Typhoon Ike

Typhoon Ike, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Nitang, was the second deadliest tropical cyclone in the 20th century in the Philippines. Ike originated from an area of disturbed weather southeast of Guam on August 21, 1984, and five days later, developed into a tropical depression. Following an increase in organization, the depression attained tropical storm intensity on August 27. Initially tracking west-southwest, the storm gradually gained strength as wind shear resulted relaxed and Ike became a typhoon on August 30. Continuing to rapidly intensity, Ike turned west and attained peak intensity on September 1, with the Japan Meteorological Agency estimating winds of 170 km/h (105 mph). At around 14:00 UTC that day, Ike made landfall on the northeastern tip of Mindanao. The cyclone emerged into the South China Sea on September 3 as a tropical storm before re-intensifying into a typhoon and moving onshore Hainan. Ike then struck the Chinese mainland as a tropical storm in Guangxi and dissipated on September 6.

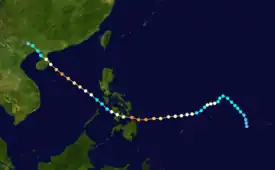

Ike at peak intensity near the Philippines on September 1 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 26, 1984 |

| Dissipated | September 6, 1984 |

| Very strong typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 165 km/h (105 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 950 hPa (mbar); 28.05 inHg |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS) | |

| Highest winds | 230 km/h (145 mph) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 1,474 total |

| Damage | $230 million (1984 USD) |

| Areas affected |

|

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1984 Pacific typhoon season | |

During its formative stages, Ike brushed Guam, although its compact size reduced the extent of damage. Typhoon Ike also struck the Philippines a mere four days after Tropical Storm June inundated the northern portion of the Philippines and also was suffering from the nation's worst economic crisis since independence in 1946. It also left a path of destruction in the Philippines that at the time was unparalleled in its modern history. Most of the deaths were in the province of Surigao del Norte, where around 1,000 died, 330 others were wounded, and 80% of structures along with 27 towns were flattened. Typhoon Ike was considered the worst typhoon to affect the province in 20 years. Roughly 90% of homes in Surigao City were leveled, leaving 90,000 individuals homeless. Throughout Negros Island, over 4,000 dwellings were destroyed, resulting in nearly 75,000 people homeless after a river burst its banks. In the province of Bohol, Ike was the deadliest natural disaster in the province's history, with 198 fatalities in addition to 89,000 homes damaged or destroyed. Overall, 1,426 people were killed as a result of the typhoon in the archipelago. At the time, Ike was the deadliest typhoon to hit the country during the 20th century, surpassing the previous record of Typhoon Amy in 1951. A total of 1,856 people were injured. Furthermore, 142,653 homes were damaged and 108,219 others were destroyed. Nationwide, damage was estimated at $230 million, including $76.5 million from crop damage and $111 million from property damage. Following the storm, Philippines authorities initially distributed $4 million in aid but refused international aid. However, authorities reversed its decision on September 8 due to lack of local resources and started accepting foreign aid. In all, over $7.5 million was donated to the country to provide relief.

Ike was the worst tropical cyclone to strike the Guangxi province in China since 1954, where 14 people were killed. Across the country, around 13,000 structures were damaged or destroyed. Nationwide, 46 people were killed and 12,000 ha (29,651 acres) of sugar cane were destroyed. About 1,315,420 kg (2,900,000 lb) of vegetables were lost. Elsewhere, two people were killed and seven were listed missing in Thailand due to flash flooding.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Typhoon Ike can be traced back to an area of disturbed weather first identified as part of the region's monsoon trough southeast of Guam on August 21. Over the next few days, the disturbance failed to develop as a result of inhibiting wind shear which remained over the area. However, the shear quickly abated on August 25, allowing for convection to build and persist over the system's center of circulation;[1] this prompted the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) to classify the system at 06:00 UTC on August 26 as a tropical depression.[2][nb 1] Later that day, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert for the system, following a rapid increase in the system's organization.[1] Tracking generally northward, it continued to improve in organization and became more compact,[1] allowing both the JMA and the JTWC to upgrade the system to Tropical Storm Ike on August 27.[4][nb 2]

Ike's track northward brought it 165 km (105 mi) southwest of Guam before the tropical storm stalled and turned towards the west-southwest on August 28 as a result of a subtropical ridge to its north. Initially, persistent wind shear limited intensification,[1] but data from the JTWC suggested that Ike briefly attained typhoon status on August 29.[6] By August 30, an upper-level anticyclone became established over the system, resulting in favorable conditions aloft, and Ike entered a second intensification phase.[1] At midday, both the JTWC and JMA estimated that Ike attained typhoon status.[4] On August 31, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) also monitored the storm and assigned it with the local name Nitang.[7] Now assuming a more westerly bearing, Ike continued to rapidly strengthen;[1] at 12:00 UTC on September 1, the typhoon reached its peak intensity with winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) and a barometric pressure of 950 mbar (hPa; 28.05 inHg) as analyzed by the JMA.[2] Meanwhile, the JTWC estimated maximum intensity of 235 km/h (145 mph).[4]

With maximum intensity, Ike made landfall on the northeastern tip of Mindanao at around 14:00 UTC on September 1,[8] taking 30 hours to track across the southern extent of the Philippines. The cyclone emerged into the South China Sea on September 3, but due to land interaction,[1] both the JTWC and JMA reported that Ike had weakened to a tropical storm upon its emergence.[4] The storm tracked northwestward across the South China Sea over the next few days.[1] Ike regained its former typhoon classification on September 3, according to the JTWC,[6] and on September 4, according to the JMA.[2] Several hours later, data from a Hurricane Hunter aircraft indicated that Ike had developed a 55 km (35 mi) wide eye.[1] The JMA estimated that it reached a secondary peak intensity on September 4 with winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) and a pressure of 955 mbar (hPa; 28.20 inHg), only slightly weaker than its peak strength[4] while the JTWC estimated a secondary peak of 185 km/h (115 mph).[6] The combination of increased wind shear induced by a trough passing to the storm's north and the typhoon's proximity to land caused Ike to weaken. The storm made a September 5 landfall on Hainan as a minimal typhoon. The storm continued to weaken after crossing Hainan, with both the JTWC and JMA estimating that it moved into the Chinese mainland as a tropical storm while it was located 110 km (68 mi) southeast of Nanning.[1][4] Thereafter, Ike quickly weakened inland and dissipated on September 6.[1][4]

Preparations

Prior to the typhoon's first landfall, a typhoon warning was issued by the Manila Weather Bureau for the Philippine provinces of Surigao del Norte, Agusan, Leyte, Samar, Camiguin, Bohol, Cebu, Misamis Oriental, and Negros.[9] Local authorities warned at risk residents via radio to flee to higher ground due to the threat of destructive storm surge.[10] Although no mandatory evacuation was in effect, local radio stations broadcast appeals for evacuation every 30 minutes under the direction of the Manila Weather Bureau.[9]

When Ike began to turn towards the northwest on September 3, typhoon warnings were issued for coastal areas between Hong Kong and Beihai. Hundreds of cargo ships left port to escape the typhoon. In Zhanjiang, sandbagging operations took place in an effort to construct a barrier against Ike's storm surge. Hundreds of thousands of residents evacuated from coastal areas.[11] Offshore, four foreign oil companies evacuated workers off of drilling rigs in the South China Sea.[12] Further north, in Hong Kong, a No 1. hurricane signal was issued on September 4 and later that day was upped to a No 3. hurricane signal, but this signal was dropped once the storm dissipated inland.[8]

Impact

Philippines

| Rank | Storm | Season | Fatalities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Haiphong" | 1881 | 20,000 | [13] |

| 2 | Yolanda (Haiyan) | 2013 | 6,300 | [14] |

| 3 | Uring (Thelma) | 1991 | 5,101–8,000 | [15] |

| 4 | Pablo (Bopha) | 2012 | 1,901 | [15] |

| 5 | "Angela" | 1867 | 1,800 | [16] |

| 6 | Winnie | 2004 | 1,593 | [16] |

| 7 | "October 1897" | 1897 | 1,500 | [16][17] |

| 8 | Nitang (Ike) | 1984 | 1,426 | [18] |

| 9 | Reming (Durian) | 2006 | 1,399 | [16][15] |

| 10 | Frank (Fengshen) | 2008 | 1,371 | [nb 3][19][20] |

Upon making landfall on northeastern Mindanao on September 1,[21] Ike became the strongest tropical cyclone to strike the Philippines since Typhoon Joan of the 1970 Pacific typhoon season.[22] Typhoon Ike also struck the country a mere four days after Tropical Storm June inundated the northern portion of the country, which claimed 53 lives.[23] The islands were also suffering from the worst economic crisis since independence in 1946.[24] Power was knocked out to much of the country for four days.[12]

The typhoon left a path of destruction in the Philippines that was at its time unparalleled in modern Philippine history.[1] Most of the fatalities were in the province of Surigao del Norte, where around 1,000 died[1] and 27 towns were flattened.[25] More than half of Surigao del Norte's cattle, goat, and pig population were killed.[8] Waves 2,440 mm (8 ft) slammed into the provincial capital of Surigao City, which resulted in 85 casualties.[26] Around 90% of homes in the city were leveled, leaving 90,000 out the town's 135,000 citizens homeless. Fresh water shortages occurred after power was lost in Surigao City.[27] To the southwest in Mainit, numerous homes were swept away after Lake Mainit overflowed its banks,[28] leading to the deaths of over 200 people.[27] On nearby Nonoc Island, 101 were killed, primarily due to drownings,[26] and all but 20 houses of the 2,000 on the island were demolished.[29] Provincewide, 330 people were wounded[30] and 70% of homes, mostly made of wood,[31] and 80% of buildings were destroyed,[8] which resulted in 480,000 homeless.[32] Typhoon Ike was considered the worst typhoon to affect the province in 20 years.[33] Further south, in the province of Surigao del Sur, 16 people perished.[34]

Ten boats sunk offshore the capital city of Manila, where more than 6,000 residences were destroyed.[35] However, the capital was spared the inner core of the typhoon.[27] Elsewhere, in Cebu, thousands of refugees stayed in town halls and churches during the storm;[36] 10 people were injured by flying debris and another 12 went missing on the island.[37] Strong winds snapped power lines in Cebu, resulting in a power outage that impacted the entire province and halted all radio broadcasts in the prefecture.[38] Off of Cebu City, 10 ferries sunk due to the strong waves generated by Ike. Roads connecting Cebu City to 44 peripheral towns were blocked by fallen trees and severe flooding.[37] Throughout the province, 90,000 people were left homeless[25] and damage totaled at least $6.8 million.[27]

Throughout Negros Island, over 4,000 dwellings were destroyed, displacing nearly 75,000 people.[39][40] The Ilog River, the longest on Negros Island, burst its banks and sent a deluge of mud, water, and debris to the municipalities of Kabankalan and Ilog.[41] Across the province of Negros Occidental, 120 people died,[42] including 50 in Kabankalan[28] and 2 in the nearby community of San Carlos.[42] In Negros Oriental, 60 others died[42] and 29 were initially reported missing.[43] Across Mindanao Island, 305 people were killed. A total of 29 people were killed in the province of Agusan del Norte.[44] Six people died in the province of Misamis Oriental.[28] Five others died in Camiguin.[34]

In the Bohol province, the death toll reached 198, making Ike the deadliest natural disaster in the province's history.[45][46] Province-wide, 938 public schools, poultry and livestock, churches, bridges and other public buildings were destroyed or damaged. Around 89,000 houses were damaged or destroyed,[46] which resulted in 58,000 people homeless.[42] In Mabini, 14 fatalities were reported while Guindulman suffered the worst effects in the province. Both the Inabanga and Loboc Rivers swelled and flooded their respective towns for days forcing church services to be held at their convents due to heavy deposits of mud in the church proper.[46] In other provinces across the region, twenty-four died in Leyte, two other fatalities occurred in Aklan,[33] and three people were killed in Iloilo.[34]

Nationwide, 1,426 people were killed as a result of the typhoon,[8] making Ike the deadliest typhoon to hit the country in the 20th century at the time, surpassing the previous record of Typhoon Amy in 1951.[47] This mark would be eclipsed, however, by Tropical Storm Thelma in 1991.[48] A total of 1,856 people were hurt.[49] Furthermore, 108,219 houses were destroyed while an additional 142,653 homes were damaged. In all, damage was estimated at $230 million. Crop damage was placed at $76.5 million,[50][nb 4] with damage to coconut plantations totaling $61 million.[51] Property damage on the islands reached $111 million.[8]

China

Across Hainan Island, winds of 103 km/h (64 mph) were measured,[8] resulting in power being knocked out for the entire island.[52] At the time of its second landfall, Ike was a large but weakening tropical system, with gale-force winds extending out 315 km (195 mi) from the center. The storm brought 76–127 mm (3.0–5.0 in) of rain to most of the affected areas, with locally higher amounts. Thirteen fishermen were overcome by the 7.6–9.1 m (25–30 ft) swells off the coast of Weizhou Island.[53] Across the Guangdong, 2,000 houses were destroyed.[52] In the Guangxi near the storm made landfall, the storm destroyed zones of homes, factories, and boats,[54] especially in the coastal towns of Beihai, Qinzhou, and Fancheng.[55] In nearby Nanning, half of the city was left without power, one building collapsed, and four hundred fifty trees were uprooted.[8] There, 13 people were killed[56] and two people were severely wounded.[51] Provincewide, 14 people were killed, with six others rendered missing[8] while 12,000 ha (29,651 acres) of sugar cane was destroyed.[51] Ike was considered the worst typhoon to strike the province since 1954.[57]

Nationwide, numerous trees and power lines were downed by the storms' high winds and an estimated 13,000 structures were damaged or destroyed. A total of 46 people were killed by the remnants of Ike in central China.[53] There were also reports of 13 people missing.[58] An estimated 12,000 ha (29,650 acres) of sugar cane were destroyed and about 1,315,425 kg (2,900,000 lb) of vegetables were lost.[59]

A minimum sea level pressure of 1,009 mbar (29.8 inHg) was recorded at the Hong Kong Royal Observatory. A peak wind gust of 89 km/h (55 mph) was reported on the island of Tai O. A peak sustained wind of 54 km/h (34 mph) was recorded on Lei Yue Mun. Tate's Cairn measured 24.2 mm (0.95 in) of rain, the highest total within the vicinity of Hong Kong from September 4 to 6. In the western portion of Hong Kong, one woman was injured by a fallen wooden plank. Nearby, a scaffolding and hoardings were blown down at a construction site. Otherwise, no damage was reported in Hong Kong.[8]

Elsewhere

Due to the proximity of Ike to Guam upon its formation, the island was placed under the "Condition of Readiness" level; this was the first time that such a high readiness level was issued since Typhoon Pamela in 1982. Although Ike passed somewhat near the island, the storm's compact size during its formative stages mitigated any damage. Despite being near typhoon intensity at the time, a station on Nimitz Hill only documented winds of 30 km/h (19 mph), with higher gusts.[1]

The outer rainbands of the typhoon brought unseasonably heavy rains to Thailand.[60] There, four people were reported missing and ten were injured after water from an overflowing dam tipped over a bus.[34] Two people were killed and three were rendered missing due to flash flooding in Bangkok.[52] Elsewhere, the outer extremities of Ike produced light rainfall and light breezes on Okinawa, peaking at 3.8 mm (0.15 in) in Ibaruma,[61] most of which fell in an hour.[62]

Aftermath

Immediately following Ike, the Government of the Philippines dispatched a C-130 aircraft carrying relief supplies to the affected areas,[63] including 32,000 tonnes (35,000 tons) to Suriago City.[27] The large loss of life resulted in morgues running out of coffins, leading to bodies being immediately buried to prevent the spread of disease. Imelda Marcos, the wife of president Ferdinand Marcos, flew to Surigao City to personally hand out relief supplies.[64] Ferdinand Marcos warned on television for profiteers and looters to not "take advantage of the situation".[33] Nevertheless, the typhoon set the stage for protests against Marcos and his handling of the storm throughout the country for the rest of the month.[65]

The president set aside $4 million for relief work but initially refused any international aid.[66] Despite this, the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies appealed in Switzerland for $800,000 in emergency aid for victims of the typhoon.[26] The Philippines Air Force delivered 907,185 kg (2,000,000 lb) of food, medicine, and clothes.[67] According to officials, 92 health teams backed by 17 army medical units were fielded; these teams distributed $1.66 million worth of medicine.[32] The Philippine Red Cross disturbed food to 239,331 people, or 44,247 families.[68] The mayor of Suriago City applied for national aid since the city's residents faced starvation.[47] On September 9, President Marcos ordered $100,000 worth of cash to seven province governors, and released $555,000 with the intent of rebuilding Suriago City.[69] A task force was also sent up by him to speed up the recovery process.[67]

On September 8, the nation abandoned its policy of refusing foreign aid, citing a lack of resources due to the country's poor economy.[70] The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs gave an emergency grant of $50,000. UNICEF provided $116,000 worth of vitamins and medicine and an additional $116,950 in cash, as well as 28 t (31 short tons) of milk powder. They later provided vegetable seeds, dried fish, and garden fertilizer. The World Health Organization provided $7,000 worth of aid. Furthermore, the United Nations Development Programme awarded the country $30,000 in cash. The European Economic Community provided 330 short tons (300 t) of milk and $367,650 worth of cash.[68] In the middle of September, the United States approved $1 million in aid to the archipelago. Japan also sent a $500,000 check.[71] Australia awarded almost $500,000 worth of cash and food. New Zealand donated 22,680 kg (50,000 lb) of skimmed milk. The Norwegian Red Cross provided $58,500 in aid while the European Economic Community awarded just over $7,000 in cash. Belgium also provided three medical kits. The Swiss Red Cross awarded a little under $21,000 in cash. Germany provided slightly more than $50,000 in cash. France provided roughly $11,000 in donations to the nation's red cross. The Red Cross Society of China donated $20,000 in cash. Indonesia provided $25,000 worth of medicine. The United Kingdom granted $74,441 in aid. Overall, Relief Web reported that over $7.5 million was donated to the Philippines due to the storm.[68]

Starting on September 11, a massive relief item airlift was planned to assist the region.[72] Due to Tropical Storm June, 19 provinces had already been placed under a state of emergency. Following Ike, three other provinces were placed under a state of emergency.[72] Due to both Ike and June, 25 of the nation's 73 provinces were declared a disaster area.[42] Because of the destruction in the Philippines, the name Ike was retired and was replaced by Ian.[73] The name Nitang, was also retired, and was replaced by Ningning.[74]

See also

- Typhoon Mike – passed north of Mindanao and impacted the central Philippines, resulting in catastrophic damage

- Typhoon Nelson (1982) – resulted in significant flooding across the Philippines after slowly traversing the archipelago

- Typhoon Haiyan

- Typhoon Agnes (1984) – caused extensive damage and fatalities in the central Philippines before striking Vietnam

- Typhoon Rammasun

- Typhoon Rai – A Category 5 super typhoon that also ravaged through the Caraga, the Visayas and also Cebu in December 2021

Notes

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10-minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1-minute winds.[5]

- The death and missing columns includes deaths caused by Typhoon Fengshen (Frank), in the MV Princess of the Stars disaster.

- All Philippine currencies are converted to United States Dollars using Philippines Measuring worth with an exchange rate of the year 1984.

References

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1987). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1984 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1980–1989 (Report). Archived from the original (.TXT) on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Ike (1984239N08146). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Typhoon 13W Best Track (TXT) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. December 17, 2002. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Padua, Michael V. (November 6, 2008). PAGASA Tropical Cyclone Names 1963–1988 (TXT) (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- Hong Kong Observatory (1985). "Part III – Tropical Cyclone Summaries". Meteorological Results: 1984 (PDF). Meteorological Results (Report). Hong Kong Observatory. pp. 26–29. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "Typhoon unleashes rains on southern islands". United Press International. October 22, 1981 – via LexisNexis. (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Unleashes Rains On Southern Islands". Pharos-Tribune. Vol. 140, no. 208. United Press International. September 2, 1984. p. 24. Retrieved October 12, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Longshore, p. 185.

- "Typhoon Withers to Rainstorm in China". Associated Press. September 6, 1984.

- Philippine Storm Surge History. Project NOAH, University of the Philippines. November 23, 2013. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- Del Rosario, Eduardo D (August 9, 2011). Final Report on Typhoon "Yolanda" (Haiyan) (PDF) (Report). Philippine National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. pp. 77–148. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- Alojado, Dominic (2015). Worst typhoons of the Philippines (1947-2014) (PDF) (Report). Weather Philippines. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "10 Worst Typhoons that Went Down in Philippine History". M2Comms. August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- Lotilla, Raphael (November 20, 2013). "Flashback: 1897, Leyte and a strong typhoon". Rappler. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "Deadliest typhoons in the Philippines". ABS-CBNNews. November 8, 2013. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Padua, David M (June 10, 2011). "Tropical Cyclone Logs: Fengshen (Frank)". Typhoon 2000. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- Rabonza, Glenn J. (July 31, 2008). Situation Report No. 33 on the Effects of Typhoon "Frank"(Fengshen) (PDF) (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council (National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- "Typhoon Batters Philippines". Washington Post. September 4, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Typhoon death toll rises to 438, may go higher". United Press International. September 4, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Reed, Jack (September 2, 1984). "International News". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "International News". United Press International. September 6, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "International News". United Press International. September 4, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Alabastro, Ruben G. (September 5, 1984). "Philippines Death Toll Rises To 830; Typhoon Threatens Vietnam, China". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Scheweisburg, David R. (September 3, 1984). "Typhoon Ike leaves 325 dead in two days". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Rodriquez, Val (September 3, 1984). "International News". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Vicoy, Willy (September 5, 1984). "Typhoon death toll exceeds 660 in Philippines". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Foreign News Briefs". United Press International. September 3, 1984.

- Rodriguez, Val (September 3, 1984). "Typhoon Flattens Homes in Southern Philippines". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Reed, Jack (September 6, 1984). "Typhoon death toll tops 1,360 in Philippines". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Alabastro, Ruben G. (September 4, 1984). "International News". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Briscoe, David (September 6, 1984). "International News". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Katayama, Frederick H. (September 2, 1984). "International News". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Foreign News Briefs". United Press International. September 2, 1984.

- "Han River Floods Seoul". Ukiah Daily Journal. Vol. 124, no. 117. United Press International. September 3, 1984. p. 5. Retrieved October 12, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Floods kill 117 in South Korea". Galveston Daily News. Vol. 147, no. 142. Associated Press. September 3, 1984. p. 29. Retrieved October 12, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "International News". United Press International. September 3, 1984.

- "AROUND THE WORLD; 380 Die as a Typhoon Rakes the Philippines". New York Times. September 4, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- The Twelve Worst Typhoons of the Philippines (1947–2009) (Report). June 29, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "International News". United Press International. September 7, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "G. Structraul Measures" (PDF). The Study on the Nationwide Flood Risk Assessment and the Flood Mitigation Plan for the Selected Areas in the Republic of the Philippines (Report). CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Alabagastro, Ruben G. (September 4, 1984). "President Marcos Asks Nation To Unite, Help Save Lives After Natural Disaster". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Nitang's death toll totals 178 persons". The Bohol Chronicle. September 23, 1984. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- "Death toll is now 116 but may rise". The Bohol Chronicle. September 9, 1984. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- "Foreign News Briefs". United Press International. September 6, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Deadliest, most destructive cyclones of the Philippines". The Philippine Star. November 11, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 9, 2004. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- "Typhoon Ike hits China". United Press International. September 10, 1984.

- Gaw, Alex (September 7, 1984). "Typhoon Ike Runs Out Of Steam, Leaves Path Of Destruction". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Longshore, p. 186.

- "China cleans up after Typhoon Ike". United Press International. September 11, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Foreign News Briefs". United Press International. September 10, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Ike And Two Other Storms Killed 34, Injured 278". Associated Press. September 14, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "International News". United Press International. September 10, 1984.

- Disaster History: Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900–Present (PDF) (Report). Washington D.C., United States: United States Agency for International Development. August 1993. p. 49. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- "Typhoon Ike Hits China". St. Petersburg Times. United Press International. September 11, 1984. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- "Typhoon Heads For Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia". Associated Press. September 5, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. Typhoon 198411 (IKE) – Disaster Information. Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. AMeDAS IBARUMA (94001) @ Typhoon 198411. Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- "438 Killed by Typhoon Ike". Mohave Daily Miner. September 4, 1984. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- Alabastro, Ruben G. (September 5, 1984). "At least 476 die, thousands injured, in raging Philippines storm". Associated Press. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- "Police fire on demonstrators in Manila". The Globe and Mail. September 28, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "On This Day: September 3". British Broadcasting Company. September 3, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- "Marcos Ventures Into Rebel Area That Was Ravaged by Typhoon". Associated Press. September 9, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Philippines Typhoons Sep 1984 UNDRO Situation Reports 1 – 7 (Report). Relief Web. September 13, 1984. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "International News". Associated Press. September 10, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Reed, Jack (September 8, 1984). "International News". United Press International. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Foreign News Beliefs". United Press International. September 14, 1984. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Ike Batters Philippines". St. Petersburg Times. United Press International. September 4, 1984. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- Lei, Xiaotu; Zhou, Xiao; Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration) (February 2012). "Summary of Retired Typhoons in the Western North Pacific Ocean". Tropical Cyclone Research and Review. 1 (1): 23–32. Bibcode:2012TCRR....1...23L. doi:10.6057/2012TCRR01.03. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Cimatru, Frank (November 2, 2006). "Typhoon Naming". Pine for Pine. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

Further reading

- Longshore, David (2008). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones New Edition. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0-8160-7409-9.