Tell es-Sultan

Tell es-Sultan (Arabic: تل السلطان, lit. Sultan's Hill), also known as Tel Jericho (Hebrew: תל יריחו) or Ancient Jericho, is an archaeological site and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the State of Palestine, in the city of Jericho, consisting of the remains of the oldest fortified city in the world.[1][2]

Tell es-Sultan | |

Shown within State of Palestine | |

| Location | Jericho, West Bank, Palestine |

|---|---|

| Region | Levant |

| Coordinates | 31°52′16″N 35°26′38″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 10,000 BCE |

| Abandoned | c. 900 BCE |

| Cultures | Natufian (Epipaleolithic), Jericho IX (Pottery Neolithic), Canaanite (Bronze Age) |

| Official name | Ancient Jericho/Tell es-Sultan |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 2023 |

| Reference no. | 1687 |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

It is located adjacent to the Ein as-Sultan refugee camp, two kilometres north of the centre of the Palestinian city of Jericho. The tell was inhabited from the 10th millennium BCE, what makes Jericho a contestant to the title of oldest continually inhabited city on earth.[3] The site is notable for its role in the history of Levantine archaeology.

The area was first identified as the site of ancient Jericho in modern times by Charles Warren in 1868, on the basis of its proximity to the large spring of Ein es-Sultan, that had been proposed as the spring of Elisha by Edward Robinson three decades earlier.

History

Natufian hunter-gatherers, c. 10,000 BCE

The first permanent settlement on the site developed between 10,000 and 9000 BCE.[4][5] During the Younger Dryas period of cold and drought, permanent habitation of any one location was impossible. However, Tell es-Sultan was a popular camping ground for Natufian hunter-gatherer groups due to the nearby Ein as-Sultan spring; these hunter-gatherers left a scattering of crescent-shaped microlith tools behind them.[6] Around 9600 BCE the droughts and cold of the Younger Dryas stadial came to an end, making it possible for Natufian groups to extend the duration of their stay, eventually leading to year-round habitation and permanent settlement. Epipaleolithic construction at the site appears to predate the invention of agriculture, with the construction of Natufian structures beginning earlier than 9000 BCE, the very beginning of the Holocene epoch in geologic history.[7]

Pre-Pottery Neolithic, c. 8500 BCE

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A phase at Tell es-Sultan (c. 8500–7500 BCE)[8] saw the emergence of one of the world's first major proto-cities. As the world warmed up, a new culture based on agriculture and sedentary dwelling emerged, which archaeologists have termed "Pre-Pottery Neolithic A" (abbreviated as PPNA), sometimes called the Sultanian era after the town. PPNA villages are characterized by small circular dwellings, burial of the dead under the floor of buildings, reliance on hunting wild game, the cultivation of wild or domestic cereals, and no use of pottery yet.

The PPNA-era town, a settlement of around 40,000 square metres (430,000 sq ft), contained round mud-brick houses, yet no street planning.[9] Circular dwellings were built of clay and straw bricks left to dry in the sun, which were plastered together with a mud mortar. Each house measured about 5 metres (16 ft) across, and was roofed with mud-smeared brush. Hearths were located within and outside the homes.[10]

The identity and number of the inhabitants of Jericho during the PPNA period is still under debate, with estimates going as high as 2000–3000, and as low as 200–300.[11][12] It is known that this population had cultivated emmer wheat, barley and pulses and hunted wild animals.

The town was surrounded by a massive stone wall over 3.6 metres (12 ft) high and 1.8 metres (6 ft) wide at the base (see Wall of Jericho), inside of which stood a stone tower (see Tower of Jericho), placed in the centre of the west side of the tell.[13] This tower was the tallest structure in the world until the Pyramid of Djoser, and the second-oldest tower after the one at Tell Qaramel.[14][15] The wall and tower were built around 8000 BCE.[16][17] For the tower carbon dates published in 1981 and 1983 indicate that it was built around 8300 BCE and stayed in use until c. 7800 BCE.[13] The wall and tower would have taken a hundred men more than a hundred days to construct,[12] thus suggesting some kind of social organization and division of labour.

The major structures highlight the importance of the Tell for the understanding of settlement patterns in the Sultanian period in the southern Levant.[18]

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB)

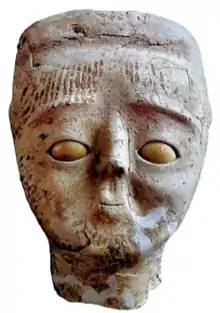

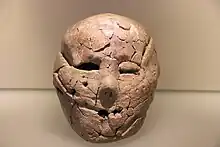

After a few centuries, the first settlement was abandoned. After the PPNA settlement phase there was a settlement hiatus of several centuries, then the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B settlement was founded on the eroded surface of the tell. This second settlement, established in 6800 BCE, perhaps represents the work of an invading people who absorbed the original inhabitants into their dominant culture. Artifacts dating from this period include ten plastered human skulls, painted so as to reconstitute the individuals' features.[19] These represent either teraphim or an early example of portraiture in art history, and it is thought that they were kept in people's homes while the bodies were buried.[7][20]

The architecture consisted of rectilinear buildings made of mudbricks on stone foundations. The mudbricks were loaf-shaped with deep thumb prints to facilitate bonding. No building has been excavated in its entirety. Normally, several rooms cluster around a central courtyard. There is one big room (6.5 m × 4 m (21 ft × 13 ft)) and a second slightly smaller room (7 m × 3 m (23 ft × 10 ft)) containing internal divisions. The remaining areas are small, and presumably used for storage. The rooms have red or pinkish terrazzo-floors made of lime. Some impressions of mats made of reeds or rushes have been preserved. The courtyards have clay floors.

Kathleen Kenyon interpreted one building as a shrine. It contained a niche in the wall. A chipped pillar of volcanic stone that was found nearby might have fit into this niche.

The dead were buried under the floors or in the rubble fill of abandoned buildings. There are several collective burials. Not all the skeletons are completely articulated, which may point to a time of exposure before burial. A skull cache contained seven skulls. The jaws were removed and the faces covered with plaster; cowries were used as eyes. A total of ten skulls were found. Modelled skulls were found in Tell Ramad and Beisamoun as well.

Other finds included flints, such as arrowheads (tanged or side-notched), finely denticulated sickle-blades, burins, scrapers, a few tranchet axes, obsidian, and green obsidian from an unknown source. There were also querns, hammerstones, and a few ground-stone axes made of greenstone. Other items discovered included dishes and bowls carved from soft limestone, spindle whorls made of stone and possible loom weights, spatulae and drills, stylised anthropomorphic plaster figures, almost life-size, anthropomorphic and theriomorphic clay figurines, as well as shell and malachite beads.

Bronze Age

A succession of settlements followed from 4500 BCE onward, the largest constructed in 2600 BCE.[19]

Tell es-Sultan was continually occupied into the Middle Bronze Age; it was destroyed in the Late Bronze, after which it no longer served as an urban centre. The city was surrounded by extensive defensive walls strengthened with rectangular towers, and possessed an extensive cemetery with vertical shaft-tombs and underground burial chambers; the elaborate funeral offerings in some of these may reflect the emergence of local kings.[21]

During the Middle Bronze Age Tell es-Sultan was a small prominent city of the Canaan region, reaching its greatest Bronze Age extent in the period from 1700 to 1550 BCE. It seems to have reflected the greater urbanization in the area at that time, and has been linked to the rise of the Maryannu, a class of chariot-using aristocrats linked to the rise of the Mitannite state to the north. Kathleen Kenyon reported "the Middle Bronze Age is perhaps the most prosperous in the whole history of Kna'an. ... The defenses ... belong to a fairly advanced date in that period" and there was "a massive stone revetment ... part of a complex system" of defenses (pp. 213–218).[22] The Bronze-Age city fell in the 16th century at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, the calibrated carbon remains from its City-IV destruction layer dating to 1617–1530 BCE. Notably this carbon dating c. 1573 BCE seemingly confirmed the accuracy of the stratigraphical dating c. 1550 by Kenyon. However, The current Italian-Palestinian excavation team, directed by Lorenzo Nigro, tested two samples from the final destruction of the city in 2000; one sample dated to 1347 BC (+/- 85 years) and the other dated to 1597 (+/- 91 years). The earlier date would be consistent with the Biblical account. [23]

Iron Age

Tell es-Sultan remained unoccupied from the end of the 15th to the 10th–9th centuries BCE, when the city was rebuilt.[24] Of this new city not much more remains than a four-room house on the eastern slope.[25] By the 7th century Jericho had become an extensive town, but this settlement was destroyed in the Babylonian conquest of Judah in the early 6th century.[24]

Abandonment of the tell

After the destruction of the Judahite city by the Babylonians in the late 6th century,[24] whatever was rebuilt in the Persian period as part of the Restoration after the Babylonian captivity, left only very few remains.[25] The tell was abandoned as a place of settlement not long after this period.[25]

Archaeological excavation

.jpg.webp)

The first excavations of the tells around Ain es Sultan (Arabic: عين سلطان, lit. 'Sultan's spring') were made by Charles Warren in 1868 on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Warren excavated nine mounds in the area of the spring; during one of the excavations his workmen dug through the mud bricks of the wall without realizing what it was.[26]

The spring had been identified in 1838 in Edward Robinson's Biblical Researches in Palestine as "the scene of Elisha's miracle", on the basis of it being the primary spring near to Jericho.[27] On this basis Warren proposed the surrounding mounds as the site of Ancient Jericho, but he did not have the funds to carry out a full excavation. Believing that it was clearly the spring where Elisha healed, he suggested shifting the entire mound for evidence, which he thought could be done for £400.[28]

Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger excavated Tell es-Sultan and Tulul Abu el-'Alayiq between 1907 and 1909 and in 1911, finding the remains of two walls which they initially suggested supported the biblical account of the Battle of Jericho. They later revised this conclusion and dated their finds to the Middle Bronze Age (1950–1550 BCE).[29]

The site was again excavated by John Garstang between 1930 and 1936, who again raised the suggestion that remains of the upper wall was that described in the Bible, and dated to around 1400 BCE.[30]

Extensive investigations using more modern techniques were made by Kathleen Kenyon between 1952 and 1958. Her excavations discovered a tower and wall in trench I. Kenyon provided evidence that both constructions dated much earlier than previous estimates of the site's age, to the Neolithic, and were part of an early proto-city. Her excavations found a series of seventeen early Bronze Age walls, some of which she thought may have been destroyed by earthquakes. The last of the walls was put together in a hurry, indicating that the settlement had been destroyed by nomadic invaders. Another wall was built by a more sophisticated culture in the Middle Bronze Age with a steep plastered escarpment leading up to mud bricks on top.[30][31]

Lorenzo Nigro and Nicolo Marchetti conducted excavations in 1997–2000. Since 2009 the Italian-Palestinian archaeological project of excavation and restoration was resumed by Rome "La Sapienza" University and Palestinian MOTA-DACH under the direction of Lorenzo Nigro and Hamdan Taha.[32]

Renewed excavations were carried out at Tell es-Sultan from 2009 to 2023 by the Italian-Palestinian Expedition directed by Lorenzo Nigro for Sapienza University of Rome and Jehad Yasine for the Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities of Palestine. These works uncovered several monuments of the Bronze Age City: the Palaces on the Spring Hill (Early Bronze II–III, 3000–2350 BCE; MB I–II, called "Palace of the Shepherds Kings" and the MB III palace, called "Hyksos' Palace"), the south-east Gate, called Jerusalem Gate, and several traits of the ancient city walls.[33]

Walls

The PPNA-era city wall was designed for either defensive or flood protection purposes;[12] the mass of the wall (approximately 1.5 to 2 metres (4.9 to 6.6 ft)[34] thick and 3.7 to 5.2 metres (12 to 17 ft) high) as well as that of the tower suggests a defensive purpose as well. It is suggested to date to approximately 8000 BCE.[17] If interpreted as an "urban fortification", the Wall of Jericho is the oldest city wall discovered by archaeologists anywhere in the world.[35] Surrounding the wall was a ditch 8.2 metres (27 ft) wide by 2.7 metres (9 ft) deep, cut through solid bedrock with a circumference around the town of as much as 600 metres (2,000 ft).[36] Kenyon commented that the "labour involved in excavating this ditch out of solid rock must have been tremendous."[22]

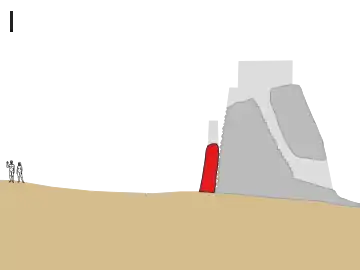

Phase I: A 3.6 m high stone perimeter wall was constructed, abutting the outer face of the tower. The two human figures on the left show the approximate scale.

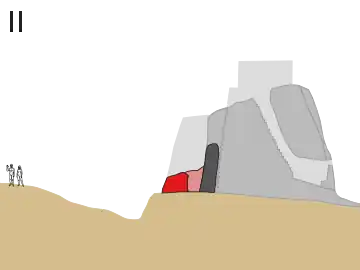

Phase I: A 3.6 m high stone perimeter wall was constructed, abutting the outer face of the tower. The two human figures on the left show the approximate scale. Phase II: An additional wall and outer ditch were added. The space between the two walls was filled with debris from the ditch. A 'skin wall' was built to reinforce the tower, incorporating part of the first wall.

Phase II: An additional wall and outer ditch were added. The space between the two walls was filled with debris from the ditch. A 'skin wall' was built to reinforce the tower, incorporating part of the first wall. Phase III: As the ditch silted up, a new wall was built on top of the remains of the two earlier ones. At the same time, the lower entrance to the tower was blocked.

Phase III: As the ditch silted up, a new wall was built on top of the remains of the two earlier ones. At the same time, the lower entrance to the tower was blocked.

Tower of Jericho

The Tower of Jericho is an 8.5-metre-tall (28 ft) stone structure, built in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period around 8000 BCE.[16] It is among the earliest stone monuments of mankind.[39] Conical in shape, the tower is almost 9 metres (30 ft) in diameter at the base, decreasing to 7 metres (23 ft) at the top, with walls approximately 1.5 metres (5 ft) thick. It contains an internal staircase with 22 stone steps.[19][6] The construction of the tower is estimated to have taken 11,000 working days.

Comparative chronology

References

- "Photos: Jericho's Tell es-Sultan added to UNESCO World Heritage list". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Ancient Jericho/Tell es-Sultan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- Agencies, The New Arab Staff & (September 18, 2023). "UN committee lists W.Bank's Jericho as a World Heritage Site". The new Arab.

- "Ancient Jericho: Tell es-Sultan". UNESCO. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Prehistoric Cultures". Museum of Ancient and Modern Art. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Mithen, Steven (2006). After the ice: a global human history, 20,000-5000 BCE (1st Harvard University Press pbk. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-674-01999-7.

- Freedman et al., 2000, p. 689–671.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (2014). "The Archaeology of Collapse and Resilience: Tell es-Sultan/ancient Jericho as a Case Study". Rome "la Sapienza" Studies on the Archaeology of Palestine & Transjordan. 11: 272. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Old Testament Jericho". OurFatherLutheran.net. 20 February 2008. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- Mithen (2006), p. 54

- Kenyon, Kathleen Mary (February 15, 2023). "Jericho". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- Akkermans, Peter M. M; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2004). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BCE). Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Barkai, Ran; Liran, Roy (November 2008). "Midsummer Sunset at Neolithic Jericho". Time and Mind. 1 (3): 273–284 [279]. doi:10.2752/175169708X329345. S2CID 161987206. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Ślązak, Anna (21 June 2007). "Yet another sensational discovery by Polish archaeologists in Syria". Science in Poland service, Polish Press Agency. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Mazurowski, R.F. (2007). "Pre- and Protohistory in the Near East: Tell Qaramel (Syria)". Newsletter 2006. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, Warsaw University. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- O'Sullivan, Arieh (14 February 2011). "'World's first skyscraper sought to intimidate masses'". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- Kenyon, Kathleen M.; Holland, Thomas A. (1960). Excavations at Jericho: The architecture and stratigraphy of the Tell: plates. Vol. 3. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-9500542-3-0. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Cremin, Aedeen (2007). Archaeologica: The World's Most Significant Sites and Cultural Treasures. Frances Lincoln. pp. 209ff. ISBN 978-0-7112-2822-1.

- Ring, Trudy; K. A. Berney; R. M. Salkin; N. Watson; S. La Boda; P. Schellinger, eds. (1994). Jericho (West Bank). pp. 367–370. ISBN 978-1-884964-05-3. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Janson, H. W.; Janson, Anthony F. (2004). History of Art: The Western Tradition. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall Professional. ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Kuijt 2012, p. 167.

- Kenyon, Kathleen Mary (1957). Digging up Jericho: the results of the Jericho excavations, 1952–1956. Praeger. p. 68. ISBN 9780758162519. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- http://www.lasapienzatojericho.it/Biblioteca/Jericho/JERICHO_AND_THE_CHRONOLOGY_OF_PALESTINE.pdf

- Jacobs 2000, p. 691.

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon, eds. (2001). Jericho. pp. 256–260. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) (Snippet view). - Wagemakers, Bart (2014). Archaeology in the 'Land of Tells and Ruins': A History of Excavations in the Holy Land Inspired by the Photographs and Accounts of Leo Boer. Oxbow Books. p. 122ff. ISBN 978-1-78297-246-4.

- Edward Robinson; Eli Smith (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine. Crocker & Brewster. pp. 283ff.

- Warren, Charles (1876). Underground Jerusalem. Richard Bentley & Son. p. 196.

- Hoppe, Leslie J. (September 2005). New light from old stories: the Hebrew scriptures for today's world. Paulist Press. pp. 82ff. ISBN 978-0-8091-4116-6. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (13 February 1995). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Vol. A–D. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 275ff. ISBN 978-0-8028-3781-3. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Davis, Miriam C. (2008). Dame Kathleen Kenyon: digging up the Holy Land. Left Coast Press. pp. 101ff. ISBN 978-1-59874-326-5. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Tell es-Sultan/Jericho". Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Tell-es Sultan". lasapienzatojericho.it. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- William A. Haviland; Harald E. L. Prins; Dana Walrath; Bunny McBride (30 March 2007). Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge. Cengage Learning. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Ancient Jericho: Tell es-Sultan. 2012 application for nomination as a World Heritage Site, in UNESCO's "Tentative Lists"

- Negev & Gibson, eds. (2001), Fortifications: Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, p. 180

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1986). "The Walls of Jericho: An Alternative Interpretation". Current Anthropology. 27 (2): 157–162. doi:10.1086/203413. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 7798010.

- Kenyon, Kathleen M. (1981). Excavations at Jericho, Vol. III: The Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Tell. London: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. ISBN 0-9500542-3-2.

- Wynne Parry (February 18, 2011). "Tower of Power: Mystery of Ancient Jericho Monument Revealed". livescience.com.

Bibliography

- Jacobs, Paul F. (2000). "Jericho". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-9053565032.

- Kuijt, Ian (2012). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oup USA. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5.

External links

Media related to Tell es-Sultan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tell es-Sultan at Wikimedia Commons