Treaty of Tientsin

The Treaty of Tientsin, also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several documents signed at Tianjin (then romanized as Tientsin) in June 1858. The Qing dynasty, Russian Empire, Second French Empire, United Kingdom, and the United States were the parties involved. These treaties, counted by the Chinese among the so-called unequal treaties, opened more Chinese ports to foreign trade, permitted foreign legations in the Chinese capital Beijing, allowed Christian missionary activity, and effectively legalized the import of opium. They ended the first phase of the Second Opium War, which had begun in 1856 and were ratified by the Emperor of China in the Convention of Peking in 1860, after the end of the war.

| Treaty of Tientsin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

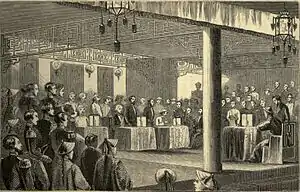

Signing of the Anglo-Chinese treaty of Tianjin | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 天津條約 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 天津条约 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Dates

The Xianfeng Emperor authorized negotiations for the treaty on May 29, 1858.[1] His chief representatives were the Manchu Guiliang (桂良) and the Mongol Huashana (花沙納). The Russian treaty was negotiated by Yevfimiy Putyatin and finalized on June 13;[2] the American treaty was negotiated by William Bradford Reed and finalized on June 18;[3] the British treaty was negotiated by James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, and finalized on June 26;[4] and the French treaty was negotiated by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gros and finalized on June 27.[5]

American involvement

Following the pattern set by the great powers of Europe, the United States took on a protectionist stance, built up its navy, and tried to create a mercantile empire. The United States was one of the leading "treaty powers" in China, forcing open a total of 23 foreign concessions from the Chinese government. While it is often noted that the United States did not control any settlements in China, it shared British land grants and was actually invited to take land in Shanghai but refused because the land was thought to be disadvantageous.[6]

Terms

Major points

- Russia, which had previously been limited to trading at designated border posts, received the right to trade with the treaty ports by sea.[7] Most-favored nation clauses in each treaty[8][9][10][11] further ensured that all concessions were shared by the four powers.

- Guangzhou[lower-alpha 1] and the four treaty ports opened to foreign trade and residence by the Treaty of Nanjing were joined by Tainan,[lower-alpha 2][7] Haikou,[lower-alpha 3][7] Shantou,[lower-alpha 4][12] Haicheng,[lower-alpha 5][13] Penglai,[lower-alpha 6][13] Tamsui,[lower-alpha 7][14] and (notionally) Nanjing.[lower-alpha 8][14] The ports at Haicheng and Penglai being found inadequate for European vessels, their status was later extended to nearby Yantai and Yingkou, effectively opening another two ports.

- China was forbidden from considering Russian Orthodox,[15] Protestant,[16] and Roman Catholic Christianity,[16] whether practiced by foreigners or Chinese converts,[16] to be a harmful superstition. All laws, regulations, and practices limiting its observance became null and void everywhere in the country.[17]

- The extraterritoriality of American citizens[18] and Russian,[19] British,[20] and French subjects[21] was reaffirmed. They further received the right to travel throughout the Qing Empire for pleasure or business so long as they possessed a valid passport,[22][23] but the Qing Empire was able to prevent them from lawfully residing in the interior with extraterritoriality.[24]

- The Qing Empire permitted foreign vessels to navigate on the Yangtze River[25] but established that no legal trade would be permitted with areas held by the Taiping Rebellion until their reconquest.[22][14] Foreign trade was to be limited to Zhenjiang,[lower-alpha 9] pledged to be opened within the year, and a further three ports to be opened after the suppression of the Taipings. This clause was later used to establish treaty ports at Wuhan[lower-alpha 10] and Jiujiang.[lower-alpha 11]

- The four nations gained the right to station permanent diplomatic legations in Beijing,[lower-alpha 12][26] which had previously been a closed city. The Russians' ecclesiastical mission in Beijing was also exempted from its previous restrictions.[29]

- China was forbidden from using the character 夷 (understood to mean "barbarian")[30] in official documents to refer to officials, subjects, or citizens of the four nations.[30]

- China was forbidden from establishing or permitting any further monopolies or cartels over its domestic trade.[31]

- Addenda to the treaties settled China's duties and tariffs on terms advantageous to the victors and pledged the Qing Empire would pay an indemnity of 6,000,000 taels of silver: 2 million to France, 2 million to Britain for military expenses, and 2 million as compensation to British merchants.

Definitions

The Treaties of Tientsin use several words that have somewhat ambiguous meanings. For example, the words "settlement" and "concession" can often be confused. The term "settlement" refers to a parcel of land, leased to a foreign power, which is composed of both foreign and national peoples, and governed by locally elected foreigners. The term "concession" refers to a long-term lease of land to a foreign power, under which the foreign nation has complete control of the land, which is governed by consular representatives.[32]

See also

Notes

- Then known as "Canton".[7][12][13][14]

- Then known as "Taiwan-fu",[7] "Tai-wan",[12] "Taiwan",[13] or "Taïwan".[14]

- Then known as "Tsion-chou",[7] "Kiungchow"[13] or "Kiung-Tchau".[14]

- Then known as "Chau-chau",[12] "Swatow",[12] "Chawchow",[13] and "Chaou-Chaou".[14]

- Then known as "Newchwang".[13]

- Then known as "Tǎngchow"[13] or "Tan-Tchau".[14]

- Then known as "Taashwi".[14]

- Then known as "Nanking"[13] or "Nankin".[14]

- Then known as "Chinkiang".[25]

- Specifically, the formerly separate city of Hankou north and west of the confluence of the Han and Yangtze Rivers.

- The third port was Nanjing, which had been opened by the French treaty[14] and the most-favored nation clauses of the others.[8][9][10]

- Then known as "Peking"[26] or "Pekin".[27][28]

References

Citations

- Wang, Dong. China's Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History. Lexington Books, 2005, p. 16.

- Russian treaty (1858), Art. 12.

- American treaty (1858), Art. XXX.

- British treaty (1858), Art. LVI.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 42.

- Johnstone (1937), p. 945.

- Russian treaty (1858), Art. 3.

- Russian treaty (1858), Art. 4 & 12.

- American treaty (1858), Art. XV & XXX.

- British treaty (1858), Art. XXIV & LIV.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 2, 9, & 40.

- American treaty (1858), Art. XIV.

- British treaty (1858), Art. XI.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 6.

- Russian treaty (1858), Art. 8.

- American treaty (1858), Art. XXIX.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 13.

- American treaty (1858), Art. XI.

- Russian treaty (1858), Art. 7.

- British treaty (1858), Art. XV & XVI.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 38 & 39.

- British treaty (1858), Art. IX.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 7.

- Cassel (2012), p. 62.

- British treaty (1858), Art. X.

- British treaty (1858), Art. III.

- American treaty (1858), Art. II.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 2.

- Russian treaty (1858), Art. 10.

- British treaty (1858), Art. LI.

- French treaty (1858), Art. 14.

- Johnstone (1937), p. 942.

Bibliography

- Chan, Mitchell. "Rule of Law and China's Unequal Treaties: Conceptions of the Rule of Law and Its Role in Chinese International Law and Diplomatic Relations in the Early Twentieth Century." Penn History Review 25.2 (2018): 2. online

- Bloch, Kurt (May 1939). "The Basic Conflict over Foreign Concessions in China". Far Eastern Survey. 8 (10): 111–116. doi:10.2307/3023092. JSTOR 3023092.

- Cassel, Pär (2012), Grounds of Judgment, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Johnstone, William C. (October 1937). "International Relations: The Status of Foreign Concessions and Settlements in the Treaty Ports of China". The American Political Science Review. 31 (5): 942–8. doi:10.2307/1947920. JSTOR 1947920. S2CID 147155580.

Primary sources

- Bruce, James; et al. (26 June 1858), Peace Treaty between the Queen of Great Britain and the Emperor of China, Tianjin

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - "Treaties of Tianjin, 1858 and 1860", 600 Years of Urban Planning in and around Tianjin, Cornell University, 2004, archived from the original on 2010-06-21.

- Reed, William Bradford; et al. (18 June 1858), Treaty of Peace, Amity, and Commerce between the United States of America and China, Tianjin

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - France: Treaty of Tientsin [Tianjin], 1858

- Russia: Treaty of Tientsin [Tianjin], 1858

External links

- American, British, French, and Russian treaties at China Foreign Relations (in English)

- American treaty in United States Statutes at Large, Vol. XII (1863)

- British treaty in Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Vol. XXXIII: Correspondence Relative to the Earl of Elgin's Special Missions to China and Japan... (1859)