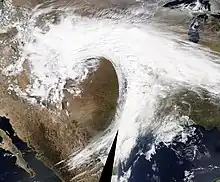

NASA satellite imagery of the winter storm over the Central United States on March 1 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 4, 2021 |

| Dissipated | March 17, 2021 |

| Category 3 "Major" winter storm | |

| Regional Snowfall Index: 7.84 (NOAA) | |

| Highest winds | 71 mph (114 km/h) in Douglas Pass, Colorado on March 15 |

| Lowest pressure | 980 mbar (hPa); 28.94 inHg |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion | 52.5 in (133 cm) at Windy Peak, Laramie Range, Wyoming[1] |

| Tornado outbreak | |

| Tornadoes | 21 |

| Maximum rating | EF2 tornado |

| Duration | 6 hours, 43 minutes |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Damage | >$75 million (2021 USD)[2] |

| Areas affected | Pacific Northwest, Western United States, Rocky Mountains, Southern United States, Midwestern United States, New England |

| Power outages | > 54,000[3] |

Part of the 2020–21 North American winter and tornado outbreaks of 2021 | |

Thousands lost power and several areas received some of their heaviest late-season snowfall on record. The system caused at least $75 million in damage, although no fatalities were reported.[2] The system was also responsible for a tornado outbreak in the Texas Panhandle on March 13, spawning 21 confirmed tornadoes. These tornadoes caused $1.285 million in damage.

Meteorological history

On March 4, a new extratropical low formed over the north central Pacific, within a larger extratropical storm. The system quickly split off from the parent low, and over the next couple of days, the storm moved southeastward while gradually intensifying, before reaching a peak intensity of 980 millibars (29 inHg) on March 6.[6] Afterward, the storm stalled off the coast of the Pacific Northwest for the next couple of days, while weakening, with the storm shedding its frontal system and weakening to 1,000 millibars (30 inHg) by 09:00 UTC on March 8.[7][8] On the next day, the storm slowly began to approach the West Coast, while developing multiple central lows in the process.[9] On March 10, the storm began moving ashore in California, while developing a new low-pressure center to the east, which became the dominant low by the next day, after the storm had moved inland.[10][11][12] The storm remained nearly stationary over the Western United States for another day, before resuming its eastward motion on March 12, as a disorganized storm system.[13] On the next day, the storm began approaching another system over the Central Plains while gradually strengthening, before merging with it early on March 14, with the winter storm organizing significantly and growing more powerful in the process.[14][15] On the night of March 13–14, a powerful low-level jet stream channeled large amounts of moisture from the Gulf of Mexico across the Southern Plains and into the storm, which enhanced precipitation from the storm and also contributed to the strengthening of the system.[1] On March 14, the winter storm developed a secondary low at the triple point of its occluded front, as the storm expanded in size. Later that day, the storm's central pressure reached a secondary peak of 998 millibars (29.5 inHg), while the storm was situated over the Central United States, with the center of low pressure being situated over southeastern Colorado.[16][17] For much of that day, the storm's central low remained nearly stationary, even as it was intensifying. The storm's cyclogenesis resulted in a tightening of the pressure gradient, which gave the storm a large and expansive wind field.[1]

Afterward, the storm gradually began to weaken as it slowly moved eastward, even as it continued expanding in size. The storm's eastern flank continued moving farther apart from the parent low during this time.[18] From March 14 to 15, another extratropical cyclone moving in from the Pacific Northwest helped speed up the storm's eastward motion.[1] Throughout March 15, the winter storm weakened significantly, with the storm's western flank breaking off into a new storm over Northern United States, while the storm's secondary low to the east dissipated. The storm reached the Southeastern United States and the Mid-Atlantic region on March 16, even as the storm grew increasingly disorganized, with the storm's central pressure rising to 1,012 millibars (29.9 inHg) by 18:00 UTC that day.[19][20] On March 17, the majority of the moisture from the winter storm was absorbed into a new storm developing off the coast of the Carolinas, as the former storm's low-pressure center stalled over West Virginia. Later that day, the winter storm dissipated over West Virginia.[21][22]

Preparations

Winter Storm Warnings and Blizzard Warnings were issued from March 12–13 in much of the Rocky Mountains, where the heaviest of the snowfall was expected to occur.

Rocky Mountains

In Colorado, where the winter storm had the potential to be the biggest March snowstorm since 2003, officials urged residents to prepare ahead of the storm. On March 10, as the system was moving ashore in the West Coast, the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) advised motorists to stay off the roads during the peak of the storm, due to potential whiteout and blizzard conditions being possible.[23] The city of Denver prepared to deploy snowplows ahead and during the storm to clear residential streets as needed. In addition, United Airlines offered waivers to flights expected to be impacted by the winter storm.[23]

Governor Mark Gordon of the state of Wyoming posted a warning on Twitter on March 13, advising residents to stay off the roads at all costs during the storm.[24] The Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) urged motorists to stay off the roads during the snow on March 12, and stated they were ready to deploy snow plows and materials to treat roadways.[25] Blizzard warnings were issued for parts of the state, including the city of Cheyenne, due to expected high wind gusts up to 50 mph (80 km/h) and heavy snowfall of up to 2 feet (24 in) expected. Blizzard warnings were later expanded southward along the Front Range to include Denver. In Sioux Falls, South Dakota, snow blew into traffic lights at intersections, making it impossible for drivers to tell if the lights were red, yellow or green.[26]

Southern Plains

On the morning of March 13, the Storm Prediction Center issued a moderate risk severe weather outlook for the Texas Panhandle, noting the potential for strong tornadoes.[27]

Impact

Rocky Mountains

The storm brought Cheyenne their largest two-day snowfall on record, with 30.8 inches (78 cm) falling from March 13–14. The storm closed schools and colleges, as well as city and state government buildings.[26] Schools and government offices also shut down in Casper.[26] Denver received their second-largest March snowfall on record, with 27.1 inches (69 cm) falling at the airport.[28][26] The storm was also Denver's fourth-largest snowstorm on record.[28][5] The storm shut down major highways, caused blizzard conditions across the region, forced more than 2,000 flights to be canceled, and left tens of thousands of people without power.[4][5] The Colorado Avalanche Information Center issued an avalanche warning for the Front Range area due to the heavy snow.[4] The Aurora Police Department in Colorado reported 25 to 30 vehicles were stranded on the E-470 toll road east of Denver.[26] Several interstate highways including Interstate 25, Interstate 70, Interstate 76 and Interstate 80 shut down.[3] Nearly 24,000 homes and businesses in Colorado remained without electricity on March 15.[26] The snowstorm also prevented the Los Angeles Kings to fly out of Denver, postponing a game against the St. Louis Blues.[29] Several school districts in South Dakota canceled classes due to the storm.[26] In Wyoming, schools in Laramie and Natrona counties announced they would be closed through the middle of the week as travel was nearly impossible.[30] The United States Postal Service also announced it is having difficulty delivering mail in some parts of Wyoming.[30] Outside of those two states, wind gusts reaching 69 mph (111 km/h) in Maeser, Utah.[3]

Midwest

Wind gusts reached 63 mph (101 km/h) in Ord, Nebraska and 59 mph (95 km/h) in Grand Island, Nebraska.[3]

In Minnesota, the State Patrol said 264 crashes were reported, and 22 of those involved injuries.[30] At least 13 tractor-trailers jackknifed and 251 vehicles spun out on the slick roadways.[30]

Southern Plains

Multiple tornadoes touched down across the Panhandle, mainly areas between Lubbock and Amarillo and points eastward. A large tornado prompted PDS tornado warnings for portions of Randall, Armstrong, and Carson counties.[31][32][33][34] After surveys, it was determined an EF2 tornado moved from southwest of Happy in Swisher County to east of Canyon in Randall County. As the tornado dissipated, a new tornado, rated EF1, formed and moved into Armstrong County, passing over Palo Duro Canyon. A third tornado was spawned just northeast of the second one, also crossing from Randall to Armstrong and lifting near Washburn, just before crossing into Carson County. Another EF2 tornado caused minor damage in Clarendon before strengthening and causing major damage near the Greenbelt Lake Reservoir.[35] The final tornado of the day was a EF2 tornado that touched down southwest of Ensign and caused minor damage including several sturdy wood electrical poles that were snapped.[36] Damage totaled $1.285 million.[37]

| EFU | EF0 | EF1 | EF2 | EF3 | EF4 | EF5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

Confirmed tornadoes

| EF# | Location | County / Parish | State | Start Coord. | Time (UTC) | Path length | Max width | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFU | WSW of Nazareth | Castro | TX | 34.5267°N 102.1505°W | 20:55–20:57 | 0.92 mi (1.48 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | A brief tornado was observed by a trained spotter. No damage occurred.[38] |

| EF2 | SW of Happy to ESE of Canyon | Swisher, Randall | TX | 34.7054°N 101.9869°W | 21:15–22:00 | 21.25 mi (34.20 km) | 1,000 yd (910 m) | Many electrical transmission lines were damaged, a cell phone tower was blown over, and power poles were snapped along the path of this large wedge tornado. Homes sustained significant roof damage, including one that lost a large section of its roof and had considerable damage to its exterior. Damage also occurred to outbuildings, trees, and fencing. The tornado spent much of its life cycle over mostly open land.[39][40][35][41][42] |

| EF1 | NW of Happy | Randall | TX | 34.8012°N 101.9115°W | 21:31–21:36 | 2.5 mi (4.0 km) | 500 yd (460 m) | This brief tornado was caught video by storm chasers and residents in the area. It was on the ground simultaneously with the EF2 tornado just to its south. A barn and power lines were damaged before the tornado was absorbed into the larger EF2 tornado.[43] |

| EF1 | N of Happy | Randall | TX | 34.8163°N 101.8576°W | 21:37–21:42 | 3.54 mi (5.70 km) | 100 yd (91 m) | This was a satellite tornado on the southern side of the main EF2 tornado. Radar and reports and video from storm chasers suggest this was also an anticyclonic tornado. A brief tornado debris signature was visible on doppler radar in association with this tornado as it snapped power poles along Interstate 27. No other damage occurred as this tornado tracked northeast and dissipated.[44] |

| EF1 | E of Canyon | Randall, Armstrong | TX | 34.9765°N 101.7275°W | 21:48–22:14 | 8.16 mi (13.13 km) | 800 yd (730 m) | This tornado was on the ground simultaneously with the Happy/Canyon EF2 tornado for several minutes as that tornado dissipated. Campgrounds were damaged at Palo Duro Canyon State Park. One cabin at the park lost its entire roof and travel trailers were flipped, including one which was destroyed. None of these trailers were anchored. Other damage at the state park including minor damage to weaker structures, and trees were damaged as well. The tornado became wider as it crossed Palo Duro Canyon. After crossing the canyon, the tornado traveled through a very rural area and lifted as another tornado formed in the vicinity.[39][35][45][46] |

| EF0 | N of Hart | Castro | TX | 34.4236°N 102.1134°W | 21:54–21:56 | 1.42 mi (2.29 km) | 30 yd (27 m) | A brief tornado flipped an irrigation pivot and caused minor roof damage to a metal building. A Texas Tech West Texas mesonet station located north of Hart measured an 87 mph (140 km/h) wind gust as the tornado passed nearby.[47] |

| EFU | SE of Nazareth | Castro | TX | 34.5248°N 102.0696°W | 21:55–21:57 | 0.3 mi (0.48 km) | 30 yd (27 m) | A brief tornado over open land was recorded on video and caused no damage.[48] |

| EF0 | E of Happy | Swisher, Randall | TX | 34.7335°N 101.7323°W | 22:05–22:11 | 3.23 mi (5.20 km) | 50 yd (46 m) | This tornado was caught on camera by storm chasers. Two power poles were broken in Swisher County.[49][50] |

| EF0 | NNE of Palo Duro Canyon to ESE of Washburn | Randall, Armstrong | TX | 35.0114°N 101.6449°W | 22:06–22:34 | 12.96 mi (20.86 km) | 1,000 yd (910 m) | This tornado was on the ground simultaneously with the Palo Duro Canyon EF1 tornado for several minutes as that tornado dissipated. Power poles and several outbuildings were damaged. A semi-truck was pushed over before the tornado lifted after crossing U.S. Highway 287. The tornado occurred over mostly open land and was likely stronger than its rating indicates, but it impacted few structures.[51][52] |

| EFU | ESE of Hale Center | Hale | TX | 34.0825°N 101.6966°W | 22:21 | 0.04 mi (0.064 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | A brief tornado was observed by storm spotters and caused no damage.[40][53] |

| EFU | NNE of Aiken | Hale | TX | 34.2333°N 101.4877°W | 22:46 | 0.05 mi (0.080 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | A very brief tornado was photographed by a trained spotter. No damage occurred.[54] |

| EFU | SW of Groom | Armstrong | TX | 35.1251°N 101.2360°W | 23:02–23:11 | 3.11 mi (5.01 km) | 800 yd (730 m) | The damage path of this tornado was inaccessible by road, and it was confirmed by radar and storm chasers.[55] |

| EFU | SW of Silverton | Briscoe | TX | 34.4504°N 101.32°W | 23:08 | 0.06 mi (0.097 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | A brief tornado in an open field was observed and photographed by storm spotters and caused no damage.[56] |

| EF2 | SSW of Clarendon to NE of Howardwick | Donley | TX | 34.8861°N 100.9292°W | 23:48–00:12 | 13.22 mi (21.28 km) | 1,200 yd (1,100 m) | A tornado moved into the southwest edge of Clarendon, causing minor damage to homes and to Clarendon College, with sheet metal torn off the building. The tornado widened as it moved towards and then across Greenbelt Reservoir and into Howardwick. Mobile homes, recreational vehicles, and boating facilities were heavily damaged. One mobile home was completely destroyed, with debris from the structure scattered. Power poles were snapped, and many trees were snapped along the path.[39][35][57] |

| EF0 | Clarendon | Donley | TX | 34.9348°N 100.9031°W | 23:51–23:52 | 0.95 mi (1.53 km) | 40 yd (37 m) | Brief, rain-wrapped tornado damaged several homes and sheds in town. Around ten homes sustained shingle damage to roofs, and several trees were downed. This tornado occurred simultaneously with and just east of the Clarendon–Howardwick EF2 tornado.[39][35][58] |

| EFU | E of Lazare | Hardeman | TX | 34.28°N 99.965°W | 01:41 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 50 yd (46 m) | A brief tornado was observed by trained spotters. No damage occurred.[59] |

| EFU | N of Goodlett | Hardeman | TX | 34.3834°N 99.88°W | 02:00 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 30 yd (27 m) | A brief tornado was reported by a trained spotter. No damage occurred.[60] |

| EFU | WNW of Eldorado | Jackson | OK | 34.49°N 99.7704°W | 02:15 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 30 yd (27 m) | A brief tornado was reported by two trained spotters. No damage occurred.[61] |

| EFU | S of McQueen | Harmon | OK | 34.583°N 99.70°W | 02:29 | 0.2 mi (0.32 km) | 20 yd (18 m) | A brief tornado was observed by a trained spotter. No damage was reported, however, power flashes were observed with this tornado.[62] |

| EF1 | S of Reed | Greer | OK | 34.767°N 99.668°W | 02:49–02:50 | 0.7 mi (1.1 km) | 50 yd (46 m) | A tornado developed near the community of Russell and moved to the north-northeast. One shed, two tractors, and the porch of a home were damaged at a farm. Two sheds were destroyed at another farm. Some debris was scattered for 1.5 mi (2.4 km).[63] |

| EF2 | NNW of Fowler to WNW of Ensign | Gray | KS | 37.4986°N 100.2752°W | 03:22–03:38 | 12.15 mi (19.55 km) | 100 yd (91 m) | Near the start of the path, the tornado overturned a pivot irrigation sprinkler. As the tornado moved north-northeast, it snapped eight sturdy power poles, and destroyed a small grain bin. Another pivot irrigation sprinkler was overturned before the tornado lifted. Some ground scouring was observed in farm fields along the path.[39][64] |

See also

Notes

- All dates are based on the local time zone where the tornado touched down; however, all times are in Coordinated Universal Time for consistency.

References

- Peter Mullinax (March 22, 2021). "Central Rockies & High Plains March Snowstorm: (3/13 - 3/15)". www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- "Global Catastrophe Recap – March 2021" (PDF). AON Benfield. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- "Biggest total from record-shattering snowstorm tops 50 inches". AccuWeather. March 15, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- "Winter Storm Xylia Shuts Down Interstates; Tens of Thousands Lose Power". The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- Matt Sparx (March 15, 2021). "WINTER STORM XYLIA BECOMES DENVER'S 4TH ALL TIME LARGEST". New Country 99.1. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/06/2021 at 18 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 6, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/07/2021 at 12 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 7, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/08/2021 at 09 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/09/2021 at 15 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/10/2021 at 09 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/10/2021 at 15 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/11/2021 at 12 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 11, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/12/2021 at 15 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/13/2021 at 15 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/14/2021 at 00 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/14/2021 at 15 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/14/2021 at 21 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/15/2021 at 15 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 15, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/15/2021 at 21 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 15, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/16/2021 at 18 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/17/2021 at 03 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 17, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- "WPC surface analysis valid for 03/17/2021 at 12 UTC". wpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Weather Prediction Center. March 17, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- "How Colorado is preparing for this weekend's potentially historic snowstorm". KMGH. March 11, 2021.

- O’Brien, Brendan (March 13, 2021). "Dangerous spring snow storm takes aim at U.S. Rockies, High Plains". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- "WYDOT urges motorists to stay safe during upcoming winter storm". Wyoming Tribune Eagle. March 12, 2021.

- "Winter Storm Xylia Traps Motorists on Colorado Highways; Travel Remains Treacherous in Wyoming, Nebraska". The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- "Mar 13, 2021 1300 UTC Day 1 Convective Outlook". Storm Prediction Center. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- "Colorado blizzard is now Denver's 4th largest storm on record". The Denver Post. 15 March 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- Blues-Kings game postponed after team can't make it to LA, KSDK, March 15, 2021

- "Major Roads Still Closed After Winter Storm Xylia Buries Wyoming, Colorado". The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- "Storm Prediction Center Today's Storm Reports". www.spc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- "Tornado Warning". Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Forecast Office in Amarillo, Texas. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- "Tornado Warning". Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Forecast Office in Amarillo, Texas. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- "Tornado Warning". Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Forecast Office in Amarillo, Texas. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- NWS Damage Survey for 3/13/21 Tornado Event Update #3 (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Amarillo, Texas. March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- https://apps.dat.noaa.gov/StormDamage/DamageViewer/NOAA Damage Viewer. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Dodge City, Kansas. March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- Tornado Event Reports: March 13, 2021, National Centers for Environmental Information

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- "ArcGIS Web Application". apps.dat.noaa.gov. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- NWS Damage Survey for 03/13/21 Tornado Event (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Lubbock, Texas. March 17, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Storm Events Database March 13, 2021 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 16, 2021.