2023 Atlantic hurricane season

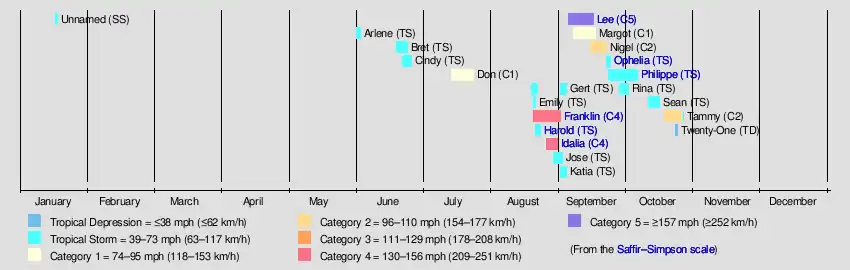

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season is the current hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean in the Northern Hemisphere. It officially began on June 1, and will end on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in the Atlantic.[1] However, the formation of subtropical or tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of a subtropical storm on January 16, the earliest start of an Atlantic hurricane season since Hurricane Alex in 2016.[2] This system went unnamed operationally, as the National Hurricane Center (NHC) treated it as non-tropical. Despite the presence of an intensifying El Niño, which typically results in less Atlantic hurricane activity, the season has been very active in terms of the number of named storms, due in large part to persistent, very warm sea surface temperatures.[3]

| 2023 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | January 16, 2023 |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Lee |

| • Maximum winds | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 926 mbar (hPa; 27.35 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 21 |

| Total storms | 20 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 15 total |

| Total damage | > $2.59 billion (2023 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Several tropical cyclones have impacted land this year, though few have left severe damage. In June, tropical storms Bret and Cindy developed east of the Caribbean Sea (the first occurrence for any June on record), with the former passing through the Lesser Antilles. Tropical Storm Harold struck southern Texas on August 22, and Hurricane Franklin made landfall in the Dominican Republic as a tropical storm the following day, with the latter reaching peak intensity as a high-end Category 4 and bringing tropical-storm-force winds to Bermuda. After briefly attaining Category 4 strength on August 30, Hurricane Idalia made landfall in Florida as a high-end Category 3 hurricane. In early September, Hurricane Lee rapidly intensified into a Category 5 hurricane, then later made multiple landfalls in Atlantic Canada as a strong extratropical cyclone. Later that month, Tropical Storm Ophelia made landfall in North Carolina. In October, Tropical Storm Philippe, the longest-lived tropical cyclone of the year,[4] and Hurricane Tammy both made landfall on Barbuda.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1991–2020) | 14.4 | 7.2 | 3.2 | [5] | |

| Record high activity | 30 | 15 | 7† | [6] | |

| Record low activity | 1 | 0† | 0† | [6] | |

| TSR | December 6, 2022 | 13 | 6 | 3 | [7] |

| TSR | April 6, 2023 | 12 | 6 | 2 | [8] |

| UA | April 7, 2023 | 19 | 9 | 5 | [9] |

| CSU | April 13, 2023 | 13 | 6 | 2 | [10] |

| TWC | April 13, 2023 | 15 | 7 | 3 | [11] |

| NCSU | April 13, 2023 | 11–15 | 6–8 | 2–3 | [12] |

| MU | April 27, 2023 | 15 | 7 | 3 | [13] |

| UPenn | May 1, 2023 | 12–20 | N/A | N/A | [14] |

| SMN | May 4, 2023 | 10–16 | 3–7 | 2–4 | [15] |

| NOAA | May 25, 2023 | 12–17 | 5–9 | 1–4 | [16] |

| UKMO* | May 26, 2023 | 20 | 11 | 5 | [17] |

| TSR | May 31, 2023 | 13 | 6 | 2 | [18] |

| CSU | June 1, 2023 | 15 | 7 | 3 | [19] |

| UA | June 16, 2023 | 25 | 12 | 6 | [20] |

| TWC | June 17, 2023 | 17 | 9 | 4 | [21] |

| CSU | July 6, 2023 | 18 | 9 | 4 | [22] |

| TSR | July 7, 2023 | 17 | 8 | 3 | [23] |

| TWC | July 19, 2023 | 20 | 10 | 5 | [24] |

| UKMO | August 1, 2023 | 19 | 9 | 6 | [25] |

| CSU | August 3, 2023 | 18 | 9 | 4 | [26] |

| TSR | August 8, 2023 | 18 | 8 | 3 | [27] |

| NOAA | August 10, 2023 | 14–21 | 6–11 | 2–5 | [28] |

| Actual activity | 20 | 7 | 3 | ||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

In advance of, and during, each hurricane season, several forecasts of hurricane activity are issued by national meteorological services, scientific agencies, and research groups. More than 25 forecasts were made for the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season.[29] Among them were forecasts from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)'s Climate Prediction Center, Mexico's Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN), Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), the United Kingdom's Met Office (UKMO), and Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. According to NOAA and CSU, the average Atlantic hurricane season between 1991 and 2020 contained roughly 14 tropical storms, seven hurricanes, three major hurricanes, and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 74–126 units.[30] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h). NOAA typically categorizes a season as above-average, average, or below-average based on the cumulative ACE index, but the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a hurricane season is sometimes also considered.[5]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 6, 2022, TSR released the first early prediction for the 2023 Atlantic season, predicting a slightly below average year with 13 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[7] Their updated prediction on April 6, 2023, called for a similar number of hurricanes, but reduced the number of named storms and major hurricanes by one.[8] The following day, the University of Arizona (UA) posted their forecast calling for a very active season featuring 19 named storms, 9 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 163 units.[9] On April 13, CSU researchers released their prediction calling for 13 named storms, 6 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 100 units.[31] Also on April 13, TWC posted their forecast for 2023, calling for a near average season with 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[11] On April 27, University of Missouri (MU) issued their predictions of 10 named storms, 4 between categories one and two, and 3 major hurricanes.[13] On May 1, University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) released their forecast for 12 to 20 named storms.[14] On May 4, SMN issued its forecast for the Atlantic basin, anticipating 10 to 16 named storms overall, with 3 to 7 hurricanes, and 2 to 4 major hurricanes.[15] On May 25, NOAA announced its forecast, calling for 12 to 17 named storms, 5 to 9 hurricanes, and 1 to 4 major hurricanes, with a 40% chance of a near-normal season and 30% each for an above-average season and a below-average season.[16] One day later, UKMO issued its forecast calling for an extremely active season, with 20 named storms, 11 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 222 units.[17]

In general, there was a wide range of conclusions among the groups making pre-season forecasts. With regard to number of hurricanes, projections ranged from 5 by SMN to 11 by UKMO. This reflected an uncertainty on the part of the various organizations about how the expected late-summer El Niño event and near record-warm sea surface temperatures would together impact tropical activity.[29]

Mid-season forecasts

On June 1, the first official day of the season, CSU issued an updated forecast in which they raised their numbers slightly, now expecting a near-average season with 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 125 units. They observed sea surface temperatures in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic had increased further to almost record-highs, which could offset increased wind shear from the impending El Niño.[19] On June 16, UA updated its seasonal prediction, which indicates a very active hurricane season, with 25 named storms, 12 hurricanes, 6 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 260 units.[20] On July 6, CSU issued an updated forecast increasing their numbers, predicting a very active season; they now expect 18 storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes, with an ACE index of 160 units.[22] The following day, TSR released the first seasonal prediction, predicting a slightly above average year with 17 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes and an ACE index of 125.[23] On July 19, TWC updated their forecast, calling for a very active season with 20 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes, citing that a very warm Atlantic ocean could exert more influence and override the El Niño influence.[24]

Seasonal summary

Early activity

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1 and will end on November 30. Nonetheless, it unexpectedly commenced on January 16, when an unnamed subtropical storm formed off the northeastern U.S. coast then moved over Atlantic Canada.[32] Operationally, the NHC considered the storm to be non-tropical, with minimal likelihood of transitioning into a subtropical or tropical cyclone.[33] A post-storm evaluation of the system to determine its proper classification was conducted by a team of forecasters from the NHC and Ocean Prediction Center (OPC). As a result, it was re-designated as subtropical prior to the official start of the season.[32] Tropical Storm Arlene began as a tropical depression on June 1, in the Gulf of Mexico, and became the season's first named storm on June 2. Later that month, when Tropical Storm Bret and Tropical Storm Cindy formed, there were two Atlantic tropical cyclones active simultaneously in June for the first time since 1968.[34] The two developed in the Main Development Region (MDR) from successive tropical waves coming off the coast of West Africa.[35] Their formation also marked the first time on record that two tropical storms have formed in the MDR during the month of June.[36] Next, Subtropical Storm Don formed over the central Atlantic on July 14. A long-lived storm, it later became fully tropical and strengthened into the season's first hurricane as it meandered around the ocean far from land.[37][38]

Peak activity

After a lull in activity, tropical cyclogenesis picked up drastically in late August. Within a span of 39 hours during August 20–22, four tropical storms formed: Emily, Franklin, Gert, and Harold.[39][40] This marked the fastest time four storms were named within the Atlantic basin, surpassing the previous mark of 48 hours, set in 1893 and matched in 1980.[41] Franklin moved across the Dominican Republic, before intensifying into a Category 4 hurricane in the western Atlantic.[42] Gert became a remnant low on August 22, but regenerated into a tropical cyclone ten days later, on September 1.[43] Those four were followed by two more systems during last week of the month: Idalia, and Jose. Idalia formed on August 26 in the Northwestern Caribbean, intensified into a Category 4 hurricane, then made landfall in the Big Bend region of Florida at Category 3 strength. Tropical Storm Jose formed in the open Atlantic on August 31.[44]

The quick pace of storm formation continued into September, the climatological peak of the hurricane season. On September 1, Tropical Storm Katia formed northwest of Cabo Verde in the far eastern Atlantic.[43] After Gert and Katia dissipated, Tropical Storm Lee formed in the central tropical Atlantic on September 5.[45] It became a hurricane a day later, and then rapidly intensified to Category 5 strength, with its winds increasing by 85 mph (135 km/h) during the 24‑hour period ending at 06:00 UTC on September 8. This made Lee the third‑fastest intensifying Atlantic hurricane on record, behind only Felix and Wilma.[46] Lee later made multiple landfalls in Atlantic Canada as an extratropical cyclone. Tropical Storm Margot formed next, and strengthened into the season's fifth hurricane on September 11.[47] They were joined by Tropical Depression Fifteen, later Hurricane Nigel, which formed midway between the Lesser Antilles and Cabo Verde Islands on September 15.[48] Nigel remained far from any land masses, and became extratropical on September 22. That same day, Tropical Storm Ophelia formed offshore of North Carolina.[49] The storm moved inland the following morning at near-hurricane strength.[50] Also on September 23, Tropical Storm Philippe formed in the eastern tropical Atlantic.[51] Right behind Philippe came Tropical Storm Rina five days later. At that time, Philippe and Rina were approximately 620 mi (1,000 km) apart, which is close enough to influence each other's movement and development.[52]

Late activity

After a brief lull in activity, Tropical Storm Sean formed on October 11, in the eastern tropical Atlantic.[53] Later, on October 18, Hurricane Tammy formed.[54] It made landfall on Barbuda, the second system in three weeks to do so, in addition to Philippe.[55] A few days later, short-lived Tropical Depression Twenty-One formed offshore Nicaragua, moved inland, and soon dissipated.[56]

This season's ACE index as of October 26, as calculated by Colorado State University using data from the NHC, is approximately 143.9 units.[57] This number represents sum of the squares of the maximum sustained wind speed (knots) for all named storms while they are at least tropical storm intensity, divided by 10,000. Therefore, tropical depressions are not included.[5]

Systems

Unnamed subtropical storm

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 16 – January 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 976 mbar (hPa) |

On January 16, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) issued a special tropical weather outlook concerning a low-pressure area centered roughly 300 mi (480 km) north of Bermuda. The NHC noted that the low exhibited thunderstorm activity near its center but assessed it as unlikely to transition into a tropical or subtropical cyclone.[58] These thunderstorms may have developed due to the combination of the cyclone's position over the Gulf Stream, where sea surface temperatures around 68–70 °F (20–21 °C) and cold air aloft resulted in high atmospheric instability.[33] Contrary to expectations, a subtropical storm formed on January 16, about 345 mi (555 km) southeast of Nantucket, Massachusetts. Developing with sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), the system initially intensified, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) early on January 17. At 12:45 UTC, it made landfall at Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, as a weakening storm, then soon became a post-tropical low, before dissipating over far eastern Quebec the next day.[32]

There was no storm-related damage reported, likely because its most intense winds remained offshore.[2] The subtropical storm was located within a broader storm system that brought snowfall to parts of coastal New England, including up to 4.5 in (11 cm) in portions of Massachusetts, with 3.5 in (8.9 cm) of snow in Boston.[59] In Nova Scotia, the storm brought wind gusts of near 68 mph (110 km/h) to Sable Island.[32]

Tropical Storm Arlene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 1 – June 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

On May 30, the NHC began monitoring an area of disturbed weather over the eastern Gulf of Mexico for possible tropical development.[60] An area of low pressure developed the following day.[61] The system organized into Tropical Depression Two at 12:00 UTC on June 1, while located off the west coast of Florida.[62] Hurricane hunters investigated the depression on the morning of June 2, and determined that it had strengthened into Tropical Storm Arlene.[63] Moving southward, Arlene remained a minimal tropical storm throughout the day with sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). At 06:00 UTC on June 3, it weakened to a tropical depression. Six hours later, it degenerated into a remnant low, and then subsequently dissipated north of Cuba.[62] Arlene brought 2–6 in (51–152 mm) of rainfall across South Florida, helping to reduce drought concerns along with other rains that week.[64]

Tropical Storm Bret

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 19 – June 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

On June 15, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave about to move off the coast of West Africa.[65] The disturbance became better organized due to warm sea surface temperatures and favorable atmospheric conditions.[66][67] On the morning of June 19, the system organized into Tropical Depression Three,[68] and strengthened into Tropical Storm Bret later that day, about 1,295 mi (2,085 km) east of the southern Windward Islands.[69][70] Gradual intensification occurred during the next couple of days as it headed west towards the Lesser Antilles. Hurricane hunters investigated Bret early on June 22 and found sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a central pressure of 996 mbar (29.4 inHg).[71] Soon after, Bret moved into an area of increased vertical wind shear, causing it to gradually weaken as it moved across the Lesser Antilles.[72] Overnight on June 22–23, it passed just north of Barbados and directly over St. Vincent.[73] Next, during the early hours of June 24, Bret passed just to the north of Aruba as a weakening storm with only minimal convection occurring near its center,[74] and opened into a trough later that day, near the Guajira Peninsula of Colombia.[75]

Bret brought gusty winds and heavy rains to the Windward Islands.[76] Hewanorra International Airport on Saint Lucia reported a wind gust of 69 mph (111 km/h) at 05:00 UTC on June 23, and officials reported that much of the island's electrical grid had been knocked out by the storm.[73] The storm caused damage to buildings in Barbados,[77] It also damaged or destroyed several homes on Saint Vincent.[73]

Tropical Storm Cindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 22 – June 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On June 18, the NHC began tracking a tropical wave that had recently moved off the coast of West Africa,[78] which became more organized the next day.[79] Though the system initially struggled to become better organized, it was in an environment overall conducive to development,[80][81] and organized into Tropical Depression Four on the morning of June 22, while about 1,395 mi (2,245 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[82][83] Despite marginal atmospheric conditions, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Cindy early the next day. At 12:00 UTC on June 24, Cindy's sustained winds intensified to 60 mph (95 km/h). But later that day and continuing into the next, the storm grew progressively weaker. Then, at 06:00 UTC on June 26, Cindy dissipated about 375 mi (605 km) north-northeast of the Northern Leeward Islands.[82][84]

Hurricane Don

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 14 – July 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 988 mbar (hPa) |

A trough of low pressure formed over the central Atlantic on July 11, east-northeast of Bermuda.[85] Though the system remained embedded within the trough and had not developed a compact wind field, a well-defined center of circulation developed along with persistent deep convection early on July 14, prompting the NHC to classify it as Subtropical Storm Don early that morning.[86] Don's deep convection decreased later that day,[87] and it weakened to a subtropical depression early on July 16.[88] The next day, while beginning an anticyclonic loop over the central Atlantic, steered by a blocking ridge to its north, the system transitioned to a tropical depression.[89] Not long after, Don was upgraded to a tropical storm based on satellite wind data.[90] A few days later, while moving over the Gulf Stream on July 22, the storm quickly strengthened into the season's first hurricane.[91] Don remained a minimal Category 1 hurricane for several hours before weakening to a tropical storm early on July 23, when its structure quickly deteriorated as it moved over increasingly cooler waters north of the Gulf Stream.[92] Don continued to weaken due to cold waters and shear into the next day, transitioning to a post-tropical cyclone on July 24.[93]

Tropical Storm Gert

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 19 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

On August 13, the National Hurricane Center began monitoring a tropical wave coming off the coast of Africa, initially giving it a low chance of development through the next seven days.[94] The system struggled to organize amid conditions only marginally favorable, as it moved west-northwest over the open ocean. Eventually, it became sufficiently organized for the NHC to designate it Tropical Depression Six late on August 19.[95] The depression remained weak for a few days as it battled high vertical wind shear and otherwise unfavorable conditions before abruptly strengthening into Tropical Storm Gert at 04:00 UTC on August 22.[96] Soon however, increased wind shear from the outflow of nearby Tropical Storm Franklin caused Gert to weaken to a tropical depression that same afternoon. It subsequently lost its deep convection the following day, becoming a remnant low.[97][98] The low eventually opened up into a trough, but the remnants remained identifiable over the next week as the system trekked slowly northward into the central Atlantic.

Early on August 30, NHC began monitoring the remnants of Gert for potential redevelopment.[99] On September 1, the remnant low became well-defined, and the system regenerated into Tropical Depression Gert.[100] Gert continued its rebound, becoming a tropical storm once again later that day. Moving north-northeastward, its winds reached 60 mph (95 km/h) late on September 2, an intensification achieved in spite of strong northeasterly wind shear.[101] This intensity was maintained into the following day. Gert then began deteriorating while being drawn quickly northward and into the rotation around the larger remnant low of Post-Tropical Cyclone Idalia, and dissipated early on September 4, over the north Atlantic.[102]

Tropical Storm Emily

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 20 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

On August 16, a tropical wave being monitored by the NHC emerged off the coast of Africa into the eastern tropical Atlantic.[103] Over the next few days, the system gradually organized under generally favorable conditions. On August 20, satellite wind data indicated that it was producing gale-force winds in its northern side, and the center became well-defined, prompting the NHC to designate the system as Tropical Storm Emily later that day.[104] Shortly after its formation, Emily was already beginning to be affected by high wind shear and a dry environment, leaving its center exposed. Eventually, Emily became devoid of deep convection and became a post-tropical cyclone on August 21.[105] However, the NHC continued to monitor the system for the chance of it redeveloping.[106] The system showed some signs of reorganization as it moved through the subtropical Atlantic on August 24,[107] but failed to organize further, and started to dissipate later that day.[108] The remnants were then absorbed by an elongated area of low pressure well east-northeast of Bermuda late on August 25.[109]

Hurricane Franklin

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 20 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 926 mbar (hPa) |

On August 17, the NHC first noted the possibility that a low pressure area could soon form at the back end of a trough of low pressure as it headed westward towards the Leeward Islands.[110] The low formed on August 19, near the Windward Islands.[111] It soon formed a well-defined center, after which the NHC designated the system as Tropical Storm Franklin on the afternoon of August 20.[112] While moving through the eastern Caribbean over the next couple of days, Franklin struggled to become better organized while battling strong westerly wind shear pushing most of its convection east of its center.[40][113] Early on August 23, the storm began moving northwestward before turning northward, becoming somewhat better organized and to intensify. Franklin then made landfall with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) south of Barahona, Dominican Republic, shortly before 12:00 UTC that day.[114][115]

Weakening occurred after Franklin made landfall, and it emerged into the Atlantic Ocean at 21:00 UTC as a minimal tropical storm.[116] After struggling with strong westerly shear and land interaction for several days, Franklin entered a more favorable environment for development on August 25 and promptly intensified into a Category 1 hurricane the next morning.[117] A further decrease in wind shear along with less dry air allowed Franklin to begin to rapidly intensify, becoming the season's first major hurricane at 09:00 UTC on August 28.[118] Franklin then began to intensify even more rapidly, quickly becoming a Category 4 hurricane a few hours later,[119] and then reaching its peak maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). After that, Franklin underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, causing it to begin to slowly weaken. That trend continued after the cycle was completed as wind shear from the outflow of Hurricane Idalia increased over Franklin and by 09:00 UTC on August 30, it had weakened to Category 2 strength.[120] Later that day, Franklin turned east-northeastward and passed north of Bermuda. While doing so, the storm's eye structure began to deteriorate due to strong northerly wind shear.[121] Then, on September 1, Franklin transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about 790 mi (1,270 km) northeast of Bermuda, with Category 1-equivalent winds of 85 mph (140 km/h).[122] By September 4, ex‑Franklin was located north of the Azores. That afternoon, the NHC began to monitor the system once again, as it was expected to soon move southeastward towards warmer waters.[123] Some reorganization did take place,[124] but the system did not redevelop into a tropical cyclone. The NHC stopped monitoring the post-tropical cyclone on September 7.[125]

Franklin brought heavy rainfall and wind, causing damage to buildings, homes, and light posts.[126] Two fatalities were reported in the Dominican Republic, with an additional person also missing.[126] At least 350 people were displaced, and more than 500 homes and 2,500 roads were affected or damaged.[127] Several communities in the Dominican Republic were cut off, and nearly 350,000 homes were left without power, and an additional 1.6 million homes were cut off from potable water.[127]

Tropical Storm Harold

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

On August 15, the NHC began to monitor the Gulf of Mexico,[128] in anticipation that a tropical wave moving into the eastern Caribbean would enter the Gulf within a few days, and there interact with the remnants of an old cold front, initiating tropical cyclogenesis.[129] After passing to the south of the Bahamas and between Cuba and Florida,[130] the disturbance reached the Gulf of Mexico and began to become better organized on August 20–21, amid near record-warm sea surface temperatures of 86–90 °F (30–32 °C).[131] Due to the threat the developing system posed to the South Texas Gulf Coast, the NHC initiated advisories on it at 15:00 UTC. on August 21, designating it Potential Tropical Cyclone Nine.[132] The system developed into Tropical Depression Nine about six hours later.[133] Moving quickly westward, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Harold at 06:00 UTC on August 22.[134] Harold strengthened some more before making landfall on Padre Island, in the Texas Coastal Bend region, at around 15:00 UTC that day with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h).[135][136] Six hours later, it weakened into a tropical depression.[137] Early on August 23, it degenerated to a remnant low as its circulation became increasingly ill-defined.[138]

Harold generated modest storm surge as it approached landfall. The highest surge, 2.2 ft (0.67 m), occurred at San Luis Pass.[139] The storm brought 2–4 in (51–102 mm) of rain to coastal southern Texas.[136] Corpus Christi received 5.25 in (133 mm) of rain from the system, including a daily record 4.74 in (120 mm) on August 22.[136] Tropical storm-force winds also spread across the region. Wind gusts reached up to 65 mph (105 km/h) at Corpus Christi and 67 mph (108 km/h) at Loyola Beach.[140] Over 35,000 customers across southern Texas lost power.[141] The London Independent School District was shut down for several days due to damage sustained during the storm.[142] Harold also brought heavy rain and strong wind to parts of northern Mexico, but caused only minor damage as it moved through.[143] In Piedras Negras, 4 inches (100 mm) of rain fell within a few hours.[144]

Hurricane Idalia

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 940 mbar (hPa) |

On August 24, a trough of low pressure formed in the Eastern Pacific basin offshore of the Central America coast.[145] The disturbance crossed over into the Atlantic basin and began to organize as it moved northward through the western Caribbean Sea. The pace of organization quickened on August 26, while the disturbance was located near the northeastern Yucatán Peninsula, and that afternoon was upgraded to Tropical Depression Ten.[146] Later that day, and into the next, the depression drifted due to weak surrounding steering currents, with its center moving in a small counter-clockwise loop.[147][148] The depression became Tropical Storm Idalia at 15:15 UTC on August 27, after a NOAA Hurricane Hunters flight reported that the storm's winds had increased to 40 mph (65 km/h).[149] Early the next morning, Idalia began moving northward[150] toward the Yucatán Channel west of Cuba, intensifying along the way.[151] By early morning on August 29, after passing near the western tip of Cuba, the storm had developed sufficiently to be classified a Category 1 hurricane.[152] Then, benefiting from exceptional environmental conditions,[153] Idalia began to rapidly intensify, reaching Category 2 strength later that day.[154] Rapid intensification continued as the storm accelerated northward through the Gulf of Mexico and Idalia reached Category 4 strength on the morning of August 30, a few hours prior to landfall, reaching its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 940 mbar (27.76 inHg).[155] Idalia's strengthening was then halted by an eyewall replacement cycle, which caused it to weaken slightly before it made landfall at 11:45 UTC, about 20 miles (30 km) south of Perry, Florida, with sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h).[156] Idalia quickly weakened as it moved inland into southeast Georgia,[157] and it was downgraded to a tropical storm at 21:00 UTC that same day.[158] Strong southwesterly wind shear then pushed the storm's convection well north and east of its center as it moved off the northeastern South Carolina coast and emerged into the Atlantic Ocean early on August 31.[159] That afternoon, while southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, Idalia transitioned to a post-tropical cyclone.[160] The storm then moved slowly eastward and impacted Bermuda with tropical-storm-force winds on September 2, as it passed just to the south. Idalia's remnant low then absorbed Tropical Storm Gert,[102] turned northward, and lingered off the coast of Atlantic Canada for several days before dissipating on September 7.[161]

On August 26, 33 Florida counties were placed under a state of emergency (SOE) by Governor Ron DeSantis.[162] Two days later, the governor declared 13 more counties, including some in Northeast Florida, under a SOE.[163] On August 28, hurricane warnings and storm surge warnings were issued for portions of the state's west coast.[151] Idalia caused significant damage across the Big Bend region of Florida and southeastern Georgia. Thousands of structures were damaged or destroyed and four people died in storm-related incidents in the two states. Early estimates placed insured losses at $2.2–5 billion. The hurricane's remnants produced dangerous rip currents across the Eastern United States during Labor Day Weekend, resulting in at least five additional deaths and numerous rescues.[164]

Tropical Storm Jose

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

On August 19, a vigorous tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa.[165] It traversed the Cabo Verde Islands, where an area of low-pressure formed late on August 23.[166] For several days, the disturbance was unable to become better organized.[167] The low at last become better defined on the morning of August 29, after persistent deep convection reignited over the eastern side of the circulation. That afternoon, it developed into Tropical Depression Eleven.[168] The depression meandered due weak steering currents over the next two days, and by August 30, had become less organized due to westerly shear.[169] However, the shear briefly relaxed, and the storm's convective bursting pattern abruptly evolved into curved banding early on August 31, signifying that the depression had strengthened into Tropical Storm Jose.[170] Further development was slow to come as Jose's banding features remained limited, and the convection at its center was shallow.[171] Even so, going into the early morning of September 1, the storm structure improved markedly as convection near the center deepened and a small mid-level eye feature appeared.[172][173] As a result, Jose's maximum sustained winds increased to 60 mph (95 km/h).[174] This intensification was short lived however, and the storm soon began to weaken due to northerly shear from Hurricane Franklin's outflow.[175] Jose then accelerated northward, pulled by the larger and stronger Franklin,[176] and was absorbed into the latter late that day.[177]

Tropical Storm Katia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

On August 28, a tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa.[178] A broad area of low pressure formed two days later near the Cabo Verde Islands.[179] On August 31, the disturbance began exhibiting signs that it was becoming better organized, and the low became better defined by the next morning.[180] As a result, it was designated Tropical Depression Twelve by the NHC at 15:00 UTC on September 1.[181] The following morning, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Katia.[182] On September 2, Katia's internal structure became better defined and its sustained winds reached 60 mph (95 km/h) that evening.[183] Overnight, however, increasing wind shear caused Katia to begin a weakening trend as its surface center became displaced far to the south of a remnant area of convection.[184] By 03:00 UTC on September 4, far northwest of the Cabo Verde Islands, the storm had weakened to a tropical depression.[185] Then, late that day, it degenerated into a remnant low.[186]

Hurricane Lee

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 5 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-min); 926 mbar (hPa) |

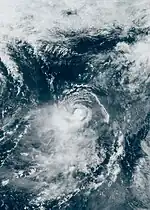

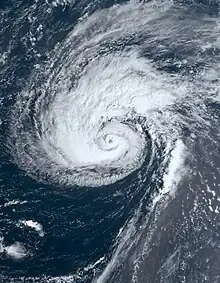

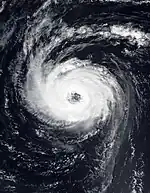

On September 2, a tropical wave emerged into the tropical Atlantic from the west coast of Africa.[187] An area of low pressure formed from the wave two days later to the west-southwest of Cabo Verde.[188] On September 5, the low became more organized, with multiple low-level bands developing and formation of a well-defined center. Consequently, advisories were initiated on Tropical Depression Thirteen at 15:00 UTC that day.[189] Amid favorable conditions for intensification, the depression quickly strengthened into Tropical Storm Lee six hours later.[190] Lee continued to intensify as it became better organized, with convective banding increasing and an eye beginning to form the following afternoon. By 21:00 UTC on September 6, the system strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane[191] while located far to the east of the northern Leeward Islands.[192] Then, during the 24‑hour period ending at 06:00 UTC on September 8, Lee experienced explosive intensification, and reached Category 5 strength, with its winds increasing by 85 mph (135 km/h) to 165 mph (265 km/h).[46]

Several hours later however, an increase of southwesterly wind shear, caused Lee's eye to become cloud filled and the storm became more asymmetric, causing it weaken back to a high-end Category 4 hurricane.[193] The pace of weakening quickened as the day progressed, and by early on September 9, Lee had become a low-end Category 3 hurricane.[194] Later that day, data from an evening hurricane hunters mission into the storm revealed that Lee was undergoing an eyewall replacement cycle and still being adversely affected by modest vertical wind shear; observed peak flight level winds were down from an earlier mission. As a result of these findings, the hurricane was downgraded to Category 2 at 03:00 UTC on September 10.[195] Afterwards, as the eyewall replacement cycle was concluding, the wind shear abated, which permitted the new, larger-diameter eye to contract and to grow more symmetric; as a result, Lee intensified to Category 3 strength once again that same day.[196] The system underwent two more eyewall replacement cycles over the course of the next day and a half, and while they caused some fluctuations in its size and intensity, Lee remained a major hurricane throughout.[47][197]

After tracking west-northwestward to northwestward for much of its trans‑Atlantic journey, Lee turned northward on September 13, moving around the western side of the steering subtropical ridge. That same day, it also weakened to Category 2 strength.[198][199] Then, on the morning of September 14, Lee became a Category 1 hurricane while approaching Bermuda,[200] which it passed to the west by 185 mi (300 km) later in the day.[201] As it pushed northward, continued drier air entrainment and increasingly strong southerly wind shear displaced Lee's convection to the northern side of the system, weakening it further. These factors caused the hurricane to commence its extratropical transition,[202] which was completed by 09:00 UTC on September 16.[203] Later that day, the center of the cyclone made landfall on Long Island, in Nova Scotia.[204] Through the overnight hours into September 17, Lee traversed New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland before moving into the Northern Atlantic.[205]

Swells generated by Lee caused dangerous surf and rip currents along the entire Atlantic coast of the United States. Strong winds with hurricane‑force gusts caused extensive power outages in the U.S. state of Maine, and in the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Three storm-related fatalities have been confirmed: a 15-year-old boy drowned in Fernandina Beach, Florida; a 50-year-old man died in Searsport, Maine, when a tree fell onto the car he was in; and a 21-year-old man who was killed in Manasquan Inlet, New Jersey when the boat he was in capsized and sunk due to a tall wave.[206][207]

Hurricane Margot

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

On September 3, the NHC began to monitor a strong tropical wave moving westward across western Africa.[208] The wave moved into the western Atlantic Ocean two days later, and a broad area of low-pressure with a large area of disorganized showers and thunderstorms quickly formed within it shortly afterwards.[209] Shower and thunderstorm activity within the disturbance become better organized around an increasingly well-defined low-level center on September 7,[210] and Tropical Depression Fourteen formed about 160 mi (255 km) west of Cabo Verde.[211] Later the same day, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Margot.[212] Initially, northerly shear and dry mid-level air intruding from the southwest made it difficult for Margot to become better organized. These hindrances were offset by bursts of deep convection and a diffluent outflow pattern on September 9, allowing for some intensification to occur.[213] Margot continued to intensify gradually over the next couple of days while moving toward the north through the central Atlantic, and a ragged, but partially open eye emerged from the central dense overcast on the morning of September 11.[214] Later that day, Margot's eye became more defined and its overall structure improved, and the storm was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane.[215] It continued along a north to north-northwest track for a few days, exhibiting a double eyewall with a well-defined inner core, reaching maximum sustained winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) on September 13.[216] It then became caught in weak steering currents by a building mid-level ridge to its north and drifted east-southeastward as it began to make a clockwise loop. Margot's slow motion upwelled cooler waters and that coupled with large amounts of dry air caused it to weaken to a tropical storm on September 15.[217] High wind shear and large amounts of dry air continued to negatively affect Margot and weakening continued as the storm's convection began to become increasingly displaced from the system's center.[218] It became bereft of organized deep convection on September 18, and transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone.[219]

Hurricane Nigel

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 15 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 971 mbar (hPa) |

On September 9, the NHC began monitoring an area of low pressure producing a concentrated area of showers and thunderstorms to the southwest of Cabo Verde, as well a tropical wave located inland near the coast of West Africa.[220] After it moved into the tropical Atlantic, a broad area of low pressure formed along the wave on September 11, southeast of the other disturbance.[221] The disturbances began to merge on September 12,[222] and by the next day, the dominant western low was showing some signs of organization.[223] Development continued, and the low became Tropical Depression Fifteen on September 15, far to the east of the Lesser Antilles.[224] Initially, the depression had a very broad structure and its deep convection fluctuated in intensity and organization for about a day without the low-level center becoming better defined.[225] Late on September 16, the depression finally started to become better organized with convective banding developing in its northern semicircle. The depression was then upgraded to Tropical Storm Nigel at 03:00 UTC on September 17.[226] Nigel slowly but steadily became better organized the following day, and then, despite lacking a well-developed inner core, it swiftly strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane on the morning of September 18, as an eyewall began to develop.[227] However, the strengthening trend was momentary halted when dry air entrainment disrupted the storm's inner core.[228]

By early the following morning, the eye of the hurricane was once more becoming better defined and warmer, though convection on the north side was being disrupted by an intrusion of dry air into the inner core.[229] Nonetheless, the system's 50–60 mi-wide (85–95 km) eye was soon fully surrounded by a solid band of deep convection, enabling Nigel to become a Category 2 hurricane late that afternoon.[230] It then turned northward, moving along the western edge of a mid-level ridge over the central subtropical Atlantic.[231] By the end of the day however, deep convection became limited to the southern portion of the band due to a break in the eyewall.[232] Unable to fill in the eyewall breach completely, Nigel weakened to Category 1 strength on September 20.[233] The hurricane's motion later shifted to the north-northeast, then toward the northeast on September 21, and accelerated, within the flow on the southeastern side of a strong mid-latitude trough. At the same time, increasing southwesterly wind shear began causing an elongation of Nigel's cloud pattern toward the northeast, resulting in further weakening.[234] Later, as the system raced northeastward at 37 mph (59 km/h), its environment became more hostile as the wind shear became very strong and sea surface temperatures fell to below 68 °F (20 °C).[235] Consequently, Nigel's winds weakened to below hurricane strength and it transitioned to an extra-tropical cyclone on the morning of September 22, about 640 mi (1,030 km) north-northwest of the Azores.[236]

Tropical Storm Ophelia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 981 mbar (hPa) |

On September 17, the NHC first noted the potential for tropical cyclone development near the southeast coast of the United States in its seven-day outlook.[237] A few days later, a large area of disorganized showers and thunderstorms developed east of Florida within an offshore trough of low pressure.[238] A broad non-tropical area of low pressure formed within the area on September 21. Anticipating that the low could acquire some tropical or subtropical characteristics as it continued to form, coupled with its close proximity to the Southeastern United States, the NHC initiated advisories on it as Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen at 15:00 UTC that day.[239] The system's minimum barometric pressure fell appreciably on the morning of September 22, as it moved generally northward, still attached to a frontal feature. It was generating sustained tropical storm-force winds within its broad, asymmetric wind field, and the deep convection was concentrated to the north of the poorly formed, indistinct low level center of the circulation.[240] Later that day, it became detached from the frontal feature, and was designated Tropical Storm Ophelia.[49] The storm made landfall at 10:15 UTC, near Emerald Isle, North Carolina, about 25 mi (40 km) west-northwest of Cape Lookout, with winds of 70 mph (115 km/h).[241] Inland, Ophelia weakened as it moved northward through the state, and became a tropical depression that evening, after it crossed into southeast Virginia.[242] By 03:00 UTC on September 24, the system had lost its tropical characteristics, becoming a post-tropical cyclone.[243] The next day, its remnant circulation moved eastward off the New Jersey coast, as rains from the system swept northward into New England.[244] The remnants of Ophelia were absorbed by another offshore low-pressure area a few days later.[245]

States of emergency were declared in Virginia, North Carolina, and Maryland ahead of the storm.[246] Five people aboard an anchored catamaran near Cape Lookout, North Carolina, had to be rescued by the U.S. Coast Guard due to deteriorating conditions as the storm approached.[247] Floodwaters inundated communities and roadways along the Atlantic seaboard from North Carolina to New Jersey.[246][247][248] The highest storm surge was 3.67 ft (1.12 m) above mean sea level at Sewell's Point, Virginia.[248] Tropical storm‑force winds from Ophelia downed trees and power lines and caused sporadic property damage along its path.[247][249][250] Wind gusts during the storm reached up to 83 mph (134 km/h) southeast of Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina.[251] Heavy rain also fell along the East Coast, with 7.65 in (194 mm) of rain in Cape Carteret, North Carolina, [248] and 7.47 in (190 mm) in Beach Haven, New Jersey.[251] On September 28–29, the low which had absorbed Ophelia's remnants stalled offshore, causing heavy flash flooding in the New York metropolitan area.[245][252]

Tropical Storm Philippe

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 23 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

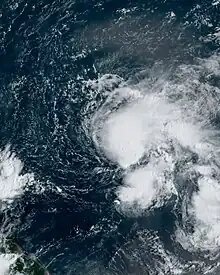

On September 15, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave located inland over West Africa,[253] which moved offshore several days later.[254] On September 20, the wave began interacting with a disturbance just to its west, giving rise to a broad area of low pressure the next day.[255] The disturbance developed a well-defined center on the morning of September 23, west of Cabo Verde, and deep convection associated with it became sufficiently organized to support formation of Tropical Depression Seventeen.[256] Later that day, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Philippe.[51] The storm strengthened some on the morning of September 24, as it moved westward through warm waters, steered along the southern side of a mid-level ridge.[257] Philippe struggled, however, to become better organized overall, due to persistent 25–30 mph (35–45 km/h) deep-layer west-southwesterly wind shear. As a result, its center became fully exposed and far removed to the west of the deep convection the following day.[258] Even so, there was a convective burst that formed near the center of circulation center late on September 26,[259] which continued into the following day. A convective band also began developing on the eastern side of the circulation.[260] Philippe's structure deteriorated somewhat on September 28, with satellite images showing an elongated circulation and multiple centers. As there was some deep convection on the east and southeast sides of what NHC determined was the main center, the system still met the requisite criteria of a tropical cyclone.[261] The storm also stalled, generally drifting to the southwest due to its interaction with Tropical Storm Rina to its east. Philippe remained adrift the following morning, and sheared, with the low-level center pushed to near the western edge of the main area of deep convection.[262] Philippe continued moving erratically for the next few days, strong northwesterly wind shear precluded any significant strengthening from occurring during this time.[263] On October 2, the storm turned toward the northwest, and made landfall on Barbuda that evening,[264] before passing near the U.S. Virgin Islands the next day.[265] Philippe turned northward on October 4, and weakened some due to wind shear, thunderstorm activity became limited to the southeastern quadrant of its circulation and winds of the western side fell to less than tropical storm-force.[266] The storm then transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone two days later as it approached Bermuda.[267][268]

In Guadeloupe, some areas were left without running water, and 2,500 power outages occurred.[269][270] Several homes and vehicles in Antigua and Barbuda were inundated by floodwaters.[270] Multiple schools were also damaged, and rainfall in Vieux-Fort, Guadeloupe, reached 380 mm (15 in).[271][272] Off the U.S. Virgin Islands, 12 people were rescued after a ship started to submerge in rough seas.[273][274] A cold front and Philippe's post-tropical remnants combined to bring up to 6 in (150 mm) to parts of Maine on October 7–8.[275] Gusts in the state were in the 50–60 mph (80–97 km/h) range.[276]

Tropical Storm Rina

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 28 – October 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

On September 23, NHC began to monitor a tropical wave just offshore of West Africa.[277] A broad area of low pressure formed the next day,[278] and the showers and thunderstorms within this disturbance began showing signs of organization a couple days later.[279] Moving west-northwest amid favorable conditions, a well-defined center formed within the disturbance early on September 28, at which time it was designated as Tropical Storm Rina.[280] The next day, Rina's wind field became slightly larger and stronger.[281] But it only intensified for a brief time before weakening once again[282] on account of strong northeasterly wind shear and dry mid-level air.[283] Rina became devoid of organized deep convection early on October 1, and its surface circulation became increasingly ill-defined during the day. Consequently, the system degenerated into a remnant low.[284]

Tropical Storm Sean

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 11 – October 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On October 6, a potent low-latitude tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa.[285] The low became better organized on October 10, and was designated Tropical Depression Nineteen late that day.[286] The next morning, the depression became Tropical Storm Sean about 725 mi (1,165 km) west-southwest of Cabo Verde.[287] Sean remained a highly sheared storm into the next day, with its center located well west of the associated deep convection.[288] Later, after weakening to depression strength overnight,[289] the system restrengthened back into a tropical storm on the morning of October 12.[290] Little additional organization occurred; by the morning of October 14, convective bursts became intermittent and fairly short lived, and the storm weakened once more to a tropical depression.[291] Thereafter, Sean degraded slowly, lingering for a day and a half before becoming a remnant low by very late on October 15.[292]

Hurricane Tammy

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 18 – Present |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

On October 11, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave located just offshore of west Africa.[293] Showers and thunderstorms associated with the disturbance became more concentrated and better organized on October 14,[294] but nearby dry air infiltrated the system, suppressing convection to some degree.[295] Later, when environmental conditions became more conducive, thunderstorm activity within the disturbance was able to become more organized on October 17.[296] The following afternoon, satellite imagery indicated a well-defined low-level surface circulation, prompting the NHC to designate the system as Tropical Storm Tammy.[54] Despite having a sheared appearance due to light to moderate westerly vertical wind shear, hurricane hunter data indicated that Tammy was strengthening as it moved quickly westward through record-warm waters towards the Leeward Islands on October 19.[297][298] The storm's inner core became better organized the following morning. Radar imagery showed that strong convection had quickly evolved into a curved band, and a closed eye. Meanwhile, aircraft data showed that its central pressure had fallen quickly, and sustained winds increased. As a result, the storm was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane.[299] Later, Tammy passed to the east-southeast of Guadeloupe,[300] and then at 01:15 UTC on October 22, made landfall on Barbuda at its initial peak intensity of 85 mph (137 km/h).[301] It pulled away from the Leeward Islands throughout the day, though heavy rains still impacted the islands.[302] After weakening to a minimal hurricane while struggling against wind shear for a couple of days, Tammy began to strengthen on October 25 due to increasing upper-level divergence associated with a deep-layer trough.[303] Later that day, it intensified into a Category 2 hurricane and reached its peak intensity with sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[304] Shortly after peaking, Tammy then began to interact with a front to its north, which caused the hurricane to begin its transition to an extratropical cyclone. Tammy then merged with the front and transitioned into a strong extratropical cyclone early on October 26.[305] The next day however, Tammy became detatched from the front, and redeveloped into a tropical storm.[306]

Barbuda received minimal damage while Antigua had only minor damage, though blackouts occurred across both islands. Two families on Barbuda had to be evacuated.[55] Rainfall amounts across the Leeward Islands were between 4 to 8 in (100 to 200 mm), and storm surge heights were between 1 to 3 ft (0.30 to 0.91 m).[307]

Tropical Depression Twenty-One

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 23 – October 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On October 20, a broad area of low pressure developed over the far southwestern Caribbean Sea.[308] As the disturbance moved slowly towards the coast of Nicaragua on October 23, its surface circulation became more defined and heavy thunderstorm activity grew more intense and organized, resulting in the formation of Tropical Depression Twenty-One that afternoon.[309] It quickly made landfall in Nicaragua and dissipated the next day.[310]

Storm names

The following list of names is being used for named storms that form in the North Atlantic in 2023. This is the same list used in the 2017 season, with the exceptions of Harold, Idalia, Margot, and Nigel, which replaced Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Nate, respectively.[311] The names Harold, Idalia, Margot, and Nigel have been used for the first time this year. Names retired after the season, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2024. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2029 season.

|

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed in the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, intensities, areas affected, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2023 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unnamed | January 16–17 | Subtropical storm | 70 (110) | 976 | New England, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Arlene | June 1–3 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 998 | Florida, Western Cuba | None | None | |||

| Bret | June 19–24 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 996 | Windward Islands, Leeward Antilles, Northern Venezuela, Northeastern Colombia | Minimal | None | [77] | ||

| Cindy | June 22–26 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Don | July 14–24 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 988 | None | None | None | |||

| Gert | August 19 – September 4 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | None | None | None | |||

| Emily | August 20–21 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1001 | None | None | None | |||

| Franklin | August 20 – September 1 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 926 | Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bermuda | $90 million | 2 | [115][312] | ||

| Harold | August 21–23 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 996 | Texas, Northern Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Idalia | August 26–31 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 940 | Yucatan Peninsula, Cayman Islands, Western Cuba, Southeastern United States, Bermuda | >$2.5 billion | 7 (3) | [313][314][315] [316][317] [318][319] | ||

| Jose | August 29 – September 2 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 996 | None | None | None | |||

| Katia | September 1–4 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 998 | None | None | None | |||

| Lee | September 5–16 | Category 5 hurricane | 165 (270) | 926 | Bermuda, Northeastern United States, Atlantic Canada | Unknown | 3 | [206][320][207] | ||

| Margot | September 7–17 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 970 | None | None | None | |||

| Nigel | September 15–22 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 971 | None | None | None | |||

| Ophelia | September 22–24 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 981 | East Coast of the United States | Unknown | None | |||

| Philippe | September 23 – October 6 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 998 | Leeward Islands, Bermuda, Northeastern United States, The Maritimes, Quebec | Unknown | None | |||

| Rina | September 28 – October 2 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 999 | None | None | None | |||

| Sean | October 11–16 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Tammy | October 18 – Present | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 965 | Leeward Islands | Unknown | None | [55] | ||

| Twenty-One | October 23–24 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1007 | Nicaragua | Unknown | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 21 systems | January 16 – Season ongoing | 165 (270) | 926 | >$2.59 billion | 12 (3) | |||||

See also

- Weather of 2023

- Tropical cyclones in 2023

- 2023 Pacific hurricane season

- 2023 Pacific typhoon season

- 2023 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2022–23, 2023–24

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2022–23, 2023–24

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2022–23, 2023–24

References

- "Hurricanes Frequently Asked Questions". Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. June 1, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- Barker, Aaron (May 11, 2023). "First storm of 2023 hurricane season formed in January, NHC says". Fox Weather. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- Morales, John (October 6, 2023). "John Morales examines the 2023 hurricane season, now that 70% of it is behind us". Miami, Florida: WTVJ. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (October 6, 2023). "Long-lived but underwhelming Philippe goes post-tropical". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- "Background Information: North Atlantic Hurricane Season". College Park, Maryland: Climate Prediction Center. April 9, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Evans, Steve (December 6, 2022). "TSR: 2023 Atlantic hurricane season activity forecast to be 15% below norm". Artemis.bm. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- Lea, Adam; Wood, Nick (April 6, 2023). April Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2023 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- Davis, Kyle; Zeng, Xubin (April 7, 2023). "Forecast of the 2023 Hurricane Activities over the North Atlantic" (PDF). Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- Klotzbach, Phil (April 13, 2023). "CSU researchers predicting slightly below-average 2023 Atlantic hurricane season" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- Erdman, Jonathan (April 13, 2023). "2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook: A Developing El Niño Vs. Warm Atlantic Ocean". Atlanta, Georgia. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- Peake, Tracy (April 13, 2023). "NC State Researchers Predict Normal Hurricane Season". NC State News. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- Gotsch, Chance (April 27, 2023). "University of Missouri submits 2023 Atlantic tropical storm and hurricane forecast". ABC News 17. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- "The 2023 North Atlantic Hurricane Season: University of Pennsylvania Forecast". Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Mann Research Group, University of Pennsylvania. May 1, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- "Temporada de Ciclones Tropicales 2023" [Tropical Cyclone Season 2023] (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. May 4, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- "NOAA predicts a near-normal 2023 Atlantic hurricane season". NOAA. May 25, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- "Tropical storm seasonal forecast for the June to November period issued in May 2023". UK Met Office. May 26, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- Lea, Adam; Wood, Nick (May 31, 2023). Pre-Season Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2023 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- Klotzbach, Philip J.; Bell, Michael M.; DesRosiers, Alexander J. (June 1, 2023). Extended-range forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and landfall strike probability for 2023 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- Davis, Kyle; Zeng, Xubin (June 16, 2023). "Forecast of the 2023 Hurricane Activities over the North Atlantic" (PDF). Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Erdman, Jonathan (June 17, 2023). "Above-Average Activity Expected In Latest TWC 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook". The Weather Company. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- Klotzbach, Philip J.; Bell, Michael M.; DesRosiers, Alexander J. (July 6, 2023). Forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and landfall strike probability for 2023 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- Lea, Adam; Wood, Nick (July 7, 2023). July Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2023 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Erdman, Jonathan (July 19, 2023). "Above-Average Activity Expected In Latest TWC 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook". The Weather Company. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- "Tropical storm seasonal forecast update August 2023". UK Met Office. August 1, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (August 3, 2023). "'Clash of the titans': Hurricane forecasters lay odds on an epic battle". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- Lea, Adam; Wood, Nick (August 8, 2023). August Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2023 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- "NOAA forecasters increase Atlantic hurricane season prediction to 'above normal'". NOAA. August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff (June 1, 2023). "Hurricane season begins with a Gulf of Mexico tropical disturbance to watch". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- Saunders, Marc; Lea, Adam (December 9, 2020). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2021" (PDF). tropicalstormrisk.com. London, UK: University College London. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- Klotzbach, Philip; Bell, Michael; DesRosiers, Alexander (April 13, 2023). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity And Landfall Strike Probability For 2023" (PDF). CSU Tropical Weather & Climate Research. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- Papin, Philippe; Cangialosi, John; Beven, John (July 6, 2023). Tropical Cyclone Report: Unnamed Subtropical Storm (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- Erdman, Jonathan (January 17, 2023). "Did A January Subtropical Storm Form Off The East Coast". Weather Underground. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- "Tropical Storms Bret And Cindy Become First June Pair To Form East Of Lesser Antilles In Same Hurricane Season". The Weather Channel. June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (June 19, 2023). "TD 3: a rare June hurricane threat for the Caribbean". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (June 23, 2023). "Unusual June Tropical Storms Bret and Cindy stir up the Atlantic". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- Murphy, John (July 22, 2023). "Don strengthens into 1st hurricane of 2023 Atlantic season". accuweather.com. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (July 24, 2023). "Powerful Typhoon Doksuri threatens the Philippines and Taiwan". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- "NOAA Satellites Monitor Increased Storm Activity in the Atlantic and Pacific". Silver Spring, Maryland: National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. August 24, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (August 22, 2023). "Harold hits South Texas, Franklin heads for Hispaniola". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (August 22, 2023). "Harold hits South Texas, Franklin heads for Hispaniola". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- Jones, Judson; Pérez, Hogla Enecia (August 30, 2023). "Hurricane Franklin Causing 'Significant' Rip Currents Along East Coast". The New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 1, 2023). "Category 4 Typhoon Saola batters Hong Kong". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (August 31, 2023). "Idalia heads out to sea after flooding coastal South Carolina". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 5, 2023). "Tropical Depression 13 poised to become a powerful hurricane". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 8, 2023). "Hurricane Lee peaks as a Cat 5 with 165-mph winds". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 12, 2023). "Hurricane Lee grows in size, maintaining its intensity". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- Henson, Bob; Masters, Jeff (September 16, 2023). "Lee goes post-tropical before reaching Nova Scotia". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (September 22, 2023). "Tropical Storm Ophelia to rake the U.S. East Coast this weekend". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- Witte, Brian (September 23, 2023). "Tropical Storm Ophelia moves inland after making landfall in North Carolina with heavy rain". PBS NewsHour. Associated Press. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- Belles, Jonathan (September 23, 2023). "Tropical Storm Philippe forms Midway Between Africa And The Caribbean". The Weather Channel. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 28, 2023). "Tropical storms Philippe and Rina jostle for position in the Atlantic". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- Donegan, Brian; Wulfeck, Andrew (October 11, 2023). "Tropical Storm Sean forms in eastern Atlantic as Invest 94L off Africa already shows signs of organization". FOX Weather. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- Berg, Robbie (October 18, 2023). Tropical Storm Tammy Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- Martinez, Ignacio; Llano, Fernando (October 22, 2023). "Pacific and Atlantic hurricanes Norma and Tammy make landfall on Saturday in Mexico and Barbuda". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (October 24, 2023). "Otis gains strength as it approaches the southern Mexican coast". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- "Real-Time Tropical Cyclone North Atlantic Ocean Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- Cangialosi, John (January 16, 2022). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Shapiro, Emily; Wnek, Samantha (January 17, 2023). "National Hurricane Center issues rare January tropical weather outlook". ABC News. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- Papin, Philippe; Blake, Eric (May 30, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- Beven, Jack (May 31, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- Reinhart, Brad (July 13, 2023). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Arlene (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- Cangialosi, John; Hogsett, Wallace; Delgado, Sandy (June 2, 2023). Tropical Storm Arlene Special Discussion Number 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- Truchelut, Ryan (June 7, 2023). "What Arlene, northeast Atlantic hotspot tell us about Florida hurricane season". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- Bucci, Lisa (June 15, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- Papin, Philippe (June 17, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- Masters, Jeff (June 15, 2023). "An early start to the Atlantic Cape Verde season?". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connection. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- Blake, Eric; Kelly, Larry (June 19, 2023). Tropical Depression Three Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- Blake, Eric; Kelly, Larry (June 19, 2023). Tropical Storm Bret Advisory Number 2 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- Blake, Eric; Kelly, Larry (June 19, 2023). Tropical Storm Bret Discussion Number 2 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- Berg, Robbie (June 22, 2023). Tropical Storm Bret Discussion Number 12 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- Beven, Jack (June 23, 2023). Tropical Storm Bret Discussion Number 15 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (June 23, 2023). "Unusual June Tropical Storms Bret and Cindy stir up the Atlantic". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- Berg, Robbie (June 24, 2023). Tropical Storm Bret Discussion Number 20 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- Cangialosi, John (June 24, 2023). Remnants of Bret Discussion Number 22 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- "Tropical Storm Bret strikes Caribbean with heavy rain and wind". Reuters. June 23, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- "Tropical Storm Bret leaves some damage". Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- Papin, Philippe (June 18, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- Kelly, Larry; Blake, Eric (June 19, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- Roberts, Dave; Berg, Robbie (June 20, 2023). Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- Henson, Bob (June 21, 2023). "Lesser Antilles prep for Tropical Storm Bret". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connection. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- Cangialosi, John (July 27, 2023). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Cindy (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- Bucci, Lisa (June 22, 2023). Tropical Depression Four Advisory Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- Beven, Jack (June 25, 2023). Remnants Of Cindy Advisory Number 16 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- Cangialosi, John; Kelly, Larry (July 11, 2023). Seven-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- Cangialosi, John (July 14, 2023). Subtropical Storm Don Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- Berg, Robbie (July 14, 2023). Subtropical Storm Don Discussion Number 2 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- Blake, Eric (July 16, 2023). Subtropical Depression Don Discussion Number 10 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- Blake, Eric (July 17, 2023). Tropical Depression Don Discussion Number 14 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- Papin, Philippe (July 18, 2023). Tropical Storm Don Discussion Number 16 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Brown, Daniel (July 22, 2023). Hurricane Don Discussion Number 35 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- Blake, Eric (July 23, 2023). Tropical Storm Don Discussion Number 37 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Kelly, Larry; Pasch, Richard (July 24, 2023). Post-Tropical Cyclone Don Discussion Number 42 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- Papin, Philippe (August 13, 2023). Seven-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- Bucci, Lisa (August 19, 2023). Tropical Depression Six Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- Roberts, Dave (August 21, 2023). Tropical Storm Gert Special Discussion Number 7 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- Zelinsky, David (August 21, 2023). Tropical Depression Gert Advisory Number 10 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2023.