Teraphim

Teraphim (singular is unattested, plural: Hebrew: תְּרָפִים tərāfīm) is a Hebrew word from the Bible, found only in the plural, of uncertain etymology.[1] Despite being plural, Teraphim may refer to singular objects, using the Hebrew plural of excellence.[2] The word Teraphim is explained in classical rabbinical literature as meaning disgraceful things[3] (dismissed by modern etymologists), and in many English translations of the Bible it is translated as idols, or household god(s) although its exact meaning is more specific than this, but unknown precisely.

Teraphim in the Hebrew Bible

Rachel

According to Genesis 31, Rachel takes the teraphim belonging to her father Laban when her husband Jacob escapes. She hides them on a camel's saddle and sits on them when Laban comes looking for them, and claims that she cannot get up because she is "in the women's way". From this it can be deduced that they were small, perhaps 30–35 cm (12–14 in).[4] Her motive in doing so is subject to difference. Some argue she took the teraphim in order for her father not to have idolatrous paraphernalia, while others claim that she wanted to use them herself. Others say it was at the direction of her husband Jacob.[5] Others point to the use of teraphim for divination in other Biblical passages, and argue that Rachel either wanted to prevent Laban from divining their location as they fled, or wanted to perform divination of her own.[6] Rachel may also have intended to assert her independence from Laban and her legal rights within the extended family, as in ancient Middle Eastern custom the possession of familial idols was a marker of authority and property rights within a family.[7]

Michal

In 1 Samuel 19, Michal helps her husband David escape from her father Saul. She lets him out through a window, and then tricks Saul's men into thinking that a teraphim in her bed is actually David. This suggests the size and shape is that of a man.[8] It also refers to "the" teraphim, which implies that there was a place for teraphim in every household. Van der Toorn claims that "there is no hint of indignation at the presence of teraphim in David's house."[9] However, the same word is used in 1 Samuel 15:23 where Samuel rebukes Saul and tells him that "presumption is as iniquity and teraphim". Here the idea is that rebellion is just as bad as teraphim, the use of which is thus denounced as idolatry. Others explain that the teraphim in this context refer to decorative statues, not to idolatrous ritual items.[10]

Other passages

Teraphim are mentioned in Hosea 3:4, where it says that "the Israelites will live many days without king or prince, without sacrifice or sacred stones, without ephod or teraphim." As in the narrative of Micah's Idol the teraphim is closely associated with the ephod, and both are mentioned elsewhere in connection with divination;[1] it is thus a possibility that the Teraphim were involved with the process of cleromancy. The teraphim were outlawed in Josiah's reform (2 Kings 23:24).

In the Book of Zechariah (Zechariah 10:2) it states: "For the teraphim utter nonsense, and the diviners see lies; the dreamers tell false dreams, and give empty consolation. Therefore the people wander like sheep; they are afflicted for want of a shepherd."

In the Book of Ezekiel 21:21, Nebuchadrezzar uses divination to determine which rebel to attack first: belomancy (i.e., casting of arrows inscribed with names of projected victims); necromancy (teraphim were religious images sometimes expected to convey messages to the living [see Zech 10.2]); and hepatoscopy (making predictions based on the configurations and markings of animal livers).

In post-biblical writing

Josephus mentions that there was a custom of carrying housegods on journeys to foreign lands,[11] and it is thus possible that the use of teraphim continued in popular culture well into the Hellenistic period and possibly beyond.[3]

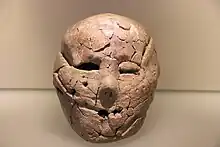

According to Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, Teraphim were made from the heads of slaughtered first-born male adult humans. The heads were shaved, salted, spiced, with a golden plate placed under the tongue, and magic words engraved upon the plate. It was believed that the Teraphim, mounted on the wall, would talk to people.[3] Similar explanations are cited in the writings of Eleazar of Worms and Tobiah ben Eliezer.[12]

During the excavation of Jericho by Kathleen Kenyon, evidence of the use of plastered human skulls as cult objects was uncovered, lending credence to the rabbinical conjecture.[13] The implied size and the fact that Michal could pretend that one was David, has led to the rabbinical conjecture that they were heads, possibly mummified human heads.[1]

Suggested meaning and use

Casper Labuschagne claims that it comes via cacophemic metathesis from the root פתר, "to interpret".[14] Karel Van der Toorn argues that they were ancestor figurines rather than household deities, and that the "current interpretation of the teraphim as household deities suffers from a onesided use of Mesopotamian material."[15]

That Micah used the Teraphim as an idol, and that Laban regarded the Teraphim as representing "his gods", is thought to indicate that they were evidently images of deities.[3] It is considered possible that they originated as a fetish, possibly initially representative of ancestors, but gradually becoming oracular.[3]

Benno Landsberger and later Harry Hoffner derive the word from Hittite tarpiš, "the evil daemon".[16]

Shiki-y-Michaels[17], in one element of an ambitious presentation, recaps some scholars' guesses. Speiser: resh‐pei‐he, to “to be limp”, also “to sink, relax”. Albright has it from resh‐pei‐yud, with the sense of “slacken or sag”. Pope argues “tremble” as in resh‐pei‐pei. Labuschagne agreed with forebears who said the term Teraphim was related to Hebrew "rophe," and that Teraphim were healers. "Almost every characteristic that commentators have given to the teraphim, (oracles, healers, gods) they have attributed to the rephaim... who are deified ancestors in" various Semitic languages.[17] Reducing two mysteries to one question, this solution is neat to the point of demanding caution.

Notes

- Smith, William Robertson; Box, George Herbert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 637.

- Van Der Toorn, 206.

- Jewish Encyclopedia, Teraphim

- Van Der Toorn, 205.

- Reuven Chaim Klein (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1946351463.

- Rachel's Stealing of the Terafim: Exegetical Approaches

- Pritchard, James B., ed. Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament with supplement. Princeton University Press, 2016. p220; M. Greenberg, "Another Look at Rachel's Theft of the Teraphim", JBL 81:3 (1962): 239-248.

- BDB, p. 1076.

- Van Der Toorn, 216.

- Reuven Chaim Klein (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-1946351463.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, volume 18, 9:5

- Reuven Chaim Klein (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. p. 361. ISBN 978-1946351463.

- Peake's commentary on the Bible

- Casper Labuschagne, "Teraphim : a new proposal for its etymology," Vetus Testamentum 16 [1966] 116.

- Van Der Toorn, 222.

- Hoffner, Jr; Hoffner, Harry A. (1968). "Hittite Tarpis and Hebrew Teraphim". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 27 (1): 61. doi:10.1086/371931. S2CID 163796930.

- Michaels 2015.

References

- Karel Van Der Toorn, "The Nature of the Biblical Teraphim in the Light of Cuneiform Evidence," CBQ 52 (1990), 203–222.

- Michaels, Sheila (2015-04-30). "Rachel Steals Teraphim, Inanna Steals Mes. Transfer of Divine Authority: Harran to Bethlehem, Eridu to Uruk". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-22.