Ailanthus altissima

Ailanthus altissima /eɪˈlænθəs ælˈtɪsɪmə/ ay-LAN-thəss al-TIH-sim-ə,[3] commonly known as tree of heaven, Ailanthus, varnish tree, copal tree, stinking sumac, Chinese sumac, paradise tree,[4] or in Chinese as chouchun (Chinese: 臭椿; pinyin: chòuchūn), is a deciduous tree in the family Simaroubaceae.[1] It is native to northeast and central China, and Taiwan. Unlike other members of the genus Ailanthus, it is found in temperate climates rather than the tropics.

| Tree of heaven[1] | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Large specimen growing in a park in Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Simaroubaceae |

| Genus: | Ailanthus |

| Species: | A. altissima |

| Binomial name | |

| Ailanthus altissima | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The tree grows rapidly, and is capable of reaching heights of 15 metres (50 ft) in 25 years. While the species rarely lives more than 50 years, some specimens exceed 100 years of age.[5] Its suckering ability allows this tree to clone itself indefinitely.[6] It is considered a noxious weed and vigorous invasive species,[1] and one of the worst invasive plant species in Europe and North America.[7] In 21st-century North America, the invasiveness of the species has been compounded by its role in the life cycle of the also destructive and invasive spotted lanternfly.[8][9]

Description

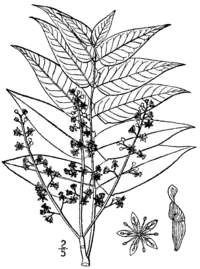

Ailanthus altissima is a medium-sized tree that reaches heights between 17 and 27 m (60 and 90 ft) with a diameter at breast height of about 1 m (3 ft).[10] The bark is smooth and light grey, often becoming somewhat rougher with light tan fissures as the tree ages. The twigs are stout, smooth to lightly pubescent, and reddish or chestnut in color. They have lenticels and heart-shaped leaf scars (i.e., a scar left on the twig after a leaf falls) with many bundle scars (i.e., small marks where the veins of the leaf once connected to the tree) around the edges. The buds are finely pubescent, dome-shaped, and partially hidden behind the petiole, though they are completely visible in the dormant season at the sinuses of the leaf scars.[11] The branches are light to dark gray in color, smooth, lustrous, and contain raised lenticels that become fissures with age. The ends of the branches become pendulous. All parts of the plant have a distinguishing strong odor that is often likened to peanuts, cashews,[4] or rotting cashews.[12]

The leaves are large, odd- or even-pinnately compound on the stem. They range in size from 30 to 90 centimetres (1 to 3 ft) in length and contain 10–41 leaflets organised in pairs, with the largest leaves found on vigorous young sprouts. When they emerge in the spring, the leaves are bronze, then quickly turn from medium to dark green as they grow.[13] The rachis is light to reddish-green with a swollen base. The leaflets are ovate-lanceolate with entire margins, somewhat asymmetric and occasionally not directly opposite to each other. Each leaflet is 5–18 cm (2–7 in) long and 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) wide. They have a long, tapering end, while the bases have two to four teeth, each containing one or more glands at the tip.[11] The leaflets' upper sides are dark green in color with light green veins, while the undersides are a more whitish green. The petioles are 5–12 millimetres (0.2–0.5 in) long.[4] The lobed bases and glands distinguish it from similar sumac species.

The flowers are small and appear in large panicles up to 50 cm (20 in) in length at the end of new shoots. The individual flowers are yellowish green to reddish in color, each with five petals and sepals.[10][4] The sepals are cup-shaped, lobed and united while the petals are valvate (i.e., they meet at the edges without overlapping), white and hairy towards the inside.[11][14][15] They appear from mid-April in the south of its range to July in the north. A. altissima is dioecious, with male and female flowers being borne on different individuals. Male trees produce three to four times as many flowers as the females, making the male flowers more conspicuous. Furthermore, the male plants emit a foul-smelling odor while flowering to attract pollinating insects. Female flowers contain 10 (or rarely five through abortion) sterile stamens (stamenoids) with heart-shaped anthers. The pistil is made up of five free carpels (i.e., they are not fused), each containing a single ovule. Their styles are united and slender with star-shaped stigmata.[11][14] The male flowers are similar in appearance, but they lack a pistil and the stamens do function, each being topped with a globular anther and a glandular green disc.[11] The fruits grow in clusters; similar to the ash tree (Fraxinus excelsior), the fruits ripen to a bright reddish-brown color in September.[16] A fruit cluster may contain hundreds of seeds.[7] The seeds borne on the female trees are 5 mm (0.2 in) in diameter and each is encapsulated in a samara that is 2.5 cm (1 in) long and 1 cm (0.4 in) broad, appearing July through August, but can persist on the tree until the next spring. The samara is large and twisted at the tips, making it spin as it falls, assisting wind dispersal,[10][4] and aiding buoyancy for long-distance dispersal through hydrochory.[17] Primary wind dispersal and secondary water dispersal are usually positively correlated in A. altissima, since most morphological characteristics of samaras affect both dispersal modes in the same way – except for the width of the samaras, which in contrast affects both types of dispersal in opposing ways, allowing differentiation in the dispersal strategies of this tree.[18] The females can produce huge numbers of seeds, normally around 30,000 per kg,[10] and fecundity can be estimated nondestructively through measurements of diameter at chest height.[17]

History

In China, the tree of heaven has a long and rich history. It was mentioned in the oldest extant Chinese dictionary and listed in many Chinese medical texts for its purported curative ability. The roots, leaves, and bark are used in traditional Chinese medicine, primarily as an astringent. The tree has been grown extensively both in China and abroad as a host plant for the ailanthus silkmoth, a moth involved in silk production.[1] Ailanthus has become a part of Western culture, as well, with the tree serving as the central metaphor and subject matter of the best-selling American novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith.

The tree was first brought from China to Europe in the 1740s and to the United States in 1784. It was one of the first trees brought west during a time when chinoiserie was dominating European arts and was initially hailed as a beautiful garden specimen. However, enthusiasm soon waned after gardeners became familiar with its suckering habits and its foul odor. Despite this, it was used extensively as a street tree during much of the 19th century. Outside Europe and the United States, the plant has been spread to many other areas beyond its native range, and is regarded internationally as a noxious weed.[1] In many countries, it is an invasive species due to its ability both to colonise disturbed areas quickly and to suppress competition with allelopathic chemicals.[1] The tree also resprouts vigorously when cut, making its eradication difficult and time-consuming. This has led to its being called "tree of hell" among gardeners and conservationists.[19]

Taxonomy

The first Western scientific descriptions of the tree of heaven were made shortly after it was introduced to Europe by French Jesuit Pierre Nicholas d'Incarville, who had sent seeds from Peking via Siberia to his botanist friend Bernard de Jussieu in the 1740s. The seeds sent by d'Incarville were thought to be from the economically important and similar-looking Chinese varnish tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), which he had observed in the lower Yangtze region, rather than the tree of heaven. D'Incarville attached a note indicating this, which caused much taxonomic confusion over the next few decades. In 1751, Jussieu planted a few seeds in France and sent others on to Philip Miller, the superintendent at the Chelsea Physic Garden, and to Philip C. Webb, the owner of an exotic plant garden in Busbridge, England.[11]

Confusion in naming began when the tree was described by all three men with three different names. In Paris, Linnaeus gave the plant the name Rhus succedanea, while it was known commonly as grand vernis du Japon. In London, the specimens were named by Miller as Toxicodendron altissima, and in Busbridge, it was dubbed in the old classification system as Rhus Sinese foliis alatis. Records exist from the 1750s of disputes over the proper name between Philip Miller and John Ellis, curator of Webb's garden in Busbridge. Rather than the issue being resolved, more names soon appeared for the plant: Jakob Friedrich Ehrhart observed a specimen in Utrecht in 1782 and named it Rhus cacodendron.[11]

Light was shed on the taxonomic status of Ailanthus in 1788 when René Louiche Desfontaines observed the samaras of the Paris specimens, which were still labelled Rhus succedanea, and came to the conclusion that the plant was not a sumac. He published an article with an illustrated description and gave it the name Ailanthus glandulosa, placing it in the same genus as the tropical species then known as A. integrifolia (white siris, now A. triphysa). The name is derived from the Ambonese word ailanto, meaning "heaven-tree" or "tree reaching for the sky".[11][20] The specific glandulosa, referring to the glands on the leaves, persisted until as late as 1957, but it was ultimately made invalid as a later homonym at the species level.[11] The current species name comes from Walter T. Swingle, who was employed by the United States Department of Plant Industry. He decided to transfer Miller's older specific name into the genus of Desfontaines, resulting in the accepted name Ailanthus altissima.[21] Altissima is Latin for "tallest",[22] and refers to the sizes the tree can reach. The plant is sometimes incorrectly cited with the specific epithet in the masculine (glandulosus or altissimus), which is incorrect since botanical, like Classical Latin, treats most tree names as feminine.

The three varieties of A. altissima are:

- Ailanthus altissima var. altissima, which is the type variety and is native to mainland China

- Ailanthus altissima var. tanakai, which is endemic to northern Taiwan highlands: It differs from the type in having yellowish bark, odd-pinnate leaves that are also shorter on average at 45 to 60 cm (18 to 24 in) long with only 13–25 scythe-like leaflets.[23][24][25] It is listed as endangered in the IUCN Red List of threatened species due to loss of habitat for building and industrial plantations.[26]

- Ailanthus altissima var. sutchuenensis, which differs in having red branchlets[23][24]

Distribution and habitat

Ailanthus altissima is native to northern and central China,[1] Taiwan[27] and northern Korea.[28] It was historically widely distributed, and the fossil record indicates clearly that it was present in North America as recently as the middle Miocene.[29] In Taiwan it is present as var. takanai.[26] In China it is native to every province except Gansu, Heilongjiang, Hainan, Jilin, Ningxia, Qinghai, Xinjiang. It is also not found in Tibet.[23] It has been introduced in many regions across the world, and is now found on every continent except Antarctica.[1][19]

The tree prefers moist and loamy soils but is adaptable to a very wide range of soil conditions and pH values. It is drought-hardy, but not tolerant of flooding. It also does not tolerate deep shade.[10] In China, it is often found in limestone-rich areas.[24] The tree of heaven is found within a wide range of climatic conditions.[10] In its native range, it is found at high altitudes in Taiwan[26] and lower ones in mainland China.[11] It is present virtually everywhere in the U.S., but especially in arid regions bordering the Great Plains, very wet regions in the southern Appalachians, cold areas of the lower Rocky Mountains, and throughout much of the California Central Valley, forming dense thickets that displace native plants.[1] Prolonged cold and snow cover cause dieback, although the trees resprout from the roots.[10]

As an exotic plant

The earliest introductions of A. altissima to countries outside of its native range were to the southern areas of Korea and to Japan. The tree may be native to these areas, but the tree is generally agreed to be a very early introduction.[30] Within China, it has also been naturalised beyond its native range in areas such as Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang.[24]

In 1784, not long after Jussieu had sent seeds to England, some were forwarded to the United States by William Hamilton, a gardener in Philadelphia. In both Europe and America, it quickly became a favoured ornamental, especially as a street tree, and by 1840, it was available in most nurseries.[11][20] The tree was separately brought to California in the 1890s by Chinese immigrants who came during the California Gold Rush. It has escaped cultivation in all areas where it was introduced, but most extensively in the United States.[27] It has naturalised across much of Europe, including Germany,[31] Austria, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, the Pannonian region (i.e. southeastern Central Europe around the Danube River basin from Austria, Slovakia, and Hungary south to the Balkan ranges) and most countries of the Mediterranean Basin.[28] In Montenegro[32] and Albania[33][34] A. altissima is widespread in both rural and urban areas, and while in the first it was introduced as an ornamental plant, it very soon invaded native ecosystems with disastrous results and became an invasive species.[32] Ailanthus has also been introduced to Argentina,[27] Australia (where it is a declared weed in New South Wales and Victoria),[35] New Zealand (where it is listed under the National Pest Plant Accord and is classed an "unwanted organism"),[36] the Middle East, and in some countries in South Asia such as Pakistan.[37] In South Africa, it is listed as an invasive species that must be controlled, or removed and destroyed.[38]

In North America, A. altissima is present from Massachusetts in the east, west to southern Ontario, southwest to Iowa, south to Texas, and east to the north of Florida. In the west, it is found from New Mexico west to California and north to Washington.[10][27] In the east of its range, it grows most extensively in disturbed areas of cities, where it was long ago present as a planted street tree.[11][27] It also grows along roads and railways. For example, a 2003 study in North Carolina found the tree of heaven was present on 1.7% of all highway and railroad edges in the state, and had been expanding its range at the rate of 4.76% counties per year.[39] Similarly, another study conducted in southwestern Virginia determined that the tree of heaven is thriving along roughly 30% of the state's interstate highway system length or mileage.[40] It sometimes enters undisturbed areas as well, and competes with native plants.[27] In western North America, it is most common in mountainous areas around old dwellings and abandoned mining operations.[41][42] It is classified as a noxious or invasive plant on National Forest System lands and in many states[43] because its prolific seed production, high germination rate, and capacity to regrow from roots and root fragments enable A. altissima[44] to out-compete native species. For this reason, control measures on public lands[45] and private property[46] are advised where A. altissima has naturalised.

Ecology

The tree of heaven is an opportunistic plant that thrives in full sun and disturbed areas. It spreads aggressively both by seeds and vegetatively by root sprouts, re-sprouting rapidly after being cut.[1][10] It is considered a shade-intolerant tree and cannot compete in low-light situations,[47] though it is sometimes found competing with hardwoods. Such competition indicates it was present at the time the stand was established.[10] On the other hand, a study in an old-growth hemlock–hardwood forest in New York found that Ailanthus was capable of competing successfully with native trees in canopy gaps where only 2-15% of full sun was available. The same study characterised the tree as using a "gap-obligate" strategy to reach the forest canopy, meaning it grows rapidly during a very short period rather than growing slowly over a long period.[48] It is a short-lived tree in any location and rarely lives more than 50 years.[10] Among tree species, Ailanthus is among the most tolerant of pollution, including sulfur dioxide, which it absorbs in its leaves. It can withstand cement dust and fumes from coal tar operations, as well as resist ozone exposure relatively well. Furthermore, high concentrations of mercury have been found built up in tissues of the plant.[27]

Ailanthus has been used to re-vegetate areas where acid mine drainage has occurred and it has been shown to tolerate pH levels as low as 4.1 (approximately that of tomato juice). It can withstand very low phosphorus levels and high salinity levels. The drought tolerance of the tree is strong due to its ability to effectively store water in its root system.[27] It is frequently found in areas where few trees can survive. The roots are also aggressive enough to cause damage to subterranean sewers and pipes.[11] Along highways, it often forms dense thickets in which few other tree species are present, largely due to the toxins it produces to prevent competition.[27] The roots are poisonous to people.[49]

.jpg.webp)

Ailanthus produces an allelopathic chemical called ailanthone, which inhibits the growth of other plants.[50] The inhibitors are strongest in the bark and roots, but are also present in the leaves, wood and seeds of the plant. One study showed that a crude extract of the root bark inhibited 50% of a sample of garden cress (Lepidium sativum) seeds from germinating. The same study tested the extract as an herbicide on garden cress, redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti), yellow bristlegrass (Setaria pumila), barnyard grass (Echinochloa crusgalli), pea (Pisum sativum cv. Sugar Snap), and maize (Zea mays cv. Silver Queen). It proved able to kill nearly 100% of seedlings with the exception of velvetleaf, which showed some resistance.[51] Another experiment showed that a water extract of the chemical was either lethal or highly damaging to 11 North American hardwoods and 34 conifers, with the white ash (Fraxinus americana) being the only plant not adversely affected.[52] The chemical does not, however, affect the tree of heaven's own seedlings, indicating that A. altissima has a defence mechanism to prevent autotoxicity.[50] Resistance in various plant species has been shown to increase with exposure. Populations without prior exposure to the chemicals are most susceptible to them. Seeds produced from exposed plants have also been shown to be more resistant than their unexposed counterparts.[53]

The tree of heaven is a very rapidly growing tree, possibly the fastest-growing tree in North America.[43] Growth of 1 to 2 metres (3 to 7 ft) per year for the first four years is considered normal. Shade considerably hampers growth rates. Older trees, while growing much slower, still do so faster than other trees. Studies found that Californian trees grew faster than their East Coast counterparts, and American trees in general grew faster than Chinese ones.[43]

In northern Europe the tree of heaven was not considered naturalised in cities until after the Second World War. This has been attributed to the tree's ability to colonise areas of rubble of destroyed buildings where most other plants would not grow.[28] In addition, the warmer microclimate in cities offers a more suitable habitat than the surrounding rural areas; it is thought that the tree requires a mean annual temperature of 8 °C (46 °F) to grow well, which limits its spread in more northern and higher-altitude areas. For example, one study in Germany found the tree of heaven growing in 92% of densely populated areas of Berlin, 25% of its suburbs and only 3% of areas outside the city altogether.[28] In other areas of Europe this is not the case as climates are mild enough for the tree to flourish. It has colonised natural areas in Hungary, for example, and is considered a threat to biodiversity at that country's Aggtelek National Park.[28]

Several species of Lepidoptera use the leaves of Ailanthus as food, including the Indian moon moth (Actias selene) and the common grass yellow (Eurema hecabe). In North America the tree is the host plant for the ailanthus webworm (Atteva aurea), though this ermine moth is native to Central and South America and originally used other members of the mostly tropical Simaroubaceae as its hosts.[54] In the US, it has been found to host the brown marmorated stink bug and the Asiatic shot-hole borer.[19] The spotted lanternfly (L. delicatula), relies on the metabolites of A. altissima for the completion of its life cycle and the pervasiveness of A. altissima is seen as a driving factor in L. delicatula's invasive spread outside of China.[55][56] In its native range A. altissima is associated with at least 32 species of arthropods and 13 species of fungi.[24]

In North America, the leaves of Ailanthus are sometimes attacked by Aculops ailanthii, a mite in the family Eriophyidae. Leaves infested by the mite begin to curl and become glossy, reducing their ability to function. Therefore, this species has been proposed as a possible biocontrol for Ailanthus in the Americas.[57] Research from September 2020 indicates a verticillium wilt, caused by Verticillium nonalfalfae, may function as a biological control for A. altissima,[58] with the weevil Eucryptorrhynchus brandti serving as a vector.[59]

Due to the tree of heaven's weedy habit, landowners and other organisations often resort to various methods of control to keep its populations in check. For example, the city of Basel in Switzerland has an eradication program for the tree.[28] It can be very difficult to eradicate, however. Means of eradication can be physical, thermal, managerial, biological or chemical. A combination of several of these can be most effective, though they must of course be compatible. All have some positive and negative aspects, but the most effective regimen is generally a mixture of chemical and physical control. It involves the application of foliar or basal herbicides to kill existing trees, while either hand pulling or mowing seedlings to prevent new growth.[60][note 1]

Uses

In addition to its use as an ornamental plant, the tree of heaven is also used for its wood and as a host plant to feed silkworms of the moth Samia cynthia, which produces silk that is stronger and cheaper than mulberry silk, although with inferior gloss and texture.[1] It is also unable to take dye. This type of silk is known under various names: "pongee", "eri silk", and "Shantung silk", the last name being derived from Shandong in China where this silk is often produced. Its production is particularly well known in the Yantai region of that province. The moth has also been introduced in the United States.[11]

The pale yellow, close-grained, and satiny wood of Ailanthus has been used in cabinet work.[1][61] It is flexible and well-suited to the manufacture of kitchen steamers, which are important in Chinese cuisine for cooking mantou, pastries, and rice. Zhejiang in eastern China is most famous for producing these steamers.[11] The plant is also considered a good source of firewood across much of its range, as it is moderately hard and heavy, yet readily available.[62] The wood is also used to make charcoal for culinary purposes.[63] However, there are problems with using the wood as lumber; because the trees exhibit rapid growth for the first few years, the trunk has uneven texture between the inner and outer wood, which can cause the wood to twist or crack during drying. Techniques have been developed for drying the wood so as to prevent this cracking, allowing it to be commercially harvested. Although the live tree tends to have very flexible wood, the wood is quite hard once properly dried.[64]

Cultivation

Tree of heaven is a popular ornamental tree in China and valued for its tolerance of difficult growing conditions.[24] It was once very popular in cultivation in both Europe and North America, but this popularity dropped, especially in the United States, due to the disagreeable odor of its blossoms and the weediness of its habit. The problem of odor was previously avoided by only selling pistillate plants since only males produce the smell, but a higher seed production also results.[20] Michael Dirr, a noted American horticulturalist and professor at the University of Georgia, reported meeting, in 1982, a grower who could not find any buyers. He further writes (his emphasis):

For most landscaping conditions, it has no value as there are too many trees of superior quality; for impossible conditions this tree has a place; selection could be made for good habit, strong wood and better foliage which would make the tree more satisfactory; I once talked with an architect who tried to buy Ailanthus for use along polluted highways but could not find an adequate supply [...]

— Michael A. Dirr, Manual of Woody Landscape Plants[65]

In Europe, however, the tree is still used in the garden to some degree as its habit is generally not as invasive as it is in America. In the United Kingdom it is especially common in London squares, streets, and parks, though it is also frequently found in gardens of southern England and East Anglia. It becomes rare in the north, occurring only infrequently in southern Scotland. It is also rare in Ireland.[66] In Germany the tree is commonly planted in gardens.[31] The tree has furthermore become unpopular in cultivation in the west because it is short-lived and that the trunk soon becomes hollow, making trees more than two feet in diameter unstable in high winds.[61]

A few cultivars exist, but they are not often sold outside of China and probably not at all in North America:

- 'Hongye' – The name is Chinese and means "red leaves". As the name implies it has attractive vivid red foliage[67]

- 'Thousand Leaders'[67]

- 'Metro' – A male cultivar with a tighter crown than usual and a less weedy habit[68]

- 'Erythrocarpa' – The fruits are a striking red[68]

- 'Pendulifolia' – Leaves are much longer and hang elegantly[68]

Traditional medicine

Nearly every part of A. altissima has had various uses in Chinese traditional medicine,[11] although there is no high-quality clinical evidence that it has an effect on any disease.

A tincture of the root bark was thought useful by American herbalists in the 19th century.[14] It contains phytochemicals, such as quassin and saponin, and ailanthone.[69] The plant may be mildly toxic.[1] The noxious odours have been associated with nausea and headaches, and with contact dermatitis reported in both humans and sheep, which developed weakness and paralysis. It contains a quinone irritant, 2,6-dimethoxybenzoquinone, as well as quassinoids.[69]

Culture

China

In addition to the tree of heaven's various uses, it has also been a part of Chinese culture for many centuries and has more recently attained a similar status in the west. Within the oldest extant Chinese dictionary, the Erya, written in the 3rd century BCE, the tree of heaven is mentioned second among a list of trees. It was mentioned again in a materia medica compiled during the Tang dynasty in 656 CE. Each work favoured a different character, however, and there is still some debate in the Chinese botanical community as to which character should be used. The current name, chouchun (Chinese: 臭椿; pinyin: chòuchūn), means "stinking tree", and is a relatively new appellation. People living near the lower Yellow River know it by the name chunshu (simplified Chinese: 椿树; traditional Chinese: 椿樹; pinyin: chūnshù), meaning "spring tree". The name stems from the fact that A. altissima is one of the last trees to come out of dormancy, and as such its leaves coming out would indicate that winter was truly over.[11]

In Chinese literature, Ailanthus is often used for two rather extreme metaphors, with a mature tree representing a father and a stump being a spoiled child. This manifests itself occasionally when expressing best wishes to a friend's father and mother in a letter, where one can write "wishing your Ailanthus and daylily are strong and happy", with ailanthus metaphorically referring to the father and daylily to the mother. Furthermore, one can scold a child by calling him a "good-for-nothing Ailanthus stump sprout", meaning the child is irresponsible. This derives from the literature of Zhuangzi, a Taoist philosopher, who referred to a tree that had developed from a sprout at the stump and was thus unsuitable for carpentry due to its irregular shape. Later scholars associated this tree with Ailanthus and applied the metaphor to children who, like stump sprouts of the tree, will not develop into a worthwhile human being if they don't follow rules or traditions.[70]

United States

The 1943 book A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith uses the tree of heaven as its central metaphor, using it as an analogy for the ability to thrive in a difficult environment. At that time as well as now, Ailanthus was common in neglected urban areas.[20][71] She writes:

There's a tree that grows in Brooklyn. Some people call it the Tree of Heaven. No matter where its seed falls, it makes a tree which struggles to reach the sky. It grows in boarded up lots and out of neglected rubbish heaps. It grows up out of cellar gratings. It is the only tree that grows out of cement. It grows lushly...survives without sun, water, and seemingly earth. It would be considered beautiful except that there are too many of it.

— A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Introduction

In William Faulkner's novel, Sanctuary, a "heaven-tree" stands outside the Jefferson jail, where Lee Goodwin and a "negro murderer" are incarcerated. The tree is associated with the black prisoner's despair in the face of his impending execution and the spirituals that he sings in chorus with other black people who keep a sort of vigil in the street below:

...they sang spirituals while white people slowed and stopped in the leafed darkness that was almost summer, to listen to those who were sure to die and him who was already dead singing about heaven and being tired; or perhaps in the interval between songs a rich, sourceless voice coming out of the high darkness where the ragged shadow of the heaven-tree which snooded the street lamp at the corner fretted and mourned: "Fo days mo! Den dey ghy stroy de bes ba'yton singer in nawth Mississippi!"[72] Upon the barred and slitted wall the splotched shadow of the heaven-tree shuddered and pulsed monstrously in scarce any wind; rich and sad, the singing fell behind.[73]

In the 2013 book Teardown: Memoir of a Vanishing City by Gordon Young, the tree is referenced in a description of the Carriage Town neighborhood in Flint, Michigan.

Festive Victorian-era homes in various stages of restoration battled for supremacy with boarded-up firetraps and overgrown lots landscaped with weeds, garbage, and "ghetto palms," a particularly hardy invasive species known more formally as Ailanthus altissima, or the tree of heaven, perhaps because only God can kill the things. Around the corner, business was brisk at a drug house where residents and customers alike weren't above casually taking a piss in the driveway.[74]

Ailanthus is also sometimes counter-nicknamed "tree from hell" due to its prolific invasiveness and the difficulty in eradicating it.[71][75] In certain parts of the United States, the species has been nicknamed the "ghetto palm" because of its propensity for growing in the inhospitable conditions of urban areas, or on abandoned and poorly maintained properties, such as in war-torn Afghanistan.[76][77]

Until 26 March 2008, a 60-foot-tall (18 m) member of the species was a prominent "centerpiece" of the sculpture garden at the Noguchi Museum in the Astoria section in the borough of Queens in New York City. The tree had been spared by the sculptor Isamu Noguchi when in 1975 he bought the building which would become the museum and cleaned up its back lot. The tree was the only one he left in the yard, and the staff would eat lunch with Noguchi under it. "[I]n a sense, the sculpture garden was designed around the tree", said a former aide to Noguchi, Bonnie Rychlak, who later became the museum curator. By 2008, the old tree was found to be dying and in danger of crashing into the building, which was about to undergo a major renovation. The museum hired the Detroit Tree of Heaven Woodshop, an artists' collective, to use the wood to create benches, sculptures and other amenities in and around the building. The tree's rings were counted, revealing its age to be 75, and museum officials hoped it would regenerate from a sucker.[78]

Europe

Ingo Vetter, a German artist and professor of fine arts at Umeå University in Sweden, was influenced by the idea of the "ghetto palm" and installed a living Ailanthus tree taken from Detroit for an international art show called Shrinking Cities at the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin in 2004.[76][77]

Explanatory notes

- For a more thorough discussion, see the entry for Ailanthus altissima in the Wikimanual of Gardening at Wikibooks.

References

- "Ailanthus altissima". CABI. 6 November 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "The Plant List".

- The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Miller, James Howard (2003). "Tree-of-Heaven". Nonnative invasive plants of southern forests: a field guide for identification and control. USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 29 November 2011. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-062

- Wickert, K. L.; O'Neal, E. S.; Davis, D. D.; Kasson, M. T. (2017). "Seed Production, Viability, and Reproductive Limits of the Invasive Ailanthus altissima (Tree-of-Heaven) within Invaded Environments". Forests. 8 (7): 226. doi:10.3390/f8070226.

- Collin, Pascal; Dumas, Yann (2009). "Que savons-nous de l'ailante (Ailanthus altissima (Miller) Swingle)?" [What do we know about A. altissima?]. Revue Forestière Française. 61 (2): 117–130. doi:10.4267/2042/28895. Cite: Mais comme le fait remarquer Kowarik (2007), sa reproduction végétative le rend en quelque sorte très longévif, le premier individu introduit aux États-Unis en 1784 étant toujours présent grâce à ses drageons. (But as it is mentioned by Kowarik (2007), vegetative reproduction makes [A. altissima] very long-lived, in a way. The first individual planted in the United States in 1784 is still there thanks to its suckers.)

- Sladonja, Barbara; Sušek, Marta; Guillermic, Julia (October 2015). "Review on invasive tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle) conflicting values: assessment of its ecosystem services and potential biological threat". Environmental Management. 56 (4): 1009–1034. Bibcode:2015EnMan..56.1009S. doi:10.1007/s00267-015-0546-5. PMID 26071766. S2CID 8550327.

- "Tree-of-heaven and the Spotted Lanternfly: Two Invasive Species to Watch". Pennsylvania State University. 28 August 2018.

- "Invasive Species Spotlight: Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) | Brandywine Conservancy and Museum of Art".

- Miller, James H. (1990). "Ailanthus altissima". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Vol. 2. Retrieved 7 February 2002 – via Southern Research Station.

- Hu, Shiu-ying (March 1979). "Ailanthus altissima" (PDF). Arnoldia. 39 (2): 29–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Davies, Rob (17 September 2006). "The toxic Tree of Heaven threatens England's green and pleasant land". The Observer. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- "Tree-of-Heaven Ailanthus altissima". Division of Forestry. Ohio Division of Forestry. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- Felter, Harvey Wickes; John Uri Lloyd (1898). "Ailanthus.—Ailanthus.". King's American Dispensatory (18th ed., 3rd rev. ed.). Henriette's Herbal Homepage. A 2-volume modern facsimileis published by Eclectic Medical Publications.

- Ronse De Craene, Louis P.; Elspeth Haston (August 2006). "The systematic relationships of glucosinolate-producing plants and related families: a cladistic investigation based on morphological and molecular characters". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (4): 453–494. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2006.00580.x.

- Fitter, Alastair; More (2012). Trees. [CollinsGem]. ISBN 978-0-00-718306-7.

- Kaproth, Matthew A.; James B. McGraw (October 2008). "Seed viability and dispersal of the wind-dispersed invasive Ailanthus altissima in aqueous environments". Forest Science. 54 (5): 490–496.

- Planchuelo, Greg; Catalán, Pablo; Delgado, Juan A. (2016). "Gone with the wind and the stream: Dispersal in the invasive species Ailanthus altissima". Acta Oecologica. 73: 31–37. Bibcode:2016AcO....73...31P. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2016.02.006. hdl:10016/30463.

- "Tree of heaven is a hellish invasive species. Could a fungus save the day?". Animals. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- Shah, Behula (Summer 1997). "The Checkered Career of Ailanthus altissima" (PDF). Arnoldia. 57 (3): 21–27. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Swingle, Walter T. (1916). "The early European history and the botanical name of the tree of heaven, Ailanthus altissima". Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 6 (14): 490–498.

- Dictionary of Botanical Epithets. Last accessed 15 April 2008.

- Huang, Chenjiu (1997). "Ailanthus Desf.". In Shukun Chen (ed.). Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae. Vol. 43. Beijing: Science Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-7-03-005367-1.

- Zheng, Hao; wu, Yun; Ding, Jianqing; Binion, Denise; Fu, Weidong; Reardon, Richard (September 2004). "Ailanthus altissima" (PDF). Invasive Plants of Asian Origin Established in the United States and Their Natural Enemies, Volume 1. USDA Forest Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2010. FHTET-2004-05

- Li, Hui-lin (1993). "Simaroubaceae". In Editorial Committee of the Flora of Taiwan (ed.). Flora of Taiwan, Volume 3: Hamamelidaceae-Umbelliferea (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-957-9019-41-5. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2006.

- Pan, F.J. (1998). "Ailanthus altissima var. tanakai". 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Hoshovsky, Marc C. (1988). "Element Stewardship Abstract for Ailanthus altissima" (PDF). Arlington, Virginia: The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Kowarik, Ingo (2003). Biologische Invasionen – Neophyten und Neozoen in Mitteleuropa (in German). Stuttgart: Verlag Eugen Ulmer. ISBN 978-3-8001-3924-8.

- Corbett, Sarah L.; Manchester, Steven R. (2004). "Phytogeography and fossil history of Ailanthus (Simaroubaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 165 (4): 671–690. doi:10.1086/386378. ISSN 1058-5893. S2CID 85383552.

- Little Jr., Elbert L. (1979). Checklist of United States Trees (Native and Naturalized). Agriculture Handbooks 541. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service. p. 375. OCLC 6553978. AH541

- Schmeil, Otto; Fitschen, Jost; Seybold, Siegmund (2006). Flora von Deutschland, 93. Auflage (in German). Wiebelsheim: Quelle & Meyer Verlag. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-494-01413-5.

- Stešević, Danijela; Petrović, Danka (December 2010). "Preliminary list of plant invaders in Montenegro" (PDF). 10th SFSES 17–20 June 2010, Vlasina lake. Biologica Nyssana. 1: 35–42 (p.38). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "PGR Forum Crop Wild Relative Catalogue for Europe and the Mediterranean". PGRforum.org. University of Birmingham. 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- Jani, Vasil (2009). Arkitektura e peisazheve (in Albanian). U.F.O. Press, Tirana. ISBN 978-99956-19-37-4.

- Australian Weeds Committee. "Weed Identification – Tree-of-heaven". Weed Identification & Information. National Weeds Strategy. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "Tree of heaven". Pests & Diseases. Biosecurity New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Shafiq, Muhammad; Nizami, M. I. (1986). "Growth behaviour of different plants under gullied area of Pothwar Plateau". Pakistan Journal of Forestry. 36 (1): 9–15.

- "City urges residents to report invasive Tree of heaven". City of Cape Town. 15 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Merriam, Robert W. (October–December 2003). "The Abundance, Distribution and Edge Associations of Six Non-Indigenous, Harmful Plants across North Carolina". Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 130 (4): 283–291. doi:10.2307/3557546. JSTOR 3557546.

- Stipes, R.J. (1995). "A tree grows in Virginia [abstract]" (PDF). Virginia Journal of Science. 46 (2): 105. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011.

- Munz, Philip Alexander; David D. Keck (1973) [1959–1968]. A California Flora and Supplement. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 993. ISBN 978-0-520-02405-2.

- McClintock, Elizabeth. "Ailanthus altissima". The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California. University of California Press. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Howard, Janet L. (2010). "Ailanthus altissima". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- 'Tree-of-heaven's prolific seed production adds to its invasive potential', 2 August 2017, Penn State News

- 'Tree-of-Heaven', USDA (PDF)

- 'Tree-of-Heaven an Exotic Invasive Plant Fact Sheet', May 15, 2014, Ecological Landscape Alliance

- Grime, J. P. (9 October 1965). "Shade Tolerance in Flowering Plants". Nature. 208 (5006): 161–163. Bibcode:1965Natur.208..161G. doi:10.1038/208161a0. S2CID 43191167.

- Knapp, Liza B.; Canham, Charles D. (October–December 2000). "Invasion of an old-growth forest in New York by Ailanthus altissima: sapling growth and recruitment in canopy gaps". Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 127 (4): 307–315. doi:10.2307/3088649. JSTOR 3088649.

- Little, Elbert L. (1980). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Eastern Region. New York: Knopf. p. 540. ISBN 0-394-50760-6.

- Heisy, Rod M. (February 1996). "Identification of an allelopathic compound from Ailanthus altissima (Simaroubaceae) and characterization of its herbicidal activity". American Journal of Botany. 83 (2): 192–200. doi:10.2307/2445938. JSTOR 2445938.

- Heisy, Rod M. (May 1990). "Allelopathic and Herbicidal Effects of Extracts from Tree of Heaven". American Journal of Botany. 77 (5): 662–670. doi:10.2307/2444812. JSTOR 2444812.

- Mergen, Francois (September 1959). "A toxic principle in the leaves of Ailanthus". Botanical Gazette. 121 (1): 32–36. doi:10.1086/336038. JSTOR 2473114. S2CID 84989561.

- Lawrence, Jeffrey G.; Alison Colwell; Owen Sexton (July 1991). "The ecological impact of allelopathy in Ailanthus altissima (Simaroubaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 78 (7): 948–958. doi:10.2307/2445173. JSTOR 2445173.

- Barnes, Jeffrey K. (2 June 2005). "Ailanthus webworm moth". University of Arkansas Arthropod Museum Notes. University of Arkansas. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "EPPO PRA". EPPO PRA. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- Western Farm Press (10 November 2014). "Spotted lanternfly – a new threat to grapes, stone fruit?". Western Farm Press. Penton Agriculture Market.

- Native and Indigenous Biocontrols for Ailanthus altissima (Thesis). 11 July 2008.

- Brooks, Rachel K.; Wickert, Kristen L.; Baudoin, Anton; Kasson, Matt T.; Salom, Scott (1 September 2020). "Field-inoculated Ailanthus altissima stands reveal the biological control potential of Verticillium nonalfalfae in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States". Biological Control. 148: 104–298. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104298. ISSN 1049-9644.

- Snyder, A. L.; Salom, S. M.; Kok, L. T.; Griffin, G. J.; Davis, D. D. (9 August 2012). "Assessing Eucryptorrhynchus brandti (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) as a potential carrier for Verticillium nonalfalfae (Phyllachorales) from infected Ailanthus altissima". Biocontrol Science and Technology. 22 (9): 1005–1019. doi:10.1080/09583157.2012.707639. S2CID 85601294. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- Swearingen, Jil M.; Phillip D. Pannill (2009). "Fact Sheet: Tree-of-heaven" (PDF). Plant Conservation Alliance's Alien Plant Working Group. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). "Simaroubàceae—Ailanthus family". Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 36–40. ISBN 978-0-87338-838-2.

- Duke, James A. (1983). "Ailanthus altissima". Handbook of Energy Crops. Purdue University Center for New Crops & Plant Products. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Barclay, Eliza (24 May 2013). "The Great Charcoal Debate: Briquettes Or Lumps?". NPR. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- Gill, Barbara (2004). "Ailanthus". WoodSampler. Woodworker's Website Association. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Dirr, Michael A. (1998) [1975]. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants (revised ed.). Champaign, Illinois: Stipes. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-87563-795-2.

- Mitchell, Alan (1974). Trees of Britain & Northern Europe. London: Harper Collins. pp. 310–311. ISBN 978-0-00-219213-2.

- Dirr, Michael A.; Zhang, Donglin (2004). Potential New Ornamental Plants from China (PDF). 49th Annual Southern Nursery Association Research Conference. pp. 607–609. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Kuhns, Mike; Larry Rupp (July 2001). "Selecting and Planting Landscape Trees" (PDF). Utah State University Cooperative Extension. p. 19. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Burrows, George Edward; Ronald J. Tyrl (2001). Toxic Plants of North America. Ames: Iowa State University Press. p. 1242. ISBN 978-0-8138-2266-2.

- Hu, Shiu-ying (March 1979). "Ailanthus altissima" (PDF). Arnoldia. 39 (2): 29–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- "Penn State Scientists: Tree of Heaven Really Isn't" (Press release). Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences. 14 June 1999. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Faulkner, William (1932). Sanctuary. Modern Library of the World's Best Books. New York: The Modern Library (Random House). pp. 135–6. OCLC 557539727.

- Faulkner, William (1932). Sanctuary. Modern Library of the World's Best Books. New York: Modern Library (Random House). p. 148. OCLC 557539727.

- Young, Gordon (2013). Teardown: Memoir of a Vanishing City. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0520270527.

- Fergus, Charles (2005). Trees of New England: a Natural History. Guildford: Falcon. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-7627-3795-6.

- Collins, Lisa M. (10 December 2003). "Ghetto Palm". Metro Times Detroit. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Wasacz, Walter (30 January 2007). "Big Ideas for Shrinking Cities". Model D. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Collins, Glen (27 March 2008). "A Tree That Survived a Sculptor's Chisel Is Chopped Down". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

External links

- U.S. Forest Service Fire Effects Information System: Ailanthus altissima

- National Invasive Species Information Center: species profile of Ailanthus altissima (Tree of Heaven), United States National Agricultural Library

- National Park Service, Plant Conservation Alliance, Alien Plant Working Group: Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) report

- Calflora Database: Ailanthus altissima (Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus)—introduced invasive species.

- Cal-IPC/California Invasive Plant Council: plant profile of Ailanthus altissima

- Ailanthus altissima in the CalPhotos photo database, University of California, Berkeley