Welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for citizens unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life.[1]

There is substantial variability in the form and trajectory of the welfare state across countries and regions.[2] All welfare states entail some degree of private–public partnerships wherein the administration and delivery of at least some welfare programs occur through private entities.[3] Welfare state services are also provided at varying territorial levels of government.[3]

Early features of the welfare state, such as public pensions and social insurance, developed from the 1880s onwards in industrializing Western countries.[4][2][5] World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II have been characterized as important events that ushered in the expansion of the welfare state.[4][6] The fullest forms of the welfare state were developed after World War II.[2]

Etymology

The German term sozialstaat ("social state") has been used since 1870 to describe state support programs devised by German sozialpolitiker ("social politicians") and implemented as part of Otto von Bismarck's conservative reforms.[7]

The literal English equivalent "social state" did not catch on in Anglophone countries.[8] However, during the Second World War, Anglican Archbishop William Temple, author of the book Christianity and the Social Order (1942), popularized the concept using the phrase "welfare state".[9] Bishop Temple's use of "welfare state" has been connected to Benjamin Disraeli's 1845 novel Sybil: or the Two Nations (in other words, the rich and the poor), where he writes "power has only one duty – to secure the social welfare of the PEOPLE".[10] At the time he wrote Sybil, Disraeli (later a prime minister) belonged to Young England, a conservative group of youthful Tories who disagreed with how the Whigs dealt with the conditions of the industrial poor. Members of Young England attempted to garner support among the privileged classes to assist the less fortunate and to recognize the dignity of labor that they imagined had characterized England during the Feudal Middle Ages.[11]

History

India

Emperor Ashoka of India put forward his idea of a welfare state in the 3rd century BCE. He envisioned his dharma (religion or path) as not just a collection of high-sounding phrases. He consciously tried to adopt it as a matter of state policy; he declared that "all men are my children"[12] and "whatever exertion I make, I strive only to discharge debt that I owe to all living creatures." It was a completely new ideal of kingship.[13] Ashoka renounced war and conquest by violence and forbade the killing of many animals.[14] Since he wanted to conquer the world through love and faith, he sent many missions to propagate Dharma. Such missions were sent to places like Egypt, Greece, and Sri Lanka. The propagation of Dharma included many measures of people's welfare. Centers of the treatment of men and beasts founded inside and outside of the empire. Shady groves, wells, orchards and rest houses were laid out.[15] Ashoka also prohibited useless sacrifices and certain forms of gatherings which led to waste, indiscipline and superstition.[14] To implement these policies he recruited a new cadre of officers called Dharmamahamattas. Part of this group's duties was to see that people of various sects were treated fairly. They were especially asked to look after the welfare of prisoners.[16][17]

However, the historical record of Ashoka's character is conflicted. Ashoka's own inscriptions state that he converted to Buddhism after waging a destructive war. However, the Sri Lankan tradition claims that he had already converted to Buddhism in the 4th year of his reign, prior to the conquest of Kalinga.[18] During this war, according to Ashoka's Major Rock Edict 13, his forces killed 100,000 men and animals and enslaved another 150,000. Some sources (particularly Buddhist oral legends) suggest that his conversion was dramatic and that he dedicated the rest of his life to the pursuit of peace and the common good.[19] However, these sources frequently contradict each other,[20] and sources soundly dated nearer to the Edicts (like Ashokavadana, circa 200 BCE at the earliest) describe Ashoka engaging in sectarian mass murder throughout his reign, and make no mention of the philanthropic efforts claimed by later legends. The interpretation of Ashoka's dharma after conversion is controversial, but in particular, the texts which describe him personally ordering the massacre of Buddhist heretics and Jains have been disputed by some fringe Buddhist scholars. They allege that these claims are propaganda, albeit without historical, archaeological, or linguistic evidence. It is unclear if they believe the entire Ashokavadana to be an ancient fabrication, or just the sections related to Ashoka's post-conversion violence.[21][22]

China

The Emperor Wen (203 – 157 BCE) of Han Dynasty instituted a variety of measures with resemblances to modern welfare policies. These included pensions, in the form of food and wine, to all over 80 years of age, as well as monetary support, in the form of loans or tax breaks, to widows, orphans, and elderly without children to support them. Emperor Wen was also known for a concern over wasteful spending of tax-payer money. Unlike other Han emperors, he wore simple silk garments. In order to make the state serve the common people better, cruel criminal punishments were lessened and the state bureaucracy was made more meritocratic. This led to officials being selected by examinations for the first time in Chinese history.[23][24]

Rome

The Roman Republic intervened sporadically to distribute free or subsidized grain to its population, through the program known as Cura Annonae. The city of Rome grew rapidly during the Roman Republic and Empire, reaching a population approaching one million in the second century AD. The population of the city grew beyond the capacity of the nearby rural areas to meet the food needs of the city.[25]

Regular grain distribution began in 123 BC with a grain law proposed by Gaius Gracchus and approved by the Roman Plebeian Council (popular assembly). The numbers of those receiving free or subsidized grain expanded to a high of an estimated 320,000 people at one point.[26][27] In the 3rd century AD, the dole of grain was replaced by bread, probably during the reign of Septimius Severus (193–211 AD). Severus also began providing olive oil to residents of Rome, and later the emperor Aurelian (270–275) ordered the distribution of wine and pork.[28] The doles of bread, olive oil, wine, and pork apparently continued until near the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD.[29] The dole in the early Roman Empire is estimated to account for 15 to 33 percent of the total grain imported and consumed in Rome.[30]

In addition to food, the Roman Republic also supplied free entertainment, through ludi (public games). Public money was allocated for the staging of ludi, but the presiding official increasingly came to augment the splendor of his games from personal funds as a form of public relations. The sponsor was able to cultivate the favor of the people of Rome.[31]

Arabia

The concept of states taxing for the welfare budget was introduced to the Arabs in the early 7th century by caliph Omar, most likely adapted from the newly Roman territories.[32] Zakat is also one of the five pillars of Islam and is a mandatory form of 2.5% income tax to be paid by all individuals earning above a basic threshold to provide for the needy once a year after Ramadan. Umar (584–644), leader of the Rashidun Caliphate (empire), established a welfare state through the Bayt al-mal (treasury), which for instance was used to stockpile food in every region of the Islamic Empire reserved for Arabs in the Peninsula.[33]

Modern

Otto von Bismarck established the first welfare state in a modern industrial society, with social-welfare legislation, in 1880s Imperial Germany.[34][35] Bismarck extended the privileges of the Junker social class to ordinary Germans.[34] His 17 November 1881 Imperial Message to the Reichstag used the term "practical Christianity" to describe his program.[36] German laws from this era also insured workers against industrial risks inherent in the workplace.[37]

In Switzerland, the Swiss Factory Act of 1877 limited working hours for everyone, and gave maternity benefits.[37] The Swiss welfare state also arose in the late 19th century; its existence and depth varied individually by canton. Some of the programs first adopted were emergency relief, elementary schools, and homes for the elderly and children.[38]

In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a version was set up by Count Eduard von Taaffe a few years after Bismarck in Germany. Legislation to help the working class in Austria emerged from Catholic conservatives. Von Taffe used Swiss and German models of social reform, including the Swiss Factory Act of 1877 German laws that insured workers against industrial risks inherent in the workplace to create the 1885 Trade Code Amendment.[37]

Changed attitudes in reaction to the worldwide Great Depression of the 1930s, which brought unemployment and misery to millions, were instrumental in the move to the welfare state in many countries. During the Great Depression, the welfare state was seen as a "middle way" between the extremes of communism on the left and unregulated laissez-faire capitalism on the right.[39] In the period following World War II, some countries in Western Europe moved from partial or selective provision of social services to relatively comprehensive "cradle-to-grave" coverage of the population. Other Western European states did not, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain and France.[40] Political scientist Eileen McDonagh has argued that a major determinant of where welfare states arose is whether or not a country had a historical monarchy with familial foundations (a trait that Max Weber called patrimonialism); in places where the monarchic state was viewed as a parental steward of the populace, it was easier to shift into a mindset where the industrial state could also serve as a parental steward of the populace.[41]

The activities of present-day welfare states extend to the provision of both cash welfare benefits (such as old-age pensions or unemployment benefits) and in-kind welfare services (such as health or childcare services). Through these provisions, welfare states can affect the distribution of wellbeing and personal autonomy among their citizens, as well as influencing how their citizens consume and how they spend their time.[42][43]

Analysis

Historian of the 20th-century fascist movement, Robert Paxton, observes that the provisions of the welfare state were enacted in the 19th century by religious conservatives to counteract appeals from trade unions and socialism.[44] Later, Paxton writes "All the modern twentieth-century European dictatorships of the right, both fascist and authoritarian, were welfare states… They all provided medical care, pensions, affordable housing, and mass transport as a matter of course, in order to maintain productivity, national unity, and social peace."[44] In Germany, Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party maintained the welfare state established by previous German governments, but restructured it so as to help only Aryan individuals considered worthy of assistance, excluding "alcoholics, tramps, homosexuals, prostitutes, the 'work-shy' or the 'asocial', habitual criminals, the hereditarily ill (a widely defined category) and members of races other than the Aryan."[45] Nevertheless, even with these limitations, over 17 million German citizens were receiving assistance under the auspices of the National Socialist People's Welfare by 1939.[45]

When social democratic parties abandoned Marxism after World War II, they increasingly accepted the welfare state as a political goal, either as a temporary goal within capitalism or an ultimate goal in itself.[44]

A theoretical addition from 2005 is that of Kahl in their article 'The religious roots of modern policy: Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed Protestant traditions compared'. They argue that the welfare state policies of several European countries can be traced back to their religious origins. This process has its origin in the 'poor relief' systems, and social norms present in Christian nations. The example countries are categorized as follows: Catholic – Spain, Italy and France; Lutheran – Denmark, Sweden and Germany; Reformed Protestant – Netherlands, the UK and the USA. The Catholic countries late adoption of welfare benefits and social assistance, the latter being splintered and meagre, is due to several religious and social factors. Alms giving was an important part of catholic society as the wealthy could resolve their sins through participation in the act. As such, begging was allowed and was subject to a greater degree of acceptance. Poverty was seen as being close to grace and there was no onus for change placed onto the poor. These factors coupled with the power of the church meant that state provided benefits did not arise until late in the 20th century. Additionally, social assistance was not done at a comprehensive level, each group in need had their assistance added incrementally. This accounts for the fragmented nature of social assistance in these countries.[46]

Lutheran states were early to provide welfare and late to provide social assistance but this was done uniformly. Poverty was seen as more of an individual affliction of laziness and immorality. Work was viewed as a calling. As such these societies banned begging and created workhouses to force the able-bodied to work. These uniform state actions paved the way for comprehensive welfare benefits, as those who worked deserved assistance when in need. When social assistance was delivered for those who had never worked, it was in the context of the uniform welfare provision. The concept of Predestination is key for understanding welfare assistance in Reformed Protestant states. Poor people were seen as being punished, therefore begging and state assistance was non existent. As such churches and charities filled the void resulting in early social assistance and late welfare benefits. The USA still has minimal welfare benefits today, because of their religious roots, according to Kahl.[46]

Also from 2005, Jacob Hacker stated that there was "broad agreement" in research on welfare that there had not been welfare state retrenchment. Instead, "social policy frameworks remain secure."[47]

Forms

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Broadly speaking, welfare states are either universal, with provisions that cover everybody; or selective, with provisions covering only those deemed most needy. In his 1990 book, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Danish sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen further identified three subtypes of welfare state models.[48]

Since the building of the decommodification index is limited[lower-alpha 1] and the typology is debatable, these 18 countries could be ranked from most purely social-democratic (Sweden) to the most liberal (the United States).[49]: 597 Ireland represents a near-hybrid model whereby two streams of unemployment benefit exist: contributory and means-tested. However, payments can begin immediately and are theoretically available to all Irish citizens even if they have never worked, provided they are habitually resident.[50]

Social stigma varies across the three conceptual welfare states. Particularly, it is highest in liberal states, and lowest in social democratic states.[51] Esping-Andersen proposes that the universalist nature of social democratic states eliminate the duality between beneficiaries and non-recipients, whereas in means-tested liberal states there is resentment towards redistribution efforts. That is to say, the lower the percent of GDP spent on welfare, the higher the stigma of the welfare state.[51] Esping-Andersen also argues that welfare states set the stage for post-industrial employment evolution in terms of employment growth, structure, and stratification. He uses Germany, Sweden, and the United States to provide examples of the differing results of each of the three welfare states.[51]

According to Evelyne Huber and John Stephens, different types of welfare states emerged as a result of prolonged government by different parties. They distinguish between social democratic welfare states, Christian democratic welfare states, and "wage earner" states.[52]

According to the Swedish political scientist Bo Rothstein, in non-universal welfare states, the state is primarily concerned with directing resources to "the people most in need". This requires tight bureaucratic control in order to determine who is eligible for assistance and who is not. Under universal models such as Sweden, on the other hand, the state distributes welfare to all people who fulfill easily established criteria (e.g. having children, receiving medical treatment, etc.) with as little bureaucratic interference as possible. This, however, requires higher taxation due to the scale of services provided. This model was constructed by the Scandinavian ministers Karl Kristian Steincke and Gustav Möller in the 1930s and is dominant in Scandinavia.[48]

Sociologist Lane Kenworthy argues that the Nordic experience demonstrates that the modern social democratic model can "promote economic security, expand opportunity, and ensure rising living standards for all ... while facilitating freedom, flexibility and market dynamism."[53]

American political scientist Benjamin Radcliff has also argued that the universality and generosity of the welfare state (i.e. the extent of decommodification) is the single most important societal-level structural factor affecting the quality of human life, based on the analysis of time serial data across both the industrial democracies and the American States. He maintains that the welfare state improves life for everyone, regardless of social class (as do similar institutions, such as pro-worker labor market regulations and strong labor unions).[54][lower-alpha 2]

The UBI as a replacement for the welfare state

The Universal Basic Income (UBI) has been proposed as a replacement for the traditional welfare state where social protection schemes are also social policies with a precise aim that can be regarded as social engineering. The focus of the UBI is granting individuals more freedom in determining life choices by providing a lifetime of financial security regardless of one's career preferences or lifepath.[55]

According to the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and nationally syndicated columnist Veronique de Rugy's statements made in 2016, as of 2014, the annual cost of a UBI in the US would have been about $200 billion cheaper than the current US system. By 2020, it would have been nearly a trillion dollars cheaper.[56]

By country or region

Australia

Prior to 1900 in Australia, charitable assistance from benevolent societies, sometimes with financial contributions from the authorities, was the primary means of relief for people not able to support themselves.[57] The 1890s economic depression and the rise of the trade unions and the Labor parties during this period led to a movement for welfare reform.[58]

In 1900, New South Wales and Victoria enacted legislation introducing non-contributory pensions for those aged 65 and over. Queensland legislated a similar system in 1907 before the Deakin government introduced a national aged pension under the Invalid and Old-Aged Pensions Act 1908. A national invalid disability pension was started in 1910, and a national maternity allowance was introduced by the Fisher government in 1912.[57][59]

In the 1920s and 1930s, detailed proposals were developed for a comprehensive national insurance scheme covering medical, disability, unemployment and pension benefits. Multiple royal commissions were held on the subject and the scheme was legislated as the National Health and Pensions Insurance Act 1938. However, the scheme was ultimately abandoned for cost reasons in the lead-up to the Second World War.[60]

During the Second World War, the federal government created a welfare state by enacting national schemes for: child endowment in 1941; a widows' pension in 1942; a wife's allowance in 1943; additional allowances for the children of pensioners in 1943; and unemployment, sickness, and special benefits in 1945.[57][59]

Medicare is Australia’s publicly-funded universal health care insurance scheme. Initially created in 1975 by the Whitlam Labor government under the name "Medibank". The Fraser Liberal government made significant changes to it from 1976 leading to its abolition in late 1981. The Hawke government reinstated universal health care in 1984 under the name "Medicare".

Canada

Canada's welfare programs[61] are funded and administered at all levels of government (with 13 different[61] provincial/territorial systems), and include health and medical care, public education (through graduate school), social housing and social services. Social support is given through programs including Social Assistance, Guaranteed Income Supplement, Child Tax Benefit, Old Age Security, Employment Insurance, Workers' Compensation, and the Canada/Quebec Pension Plans.[62]

France

After 1830, French liberalism and economic modernization were key goals. While liberalism was individualistic and laissez-faire in Britain and the United States, in France liberalism was based instead on a solidaristic conception of society, following the theme of the French Revolution, Liberté, égalité, fraternité ("liberty, equality, fraternity"). In the Third Republic, especially between 1895 and 1914 "Solidarité" ["solidarism"] was the guiding concept of a liberal social policy, whose chief champions were the prime ministers Leon Bourgeois (1895–96) and Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau (1899-1902).[63][64] The French welfare state expanded when it tried to follow some of Bismarck's policies.[65][66] Poor relief was the starting point.[67] More attention was paid to industrial labour in the 1930s during a short period of socialist political ascendency, with the Matignon Accords and the reforms of the Popular Front.[68] Paxton points out these reforms were paralleled and even exceeded by measures taken by the Vichy regime in the 1940s.

Germany

Some policies enacted to enhance social welfare in Germany were Health Insurance 1883, Accident Insurance 1884, Old Age Pensions 1889 and National Unemployment Insurance 1927. Otto von Bismarck, the powerful Chancellor of Germany (in office 1871–90), developed the first modern welfare state by building on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that had begun as early as in the 1840s. The measures that Bismarck introduced – old-age pensions, accident insurance, and employee health insurance – formed the basis of the modern European welfare state. His paternalistic programs aimed to forestall social unrest and to undercut the appeal of the new Social Democratic Party, and to secure the support of the working classes for the German Empire, as well as to reduce emigration to the United States, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist.[69][70][71] Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers through his high-tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.[72][73]

During the 12 years of rule by Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party, the welfare state established by previous German governments was maintained, but it was restructured so as to help only Aryan individuals considered worthy of assistance, excluding "alcoholics, tramps, homosexuals, prostitutes, the 'work-shy' or the 'asocial', habitual criminals, the hereditarily ill (a widely defined category) and members of races other than the Aryan."[45] Nevertheless, even with these limitations, over 17 million German citizens received assistance under the auspices of the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (NSV) by 1939.[45] The agency projected a powerful image of caring and support for those who were seen as full members of the German racial community, but it also inspired fear through its intrusive questioning and the threat of opening investigations on those who did not fulfill the criteria for support.[74]

India

The Directive Principles of State Policy, enshrined in Part IV of the Indian Constitution reflects that India is a welfare state. Food security to all Indians is guaranteed under the National Food Security Act, 2013 where the government provides food grains to people at a very subsidised rate.

As of 2020, the government's expenditure on social security and welfare (direct cash transfers, financial inclusion, health insurance, subsidies, rural employment guarantee), was approximately ₹1,400,000 crore (US$180 billion), which was 7.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).[75]

Latin America

Welfare states in Latin America have been considered as "welfare states in transition",[76] or "emerging welfare states".[77] Welfare states in Latin America have been described as "truncated": generous benefits for formal-sector workers, regressive subsidies and informal barriers for the poor to obtain benefits.[78] Mesa-Lago has classified the countries taking into account the historical experience of their welfare systems.[79] The pioneers were Uruguay, Chile and Argentina, as they started to develop the first welfare programs in the 1920s following a bismarckian model. Other countries such as Costa Rica developed a more universal welfare system (1960s–1970s) with social security programs based on the Beveridge model.[80] Researchers such as Martinez-Franzoni[81] and Barba-Solano[82] have examined and identified several welfare regime models based on the typology of Esping-Andersen. Other scholars such as Riesco[83] and Cruz-Martinez[84] have examined the welfare state development in the region.

About welfare states in Latin America, Alex Segura-Ubiergo wrote:

Latin American countries can be unequivocally divided into two groups depending on their 'welfare effort' levels. The first group, which for convenience we may call welfare states, includes Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and Brazil. Within this group, average social spending per capita in the 1973–2000 period was around $532, while as a percentage of GDP and as a share of the budget, social spending reached 51.6 and 12.6 percent, respectively. In addition, between approximately 50 and 75 percent of the population is covered by the public health and pension social security system. In contrast, the second group of countries, which we call non-welfare states, has welfare-effort indices that range from 37 to 88. Within this second group, social spending per capita averaged $96.6, while social spending as a percentage of GDP and as a percentage of the budget averaged 5.2 and 34.7 percent, respectively. In terms of the percentage of the population actually covered, the percentage of the active population covered under some social security scheme does not even reach 10 percent.[85]

Middle East

Saudi Arabia,[86][87][88] Kuwait,[89] and the United Arab Emirates[90] are examples of welfare states in the Middle East.

Nordic countries

The Nordic welfare model refers to the welfare policies of the Nordic countries, which also tie into their labor market policies. The Nordic model of welfare is distinguished from other types of welfare states by its emphasis on maximizing labor force participation, promoting gender equality, egalitarian and extensive benefit levels, the large magnitude of income redistribution and liberal use of the expansionary fiscal policy.[51]

While there are differences among the Nordic countries, they all share a broad commitment to social cohesion, a universal nature of welfare provision in order to safeguard individualism by providing protection for vulnerable individuals and groups in society and maximizing public participation in social decision-making. It is characterized by flexibility and openness to innovation in the provision of welfare. The Nordic welfare systems are mainly funded through taxation.[91]

People's Republic of China

China traditionally relied on the extended family to provide welfare services.[92] The one-child policy introduced in 1978 has made that unrealistic, and new models have emerged since the 1980s as China has rapidly become richer and more urban. Much discussion is underway regarding China's proposed path toward a welfare state.[93] Chinese policies have been incremental and fragmented in terms of social insurance, privatization, and targeting. In the cities, where the rapid economic development has centered, lines of cleavage have developed between state-sector and non-state-sector employees, and between labor-market insiders and outsiders.[94]

Sri Lanka

In 1995, the government started the Samurdhi (Prosperity) program aimed at reducing poverty, having replaced the Jana Saviya poverty alleviation programme that was in place at the time.[95]

Singapore

In Singapore, the government provides financial and social support through a variety of social assistance schemes for lower and middle-income Singaporeans. The Ministry of Social and Family Development runs ComCare, a program which provides income support for low-income citizen households through various schemes for short-to-medium term assistance, long-term assistance, child support, and urgent financial needs.[96] The Community Development Councils also run various local assistance schemes within their districts.[97] The Ministry of Manpower runs a Silver Support Scheme which provides additional financial support for low-income elderly with no family support.[98] Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health also runs MediFund to assist anyone on their behalf to pay off the rest of their medical bills after initial government subsidies, other health financing schemes as well as funds from the Central Provident Fund has been used.[99]

In 2012, the Community Health Assist Scheme (CHAS) was introduced. It is a medical card that provides extended subsidies exclusively for Singaporean citizens usually from lower-to-middle income households, as well as the older generations, where they could receive treatment for common illnesses, chronic health problems and specific dental issues at private clinics for free. The intentions behind the scheme were to encourage Singaporeans to use such a card and tap into the private healthcare sector for common or minor chronic illnesses, as well as dental care, to reduce the strain at public community hospitals. Originally, only a blue and orange card existed, depending on their household income.[100] The CHAS scheme was further expanded in 2019 to include a new green card that provides for all Singaporeans no matter their household income. As a result, all Singaporeans became covered for chronic and common illnesses as well as dentistry at privately owned clinics. Subsidies for complex chronic conditions was also increased.[100]

In addition, the National Council of Social Service coordinates a range of 450 non-government voluntary welfare organisations to provide social services, while raising funds through The Community Chest of Singapore.[101] Taking the World Bank's International Poverty Line (IPL)'s poverty threshold into account, the population of Singaporeans living below the poverty line is virtually non-existent.[102] Singapore also has one of the highest housing ownership rates in the world – over 90 percent – owing to the government's policy of constructing extensive and quality public housing throughout the country and providing extensive subsidies for its citizens to obtain them.[103]

United Kingdom

About the British welfare state, historian Derek Fraser wrote:

It germinated in the social thought of late Victorian liberalism, reached its infancy in the collectivism of the pre-and post-Great War statism, matured in the universalism of the 1940s and flowered in full bloom in the consensus and affluence of the 1950s and 1960s. By the 1970s it was in decline, like the faded rose of autumn. Both UK and US governments are pursuing in the 1980s monetarist policies inimical to welfare.[104]

The modern welfare state in the United Kingdom began operations with the Liberal welfare reforms of 1906–1914 under Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith.[105] These included the passing of the Old Age Pensions Act 1908, the introduction of free school meals in 1909, the Labour Exchanges Act 1909, the Development and Road Improvement Funds Act 1909, which heralded greater government intervention in economic development, and the National Insurance Act 1911 setting up a national insurance contribution for unemployment and health benefits from work.[106][107]

The People's Budget was introduced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, in 1909 to fund the welfare reforms. After much opposition, it was passed by the House of Lords on 29 April 1910.[108][109]

The minimum wage was introduced in the United Kingdom in 1909 for certain low-wage industries and expanded to numerous industries, including farm labour, by 1920. However, by the 1920s, a new perspective was offered by reformers to emphasize the usefulness of family allowance targeted at low-income families was the alternative to relieving poverty without distorting the labour market.[110][111] The trade unions and the Labour Party adopted this view. In 1945, family allowances were introduced; minimum wages faded from view. Talk resumed in the 1970s, but in the 1980s the Thatcher administration made it clear it would not accept a national minimum wage. Finally, with the return of Labour, the National Minimum Wage Act 1998 set a minimum of £3.60 per hour, with lower rates for younger workers. It largely affected workers in high turnover service industries such as fast-food restaurants, and members of ethnic minorities.[112]

December 1942 saw the publication of the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, commonly known as the Beveridge Report after its chairman, Sir William Beveridge. The Beveridge Report proposed a series of measures to aid those who were in need of help, or in poverty and recommended that the government find ways of tackling what the report called "the five giants": Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness. It urged the government to take steps to provide citizens with adequate income, adequate health care, adequate education, adequate housing, and adequate employment, proposing that "[a]ll people of working age should pay a weekly National Insurance contribution. In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed, retired, or widowed." The Beveridge Report assumed that the National Health Service would provide free health care to all citizens and that a Universal Child Benefit would give benefits to parents, encouraging people to have children by enabling them to feed and support a family.

The Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, and then the Labour Party all adopted the Beveridge Report's recommendations.[113] Following the Labour election victory in the 1945 general election many of Beveridge's reforms were implemented through a series of Acts of Parliament. On 5 July 1948, the National Insurance Act, National Assistance Act and National Health Service Act came into force, forming the key planks of the modern UK welfare state. In 1949, the Legal Aid and Advice Act was passed, providing the "fourth pillar"[114] of the modern welfare state, access to advice for legal redress for all.

Before 1939, most health care had to be paid for through non-government organisations – through a vast network of friendly societies, trade unions, and other insurance companies, which counted the vast majority of the UK working population as members. These organizations provided insurance for sickness, unemployment, and disability, providing an income to people when they were unable to work. As part of the reforms, the Church of England also closed down its voluntary relief networks and passed the ownership of thousands of church schools, hospitals and other bodies to the state.[115]

Welfare systems continued to develop over the following decades. By the end of the 20th-century parts of the welfare system had been restructured, with some provision channelled through non-governmental organizations which became important providers of social services.[116]

United States

The United States developed a limited welfare state in the 1930s.[117] The earliest and most comprehensive philosophical justification for the welfare state was produced by an American, the sociologist Lester Frank Ward (1841–1913), whom the historian Henry Steele Commager called "the father of the modern welfare state".

Ward saw social phenomena as amenable to human control. "It is only through the artificial control of natural phenomena that science is made to minister to human needs" he wrote, "and if social laws are really analogous to physical laws, there is no reason why social science should not receive practical application such as have been given to physical science."[118] Ward wrote:

The charge of paternalism is chiefly made by the class that enjoys the largest share of government protection. Those who denounce it are those who most frequently and successfully invoke it. Nothing is more obvious today than the single inability of capital and private enterprise to take care of themselves unaided by the state; and while they are incessantly denouncing "paternalism," by which they mean the claim of the defenseless laborer and artisan to a share in this lavish state protection, they are all the while besieging legislatures for relief from their own incompetency, and "pleading the baby act" through a trained body of lawyers and lobbyists. The dispensing of national pap to this class should rather be called "maternalism," to which a square, open, and dignified paternalism would be infinitely preferable.[119]

Ward's theories centred around his belief that a universal and comprehensive system of education was necessary if a democratic government was to function successfully. His writings profoundly influenced younger generations of progressive thinkers such as Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Dewey, and Frances Perkins (1880–1965), among others.[120]

The United States was the only industrialized country that went into the Great Depression of the 1930s with no social insurance policies in place. In 1935 Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal instituted significant social insurance policies. In 1938 Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, limiting the work week to 40 hours and banning child labor for children under 16, over stiff congressional opposition from the low-wage South.[117]

The Social Security law was very unpopular among many groups – especially farmers, who resented the additional taxes and feared they would never be made good. They lobbied hard for exclusion. Furthermore, the Treasury realized how difficult it would be to set up payroll deduction plans for farmers, for housekeepers who employed maids, and for non-profit groups; therefore, they were excluded. State employees were excluded for constitutional reasons (the federal government in the United States cannot tax state governments). Federal employees were also excluded.

By 2013, the U.S. remained the only major industrial state without a uniform national sickness program. American spending on health care (as a percent of GDP) is the highest in the world, but it is a complex mix of federal, state, philanthropic, employer and individual funding. The US spent 16% of its GDP on health care in 2008, compared to 11% in France in second place.[121]

Some scholars, such as Gerard Friedman, argue that labor-union weakness in the Southern United States undermined unionization and social reform throughout the United States as a whole, and is largely responsible for the anemic U.S. welfare state.[122] Sociologists Loïc Wacquant and John L. Campbell contend that since the rise of neoliberal ideology in the late 1970s and early 1980s, an expanding carceral state, or government system of mass incarceration, has largely supplanted the increasingly retrenched social welfare state, which has been justified by its proponents with the argument that the citizenry must take on personal responsibility.[123][124][125] Scholars assert that this transformation of the welfare state to a post-welfare punitive state, along with neoliberal structural adjustment policies and the globalization of the U.S. economy, have created more extreme forms of "destitute poverty" in the U.S. which must be contained and controlled by expanding the criminal justice system into every aspect of the lives of the poor.[126]

Other scholars such as Esping-Andersen argue that the welfare state in the United States has been characterized by private provision because such a state would better reflect the racial and sexual biases within the private sector. The disproportionate number of racial and sexual minorities in private sector jobs with weaker benefits, he argues, is evidence that the American welfare state is not necessarily intended to improve the economic situation of such groups.[51]

Effects

Effects of welfare on poverty

Empirical evidence suggests that taxes and transfers considerably reduce poverty in most Western countries whose welfare states constitute at least a fifth of GDP.[127][128]

| Country | Absolute poverty rate (1960–1991) (threshold set at 40% of U.S. median household income)[127] |

Relative poverty rate (1970–1997)[128] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | |

| 23.7 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 4.8 | |

| 9.2 | 1.7 | 12.4 | 4.0 | |

| 22.1 | 7.3 | 18.5 | 11.5 | |

| 11.9 | 3.7 | 12.4 | 3.1 | |

| 26.4 | 5.9 | 17.4 | 4.8 | |

| 15.2 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 5.1 | |

| 12.5 | 3.8 | 10.9 | 9.1 | |

| 22.5 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 11.9 | |

| 36.1 | 9.8 | 21.8 | 6.1 | |

| 26.8 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 4.1 | |

| 23.3 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 9.2 | |

| 16.8 | 8.7 | 16.4 | 8.2 | |

| 21.0 | 11.7 | 17.2 | 15.1 | |

| 30.7 | 14.3 | 19.7 | 9.1 | |

Effects of social expenditure on economic growth, public debt and education

Researchers have found very little correlation between economic performance and social expenditure.[129] They also see little evidence that social expenditures contribute to losses in productivity; economist Peter Lindert of the University of California, Davis attributes this to policy innovations such as the implementation of "pro-growth" tax policies in real-world welfare states,[130] nor have social expenses contributed significantly to public debt. Martin Eiermann wrote:

According to the OECD, social expenditures in its 34 member countries rose steadily between 1980 and 2007, but the increase in costs was almost completely offset by GDP growth. More money was spent on welfare because more money circulated in the economy and because government revenues increased. In 1980, the OECD averaged social expenditures equal to 16 percent of GDP. In 2007, just before the financial crisis kicked into full gear, they had risen to 19 percent – a manageable increase.[131]

A Norwegian study covering the period 1980 to 2003 found welfare state spending correlated negatively with student achievement.[132] However, many of the top-ranking OECD countries on the 2009 PISA tests are considered welfare states.[133]

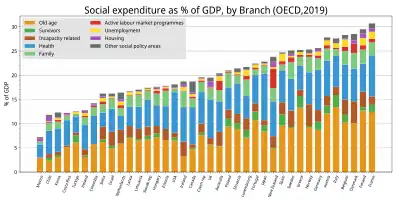

Social expenditure as a percentage of GDP

The table below shows social expenditure as a percentage of GDP for OECD member states in 2018:

| Nation | Social expenditure (% of GDP)[134] | Year[lower-alpha 3] |

|---|---|---|

| 31.0 | 2019 | |

| 28.9 | 2019 | |

| 29.1 | 2019 | |

| 28.3 | 2019 | |

| 28.2 | 2019 | |

| 26.9 | 2019 | |

| 25.5 | 2019 | |

| 25.9 | 2019 | |

| 25.3 | 2019 | |

| 24.0 | 2019 | |

| 24.0 | 2019 | |

| 22.6 | 2019 | |

| 21.6 | 2019 | |

| 22.3 | 2017 | |

| 21.1 | 2019 | |

| 21.3 | 2019 | |

| 20.6 | 2019 | |

| 18.1 | 2019 | |

| 19.4 | 2018 | |

| 19.2 | 2019 | |

| 18.7 | 2019 | |

| 17.7 | 2019 | |

| 16.7 | 2016 | |

| 18.0 | 2018 | |

| 16.1 | 2019 | |

| 16.4 | 2019 | |

| 16.7 | 2019 | |

| 16.3 | 2019 | |

| 16.7 | 2018 | |

| 17.4 | 2019 | |

| 13.4 | 2019 | |

| 12.0 | 2019 | |

| 12.2 | 2019 | |

| 11.4 | 2019 | |

| 7.5 | 2019 | |

| 12.2 | 2018 | |

| 13.1 | 2018 | |

| OCDE - Total | 20.0 | 2019 |

| 17.7 | 2019 |

Criticism and response

Early conservatives, under the influence of Thomas Malthus (1766-1834), opposed every form of social insurance "root and branch". Malthus believed that the poor needed to learn the hard way to practice frugality, self-control and chastity. Traditional conservatives also protested that the effect of social insurance would be to weaken private charity and loosen traditional social bonds of family, friends, religious and non-governmental welfare organisations.[135]

On the other hand, Karl Marx opposed piecemeal reforms advanced by middle-class reformers out of a sense of duty. In his Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League, written after the failed revolution of 1848, he warned that measures designed to increase wages, improve working conditions and provide social insurance were merely bribes that would temporarily make the situation of working classes tolerable to weaken the revolutionary consciousness that was needed to achieve a socialist economy.[lower-alpha 4] Nevertheless, Marx also proclaimed that the Communists had to support the bourgeoisie wherever it acted as a revolutionary progressive class because "bourgeois liberties had first to be conquered and then criticised".[137]

In the 20th century, opponents of the welfare state have expressed apprehension about the creation of a large, possibly self-interested, bureaucracy required to administer it and the tax burden on the wealthier citizens that this entailed.[138]

Conservative and libertarian groups such as The Heritage Foundation[139] and the Cato Institute[140] argue that welfare creates dependence, a disincentive to work and reduces the opportunity of individuals to manage their own lives.[141] This dependence is called a "culture of poverty", which is said to undermine people from finding meaningful work.[140] Many of these groups also point to the large budget used to maintain these programs and assert that it is wasteful.[139]

In the book Losing Ground, Charles Murray argues that welfare not only increases poverty, but also increases other problems such as single-parent households, and crime.[142]

In 2012, political historian Alan Ryan pointed out that the modern welfare state stops short of being an "advance in the direction of socialism. [...] [I]ts egalitarian elements are more minimal than either its defenders or its critics think". It does not entail advocacy for social ownership of industry. Ryan further wrote:

The modern welfare state, does not set out to make the poor richer and the rich poorer, which is a central element in socialism, but to help people to provide for themselves in sickness while they enjoy good health, to put money aside to cover unemployment while they are in work, and to have adults provide for the education of their own and other people's children, expecting those children's future taxes to pay in due course for the pensions of their parents' generation. These are devices for shifting income across different stages in life, not for shifting income across classes. Another distinct difference is that social insurance does not aim to transform work and working relations; employers and employees pay taxes at a level they would not have done in the nineteenth century, but owners are not expropriated, profits are not illegitimate, cooperativism does not replace hierarchical management.[143]

In 2017, historian Walter Scheidel argued that the establishment of welfare states in the West in the early 20th century could be partly a reaction by elites to the Bolshevik Revolution and its violence against the bourgeoisie, which feared violent revolution in its own backyard. They were diminished decades later as the perceived threat receded. Scheidel spoke to Vice's Matt Taylor in an interview:

It's a little tricky because the US never really had any strong leftist movement. But if you look at Europe, after 1917 people were really scared about communism in all the Western European countries. You have all these poor people, they might rise up and kill us and take our stuff. That wasn't just a fantasy because it was happening next door. And that, we can show, did trigger steps in the direction of having more welfare programs and a rudimentary safety net in response to fear of communism. Not that they [the communists] would invade, but that there would be homegrown movements of this sort. American populism is a little different because it's more detached from that. But it happens roughly at the same time, and people in America are worried about communism, too – not necessarily very reasonably. But that was always in the background. And people have only begun to study systematically to what extent the threat, real or imagined, of this type of radical regime really influenced policy changes in Western democracies. You don't necessarily even have to go out and kill rich people – if there was some plausible alternative out there, it would arguably have an impact on policy making at home. That's certainly there in the 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s. And there's a debate, right, because it becomes clear that the Soviet Union is really not in very good shape, and people don't really like to be there, and all these movements lost their appeal. That's a contributing factor, arguably, that the end of the Cold War coincides roughly with the time when inequality really starts going up again, because elites are much more relaxed about the possibility of credible alternatives or threats being out there.[144]

See also

- Constitutional economics

- Corporate welfare

- Economic security

- Flexicurity

- Free rider problem

- Happiness economics

- Hidden welfare state

- Involuntary unemployment

- Guaranteed minimum income

- Nanny state

- Social policy

- Social protection

- Social stratification

- State Socialism (Germany)

- Welfare capitalism

- Welfare economics

- Welfare reform

- Welfare state in the United Kingdom

- Models

- Transfer of wealth

- Housing

Notes

- According to the French sociologist Georges Menahem, Esping-Andersen's "decommodification index" aggregates both qualitative and quantitative variables for "sets of dimensions" which fluid, and pertain to three very different areas. These characters involve similar limits of the validity of the index and of its potential for replication. Cf. Menahem 2007.

- See also "this collection of full-text peer-reviewed scholarly articles on this subject" by Radcliff and colleagues (such as "Social Forces," "The Journal of Politics," and "Perspectives on Politics," among others)

- For social expenditure figures.

- "However, the democratic petty bourgeois want better wages and security for the workers, and hope to achieve this by an extension of state employment and by welfare measures; in short, they hope to bribe the workers with a more or less disguised form of alms and to break their revolutionary strength by temporarily rendering their situation tolerable."[136]

References

- "Welfare state". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- Béland, Daniel; Morgan, Kimberly J.; Obinger, Herbert; Pierson, Christopher (2021), Béland, Daniel; Leibfried, Stephan; Morgan, Kimberly J.; Obinger, Herbert (eds.), "Introduction", The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, Oxford University Press, pp. xxx–20, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198828389.013.1, ISBN 978-0-19-882838-9

- Béland, Daniel; Morgan, Kimberly J. (2021), Béland, Daniel; Leibfried, Stephan; Morgan, Kimberly J.; Obinger, Herbert (eds.), "Governance", The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, Oxford University Press, pp. 172–187, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198828389.013.10, ISBN 978-0-19-882838-9

- Skocpol, Theda (1992). Protecting Soldiers and Mothers. ISBN 9780674717664. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Koehler-Derrick, Gabriel; Lee, Melissa M. (2023). "War and Welfare in Colonial Algeria". International Organization. 77 (2): 263–293. doi:10.1017/S0020818322000376. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 256724058.

- O'Hara, Phillip Anthony, ed. (1999). "Welfare state". Encyclopedia of Political Economy. Routledge. p. 1247. ISBN 978-0-415-24187-8.

The welfare state emerged in the twentieth century as one institutional form of this socially protective response. In the 1930s, the responses of emerging welfare states to the Great Depression were to the immediate circumstances of massive unemployment, lost output, and collapse of the financial and trading systems. Planning was not a key element in the response to the crisis of capitalism. Instead the character of welfare state intervention can best be described as an 'interventionist drift', reflecting the spontaneous, uncoordinated reactions of the protective response...By the late 1970s, the welfare state and the capitalist economic structure in which it was placed were in a general state of crisis. There had never been a well articulated vision or ideological foundation of the welfare state.

- Fay, S. B. (January 1950). "Bismarck's Welfare State". Current History. XVIII (101): 1–7. doi:10.1525/curh.1950.18.101.1. S2CID 249690140.

- Smith, Munroe (December 1901). "Four German Jurists. IV". Political Science Quarterly. 16 (4): 641–679. doi:10.2307/2140421. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2140421.

- Gough, I. (1989), "The Welfare State", The New Palgrave Social Economics, New York: W.W. Norton, pp. 276–281

- Disraeli, Benjamin. "Chapter 14". Sybil. Vol. Book 4 – via Project Gutenberg.

- Alexander. Medievalism. pp. xxiv–xxv, 62, 93, and passim.

- The Edicts of King Asoka, Colostate.

- Thapar, Romila (2003). The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. UK: Penguin. p. 592. ISBN 9780-1-4193742-7. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Thakur, Upendra (1989). Studies in Indian History. Chaukhambha oriental research studies. Chaukhamba Orientalia. Retrieved 30 August 2013 – via The University of Virginia.

- Indian History, Tata McGraw-Hill Education, 1960, p. A-185, ISBN 978-0-07132923-1, retrieved 30 August 2013

- Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. 1960. pp. A–184–85. ISBN 9780071329231.

- Kher, N. N.; Aggarwal, Jaideep. A Text Book of Social Sciences. Pitambar Publishing. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-812091466-7 – via Google Books.

- Seneviratna, Anuradha (1994). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

- Thapar, Romila (1961). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press.

- Singh, Upinder (2012). "Governing the State and the Self: Political Philosophy and Practice in the Edicts of Aśoka". South Asian Studies. University of Delhi. 28 (2): 131–145. doi:10.1080/02666030.2012.725581. S2CID 143362618.

- Danver, Steven L. (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions [4 volumes]: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0.

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8.

- Montgomery, Laszlo. "Han Dynasty (Part 2)". chinahistorypodcast.libsyn.

- "Emperor Wendi of Western Han Dynasty". learnchinesehistory. 5 February 2013.

- Hanson, J. W.; Ortman, S. G.; Lobo, J. (2017). "Urbanism and the division of labour in the Roman Empire". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 14 (136): 20170367. doi:10.1098/rsif.2017.0367. PMC 5721147. PMID 29142013. p. 10.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2013). "The food supply of the capital". The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome. Cambridge University Press. pp. 262–277. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139025973.019. ISBN 978-1-13902597-3. pp. 262–264.

- Cristofori, Alessandro "Grain Distribution on Late Republican Rome," pp 146-151. , accessed 17 September 2018

- Erdkamp 2013, pp. 266–267.

- Linn, Jason (2012). "The Roman Grain Supply, 442–455". Journal of Late Antiquity. 5 (2): 298–321. doi:10.1353/jla.2012.0015. S2CID 161127852..

- Kessler, David; Temin, Peter (2007). "The Organization of the Grain Trade in the Early Roman Empire". The Economic History Review. 60 (2): 313–332. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2006.00360.x. JSTOR 4502066. S2CID 154086889. p. 316.

- Helen Lovatt, Status and Epic Games: Sport, Politics, and Poetics in the Thebaid ISBN 978-0-52184742-1 (Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 10

- Miaschi, John (25 April 2017). What Is A Welfare State? The World Atlas, accessed 24 October 2019.

- Crone, Patricia (2005). Medieval Islamic Political Thought. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 308–309. ISBN 0-7486-2194-6.

- Kersbergen, Kees van; Vis, Barbara (2013). Comparative Welfare State Politics: Development, Opportunities, and Reform. Cambridge UP. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-10765247-7.

- Wimmer, Andreas (13 February 2019). "Why Nationalism Works". Foreign Affairs: America and the World. ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Moritz Busch, Bismarck: Some secret pages from his history, Macmillan, New York (1898) Vol. II, p. 282

- Grandner, Margarete (1996). "Conservative Social Politics in Austria, 1880–1890". Austrian History Yearbook. 27: 77–107. doi:10.1017/S006723780000583X. S2CID 143805293.

- "Geschichte der Sozialen Sicherheit-Synthese" (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- O'Hara, Phillip Anthony, ed. (1999). "Welfare state". Encyclopedia of Political Economy. Routledge. p. 1245. ISBN 978-0-415-24187-8.

- Esping-Andersen 1990, p. 108.

- McDonagh, Eileen (December 2015). "Ripples from the First Wave: The Monarchical Origins of the Welfare State". Perspectives on Politics. 13 (4): 992–1016. doi:10.1017/S1537592715002273. S2CID 146441936.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1999). Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198742005.

- Rice, James Mahmud; Robert E. Goodin; Antti Parpo (September–December 2006). "The Temporal Welfare State: A Crossnational Comparison" (PDF). Journal of Public Policy. 26 (3): 195–228. doi:10.1017/S0143814X06000523. hdl:10419/31604. ISSN 0143-814X. S2CID 38187155. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2007.

- Paxton, Robert O. (25 April 2013). "Vichy Lives! – In a way". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 1933–1939, New York: The Penguin Press, 2005, p. 489

- Kahl, Sigrun (2005). The religious roots of modern poverty policy: Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed Protestant traditions compared. European Journal of Sociology, Vol. 46, No. 1, Religion and Society, pp. 91-126.

- Hacker, Jacob (2005). "Policy Drift: The Hidden Politics of US Welfare State Retrenchment". Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. Oxford University Press.

- Bo Rothstein, Just Institutions Matter: the Moral and Political Logic of the Universal Welfare State (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 18–27.

- Ferragina, Emanuele; Seeleib-Kaiser, Martin (2011). "Welfare regime debate: past, present, futures" (PDF). Policy & Politics. 39 (4): 583–611. doi:10.1332/030557311X603592. S2CID 146986126. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2020.

- Malnick, Edward (19 October 2013). "Benefits in Europe: country by country". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- Esping-Andersen 1990, p. 228

- Huber, Evelyne (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state : parties and policies in global markets. John D. Stephens. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-35646-9. OCLC 45276711.

- Kenworthy, Lane (2014). Social Democratic America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199322511 p. 9.

- Radcliff, Benjamin (2013). The Political Economy of Human Happiness. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ""Universal income is more than a new form of welfare state"". Polytechnique Insights. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- de Rugy, Veronique (7 June 2016). "Universal Basic Income's Growing Appeal". Mercatus Center. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- "History of Pensions and Other Benefits in Australia". Year Book Australia, 1988. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1988. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Garton, Stephen (2008). "Health and welfare". The Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Yeend, Peter (September 2000). "Welfare Review". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Gillespie, James (1991). The Price of Health: Australian Governments and Medical Politics 1910-1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–99. ISBN 9780521523226. OCLC 49638492.

- Chapter 1: What is Welfare? Archived 6 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 4 March 2019.

- Welfare State. Retrieved: 4 March 2019.

- Hayward, J. E. S. (1961). "The Official Social Philosophy of the French Third Republic: Léon Bourgeois and Solidarism". International Review of Social History. 6 (1): 19–48. doi:10.1017/S0020859000001759. JSTOR 44581447.

- Jack Hayward (2007). Fragmented France: Two Centuries of Disputed Identity. Oxford UP. p. 44. ISBN 9780199216314.

- Allan Mitchell, The Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870 (1991) online

- Nord, Philip (1994). "The Welfare State in France, 1870-1914". French Historical Studies. 18 (3): 821–838. doi:10.2307/286694. JSTOR 286694.

- Weiss, John H. (1983). "Origins of the French Welfare State: Poor Relief in the Third Republic, 1871-1914". French Historical Studies. 13 (1): 47–78. doi:10.2307/286593. JSTOR 286593.

- Dutton, Paul V. (2002). Origins of the French welfare state: The struggle for social reform in France, 1914–1947 (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2018 – via newbooks-services.de.

- E. P. Hennock, The Origin of the Welfare State in England and Germany, 1850–1914: Social Policies Compared (2007)

- Hermann Beck, Origins of the Authoritarian Welfare State in Prussia, 1815–1870 (1995)

- Streeck, Wolfgang; Thelen, Kathleen Ann (2005). Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-928046-9.

- Spencer, Elaine Glovka (1979). "Rulers of the Ruhr: Leadership and Authority in German Big Business before 1914". The Business History Review. 53 (1): 40–64. doi:10.2307/3114686. JSTOR 3114686. S2CID 154458964.

- Lambi, Ivo N. (1962). "The Protectionist Interests of the German Iron and Steel Industry, 1873-1879". The Journal of Economic History. 22 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1017/S0022050700102347. JSTOR 2114256. S2CID 154067344.

- Richard J. Evans (2005). The Third Reich in Power, 1933-1939. New York City, New York: The Penguin Press. p. 489-490.

- PIB (press release), IN: Government

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1996). Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economy. London: Sage Publications.

- Huber, Evelyne, & John D. Stephens (2012). Democracy and the Left. Social Policy and Inequality in Latin America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Holland, Alisha C. (2018). "Diminished Expectations: Redistributive Preferences in Truncated Welfare States". World Politics. 70 (4): 555–594. doi:10.1017/S0043887118000096. ISSN 0043-8871.

- Mesa-Lago, Carmelo (1994). Changing Social Security in Latin America. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Carlos Barba Solano, Gerardo Ordoñez Barba, and Enrique Valencia Lomelí (eds.), Más Allá de la pobreza: regímenes de bienestar en Europa, Asia y América. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte

- Franzoni, Juliana Martínez (2008). "Welfare Regimes in Latin America: Capturing Constellations of Markets, Families, and Policies". Latin American Politics and Society. 50 (2): 67–100. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2008.00013.x. S2CID 153771264.

- Barba Solano, Carlos (2005). Paradigmas y regímenes de bienestar. Costa Rica: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales

- Riesco, Manuel (2009). "Latin America: A new developmental welfare state model in the making?". International Journal of Social Welfare. 18: S22–S36. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2009.00643.x.

- Cruz-Martínez, Gibrán (2014). "Welfare State Development in Latin America and the Caribbean (1970s–2000s): Multidimensional Welfare Index, its Methodology and Results". Social Indicators Research. 119 (3): 1295–1317. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0549-7. S2CID 154720035.

- Segura-Ubiergo, Alex (2007). The Political Economy of the Welfare State in Latin America: Globalization, Democracy and Development. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 29–31

- "Saudi Arabia". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2000. 23 February 2001. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Social Services Archived 26 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Saudinf.

- "The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia - A Welfare State". mofa.gov.sa. Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, London: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Khalaf, Sulayman; Hammoud, Hassan (1987). "The Emergence of the Oil Welfare State". Dialectical Anthropology. 12 (3): 343–357. doi:10.1007/BF00252116. S2CID 153891759.

- Krane, Jim (15 September 2009). City of Gold: Dubai and the Dream of Capitalism. St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4299-1899-2.

- "About the Nordic welfare model". The Nordic Council. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Susanto, A. B.; Susanto, Patricia (2013). The Dragon Network: Inside Stories of the Most Successful Chinese Family Businesses. Wiley. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-11833938-1.

- Kennedy, Scott (2011). Beyond the Middle Kingdom: Comparative Perspectives on China's Capitalist Transformation. Stanford U.P. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-80477767-4.

- Huang, Xian (March 2013). "The Politics of Social Welfare Reform in Urban China: Social Welfare Preferences and Reform Policies". Journal of Chinese Political Science. 18 (1): 61–85. doi:10.1007/s11366-012-9227-x. S2CID 18306913.

- Irigoyen, Claudia. "The Samurdhi Programme in Sri Lanka". Centre for Public Impact. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "ComCare". msf.gov.sg. Ministry of Social and Family Development. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Getting help". cdc.org.sg. People's Association. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Silver Support Scheme". mom.gov.sg. Ministry of Manpower. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "MediFund". moh.gov.sg. Ministry of Health. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Liu, Vanessa (1 November 2019). "New Chas green card benefits, and enhanced subsidies for other Chas cards and Merdeka Generation start on Nov 1". www.straitstimes.com. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "Our Organisation". ncss.gov.sg. National Council of Social Service. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Household Income – Latest Data". singstat.gov.sg. Singapore Department of Statistics. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Majendie, Adam (8 July 2020). "Why Singapore Has One of the Highest Home Ownership Rates". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- Fraser, Derek (1984). The evolution of the British welfare state: a history of social policy since the Industrial Revolution (2nd ed.). p. 233.

- Castles, Francis G.; et al. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. Oxford Handbooks Online. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19957939-6 – via Google Books.

- Gilbert, Bentley Brinkerhoff (1976). "David Lloyd George: Land, the Budget, and Social Reform". The American Historical Review. 81 (5): 1058–1066. doi:10.2307/1852870. JSTOR 1852870.

- Derek Fraser 1973, The evolution of the British welfare state: a history of social policy since the Industrial Revolution.

- "1909 People's Budget". Liberal Democrat History Group. Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- Raymond, E. T. (1922). Mr. Lloyd George. George H. Doran co. p. 136.

April 29.

- Jane Lewis, "The English Movement for Family Allowances, 1917–1945". Histoire sociale/Social History 11.22 (1978) pp. 441–59.

- John Macnicol, Movement for Family Allowances, 1918–45: A Study in Social Policy Development (1980).

- Pat Thane2002, Cassell's Companion to Twentieth Century Britain pp. 267–68.

- Beveridge, Power and Influence

- Baksi, Catherine (1 August 2014). "Praise legal aid; don't bury it". The Law Society Gazette. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- "Bagehot: God in austerity Britain" The Economist, 10 December 2011

- Pawel Zaleski Global Non-governmental Administrative System: Geosociology of the Third Sector, [in:] Gawin, Dariusz & Glinski, Piotr [ed.]: "Civil Society in the Making", IFiS Publishers, Warszawa 2006

- Trattner, Walter I. (2007). From Poor Law to Welfare State: A History of Social Welfare in America (6th ed.). Free Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-41659318-8.

- Quoted in Thomas F. Gosset 1997, Race: The History of an Idea in America Oxford University Press, [1963], p. 161.

- Lester Frank Ward 1950, Forum XX, 1895, quoted in Henry Steel Commager's The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since the 1880s New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 210.

- Henry Steele Commager ed. 1967, Lester Ward and the Welfare State New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Mattke, Soeren; et al. (2011). Health and Well-Being in the Home: A Global Analysis of Needs, Expectations, and Priorities for Home Health Care Technology. Rand Corp. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-83305279-7.

- Friedman, Gerald (2000). "The Political Economy of Early Southern Unionism: Race, Politics, and Labor in the South, 1880-1953". The Journal of Economic History. 60 (2): 384–413. doi:10.1017/S0022050700025146. JSTOR 2566376. S2CID 154931829.

- John L. Campbell (2010). "Neoliberalism's penal and debtor states: A rejoinder to Loïc Wacquant". Theoretical Criminology. 14 (1): 68. doi:10.1177/1362480609352783. S2CID 145694058.

- Loïc Wacquant. Prisons of Poverty. University of Minnesota Press (2009). p. 55 ISBN 0816639019.

- Mora, Richard; Christianakis, Mary (January 2013). "Feeding the School-to-Prison Pipeline: The Convergence of Neoliberalism, Conservativism, and Penal Populism". Journal of Educational Controversy. 7 (1).

- Haymes, Stephen N.; de Haymes, María V.; Miller, Reuben J., eds. (2015). The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-41-567344-0.

- Kenworthy, Lane (1999). "Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–1139. doi:10.2307/3005973. JSTOR 3005973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2013.

- Moller, Stephanie; Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D.; Bradley, David; Nielsen, François (2003). "Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (1): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

- Atkinson, A. B. (1995). Incomes and the Welfare State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521557962.

- Lindert, Peter (2004). Growing Public: Social Spending And Economic Growth Since The Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521821759.

- Martin Eiermann, "The Myth of the Exploding Welfare State", The European, October 24, 2012.

- Falch, Torberg; Fischer, Justina AV (2008). "Does a generous welfare state crowd out student achievement? Panel data evidence from international student tests". Twi Research Paper Series.

- Shepherd, Jessica (7 December 2010). "World education rankings: which country does best at reading, maths and science?". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- "Social Expenditure - Aggregated data".

- Edwards, James Rolph (2007). "The Costs of Public Income Redistribution and Private Charity" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 21 (2): 3–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2008 – via mises.org.

- Marx, Karl (1850). Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League. Retrieved 5 January 2013 – via Marxists.org.

- Bernstein, Eduard (April 1897). "Karl Marx and Social Reform". Progressive Review (7).

- Ryan, Alan (2012). The Making of Modern Liberalism. Princeton and Oxford University Presses. pp. 26 and passim.

- Confronting the Unsustainable Growth of Welfare Entitlements: Principles of Reform and the Next Steps", The Heritage Foundation

- Niskanen, A. Welfare and the Culture of PovertyThe Cato Journal Vol. 16 No. 1

- Tanner, Michael (2008). "Welfare State". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 540–42. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n327. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Murray, Charles (1984). Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950–1980. Basic Books. pp. 58, 125, 115.

- Ryan, Alan (2012). On Politics, Book Two: A History of Political Thought From Hobbes to the Present. Liveright. pp. 904−905.

- Taylor, Matt (22 February 2017). "One Recipe for a More Equal World: Mass Death". Vice. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

Further reading

- Arts, Wil; Gelissen, John (2002). "Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report". Journal of European Social Policy. 12 (2): 137–158. doi:10.1177/0952872002012002114. S2CID 154811175.

- Bartholomew, James (2015). The Welfare of Nations. Biteback. p. 448. ISBN 978-1849548304.

- Francis G. Castles; et al. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. Oxford Handbooks Online. p. 67. ISBN 9780199579396.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta; Politics against markets, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1985).

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0069028573.

- Kenworthy, Lane. Social Democratic America. Oxford University Press (2014). ISBN 0199322511

- Korpi, Walter; "The Democratic Class Struggle"; London: Routledge (1983).

- Koehler, Gabriele and Deepta Chopra; "Development and Welfare Policy in South Asia"; London: Routledge (2014).

- Kuhnle, Stein (2000). "The Scandinavian welfare state in the 1990s: Challenged but viable". West European Politics. 23 (2): 209–228. doi:10.1080/01402380008425373. S2CID 153443503.

- Kuhnle, Stein. Survival of the European Welfare State 2000 Routledge ISBN 041521291X

- Menahem, Georges (2007). "The decommodified security ratio: A tool for assessing European social protection systems" (PDF). International Social Security Review. 60 (4): 69–103. doi:10.1111/j.1468-246X.2007.00281.x. S2CID 64361693. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2018.

- Pierson, P. (1994). Dismantling the Welfare State?: Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pierson, Paul (1996). "The New Politics of the Welfare State" (PDF). World Politics. 48 (2): 143–179. doi:10.1353/wp.1996.0004. JSTOR 25053959. S2CID 55860810. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2017.

- Rothstein, Bo. Just institutions matter: the moral and political logic of the universal welfare state (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

- Radcliff, Benjamin (2013) The Political Economy of Human Happiness (New York: Cambridge University Press).

- Reeves, Rachel; McIvor, Martin (2014). "Clement Attlee and the foundations of the British welfare state". Renewal. 22 (3–4): 42–59. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Tanner, Michael (2008). "Welfare State". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 540–542. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n327. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Van Kersbergen, K. "Social Capitalism"; London: Routledge (1995).

- Vrooman, J Cok (2012). "Regimes and cultures of social security: Comparing institutional models through nonlinear PCA". International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 53 (5–6): 444–477. doi:10.1177/0020715212469512. S2CID 154903810.

- [https://mimesisjournals.com/ojs/index.php/tcrs/article/view/277 Silvestri P., "The All too Human Welfare State. Freedom Between Gift and Corruption", Teoria e critica della regolazione sociale, 2/2019, pp. 123–145. doi:10.7413/19705476007

External links

Data and statistics

- OECD

- Contains information on social security developments in various EC member states from 1957 to 1978

- Contains information on social security developments in various EC member states from 1979 to 1989

- Contains information on social assistance programmes in various EC member states in 1993

- Contains detailed information on the welfare systems in the former Yugoslav republics

- The impact of benefit and tax uprating on incomes and poverty (UK)

| Library resources about Welfare state |